Reshaping Remembrance ~ Die Stem

1.[i]

1.[i]

Music is high or low. It can ascend or descend (like mountains and valleys) with an ascending run or descending scale. It is here, close to home (tonic), or there, close to relatives (relative or parallel minor/major, perhaps dominant or subdominant keys). Sometimes it moves, as is envisioned in Schoenberg’s idea of tonality, to far-off reaches of larger tonal geographies, to the furthest of such places before it returns (if it returns at all) to the known world of the tonic. Music as a kind of res extensa.[ii] Orchestration could be airy and spacious in the hands of Webern, or constructivist and muscular when done by Brahms. Music creates horizontal contours and arches through the distances between notes (intervals). These distances are determined during performance by controlling the time-space separating the end of one tone and the beginning of the next (articulation). Music is architecturally monumental in form, like a Beethoven symphony, or it is in expression and form as intimate as the salon.

We cannot approach music in language without the metaphors of place and space. Individual combinations of tones (musical ‘works’) constitute designated spaces. When these spaces become known after frequent visits, they become inhabited by cultural memory. The evocative nature of such spaces is inherent to the fact that the sentiment (emotional and/or cultural) is felt precisely, but cannot be expressed accurately in language. It is a language-resistant space. To consider Die Stem as collective memory depends on this metaphorical understanding of music in general, and of a specific work in particular. This is not a perspective that demands clarification of the song’s history. C.J. Langenhoven’s poem is only the foundation of this place. M.L. de Villiers’s melody is only the outer walls thereof and Hubert du Plessis’s official orchestration only the interior decorating.[iii]

Questions on memory and remembering and of how these things relate to this particular text, are not questions about historiography. The imagination in search of memory has to find more poetic avenues to knowledge.

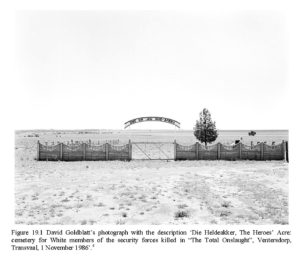

Figure 19.1 David Goldblatt’s photograph with the description ‘Die Heldeakker, The Heroes’ Acre: cemetery for White members of the security forces killed in “The Total Onslaught”, Ventersdorp, Transvaal, 1 November 1986’. [iv]

The closing phrase of Die Stem is literally displayed ‘triumphantly’ (the character indication in the music) as meaning-giving banner over this demarcated space. It lends definition to the space of the military cemetery. Does the reader hear it? The two security force members buried there are lifted up by the contour of the melody: B flat-A flat-G-B flat-C-D-E flat. The dotted rhythmical introduction to the phrase, undergirded by the secondary dominant harmony, assuages doubt, presses forward, aims towards the solution at the end of the phrase. The end is comforting as an end. It brings us home. Goldblatt’s photograph dates from 1986. It is understandable if one hears Die Stem in this time as a military song; the contours and rhythms and harmonies sound like bulwarks against the enemy, as encouragements to those who would doubt the final victory. However, for André P. Brink, Die Stem is also the song of torture in the seventies:

… every time the rebel leader is arrested, and tortured, and killed, leading to new protest, and to new martyrs; this goes on until a deadly silence remains, lasting an agonising eternity, a silence out of which, almost inaudible at first, the national anthem rises while a group of folk dancers in white masks begin to dance on the bodies of the martyrs.[v]

It is also this ‘Stem’ that, at the end of J.M. Coetzee’s Age of iron, provides the sound track to the author’s nightmarish vision of hell. ‘I am afraid’, says the dying Mrs Curran, ‘of going to hell and having to listen to Die stem (sic) for all eternity’.[vi] Die Stem that accompanies the coffin of Milla Redelinghuys into her grave at the end of Marlene van Niekerk’s Agaat has a different tenor. When the Grootmoedersdrift farm is taken into possession by the coloured woman, Agaat, who was formed by the white woman who loved and rejected her, it is Die Stem that articulates ambiguously change and continuity:

Gaat making people by the graveside sing the third verse of Die Stem: … When the wedding bells are chiming, Or when those we love depart. And then all eyes on me for: … Thou dost know us for thy children …We are thine, and we shall stand, Be it life or death to answer Thy call, beloved land! Wake up and smell the red-bait, as Pa would have said. Poor Pa with his ill-judged exclamations. Did at least make a note for my article on nationalism and music. Thys’s body language! The shoulders thrust back militaristically, the eyes cast up grimly, old Beatrice peering at the horizon. The labourers, men and women, sang it like a hymn, eyes rolled back in the head.

