ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Situational Constraints On Argumentation In The Context Of Takeover Proposals.

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The 2010 ISSA conference has proposed for the first time a panel session devoted to financial argumentation. This is an indication that argumentation scholars are exploring an increasing variety of social domains (cf. van Eemeren 2010; Rigotti & Greco Morasso 2009b), in which people make use of arguments in order to handle with differences of opinion, interpersonal conflicts and individual and collective decision-making. The relevance of argumentation for finance is mainly due to the numerous decisions that investors and companies are concerned with. The inescapable and high uncertainty surrounding financial activities makes reasoning and argumentation fundamental and particularly complex, because the data (information) from which decisions must be inferentially drawn are often incomplete or not fully reliable (cf. Grinblatt & Titman 1998). In particular, financial argumentation is significantly conditioned by the information asymmetry and conflicts of interest that constrain the relationship between corporate managers/directors and shareholders (cf. Healy & Palepu 2001). These aspects typically characterizing financial interactions make financial communication particularly interesting for argumentation scholars. In fact, as a result of agency conflicts, shareholders could question managers’ willingness and ability to undertake value-creating business projects, and could thus cast doubt on the actual expediency of investing in the company; due to information asymmetry, investors may lack important premises to argumentatively support their own decisions and to critically assess managers’ decisions. It is not by chance that corporate financial communication not only consists in the disclosure of relevant information that investors need in order to reason out their decisions and assess the behavior of managers/directors: companies often defend argumentatively their decisions and try to justify the investments and transactions that they propose.

This paper shows this by focusing on the argumentative interactions entailed in takeover proposals – or takeover bids – (see also Green et al. 2008; Olson 2009; Palmieri 2008a&b), which constitute one of the most relevant activities of the financial market. In a takeover bid, one company – the bidder – proposes to the shareholders of another company – the target – to sell their shares in exchange for cash or bidder’s shares (cf. Ross et al. 2003). The directors of the target company, who may either endorse or oppose the bid, should publish a document in which their opinion is expressed and argumentatively based (cf. Easterbrook & Fishel 1981; Sudarsanam 1995; Haan-Kamminga 2006). Indeed, because shareholders are less informed and often less skilled than corporate directors, the quality of their decision-making largely depends on how the proposal is communicated, in particular which information bidder and target directors make available and which reasons they give to justify their position.

When target directors recommend shareholders to accept a takeover proposal, the offer is called friendly, while a bid that directors recommend to reject is called hostile. In hostile offers, bidder and target directors advance two opposite standpoints, thus making shareholders’ decision even more dilemmatic (cf. Brennan et al. 2010). In this paper I compare friendly and hostile bids made to companies listed in the UK stock market, to show how the two different argumentative situations (van Eemeren 2010) entail different strategic maneuvers that bidder and target directors activate in order to bring the eventual decision towards the desired outcome.

2. The communicative interactions implied by takeover bids

Through a takeover bid, the bidder aims to obtain the control over the target so that the two companies can be combined through merger or acquisition. The bid coincides with a public proposal made to target shareholders, i.e. those people who have invested in the company by buying shares. The ownership of listed companies is dispersed across hundreds of investors so that it is practically impossible to negotiate a deal with each of them individually. Thus the bid represents an instrument with which to reach all shareholders and seek their approval. If shareholders accept the offer and sell their shares, the control over the target is transferred to the bidder. The new board and executive team assume the delicate task of integrating the two businesses in order to realize the benefits expected at the outset.

The public offer is often preceded by negotiations involving both firms’ managers and directors (cf. Bruner 2004; Duhaime & Schwenk 1985). It goes without saying that, in case of agreement in the pre-offer phase, the bid will be friendly. Similarly, a bid which follows unsuccessful negotiations will be hostile. Pre-offer negotiations, however, are not necessary, as the bidder may immediately and directly address target shareholders. In this case, the bid is named unsolicited and its friendly/hostile mood (Morck et al. 1988) depends on whether the target board recommends acceptance or rejection of the offer.

From an argumentative viewpoint, the bidder necessarily holds the standpoint that accepting the offer would be expedient for target shareholders. We could consider it a virtual standpoint (van Eemeren et al. 1993: 104-105), entailed by the felicity conditions of the speech act “to propose” (cf. Colombetti 2001): by making a proposal, the speaker is committed to the claim (i.e. the standpoint) that the proposed action is expedient for the hearer. Of course, a proposal might be insincere. In this case, the speaker proposes something that he/she actually believes it is expedient only for him/herself, though the opposite belief is externalized.

