ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ A Formal Perspective On The Pragma-Dialectical Discussion Model

Abstract: For the development of computation tools to support the pragma-dialectical analysis of argumentative texts, a formal approximation of the pragma-dialectical ideal model of a critical discussion theory is required. A basic dialogue game for critical discussion is developed as the foundation for such formal approximation. To this basic dialogue game, which has a restricted complexity, the more complex features of critical discussion can gradually be added.

Keywords: computerisation, critical discussion, dialogue game, formalisation, pragma-dialectics.

1. Formalisation in preparation of computerisation

Formalisation is one of the important developments in the field of argumentation theory emphasised by van Eemeren in his keynote address at the 8th ISSA conference. My contribution to the ISSA conference deals with the formalisation of one theory of argumentation: the pragma-dialectical theory (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004; van Eemeren et al., 2014, pp. 517-613). This study is intended to contribute to a more encompassing research project, the overall goal of which is to create a formal foundation for a computational application of the pragma-dialectical theory.

The computational application of argumentation theory in general has developed into several directions, as is evident from, e.g., the overviews by Rahwan and Simari (2009) and van Eemeren et al. (2014, pp. 615-675). Instead of trying to formalise and computerise every possible application of the pragma-dialectical theory at once, the current aim is to create a foundation for computational tools to support the analysis of argumentative discourse. Although fully computerised pragma-dialectical analysis will presumably not be feasible for quite some time, smaller digital tools to assist human analysts in their analytical tasks can be realised on a shorter term.

One area in which such a smaller tool can offer support is the composition of the analytic overview. As the outcome of a (standard) pragma-dialectical analysis of an argumentative text, the analytic overview “brings together systematically everything that is relevant to the resolution of a difference of opinion” (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004, p. 118).[i] In order to arrive at an analytic overview, the analyst applies a two-step method. First, the ideal model of a critical discussion (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004, pp. 42-68) is used as a heuristic to determine which parts of the original text are (or can be considered as) argumentatively relevant. By applying four analytical transformation, the original text is reconstructed in terms of a critical discussion (van Eemeren et al., 1993, pp. 61-62). In the second step, an analytic overview is abstracted from this reconstruction. The composition of the analytic overview is fully determined by the content of the reconstruction in terms of a critical discussion. Based on the discussion moves made by discussants in the analytical reconstruction, the following is determined as part of the analytic overview: the nature of the difference of opinion, the distribution of discussion roles, the starting points, the arguments, the structure of the argumentation and the argument schemes (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004, pp. 118-119).

To develop a computational tool to support analysts in composing an analytic overview on the basis of a reconstruction of the original text in terms of a critical discussion, it is necessary to have a computational representation of the relations between the possible variations in the constitutive parts of the ideal model and those of the analytic overview. Preliminary to these relations, computational representations of the ideal model of a critical discussion, and of the analytic overview themselves are necessary. In the current paper a preparatory step towards the computational representation of the ideal model of a critical discussion is made by formalising part of the ideal model.

2. A formal approximation of critical discussion

The formal perspective on the pragma-dialectical ideal model is developed as a dialogue game. This dialogue game can be considered a formal approximation of the ideal model of a critical discussion. As an ‘approximation’, the dialogue game is not intended to replace the original model in any way – a conclusion that might inadvertently be drawn if it would be called a ‘formalisation’ proper. Additionally, the term ‘approximation’ indicates that it is unlikely that all features of the original ideal model can be preserved entirely in the formal dialogue game.

When a discrepancy between the original model and its formal counterpart occurs, this may in some cases indicate a flaw or imprecision in the original. In other cases it can be the result of the streamlining that is required to conform to the expressiveness of the formalism used. More often than not, a formalism is less expressive than a model expressed in natural language. One reason why this is so, is the requirement in formal models to explicitly and unambiguously define what is included, while excluding everything else. In this respect the formal approximation is stricter than the original ideal model.

