Average Global Temperature Has Risen Steadily Under 40 Years Of Neoliberalism

Since the advent of neoliberalism 40 years ago, societies virtually all over the world have undergone profound economic, social and political transformations. At its most basic function, neoliberalism represents the rise of a market-dominated world economic regime and the concomitant decline of the social state. Yet, the truth of the matter is that neoliberalism cannot survive without the state, as leading progressive economist Robert Pollin argues in the interview that follows. However, what is unclear is whether neoliberalism represents a new stage of capitalism that engenders new forms of politics, and, equally important, what comes after neoliberalism. Pollin tackles both of these questions in light of the political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, as most governments have implemented a wide range of monetary and fiscal measures in order to address economic hardships and stave off a recession.

Robert Pollin is distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and author of scores of books, including Back to Full Employment (2012), Greening the Global Economy (2015) and Climate Crisis and the Global Green new Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (co-authored with Noam Chomsky, 2020).

C.J. Polychroniou: Neoliberalism is a politico-economic project associated with policies of privatization, deregulation, globalization, free trade, austerity and limited government. Moreover, these principles have reigned supreme in the minds of most policymakers around the world since the early 1980s, and continue to do so. Is neoliberalism a new stage of capitalism?

Robert Pollin: Let’s first be clear on what we mean by “neoliberalism.” The term neoliberalism draws on the classical meaning of the word “liberalism.” Classical liberalism is the political philosophy that embraces the virtues of free-market capitalism and the corresponding minimal role for government interventions. According to classical liberalism, free-market capitalism is the only effective framework for delivering widely shared economic well-being. In this view, only free markets can increase productivity and average living standards while delivering high levels of individual freedom and fair social outcomes. Policy interventions to promote economic equality within capitalism — through, for example, taxing the rich, big government spending on social programs, or regulating market activities through, for example, decent minimum wage standards and regulations to prevent financial markets from becoming gambling casinos — will always end up doing more harm than good, according to this view.

For example, establishing living wage standards as the legal minimum — at, say $15 an hour or higher — would cause unemployment to rise, since, according to classical liberalism, employers won’t be willing to pay unskilled workers more than what the free market determines they are worth. Similarly, regulating financial markets will inhibit capitalists from undertaking risky investments that can raise living standards. Classical liberals will argue that the Wall Street Masters of the Universe are infinitely more qualified than government bureaucrats in deciding what to do with their own money. And if the Wall Street investors make dumb decisions, then so be it; let them fail. In that way, [classical liberalism says] the free market rewards smart decisions and punishes bad ones, all to the greater benefit of the whole society.

Now to neoliberalism: Neoliberalism is a contemporary variant of classical liberalism that became dominant worldwide around 1980, beginning with the elections of Margaret Thatcher in the U.K. and Ronald Reagan in the United States. At that time, it was certainly a new phase of capitalism. Thatcher’s dictum that “there is no alternative” to neoliberalism became a rally cry, supplanting what had been, since the end of World War II, the dominance of Keynesianism and social democracy in global economic policymaking. In the high-income countries of Western Europe and North America along with Japan, in particular, this Keynesian/social democratic version of capitalism featured, to varying degrees, a commitment to low unemployment rates, decent levels of support for working people and workplace conditions, extensive regulations of financial markets, public ownership of significant financial institutions and high levels of public investment.

Of course, this was still capitalism. Disparities of income, wealth and opportunity remained intolerably high, along with the social malignancies of racism, sexism and imperialism. Ecological destruction, in particular global warming, was also beginning to gather force over this period, even though few people took notice at the time. Nevertheless, all told, Keynesianism and social democracy produced dramatically more egalitarian as well as more stable versions of capitalism than the neoliberal regime that supplanted these models.

It is critical to understand that neoliberalism was never a project to replace social democracy with true free-market capitalism. Rather, contemporary neoliberals are committed to free-market policies when they support the interests of big business and the rich as, for example, with lowering regulations in the workplace and financial markets. But these same neoliberals become far less insistent on free market principles when invoking such principles might damage the interests of big business, Wall Street and the rich.

An obvious example is the historically unprecedented levels of support provided during the COVID recession to prevent economic collapse. Just in 2020 in the U.S. for example, the federal government pumped nearly $3 trillion into the economy, equal to about 14 percent of total economic activity (GDP) to prevent a total economic collapse. On top of that, the U.S. Federal Reserve injected nearly $4 trillion — equal to about 20 percent of GDP — to avoid a Wall Street meltdown. Of course, pumping government money into the U.S. economy, at a level equal to roughly one-third of total GDP, all in no more than one year’s time, completely contradicts any notion of free-market, minimal government capitalism.