It is not by chance that “pro-shareholders” and “pro-managers/directors” reasons are distinguished within the impressive literature in financial economics which discusses the motives behind takeover bids (cf. Trautwein 1990; Shleifer & Vishny 1991; Berkovitch & Narayanan 1993; Andrade et al. 2001). In fact, managers/directors should, in line with their institutional commitments, pursue a takeover only if this is expected to benefit the company and, in particular, its shareholders. However, because of agency problems, their decision to acquire another company might be due only to motives of personal benefit, such as power, prestige, etc. (cf. Amihud & Lev 1981; Morck et al. 1990). A takeover bid benefits bidder shareholders if the implied acquisition increases the value of their shares. This can occur because the combination produces synergies, i.e. additional value which could not be created without the acquisition (cf. Damodaran 2005: 3). The possibility to obtain synergies allows the bidder to pay a premium (i.e. a price above the value of the target), which coincides with target shareholders’ gain and constitutes the main rationale for tendering their shares. Obviously, it might also be the case that the bidder pays an excessively high price (i.e. a price including a premium which cannot be recovered by the synergies produced by the acquisition), so that only target shareholders will gain (cf. Roll 1986). However, it is also possible that the bidder decides to acquire a company because the latter is undervalued by the stock market (cf. Shleifer & Vishny 2003). In this case, the bidder and its shareholders would gain while target shareholders would lose.

Instead, the speech act performed by the target board corresponds to an advice (recommendation), in which an entailment of benevolence is certainly involved, but the propositional content can refer either to the acceptance of the offer or to its rejection. In fact, the board is not proposing a deal, but, in relation to a proposed action, is recommending the best course of action to the decision-maker. If directors recommend the acceptance of the offer, they are committed to the virtual standpoint that this is expedient for target shareholders; otherwise, their implicit claim is that rejecting the offer would be desirable.

Numerous studies have also been devoted to the motives behind target directors’ recommendation to shareholders (Easterbrook & Fischel 1981; Walkling & Long 1984; Sudarsanam 1995; Rhodes-Kropf & Viswanathan 2004). Similarly in this case, motives coinciding with the fulfillment of the institutional commitments towards shareholders (the shareholders-welfare hypothesis) are distinguished from decisions affected by agency problems (the management-welfare hypothesis). In particular, it is suggested that target managers and directors could be concerned with the implications of the acquisition on their job position rather than with maximizing shareholder value.

Now, since target shareholders are less informed than managers and directors (asymmetric information), they often lack the premises for determining whether an offer is expedient, whether the bidder is paying an adequate price, whether the board’s recommendation is credible, etc.

In order to empower target shareholders’ decision-making, strict takeover rules exist in all developed financial systems, imposing communicative (disclosure) and non-communicative commitments on companies. In my analysis I focus specifically on bids addressed to companies listed on the UK stock market, as it is the Europe’s most active takeover market. In the UK, takeover bids are subject to the City Code on Takeovers and Mergers, which implements the European Directive on Takeover Bids (cf. Haan-Kamminga 2006).

The City Code represents a framework for conducting the bid, establishing, in particular, the kind of information that must be disclosed, who and when should disclose such information, and defining appropriate standards of care when publishing a document. In fact, echoing the European Directive, the City Code states that “shareholders must be given sufficient information and advice to enable them to reach a properly informed decision as to the merits or demerits of an offer” (Rule 23).

As one of its purposes is to avoid inequalities of information among investors (see General Principle 1 and Rule 20. Equality of information), the Code emphasizes the importance of absolute secrecy before any public announcement is made (Rule 2.1) and requires an announcement to be made in any case when rumors and speculation emerge (Rules 2.2; 2.5).

Once a statement is published, the offer period begins, during which the companies concerned are subject to the commitments imposed by the Code. An important distinction must be drawn between the announcement of a possible offer (Rule 2.4) and that involving a firm intention to make an offer (henceforth, firm intention announcement) (Rule 2.5). The former, usually made by the potential target, does not pre-commit the potential bidder; instead, the firm intention announcement, unless special circumstances materialize, must be followed by the offer, which is formally made with the publication of the offer document.

The bidder must cover numerous points in the offer document, including the financial terms of the offer and the consequences of the implied combination for the target company, its management and employees. The Code recognizes in this way that the takeover bid is more than a trading of securities, as it brings about a corporate combination which might significantly affect the target company and its stakeholders. Furthermore, a burden of proof is imposed, as the long-term commercial justification of the offer should be stated (Rule 24).

After the offer document has been issued, the Code requests target directors to advise target shareholders by publishing a document in which the directors express an opinion about the offer and state the reasons for forming such an opinion (Rule 25).

Therefore, two fundamental interactions occur during the offer period: one between the bidding company and the target shareholders, in which the former makes an offer to the latter; the other between target directors and shareholders, in which the former gives advice to the latter. Both interactions envisage argumentation, as the Code requests the bidder to motivate the offer from a commercial viewpoint and the target board to argumentatively support its opinion.