The notion of a ‘formal approximation’ is analogous to that of an ‘empirical approximation’ of critical discussion introduced by van Eemeren and Houtlosser (2005). Empirical approximations are used in the extended pragma-dialectical theory (van Eemeren, 2010), where the focus is shifted from the idealised case of a critical discussion in the standard theory to studying the intricacies of argumentative discourse in everyday use. Unsurprisingly, interlocutors in ordinary discourse turn out not to behave exactly in accordance with an ideal model of communication. This does however not mean that they abandon all ideals entirely. For argumentative discourse, the ideal of reasonableness is a case in point.

To study the actual practice of argumentative discourse, the pragma-dialectical ideal model can be used as an analytic heuristic to make sense of the conventionalised communicative activities by seeing how they diverge from the ideal model. In this view, the ideal model is realised in terms of its empirical counterparts in ordinary communication. An actual argumentative exchange is then said to be an empirical approximation of the ideal model of a critical discussion.

Although it should be clear that an ideal model does not actually occur in communicative reality[ii] ‒ which is why actual argumentative discourse can merely be regarded empirical approximations ‒ it may not be so clear why an ideal model could not be formal. Indeed, Krabbe and others (Krabbe & Walton, 2011, p. 246; Krabbe, 2012, p. 12; van Eemeren et al., 2014, p. 304) have observed that the pragma-dialectical ideal model can already be said to be formal in the sense of being procedurally regimented (formal3 in Barth and Krabbe’s taxonomy (1982, pp. 14-19; Krabbe, 1982)) and a priori or normative (formal4). The formal approximation of critical discussion developed as a dialogue game, is intended to also be formal in the sense of rigorously specifying the linguistically well-formed expressions and the way in which these can be combined and used in a discussion (formal2).

3. Restricting the complexity of the model

The formal approximation of critical discussion is not developed all at once. Instead, a basic dialogue game is developed to which more complex features of the original ideal model can be gradually introduced. This systematic approach has the practical advantage of decomposing a larger task, so that the smaller components can be developed at different times or by different people. A second, theoretic advantage is that the gradual introduction of complex features provide insight into the model itself because its features can be studied in isolation, without other aspects complicating matters.

The basic dialogue game is developed to fulfil the role of the simplified basis to which more complexity can later be added. To lower the complexity of the dialogue game, three restrictions are in place with respect to the original ideal model, which the dialogue game is a formal approximation of. First, only the dialectical dimension of critical discussion is taken into account, disregarding the realisation of discussion moves in the ideal model through speech acts (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1984) and the rhetorical dimension of strategic manoeuvring (van Eemeren, 2010). Second, the dialogue game offers players fewer choices and opportunities compared to the original model. This restriction is most evident in the exclusion of complex argumentation, only allowing an arguer to put forward one single argument for his standpoint. Third, only the argumentation stage of critical discussion is explicitly part of the dialogue game, while of the other three discussion stages a specific (uncomplicating) outcome is assumed.

For the confrontation stage, the assumption is that a single positive standpoint was put forward, which met with doubt. This restricts the dialogue game to single non-mixed differences of opinion about a single positive standpoint, excluding differences of opinion about multiple standpoints or where a negative or opposing standpoint is assumed. The main restriction resulting from the assumed outcome of the opening stage is that only a single argument may be put forward, which may only be challenged by doubt, not by contradiction. Since the concluding stage only comes after the argumentation stage, no assumptions have to be made about that stage.[iii] The overall result of the assumed outcomes of the confrontation and opening stages is that the basic dialogue game developed in the next section is a formal approximation of the dialectical dimension of the argumentation stage of non-complex, consistently non-mixed critical discussions about one positive standpoint which is defended by appealing to a single justificatory reason.

4. A basic dialogue game for critical discussion

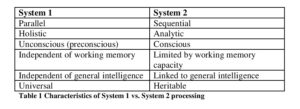

The dialogue game is introduced by means of five categories of rules. First, there are rules that determine the initial state of the game. Second, the moves that are available to the players are defined. Third, the effect of making moves on players’ commitments is made clear. Fourth, the sequential rules determine in which order moves may be made, sanctioning the structure of the dialogue. Fifth, there are rules specifying how the game ends; both when and in whose favour. The rules of the dialogue game are based on the 15 ‘technical’ rules of critical discussion (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004, pp. 135-157). These rules should not be confused with the ‘practical’ code of conduct consisting of 10 commandments for reasonable discussants (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992, pp. 208-209), which are based on the aforementioned 15 rules and are intended to be used as a rule of thumb in evaluating and conducting actual argumentative discussions. Due to the restrictions introduced in the preceding section, of the 15 rules, in particular rules 6-13 are relevant for the basic dialogue game.[iv]