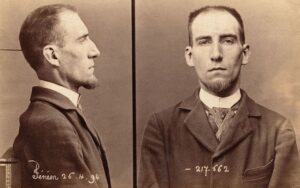

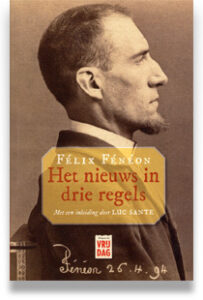

Félix Fénéon, kunstcriticus en anarchist

Dat de Franse dichter Laurent Tailhade behalve zijn avondmaaltijd een oog moest missen, was een meer dan sneu gevolg van de bomaanslag die kunstkenner en –criticus Félix Fénéon op 4 april 1894 pleegde op het restaurant van Hôtel Foyot aan de Rue de Tournon in Parijs.

Het was vooral sneu omdat Tailhade Fénéon persoonlijk kende en ook diens anarchistische opvattingen deelde. Zijn verwondingen weerhielden Tailhade er echter niet van in de jaren daarna in zijn werk het anarchisme volop uit te dragen.

Ministerie

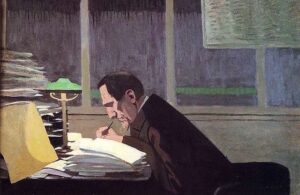

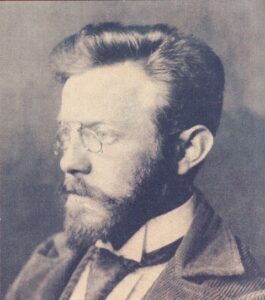

Félix Fénéon (1861-1944) groeide op in de Bourgogne maar vertrok al snel naar Parijs. Op zijn twintigste kreeg hij een baan als klerk op het Ministerie van Oorlog. Hij zou er dertien jaar blijven werken. Daarnaast redigeerde hij voor uitgeverijen werk van Arthur Rimbaud en Lautréamont. Met zijn dandyachtige voorkomen – puntbaard, wandelstok, zwarte cape – was hij in kunstkringen een opvallende verschijning. Wekelijks bezocht hij de populaire kunstsalon van Stéphane Mallarmé. Naast zijn baan op het ministerie werd hij kunstcriticus bij het tijdschrift La Libre Revue. Ook schreef hij gezaghebbende artikelen over kunst en literatuur voor bladen als La Vogue en La Revue wagnérienne. Hij was de ontdekker van de schilder Georges Seurat en was bevriend met de schilder Paul Signac, die hem op een schilderij vereeuwigde. Ook de kunstenaars Toulouse-Lautrec en Félix Valleton maakte portretten van Fénéon. Hij was een onvermoeibaar promotor van het werk Seurat en Signac, die beiden gezien worden als de wegbereiders van het pointillisme. Voor deze stijl en andere daaraan gelieerde kunststromingen bedacht Fénéon de term neonimpressionisme.

Anarchisten

Fénéon kreeg eveneens contacten in anarchistische kringen en hij ging schrijven voor het toonaangevende anarchistische tijdschrift L’En-Dehors van de anarchist Zo d’Axa en voor Revue anarchiste. Toen Zo d’Axa zijn toevlucht zocht in Londen nam Fénéon de redactie van L’En-Dehors over. Aan het tijdschrift werd onder meer meegewerkt door Octave Mirbeau. Jean Grave, Sébastien Faure, Bernard Lazare, Tristan Bernard en de Belgische anarchist Émile Verhaeren. Hij raakte bevriend met de Nederlandse anarchist Alexander Cohen en met ‘anarchist van de daad’ Émile Henry, die later de beruchte bomaanslag op het Café Terminus zou plegen. Soms logeerde Henry bij Fénéon of bij Cohen thuis. Al eerder had Fénéon Henry al eens aan een jurk geholpen, om in vermomming de politie te kunnen ontlopen.

Aanslagen

De uit Leeuwarden afkomstige Cohen (1864-1961) was na een redacteurschap bij Recht voor Allen van Domela Nieuwenhuis overhaast naar Parijs verhuisd. In Nederland werd hij gezocht wegens majesteitsschennis. Tijdens een rijtour van Koning Willem III had hij geroepen: ‘Leve Domela Nieuwenhuis! Leve het socialisme! Weg met Gorilla!’.

In Parijs ging hij schrijven voor de anarchistische bladen L’En-Dehors en Le Père peinard en werd hij correspondent voor Recht voor Allen. In de Franse hoofdstad werden Fénéon en Émile Henry zijn beste vrienden.