3. Comparing argumentation in friendly and hostile offers

The friendly/hostile distinction is particularly relevant when we consider these two interactions from the argumentative point of view, in relation to the issue p:”should target shareholders accept the offer?”. In fact, a friendly offer entails the bidder and the target boards of directors holding the same positive standpoint +/p: “target shareholders should accept the offer”; instead, a hostile offer brings a different confrontational trigger (cf. van Eemeren & Garssen 2008:12): the bidder virtually holds the previously indicated positive standpoint (+/p), while the target board, by recommending the rejection of the offer, has to defend the opposite standpoint –/p: “LSE shareholders should not accept (reject) NASDAQ’s offer”. Notably, in relation to this issue, the City Code only imposes a burden of proof on the target board.

As the (in-)expediency of an offer is far from being immediately evident, shareholders will at least cast doubt on these standpoints. Thus, in both friendly and hostile offers, target shareholders assume the role of antagonist within an argumentative discussion (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, 2004), which envisages two different initial situations within the two types of offer.

In order to compare how the two different situations are argumentatively dealt with, I have considered several cases of UK takeover bids made in the 2006-2010 period . In this paper I will focus on two prototypical cases: the friendly bid made by BAE Systems to Detica (July 2008) and the hostile bid that NASDAQ made to the London Stock Exchange (December 2006). Both offers were in cash. The first one was accepted, while the second one was rejected by shareholders.

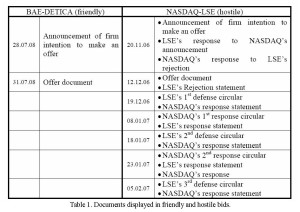

An important difference between friendly and hostile cases emerges already when we consider the relevant texts published during the offer period. As Table 1 shows, the crucial communicative events in the friendly case (the acquisition of Detica by BAE Systems) consist of two documents: the firm intention announcement and the offer document. Moreover, an inspection of these two texts reveals that the content of the offer document is largely anticipated in the announcement (cf. Palmieri 2010).

The reason why the friendly case does not include a document specifically devoted to the target directors’ reasoned opinion is that the latter is included into the bidder’s documents (see later).

The hostile case is evidently more complex, since the views of the bidder and the target directors are communicated separately: the firm intention announcement is immediately followed by the statement from the target, while the offer document is – so to say – replied to by the defense circular, through which the target board attempts to persuade shareholders to reject the offer by argumentatively justifying its position. Moreover, further response statements are published, by means of new announcements (press releases) or circulars to shareholders. As Haan-Kamminga (2006) suggests, hostile bids entail a battle between the two boards, which can be fought at three levels: (1) a financial battle, in which the target board tries to make use of various anti-takeover measures, which regulations try to prevent as much as possible; (2) a legal battle, in which the companies litigate in a court; (3) a communication (or media) battle. From Table 1, it can be seen that a communication battle has been fought by the London Stock Exchange (LSE) and NASDAQ.

The two different situations can be seen from the beginning of the offer period. In fact, friendly offers typically begin with a joint announcement:

1. The boards of directors of BAE Systems and Detica announce that they have reached agreement on the terms of a recommended cash offer to acquire the whole of the issued and to be issued share capital of Detica (BAE-Detica, firm intention announcement, 28.VII.2008).

From this statement we infer that the public offer was preceded by a successful negotiation involving managers and directors, in which, presumably, argumentation was relevantly involved as is typically the case in negotiation dialogues (cf. Walton & Krabbe 1998).

In the hostile case, two distinct press releases were issued: NASDAQ individually announced its intention to make an offer (ex. 2), then the LSE board reacted on the same day by publishing its own announcement (ex. 3):

2. The Board of NASDAQ announces the terms of Final Offers to be made by NAL, a wholly owned subsidiary of NASDAQ, for the entire issued and to be issued share capital of LSE. (NASDAQ, firm intention announcement, 20.XI.2006).

3. The Board of London Stock Exchange Group plc (the “Company”) rejects Nasdaq’s final offer to acquire the Company for 1243p per share in cash. The Board firmly believes that the proposal, which represents only a 2 per cent premium to the market price at the close of business on 17 November 2006, substantially undervalues the Company and fails to reflect its unique strategic position and the powerful earnings and operational momentum of the business. (LSE, Statement re: Nasdaq final offer, 20.XI.2006).

3.1. The argumentative coordination in friendly bids

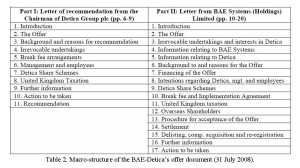

As Table 2 shows, the offer document is divided in two parts, the first being the letter of recommendation from the target board and the second being the letter from the bidder representing the formal offer. Most of the paragraphs of the target letter (e.g. “the offer”, “irrevocable undertakings”, “United Kingdom Taxation”, etc.) actually coincide with those contained in the bidder’s, as the former reports the same text of the latter and explicitly refers to it (through expressions such as “as stated in BAE’s letter”; “Your attention is drawn to the letter from BAE Systems Holdings on pages 10 to 20”).

