ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ A Study Of Undergraduate And Graduate Students’ Argumentation In Learning Contexts Of Higher Education

Abstract: This study sets out to examine to what extent the arguments used by undergraduate and graduate students refer to scientific notions and theories related to the discipline taught in the course. The results of this study indicate that only graduate students advance arguments that refer to scientific notions and theories strictly or somehow related to the discipline taught in the course, whereas undergraduate students typically advance arguments based on common-sense knowledge and previous personal experience.

Keywords: Argumentative Strategies, Higher Education, Pragma-Dialectical Approach, Qualitative Research, Student-Teacher Interaction

1. Introduction

In the learning contexts, argumentation is not a heated exchange between rivals that results in winners and losers, or an effort to reach a mutually beneficial compromise; rather it is a form of “logical discourse whose goal is to tease out the relationship between ideas and evidence” (Duschl et al., 2007, p. 33). Argumentation enables students to engage in knowledge construction, shifting the focus from rote memorization of notions and theories to a complex scientific practice in which they construct and justify knowledge claims (Kelly & Chen, 1999; Sandoval & Reiser, 2004). Notwithstanding, current research indicates that learning how to engage in productive scientific argumentation to propose and justify an explanation through argument is difficult for students. Thus, empirical research that examines how students generate arguments has become an area of major concern for science education research.

The present study intends to provide a further contribution to the line of research on student-generated arguments. It specifically focuses on the learning context of higher education and sets out to investigate the arguments used by undergraduate and graduate students in Developmental Psychology during the disciplinary discussions with their teacher and with their classmates, i.e., task-related discussions concerning the discipline taught in the course. In particular, the objective of the present study is to verify the following two hypotheses:

1. “Undergraduate students draw their arguments from common sense and personal experience more often than graduate students”.

2. “Graduate students put forth arguments that refer to scientific notions and theories strictly or somehow related to the discipline taught in the course, i.e., Developmental Psychology, more often than undergraduate students”.

These two hypotheses will be verified by means of a small-scale corpus study, and this certainly limits the generalizability of the results obtained by the present. A larger database would probably permit more quantitatively reliable data for certain statistical relationships, thus drawing conclusions of general order. However, the careful study of a small number of conversations will allow a more penetrating “data-close” analysis of the argumentative dynamics in the classroom. In order to focus on the arguments used by students, the object of investigation will be the argumentative discussions between students and teacher, as well as among students, occurring during their ordinary lessons, rather than an ad hoc setting created to favour the beginning of argumentative discussions. Tools developed in argumentation theory will be useful in this respect as they can be employed to respond to this need. The analytical approach for the selection of the students’ arguments is, in fact, the pragma-dialectical ideal model of a critical discussion (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992, 2004).

The paper is structured as follows: in its first part, a concise review of the most relevant literature on argumentation in learning contexts of higher education will be presented. Afterwards, the methodology on which the present study is based and the results of the analyses will be described. In the last part of the article, the results and the conclusions drawn from this study will be discussed.

2. Argumentation studies in learning contexts of higher education

The studies focusing on the argumentative practices in higher education have brought to light relevant insights in the fields of education and argumentation theory. In particular, two main lines of research need to be distinguished within these studies.

The first line of research aims to single out the cognitive skills that can be improved through argumentative practices in the classroom. Overall, the results of these studies indicate that favoring argument debates in the classroom can enhance students’ motivation and engagement (Chin & Osborne, 2010; Hatano & Inagaki, 2003), and help them detect and resolve errors (Schwarz et al., 2000). A series of other studies have also shown that engagement in constructing arguments enhances students’ knowledge by promoting conceptual change (e.g., Nussbaum & Sinatra, 2003; Wiley & Voss, 1999), and that the engagement in argumentative small- or large-group discussions improves conceptual understanding (Andrews, 2009; Alexopoulou & Driver, 1996; Mason, 1996, 2001).