Word-perfect beginning to end. Trust Agaat. She would have no truck with the new anthem.[vii]

But how did historical reception develop the fascistic timbre that characterized performances and receptions of Die Stem in the 1980s, so apparent in the quotation above? Surely there was a time when Die Stem was a freedom song for Afrikaners, an alternative text for collective musical mobilization to God Save The Queen. This essay wants to connect the cited examples of fiction-mediated memories of Die Stem to the historical process represented in FAK (Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge, directly translated as Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Societies) archival documents from the 1950s.

In 1952, five years before Die Stem became the only official anthem of South Africa, the Afrikaanse Kultuurraad (Afrikaans Culture Board) of Pretoria launched an initiative to elicit ‘opinions by three authorities regarding suitable occasions when an anthem should be sung or played’. From Stellenbosch, Dr C.G.S. (Con) de Villiers wrote as follows:

I am of inclination and education extremely conservative, particularly when it concerns the holy things of our volk. And Die Stem has become one of those. I even lamented it bitterly that Die Stem was sung and played at the end of rugby football matches in England … There is for me only one indicator to justify singing it: does the meeting possess poids et majesté in the Calvinist sense? Then Die Stem can be sung![viii]

De Villiers’s answer can only be quoted in part. In the rest of the letter he also expresses opposition against the singing of Die Stem at political meetings because, as a member of the National Party, he would find it ‘sad if the Sappe [South African Party] viewed Die Stem as the calling card of the [National] Party’. For De Villiers the most terrible violence against Die Stem constitutes ‘a young lady who goes to sit at the piano and makes her own, apocryphal harmony to the tune’.[ix]

It is clear that by 1952 Die Stem had already become for De Villiers one of the ‘holy things’ of the Afrikaner, a place of worship. His dislikes point to possible contaminating influences: sport, politics and ‘young ladies’. With regard to the latter, the danger of contamination is located specifically in the harmony and not any of the other musical parameters. Historically (one thinks here of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Council of Trent), this fear can be connected to a philosophical and ideological privileging of the word, the clarity of which is endangered by complicated vertical musical activity. More about this later.

For De Villiers, Die Stem as holy space is a space of good taste and of higher things in life. These political and gender biases expressed as pseudo-aesthetic judgements can also be found in his published writings. Mussolini’s signed portrait displayed in his lounge linked with his Verdi worship, the influence of English songs that clung like a bad odour to his past, the memories of the ‘passionate, barbaric Gypsy folk dances that the young Jew played for the modest, civilized Afrikaner family’;[x] coordinates aiding the reconstruction of De Villiers’s camp ‘poids et majesté’. Die Stem as ‘soete inval’.[xi]

Dr H.C.E. Bosman, then secretary of the Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns [South African Academy for Sciences and Arts], writes on 16 June 1952 that Die Stem might be sung at ‘occasions where the feeling of the nation is naturally expressed’. For him, this includes ‘general national festivals [Volksfeeste], Dingaan’s Day festivals [16 December], Union Day [31 May], Hero’s Day [on Paul Kruger’s birthday, 10 October], Van Riebeeck’s Day [6 April], parliamentary events, functions where the provincial and city administrations are involved’.[xii] Bosman does not deem Die Stem inappropriate at big political meetings, and is of the opinion that it can also be sung at ‘cultural events, camping-out gatherings [laertrekke], folk dances, big events for the young, international matches or events’. Excluded from his list are ‘weddings, dances, cocktail parties, cinemas, camps, plays, concerts and picnics’. He justifies these exclusions by saying that such performances would be continuing ‘the English practice, which is in part monarchical-traditional, and in part deliberate imperialist propaganda’.[xiii]