Two paragraphs immediately capture the attention of the argumentation analyst: “Background and reasons for the offer”, located in the bidder’s letter (par. 6) and “Background and reasons for the recommendation”, located in the target’s letter (par. 3).

The first one focuses on the reasonableness of the acquisition, as the reasons that led to the decision of pursuing the offer are exposed:

1. 4. Background to and reasons for the Offer

BAE Systems has identified the national security and resilience (NS&R) sector as an evolving and growing sector benefiting from increasing priority government attention. A strategic objective of BAE Systems is to establish security businesses in its home markets. While BAE Systems has been developing plans for substantial organic investment to pursue growth NS&R opportunities in these markets, the proposed acquisition of Detica provides an economically attractive and accelerated implementation of its strategy to address these opportunities.

[…] The combination of Detica’s well established customer relationships and technical capabilities together with BAE Systems’ system integration capabilities will result in a depth of financial and technical capability to address growth opportunities and better serve customers in the NS&R sector.

[…] BAE Systems’ existing activities and structure will provide a platform for Detica to apply its capabilities into the US Homeland Security market.

The business combination is expected to benefit from strong growth, consistent with the anticipated growth in the sector, and from cost synergies including benefits from more efficient internal investment. BAE Systems believes these benefits will enable the acquisition to achieve a return in excess of BAE Systems’ cost of capital in the third full-year following completion. (BAE-Detica, offer document, p.12, 31.VII. 2008)

The acquisition is seen as subservient in realizing a “strategic objective of BAE”, in line with an identified business opportunity (lines 2-3). In particular, the acquisition is expected to efficiently improve BAE’s means for realizing its goals (lines 7-9). The integration of the two companies’ respective strengths is emphasized and the benefits that BAE would bring to Detica are also indicated (lines 14-15). The bidder expresses its belief that the acquisition will produce a superior (bidder) shareholder return (lines 18-21).

Through all this information, the writer activates a pragmatic argumentation (Walton 1990, Rigotti 2008), in which the conditions for a happy joint action are made explicit: the realization of a goal benefiting both agents, the compatibility and integration of their respective means and even their improvement (cf. Rigotti & Palmieri 2010) .

The issue tackled in this paragraph concerns the expediency of the combination implied by the offer for the two companies involved and not the financial attractiveness of the offer for target shareholders. As BAE’s bid was in cash, meaning that Detica shareholders would cease to invest in the company, one could be tempted to conclude that these arguments developed by the bidder are actually addressed to bidder shareholders and to the stakeholders that would be affected by the combination. Without overlooking the presence of a multiple audience during the offer period (notably in this respect, the City Code requests the offer document and the target board’s opinion to also be sent to employees), I argue that there are two aspects that make the content of this paragraph relevant to the decision that target shareholders should make. Firstly, shareholders, as owners of the company, could also be concerned with the social and organizational implications that would occur in case of acceptance of the offer. Indeed, this is probably in the spirit of takeover rules, which request that shareholders receive information about the after-deal company. Secondly, as mentioned previously, a premium in the offer price can only be justified if the implied combination produces a value superior to such a premium. Otherwise, either the price is excessively high or the bidder is attempting to buy an undervalued company. In the latter case, target shareholders would probably reject the offer. Following this interpretation, the bidder should dispel suspicions of undervaluation by convincing target shareholders that the proposed corporate acquisition makes sense from a financial viewpoint.

That said, we remark that neither Detica shareholders nor the bid itself are explicitly mentioned in the paragraph. In other words, the financial attractiveness of the offer is not directly discussed, as the focus is rather the possible acquisition that would follow the offer.

Indeed, the reasons why Detica shareholders should accept the bid are given by Detica directors in a specific paragraph of their recommendation letter:

1. 5. Background to and reasons for the recommendation

Detica’s business strategy has been to become the pre-eminent consulting provider servicing the counter-threat agenda in both the UK and the US. […]

As a result of its success in executing this strategy, the Detica Group has delivered compound annual growth of 39 per cent and 25 per cent in revenues and adjusted diluted earnings per share, respectively, over the five year period ended 31 March 2008. This growth in the business has been predominantly organic, supplemented by acquisitions including, most recently, those of DFI in 2007 and m.a.partners in 2006.

Current Trading and Outlook

The current financial year has started well with the Detica Group performing in line with the Board’s expectations. […] Detica’s UK Government business continues to perform very well […] As a result, the outlook for the Detica Group remains good and the Board’s expectations for the current financial year remain unchanged.

The Offer

Notwithstanding the Directors’ confidence in the prospects for the Detica Group, the approach by BAE Systems and level of the Offer is such that the Directors believe it provides Detica Shareholders with certainty of value at an attractive level, which reflects both the quality of the Detica business and its standing in its markets, and that Detica Shareholders should have the opportunity to realise their investment in Detica. In addition, the Directors also recognise the benefits and enhanced opportunities available to Detica and its employees as part of the enlarged group since it will have increased resources to compete more fully and will benefit from the significant international footprint that BAE Systems will bring.