The second line of research aims at investigating students’ argumentative skills, and how such skills can favor or disfavor the learning process. In this respect, the role of argumentation in the academic context is currently stressed by a growing literature that emphasizes how students rarely use criteria that are consistent with the standards of the scientific community to determine which ideas to accept, reject, or modify. For example, the work of Hogan and Maglienti (2001) and Linn and Eylon (2006) suggests that students often rely on inappropriate criteria such as the teacher’s authority or consistency with their personal beliefs to evaluate the merits of a scientific explanation. This research suggests that students rarely use criteria based on theories and scientific models. Other research suggests that students often do not use sufficient evidence (Sandoval & Millwood, 2005) or struggle to understand what counts as evidence (Sadler, 2004). Moreover, McNeill and Krajcik (2007) found that if students are confronted with large amounts of data, they often encounter difficulties differentiating between what is relevant and what is irrelevant.

Within the research strand on students’ argumentative skills, a series of studies devoted attention to the problem of constructing students’ knowledge, taking into account their previous beliefs (Macagno & Konstantinidou, 2013; Sampson & Clark, 2008; Driver et al., 2000; Jiménez-Aleixandre et al., 2000; Kelly & Takao, 2002). For instance, Alexander, Kulikowich, and Schulze (1994) have shown that previous knowledge in the domain is a significant predictor of comprehension of the arguments advanced in support of a scientific theory. In a case study analysis of argumentative discourse among high school science students, von Aufschnaiter et al. (2008) suggest that the quality of argumentation itself is mediated by students’ prior knowledge and familiarity with the content. Thus, high-level argument requires high-level knowledge of the content. According to the authors, students can engage effectively in argumentation only on content and levels of abstraction that are familiar to them. In the same vein, Sadler and Zeidler (2005) investigated the significance of prior knowledge of genetics for the argumentation of 15 undergraduate students on six cloning scenarios. The findings of this study indicated that students with more advanced genetics understanding demonstrated fewer instances of reasoning flaws, such as lack of coherence and contradiction of reasoning within and between scenarios, and were more likely to incorporate content knowledge in their argumentation than students with more a naïve understanding of genetics.

Overall, despite differences in methodology and interpretation, the studies on the argumentative skills of students in the learning contexts of higher education have had the merit to show that students are able to understand and generate an argument, and to construct justifications in defence of an opinion. However, the results of these studies have also indicated that students often do not base their decisions to accept or reject an idea on available evidence and appropriate reasoning. Rather, they tend to use inappropriate reasoning strategies to warrant one particular view over another and distort, trivialize, or ignore evidence in an effort to reaffirm their own ideas.

The present study intends to provide an innovative and relevant contribution to the recent literature on student-generated arguments in the learning contexts of higher education. In the next sections of the paper I will present the research design, as well as the main results of this study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Corpus

The present investigation is based on a corpus of sixteen video-recorded separate lessons of one Bachelor’s degree (sub-corpus 1) and one Master’s degree course (sub-corpus 2), constituting about 24 hours of video data. The length of each recording varies from 84 to 98 minutes. The two courses have been selected according to the following criteria:

i. similar number of students (about 15 students);

ii. similar disciplinary domain (both courses considered handle themes in the area of developmental psychology);

iii. both courses are taught by the same teacher in English language.

Sub-corpus 1 consists of 8 video-recorded lessons of the third year elective course “Adolescent Development: Research, Policy, and Practice” of the Bachelor’s degree at the University College of Utrecht (UCU). Sub-corpus 2 consists of 8 video-recorded lessons of the first year elective course “Human development and developmental psychopathology” of the Master’s degree program Development and Socialization in Childhood and Adolescence (DASCA) at the Utrecht University (UU).