Henry wilde in 1892 de eisen van stakende mijnarbeiders bij de Carmoux mijnmaatschappij kracht bijzetten en plaatste een bom bij het kantoor van de maatschappij in Parijs. De bom werd echter ontdekt en meegenomen naar een politiebureau in de Rue des Bons-enfants. Daar ontplofte de bom alsnog waarbij vijf politiemannen om het leven kwamen.

Zijn volgende aanslag was een wraakneming voor de executie van de anarchist Auguste Vailllant, ter dood veroordeeld wegens het plegen van een bomaanslag op de Chambre des Députés, de Kamer der Afgevaardigen. Op 12 februari 1894 plaatste Henry een bom onder een tafeltje in het drukbezochte Café Terminus bij het Gare St. Lazare. Eén persoon kwam om het leven en twintig mensen raakten gewond. Henry werd gearresteerd en in mei 1894 terechtgesteld.

Restaurant

Restaurant

Fénéon, die vond dat zijn eigen schriftelijke bijdragen aan het verkondigen van de anarchistische boodschap niet voldoende effect hadden, nam zich voor de vertegenwoordigers van de bourgeoisie in het hart te treffen. Op 4 april 1894 verstopte hij een bom in een bloempot en toog ermee naar de zetel van de Franse senaat, gevestigd in het paleis in de Jardin du Luxembourg. Daar bleek hij echter niet in de buurt van het bewaakte gebouw te kunnen komen, waarop hij besloot de bom te plaatsen bij het tegenover gelegen Hôtel Foyot, een door veel parlementariërs bezochte eetgelegenheid. Hij plaatste de bloempot in de vensterbank van het restaurant, stak de lont aan en wandelde rustig naar de Place de l’Odéon, waar hij op de bus richting Clichy sprong. Door de ontploffing sneuvelden ramen en stortten kroonluchters van het plafond omlaag. Alleen de dichter Tailharde raakte gewond, het kostte hem een oog.

Huiszoeking

Vanwege zijn anarchistische activiteiten werd Fénéon al enige tijd door de politie in de gaten gehouden. Een dag na de aanslag doorzocht de politie zijn woning maar kon daar geen verdachte aanwijzingen ontdekken. De huiszoeking moest wel op een misverstand berusten, concludeerde de politie-inspecteur en bood excuses aan. Op het politiebureau ondertekende Fénéon een verklaring waarin hij ontkende aanhanger van het anarchisme te zijn, en vertrok naar zijn kantoor op het Ministerie van Oorlog. Daar bewaarde hij in een la van zijn bureau een fles kwikzilver en enige ontstekers – hem door Henry in bruikleen gegeven – die echter door de politie werden ontdekt. Dit en zijn anarchistische activiteiten waren voldoende om hem te arresteren. Met de aanslag op het Hôtel Foyot is hij echter nooit meer in verband gebracht.

Proces

Proces

De Franse regering was de aanslagen beu en vaardige een serie strenge wetten uit waarbij iedere anarchistische activiteit strafbaar werd gesteld. Dertig vooraanstaande anarchisten werd ‘organisatie van criminele activiteiten’ ten laste gelegd, onder wie Sébastien Faure, Jean Grave, Paul Reclus, Félix Fénéon en Alexander Cohen. Voor de Franse staat draaide dit ‘Procès des trente’ echter uit op een mislukking. Slechts acht beklaagden werden veroordeeld, vier van hen bij verstek, onder wie Reclus en Alexander Cohen. De laatste had inmiddels de wijk naar Londen genomen. Pas in 1899 zou hij naar Parijs terugkeren.

Tijdens het proces wist Fénéon op vaak humoristische wijze aanklachten tegen hem te pareren. Bij een beschuldiging van een ‘nauw contact’ met de Duitse anarchist Kampfmeyer, antwoordde hij: ‘Ik spreek geen Duits en Kampfmeyer spreekt geen Frans. Hoe nauw moet dat contact dan geweest zijn?’ En toen hij beticht werd een vooraanstaande anarchist te hebben gesproken ‘achter een gaslantaarn’, was zijn antwoord: ‘Neem me niet kwalijk, Monsieur le Préfect, maar wat is de achterkant van een gaslantaarn?’ Fénéon werd vrijgesproken maar zijn baan op het ministerie moest hij wel opgeven.

Drie regels

Als redacteur kon hij aan de slag bij het vooraanstaande kunsttijdschrift La Revue Blanche. Ook daarin vestigde hij voortdurend de aandacht op het werk van Seurat en Signac en in 1900 organiseerde hij de eerste overzichtstentoonstelling van schilderijen van Seurat. In het tijdschrift publiceerde hij ook werk van Marcel Proust, Appolinaire, Paul Claudel en vertaalde hij Jane Austen en brieven van Edgar Allen Poe.