The Offer represents a premium of approximately 57 per cent to the Detica closing price of 281 pence on 17 July 2008, being the last business day prior to the announcement by Detica that it had received a preliminary approach which may or may not lead to an offer being made for Detica; approximately 66 per cent. to the volume weighted average closing price of approximately 265 pence per Detica share for the one month period to 17 July 2008; and approximately 70 per cent to the volume weighted average closing price of approximately 259 pence per Detica share for the six month period to 17 July 2008. (BAE-Detica, offer document, p. 7, 31.VII.2008)

In the first part, the board stresses the high growth achieved both organically (i.e. by implementing its business strategy) and inorganically (i.e. by small acquisitions). Then, the good prospects for the near future are confirmed. Such a very positive outlook is however offset by the value of BAE’s offer. A “notwithstanding” indicates precisely that the good past and future performances of the company are not sufficient to reject the proposal in the given terms.

Based on the principle that “Detica Shareholders should have the opportunity to realise their investment in Detica” and on the presumed fact that the offer provides an attractive and certain value, the directors implicitly conclude that accepting the bid is preferable than continuing to invest in Detica as a standalone company.

The argument from alternatives is exploited here: “given two mutually exclusive actions – X and Y – if X is better than Y, X should be chosen”. What makes tendering a better alternative is, according to Detica directors, that BAE’s offer is in cash, which provides certainty, and that the price is very high. The latter aspect becomes a sub-standpoint that is justified through a comparison between the offer price and the pre-offer market price, which would demonstrate that a premium is included in the bid. More precisely, three different values are computed which, according to the reference day that is chosen, imply different levels of premium (lines 29-37).

This argumentation presupposes a general opinion (endoxon, see Rigotti 2008) that market prices are reliable indicators of Detica’s value. Such an endoxon is combined with more specific data concerning the share price of Detica before the offer, whose computations are actually taken from the paragraph indicating the terms of the offer (“The offer”), which appears both in the bidder’s letter and in the target’s letter (see Table 2). Through the model of critical discussion (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004) we can reconstruct an opening stage, in which the Detica board assumes the burden of proving that the offer price is attractive and establishes the just mentioned endoxon and data. In the argumentation stage, these material starting points become the premises which, once conjoined, activate an inferential connection (cf. Rigotti & Greco Morasso 2010) which allows directors to conclude that the offer is financially attractive.

Therefore, in friendly bids, the task of argumentatively defending the expediency of the offer in front of target shareholders is mainly accomplished by the target board. The bidder focuses on the justification for the implied acquisition (whose possible relevance for target shareholders has already been explained) and, remarkably, does not make its virtual standpoint explicit. Instead, the bidder seems to rely on the target directors’ recommendation, which is explicitly referred to at the beginning of its letter:

6. Your attention is drawn to the letter of recommendation from the Chairman of Detica in Part I of this document, which sets out the reasons why the Detica Directors […] consider the terms of the Offer to be fair and reasonable and unanimously recommend that all Detica Shareholders accept the Offer. (BAE-Detica, offer document, p.1, 31.VII.2008)

In other words, a distribution of tasks emerges between the two boards: the justification of the acquisition is a task entrusted to the bidder while the reasons for preferring to tender are developed by the target.

This distribution of tasks shows respect for each other’s province and institutional role, which gives a better position to know. In particular, the assessment of the two alternatives (to sell or to continue investing) requires a valuation of the target’s standalone prospects, which target managers and directors are in the best position to make. This argumentative coordination reflects the nature of the deal as a negotiated transaction between the two management teams, which in turn led to a friendly offer. It seems that the bidder has devoted all its argumentative efforts to convincing target managers/directors to endorse the bid. Once this consent has been obtained, the bidder addresses target shareholders but refrains from advancing its main standpoint, namely that shareholders should accept the offer, and from argumentatively supporting such claim.

3.2. The argumentative battle in hostile offers

A substantially different scenario occurred in the NASDAQ-LSE case, as can be deduced from Table 1. Pre-offer negotiations have been unsuccessful and the coordination of the two sides’ positions is absent: NASDAQ’s firm intention announcement does not include LSE’s reasoned opinion and the offer document does not contain a letter from the LSE board.