3.2. Population

The sub-corpus 1 is constituted by 14 students, 4 boys and 10 girls. All the students at the time of data collection were in their early 20s (M = 21.80; SD = 1.80). There was no significance difference of age between boys (M = 21.89; SD = 2.66) and girls (M = 21.74; SD = 1.20). The sub-corpus 2 is constituted by 16 students, who were all girls. Most of the students at the time of data collection were in their early 20s (M = 23.00; SD = 1.60).

Before starting the last lesson of the course (December 2013), both undergraduate and graduate students were asked (i) to rate in a scale from 1 (none) to 9 (excellent) their own ability to communicate in English language, (ii) if they had already took an academic course in Developmental Psychology, and (iii) to rate in a scale from 1 (none) to 9 (excellent) the level of their previous knowledge in Developmental Psychology, i.e., before taking the course. As for the ability to communicate in English language, in a scale from 1 to 9 the average score of the undergraduate students, according to their own perception, was M = 8.28, whilst the average score of the graduate students was slightly lower M = 7.56. The most part of the students did already take an academic course in Developmental Psychology, both undergraduate (Yes N= 12; No N= 2) and graduate level (Yes N= 15; No N= 1). In regard to the level of their previous knowledge of the discipline taught in the course, in a scale from 1 to 9 the average score of the undergraduate students, according to their own perception, was slightly lower (M = 6.35) than graduate students (M = 7.25).

4. Analytical approach

4.1. The Ideal Model of a Critical Discussion

The approach adopted for the analysis is the pragma-dialectical ideal model of a critical discussion (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, 2004) that proposes an ideal definition of argumentation developed according to the standard of reasonableness: an argumentative discussion starts when the speaker advances his/her standpoint, and the listener casts doubts upon it, or directly attacks the standpoint. Accordingly, confrontation, in which disagreement regarding a certain standpoint is externalized in a discursive exchange or anticipated by the speaker, is a necessary condition for an argumentative discussion to occur.

In the present study, this model is assumed as a grid for the analysis, since it provides the criteria for the selection of the argumentative discussions and for the identification of the arguments put forth by students.

4.2. Criteria used to select argumentative discussions

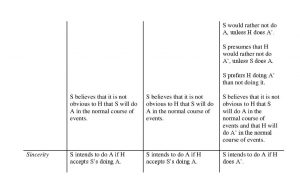

The analysis we present in this paper will be limited to and focused on the study of what the pragma-dialectical of critical discussion defines as analytically relevant argumentative moves, namely, “those speech acts that (at least potentially) play a role in the process of resolving a difference of opinion” (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004, p. 73). If there is not a difference of opinion between two parties, therefore, we cannot talk of an argumentative discussion between them. For the present study, only the discussions that fulfill two of the following three criteria, one between i.a and i.b and always the ii., were selected for analysis:

i.a at least one standpoint concerning an issue related to the discipline taught in the course put forth by one or more students is questioned – either by means of a clear disagreement or by means of a doubt – by the teacher or by (at least) one classmate,

i.b at least one standpoint concerning an issue related to the discipline taught in the course put forth by the teacher is questioned – either by means of a clear disagreement or by means of a doubt – by one or more students;

ii. at least one student advances at least one argument either in favor of or against the standpoint being questioned.

The argumentation data for each session were obtained by reviewing both the video recording and the corresponding transcript. In a first phase, all the argumentative discussions between students and teacher or among students arisen around an issue related to the discipline taught in the course that occurred in the corpus of sixteen separate lessons were selected (N= 94). Subsequently, for the scope of the present study, I only referred to the argumentative discussions in which at least one student advanced at least one argument either in favor of or against the standpoint being questioned (N= 66).

4.3. Criteria used to identify and distinguish students’ arguments

In order to identify the arguments put forth by students, the analysis is focused on the third stage of the model of a critical discussion, i.e., the argumentation stage. As stated by van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1992, p.138), in this stage the interlocutors exchange arguments and critical reactions to convince the other party to accept or to retract his/her own standpoint: “The dialectical objective of the parties is to test the acceptability of the standpoints that have shaped the difference of opinion”. Accordingly, in line with the pragma-dialectical approach, we considered as students’ arguments only the argumentative moves by students that aim to support, explain, justify and defend their own position.

