Chomsky: The US And Israel Are Standing In The Way Of Iran Nuclear Agreement

During the first few decades of the post-war era, the U.S. considered Iran one of its closest geostrategic allies, especially after the CIA overthrew Iran’s democratically elected government in 1953 and restored Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as Iran’s leader. However, since the 1979 revolution, which abolished the monarchy and established an Islamic republic, the U.S. and Iran have been mortal enemies, largely due to the role that Israel occupies in the region. In this context, during the last couple of decades, the thorniest issue in the U.S.-Iran relationship has been Tehran’s nuclear program, which, Iran says, is focused on energy, not weapons. Israel has been adamantly opposed to the program, even though it is accepted beyond dispute that Israel itself is a nuclear power. In 2015, Iran and several other countries, including the United States, reached the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreement, according to which Iran was willing to dismantle much of its nuclear program and open its facilities to nuclear inspections in exchange for billions of dollars of relief support. However, the Trump administration withdrew U.S. support from the agreement — and Israel continued its policy of sabotage and assassination of scientists.

Current talks between Washington and Tehran’s rulers to restore the 2015 nuclear agreement have been stalled, and there is little hope that progress will be made any time soon. Naturally, the U.S. places the blame on Tehran. However, U.S. propaganda grossly distorts the reality of the situation, Noam Chomsky points out in this exclusive interview for Truthout. The barriers to diplomacy are none other than Israel and the United States, says Chomsky.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, the U.S. and Iran are at odds with each other, having difficulty even talking to each other. Why do they hate each other so much, and how much of a role does Israel’s shadow play in this continuous drama?

Noam Chomsky: At the risk of sounding like a broken record, I’d like to say a few words, once again, on why I feel that the entire framework in which this issue is discussed is seriously distorted — yet another tribute to the enormous power of the U.S. propaganda system.

The U.S. government has been telling us for years that Iranian nuclear programs are one of the gravest threats to world peace. Israeli authorities have made it clear that they will not tolerate this danger. The U.S. and Israel have acted violently to overcome this grave threat: cyberwar and sabotage (which the Pentagon regards as aggression that merits violence in self-defense), numerous assassinations of Iranian scientists, constant threats of use of force (“all options are open”) in violation of international law (and if anyone were to care, the U.S. Constitution).

Evidently, it is regarded as a most serious issue. If so, we surely want to see whether there is some way to lay it to rest. There is: Establish a nuclear weapons-free zone (NWFZ) in the Middle East, with inspections — which, we know, can work very well. Even U.S. intelligence agrees that before the U.S. dismantled the joint agreement on nuclear weapons (JCPOA), international inspections of Iran’s nuclear program were successful.

That would solve the alleged problem of Iranian nuclear programs, ending the serious threat of war. What then is the barrier?

Not the Arab states, which have been actively demanding this for decades. Not Iran, which supports the measure. Not the Global South — G-77, 134 “developing nations,” most of the world — which strongly supports it. Not Europe, which has posed no objections.

The barrier is the usual two outliers: the U.S. and Israel.

There are various pretexts, which we may ignore. The reasons are known to all: The U.S. will not allow the enormous Israeli nuclear arsenal, the only one in the region, to be subject to international inspection.

In fact, the U.S. does not officially recognize that Israel has nuclear weapons, though of course it is not in doubt. The reason, presumably, is that to do so would invoke U.S. law, which, arguably, would render the massive U.S. aid flow to Israel illegal — a door that few want to open. Read more

Noam Chomsky: The War In Ukraine Has Entered A New Phase

Seven months on, the war in Ukraine has entered a new phase. Ukrainian forces are running a counteroffensive in the east and south regions of the country while Russia is still bent on annexation plans. Meanwhile, the West, with the U.S. at the forefront, continues with its explicitly stated strategy of weakening Russia to the point of regime collapse, thereby leaving no room for negotiations. All these developments indicate that peace remains distant in Ukraine and that the war may in fact be poised to become even more violent. Worse, argues Noam Chomsky below in an exclusive interview for Truthout, congressional hawks are increasing the risk of terminal war with the Taiwan Policy Act of 2022, which was just recently approved by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and appears to be modeled on programs from prior to the Russian attack that were turning Ukraine into a de facto NATO member.

