ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ Classifying Argumentation/Reasoning Schemes Proper Within The New Rhetoric Project

Abstract: Previous research on the New Rhetoric Project’s classification categories for argumentation/reasoning schemes has dismissed three overarching categories – association, dissociation, and breaking of connecting links, and focused on specific schemes proper. Challenging this communal understanding of the Project about the classification of schemes proper, this article will reconfigure the relationship between the overarching categories and schemes proper. In this process, a forth overarching category, or ‘re-confirming of connecting links’ will be proposed and defended.

Keywords: adherence, argumentation/reasoning schemes proper, association, audience, breaking of connecting links, dissociation, New Rhetoric Project (NRP), and re-configuring of connecting links

1. Introduction

Since Arthur Hastings’ dissertation on mode of reasoning was re-discovered in mid-1980s, research on argumentation/reasoning schemes[i] has flourished. Pragma-Dialecticians, rhetoricians, informal logicians, and computer scientists have written on the topic, which has helped argumentation schemes to gain presence within the community of argumentation scholars.

Before the research on argumentation schemes became significant, Chaim Perelman and Lucie-Olbrechts Tyteca examined various schemes/techniques of argumentation in their New Rhetoric Project (NRP). In classifying argumentation schemes proper, the NRP offers three overarching categories: association, dissociation, and breaking of connecting links. With association, arguers assemble entities that are thought to be different into a single unity, using techniques such as quasi-logical arguments, arguments based on the structure of the real, and arguments establishing the structure of the real. Each of these subcategories have their sub-subcategories under which specific argumentation schemes proper, such as argument from sign, analogical argument, or causal argument are discussed.

With dissociation, arguers dissemble what is originally thought to be a single unified entity into two or more different entities by introducing criteria for differentiation. Using dissociation, they help their audience members see the situation in a new light and attempt to persuade them to accept it. In short, dissociation attempts to establish a conceptual distinction and a hierarchy within what is believed to be a single and united entity.

In discussing dissociation, the NRP briefly refers to breaking of connecting links as a third category. This third category is referred to as opposition to the establishment of the connection, interdependence, or unity constructed by association.

In the first three chapters we examined connecting links in argumentation that have the effect of making interdependent elements that could originally be considered independent. Opposition to the establishment of such an interdependence will be displayed by a refusal to recognize the existence of a connecting link. Objection will, in particular, take the form of showing that a link considered to have been accepted, or one that was assumed or hoped for, does not exist, because there are no grounds for stating or maintaining that certain phenomena under consideration exercise an influence on those which are under discussion and it is consequently irrelevant to take the former into account. (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, p. 411)

In the breaking of connecting links, audience members mistakenly accept or assume that a key entity in the premise constitutes one and the same unity at the beginning of argumentation when it is actually made up of distinctively different entities; the inferential process reveals the audience members’ confusion and advances the thesis that reveals the distinction that exists. Forcing the audience members to recognize their confusion and understand the lack of connection can be substantiated “by actual or mental experience, by changes in the conditions governing a situation, and, more particularly, in the sciences, by the examination of certain variables” (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, p. 411).

While the NRP does not claim to be exhaustive in its treatment of argumentation schemes, the three categories seem to be general enough to encompass different scheme types. However, argumentation scholars have criticized its weaknesses (Eemeren, Garssen, Krabbe, Henkemans, Verheij, and Wagemans, 2014, pp. 291-292; Kienpointner, 1987, p. 39). A strong criticism against the NRP on its treatment of argumentation schemes proper comes from Kienpointner. He states that:

(T)he same scheme can be seen as means of association and dissociation, or with other words, means of justification and refutation. As most dissociative pairs correspond to associative schemes (which correspond on their turn to the types of warrants of the standard catalogue), I content myself to present the associative schemes. (Kienpointner, 1987, p. 283)

With this line of criticism he denies the necessity of the overarching categories of association, dissociation, and breaking of connecting links. Instead, he examines only argumentation schemes proper used for association, disregarding ones used for dissociation. Since his criticism denies the need for the triad categories and urges us to focus only on argumentation schemes proper, it constitutes a serious challenge to the NRP’s classification of argumentation. Therefore, it calls for our investigation.