In 1906 ging hij voor de krant Le Matin de dagelijkse pagina faits divers samenstellen: berichten uit stad en provincie, die –zo was de opdracht – in de krant niet langer dan drie regels mochten zijn. Nieuwtjes over inbraken, ongelukken, crimes passionnel, moorden, branden en ander leed, werden door Fénéon geminimaliseerd tot gevatte beschrijvingen van het gebeurde, vaak met een kwinkslag of woordspeling, soms met kort commentaar. Hij puzzelde met woorden, zoals een dichter of liedjesschrijver. Ieder bericht vormt een verhaal op zich en roept vragen op over het hoe en waarom. Intrigerende, vermakelijke of hilarische, tragische of ontroerende berichten die in veel gevallen de aanzet tot een roman zouden kunnen zijn. De berichten zijn te vergelijken met de collages die Picasso en Braque jaren later uit gescheurde kranten samenstelden, maar doen ook denken aan de collages van Kurt Schwitters en aan de wijze waarop William Burroughs in de jaren vijftig kranten verknipte en omsmeed tot een roman. Dankzij het knipwerk van Fénéons vriendin zijn twaalfhonderd stukjes bewaard gebleven en in 2009 in boekvorm verschenen. Fénéon schreef de stukjes om in zijn onderhoud te voorzien, maar wellicht vond hij ook voldoening bij het in kaart brengen van het verval in de Franse samenleving. De lezer kon zelf zijn conclusie trekken.

In 1906 ging hij voor de krant Le Matin de dagelijkse pagina faits divers samenstellen: berichten uit stad en provincie, die –zo was de opdracht – in de krant niet langer dan drie regels mochten zijn. Nieuwtjes over inbraken, ongelukken, crimes passionnel, moorden, branden en ander leed, werden door Fénéon geminimaliseerd tot gevatte beschrijvingen van het gebeurde, vaak met een kwinkslag of woordspeling, soms met kort commentaar. Hij puzzelde met woorden, zoals een dichter of liedjesschrijver. Ieder bericht vormt een verhaal op zich en roept vragen op over het hoe en waarom. Intrigerende, vermakelijke of hilarische, tragische of ontroerende berichten die in veel gevallen de aanzet tot een roman zouden kunnen zijn. De berichten zijn te vergelijken met de collages die Picasso en Braque jaren later uit gescheurde kranten samenstelden, maar doen ook denken aan de collages van Kurt Schwitters en aan de wijze waarop William Burroughs in de jaren vijftig kranten verknipte en omsmeed tot een roman. Dankzij het knipwerk van Fénéons vriendin zijn twaalfhonderd stukjes bewaard gebleven en in 2009 in boekvorm verschenen. Fénéon schreef de stukjes om in zijn onderhoud te voorzien, maar wellicht vond hij ook voldoening bij het in kaart brengen van het verval in de Franse samenleving. De lezer kon zelf zijn conclusie trekken.

In Rouen heeft M. Colombe zich gisteren met één kogel gedood. In maart had zijn vrouw hem er drie in het lijf geschoten en de echtscheiding was op handen.

Met haar tachtig jaren werd Mme Saout uit Lambézellec stilaan bang dat de dood haar zou overslaan. Toen haar dochter even de deur uit was, knoopte zij zich op.

In Falaise verwelkomde oud-burgemeester M. Ozanne de deurwaarder Vieillot met geweerschoten om zich, na één treffer, het leven te benemen.

Jacquot, eerste bediende bij een kruidenier in Les Maillys, heeft zich en zijn vrouw om het leven gebracht. Hij was ziek, zij niet.

Zittend in de vensterbank van het open raam, reeg G. Laniel, negen, uit Meaux haar laarsjes dicht. Bijna. Tot zij achterover op de keien smakte.

(uit: Félix Fénéon, Het nieuws in drie regels, Antwerpen 2009)

Geruchten

Jarenlang deden nog geruchten de ronde dat de aanslag bij Hôtel Foyot het werk van Fénéon was geweest. Fénéon zelf heeft er nooit in het openbaar over gesproken en besteedde er geen aandacht aan. Slechts eenmaal bevestigde hij dat hij de dader was, in een gesprek met Kaya Batut, de vrouw van Alexander Cohen.

Noot

1. Vorig jaar werd in het Moma in New York een grote tentoonstelling aan Fénéon gewijd, waarop onder meer werk van Seurat en Signac te zien was.

