Reshaping Remembrance ~ The Eating Afrikaner: Notes For A Concise Typology

… eating is one of the principal forms of commerce between ourselves and the world, and one of the principal factors in constituting our relations with other people.[i]

… eating is one of the principal forms of commerce between ourselves and the world, and one of the principal factors in constituting our relations with other people.[i]

On the glamorous and the mundane

Of course the mouth is the entrance to an exit, about which, as Dean Swift would tell you, one might also be concerned; but for the moment we can sit on that subject, leaving the phenomenology of its outbreathings to make the reputation of some Sehr Gelehrter Prof. Dr. Krapphauser, or Swami Poepananda. Om![ii]

Versfeld’s joke resonates with Wilma Stockenström’s somewhat grim image of a human being: ‘behaarde buis van glorie en smet’ [hairy tube of glory and smut].[iii] At one end of the tube, one could say, a human being ingests less or more elaborately prepared earthly sustenance, as the everyday patty or as paté de foie gras, in a ritualised or ceremonial manner, only to return it to the earth at the other end in a humbler form and mostly in an unceremonious fashion. Indeed, it is a trajectory ‘van glans én van vergetelheid’ [of the glamorous and the mundane].[iv]

This thought alone should be sufficient to put into perspective the quest for an original and essential Afrikaner kitchen. Curiously enough, this line of thinking is pursued to absurd lengths in current fascistoid confabulations about Afrikaner ethnic identity: the ‘smut’ and the ‘glory’, the abject and the heroic, are regarded as elements comprising a self-sustaining feedback loop of ethnic preparedness. The violence of colonialism, the road-kill of history, so to speak, should not be rejected or forgotten by the Afrikaner volk, but ritualistically embraced and imbibed in order to build up strength for what is envisaged as a renewed struggle for self-preservation, under a perceived threat of future ethnic violence.

Inasmuch as these bizarre fantasies are motivated by self-preservation, they constitute, paradoxically, an example of a general weakness in the Afrikaner culture, including the food culture. This debilitating weakness is the result of a misconception of what might command attention and respect: only the glorious struggle and shining surface of nationalist preparedness. In perceptions of this nature the ‘smut’ aspect is fully subsumed under the ‘glory’ aspect. The humble, the abject is not valued in its own right, but only embraced if it can serve a higher, more heroic purpose.

The gist of my speculations in this essay is that it is precisely the inflated attention and respect for the ‘glamour’ and for the moment of permanence, a narcissistic moment, which undermines the Afrikaner culinary tradition from the inside. To illustrate this, I wish to present for consideration a number of notions and practices within specific sections of the Afrikaner community; consideration not by just anyone, but particularly by the purgative and imaginative spirit of the late Martin Versfeld. It was he, who, in his wise, humorous and mischievious essays, presented his calvinistic fellow-Afrikaners with a sensual ethic of eating and cooking, an ethic where the splendour and the simplicity, the glamorous and the mundane of eating and cooking are poetically intertwined. Moreover, it is an ethic which contains both the permanence and the transcendence, of the kitchen and of the table, within a horizon of attention and respect. One could object that Versfeld lights up this whole horizon with the glory of god. Nonetheless, my answer would be that the glory of the kind of god Versfeld believes in seems to me a far more appealing option than the glory of an ethnically exclusive tribe. One reason for this appeal, is that he can easily recognize his god in the gods of other cultures and enrich and modulate his faith with wisdom from a variety of sources.[v]

The big eat

We can never be festive if we wish each day to be a feast. Where everything is festive nothing is festive. … It is gluttonous, perhaps deadly to want that every day.[vi]

In the daily round of contemporary consumer madness it is precisely the rhythm of festivity and everyday domesticity, of indulgence and staple that is corrupted. This corruption is fostered by the images of bedecked tables and plated food presented in popular lifestyle magazines. The culinary festive and glamorous occasion is celebrated ad nauseum. Should one contend that the contemporary Afrikaner’s way with food has to a great extent become absorbed by the extravagant consumer culture, then one could claim that this could only have happened because, apart from a tradition of domestic simplicity, modesty, even frugality, another tradition, one of over-indulgence and lavish ostentation, is also associated with the Afrikaner culinary tradition. Moreover, this tradition has been an important instrument of social ranking ever since the early days of the Cape Colony. Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ The Windpump

1.