In line with the ideal model, the basic dialogue game for critical discussion is played by two (teams of) players. The constitution of the players is left undetermined. In the ideal model the assumption is that the discussion parties are human interlocutors, but because the development of the dialogue game for critical discussion is intended to form a basis for pragma-dialectically oriented work in artificial settings, the nature of players of the game is left undefined. Eventually the dialogue game should be such that both human and artificial agents can play it.

How players internally represent the current and past states of the dialogue during the game and how they keep track of their own and the other player’s commitments is not a concern for the rules of the dialogue game. In the case of human players the internal make-up is a matter for cognitive psychology (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1984, p. 6), in the case of artificial agents, for software engineering. For the basic dialogue game it is sufficient to assume there to be some way of modelling the players. The rules of the dialogue game will not refer to, nor take into account, the individual modelling or private belief sets of the players.

A further aspect of the make-up of players which is not addressed in the rules for the dialogue game, is the matter of strategy. While playing the dialogue game, players have choices to make about their subsequent moves. Players can employ different strategies in playing the game to increase their chances of winning. Similar to the internal constitution of the players, their strategies are left undefined in the dialogue game rules. Rather, these strategies are taken to be part of the (‘subjective’ or ‘internal’) make-up (i.e. artificial modelling or psychological constitution) of the players.

The dialogue game rules assume there to be a formal language ℒ in which the propositions the game is about can be expressed. The nature of ℒ is not the object of the current study. It is therefore at present sufficient to take ℒ to consist of the sentences of propositional logic closed under the usual classical operators. All occurrences of φ or ψ in the rules refer to (atomic or molecular) propositions of ℒ.

A second (formal) system is required to represent the inferences appealed to by players in the dialogue game. Because the basic dialogue game is only intended as a simplified foundation, no assumptions are made about the particular reasoning system underpinning the inferences used in the game. The only requirement is that there is some external method of deciding the soundness of inferences. Although more elaborate systems (for example the pragma-dialectical account of argument schemes with critical questions (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992; Garssen, 1997), or non-monotonic systems of defeasible reasoning (e.g., Pollock, 1987; Dung, 1995) can be introduced as part of the gradual addition of complexity to the dialogue game, for the moment classical propositional logic can be taken to provide the inference rules applied by players in the dialogue game. Any reference to φ⇒ψ can then be interpreted as an appeal to a rule of inference from propositional logic on the basis of which the acceptability of φ justifies the acceptability of ψ.

4.1 Commencement rules

The commencement rules determine the initial state of the game before the first move has been made. Because both the confrontation and the opening stages of critical discussion are not explicitly modelled, the assumed outcomes of these stages are reflected in the initial state. With respect to the confrontation stage, the result is that the basic dialogue game for critical discussion is played by two players to determine the tenability of a positive standpoint with respect to some proposition ψ∈ℒ.

Based on the assumed outcome of the opening stage, the two players are designated Prot and Ant, corresponding to the discussion roles of protagonist and antagonist in (the argumentation stage of) a critical discussion. Prot is defending a positive standpoint with respect to ψ, while Ant critically assesses the defence, having doubt regarding the acceptability of ψ. Another outcome of the opening stage is the agreement upon a set of material and procedural starting points. In the dialogue game the material starting points are represented by a static set SP (for Starting Points) of propositions both players accept. Because the players need at least one common starting point to engage in a fruitful discussion (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004, p. 139), SP is assumed to be non-empty: SP ≠ ∅.[v] The procedural starting points are reflected in the following three assumptions: the players agree to play by the rules of the game; the players conform to a turn-based approach, where a player makes one of the moves defined in the next subsection after which the turn passes to the other player; the players have agreed upon an inferential system and a way to check the acceptability of instantiated inferences.