Chomsky is institute professor emeritus in the department of linguistics and philosophy at MIT and laureate professor of linguistics and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Program in Environment and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. One of the world’s most-cited scholars and a public intellectual regarded by millions of people as a national and international treasure, Chomsky has published more than 150 books in linguistics, political and social thought, political economy, media studies, U.S. foreign policy and world affairs. His latest books are The Secrets of Words (with Andrea Moro; MIT Press, 2022); The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power (with Vijay Prashad; The New Press, 2022); and The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic and the Urgent Need for Social Change (with C. J. Polychroniou; Haymarket Books, 2021).

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, after seven months of conflict, Russia and Ukraine find themselves in a situation that is hard to get out of. Russia is suffering great losses, and a recent Ukrainian counteroffensive has recaptured dozens of towns and villages in the northeast of the country. Under these circumstances, it seems that neither side is eager to pursue a peace settlement. Firstly, are you surprised by Russia’s problems on the battlefield, and, secondly, do you agree with the statement made recently by the minister in charge of the Hungarian Prime Minister’s Office that Moscow still has a major advantage over Kyiv and that it can declare victory whenever it wants?

Noam Chomsky: First, let me make it clear that I have nothing original to say about the military situation, and have no expert knowledge in this area. What I know is what’s reported, almost entirely from Western sources.

The general picture is that Russia has suffered a devastating defeat, demonstrating the utter incompetence of the Russian military and the remarkable capacities of the Ukrainian army provided with advanced U.S. armaments and detailed intelligence information about the disposition of Russian forces, a tribute to the courage of the Ukrainian fighters and to the intensive U.S. training, organization and supply of the Ukrainian army for almost a decade.

There’s plenty of evidence to support this interpretation, which is close to exceptionless apart from detail. A useful rule of thumb whenever there is virtual unanimity on complex and murky issues is to ask whether something is perhaps omitted. Keeping to mainstream Western sources, we can indeed find more that perhaps merits attention.

Reuters reports a “western official” whose assessment is that:

‘There’s an ongoing debate about the nature of the Russian drawdown, however it’s likely that in strict military terms, this was a withdrawal, ordered and sanctioned by the general staff, rather than an outright collapse…. Obviously, it looks really dramatic. It’s a vast area of land. But we have to factor in the Russians have made some good decisions in terms of shortening their lines and making them more defensible, and sacrificing territory in order to do so.’

There are varying interpretations of the equipment losses in the Russian flight/withdrawal. There is no need to review the familiar picture. A more nuanced version is given by Washington Post journalists on the scene, who report scattered and ambiguous evidence. They also review online video and satellite imagery indicating that the destroyed and abandoned military vehicles may have been at an equipment hub. Examining the videos, Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, former commander of U.S. Army Europe, concludes that the destruction was mostly at a staging area where “Russian forces stopped for fuel or were waiting for a mission when they fled,” the total amounting to a tank company that typically has about 10 or 11 tanks.

As one expects in a war zone, there is ample ambiguity, but little doubt that it was a major victory for Ukraine and its U.S.-NATO backers. I don’t think that Putin could simply “declare victory” after this humiliating setback, as the Hungarian prime minister suggests. On the prospects for a peace settlement, so little is reported or discussed that there is little to say.

Little, but not nothing. In the current issue of Foreign Affairs, the major establishment journal, Fiona Hill and Angela Stent — highly regarded policy analysts with close government connections — report that:

‘According to multiple former senior US officials we spoke with, in April 2022, Russian and Ukrainian negotiators appeared to have tentatively agreed on the outlines of a negotiated interim settlement. The terms of that settlement would have been for Russia to withdraw to the positions it held before launching the invasion on February 24. In exchange, Ukraine would promise not to seek NATO membership and instead receive security guarantees from a number of countries.’