1.

Elbie Immelman[i] tells the story of Piet Olivier and his treacherous windpump in the South African newspaper Die Burger of 9 September 2000. His family had been farming on the Karoo farm Kweekwa in the vicinity of Victoria-West since 1853. Because the farm of 29 000 morgen (about 60 000 acres) was situated on the route between Victoria-West, Pampoenpoort, Carnarvon, Williston and Calvinia, it served as a point of call for the British patrols who had to feed their horses and take in fresh water supplies. Piet’s wife, Chrissie, managed to turn these stopovers to account, however. Whenever she saw dust rising from the transport road, she started to bake bread with the flour she kept hidden in an old well near their house.

When windpumps were introduced into South Africa, Piet Olivier was one of the two farmers in the Victoria-West district who acquired one. He was quite prosperous – he had 204 horses, which the British all commandeered, down to the last cart and saddle horse. To demonstrate their benevolence they allowed him to keep all of four donkeys for his own use, of course with the stipulation that he was not to tend to them or stable them.

But that was not the end of the British soldiers’ generous treatment of the farmer. One day the British raised the dust on the transport road to serve a summons on Oom Piet. The charge: spying. He had been sending secret messages with a heliograph. Although he was taken aback (he did not own a heliograph), he was not going to take this lying down. When a deputation of the Mounted Troopers arrived to escort him to town, he put his foot down and refused to go with these South Africans who had joined the British forces. The British and none but the British were to escort him. The Troopers returned to town tail between the legs, and delivered Oom Piet’s message to the Sixth Inniskillin Dragoons, who had been stationed on the edge of the mountain to the south of Victoria-West since the Northern Cape farmers had rebelled.

Eleven Dragoons duly set off to Kweekwa and ordered Oom Piet to walk to the town. It being beneath his dignity to walk for 40 km while the hated British soldiers were on horseback, Oom Piet once again refused: the Troopers had to organise transport for him. They had not reckoned with Oom Piet’s obstinacy, of course, and so they had to stay the night on the farm, Tant Chrissie having to serve them. The second day on the farm came and went, and on the third day an obdurate Oom Piet suggested they fetch his foreman Hugh Wilson’s cart from Witkranz. If two Troopers were to put their horses before the cart, they could ride in it to town, together with Oom Piet… What the tight-lipped Englishmen had to say to each other and to Oom Piet while they were together in the cart is best left to the imagination; it is enough to say that they took Oom Piet’s advice and temporarily locked him up in town. Later, he was freed on parole but had to while away the time in his tuishuis (a small house in which farmers stayed during infrequent visits to town) in Pastorie Street with his family, reporting to the British twice a day. After the war Oom Piet went back to his farm. One evening he was standing on the porch when he noticed a flashing light. When he and Tant Chrissie investigated, they found out that it was caused by the windpump’s steel blades reflecting the moonlight. And so they discovered a possible source of the so-called heliograph messages. Or so the story goes. Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ Glorious Gables

Introduction

Introduction

The correctness of the term ‘Cape Dutch architecture’ has often been questioned, but a better and clearer one has never been agreed upon. Museum director Dr. Jan van der Meulen, in a doctoral thesis at a German university in the sixties, tried to prove that it should rather be called Cape German. As a result he was often referred to as ‘doktor Von der Moilen’.