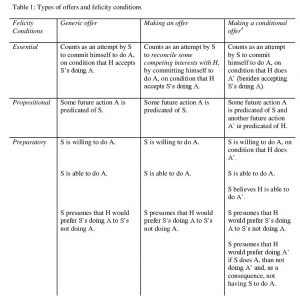

Once identified, the arguments put forth by students were distinguished according to the following two criteria:

– the argument refers to scientific notions and theories strictly or somehow related to Developmental Psychology (hereafter, SCIENCE ARG).

– the argument refers to student’s personal experience or to any other information that does not refer to scientific notions and theories strictly or somehow related to Developmental Psychology (hereafter, NO SCIENCE ARG).

An example of SCIENCE ARG is the second part (in Italic) of the following discourse by a student: “I think that Piaget’s notion that children’s development must necessarily precede their learning is wrong, because according to Vygotsky learning is a social phenomenon and it come before development”. An example of NO SCIENCE ARG is, instead, the first part (in Italic) of the following discourse by another student: “In my school, bullies were above all rich and spoiled guys. I wouldn’t say that bullies typically come from poor families”.

5. Results

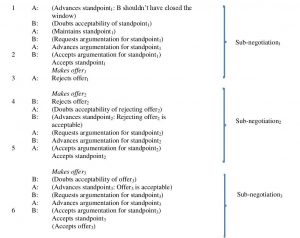

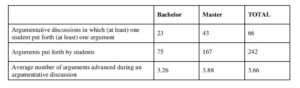

Within the total of N= 66 argumentative discussions analyzed, the graduate students advanced arguments in support of their standpoint more frequently than the undergraduate students. Overall, the undergraduate students advanced at least one argument in N= 23 discussions, for a total number of N= 75 arguments (average number of arguments advanced during an argumentative discussion N= 3.26). These arguments were in most cases advanced during student to student interactions (N= 51; 68%), whilst a fewer number of arguments were observed during student-teacher interactions (N= 24; 32%). The graduate students advanced at least one argument in N= 43 discussions, for a total number of N= 167 arguments (average number of arguments advanced during an argumentative discussion N= 3.88). Similar to what was observed in regard to undergraduate students, a higher number of arguments were found in student to student interactions (N= 95; 57%) than in student-teacher interactions (N= 72; 43%).

A detailed description of the number of arguments put forth by undergraduate and graduate students is presented below, in Table 1:

In order to present the results of this study, a selection of excerpts of talk-in-interaction representative of the results obtained from the larger set of analyses conducted on the whole corpus of students’ arguments will be presented.

5.1. Undergraduate Students’ Arguments

The analysis of the arguments put forth by the 14 undergraduate students involved the N= 23 argumentative discussions arisen around an issue related to the discipline taught in the course in which they put forward at least one argument to support their own standpoint, for a total number of N= 75 arguments. The findings show that in large part the undergraduate students put forth NO SCIENCE ARG (N= 66; 88%), both in interactions with their classmates (N= 50 out of N= 51 total arguments put forth in interactions with their classmates) and with the teacher (N= 16 out of N= 24 total arguments forth in interactions with their teacher).

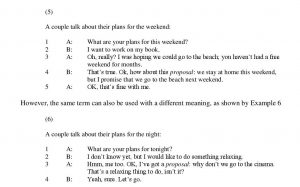

In the following example we can see how an undergraduate student (STU2F) put forth a NO SCIENCE ARG (in Italic in the excerpt) (line 9: “there is not a mother that would accept to kill her son. it is not culture it is the nature of human beings”) to oppose a NO SCIENCE ARG (in Italic in the excerpt) (line 2: “otherwise slavery wouldn’t have been permitted. at a certain time at a certain place, it was possible”; and line 4: “at a certain time at a certain place, it was possible”) previously advanced by one of her classmate (STU14M) during a discussion favoured by the teacher concerning the cultural approach and its implications (line 1):

Excerpt 1

Lesson 3. Min. 38:12. Participants: teacher (TEACH), students (STU2F; STU14M).