The bidder’s argumentative strategy is clearly affected by the T-directors’ rejection. In the offer document, the bidder still defends the reasonableness of the implied combination:

7. Reasons for the Final Offers

[…] The combination of NASDAQ and LSE will bring together two of the world’s leading groups in the global exchange sector to the benefit of their respective users and the wider global financial community […] (NASDAQ, offer document, 12.XII.2006)

However, unlike that found in friendly offers, the “hostile” bidder also argues in favor of the offer acceptance as these two examples show (the second referring to the hostile bid made by Centrica to Venture) :

8. An attractive offer which fully reflects both LSE’s standalone prospects and an appropriate premium […]. An offer price of 1,243 pence per LSE Ordinary Share represents:

• a 54 per cent. premium over the Closing Price on 10 March 2006, the Business Day immediately prior to LSE’s announcement that it had received a pre-conditional approach from NASDAQ, as adjusted […]

• a 40 per cent. premium to NASDAQ’s indicative offer price of 9 March 2006, as adjusted for the LSE Capital Return;

• a 2 per cent. premium over the Closing Price on 17 November 2006, the Business Day immediately prior to the date of the announcement of the Final Offers (NASDAQ, firm intention announcement, 20.XI.2006)

9. Centrica believes that the Offer represents a compelling opportunity for Venture Shareholders to realise the value of their Venture Shares in cash at a significant premium to Venture’s pre-bid speculation share price and at a time of continuing economic uncertainty and market volatility. (Centrica, firm intention announcement, 10.VII.2009)

If we compare these two examples with example (5) we find numerous similarities, in particular the focus put on the certainty provided by the offer and the attractive value of the bid computed by relying on the pre-offer share prices.The fundamental difference is that, in BAE’s bid, these arguments are developed by the directors of the target (Detica), while in NASDAQ and Centrica’s bids, the bidder put them forward after having advanced its standpoint. Thus, an evident attempt to replace the target directors in their advisory function has evidently been made, which seems to be a prelude to the institutional replacement that typically occurs after a hostile takeover succeeds.The reaction of the target directors can be seen in Table 1: the LSE Board makes use of a special text typology, the takeover defense circular, which is exclusively adopted for unfriendly proposals. It is a document of about 20 pages, combining written text, figures, graphs etc. The defense circular is characterized by an explicitly argumentative intention. The standpoint is already declared on the cover page, where it is spelled out as a directive speech act (e.g. “Reject NASDAQ’s offer”). In the letter introducing the document, the board also assumes the burden of proof (typically with a sentence like “in this document we explain why we believe that you should reject the offer”).For reasons of space, I shall focus on one specific aspect, namely the value of the price offered, which represents a crucial issue in hostile bids. While the bidder defends the attractiveness of the offer price on the basis of pre-offer share prices (as the target board does in friendly bids), the target relies on alternative methods. Implicitly, the endoxon stating that market prices are reliable indicators of value is questioned, so that another kind of data must be invoked (in the opening stage) in order to determine the standalone value of the target and to infer (in the argumentation stage) the expediency or not of the offer.The method used by the LSE board is based on a particular form of analogy argument, in which the value of LSE is estimated through a relative valuation based on the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E) of comparable companies.

10. Standalone value is not being recognized<

Nasdaq’s offer of 1,243 pence per ordinary share represents a multiple of 24.7 times the Exchange’s forecast adjusted basic EPS for the 12 months to 31 December 2006. This values your company below the trading multiples of virtually all other major listed exchanges.[graph comparing the P/E ratio of numerous other exchanges](LSE, defense circular, p. 9, 19.XII.2006)The rationale behind the use of earnings multiples is based on the assumption that the relation between stock price and earnings (P/E ratio) should be the same for companies sharing some essential characteristics, in particular growth, risk and cash flows (cf. Damodaran 2005). Therefore, by applying the P/E of such similar companies to the earnings of LSE, we obtain an estimate of the LSE price.Thus, at this point the crucial issue is to establish the set of similar companies (peer group). In fact, by considering or excluding some firms in the peer group, the eventual result might differ significantly. It is not by chance that, in its response document, NASDAQ criticizes the choice made by LSE:

11. The analysis in the LSE Defence Document is based on 2006 P/E multiples for many different types of exchanges from all over the world. […] we question why a cash equities exchange chooses to compare itself with businesses as diverse as a commodity futures exchange, a derivatives and physical energy marketplace and an electronic derivatives and options exchange. (NASDAQ’s response, 8.I.2007)

Having refuted the endoxon on which the LSE’s value case was based, NASDAQ selects the data which correspond to its own criterion of selection (cash equities exchange). In this way, a different value is obtained which would bring to conclude that the offer actually includes a premium.Interestingly, an intense discussion by distance now takes place, as LSE reacts again by giving further reasons – based this time on an appeal to expert opinion – why its value case was actually correct:

12. Nasdaq wrongly claims that the Exchange’s peer group is restricted to European exchanges. This is not the view of financial experts who have provided “fairness opinions” for recent precedent exchange transactions [a list of analysts’ opinions follows] (LSE, second defense circular, p. 14, 18.I.2007).