The ‘Dutch’ of the term was probably introduced by English speakers and must have referred to ‘the architecture of the Dutch period’ rather than suggesting a ‘Dutch’ stylistic origin. Such an origin – apart from a certain German influence, if you wish – can certainly be detected in certain details, like gable design and door and window types, but is not at issue in our context. The Cape was Dutch, and not German. And if there are two things that characterize early Cape colonial architecture (if we must use an alternative term), it must be its highly recognizable quality and its strong homogeneity. Within a few decades the little settlement at the Cape developed a domestic architecture that has an unmistakeably local character, of which the highly uniform elements persisted for over a century and a half – well into the British period, in places well into the second half of the nineteenth century. There may well be similarities with domestic architecture in parts of Europe, but no Cape farmstead or townhouse can be mistaken for anything similar over there, not even in the Netherlands or its other former colonies.

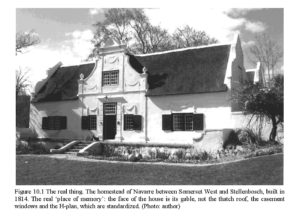

Due to this high degree of uniformity (the causes of which are discussed further on) it is comparatively easy to describe the main elements of this style. These are, first of all, its standardized plan forms and, secondly, the decorative ‘overlay’, notably the gable. The gable is often regarded as the outstanding feature of Cape Dutch architecture. But this is not entirely correct. A Cape farmhouse without a centre gable (and there are hundreds of them) is still undeniably Cape Dutch. But without what we call the ‘letter-of-the-alphabet’ plan it certainly is not. But granted: where ‘places of memory’ – iconic features – are discussed, the chances are we are referring to the Cape gable. Let us therefore first get the development of the unique wing-type plan formation out of the way, while being aware that, while it is this that makes a building ‘Cape Dutch’, in itself it never became a ‘place of memory’.

The homestead of Navarre between Somerset West and Stellenbosch, built in 1814. The real ‘place of memory’: the face of the house is its gable, not the thatch roof, the casement windows and the H-plan, which are standardized. Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ Memories Of Heroines: Bitter Cups And Sourdough

Introduction

Introduction

To write about concentration camps as places of remembrance is an exercise that any curious psychologist will find interesting. While the task of the psychologist is to listen to every memory with earnest compassion, she also has to regard what she is told with suspicion. The psychological undertaking starts with a focus on the conscious memory, but attention is then diverted to those things that are not yet remembered. The project about places of remembrance becomes the project of forgotten places – the holes, the cracks, the gaps, the pauses, the hidden, and, especially, the silences.[i]

When concentration camps are spoken about in this project of forgotten places, it is eventually less about the concentration camps themselves than about the way in which such places become places of remembrance – or not. The question is not so much about WHAT you remember – that is merely the beginning of the process. Other questions become more significant: Who is doing the remembering? When do they remember? Why do they remember? For whom do they remember? And, of course: what are they forgetting?

Waves of memory and forgetting

With these questions in mind, and with regard to memories of concentration camps in the South African War (1899-1902), the first question is when, and under what circumstances, are these camps remembered? Historians and social commentators[ii] give a clear indication of how memories – and forgetting – of the camps come and go in waves.

In the first wave of remembrance (1902-1905) it is immediately apparent how selfconscious the remembering was, and how purposeful the attempts not to forget. E.N. Neethling, in her 1902 account of the war significantly called Should we forget? gives the following reasons for writing the book:

… to induce all good men and women to see and acknowledge the horror, the wickedness of war … so that we realise that we, Afrikanders of the republics and the colonies from the Cape to the Zambesi, are today, more than we ever were before, ONE PEOPLE.[iii]

Neethling’s plea not to forget, even in the early stages, seems to be part of a nationalist project. In the far more emotional Dutch edition of her book, published in 1917 and aimed at Afrikaans readers, there is a bitter command on the title page: NB: This book is not for those who want to forget.[iv] Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ The Voortrekker In Search Of New Horizons

To forget and – I will venture to say – to get one’s history wrong, are essential forces in the making of a nation.[i]

To forget and – I will venture to say – to get one’s history wrong, are essential forces in the making of a nation.[i]

We are marshalled into two lines – boys to one side, girls to the other. I am wearing a long volkspelerok, a lilac folk dress the exact shade of jacaranda blooms, dutifully sewn by my gran Mémé. I feel the traditional white lace kerchief scratching my neck, my feet resisting the pinch of my brand-new black school shoes, neatly buckled over a pair of white socks. Earlier this morning I took down the frock from where it was hanging, covered in plastic and reeking of mothballs, next to my virginal white Holy Communion dress. Sister Boniface bends over the record player. Her Dominican nun’s habit is daringly fashionable, the hem barely covering her knees. As the first chords of Afrikaners is plesierig fill the air, we take up our positions. Sister Boniface puts her hands around sister Modesta’s waist, and they twirl away.