Die Stem, therefore, is an anti-British space, but even more: it occupies the places of the state. In this emerging discourse, Die Stem as symbol is no longer a space being occupied, but an object with a place. For Prof A.N. Pelzer of the University of Pretoria, a national anthem [Volkslied] is

… an elevated utterance of the fixed aspirations that live deep in the soul of a nation. It indicates the longing that nation and State should continue to exist and serves to unite the nation into an indivisible whole and to strengthen it in realising the high ideals expected for nation and state. It rises above what is temporary and points to everlasting and imperishable values.[xiv]

Die Stem is thus a metaphysical space of aspiration and idealism. According to Pelzer it can only be honoured by performing it at ‘events where the aim of the event is not limited to the event itself, but points to the cultivation of values that will be meaningful to the future’. He also fears that Die Stem could be misused by subjecting it to the same ‘lowly treatment of the English anthem’.[xv] The transcendental, we are given to understand, is not an English space.

The intervention of the Afrikaans Culture Board of Pretoria on this important matter forced the FAK to conduct a further investigation. Asked about their opinion, the South African Teachers’ Union (SATU) recommended the singing of the song at school functions in order to ‘create amongst the youth of our country healthy love for the fatherland’.[xvi] After all this consultation, a decision was taken at a meeting of the FAK’s Music Commission on 25 April 1953:

The meeting recommends to the FAK that the following be propagated to the nation:

a) That ‘Die Stem’ be sung only at events where the value of representing the country is evident;

b) that care should be taken to prevent ‘Die Stem’ being used in the same way as [God save] ‘The Queen’;

c) that where ‘Die Stem’ is played, it is played as a whole and not only in part;

d) that, at the end of events, other songs, like Afrikaners Landgenote, be sung.[xvii]

It is important to articulate clearly what was happening here: control, anti-British sentiment, the propagation of a museum aesthetic alienated from ordinary people, the creation of a perception that Die Stem was not just a song, but a mystic key to the independence of the Afrikaner nation. It is therefore not surprising that in 1957, when Die Stem was proclaimed the only official anthem of the Republic, no superlative sufficed to express the joy amongst the song’s supporters in the FAK. A telegram of congratulations was sent to the prime minister, J.G. Strydom:

To: The Honourable Prime Minister, House of Assembly, Cape Town

The declaration recognizing The Call of South Africa as the official and only anthem of South Africa is for everyone of the thousands of members of the FAK a source of the highest ecstasy. With this act, an old national ideal has been accomplished and one of the most important milestones on our road to full nationhood has been achieved. Having achieved this, the last of the former conqueror’s symbols that have towered over us, has disappeared. We honour Your Excellency personally, and also every member of the government.

From: Secretary FAK[xviii]

Highest ecstasy! One of the most important milestones on our road to full nationhood. Die Stem had become the Afrikaner score to nationhood. Three days after this telegram was dispatched, the Chairman of the FAK, Prof H.B. Thom, wrote a congratulatory letter to J.G. Strydom in which he formulated the importance of Die Stem as follows:

You have led the Afrikaners, and indeed the whole of South Africa, to advance an important step on the road to full, unqualified spiritual independence, which is such an indispensable prerequisite for real economic and political independence. I am convinced that History will one day acknowledge the outstanding contribution of your leadership in connection with our national hymn.[xix]

Full, unqualified spiritual independence. This is one way of articulating the meaning of this song in the ears of Afrikaners of that time. But even after Die Stem was adopted as the only national anthem of the republic, the desire of the Afrikaner leadership to control it did not abate. Spiritual independence is, alas, no substitute for good taste. Not only was the melody required to remain the property of the volk, but the cancerous corruption against which Con de Villiers had warned – deviant harmony – also had to be removed from Die Stem as alien to the volk. The minutes of a FAK Music Commission of 12 March 1960 documents the following discussion:

Mr A. Hartman reported that the SABC wants to record and market a LP of Gideon Fagan’s arrangement of Die Stem van Suid-Afrika, and then to request that the Government approve this as the accepted official arrangement. The Music Commission did not view this arrangement as acceptable, especially since it radically changes the harmony. The Commission favoured the arrangement of Rev M.L. de Villiers.