In light of Kienpointner’s strong criticism, this article will attempt to inquire into the overarching categories of argumentation proposed by the NRP and redeem its treatment of argumentation schemes. Four key issues to be discussed in this article are as follows:

(1) How clear are the NRP’s overarching categories to classify argumentation schemes, based on association, dissociation, and breaking of connecting links?

(2) How are three overarching categories and argumentation schemes proper related to each other?

(3) How good are previous secondary research works on the NRP on its treatment of argumentation schemes by Kienpointner, Gross and Dearin, and Warnick and her colleagues?

(4) How comprehensive are the three overarching categories to classify argumentation schemes? In the following sections, this article will examine these key issues in this order for better situating the NRP’s approach to classify argumentation schemes proper within the current research on argumentation schemes, while keeping consistent with the spirit of the Project.

2. How clear are the NRP’s overcarching categories to classify argumentation schemes?

Kienpointner claims that there is no need for the classification categories based on association and dissociation because one and the same scheme can be used both with association and dissociation. For this reason he has dismissed dissociative schemes and focused only on associative schemes. Although he does not support his thesis against the NRP, actual texts of the NRP support his thesis. When discussing incompatibility as an instance of association, Perelman explicitly states that:

if we want to resolve an incompatibility and not just put it off, we must sacrifice one of the two conflicting rules, or at least ‘recast’ the incompatibility by a dissociation of ideas. (Perelman, 1982, p. 61).

Besides, when he discusses implicit dissociation, he refers to tautology – another instance of association.

A writer does not have to make explicit reference to a philosophical pair or one of its terms for the reader to introduce a dissociation spontaneously, when faced with a text that would be incoherent and tautological, and hence insignificant, without it. (Perelman, 1982, p. 135).

Furthermore, Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca state that “it is possible to interpret any analogy can be interpreted as dissociation” although they assign sections for analyzing analogy under association” (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, p. 429). Since Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca admit that these argumentation schemes proper can be used both with association and dissociation, Kienpointner rightly observes that there is some vagueness in the NRP’s classificatory system of argumentation schemes. From the textual support for the thesis advanced by Kienpointner, we must, at least, accept part of his thesis that one and the same scheme proper can be used with association and dissociation. Although it must be examined whether the association-dissociation categories are necessary, suffice it to say that the NRP is vague in its development of classifying argumentation schemes proper.

3. How are three overarching categories and schemes proper related to each other?

Kienpointner’s criticism exposes some weaknesses in the NRP’s classification categories for argumentation schemes proper. However, those categories can be coherently coordinated with schemes proper with a more careful scrutiny of the NRP. This article argues that the three classification categories (association, dissociation, and breaking of connecting links) are different from schemes proper, so it is a category mistake to reduce the former to the latter and examine only associative argumentation schemes.

For us to better understand the overarching categories, we must first revisit the aim of argumentation and the internal structure of a unit of argument as defined by the NRP. In discussing non-formal argumentative discourse, Perelman states as follows:

The purpose of the discourse in general is to bring the audience to the conclusions offered by the orator, starting from premises that they already accept – which is the case unless the orator has been guilty of a petitio principi. The argumentative process consists in establishing a link by which acceptance, or adherence, is passed from one element to another…, and this can be reached either by leaving the various elements of the discourse unchanged and associated as they are or by making a dissociation of ideas. (Perelman, 1979, pp. 18-19)

This short passage emphasizes that argumentation is conducted for increasing adherence of audience members to the thesis/conclusion of arguments. An argument starts with premises that audience members accept, then bring them to the conclusion with the assistance of the argumentative process. This argumentative process is also called schemes or techniques of argumentation in the NRP, and association and dissociation are extensively discussed, with breaking of connecting links being concisely described.