In the singing class, we are taught ditties from the FAK songbook, a treasure trove of light Afrikaans song: My noointjie-lief in die moerbeiboom; Wanneer kom ons troudag Gertjie; Sarie Marais… Sister Boniface sings in perfect Afrikaans, tinged with a melodious Irish accent – tranforming the dust and plains of our language into moss and peat.

At the end of standard five I leave the Afrikaans convent school (the only Afrikaans convent in the world!) and move on to a big Afrikaans girls’ school. The principal conducts the standard six girls to a bronze cast of Anton van Wouw’s Die Noitjie van die Onderveld (‘Simple country girl’).

The Voortrekker girl stands about one foot (30cm) tall on a stone podium; feet together, hands crossed. Her head is slightly bowed; the small, bronze face barely visible and shaded by her kappie (bonnet). There is something despondent about her stance. ‘This, girls,’ the principal informs us, ‘is an example of the demeanour of a respectable young Afrikaans lady – proper, humble, chaste.’

However, at this school, the Voortrekker girls wear neither long dresses, nor bonnets. They are robust and rowdy, with muscular hockey calves and ruddy cheeks. After school they march and salute in their brown militaristic uniforms, singing cheery songs about camp fires and magtige dreunings (mighty rumblings)[ii]. I soon realise that the nuns, despite their brave efforts to turn me into a culturally authentic Voortrekker girl, have failed dismally. Here my knowledge of volkspele steps and FAK songs is meaningless.

I struggle to get a grip on the more subtle, underlying cultural codes. Due to my European Catholic background, I remain an outsider, and I am confronted with an impenetrable Afrikaans ‘laager’; for the first time I hear about the Roomse gevaar (the so-called Roman Catholic ‘menace’), the Swart Gevaar (Black ‘danger’), the Rooi Gevaar (Red ‘onslaught’). I realise that I am not an Afrikaner, even though my Flemish parents speak Afrikaans to us at home. I discover that I could never be one of them, no matter how hard I tried. I come to understand that my mother tongue is not the language of my mother, which makes all the difference.

Now, almost thirty years later, I shake my head in disbelief as I peruse a Sanlam advertisement in Insig.

‘Meet the New Voortrekkers’, the advertisement proclaims, introducing readers to a group of young, confident, multiracial and androgynous artists. Long forgotten is the chaste and humble country girl. Forgotten too the militaristic and exclusive youth movement standing for racial and cultural purity. The only requirement is that Die Taal (‘The Language’) be spoken with pride. Clearly the Voortrekker, as a locus of remembrance, is also a place of deliberate forgetting.

Though national identity has often been regarded as God-given, and therefore imagined as something natural and primordial, it is not generally acknowledged as a relatively modern notion – namely that of a fictitious community construed in a premeditated and deliberate fashion, usually in times of crisis when the survival of a particular society was at stake.[iii] As such, the Afrikaners presently occupy an interesting position, seeing that they used to be a rather undefined and divided ethnic group, once self-fashioned as a nation, and now demoted to only one of many African tribes whose tribal adherence presents a threat to the integrity of the unstable postcolony. From nation to tribe – moreover, a tribe with pariah status! A change of this order (in a community for whom self-determination has always served as a historical metanarrative) must of necessity inflict traumatic wounds to the collective self-concept. This liminality (between ethnicity and nationality, tradition and global modernity, dominance and disadvantage, colonialism and postcolonialism) is precisely what interests me with regard to the image of the Voortrekker. It is an image that has undergone significant changes: originating from historic events in the 19th century, becoming an icon of the Volk (Nation) in the 1930s, and finally evolving into a symbol of a more inclusive, cynical, militant and/or critical understanding of the Afrikaner’s role in the New South Africa. Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ English

1.