On dubious evidence, Hill and Stent blame the failure of these efforts on the Russians, but do not mention that British Prime Minister Boris Johnson at once flew to Kyiv with the message that Ukraine’s Western backers would not support the diplomatic initiative, followed by U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, who reiterated the official U.S. position that Washington’s goal in the war is to “weaken” Russia, meaning that negotiations are off the table. Read more

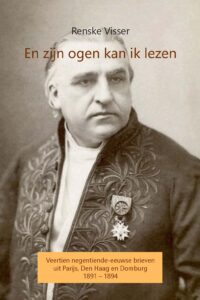

Renske Visser – En zijn ogen kan ik lezen. Veertien negentiende-eeuwse brieven uit Parijs, Den Haag en Domburg 1891-1894

Donderdag, 17 ix 1891

Lieve tante Martha,

Omdat u mij vroeg u in kennis te stellen van onze wederwaardigheden in Parijs, schrijf ik u deze brief. Thomas is na onze aankomst in het hotel gaan rusten. Ik kan de rust niet vinden, het lukt me zelfs niet een boek ter hand te nemen. Daarom heb ik besloten u te schrijven.

U weet hoe zeer ik aarzelde om samen met Thomas deze treinreis te maken. Omdat hij op zijn standpunt bleef staan, heb ik mijn twijfel laten varen. Na vandaag nemen mijn zorgen om zijn gezondheid toe. Toch wil ik met hem blijven hopen dat het een goed besluit is geweest van de geneesheer van het Johannes de Deo om voor Thomas een afspraak te maken met die Franse neuroanatoom. Thomas vestigt al zijn hoop op professor Charcot. Morgen bezoeken we het Hôpital de la Salpêtrière. Ik hoop dat deze voor hem zo afmattende reis niet vergeefs is geweest.

Toen de trein hedenmiddag het Gare du Nord binnenreed, zag ik hoe moeizaam Thomas zich oprichtte na de langdurige zit. Zijn ledematen waren zo verstijfd dat het leek of hij het dubbele aantal jaren van zijn leeftijd telde. Zijn stem klonk dof van vermoeidheid toen hij een kruier wenkte. Ondanks de wandelstok die hij onlangs op het Noordeinde gekocht heeft, liep hij alsof hij te veel alcohol had genuttigd.

Het was een voorrecht dat het rijtuig van het Hôtel du Louvre voor het station op ons wachtte. Echter, bij het instappen deed er zich een incident voor waardoor ik hevig ontsteld raakte. De koetsier vroeg mij of hij mijn vader kon assisteren. Om te voorkomen dat Thomas dit hoorde, siste ik de man toe: ’Mon mari!’ Vanzelfsprekend verontschuldigde hij zich, maar het leed was reeds geschied. Of Thomas het verstaan heeft? Hij was zwijgzaam gedurende de rit. Al duurde het geruime tijd voor ik kalmeerde, ik hield mijn mond om hem niet nodeloos te kwetsen. Op de hotelkamer ging hij zonder zich uit te kleden op bed liggen, terstond viel hij in een diepe slaap. Nadat ik hem toegedekt had, heb ik zo geruisloos mogelijk de koffers uitgepakt.

Nu zit ik bij het venster met uitzicht op de Rue Saint-Honoré en de Comédie Française. Als ik naar rechts kijk, zie ik de Place Royal waar het een komen en gaan is van mensen tussen het Palais en het Louvre. Deze avond zullen we ons tussen hen voegen als we naar de Opéra gaan. De Opéra zal voor mij de beste afleiding zijn om de zorgen om Thomas te vergeten. Ik hoop maar dat hij niet te laat wakker wordt.

Lieve tante, het hotel en onze ruime hoekkamer op de eerste etage zijn werkelijk magnifiek. Voor Thomas is het ideaal dat er een lift aanwezig is. Ik dank u en oom George dat u ons dit hotel heeft aanbevolen. Ik kan hier beslist een paar maanden verblijven. Als Thomas in het hospitaal verpleegd wordt, hoop ik Parijs te bezoeken. Het is alweer zo lang geleden dat wij hier geweest zijn. Het is werkelijk fameus dat het Louvre op kuierafstand ligt. Weet u dat de Jardin du Luxembourg opengesteld is voor publiek? Ik verheug me erop daarheen te gaan. Terwijl ik dit neerschrijf, voel ik me beschaamd dat ik me zo uitdruk, maar zegt oom George niet altijd dat wij het aangename met het nuttige moeten verenigen?