Literatuur

Alexander Cohen, In opstand, Amsterdam 1932

John Merriman, The Dynamite Club, New Haven/London 2009

Félix Fénéon, Het nieuws in drie regels, Antwerpen 2009

Joan Ungersma Halperin, Félix Fénéon, Aesthete & Anarchist in Fin-de-Siècle Paris, New Haven/London 1988

Chomsky: Biden’s “Radical” Proposals Are Minimum Measures To Avoid Catastrophe

Looking at the state of the world, one is struck by the stark contradiction of progress being made on some fronts even as we are facing massive disruptions, tremendous inequalities and existential threats to humanity and nature.

In this context, how do we evaluate the qualities of progress and decline? How significant is political activism to progress?

In this exclusive interview, Noam Chomsky, one of the world’s greatest scholars and leading activists, shares his insights on the state of the world and the conundrum of activism and change, including the significance of the Black Lives Matter movement, the movement for Palestinian rights, the urgency of the climate crisis and the threat of nuclear weapons.

C.J. Polychroniou: It’s been said by far too many, including myself, that we live in dark times. And for good reasons. We live in an era where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, authoritarianism is a global political phenomenon, and life on Earth is entering a state of collapse. From that perspective, human civilization is on an inexorable course of decline and nothing but a radical overhaul of the way humans conduct themselves will save us from a return to barbarism. Yet, there are at the same time signs of progress on numerous fronts, which are hard to overlook. Societies are becoming increasingly multicultural and also more aware of and sensitive to patterns of racism and discrimination. In the light of all this, do we see the glass half empty or half full? Moreover, is it possible to evaluate the qualities of decline and progress scientifically, or do we have to rely purely on normative evaluations and value judgments?

Noam Chomsky: There are attempts to measure the contents of the glass. The best-known is the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, with the hands placed a certain distance from midnight: the end. Each year that Trump was in office, the minute hand was moved closer to midnight, soon reaching the closest it had ever been, then going beyond. The analysts finally abandoned minutes and turned to seconds: 100 seconds to midnight, where the Clock now stands. That seems to me a fair assessment.

The analysts identify three major crises: nuclear war, environmental destruction and the deterioration of rational discourse. As we’ve often discussed, Trump has made a signal contribution to each, and the party he now owns is carrying his legacy forward. They are also currently hard at work to regain power by overcoming the dread danger of a government of the people, with plenty of far right big money at hand. If the project succeeds, emptying of the glass will be accelerated.

There has indeed been progress on many fronts. It is startling to look back and see what was regarded as proper behavior and acceptable attitudes not many years ago, even written into law. While substantial, the progress has not, however, been sufficient to contain and reverse the continuing assault on the social order, the natural world and the climate of rational discourse.

Without disparaging the great activist achievements, it’s hard sometimes to suppress memory of an ironic slogan of the ‘60s: They may win the battles, but we have all the best songs.

The glass that is before our eyes is not an encouraging sight, to put it mildly. Take the state of the three major crises identified in the setting of the Clock.

The major nuclear powers are obligated by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

They are pursuing the opposite course.

In its latest annual survey, the prime monitor of global armament, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, reports that “The growth in total spending in 2020 was largely influenced by expenditure patterns in the United States and China. The USA increased its military spending for the third straight year to reach $778 billion in 2020,” as compared with China’s increase to $252 billion. In fourth place, below India, is the second U.S. adversary, Russia: $61.7 billion.

The figures are instructive, but misleading. The U.S. is alone in facing no credible security threats. The threats that are invoked in the calls for even more military spending are at the borders of adversaries, which are ringed with U.S. nuclear-armed missiles in some of the 800 U.S. military bases around the world (China has one, Djibouti).

Further threats, in this case quite real, are the development of new and more dangerous weapons systems. They could be banned by treaties, which were effective, until they were mostly dismantled by Bush II and Trump.

With Earth On Edge, Climate Crisis Must Be Treated Like Outbreak Of A World War

Humanity and the environment are under massive assault by global warming caused by human activities.

The new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report released today, August 9, 2021—the first of four that make up the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment report—reiterates in scientific language (it deals with the physical science basis of global warming) what we have already known for quite some time from scores of previous studies: humanity faces a climate emergency, global warming is human driven, major climate changes are irreversible, and time is running out to avoid a catastrophe of unimaginable proportions.