1. *TEACH: according to the cultural approach, all the values, what is right or

what is wrong is cultural specific, they depends on culture […] what do you think about this?

2. – *STU14M: yes, is right. otherwise slavery wouldn’t have been permitted

3. – *TEACH: yes, good point

4. – *STU14M: at a certain time at a certain place, it was possible

5. – *TEACH: right

6. – %pau: 2.0 sec

7. – *STU2F: not everything, though

8. – *TEACH: what?

9. – *STU2F: not everything is acceptable. there is not a mother that would

accept to kill her son. it is not culture it is the nature of human beings

[…]

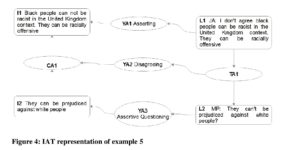

In the corpus, undergraduate students put forth SCIENCE ARG almost exclusively in interactions with their teacher (N= 8 out of N= 9 total SCIENCE ARG put forth in interactions with their teacher). A clear example of the use of this type of argument is the following discussion concerning to moral development in adolescence, where it is possible to observe the following difference of opinion between the teacher and a student (STU6M): according to the student, adolescents’ behaviors show to be very often more mature than adults’ ones, whilst the teacher clearly disagrees with her student’s opinion (line 3: “no::”) and puts forth an argument in support of her standpoint (line 5: “adolescence typically have more dangerous behaviors than adults”). In turn, the student advances a SCIENCE ARG (in Italic in the excerpt) that refers to the well-known Kohlberg’s theory of moral development in order to support his own opinion (line 6: “but Kohlberg said that adolescents can normally respect authority ad rules, and that’s pretty good”). This discussion will continue for several minutes, involving other students as well.

Excerpt 2

Lesson 4. Min. 59:50. Participants: teacher (TEACH), student (STU6M).

1. – *STU6M: adolescents’ behaviors are very often more mature than adults’ones

2. – %pau: 3.0 sec

3. – *TEACH: no::

4. – *STU6M: oh. yes professor ((laughing))

5. – *TEACH: adolescence typically have more dangerous behaviors than adults

6. – *STU6M: but Kohlberg said that adolescents can normally respect authority

ad rules, and that’s pretty good

7. – *TEACH: yes, but

[…]

5.2. Graduate Students’ Arguments

The analysis of the arguments put forth by the 16 graduate students involved the N= 43 argumentative discussions arisen around an issue related to the discipline taught in the course in which they put forward at least one argument to support their own standpoint, for a total number of N= 167 arguments. Unlike from what was observed for undergraduate students, the findings show that slightly more than half of the all arguments put forth by graduate students were SCIENCE ARG (N= 87; 52%). These arguments were used a little more frequently in student-teacher interactions (N= 46 out of N= 72 total arguments forth in interactions with their teacher) than in student to student interactions (N= 41 out of N= 95 total arguments put forth in interactions with their classmates).

In the following short example we can observe an argumentative discussion having as protagonists the teacher and one student, STU10F, occurred during a lesson centred on the development of identity and personality in adolescence. The teacher explains that adolescents face a phase in which they are committed to choose their values and goals for the future (line 1). The student shows to be in disagreement with the claim made by her teacher, and in turn advances a SCIENCE ARG in support of her opinion (in Italic in the excerpt) (line 2: “some adolescents decide not to choose, according to Marcia it’s the identity diffusion, they are not ready to take these decisions”). The discussion continues with the teacher that accepts the argument advanced by her student (line 3: “this is true, some of them don’t”) and reformulate her previous claim accordingly (line 4).