1.

There is something rather uneasy about the thought of English as a space of memory or memorialisation for Afrikaans. One can’t easily dispel a vague feeling of embarrassment at the idea that bilingualism features prominently in the specific language-memories of Afrikaans communities. English and Afrikaans are strange bedfellows: over time the relationship has been marked, either simultaneously or in turn, by admiration, amazement and reproach – and this continues right into the present. Of course, the complex relationship between the two languages and the two language communities dates back quite a long way. After 1806 the Cape was no longer Dutch, but the Dutch-speaking inhabitants stayed on. The British government that took constitutional control of the Cape after 150 or so years of Dutch East India Company rule, was obliged to seek a way of peaceful coexistence between the earlier established Dutch community and the new colonists. From the very beginning of European settlement everything that is characteristic of language contact situations was there. Afrikaans is the product not only of gradual language shift or dialect change, but also of the sustained interaction with indigenous languages, with slave languages and with English.

As early as 1910, eight years after the end of the Anglo-Boer war, the decision on official languages in the newly established Union of South Africa reflected the reality of two strong, separate language communities (notably, the indigenous African languages were not considered at the time). In spite of a British victory in 1902 over the largely Dutch-speaking Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State,[i] and their inclusion in a consolidated British colony, a compromise arrangement was accepted when it came to the language policy of the Union. Rather than following a winnertakes-all principle that would recognise English only, both Dutch and English were made official languages. In 1925 – fifty years after the establishment of the ‘Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners’ (GRA) in Paarl with the explicit aim of propagating Afrikaans as a language in its own right – Afrikaans replaced Dutch as an official language. Then already the relationship between Afrikaans and English and between the language communities that were identified by each of these languages showed tell-tale signs of an ambivalent history. The introduction of Afrikaans as an official language was preceded by almost 100 years of its sporadic usage in popular texts that illustrated local language variation, specifically the colloquial Cape Dutch.[ii] For those who had been educated in Dutch and could read and write the language well, Afrikaans instead of Dutch as an official language, was hardly acceptable. For them, Dutch was the standard language; Afrikaans did not have the required kind of social and educational prestige. Others preferred English as the language of literacy and social progress, and thus chose to migrate from Dutch to English. For many living in the rural districts Afrikaans had become their only language; it had, however, never been the only language in any part of the country. For this reason, Afrikaans can never be considered without contrasting it and taking into account its relation with the other South African languages; one can hardly think of Afrikaans in South Africa without some or other contrast to Dutch and finally also to English, the only other Germanic language in the country.

A large part of the 20th century’s memory of the relationship between English and Afrikaans is coloured by the memory of a war. After 1866, following the discovery of mineral wealth in the interior beyond the colonial borders, the British policy of non-expansion was revised. The young Republics of the Transvaal (ZAR) and the Free State that were established on an ideal of independence from British government, became interesting to British statesmen like Rhodes and Milner in a new way. It was not the unequal competition between British troops and Boer soldiers for control over gold and diamond fields that became prominent in the collective memory; the aspect of the conflict between Boer and Brit (1899-1902) that shaped attitudes towards and memories of English for more than fifty years afterwards, was the hardships that women and children endured at the hands of members of the British forces. Grundlingh[iii] points out that a shared language contributed significantly to the development of Afrikaner unity as did other factors such as the perception of a shared past, and shared religious convictions and practices. Even so, in the process of rebuilding infrastructure and communities before and after the unification of 1910, and in the political development of the early 20th century, white English and Afrikaans communities were dependent on each other. For Afrikaners, English was friend and foe, ally and oppressor, language of education and domination, sign and signal of what could be achieved and what was unattainable. Read more