4. Conclusions

The analysis of friendly and hostile takeover proposals, which was discussed in this paper, allows comparison of argumentation in two different situations of the same type of social interaction.Friendly offers envisage a situation in which the two arguers have already found an agreement. This brings a coordinated public argumentation where the decision-making audience is addressed. Each side limits itself to tackling the sub-issue that its institutional position allows to deal with at best and for which the regulation has imposed a burden of proof. Thus, the proposal maker refrains from arguing in favor of its proposal, because this is already done by someone being in a better position to know.In hostile offers, the argumentative “rate” increases, as more texts are published and more specific arguments are advanced in support of the standpoint. This suggests that companies engaged in a takeover deal consider argumentation as a relevant instrument in realizing their objectives. An argumentative battle emerges in which each side seeks to impose its own analysis against the other’s one. In particular, the endoxa on which the other side bases its own argumentation are criticized in order to prevent some information from becoming the premises of arguments that would prove the opposite standpoint.More generally, it emerges that argumentation is extremely important in determining which information is relevant in financial decisions. The analysis of takeover bids clearly confirms that financial communication cannot be reduced to the disclosure of private information. Numerous data, being private or already public information, acquire or lose their relevance by being argumentatively elaborated.

NOTES

[i] In modern public corporations shareholders elect the Board of Directors who hire the executive managers and monitor them on behalf of shareholders. In practice, however, directors are more closely related to managers rather than shareholders. The Chief Executive Officer is usually also a member and sometimes even the Chairman of the Board of Directors. In any case, conflicts or disagreements between managers and directors are rarely externalized so that, from an argumentative viewpoint, they advance and defend the same standpoint in relation to an emerging issue. For this reason, in this paper managers and directors are not systematically distinguished, although they cover two different institutional positions.

[ii] In financial economics, the relationship between corporate managers/directors and shareholders has been typically interpreted in the framework of agency theory (Ross 1973; Jensen & Meckling 1976). An agency relationship arises when one person (the principal) engages another person (the agent) to perform a service on his/her behalf. This agreement, which in general entails a certain delegation of decision-making, is subject to several conflicts of interest, as the agent, if not properly incentivized, might be tempted to pursue his/her own goals instead of being fully committed to the interests of the principal.

[iii] From a legal point of view, in a merger one company is absorbed into the other and ceases to exist. Instead, the acquisition of the majority or all the shares brings the delisting of the acquired company, which becomes a subsidiary of the acquiring one. Economists as well as financial professionals usually adopt the terms merger, acquisition and takeover interchangeably, because the distinction is often relevant for law or accounting and less for the business and financial implications on the relevant stakeholders. On this point, see also Bruner (2004: p.1); Grinblatt & Titman (1998).

[iv] Sometimes, it also happens that an activist shareholder openly manifests disagreement with one of the advanced standpoints, even trying to persuade fellow shareholders to accept/reject the offer. For an example of such mixed discussions, see Palmieri (2008b).

[v] This research is based on my PhD dissertation (Palmieri 2010), in which ten cases of friendly bid and ten cases of hostile bid have been considered.

[vi] In my PhD dissertation I have shown that every paragraph of the BAE’s firm intention announcement (“The Offer”, “Irrevocable Undertakings”, “Information relating to BAE Systems”, “Information relating to Detica”, “Background to and reasons for the Offer”, “Background to and reasons for the recommendation”, “Recommendation”, “Financing of the Offer”, “Management and employees”, “Detica Share Schemes”, “Disclosure of interests in Detica relevant securities”, “Break Fee and Implementation Agreement”, “Delisting, compulsory acquisition and re-registration”) reappears in the offer document with the identical content.

[vii] Hostile takeovers are often disciplinary (cf. Grinblatt & Titman 1998, pp. 674-675): the bidder intends to remove existing target managers and gain from a better management of the firm’s assets.

[viii] In the cases considered in my PhD dissertation (Palmieri 2010), I found two different strategies adopted by target directors in order to prove the price’s inadequacy: relative valuation of the target standalone value, which is based on analogy reasoning, and asset revaluation made by an external valuer, which is based on an appeal to authority.

REFERENCES

Amihud, Y., & Lev, B. (1981). Risk reduction as a managerial motive for conglomerate mergers. Bell Journal of Economics, 12, 605-617.

Andrade, G., Mitchell, M., & Stafford E. (2001). New Evidence and Perspectives on Mergers. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 103-120.

Berkovitch, E., & Narayanan, M.P. (1993). Motives for Takeovers: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 28, 347-362.

Brennan, N.M., Daly, C., & Harrington, C. (2010). Rhetoric, Argument and Impression Management in Hostile Takeover Defence Documents. British Accounting Review, 42(4), 253-268.

Bruner, R.F. (2004). Applied Mergers and Acquisitions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Colombetti, M. (2001). A language for artificial agents. Studies in Communication Sciences, 1(1), 1-32.

Damodaran, A. (2005). The Dark Side of Valuation: Valuing Old Tech, New Tech, and New Economy Companies. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Halls.

Daniels, R.J. (1993). Stakeholders and Takeovers: Can Contractarianism be Compassionate? University of Toronto Law Journal, 43(3), 315-351.