Mr A. Hartman also mentioned that Dr F.C.L. Bosman, Chairman of the South African Music Board, had consulted Prof [Friedrich] Hartman (sic) of the University of the Witwatersrand about this matter. The opinion of the latter, written in English, was read to the Commission. From this it transpired that he attacked Rev De Villiers’s arrangement on technical points.

Mr A. Hartman’s opinion was that the stamp of approval should be given to that which fits with our national tradition [‘volkstradisie’] and not necessarily to the best technical arrangements.

Dr G.G. Cillié pointed out that Prof Hartman (sic) had praised the arrangement of Gideon Fagan in such superlatives and rejected that of Rev M.L. de Villiers so radically, that they could emphatically conclude that this was not an objective and scientific opinion, making it possible to reject it in its entirety.[xx]

On 14 March 1960, a letter was sent on behalf of the Music Commission of the FAK to Prof H.B. Thom, presumably written by the secretary of the FAK. In this letter, an ‘urgent matter’ was raised, namely the SABC’s planned recording of Die Stem on LP. The source of unhappiness was the Fagan ‘four-part arrangement’, so lavishly praised by Prof Friedrich Hartmann:

We have also seen the (English) remarks of Prof Hartman. Briefly, the contents thereof comes down to the fact that the M.L. de Villiers arrangement is hopeless and the Fagan arrangement faultless. The Music Commission is of the opinion that such an absolute condemnation of the one and absolute extolling of the other cannot be accepted as a scientifically objective judgment.

This was followed by the coup de grâce:

The tempo of 60 crotchets per minute of the Fagan arrangement is unacceptably slow and seemingly an imitation of the tempo of God Save the Queen.[xxi]

Die Stem is thus anglicized by making it sound more like a hymn and less like a march. But the antagonism against everything English, from the character of the English anthem to the continuing references to the negative remarks being made ‘in English’, makes it clear that these motives are strongly anchored in nationalist discourses. The existence of an underlying mistrust in ‘the best technical settings’ is clear, and the possibility that this mistrust could be located in the (unconscious) confirmation of the Afrikaans word as potentially vulnerable to ‘alien’ harmony, is a rich idea. The writer of the letter to Thom explains the petty Afrikaner politics behind this polemic step by step. In short it constitutes a ‘devious plan’ by the ‘enemies of the volk’ to install Gideon Fagan as the principal conductor of the SABC, instead of appointing the chairman of the Music Commission of the FAK (Anton Hartman). Whether Friedrich Hartmann’s opinion could be motivated musically or not, was not deemed relevant:

The opinions they canvassed are exclusively from people who are not part of our Afrikaner nation’s ideals. If folk songs and the harmonization of such songs were to be judged purely on musical merits, Die Stem would never have been adopted in the first place.[xxii]

Subsequently, the FAK also sent Dr H.F. Verwoerd a letter with an appeal to the effect that the M.L. de Villiers setting be recognized by the government as official arrangement.[xxiii]

3.

What can be deduced from the pitiful politics about harmonization, the suitability of places and events, the discourses on dignity and gravitas? At least the fact that there is nothing neutral about this song, and that the political ballast weighing down Die Stem is not only of our time, imagined retrospectively by the ‘enemies of the Afrikaner’, but that it has been historically conceived and understood by Afrikaners themselves. Also that the restrictive control that would characterize the Afrikaner Republic would stunt this song in self-glorified mediocrity. Finally that music, too, could not escape the machinations of the secret Broederbond.

Die Stem as Afrikaans place of memory: Goldblatt’s tragic emptiness, Brink’s martyr’s dirge, Van Niekerk’s set-piece on the burial of the Republic, Coetzee’s version of hell, Con de Villiers’s ‘poids et majesté’, Anton Hartman’s national tradition, H.B. Thom’s ‘spiritual independence’. Different conflicting memories, representing different histories.