It is, nonetheless, an extremely valuable report because a damning indictment of humanity’s wholly destructive actions towards all life on Earth now carries the stamp of approval by the world’s most authoritative voice on climate science. And, ironically enough, the new IPCC’s 6th Assessment climate report is also approved by the very same entities—195 member governments—largely responsible, although surely not all to the same extent, for the looming global climate catastrophe.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres described the report as “a code red for humanity.” U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry said the report made clear the “overwhelming urgency of this moment.” And U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said the report is “sobering reading” and should serve as a “wake-up call” for global leaders ahead of the COP26 summit, which will be held in Glasgow from 31 October—12 November 2021.

The planet is expected to warm by at least 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2040, according to the IPCC’s latest findings. But the report also underscores the key point that, without “immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions,” even limiting warming to even 2 degrees “will be beyond reach.”

The IPCC’s latest report points to temperatures rising faster than previously thought. In fact, on current trends the world is moving fast towards 3 degrees Celsius.

Coincidentally, once the average global temperature rises 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level, the planet will experience a surge in climatic tipping points, resulting in fiercer heatwaves, melting ice, rising sea levels, and severe droughts.

Yet, the scientists behind the writing of the latest IPCC report say that the worse can be avoided if the world acts fast. In other words, rescuing the planet comes down to politics—and economics. And to human nature, one might add.

There is no doubt that the task ahead is exceedingly difficult, to say the least. A global existential crisis must be addressed in a world occupied by primarily egoistic and highly imperfect creatures; where the nation-state remains the primary political unit; and with an economic system in place that is destructive and unsustainable. Nonetheless, the odds can be overcome because it’s either survival or extinction. Reason must prevail, international cooperation needs to replace national antagonisms, and sustainability take priority over short-term profits.

All of the above are realizable goals through a political decision to move away from the fossil fuel economy and, in turn, to implement a green new deal on a global scale.

World War II was won through economic breakthroughs, technological cooperation, and the formation of a primary alliance against the Axis powers.

The climate crisis must be treated like a world war—World War III. Humanity and the environment are under massive assault by global warming caused by human activities. The biggest polluters on the planet—U.S., China, India, Russia, Japan, Germany—must form an alliance to lead the global economy away from fossil fuels as quickly as possible. The rich countries, which are responsible for the climate crisis, also have a responsibility to finance the bulk of the transition to a global green economy. Moreover, various studies have shown that financing the Global Green New Deal is not a particularly challenging task. UMass-Amherst economist Robert Pollin, for example, has argued that there are several large-scale funding sources for the greening of the global economy, and they include things such as carbon tax, the transfer of funds out of military budgets, lending programs introduced by Central Banks, and the elimination of all fossil fuel subsidies. He has also estimated, a figure corroborated by other similar studies, that the cost of the clean energy transformation would require an average spending of about $4.5 trillion per year between 2024 and 2050 (which is when most countries have committed to reaching zero emissions.

In sum, all is not yet lost, which is also the conclusion of the ICPP’s latest report. Of course, whether we can overcome the institutional, structural, and even intrinsic obstacles to designing a long-term, truly sustainable world economy remains to be seen. But if we convince ourselves that combatting the climate crisis is equivalent to fighting a world war, we do have a realistic chance of rescuing planet Earth.

Source: https://www.commondreams.org/earth-edge-climate-crisis-must-be-treated-outbreak-world-war

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change” and “Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet” (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors).

Is A Return To Barbarism Unavoidable?

A cursory glance at the state of today’s world will give pause to anyone wishing to celebrate humanity’s progress. In fact, evidence abounds that the possibility of a reversion to barbarism should not be rejected as too far-fetched.

We live in a period of great global complexity, confusion and uncertainty. We are in the midst of a whirlpool of events and developments that are eroding our capability to manage human affairs in a way that is conducive to the attainment of a political and economic order based on stability, justice and sustainability. Indeed, the contemporary world is fraught with perils and challenges that will test severely humanity’s ability to maintain a steady course towards anything resembling a civilized life.

For starters, we have been witnessing the gradual erosion of socio-economic gains in much of the advanced industrialized world since the late 1970, along with the rollback of the social state, while a tiny percentage of the population is wealthy beyond imagination that compromises democracy, subverts the “common good” and promotes a culture of dog-eat-dog world. The pitfalls of massive economic inequality were identified even by ancient scholars, such as Aristotle, and yet we are still allowing the rich and powerful not only to dictate the nature of society we live in but also to impose conditions that make it seem as if there is no alternative to the dominance of a system in which the interests of the rich have primacy over social needs.

In this context, the political system known as representative democracy has fallen completely into the hands of a moneyed oligarchy which controls humanity’s future. Democracy no longer exists in any meaningful sense. The main function of the citizenry in so-called “democratic” societies is to elect periodically the officials who are going to manage a system designed to serve the interests of a plutocracy and of global capitalism. The “common good” is dead, and in its place we have atomized, segmented societies in which the weak, the poor and powerless are left at the mercy of the gods.

