ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ Chinese Understanding Of Interpersonal Arguing: A Cross-Cultural Analysis

Abstract: China has a longstanding tradition of stressing the values of harmony and coherence, and Chinese society has always been alleged to be a group where conflict avoidance is viewed more positively than direct confrontation and argumentation. In order to evaluate the validity of this claim, this paper sketches Chinese people’s feelings and understandings of interpersonal arguing by reporting results of a data collection in China, using measures of argumentativeness, verbal aggressiveness, argument frames, and personalization of conflict. Chinese and U.S. data differed in complex ways, but did not show Chinese respondents to be more avoidant. The Chinese correlations among variables were a reasonable match to expectations based on Western argumentation theories. The paper offers evidence that Chinese respondents had a more sophisticated understanding of interpersonal arguing than their U.S. counterparts, and were more sensitive to the constructive possibilities of face-to-face disagreement.

Keywords: argument predispositions, China, confrontation, interpersonal arguing

1. Introduction: Chinese orientations to interpersonal arguing

Most of the existing literature on argumentation and communication studies suggests that the Chinese culture has long stressed the values of harmony, coherence, and holism, implying that Chinese people would prefer non-confrontational, non-argumentative, and conflict avoidance approaches over direct argumentation and confrontation in their social lives (Jensen, 1987, Leung, 1988; 1997; Lin, Zhao, & Zhao, 2010; Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003; Oetzel et al, 2001; Triandis, 1995). Accordingly, Chinese society has always been regarded as a group where conflict avoidance is viewed more positively than direct confrontation and argumentation, and Chinese people’s understanding of, and attitudes towards, interpersonal arguing have been supposed to differ significantly from those of Western people, whose culture has appreciated, from its very beginning, the importance of argumentative practices. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2014 – Denying The Antecedent Probabilized: A Dialectical View

Abstract: This article provides an analysis and evaluation for probabilistic version of arguments that deny the antecedent (DAp). Stressing the effects of premise retraction vs. premise subtraction in a dialectical setting, the cogency of DAp arguments is shown to depend on premises that normally remain implicit. The evaluation remains restricted to a Pascalian notion of probability, which is briefly compared to its Baconian variant. Moreover, DAp is presented as an exam-question plus evaluation that can be deployed as a learning assessment-instrument at graduate-level.

Keywords: affirming the consequent, delay tactic, denying the antecedent, dialectics, inductive logic, modus ponens, modus tollens, probabilistic independence, probabilistic relevance, retraction, subtraction

1. Introduction

We treat the evaluation of DAp, a probabilistic version of what classical logic correctly treats as the formal fallacy of denying the antecedent (DA), i.e., the deductively invalid attempt at inferring the conclusion ~c from the premises a->c and ~a, where a stands for antecedent, c for consequent, and ~ for negation. Examples include:

1. Had my client been at the crime scene (a), then he would probably be guilty (c). But he wasn’t (~a), so he probably isn’t (~c).

2. If the lights are on (a), then probably someone’s at home (c). But the lights are out (~a), so probably no one is (~c).

3. If the product sells (a), then our marketing measures should probably be trusted (c). But it doesn’t (~a), so measures should be reviewed (~c). Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ An Argumentative Approach To Policy ‘Framing’. Competing ‘Frames’ And Policy Conflict In The Roşia Montană Case

ABSTRACT: This paper proposes a new theorization of the concept of ‘framing’, in which argumentation has a central role. When decision-making is involved, to ‘frame’ an issue amounts to offering the audience a salient and thus potentially overriding premise in a deliberative process that can ground decision and action. The analysis focuses on the Roşia Montană case, a conflict over policy that led, in September 2013, to the most significant public protests in Romania since the 1989 Revolution.