Thomas zal aanstonds wakker worden. Daarom groet ik u. Adieu, lieve tante, ik hoop dat het u en oom George zeer goed mag blijven gaan, evenals onze geliefde dochter Isabelle. Kust u ons kleine meisje van ons?

Uw liefhebbende nicht,

Laura

—

Renske Visser – En zijn ogen kan ik lezen. Veertien negentiende-eeuwse brieven uit Parijs, Den Haag en Domburg 1891-1894

Rozenberg Publishers, Amsterdam, 2021. ISBN 978 90 361 0658 0 – 92 pagina’s – Euro 12,50

Omslag & DTP: BuroBouws, Amsterdam

Verschenen 17 september 2022

Stichting HouseMartin

Dankzij donaties van fondsen en particulieren opent Stichting HouseMartin in het najaar van 2022 aan de Hooftskade in Den Haag de deuren van RespijtHuis HouseMartin waar daklozen kunnen herstellen van een griep, revalideren na een operatie of waar zij in een enkel geval de laatste levensdagen kunnen doorbrengen.

Door het kopen van En zijn ogen kan ik lezen draagt u bij aan de voortgang van RespijtHuis HouseMartin, een kleinschalig logeerhuis dat met inzet van vrijwilligers uit verschillende culturen een warm nest wil bieden aan de meest kwetsbaren in onze samenleving die geen plek hebben om het hoofd neer te leggen bij ziekte.

Website: https://respijthuishousemartin.com

Jean-Martin Charcot (Parijs, 29 november 1825 – Morvan, 16 augustus 1893) was een Franse arts die wordt beschouwd als een van de grondleggers van de neurologie.

Na aan de Sorbonne gepromoveerd te zijn met als specialisme gewrichtsreuma, ging hij werken als ziekenhuisarts. Na enige jaren keerde hij terug naar Parijs, waar hij werd benoemd tot hoogleraar in de pathologische anatomie. Hij verrichtte zeer veel onderzoek naar anatomie en de pathologie van het zenuwstelsel en ontdekte de ziekte amyotrofe laterale sclerose (ALS). Ook toonde hij aan dat multiple sclerose en de ziekte van Parkinson twee verschillende ziekten waren. De ziekte van Charcot-Marie-Tooth, een perifere zenuwziekte is naar hem genoemd samen met Pierre Marie (1853-1940) en Howard H. Tooth (1856-1926). In 1882 werd speciaal voor Charcot de eerste leerstoel voor ziekten aan het zenuwstelsel ingesteld aan het Hôpital de la Salpêtrière (Parijs).

Als dank en erkenning voor zijn werk werd hij in 1883 benoemd tot lid van de Académie de médecine en de Académie des sciences.

In de latere jaren van zijn carrière deed hij ook onderzoek naar de verschijnselen van hysterie, waarvoor hij onder andere hypnose gebruikte. Ook na zijn overlijden was Charcot van invloed op de psychiatrie en psychoanalyse. Veel van Charcots kennis werd namelijk overgenomen door zijn leerling/student Sigmund Freud. Ook Alfred Binet en Georges Gilles de la Tourette studeerden onder Charcot.

Bron: nl.wikipedia.org

Noam Chomsky & Robert Pollin: Humanity’s Fate Isn’t Sealed — If We Act Now

We live in extraordinarily dangerous times. Climate breakdown is upon us, yet nation-states and their leaders continue to pursue policies based on “national security” and the pursuit of geopolitical objectives. The transition to a clean and sustainable global energy landscape is hampered both by powerful interests linked to the fossil fuel economy and lack of international cooperation. In fact, the war in Ukraine, which runs on fossil fuels, is not only delaying climate action but has increased reliance on the very energy sources that drive global warming and poison the planet. Indeed, the war has been a godsend to the fossil fuel industry. “Drill, baby, drill” is back with a vengeance, and oil and gas companies are reaping unprecedented profits as families everywhere are struggling with skyrocketing energy costs.