The above features capture rather accurately, in my view, the socio-economic landscape and political culture of “late capitalism.” Nonetheless, the prospects for radical social change do not appear highly promising. Darkening times, strangely enough, have never favored the Left. And today’s Left appears preoccupied with identity politics and culture, while unified ideological gestalts guiding social and political action towards the building of a new socio-economic social order are sorely missing. What we may see then emerge in the years ahead is an even harsher and more authoritarian form of capitalism.

Then, there is the global warming phenomenon, which threatens to lead to the collapse of much of civilized life if it continues unabated. The extent to which the contemporary world is capable of addressing the effects of the climate crisis— heatwaves, frequent wildfires, longer periods of drought, rising sea levels, waves of mass migration — is indeed very much in doubt. Moreover, it is also unclear if a transition to clean energy sources, which is slow to emerge, even suffices at this point in order to contain the further rising of temperatures. To be sure, the global climate crisis will produce in the not-too-distant future major economic disasters, social upheavals and political instability.

If the climate change crisis is not enough to make one convinced that we live in ominously dangerous times, add to the above picture the ever-present threat of nuclear weapons. In fact, the threat of a nuclear war or the possibility of nuclear attacks is probably more pronounced in today’s global environment than any other time since the dawn of the atomic age. A multi-polar world with nuclear weapons is a far more unstable environment than a bipolar world with nuclear weapons, particularly if we take into account the growing presence and influence of non-state actors, such as extreme terrorist organizations, and the spread of irrational and/or fundamentalist thinking, which has emerged as the new plague in many countries around the world, including first and foremost the United States.

The above reflections are not intended to cause despair, or even to suggest that there hasn’t been improvement on some fronts, but only to show that human progress is not linear and that societal regression can easily take place under a socio-economic order designed to enhance the power of a few at the expense of society as a whole, which is indeed the trademark of neoliberal capitalism. Nations rise and fall, and even our ability to use reason does not necessarily increase with time and with the further advance of science.

As a matter of fact, a good argument can be made that we live today in a new age of unreason.

Science is still rejected by many people, objectivity and truth have become contested terms, and we are delaying the end of the fossil fuel age because we are accustomed to doing things in a particular way. Economics, politics, and psychology are all at work behind humanity’s apparent inability or unwillingness to alter course with regard to energy production and consumption even though we know that fossil fuels are destroying the environment by producing large amounts of greenhouse gases which trap hear and raise temperature across the globe.

Of course, capitalism itself is a highly irrational system for meeting human needs and wants; yet it’s been around for more than 500 years and predictions of a post-capitalist future knocking on our door should be taken with a grain of salt. Capitalism has demonstrated an uncanny ability to evolve, and can easily co-exist with different types of regimes, ranging from social-democracy to dictatorship. But now it is ruining the Earth, and unless we can this irrational economic system and, above all else, do away with its addiction to fossil fuels, the collapse of civilized social order is a near certainty. Then the floodgates of barbarism will be wide open.

–

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, climate change, the political economy of the United States, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He has published scores of books, and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Arabic, Croatian, Dutch, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthout and collected by Haymarket Books; Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors); and The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthout and collected by Haymarket Books (scheduled for publication in June 2021).

De rode loper naar Peking

‘Harde acties, die kunnen verschillen van het opsluiten van een directeur van een bedrijf, het bezetten van een fabriek, om het kapitalistische systeem in desorganisatie te brengen. Dat zou ook kunnen door sabotage bij belangrijke bedrijfsafdelingen, denk aan Philips.’ – Willem Oskam, televisie-interview

‘Harde acties, die kunnen verschillen van het opsluiten van een directeur van een bedrijf, het bezetten van een fabriek, om het kapitalistische systeem in desorganisatie te brengen. Dat zou ook kunnen door sabotage bij belangrijke bedrijfsafdelingen, denk aan Philips.’ – Willem Oskam, televisie-interview

Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, jaren negentig

De Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal in Amsterdam, begin jaren negentig. Achter de kassa van Modern Antikwariaat Van Gennep staat een norse man met het postuur van de Dokwerker.

Zijn enige politieke activiteit is nog het afrekenen van verramsjte boektitels over China, de Sovjet-Unie en van marxistische denkers als Antonio Gramsci en Alexandra Kollontai. Ooit was hij letterlijk en figuurlijk als voorzitter het boegbeeld van de Rode Jeugd, de revolutionaire jongerenorganisatie die in de tweede helft van de jaren zestig en begin jaren zeventig aan de stoelpoten van de gevestigde orde in Nederland knaagde. Willem Oskam heet hij, bijgenaamd Rooie Willem, of Dikke Willem. Zijn politieke activiteiten heeft hij achter zich gelaten en ingeruild voor een fervent supporterschap voor Ajax.

Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, 14 juni 1966

Amsterdam, de Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, 14 juni 1966. Een dag eerder is in Amsterdam het Bouwvakkersoproer uitgebroken. Bouwvakker Weggelaar sterft tijdens een demonstratie.

Getroffen door een steen, gegooid uit eigen gelederen, zo meldt De Telegraaf. Vanwege deze – onjuiste – berichtgeving proberen woedende bouwvakkers de volgende dag met emmers zand het gebouw van de krant binnen te dringen. Het zand moet in de persen, het drukken van de krant moet gestopt worden. Een vrachtauto en rollen krantenpapier worden in brand gestoken. Op dat moment rijdt Willem Oskam in het busje van zijn baas over de Nieuwezijds.

Hij parkeert het busje langs de kant en dringt te midden van bouwvakkers het gebouw binnen. Telegraafmedewerkers proberen de bouwvakkers tegen te houden. Ver komen de mannen niet, de persen zijn onbereikbaar. Wanneer Oskam later die dag het busje aflevert bij zijn baas, krijgt hij te horen dat hij de volgende dag niet meer terug hoeft te komen.

Havenarbeider

Willem Oskam (1943-2000) was de zoon van een havenarbeider uit een communistisch nest. Zijn vader was lid van de communistisch georiënteerde Eenheids Vakcentrale. Thuis werd trouw De Waarheid gelezen. Zijn jeugd offerde hij naar eigen zeggen op aan zijn ideaal: het communisme.

Oskam vertelde later dat hij tijdens zijn fanatieke, revolutionaire jaren iets weg had van een Jehova’s Getuige. Ook tijdens zijn meest fanatieke jaren woonde hij bij zijn ouders op zolder en voor ‘lonende relaties met het andere geslacht’ had hij simpelweg geen tijd. Hij werkte in Amsterdam als havenarbeider, als chauffeur en later op het Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis (IISG). Hij was actief in de CPN en maakte propaganda voor het communisme. Hij zorgde dat hij politiek geschoold werd door de werken van Lenin, Stalin en Mao Zedong te lezen en bouwde zo een indrukwekkende kennis over het marxistisch- leninistisch gedachtegoed op.

Spruitjeslucht

Tot diep in de jaren vijftig was Nederland een betrekkelijk ouderwets land. Men bleef over het algemeen trouw aan de tradities en gewoonten die al voor de Tweede Wereldoorlog hadden gegolden. Hoge geboortecijfers en frequent kerkbezoek werden in stand gehouden door de gevestigde katholieke en protestantse zuilen. De lonen waren relatief laag, arbeidsonrust was er nauwelijks en van emancipatie hadden nog weinigen gehoord. Weinig vrouwen werkten buitenshuis. De vaderlandse politiek leek zich tijdens de wederopbouw grotendeels volgens het vooroorlogse stramien te herstellen. In de jaren zestig echter ontstonden maatschappelijke en politieke bewegingen die zich wilden ontdoen van de benauwende spruitjeslucht en het maatschappelijke patroon van de jaren vijftig. Hoewel betere onderwijskansen, zorg en ouderdomsvoorzieningen voor iedereen een zorgeloze toekomst beloofden, bleken vooral jongeren zich niet altijd meer te kunnen vinden in de voorgespiegelde toekomst met een huis, gezin, werk, auto en televisie. Het vooruitzicht een leven te leven net als je ouders, met ingebakken omgangsvormen – een eentonig en gezapig bestaan – leek velen toch niet zo aanlokkelijk.

Verzet

Halverwege de jaren vijftig bood de rock-‘n-roll zulke jongeren een uitlaatklep. Door te genieten van andere muziek dan waar je ouders naar luisterden, ontstond de mogelijkheid je af te zetten tegen de leefwijze en opvattingen van ouders en andere opvoeders. Een andere haardracht en andere kleren onderstreepten dat gevoel. In de jaren zestig werkte de popmuziek als een soort slinger om het aanwakkerende verzet tegen de opvattingen van ouders, leraren, gezagsdragers, dominees en priesters, te verwoorden.

Mede onder invloed van de Koude Oorlogsdreiging en de oorlog in Vietnam ontstond in de jaren zestig onder jongeren het streven naar een andere inrichting van de samenleving. Het was vooral de beweging Provo die uiting wist te geven aan het groeiende besef dat de samenleving fundamenteel anders ingericht moest worden.