Excerpt 3

Lesson 6. Min. 32:15. Participants: teacher (TEACH), student (STU10F).

1. – *TEACH: during this phase ((adolescence)) they ((adolescents)) have to

decide their goals and values for their future

2. – *STU10F: some adolescents decide not to choose though, according to

Marcia it’s the identity diffusion, they are not ready to take these decisions

3. – *TEACH: this is true, some of them don’t

4. – *TEACH: they are supposed to choose their values and goals

[…]

As far as NO SCIENCE ARG are concerned, graduate students used these arguments more frequently during student to student interactions (N= 54 out of N= 95 total arguments put forth in student to student interactions) than during the interactions with their teacher (N= 26 out of N= 72 total arguments forth in student-teacher interactions). A clear example of the use of this type of argument is the following discussion, whose beginning is initially favoured by the teacher, about mental disorders in adolescence and the moment of their actual initiation. Here, it is possible to observe an argumentative discussions initially involving two students: STU15F and STU1F. According to the first student, the actual initiation of a mental disorder is before the manifestation, and she supports her opinion by advancing a NO SCIENCE ARG based on common sense knowledge (in Italic in the excerpt) (line 2: “you need to have a predisposition, because the genes produce a predisposition to have that:: it’s before the manifestation”). On the other hand, the second student claims that having a predisposition is fundamental only for certain mental disorders, not for all of them, since it can still go in multiple ways. In particular, she supports this claim by also advancing a NO SCIENCE ARG that is based on her own personal experience (in Italic in the excerpt) (line 3: “I know people who were depressed and now they are not”). This discussion will continue for several minutes, involving other students as well as the teacher.

Excerpt 4

Lesson 2. Min. 24:30. Participants: teacher (TEACH), students (STU15F; STU1F).

1. – *TEACH: when is an actual initiation of a ((mental)) disorder? is it when you

see some first symptoms or when you see the disorder, when is really labeled as a disorder?

2. – *STU15F: you need to have a predisposition, because the genes produce a

predisposition to have that:: it’s before the manifestation

3. – *STU1F: it’s different for disorders. even if you have a predisposition it can

still go in multiple ways. I know people who were depressed and now they are not

[…]

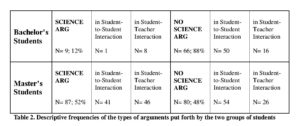

The presentation of different excerpts concerning the types of arguments used by the two groups (sub-corpus 1 and sub-corpus 2) of students shows an interesting element that can summarize the argumentative choices (and strategies) used by them with their classmates and with their teacher. The undergraduate students advance only rarely SCIENCE ARG (N= 9; 12%), and these arguments very used almost exclusively in student-teacher interactions. On the other hand, slightly more than half of the arguments put forth by graduate students were SCIENCE ARG (N= 87; 52%), which were used both in student-teacher interactions (N= 46) and in student-to-student interactions (N= 41). The NO SCIENCE ARG was instead the type of argument advanced in almost all cases by undergraduate students (N= 66; 88%), especially in student to student interactions (N= 50). The Table 2 shows a comparison between the types of arguments advanced by the two groups of students.

6. Discussion

The findings of this study appear to confirm the two initial hypotheses: 1) “undergraduate students draw their arguments from common sense and personal experience more often than graduate students”; and 2) “graduate students put forth arguments that refer to scientific notions and theories strictly or somehow related to the discipline taught in the course, i.e., Developmental Psychology, more often than undergraduate students”. How can we explain these results? Among the many reasons than can contribute at different degrees to explain these results, I want to focus on two aspects that I think are the most important.

The first reason is the actual students’ knowledge of the discipline taught in the course, i.e., Developmental Psychology. Even though the students of both groups – according to their own perception – seems to have a similar knowledge in Developmental Psychology, the observations of the topics treated during the lessons, of the student-teacher and student to student interactions, and the analysis of the arguments advanced by students has led me to realize that the graduate students had an actual knowledge of the discipline much higher than undergraduate students, even more than what was claimed in the answers to my short questionnaire (graduate students M= 7.25 vs. graduate students M= 6.35).