To be sure, “savage capitalism,” as Noam Chomsky powerfully remarks in this exclusive joint interview with economist Robert Pollin, is unleashed today even more destructively than it has in the past. Yet, as Pollin so astutely points out, there are ways to tame global warming and make a successful transition to a sustainable future based on clean energy systems (which do not include nuclear power plants or so-called negative emission technologies). In fact, Chomsky and Pollin agree that, in large part, it is political will that stands in the way of securing the future of humanity and the planet. As Chomsky notes, the task of political education in the age of global warming is analogous to the task of philosophy as described by Ludwig Wittgenstein: “to show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.”

Noam Chomsky is institute professor emeritus in the department of linguistics and philosophy at MIT and laureate professor of linguistics and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Program in Environmental and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. One of the world’s most cited scholars in modern history and a critical public intellectual regarded by millions of people as a national and international treasure, Chomsky has published more than 150 books in linguistics, political and social thought, political economy, media studies, U.S. foreign policy and world affairs, and climate change.

Robert Pollin is distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. One of the world’s leading progressive economists, Pollin has published scores of books and academic articles on jobs and macroeconomics, labor markets, wages, and poverty, environmental and energy economics. He was selected by Foreign Policy Magazine as one of the “100 Leading Global Thinkers for 2013.” Chomsky and Pollin are co-authors of Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (2020).

C. J. Polychroniou: Noam, the systemic impacts of the war in Ukraine are enormous and they include economic shocks, food and energy security, geopolitical dimensions, and climate change. With regard to the latter, while it is difficult to make an accurate estimate of the climate impact of the war in Ukraine, it is crystal clear that it hinders current efforts to curb global warming and may even alter long-term strategy on climate action and action plan. How exactly are the war in Ukraine and the climate crisis connected, and why are governments doubling down on coal, oil and gas instead of doubling down on the clean energy transition?

Noam Chomsky: An independent observer looking at the world today might well conclude that it is being run by the fossil fuel and military industries, or by lunatics. Or both.

The scientific literature is harrowing, regularly showing that earlier dire warnings were too conservative and that we are careening towards disaster at a frightening pace. Even without reading the literature, anyone with eyes open can see that nature is saying “enough”: extreme heat, huge floods, devastating drought and severe water crises, large regions of the earth approaching the point where they will soon be uninhabitable.

How are we reacting? The basic character is captured by a clip from the marvelous satirical journal Onion — except that it is perhaps even beyond their imagination. It is real. And reported, with disbelief, in the mainstream:

‘In a paradox worthy of Kafka, ConocoPhillips plans to install “chillers” into the permafrost — which is thawing fast because of climate change — to keep it solid enough to drill for oil, the burning of which will continue to worsen ice melt.’

In his bitter antiwar essays, Mark Twain wielded his formidable weapon of satire against the perpetrators. But when he reached the renowned General Funston, he threw up his hands in despair: “No satire of Funston could reach perfection,” Twain lamented, “because Funston occupies that summit himself…. [He is] satire incarnated.”

What is happening before our eyes is unleashed savage capitalism as satire incarnated. Even Twain would be silenced.

To see what is at stake, consider some basic facts. “Arctic permafrost stores nearly 1,700 billion metric tons of frozen and thawing carbon. Anthropogenic warming threatens to release an unknown quantity of this carbon to the atmosphere.… Carbon dioxide emissions are proportionally larger than other greenhouse gas emissions in the Arctic, but expansion of anoxic conditions within thawed permafrost and soils stands to increase the proportion of future methane emissions. Increasingly frequent wildfires in the Arctic will also lead to a notable but unpredictable carbon flux.”

The carbon flux may be unpredictable in detail, but the resulting devastation is all too predictable in its general outline. How then does unleashed savage capitalism respond? Simple. Let’s employ our best brains to find ways to slow the melting down a little so that we can pour more poisons into the atmosphere for profit, and as a side effect, release those Arctic permafrost stores into the atmosphere more rapidly so as to make life unlivable.

Unfortunately, the observation generalizes. We find satire incarnate wherever we turn, even in marginal corners. Thus, one argument against solar energy is land use. A real problem, especially in the U.K., where golf courses take up over four times as much space as solar power, so we learn from political economist Adam Tooze’s invaluable Chartbook.