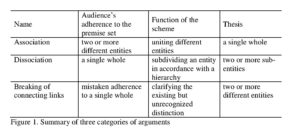

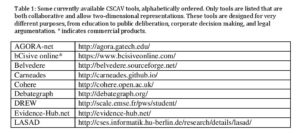

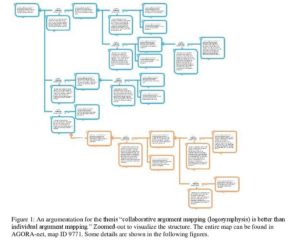

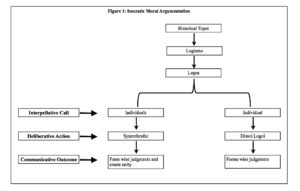

While Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s descriptions of these three categories are fuzzy, they informs us of key nature of rhetorical arguments. These three categories draw on audience members’ adherence as a general principle and classify premises and theses, as well as argumentation schemes. They classify types of premise and inform us whether audience members rightly or mistakenly regard key entities in the premise as unified or different, how the inferential process transforms their adherence or corrects their confusion, and whether the thesis establishes or clarifies a unity or a division. Since the three categories go beyond the inferential process and also cover audience members’ adherence to both premise and thesis, none of the three categories are identified with or reduced to argumentation schemes proper. Instead, they inform us of the functions that each of the constituent parts of an argument serve in transforming audience members’ adherence or correcting their confusion. From the roles that the three categories play in classifying the constituent parts of the argument and informing their functions, we can presume that the categories are relevant to and shed light on argumentation schemes proper, although that they feature a wider scope than argumentation schemes proper. The three categories function as umbrella terms that inform us of the function of the constituent parts of the argument in terms of the audience. However, it would be a mistake to reduce them to argumentation schemes proper, for they are just as relevant to argumentation schemes as they are to premises and theses. Figure 1 summarizes specific features of association, dissociation, and breaking of connecting links in light of the three components of arguments:

4. How good are previous secondary research works on the NRP’s treatment of argumentation schemes?

Based on the theses advanced in the previous sectiona, the previous research on the NRP’s approach to argumentation schemes proper seems to commit categorical mistakes. This section of the article will examine some of the previous research that has dealt with the NRP’s treatment of argumentation schemes.

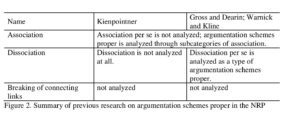

As the previous section of this article has revealed, Kienpointner has rightly understood that one scheme can be used with association and dissociation. However, his dismissal of dissociation and breaking of connecting links and his exclusive focus on (sub-)subcategories of association fail to account for the roles that association, dissociation, and breaking of connecting links play in modifying audience members’ adherence to the premise and linking it to the thesis. Additionally, he fails to advance our understanding of the relationships between the three-partite categories and argumentation schemes proper. While it is possible to advance our understanding of argumentation schemes proper without referring to the three-partite classification categories as Kienpointner has done, the role and the significance of the audience members’ adherence become much more evident when we relate argumentation schemes proper to the overarching categories. Argumentation schemes proper generally lead the audience members to adhere to the thesis based on the acceptable premise. Still, the three-partite categories tell us more about how the audience members’ adherence is transferred from the premise to the thesis by resorting to a particular argumentation scheme proper. Given the central role that the audience plays in the NRP, Kienpointner’s dismissal inadequately recaptures the role of argumentation schemes in the Project at the theoretical level. At the practical level, his dismissal may end in insufficient incorporation of the conception of audience in analysis and appraisal of argumentative texts. As a research program aiming to advance our understanding on argumentation schemes proper, Kienpointner’s approach, which focuses only on argumentation schemes proper, is reasonable. However, as a research program aiming to grasp argumentation schemes proper within a theoretical framework emphasizing the role of the audience, his scope is too narrow to be comprehensive on theoretical or practical grounds. Therefore, while he seems to have rightly observed the relationships between the classification categories based on association, dissociation, and breaking of connecting links and argumentation schemes proper, his dismissal of the classification categories is off the mark in light of the NRP’s emphasis on audience. To put it simply, Kienpointner is not rhetorical enough in dealing with argumentation schemes proper.

While Kienpointner has dismissed dissociative arguments, Gross and Dearin, and Warnick and Kline have mistakenly treated dissociation per se as an argumentation scheme proper. However, they do not discuss association per se as an argumentation scheme proper. Instead, they discuss (sub-)subcategories of association as argumentation schemes proper. For example, Gross and Dearin assign one chapter to each of quasi-logical arguments, arguments from the structure of reality, arguments establishing the structure of reality, and dissociation (Gross and Dearin, 2003, pp. 43-97). Warnick and Kline set up a similar classification categories and discussed thirteen argumentation schemes proper, which includes dissociation per se. In both cases, while dissociation per se is treated as an argumentation schemes proper, association per se is not examined at all, so we are at a loss why or in what respect association is necessary in the classification of argumentation schemes. Furthermore, these scholars do not consider Kienpointner’s criticism and fail to account for (sub-)subcategories of association used with dissociation, such as incompatibility, tautology, or analogy.