KEY WORDS: decision, deliberation, frame, framing, metaphor, policy, practical argument, Roşia Montană

Introduction

This article develops an approach to framing theory from the perspective of argumentation theory (Fairclough & Fairclough 2012, 2013) by analyzing the public debate on the proposed cyanide-based gold mining project at Roșia Montană (Romania). It puts forward a view of ‘framing’ as a process of offering an audience a salient and potentially overriding premise that they are expected to use in deliberation leading to decision and action (Fairclough 2015, Fairclough forthcoming b). It also aims to make an empirical contribution to the study of the Roșia Montană case, a policy conflict that has set the Romanian government and a multinational company against the Romanian population and, in September 2013, led to the most intense public protests since the fall of communism. The outcome was the rejection by the Romanian Parliament of a draft law that would have given the green light to the largest open-cast gold mining operations in Europe.

This study is part of a larger project that analyzes a corpus of over 600 Romanian press articles, covering the months of August and September 2013, with a twofold purpose: (a) to develop and test an argumentative conception of the process of framing; (b) to gain insight into how four major Romanian newspapers have attempted to reflect and influence the public debate, by finding out which aspects of the policy conflict were selected and made salient in the media, and how they were intended to function in the process of public deliberation. For reasons of space, we will not analyze this corpus here, but illustrate the framework with a smaller corpus of campaign material (leaflets, slogans, placards, website information).

ROȘIA MONTANĂ: A Brief Overview

Roşia Montană is a commune of 16 villages, located in the Western Carpathians, in an area rich in gold and other precious metals, but also in natural beauty and tradition. It has a recorded history of over 2000 years and has been a gold-mining area since Roman times. The region is however plagued by a range of socio-economic problems which demand a strategy of sustainable development (Plăiaș 2012). The controversial mining project advanced by the Canadian corporation Gabriel Resources Ltd. in partnership with the Romanian state (renamed Roșia Montană Gold Corporation, henceforth RMGC, in 2000) has claimed to provide just such a solution, by “bring[ing] one of the world’s largest undeveloped gold projects to production” (The Roșia Montană Gold & Silver Project: A Project for Romania 2014). The project would require large-scale cyanide-leaching procedures in order to extract an estimated 314 tons of gold and 1,480 tons of silver from 4 open-cast pits over a 16-year period. While the economic benefits to the Romanian state were invariably presented by the corporation as extraordinary, Romania’s projected equity stake in the company was only 19.31%, the other 80.69% being owned by Gabriel Resources, according to company data in 2014. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ A Dialectical Profile For The Evaluation Of Practical Arguments

ABSTRACT: This paper proposes a dialectical profile of critical questions attached to the deliberation scheme. It suggests how deliberation about means and about goals can be integrated into a single recursive procedure, and how the practical argument from goals can be integrated with the pragmatic argument from negative consequences. In a critical rationalist spirit, it argues that criticism of a proposal is criticism of its consequences, aimed at enhancing the rationality of decision-making in conditions of uncertainty and risk.

KEYWORDS: critical discourse analysis, critical rationalism, critical questions, decision-making, deliberation, dialectical profile, policy evaluation, practical argument, uncertainty and risk

Introduction

This paper develops the analytical framework for the evaluation of practical arguments in political discourse presented in Fairclough & Fairclough (2011, 2012), where a more systematic “argumentative turn” was advocated for the field of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). It develops a proposal for a set of critical questions aimed at evaluating decision-making in conditions of incomplete knowledge (uncertainty and risk). The questions are briefly illustrated with examples from the public debate on austerity policies in the UK, following the first austerity Budget of June 2010 (Osborne 2010). For a more detailed analysis of the 2010 austerity debate, see Fairclough (2015).

Reasonable Decision-Making In Conditions Of Incomplete Information

Practical reasoning has been studied in informal logic and pragma-dialectics (Walton 2006, 2007a, 2007b; Walton, Reed & Macagno, 2008; Hitchcock 2002; Hitchcock, McBurney & Parsons, 2001; Garssen 2001, 2013; Ihnen Jory 2012) and sets of critical questions have been proposed for its evaluation. In what follows I will outline my own version of the critical questions for the evaluation of practical arguments, together with their theoretical underpinning, i.e. a critical rationalist view of the function of argument and of rational decision-making (Miller 1994, 2006, forthcoming). On this view, the function of argumentation is essentially critical and the best rational agents can do before adopting a practical or theoretical hypothesis is to subject it to an exhaustive critical investigation, using all the knowledge available to them. The decision to adopt a proposal A is reasonable if the hypothesis that A is the right course of action has been subjected to critical testing in light of all the knowledge available and has withstood all attempts to find critical objections against it. By critical objection I understand an overriding reason why the action should not be performed, i.e. a reason that has normative priority and thus cannot be overridden in the context. Essentially, criticism of a hypothesis is criticism of its consequences, not criticism of any premises on which it allegedly based. A critical rationalist view is anti-justificationist, and rationality is seen to reside in the procedure of critical testing; it is a methodological attitude.