Satire incarnate is just the cutting edge. It brings out dramatically the elements of dominant economic institutions that are lethal if unleashed. It would be hard to conjure up a more fitting epitaph for the species — or more accurately, for the institutions that have become dominant as what we call civilization marches forward. Read more

We Need A World Without Borders On Our Increasingly Warming Planet

As we witness an increase in global migration amid a growing anti-immigrant sentiment, it is vital to remember that migration is mainly an outcome of political and economic processes associated with imperial conquest and capitalist globalization. Yet both liberal and conservative media exhibit similar bias toward migrations by treating them as problems that stem “from over there,” Harsha Walia points out in an exclusive interview for Truthout. Instead of accepting these false terms, Walia argues, we must recognize “there is no crisis at the border and there is no crisis of migration,” but instead a crisis of global apartheid.

Walia makes a case for a world without borders.

Harsha Walia, born in Bahrain and living in Vancouver, British Columbia, is a leading Canadian organizer and writer. In 2001, she co-founded the Vancouver chapter of No One Is Illegal, an anti-colonial, anti-racist and anti-capitalist migrant justice movement, and has been active in various migrant justice, Indigenous solidarity, feminist, anti-racist and anti-capitalist movements over the past two decades. She is the author of several books, including Undoing Border Imperialism and Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism and the Rise of Racist Nationalism.

C.J. Polychroniou: Europe and the United States are major destinations for people trying to escape war, political turmoil and poverty. In both places, the influx of “uninvited” people from foreign lands and cultures has generated an anti-immigration backlash and has led to increasingly harsh and even malicious policies in an attempt to deal with what is often referred to in the media and by experts alike as a “global migration and refugee crisis.” You have written extensively on the global migration crisis, so let me start by asking you to share with readers the way you understand and explain the factors behind this mass migration of people in the first part of the 21st century.

Harsha Walia: Conservatives and liberals alike conceive of immigration policy as an issue of domestic reform to be managed by the state. Language such as “migrant crisis,” and the often-corresponding “migrant invasion,” is a pretext to shore up further border securitization and repressive practices of detention and deportation. Such representations depict migrants and refugees as the cause of an imagined crisis at the border, when, in fact, mass migration is the outcome of the actual crises of capitalism, conquest and climate change.

In the U.S. context and the panic about the southern border, a long arc of dirty colonial coups, capitalist trade agreements extracting land and labor, climate change, and enforced oppression is the primary driver of displacement from Mexico and Central America. Hondurans, El Salvadorans and Guatemalans make up the fastest-growing proportion of people crossing into the U.S. Over the past decade, migration from these countries has increased fivefold. These perilous migrations are portrayed by liberal media as “not our problem” and stemming from “over there.” However, these migrations are “our problem” because they are inextricable from displacements created by U.S. dirty wars backing death squads across Central America and the counterinsurgency terror of the neoliberal “war on drugs.” From the war against the FMLN [Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front] in El Salvador to the coup to oust Honduran President Manuel Zelaya, there is an unbroken line of U.S. interventions in Central America. Migration is a predictable consequence of these continuous displacements, yet today the U.S. is fortifying its border against the very people impacted by its own policies.

As of 2016, new displacements caused by climate disasters are outnumbering new displacements as a result of persecution by a ratio of three to one. By 2050, an estimated 143 million people will be displaced in just three regions: Africa, South Asia and Latin America. El Salvador and Guatemala are among the 15 countries most at risk from environmental disaster, despite contributing the least to climate change. Rural and Indigenous farmers growing coffee, sugarcane, rice, beans and maize are facing crop losses, and successive droughts between 2014 and 2018 impacted over 2.5 million people in Central America.

Yet, displaced refugees — least responsible for and with the fewest resources to adapt to climate variations — face militarized borders in our warming world. A Pentagon-commissioned report from 2003 encapsulates this hostility to climate refugees: “Borders will be strengthened around the country to hold back unwanted starving immigrants from the Caribbean islands (an especially severe problem), Mexico, and South America.”