Example (1) below shows that a so-called associative argumentation scheme is used with dissociation, thereby questioning the line of research pursued by Gross and Dearin, and Warnick and Kline. Toshisada Takada, a Japanese military officer stationing on the Amami Islands in Japan (to the north of Okinawa Prefecture) at the end of WWII, was demanded to sign a disarmament document. He used dissociation based on argument from consequence and denied signing the document unless it was revised.

(1)

Premise: The U.S. Tenth Army adheres to the understanding that the Amami Islands are Northern Ryukyu.

Scheme: While the Amami Islands can historically be regarded as Northern Ryukyu, they ought to be viewed as part of Kagoshima Prefecture for the purpose of carrying out disarmament of the Japanese Army stationed on the Amami Islands.

Thesis: The Amami Islands are classified as part of Kagoshima Prefecture, rather than Northern Ryukyu. (adapted from Takada, 1965, pp. 96-97)

In his attempt to counter the adherence by the US Tenth Army that was in charge of the negotiation, Takada introduces two ways to understand the Amami Islands: historical and administrative. Administratively, the Amami Islands had been part of Kagoshima Prefecture from the second half of the 19th century through to the end of World War II. This position is opposed to the American position that links the Amami Islands to Ryukyu, an old name for Okinawa Prefecture. By emphasizing his own understanding of geographical and historical conditions of the Islands, Takada discredits the American interpretation in light of the goal of the argumentative situation. Since the disarmament of the Japanese Army is the goal of the argumentative exchange between Takada and the U.S. Tenth Army, the historical perspective associating the Amami Islands with Northern Ryukyu is unconvincing to Takada and the Japanese Army. In contrast, the administrative perspective would lead to the desired end of disarming the Japanese Army in the area. This way, the Amami-as-Kagoshima thesis is more cogent than the Amami-as-Ryukyu thesis in this particular argumentative situation because of the potential consequences the former would likely bring about. In other words, the scheme used in this instance is pragmatic argument, or argument from the consequence, which is classified as a type of arguments based on the structure of reality. This dissociative argument confirms Kienpointner’s criticism that one scheme can be used with association and dissociation. It also confirms the author’s position that association, dissociation, and breaking of connecting links are overarching categories to classify argumentation schemes proper, rather than schemes proper per se.

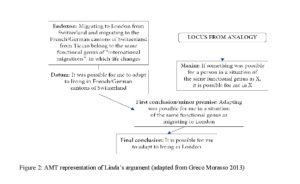

In summary, Kienpointner’s criticism against the NRP makes sense, but his research does not account for the overall picture of the three-partite categories in light of the audience. Gross and Dearin, and Warnick and Kline commit a categorical mistake and do not fully account for association per se and roles that argumentation schemes proper plays in dissociative arguments. Figure 2 summarizes what the previous scholarship by Kienpointner, Gross and Dearin, and Warnick and Kline.

5. How comprehensive are the three overarching categories to classify argumentation schemes proper?

The NRP has not claimed exhaustiveness in its treatment of argumentation schemes proper. However, for making the overarching categories more comprehensive, this article argues that there should be a fourth overarching category to classify argumentation schemes proper. Since this fourth type forces the audience members to recognize already-existing connecting links, it is called ‘re-confirming of connecting links.’ The argument for the existence of the fourth category hinges on the nature of breaking of connecting links and its relation to dissociation; therefore this article initially deals with the relationship between breaking of connecting links and dissociation, then that between dissociation and association.

The NRP has repeatedly emphasized that association and dissociation are two main categories and concisely described breaking of connecting links. In those concise descriptions, the NRP has consistently dealt with breaking of connecting links in contrast with dissociation. It is characterized as opposition to establishing associations or as techniques clarifying the existing divisions in the entities dealt in the premises of arguments. In other words, arguers make use of breaking of connecting links to force the audience members to accept that they fail to recognize the existing division.

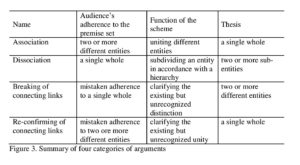

While the NRP treats association and dissociation extensively, only dissociation has a complementary category called breaking of connecting links. If association is actually the other main category, then it must have same or similar qualifications, because two entities sharing essential characteristics must be treated in the same manner, according to the rule of justice that the NRP endorses. The NRP does not offer reasoning contrary to this speculative position. Therefore, we can presume that association must have a complementary pair including association and something else. Here comes the need for a fourth category of arguments.