Finally, the purpose of the dialogue game is for the players to resolve their difference of opinion about ψ, where Prot will defend a positive standpoint with respect to ψ by providing argumentation supporting ψ and Ant critically tests ψ’s tenability by challenging the argumentation.

4.2 Move rules

Each turn one of the players makes one move. The moves made are of the form type(φ). The function the move fulfils in the context of the dialogue game is designated by type. The propositional content of the move is made up by either an (atomic or molecular) proposition φ∈ℒ, or the application of an inference rule (⇒) on a pair of propositions φ,ψ∈ℒ. Each unique instantiation of a move, i.e. the combination of a type and propositional content, can only be used as a move by a player once per game – in other words, a player may not repeat the exact same move he has already made before.

The basic dialogue game for critical discussion is asymmetrical with respect to the role the two players fulfil. Because of this, there are two separate sets of moves which are available to the two players of the game depending on their role. To defend his standpoint about ψ, Prot has the following moves available to him:

(M1) argue(φ): to present φ as an argument for ψ. (Note that φ≠ψ, to prevent circular reasoning).

(M2) identify(φ): to initiate the intersubjective identification procedure, in order to check the mutual acceptability of φ, here taken to be decidable by checking whether φ∈SP.

(M3) test(φ⇒ψ): to initiate the intersubjective testing procedure, in order to test the acceptability of the justificatory force of φ for ψ, assumed to be decidable through some external method, by determining whether φ⇒ψ is a sound instantiation of an inference rule.

(M4) retract(φ): to retract commitment to an argument, where φ∈CSProt.

(M5) conclusive_defence(ψ): to claim victory after a successful defence of a positive standpoint with respect to ψ.

To critically test Prot’s argumentation, Ant can make use of the following moves:

(M6) accept(φ): to accept φ in defence of ψ.

(M7) challenge(φ): to cast doubt on the material premise φ of an earlier move argue(φ).

(M8) challenge(φ⇒ψ): to cast doubt on the justificatory force φ⇒ψ of an earlier move argue(φ).

(M9) successful_attack(φ): to claim the successful challenging of the acceptability of φ.

(M10) successful_attack(φ⇒ψ): to claim the successful challenging of the acceptability of φ⇒ψ.

(M11) conclusive_attack(ψ): to claim victory after a successful criticism of Prot’s argumentative defence of ψ.

4.3 Commitment rules

As a result of making moves, players acquire (and retract) commitments. These commitments are called ‘dialectical’, referring to their dialectical function in a discussion, and are conceived of in line with Hamblin’s (1970) conception. If a player is committed to a certain proposition, this means he should be prepared (or is even obliged) to defend the acceptability of the proposition if prompted to do so, in other words he assumes a potential burden of proof.[vi]

Both players are associated with an individual commitment store in which the propositions a player is committed to in the dialogue are kept track of. A player’s commitment store is represented by a set of propositions, which is publicly readable (meaning that it is available for all players) and privately writeable (meaning that a player can only directly update his own commitment store, not that of the other player). At the start of the game, the players’ commitment stores are filled with some propositions. Based on the requirements at the start of the game, Prot’s commitment store contains the common starting points and the standpoint ψ,[vii] while Ant’s commitment store only contains the common starting points. It is important to note that the respective commitment stores may contain additional propositions than those mentioned here, so long as ψ∉CSAnt – otherwise Ant would also be committed to the standpoint before starting the game, so that no difference of opinion would arise in the first place. Before any moves are made, the players’ commitment stores are as follows:

(C1) CSProt = SP ∪ {ψ}.

(C2) CSAnt = SP.

As a result of moves during the game, these commitment stores can be updated. The performance of some moves results in the acquisition of new commitments, while other moves retract commitments. There are three moves in the basic dialogue game for critical disussion that result in an update of the player’s commitment store (with the affected commitment store before the equals sign, and the resulting updated commitment store after it):

(C3) argue(φ): CSProt = CSProt ∪ {φ, φ⇒ψ}.

(C4) retract(φ): CSProt = CSProt ‒ {φ, φ⇒ψ}.

(C5) accept(φ): CSAnt = CSAnt ∪ {φ, φ⇒ψ}.