NOTES

i. The full title of the anthem is Die Stem van Suid-Afrika, officially translated into English as The Call of South Africa. Throughout this essay the anthem will be referred to only as Die Stem.

ii. Compare the discussion on the rhetoric of tonality in Brian Hyer’s ‘Tonality’, in: T. Christiensen (ed.), The Cambridge history of Western music theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2002, 726-752, esp. p. 733.

iii. This essay is not about the history or the ideological context and meaning of Die Stem. More can be read about these aspects in S. Muller, ‘Exploring the aesthetics of reconciliation: rugby and the South African national anthem’, in: SAMUS 21 (2001), 19-38; See also W. Lüdemann’s ‘”Uit die diepte van ons see”: an archetypal interpretation of selected examples of Afrikaans patriotic music’, in: SAMUS 23 (2003), 13-42.

iv. D. Goldblatt, South Africa: the structure of things then. Cape Town: Oxford University Press 1998, 154 and 243.

v. A.P. Brink, Looking on darkness. London: W.H. Allen, 1974, 308.

vi. J.M. Coetzee, Age of iron. London: Penguin, 1990, 181.

vii. M. van Niekerk. Agaat. tr. Michiel Heyns. Cape Town: Jonathan Ball and Tafelberg 2006, 675.

viii. Compare file PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

ix. Compare file PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

x. Compare Soete inval: nagelate geskrifte van Con de Villiers. Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1979, 26-27 and 50-51. Also see Die sneeu van anderjare. Cape Town: Tafelberg 1976, 72. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xi. De Villiers’s flat was situated in a block called Soete Inval, approximately translated as ‘gentle strains’.

xii. File PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xiii. File PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xiv. File PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xv. File PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xvi. See the letter of 14 February 1953, PV 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

xvii. Compare the minutes of the meeting by the Music Commission, 25 April 1953, PV 202 1/2/3/4/2/2/1, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author. Also see Appendix to the agenda of the Music Commission meeting of 6 July 1954, entitled ‘Verslag van die FAK-kommissie insake “Die Stem” soos gewysig deur die Afrikaanse Nasionale Kultuurraad’ [‘Report of the FAK-Commission regarding “Die Stem” as modified by the Afrikaans National Culture Board’], PV 202 1/2/1/4/2/2/1, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

xviii. See telegram of 3 May 1957, PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xix. Letter of H.B. Thom to J.G. Strydom, 6 May 1957, PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xx. Minutes of a meeting by the FAK Music Commission, 12 March 1960, PV 202 1/2/3/4/2/2/3, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xxi. File PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xxii. Letter to H.B. Thom, 14 March 1960; File PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

xxiii. The letter is dated 21 March 1960. The Prime Minister’s Office acknowledged receipt on 28 March 1960 and a comprehensive answer was sent to the FAK by the secretary of the Prime Minister on 25 May 1960. In this letter the government wisely decided to remain neutral and not choose sides with regard to ‘all harmonisations or arrangements of the composition for orchestra or voices or anything else’, with the understanding that such arrangements should ‘stay within the framework of the acknowledged composition and be performed with dignity and devotion at suitable occasions’. Translated from the Afrikaans by the present author.

References

Unpublished

PV 202 1/2/1/4/2/2/1, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

PV 202 1/2/3/4/2/2/1, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

PV 202 1/2/3/4/2/2/3, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

PV 202 2/4/1/3/1/4, INEG, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

Published

Brink, A.P. Looking on darkness. London: W.H. Allen 1974.

Coetzee, J.M. Age of iron. London: Penguin 1990.

Die sneeu van anderjare. Cape Town: Tafelberg 1976.

Goldblatt, D. South Africa: the structure of things then. Cape Town: Oxford University Press 1998.

Hyer, B. ‘Tonality’, in: T. Christiensen (red.). The Cambridge history of Western music theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2002, 726-752.

Lüdemann, W. ‘“Uit die diepte van ons see”: an archetypal interpretation of selected examples of Afrikaans patriotic music’, in: SAMUS 23 (2003), 13-42.

Muller, S. ‘Exploring the aesthetics of reconciliation: rugby and the South African national anthem’, in: SAMUS 21 (2001), 19-38.

Soete inval: nagelate geskrifte van Con de Villiers. Cape Town: Tafelberg 1979.

Van Niekerk, M. Agaat. tr. Michiel Heyns. Cape Town: Jonathan Ball and Tafelberg 2006.