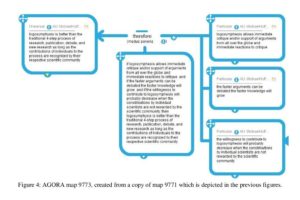

Because the fourth category, or “re-confirming of connecting links” forces the audience members to recognize their mistaken adherence to the entities dealt with in the premise set, it is to association what breaking of connecting links to dissociation. In this fourth category of argument, audience members mistakenly accept or assume that premises constitute different entities when they actually constitute a single whole. The inferential process reveals the audience members’ mistaken adherence and advances the thesis, revealing the unity that actually exists but goes unnoticed by the audience.

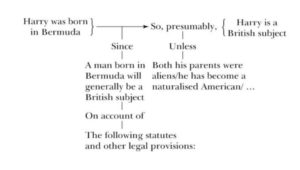

As the dissociation starts with audience members’ adherence that the premise constitutes a single whole, the association starts with their adherence that the premise is composed of different entities. In contrast, the re-confirming of connecting links starts with their mistaken adherence that the premise is composed of different entities, although it actually constitutes a single whole. The inferential process of the association combines those different entities into a single whole, whereas that of the re-confirming of connecting links clarifies their mistaken adherence and forces them to understand that the premise set originally constitutes a single whole. The thesis of the association presents a single whole as a result of the inferential process, whereas that of the re-confirming of connecting links presents the originally existing single whole in a clearer manner. In other words, while the association transforms the audience members’ adherence to the premise by bringing separate entities together, the re-confirming of connecting links corrects their mistaken adherence to the premise by having them understand that they have confused a single entity with separate entities as the starting point of the argument. In conclusion, while the NRP focuses on the association and the dissociation as two main categories of argument and briefly discusses the breaking of connecting links, the existence of the re-confirming of connecting links is logically implied by these three categories, according to the rule of justice. With re-confirming of connecting links being added to the existing three categories, the NRP’s categories of arguments are summarized in figure 3:

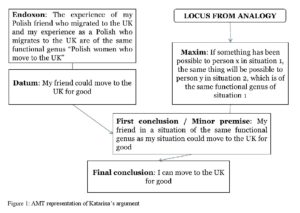

Having speculatively argued for the existence of the fourth category, the onus is on the author to substantiate the thesis being advanced. In the following self-deliberation arguments, Haruki Murakami, a well-known Japanese novelist, argued with himself about whether a Aum Shinrikyo’s sarin gas attack victim suffered from different types of violence from Aum Shinrikyo and the company he worked for. He was forced to quit after the gas attack because he could not perform well due to the aftereffect of the attack.

(2)

Premise: A victim of the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system suffered from excessive violence twice.

Scheme: The excessive violence can be subdivided into the violence of an abnormal society, Aum Shinrikyo and that of normal society, a company, with normal society being more regular and reasonable than the abnormal.

Thesis: The violence by Aum Shinrikyo is more deserving of condemnation than that by the company.

(3)

Premise: The two types of excessive violence seem to emerge from the same root.

Suppressed Scheme: The same root must have caused two different types of violence.

Thesis: The distinction between the two types of excessive violence are not persuasive to the victim of both. (Adapted from Murakami, 2001, pp. 3-4)[ii]

In example (2), Murakami attempts to dissociate different types of violence based on where the two violent acts come from. In example (3), however, he corrects his own thinking that the violent acts are two different entities. By directing his attention to the same metaphorical roots of the acts, he concludes that the two acts are the same. Since he makes himself recognize the unrecognized unity among the violent acts, it is an instance of re-confirming of connecting links. With the quality of these arguments being set aside, example (3) is a clear instantiation of re-confirming of connecting links.