Duhaime, I.M., & Schwenk, C.R. (1985). Conjectures on cognitive simplification in acquisition and divestment decision making. Academy of Management Review, 10, 287-295.

Easterbrook, F.H. & Fischel, D.R. (1981). The proper role of target’s management in responding to a tender offer. Harvard Law Review, 94, 1161-1204.

Eemeren, F.H. van (2010). Strategic Maneuvering in Argumentative Discourse. Extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Garssen, B.J. (2008). Controversy and confrontation in argumentative discourse. In F.H. van Eemeren B.J. & Garssen (Eds.), Controversy and confrontation (pp. 1-26). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies: A Pragma-Dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Grootendorst, R. Jackson, S., & Jacobs, S. (1993). Reconstructing Argumentative Discourse. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Green, S.E., Babb, M., & Alpaslan, C.M. (2008). Institutional Field Dynamics and the Competition Between Institutional Logics. The Role of Rhetoric in the Evolving Control of the Modern Corporation. Management Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 40-73.

Grinblatt, M., & Titman, S. (1998). Financial Markets and Corporate Strategy. Boston (MA): McGraw Hill.

Haan-Kamminga, A. (2006). Supervision on Takeover Bids: A Comparison of Regulatory Arrangements. Deventer: Kluwer.

Healy, P.M., & Palepu, K.G. (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31, 405-440.

Jensen, M., & Meckling W. H. (1976). Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360.

Morck, R., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R.W. (1988). Characteristics of Targets of Hostile and Friendly Takeovers. In A.J. Auerbach (Ed.), Corporate Takeovers: Causes and Consequences (pp. 101-136), Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Morck, R., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R.W. (1990). Do Managerial Objectives Drive Bad Acquisitions? The Journal of Finance, 45(1), 31-48.

Olson, K.M. (2009). Rethinking Loci Communes and Burkean Transcendence. Rhetorical Leadership While Contesting Change in the Takeover Struggle Between AirTran and Midwest Airlines. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 23(1), 28-60.

Palmieri, R. (2008a). Reconstructing argumentative interactions in M&A offers. Studies in Communication Sciences, 8(2), 279-302.

Palmieri, R. (2008b). Argumentative dialogues in Mergers & Acquisitions (M&As): evidence from investors and analysts conference calls. L’analisi Linguistica e Letteraria (special issue 2/2), 859-872.

Palmieri, R. (2010). The arguments of corporate directors in takeover bids. Comparing argumentative strategies in the context of friendly and hostile offers in the UK takeover market. PhD dissertation. Lugano: USI.

Rhodes-Kropf, M., & Viswanathan, S. (2004). Market Valuation and Merger Waves. The Journal of Finance, 59(6), 2685-2718.

Rigotti, E. (2008). Locus a causa finali. L’analisi Linguistica e Letteraria (special issue 2/2), 559-576.

Rigotti, E., & Greco Morasso, S. (2009a). Argumentation as an object of interest and as a social and cultural resource. In N. Muller-Mirza & A.N. Perret-Clermont (Eds), Argumentation and Education (pp. 9-66), New York: Springer.

Rigotti, E., & Greco Morasso, S. (2009b). Editorial & Guest Editors’ Introduction: Argumentative Processes and Communication Contexts. Studies in Communication Sciences, 9(2), 5-18.

Rigotti, E., & Palmieri, R. (2010). Analyzing and evaluating complex argumentation in an economic-financial context. In C. Reed & C.W. Tindale (Eds.), Dialectics, Dialogue And Argumentation. An Examination Of Douglas Walton’s Theories Of Reasoning (pp. 85-99), London: College.

Roll, R. (1986). The Hubris Hypothesis of Corporate Takeovers. The Journal of Business, 59(2), 197-216.

Ross, S.A. (1973). The Economic Theory of Agency: The Principal’s problem. The American Economic Review, 63(2), 134-139.

Ross, S.A., Westerfield, R.W., & Jaffe, J. (2003). Corporate Finance (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R.W. (1991). Takeovers in the ’60s and the ’80s: Evidence and Implications. Strategic Management Journal, 12(special Issue), 51-59.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R.W. (2003). Stock market driven acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, 70(3), 295-311.

Sudarsanam, P.S. (1995). The role of defensive strategies and ownership structure of target firms: evidence from UK hostile takeover bids. European Financial Management,1(3), 223-240.

Trautwein, F. (1990). Merger motives and merger prescriptions. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 283-295.

Walkling, R.A., & Long, M.S. (1984). Agency theory, managerial welfare, and takeover bid resistance. The Rand Journal of Economics, 15, 54-68.

Walton, D.N. (1990). Practical Reasoning: Goal-driven, Knowledge-based, Action-guiding Argumentation. Savage (Maryland): Rowman and Littlefield.

Walton, D.N., & Krabbe, E.C.W. (1995). Commitment in dialogue. Basic Concepts of Interpersonal Reasoning. Albany: State University of New York Press.