The U.S. is also funding immigration enforcement deep in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico to prevent people from even reaching the U.S.-Mexico border. Meanwhile, U.S.-based industries have polluted our world with 700 times more emissions than the entire Northern Triangle of Central America, and the overall ecological debt owed to poor countries by rich ones is estimated at $47 trillion. Rich countries grow at the ecological expense of poor countries.

The backlash against global migration has fueled the rise of far right movements throughout the Western world, though hostile views toward immigrants and refugees vary from country to country. Do you see migration as a crisis in itself, or a crisis of political opportunism? And how do you propose that governments deal with anti-immigration backlash?

While far right movements are immigration exclusionists — driven by a xenophobic and restrictionist ideology — the reality is that anti-immigration backlash is not intended to exclude all migrants, but, rather, to make the condition of migration, including the condition of migrant labor, more precarious. Border controls manufacture spatialized differences not to completely exclude all people but to capitalize on them. Neoliberal U.S. commentator Thomas Friedman says candidly, “We have a real immigration crisis and … the solution is a high wall with a big gate — but a smart gate.” Immigration enforcement is not only about the racial terror of outright exclusion but also about producing pliable labor — what Friedman is calling the “smart gate.”

Capitalism requires labor to be constantly segmented and differentiated — whether across race, gender, ability, caste, citizenship, etc. — and the border acts as a spatial fix for capitalism. Borders are not intended to exclude all people or to deport all people, but to create conditions of deportability, which in turn increases social and labor precarity. Workers’ labor power is captured by the border and this cheapened labor is exploited by the employer. The lack of full immigration status and the tying of visa status to an employer are key to creating pools of cheapened, indentured laborers. Workers are then kept compliant through threats of termination and deportation. According to one study, 52 percent of companies in the U.S. threaten to call immigration authorities on workers during union drives. The production of “migrant labor,” a group of workers in the nation-state but differentiated as non-citizen labor, demonstrates the centrality of bordering regimes to both coerce labor under racial capitalism and to restrict citizenship through anti-migrant xenophobia. Read more

Chomsky: Maintaining Class Inequality At Any Cost Is GOP’s Guiding Mission

The Republican Party has been steadily moving toward the extremely reactionary end of the scale over the past several decades. In some ways, Trump simply accelerated and finally cemented the GOP’s transition into an anti-democratic, proto-fascist political organization — although the Trump phenomenon is, in other ways, singular in political history, and its impact on U.S. politics and society will undoubtedly be felt for many years to come.

In the interview that follows, world-renowned scholar and public intellectual Noam Chomsky offers a tour-de-force analysis of the evolution of the U.S. political setting and the vital role that class warfare and repression have played in making corporate culture the dominant force, turning American society into a neoliberal dystopia. Chomsky also sheds light on why today’s GOP has turned U.S. politics into a culture war battle while pursuing policies that suppress social rights and strangle intellectual freedom, with Viktor Orbán’s “racist Christian nationalist proto-fascist government … hailed as the ideal for the future.” In addition, he assesses the political situation in connection with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act.

Chomsky is institute professor emeritus in the department of linguistics and philosophy at MIT and laureate professor of linguistics and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Program in Environment and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. One of the world’s most-cited scholars and a public intellectual regarded by millions of people as a national and international treasure, Chomsky has published more than 150 books in linguistics, political and social thought, political economy, media studies, U.S. foreign policy and world affairs. His latest books are The Secrets of Words (with Andrea Moro; MIT Press, 2022); The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power (with Vijay Prashad; The New Press, 2022); and The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic and the Urgent Need for Social Change (with C.J. Polychroniou; Haymarket Books, 2021).

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, the Republican Party has become an unabashedly anti-democratic political organization steering the U.S. toward authoritarianism. In fact, most GOP voters continue to support a political figure that sought to overturn a presidential election and seem to be enamored with Hungary’s strongman Viktor Orbán, who dismantled democracy in his own country. It is also of little surprise the way Republicans have responded to the FBI raid on Mar-a-Lago. The rule of law is of no consequence to them, yet conservatives charge that it is the Democrats who are moving the country toward authoritarianism. What’s shaping the character of the current Republican Party?