4.4 Sequential rules

The preceding two subsections presented respectively which moves there are in the basic dialogue game for critical discussion and what the effect is of making these moves in terms of the players’ commitments. The sequential rules introduced in this subsection define when moves can be made. The dialogue game is always started by Prot making a move argue(φ) to put forward φ in defence of the standpoint at issue, ψ. At which moments the other moves can legally be made is dependent on the state of the game at that moment. The relevant aspects of the state of the game in this respect are the move made by the other player in the preceding turn, and in some cases the content of the commitment stores of the players. This results in the following rules:

(S1) argue(φ): starting move, if ψ is argued for, then φ≠ψ.

(S2) identify(φ): may follow challenge(φ), where φ represents an argument’s propositional content.

(S3) test(φ⇒ψ): may follow challenge(φ⇒ψ), where φ⇒ψ represents an argument’s justificatory force.

(S4) retract(φ): may follow challenge(φ), challenge(φ⇒ψ), successful_attack(φ), or successful_attack(φ⇒ψ)[viii].

(S5) conclusive_defence(ψ): follows accept(φ).

(S6) accept(φ): may follow identify(φ) if φ∈SP, test(φ⇒ψ) if φ⇒ψ is sound, or argue(φ).

(S7) challenge(φ): may follow argue(φ), or test(φ⇒ψ) if φ⇒ψ is sound.

(S8) challenge(φ⇒ψ): may follow argue(φ), or identify(φ) if φ∈SP.

(S9) successful_attack(φ): follows identify(φ) if φ∉SP.

(S10) successful_attack(φ⇒ψ): follows test(φ⇒ψ) if φ⇒ψ is not sound.

(S11) conclusive_attack(ψ): follows retract(φ).

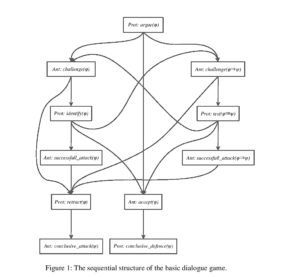

To clarify the sequential structure of the basic dialogue game, I present Figure 1 as a visualisation of the sanctioned sequences in terms of a tree. The nodes of the tree are the moves of the dialogue game (with the format [Player: type(propositional content)] and the arrows indicate the possible transitions between moves (from one turn to the next).[ix] The node at the top of Figure 1 denotes the start of the game, i.e. the first move. The dialogue game terminates at one of the two nodes at the bottom of Figure 1. The route straight through the middle of the tree is the shortest route where Ant immediately accepts the argument. In the left and right routes, the acceptability of, respectively, the propositional content and the justificatory force of the argument are challenged.

4.5 Termination rules

The concluding stage is not explicitly incorporated in the basic dialogue game for critical discussion. It is nevertheless clear that the winning or losing of the dialogue game can be based on the outcome discussants can obtain in the argumentation stage of the ideal model. The dialogue game terminates if one of the players performs the move conclusive_attack(ψ) or conclusive_defence(ψ). Once the game has stopped in this way, the winner is Prot if φ∈CSAnt, (corresponding to the case where the antagonist accepts φ as an argument in defence of ψ) and Ant otherwise.[x]

5. Conclusion

I began this paper by discussing the role the basic dialogue game for critical discussion plays in a more encompassing research project. The aim of this project is to lay a formal foundation for the development of digital tools to aid the pragma-dialectical analysis of argumentative discourse. To constrain the scope of the project, the current focus is on tools to computerise the abstraction of an analytic overview from a reconstruction of a text in terms of a critical discussion. In preparation of the development of such an analytical tool, a formal approximation of the ideal model of a critical discussion is necessary, together with the relation between this formal approximation and the elements of an analytic overview.

The formal approximation is started in this paper with a basic dialogue game for critical discussion. The game is defined in terms of rules for commencement, moves, commitments, sequences and termination. By following the rules of the basic dialogue game, two players can play a game by entering in a simple dialogue. One of the players presents an argument in defence of a standpoint that has not been mutually accepted. The other player can respond by challenging the propositional content or justificatory force of the argumentation, or by accepting it. A challenge can be parried by initiating the relevant intersubjective procedure to check the acceptability, or can be followed by a retraction of the argumentation. Depending on the outcomes of the intersubjective procedures and the acceptance or retraction of the argumentation, one of the two players wins the game.