6. Conclusion

In this article, the author has extended Kienpointner’s criticism against the NRP’s treatment of argumentation schemes proper. First, this article has acknowledged his criticism that the NRP is not clear about its classification framework of argumentation schemes proper. Next, this article has clarified the relationship between the overarching classification categories of argument (association, dissociation, breaking of connecting links and re-confirming of connecting links) and argumentation schemes proper, concluding that the former cannot be reduced to the latter. In light of this theoretical discussion, this article has critiqued previous secondary research on argumentation schemes proper from a NRP’s point of view, because it fails to account for the significance of the audience or distinguish the overarching categories from argumentation schemes proper. Finally, this article has added re-confirming of connecting links to the existing overarching categories based on the rule of justice that the NRP endorses. While the author admits that further case studies are needed to substantiate all the claims advanced in this article, this article has made a presumptively cogent case on how to classify argumentation schemes in accordance with the NRP.

Topics that merit further inquiries concerning the NRP’s treatment of argumentation schemes include (1) compilation of specific argumentation schemes proper used in dissociation, breaking of connecting links and re-confirming of connecting links, and (2) development of an approach to argument evaluation and criticism that incorporates audience. The first research topic is geared more toward empirical, and the second one is geared toward theoretical as well as empirical. As has been recently discussed by Johnson (2013) and Tindale (2013), the notion of audience calls for theoretical development as well as empirical substantiation. While there is no doubt that audience must play the central role in New Rhetorical theories of argumentation, discussion has been going on about how to crystallize the notion of audience although there has been no consensus (Crosswhite, 1996; Gross and Dearin, 2003; Jorgensen, 2009; Tindale, 1999, 2004). Discussing audience at the theoretical level through substantive evidence, we can hopefully refine our views on this challenging construct, thereby enriching the field of rhetorical argumentation.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on the author’s dissertation at University of Pittsburgh. I thank Gordon Mitchell, John Lyne, E. Johanna Hartelius, Nicholas Rescher, and Merrilee H. Salmon for their guidance and support.

NOTES

i. While many scholars use ‘argumentation scheme’ as a key phrase, the author follows J. Anthony Blair’s position that schemes are predicated of reasoning (mental act of inferring) and argument (social speech act between parties) (Blair, 2001, pp. 372-373). This position is consistent with the New Rhetoric Project that considers self-deliberation (internal argumentation with arguers themselves) is an variation of argumentation with others.

ii. Since English translation of Murakami’s work omits some text, the author has referred to both English and Japanese edition.

References

Blair, J. A. (2001). Walton’s argumentation schemes for presumptive reasoning: A critique and development. Argumentation 15, 365-379.

Crosswhite, J. (1996). The rhetoric of reason: Writing and the attractions of argument. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Garssen, B., Henkemans, A. F. S., Verheij, B., & Wagemans, J. H. M. (2014). Handbook of argumentation theory. Dordrecht, Netherlands.

Gross, A. G. & Dearin, R. D. (2003). Chaim Perelman. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Johnson, R. H. (2013). The role of audience in argumentation from the perspective of informal logic. Philosophy and Rhetoric 46.4, 533-549.

Jorgensen, C. (2009). Interpreting Perelman’s universal audience: Gross versus Crosswhite. Argumentation 23, 11-19.

Kienpointner, M. (1987). Towards a typology of argumentative schemes. In Frans H. van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, J. Anthony Blair, and Charles A. Willard (Eds.), Argumentation: Across the lines of discipline (pp. 275-287). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Murakami, H. (1999). Underground, Paperback ed. Tokyo: Kodansha.

Murakami, H. (2001). Underground. Translated by Alfred Birnbaum and Philip Gabriel. New York: Vintage International.

Perelman, C. & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The new rhetoric: A treatise on argumentation. Translated by John Wilkinson and Purcell Weaver. Notre Dame/London: University of Notre Dame Press.

Perelman, C. (1979). The new rhetoric and the humanities: Essays on rhetoric and its application. Dordrecht: Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1979.

Perelman, C. (1982). The realm of rhetoric. Translated by William Kluback. Notre Dame/London: University of Notre Dame Press, 1982.

Takada, T. (1965). Unmei no shimajima Amami to Okinawa [Destiny’s islands: Amami and Okinawa], Reprint ed. Kagoshima, Japan: Amamisha.

Tindale, C. W. (1999). Acts of arguing: A rhetorical model of argument. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Tindale, C. W. (2004). Rhetorical argumentation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tindale C. W. (2013). Rhetorical argumentation and the nature of audience: Toward an understanding of audience – Issues in argumentation. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 46.4, 508-532.

Warnick, B. & Kline, S. L. (1992). The new rhetoric’s argument schemes: A rhetorical view of practical reasoning. Argumentation and Advocacy 29, 1-15.