Noam Chomsky: What is unfolding before our eyes is a kind of classical tragedy, the grim conclusion foreordained, the march toward it seemingly inexorable. The origins are deep in the history of a society that has been free and bountiful for the privileged, awful for those who were in the way or cast aside.

A century ago, a stage was reached that has some similarity to today. In his classic study, The Fall of the House of Labor, labor historian David Montgomery writes that in the 1920s “corporate mastery of American life seemed secure.… Rationalization of business could then proceed with indispensable government support.” Inequality was soaring, along with corruption and greed. The vibrant labor movement had been crushed by Woodrow Wilson’s Red Scare, after decades of violent repression.

“Modern America had been created over its workers’ protests,” Montgomery continued, “even though every step in its formation had been influenced by the activities, organizations, and proposals that had sprung from working class life.” In the late 19th century, it seemed possible that the Knights of Labor, with its demand that those who work in the mills should own them, might link up with the radical farmers movement, the Populists, who were seeking a “cooperative commonwealth” that would free farmers from the tyranny of northeastern bankers and market managers. That could have led to a very different America. But it could not withstand state-corporate repression and violence.

A few years after the fall of the house of labor came the Great Depression. The labor movement revived and expanded, moving to large-scale industrial organization and militant actions. Crucially, there was a sympathetic administration, and a lively and often radical political environment. All of this laid the basis for the New Deal reforms that enormously improved American life and had repercussions in European social democracy.

The business world was split. Thomas Ferguson’s research shows that capital-intensive internationally oriented business accepted New Deal policies, while labor-intensive domestically oriented business was bitterly opposed. Their publications warned ominously of the “hazard facing industrialists” from labor action backed by “the newly realized political power of the masses,” topics explored in depth in Alex Carey’s Taking the Risks out of Democracy, which inaugurated the study of corporate propaganda.

As soon as the war ended, the business world launched a major assault on labor. It was impressive in scale, ranging from forced indoctrination sessions for the workforce even to taking over sports leagues. This was all part of the project of “selling free enterprise,” while the salesmen were happily gorging at the public trough where the hard and creative work of constructing the new high-tech economy was on the account of the friendly taxpayer.

Violent repression was no longer adequate to restoring the glory days of the ‘20s. More subtle means of indoctrination were devised, including “scientific methods of strike-breaking,” by now honed to a high art with the support of administrations since Reagan that barely pay attention to such labor laws as still exist.

The business campaign was expedited by the attack on civil liberties called “McCarthyism,” which led to expulsion of many of the most effective labor activists and organizers. Unions entered into a compact with capital to gain benefits for members (though not the public) in return for abandoning any significant role on the shop floor.

The regimented capitalism of the early postwar years has been called the “golden age of [state] capitalism,” with high and egalitarian growth. By the mid-‘60s popular activism was beginning to expose some of the long-concealed record of American history, and addressing some of its brutal legacy, again with the cooperation of a sympathetic administration.

By the early ‘70s, the established social order was tottering under the impact of the “Nixon shock” that undermined the postwar Bretton Wood system, stagflation, and not least, the growing threat of the popular movements that were civilizing the society. Elite concerns are well attested by major publications bracketing the mainstream spectrum of opinion.

At the left-liberal end, the liberal internationalists of the Trilateral Commission released their first publication, The Crisis of Democracy. The political flavor of the Commission is illustrated by the fact that the Carter administration was drawn largely from its ranks. The “Crisis” that concerned them was the activism of the ‘60s, which was mobilizing people to press their concerns in the political arena. These “special interests,” as they are called, were imposing too many pressures on the state, causing a crisis of democracy. The solution they recommended is more “moderation in democracy” by the special interests: minorities, women, the young, the old, workers, farmers, in short, the population, who are to be “spectators” not “participants,” in accord with liberal democratic theory (Walter Lippmann, Harold Lasswell, Reinhold Niebuhr, and other distinguished figures).

Unspoken is a crucial premise: the “special interests” are to be “put in their place,” as Lippmann advised, so that ample room is left for the “national interest” that is upheld by the “masters of mankind,” Adam Smith’s term for the business classes, who shape national policy so that their own interests are “most peculiarly attended to.” Smith’s words, which resonate loudly today. Read more