Margaret Mead – Tales From The Jungle

Exploring the work of Margaret Mead, this film investigates the 12 months Mead spent with the Samoans in the Twenties.

Her resulting book, Coming Of Age In Samoa, had a huge impact on Western culture.

Mead believed cultures like the Samoans could teach people how to live in harmony. Her book depicts a society of free love — devoid of jealousy and teenage turmoil.

But, decades later, her work was criticised as being tainted by her romantic views and strong belief in liberal values.

Tales From The Jungle examines whether Mead’s study was merely misinterpretation and romantic wishful thinking.

See also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derek_Freeman

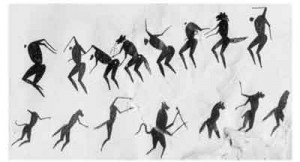

Rock Art Research in South Africa

Therianthropes and trance dance from artwork painted by Kalahari artist, the late Vetkat Regopstaan Kruiper (with permission)

Ethno-archaeology: Oral narratives and rock art

The focus of my research is on the method of recording oral narratives and their link to, and possible use in, the interpretation of rock art, specifically rock engravings. Research on indigenous knowledge and artefacts falls within a contentious area of indigenous archaeology associated with colonialists’ geographic and intellectual imperialism. It is necessary for my contextual approach to include, as in the exploration of myths, the theoretical setting of ethno-archaeology within which my research takes place. In the discipline of archaeology the use of ethnography falls under what Renfrew and Bahn (1991: 339) call ‘What did they think?’ The use of ‘they’ points not only to ethical issues of ‘othering’, the negative artificial construction of two camps of cultures and the corresponding approaches of scholars and present day descendants of the artists, but also to the time gap between the artists of the past and the present (Lewis-Williams & Pearce, 2004).

The rock paintings situated in caves, shelters and on portable stones, mostly in the mountainous regions in South Africa, and rock engravings situated predominantly in the plateau areas, on boulders on hills or near rivers, date mostly from within the last few thousand years. However, small mobiliary painted stones from Apollo 11 Cave and an engraved ochre piece from Blombos Cave date from some 25 000 and up to 70 000 years ago respectively (Lewis-Williams & Pearce, 2004). This considerable antiquity complicates any attempts at interpreting the rock art by way of oral narratives, even those recorded by the earliest colonialists. Furthermore, our views and therefore theories on art, oral narrative and methodology are constantly changing (Bahn, 1998).

Lévi-Strauss – A Propos Tristes Tropiques

P.S. This is intended for non-profit commentary and educational purposes. No copyright infringement intended. Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use.

An Introduction To Three Nambikwara Ethnohistories

January, 2019: Edwin B. Reesink – Allegories of Wildness – Three Nambikwara ethnohistories of sociocultural and linguistic change and continuity – Rozenberg Publishers – ISBN 978 90 3610 173 8 – 2010 – will be online soon.

International fame for the Nambikwara came from the central role they play in the work of the late Claude Lévi-Strauss. In his most popular book, Tristes Tropiques, over fifty years ago, he already had painted a particular picture of the Nambikwara way of life. Until the end of his long life this great scholar reminisced about his formative years in anthropology and the influence of the several Indian peoples he encountered during his travels in the interior of Brazil. In effect, the Nambikwara, as seen in the quote, occupy a special place, one not just of scientific interest but particularly one of a sympathy and feeling sometimes not readily associated with this anthropologist. At the time of the travels by Lévi-Strauss and the other people of his expedition, the dry season of 1938, the Nambikwara happened to be in an intermediate phase of their history: enjoying their political autonomy yet already shaped and devastated by the encroachment of Brazilian society.

The sparse, intermediate but regular contacts with Brazilians made them susceptible to being devastated yet further by epidemics. Previously, from 1907 onward, the Brazilians by means of the so-called Rondon Mission penetrated into the vast territories in which lived a large number of different local groups who each considered themselves to be different from their neighbours. Rondon, the State and later researchers recognized this diversity but ultimately still tended to maintain the idea of “one Nambikwara people”. Rondon’s purpose was to build a telegraph line to the Madeira River and hence to connect Amazonia with the rest of the country while, concomitantly, preparing to take possession of an enormous territory inhabited by a number of independent peoples. Rondon and some of his people succeeded in establishing a pacific relation with a number of local peoples of the Nambikwara ensemble: mainly those of the Parecis Plateau and north of Vilhena (in what is now Rondônia).

*

All I can say to you is that the few months I spent among the Nambikwara may have been those I retain the best memories of, among all of the contacts I had with other populations in Brazil. (…) there has been no Indian population I have known that has attracted so much and with whom I felt so close.

(Lévi-Strauss; from interviews with Marcelo Fiorini, end of 2004 and beginning of 2005, published in Ethnies nr. 33-34, pp. 108-9; my translation).