Critical testing will necessarily draw on the knowledge or information that is available to the deliberating agents, and this is almost always limited. How should this knowledge be used if it is to enhance the rationality of decision-making? The critical rationalist answer is that knowledge should be used critically, in order to criticize and eliminate proposals, not inductively, i.e. not in order to seek confirmation of their (apparent) acceptability. Potential unacceptable consequences can constitute critical objections against doing A, unless critical discussion indicates that they should be overridden by other reasons.

Let us consider the case of risk first. If a definite prediction could be made that such-and-such unacceptable consequences will follow from doing A, this would provide an overriding reason why A should not be performed. But such definite predictions about the future are hard to make. On a critical rationalist perspective, rational decision making in conditions of risk can be made, however, without relying on probability calculations, by following a “minimax strategy” which says: “try to avoid avoidable loss” (Miller forthcoming). This can be done by insuring in advance against possible loss (e.g. insuring one’s property against various eventualities), or in the sense of making sure that there is some alternative route or some “Plan B” that one can switch to, should the original proposal start to unfold in an undesirable way, i.e. produce undesirable effects.

Unlike risk, which presupposes some calculation is possible, uncertainty does not involve known possible outcomes and frequencies of occurrence, derived from information about the past, but future developments which cannot be calculated. Incomplete knowledge manifests itself in this case not only as “known unknowns” but also as “unknown unknowns”, and it is impossible to predict how the proposed action, as it begins to unfold, might interact with these. Economic policy, for example, involves primarily uncertainty rather than risk, as it unfolds against a background of unpredictable world events about which little if any calculation of probability can be made. The critical rationalist answer (Miller forthcoming) to the problem of uncertainty says that it is more reasonable to choose a proposal that has been tested and has survived criticism than one which has not been tested at all. In conditions of bounded rationality, a sub-optimal (“satisficing”) solution that is known to work, if available, is preferable both to an extended quest for a maximally rational solution or to the adoption of an untested, new proposal, however promising that proposal may seem. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ The Possibility Of Visual Argumentation: A Point Of View

Abstract: The verbal and the visual are different complementary means for argumentation, and there is an uncontentious fact that visual argumentation exists. And, visual argumentation can learn much more from Frege’s theory of meaning, which is helpful for the theorical basis or the philosophical ground of visual argumentation. Finally, some further far-reaching questions are brought forth, especially about the schemes of visual argumentation, and the relation of visual argumentation to artificial intelligence.

Abstract: The verbal and the visual are different complementary means for argumentation, and there is an uncontentious fact that visual argumentation exists. And, visual argumentation can learn much more from Frege’s theory of meaning, which is helpful for the theorical basis or the philosophical ground of visual argumentation. Finally, some further far-reaching questions are brought forth, especially about the schemes of visual argumentation, and the relation of visual argumentation to artificial intelligence.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, philosophical ground, visual argumentation, the context principle, the scheme of visual argumentation

1. Introduction

The visual usually can convey much more meanings that cannot be expressed as well through the verb. Then, can the visual express an argument or an argumentation?

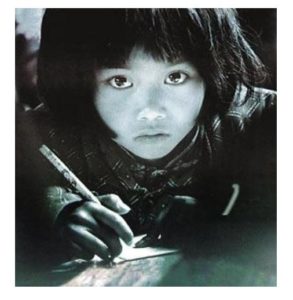

For example, there is a picture (see Figure 1).