Even though it is obvious from this simple characterisation that there is not much inherent value in the basic dialogue game as a playable game, it does however serve a purpose as a foundation for future work. This goal required the dialogue game to be relatively easy to develop and understand, so that formal approximations of more complex features of the ideal model can be modelled on the basis of this simplified dialogue game, and their effect be investigated systematically and in isolation.

Acknowledgements

This paper builds on continued discussions and prior work with Frans van Eemeren, Francisca Snoeck Henkemans, Bart Garssen, Floris Bex, and Chris Reed. I am grateful for their suggestions and collaboration.

References

Barth, E. M., Krabbe, E. C. W. (1982). From axiom to dialogue: A philosophical study of logics and argumentation. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Dung, P. M. (1995). On the acceptability of arguments and its fundamental role in nonmonotonic reasoning, logic programming and n-person games. Artificial Intelligence, 77(2), 321-357.

van Eemeren, F. H. (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse: Extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

van Eemeren, F. H., Garssen, B., Krabbe, E. C. W., Snoeck Henkemans, A. F., Verheij, B., & Wagemans, J. H. M. (2014). Handbook of argumentation theory. Amsterdam, etc.: Springer

van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (1984). Speech acts in argumentative discussions: A theoretical model for the analysis of discussions directed towards solving conflicts of opinion. Dordrecht: Foris.

van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies: A pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Eemeren, F. H., Grootendorst, R., Jackson, S., & Jacobs, S. (1993). Reconstructing argumentative discourse. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press.

van Eemeren, F. H., & Houtlosser, P. (2005). Theoretical construction and argumentative reality: An analytic model of critical discussion and conventionalised types of argumentative activity. In D. Hitchcock & D. Farr (Eds.), The uses of argument. Proceedings of a conference at McMaster University, 18-21 May 2005 (pp. 75-84). Hamilton, ON: OSSA

van Eemeren, F. H., Houtlosser, P., & Snoeck Henkemans, A. F. (2007). Argumentative indicators in discourse. Dordrecht: Springer.

Garssen, B. (1997). Argumentatieschema’s in pragma-dialectisch perspectief [Argument schemes in pragma-dialectical perspective]. Amsterdam: IFOTT.

Garssen, B. (2009). Book review of Dialog theory for critical argumentation by Douglas N. Walton (2007). Journal of Pragmatics, 41, 186-188.

Hamblin, C. L. (1970). Fallacies. 1970. London: Methuen.

Houtlosser, P. (1995). Standpunten in een kritische discussie [Standpoints in a critical discussion]. Amsterdam: IFOTT.

Krabbe, E. C. W. (1982). Studies in dialogical logic. (Doctoral dissertation). Groningen University.

Krabbe, E. C. W. (2012). Formal dialectic: From Aristotle to pragma-dialectics, and beyond. In B. Verheij, S. Szeider& S. Woltran (Eds.), Computational models of argument. Proceedings of COMMA 2012. Amsterdam, etc.: IOS Press

Krabbe, E. C. W., & Walton, D. N. (2011). Formal dialectical systems and their uses in the study of argumentation. In E. Feteris, B. Garssen & F. Snoeck Henkemans (Eds.), Keeping in touch with Pragma-Dialectics (pp. 245-263). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lewiński, M. (2010). Internet political discussion forums as an argumentative activity type. Amsterdam: SicSat.

Pollock, J. (1987). Defeasible reasoning. Cognitive Science, 11, 481-518.

Rahwan, I., & Simari, G. R. (Eds.). (2009). Argumentation in artificial intelligence. Dordrecht: Springer.

Visser, J.C. (2013). A formal account of complex argumentation in a critical discussion. In D. Mohammed & M. Lewiński (Eds.), Virtues of Argumentation. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (OSSA), 22-26 May 2013 (pp. 1-14). Windsor, ON: OSSA.

Visser, J., Bex, F., Reed, C. & Garssen, B. (2011). Correspondence between the pragma-dialectical discussion model and the argument interchange format. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 23(36), 189-224.