As we have seen in the excerpt 3, the graduate students showed to be able to use as an argument a limited, well-specific aspect of a scientific theory in order to support their own standpoint. Moreover, they were able to engage in critical discussions related to the different theories that treat certain limited aspects of a certain topic discussed during the lessons. On the other hand, the knowledge in Developmental Psychology of the undergraduate students was often limited to a more superficial knowledge of the discipline. In most cases, their SCIENCE ARG (N= 9) refer to a well-known theory, however avoiding to mention the correct term of the scientific notion they refer to. For example, in the excerpt 2 we have seen that a student advanced a SCIENCE ARG that refers to a well-known psychological theory, i.e., Kohlberg’s theory of moral development (Kohlberg, 1984), claiming that according to this theory adolescents can normally respect authority and rules. Evidently, the student is referring to the “stage four” of Kohlberg’s theory of moral development, however without mentioning it correctly.

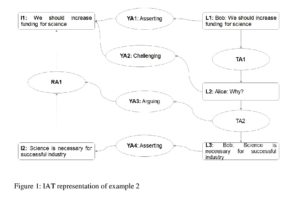

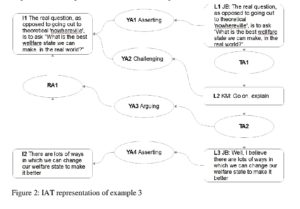

The second reason is related to the institutional commitment requested to the students. From the observations of student-teacher interactions, I noticed that an argumentative effort by students is requested only at the graduate level, not at the undergraduate one. Both at undergraduate and at graduate level, it is the teacher that in most cases favors the beginning of argumentative discussions in the classroom. She does it by asking questions to her students, inviting them to express their opinions, doubts about the theories and notions presented during the lesson. However, looking at the questions used by the teacher to favor the beginning of argumentative discussions, I observed some differences. At the undergraduate level, the teacher asks open questions to her students. These are questions can favor a large discussion with and among students, and they are not focused on limited, specific aspects of a theory, but instead these questions aim to favor a discussion around a more general topic. The focus of the discussion is not the single theory, but the more general topic. The following are good examples of these questions: What are the main reasons leading to episodes of bullying among adolescents? How can the family relationships affect the adolescent development? What are the consequences of adolescent drinking and substance use?

At the graduate level, instead, the teacher asks questions that refer to specific aspects of a certain theory. These questions are often followed by a further Why-questions asked to the students. Here, the students are expected to provide the reasons at the basis of their own opinions. The following are good examples of these questions: What are the most important processes that according to Steinberg explain the fact that many risk behaviors tend to peak in adolescence? … Why? Which developmental processes can be studied by each of the seven models described by Graber and Brooks-Gunn and how? … Why? What are the advantages and disadvantages of a person-centered approach? … Why?

Accordingly, it seems that at the undergraduate level students are (only) requested to be interested in and curious of the discipline taught in the course by asking questions. At the graduate level curiosity is not enough. Students are expected to support their standpoints – and even a mere doubt – by advancing arguments that have to refer to scientific theories.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) [grant number P2TIP1_148347].

References

Alexander, P. A., Kulikowich, J. M., & Schulze, S. K. (1994). The influence of topic knowledge, domain knowledge, and interest on the comprehension of scientific exposition. Learning and Individual Differences, 6(4), 379-397.

Alexopoulou, E., & Driver, R. (1996). Small-group discussion in physics: peer interaction modes in pairs and fours. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 33(10), 1099-1114.

Andrews, R. (2009). A case study of argumentation at undergraduate level in History. Argumentation. Special Issue on Argumentation and Education: Studies from England and Scandinavia, 23(4), 547-548.