When you as an audience see the picture, what would you think? Perhaps there are at least three possibilities:

(1) you don’t know about the related context, so you could not understand what on earth the picture wants to express;

(2) you don’t know about its related context. You don’t care about what it wants to express. You direct your attention at the eyes, the fingers, the color of the picture, and even the pencil, and so on;

(3) you know about the related context, so you could know this is a poster, which is the poster of Hope Project “Big Eyes Girl” in China, and it appeals to the people to donate.

Suppose you could know about the related contexts, and understand what the picture wants to express. Then, as an audience you could have different attitudes to what the poster expresses. For example, three kinds of attitudes are as follows:

Approver A: Yes, I will and prefer to donate to the Hope Project.

Objector B: No, I will not donate to the Hope Project, because I am not very rich, and I myself also need donation.

Objector C: No, I will not donate to the Hope Project, because I don’t believe its organizer. But I prefer to donate to the poor directly.

When the audiences begin their argumentations in their brains, the argumentations seem to take place. Here, some questions will be raised, which are too diversified for a paper, so I will talk some of them roughly:

(1) What are the challenges to the possibility of the concept of visual argumentation (VA for short)? This is about the realistic possibility of visual argumentation.

(2) Why VA is possible in the realm of argumentation? That is to say, how to make sense of the logical possibility of VA?

(3) How can the visuals express an argument or argumentation[i]? And some further questions raised by VA, for example, the schemes of visual argumentation, and the relation of VA to artificial intelligence (AI for short). Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ Persuasion,Visual Rhetoric And Visual Argumentation

Abstract: It is often said that images are excellent persuasive means. However, if images are persuasive, can they also be argumentative? After discussing authors who have tried to fill the gap between rhetoric and argumentation (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, Reboul, Bonhomme), I will argue that the same figures or tropes can have both a persuasive and an argumentative function.

Keywords: metonymy, persuasion, visual argumentation, visual rhetoric.

1. Introduction

The relationship between visual rhetoric and visual argumentation is a topic to which several essays have been dedicated. Some scholars deal with it in a general way (Blair, 2004; Kjeldsen 2012). Others focus on figures or tropes in particular (for antithesis, van Belle, 2009). Indeed, it has becoming a sub-field in the domain of visual argumentation. That said, the way in which visual rhetoric and visual argumentation have been related is not completely satisfactory. I will try to show that most attempts to link rhetoric and argumentation are based on the assumption that figures of rhetoric are above all persuasive. This assumption has a dramatic consequence upon visual argumentation, specifically because one argument against visual argumentation is that images are merely persuasive. As a result, considering visual rhetoric as persuasive would not reinforce visual argumentation, but rather critiques against it. Furthermore, another critique must be taken into account: in the frequent case of mixed media, i.e. when an argument is displayed in both words and images (such as in ads or commercials), the text alone is supposed to be argumentative, while the image would be merely persuasive (Adam & Bonhomme, 2005, p. 194 & 217).

So, in the first part of this paper, I will examine some of the principal ways figures of rhetoric and argumentation have been related in order to determine the extent to which figures have been considered as arguments. Then, in the second part, I will argue that some figures of rhetoric can be persuasive and argumentative at the same time.

Simply stated, I am interested in the argumentativity of figures. In saying this, I am using a French concept (argumentativité) that was coined by Ducrot and is used in the French theory of argumentation in order to refer to figures (Bonhomme, 2009; Plantin, 2009). This concept essentially suggests that an utterance can have an argumentative value instead of being limited to providing merely informational value (Anscombre et Ducrot, 1986, p. 91). Such an argumentative value comes from the fact that we can find, in an enunciate, elements that allow for a given conclusion by way of a commonplace, which Ducrot calls a topos (Ducrot, 1992). However, this concept is used in a slightly different way when applied to figures: in this case, it refers to their argumentative value, which can be considered as persuasive or argumentative, in this case when figures provide reasons to support a claim. Note that in what follows, I use the adjective “argumentative” with this restrictive meaning, unlike those who use it in a broader way, i.e. including all mean of influencing the addressee.[i] Read more