*

The building of the Telegraph Line and the establishment of stations and agricultural activities to support the annual expeditions and the posterior sustenance of the people manning the telegraph posts, already meant a significant penetration into their lands. The best known Nambikwarist, the late David Price, estimated the overall territory of all local peoples at this time to have been some 500.000 square kilometers, something like the size of France. One might say that the actual land taken in the beginning represented a very small amount of this total. However, the peaceful relations established with a few villages already implied that contagion of unknown diseases would necessarily follow. The very fact that Rondon represented the Republic – that is so-called “national sovereignty” – when he penetrated these lands and simply took possession of what he needed is also highly significant. The Line was a line of colonialist penetration initiating the expropriation of natural resources and potential genocide which such a venture always engendered. Rondon knew he was entering the homelands of another people and, being uninvited, felt violent reactions against him and his subordinates were justified. Hence he was determined not to retaliate and to find ways of establishing and maintaining friendly relations. Yet there was never any doubt that the Republic came first and was entitled to take factual possession of what “already belonged” to it. On the other hand, Indians were people, and precisely because of that human condition could be elevated to higher levels of “civilization”, even to be “citizens”: if the Republic subtracted territory from “its Indians” then it should take care of them by “civilizing” these people and, for example, by “educating” such “semi-nomads” so they could henceforth live comfortably in the very much smaller area that was to be magnanimously granted to them by the State. At the end of his life Rondon is said to have regretted his actions as they did not produce the beneficial effects he expected. If so, he was right in the end. The official State policy of civilizing did neither work in the expected way nor offer real benevolent protection against the greed of colonialist expansion and expropriation of territory, tremendous riches and wealth by Brazilian society. Nor against genocidal practices, sometimes even promoted – camouflaged but real – by the State itself. Only very recently in history the legal protection became more efficient, recognized ampler territorial rights and expanded to include cultural and linguistic rights. Needless to say that Brazilian society in general still holds on to evolutionary and ethnocentric views that demote Indian peoples to either innocent or brutal savages. And, even today, for what seems to be the great majority, these abstract “Indians” are granted far too many rights when they are held to be standing in the way of “progress”. Read more

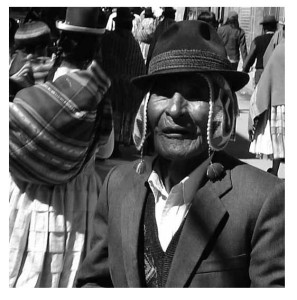

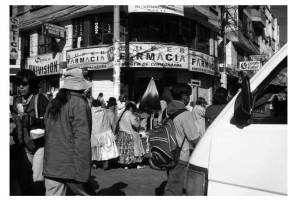

Van yatiri tot privékliniek – Interculturaliteit in de gezondheidszorg in Bolivia – deel 1

Toegang tot goede gezondheidszorg is een belangrijke basisbehoefte. Maar wat is goede gezondheidszorg? Als wij in Nederland ziek worden, hebben we er in de meeste gevallen wel vertrouwen in dat onze huisarts of een specialist in het ziekenhuis ons weer geneest. We begrijpen min of meer hoe het zorgsysteem in elkaar steekt, en hoeven ons over de kosten van de behandeling nauwelijks zorgen te maken omdat we verzekerd zijn. Als we in het buitenland zijn, wordt de situatie al lastiger. De arts spreekt onze taal niet en we weten niet hoe het systeem werkt. Hetzelfde geldt natuurlijk voor immigranten in Nederland die het Nederlands nog niet goed beheersen.

Dit soort problemen speelt ook in andere landen met een cultureel diverse bevolking. Voor de inheemse inwoners van ontwikkelingslanden kan het Westerse zorgsysteem vreemd, onbegrijpelijk en angstaanjagend overkomen. In veel gevallen vertrouwen zij liever op hun eigen inheemse geneeskunde, vaak uitgevoerd door medicijnmannen en -vrouwen. Read more

Van yatiri tot privékliniek – Interculturaliteit in de gezondheidszorg in Bolivia – deel 2

4. El Alto: Capital Andina

Net als dat Bolivia een bijzonder land is, is El Alto een bijzondere stad in Bolivia. Oorspronkelijk is El Alto ontstaan als een sloppenwijk van La Paz. La Paz ligt in een dal naast de hoogvlakte. Toen het dal van La Paz vol raakte, is de stad letterlijk ‘over de rand’ gekropen, de hoogvlakte op.

Van sloppenwijk tot miljoenenstad

De bevolkingsgroei in deze sloppenwijk nam een vlucht na de Nationale Revolutie van 1952. De hierin afgedwongen landhervormingen zorgden ervoor dat kleine boeren niet langer konden overleven van de landbouw (Kranenburg 2002). Deze voornamelijk inheemse (Aymara) boeren hoopten op een beter leven in de stad en kwamen in El Alto terecht, wat ook weer andere migranten van Aymara afkomst aantrok. Zij voelden zich het meest thuis in deze stad waar ook hun eigen inheemse en plattelandstradities behouden bleven (Muriel Hernandez 1995). Nadat in de jaren ’80 veel mijnen sloten, trokken ook de voornamelijk Quechua mijnwerkers naar El Alto (Kranenburg 2002). In 1985 werd de wijk een onafhankelijke gemeente. Bijna alle inwoners van El Alto (alteños) komen van de hoogvlakte, en dan niet alleen uit Bolivia maar zelfs een deel uit Peru. Ook voor deze inheemse Peruanen is de culturele overgang van hun dorp naar El Alto kleiner dan naar bijvoorbeeld de Peruaanse hoofdstad Lima. Migranten uit andere delen van Bolivia zijn er eigenlijk nauwelijks, al neemt de laatste jaren het aantal migranten uit La Paz toe. Zij ontvluchten de dure woningmarkt van La Paz. Inmiddels wonen er naar schatting tegen de één miljoen mensen in El Alto. Hiermee is het de grootste stad op de hoogvlakte en ze wordt dan ook wel ‘Capital Andina’ genoemd (van Rijn 2006).

Ondanks dat in Bolivia stedelijke gebieden gemiddeld rijker zijn dan het platteland, leeft tweederde van de inwoners van El Alto onder de armoedegrens. Nog eens 17% leeft in extreme armoede. Dit is lager dan het nationale gemiddelde. Basisbehoeften zoals sanitaire voorzieningen, onderwijs en toegang tot zorg worden niet vervuld (INE 2005). Veel huizen, vooral in de nieuwere wijken aan de rand van de stad, hebben nog geen goede sanitaire voorzieningen, al wordt hier wel aan gewerkt door de gemeente (van Rijn 2006). Read more