Chin, C., & Osborne, J. (2010). Supporting argumentation through students’ questions: Case studies in science classrooms. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 19(2), 230-284.

Driver, R., Newton, P., & Osborne, J. (2000). Establishing the norms of scientific argumentation in classrooms. Science Education, 84(3), 287-312.

Duschl, R., Schweingruber, H., & Shouse, A., (2007). Taking science to school: Learning and teaching science in grades K-8. Washington, DC : National Academies Press.

van Eemeren F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies. A pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hatano, G., & Inagaki, K. (2003). When is conceptual change intended? A cognitive-sociocultural view. In G. M. Sinatra, & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Intentional conceptual change (pp. 407-427). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hogan, K., & Maglienti, M. (2001). Comparing the epistemological underpinnings of students and scientists reasoning about conclusions. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(6), 663–687.

Jiménez-Aleixandre, M. P., Rodriguez, A. B., & Duschl, R. A. (2000). ‘‘Doing the lesson’ or ‘‘Doing science’: Argument in high school genetics. Science Education, 84(6), 757–792.

Kelly, G. J., & Chen, C. (1999). The sound of music: Constructing science as sociocultural practices through oral and written discourse. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36(8), 883-915.

Kelly, G., & Takao, A. (2002). Epistemic levels in argument: An analysis of university oceanography students’ use of evidence in writing. Science Education, 86(3), 314–342.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The Psychology of Moral Development: Moral Stages and the Idea of Justice. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

Linn, M. C., & Eylon, B. S. (2006). Science education: Integrating views of learning and instruction. In P. A. Alexander, & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology (2nd ed.) (pp. 511–544). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Macagno, F., & Konstantinidou, A. (2013). What students’ arguments can tell us: Using argumentation schemes in science education. Argumentation, 27(3), 225-243.

Mason, L. (1996). Collaborative reasoning on self-generated analogies. Conceptual growth in understanding scientific phenomena. Educational Research and Evaluation, 2(4), 309-350.

Mason, L. (2001). Introducing talk and writing for conceptual change: a classroom study. Learning and Instruction, 11(6), 305-329.

McNeill, K. L., & Krajcik, J. (2009). Synergy between teacher practices and curricular scaffolds to support students in using domain specific and domain general knowledge in writing arguments to explain phenomena. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 18(3), 416-460.

Nussbaum, E. M., & Sinatra, G. M. (2003). Argument and conceptual engagement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28(3), 384-395.

Sadler, T. D. (2004). Informal reasoning regarding socioscientific issues: A critical review of research. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(5), 513-536.

Sadler, T. D., & Zeidler, D. L. (2005). The significance of content knowledge for informal reasoning regarding socioscientific issues: Applying genetics knowledge to genetic engineering issues. Science Education, 89(1), 71-93.

Sampson, V., & Clark, D. (2008). Assessment of the ways students generate arguments in science education: Current perspectives and recommendations for future directions. Science Education, 92(3), 447–472.

Sandoval, W. A., & Millwood, K. (2005). The quality of students’ use of evidence in written scientific explanations. Cognition and Instruction, 23(1), 23-55.

Sandoval, W. A., & Reiser, B. J. (2004). Explanation-driven inquiry: Integrating conceptual and epistemic scaffolds for scientific inquiry. Science Education, 88(3), 345-372.

Schwarz, B. B., Neuman, Y., & Biezuner, S. (2000). Two wrongs may make a right…if they argue! Cognition and Instruction, 18(4), 461-494.

von Aufschnaiter, C., Osborne, J., Erduran, J., & Simon, S. (2008), Arguing to learn and learning to argue: Case studies of how students’ argumentation relates to their scientific knowledge. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 45(1), 101-131.

Wiley, J., & Voss, J. F. (1999). Constructing arguments from multiple sources: tasks that promote understanding and not just memory for text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 301-311.