ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Argument Theory And The Rhetorical Practices Of The North American ‘Central America Movement’

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

They loved us when we stood in front of the Galleria and sang “El Salvador’s another Viet Nam” to the tune of “Walking in a Winter Wonderland.” But the situation in El Salvador was different from Viet Nam, and we knew that the equation was an oversimplification. But we also knew that we needed something that would get the public’s attention, something that would help them connect with an issue on which we wanted to change American policy.

“We” here is the group of people who made up the Central America Movement, and most, specifically, the Pledge of Resistance, in Louisville, Kentucky. The goal of that group, and of the movement in general, was to end U.S. government support for repressive right-wing governments in Central America and to end the support of the Reagan administration for the Contras who sought to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. The Movement sought to influence policy entirely through democratic means, entirely by using the resources always open to citizens in a democracy: the formation of public opinion and the persuasion of senators and representatives who would be voting on aid bills. Cutting off funding for Reagan administration initiatives was the best procedural way to disable the administration’s policy. The only “illegalities” in which the Movement as I know it engaged were acts of very public – the more public the better – civil disobedience. Throughout the 1980s, the issue of Central America policy never became a “determining” one; that is, it was never an issue on which the majority of Americans based their votes and thus one on which the administration was loath to be at odds with a segment of the electorate. The task of the Central America Movement in North America, therefore, was to try to bring the issue before the public, to persuade the public to oppose administration policy, and to persuade legislators to vote against funding requests.

The success of the Central America movement is difficult to judge. Across the nation, individual senators and representatives came to oppose Contra Aid, and finally the flow of aid was stopped. The Iran-Contra scandal was an embarrassment to the Reagan administration but, to the general disappointment of the Central America Movement, did not precipitate a national revaluation of U.S. Central America policy. Church groups in the North America formed twinning relationships with congregations in Central America, and speaking tours brought activists from the region to audiences all across North America, increasing awareness of the region and familiarity with its issues as seen from a perspective different from that of the administration. It is generally accepted that regimes in Central America are more democratic than was the case in the 1980s. Reconciliation commissions in El Salvador and Guatamala have worked to move those countries beyond armed left/right conflict. Elections in winter of 1990 removed the Sandinista Party from power in Nicaragua and replaced it with a coalition government preferred by the U.S. government. In short, from the perspective of the Central America Movement generally, the news is mixed. It can point to many successes but cannot claim overall to have made Central America policy a key interest of American voters nor to have created popular and legislative support for American policies that would favor the poor or more widely distribute education and health care opportunities among the population in Central America. Contra aid has ended, but a principle of self-determination for the nations of that region has not been enshrined in American foreign policy or American popular opinion.

In looking back at the Central America Movement of the 1980s and attempting an assessment of its rhetoric, we must acknowledge that public and legislative sentiment were strongly influenced by historical events such as the breaking of the Iran-contra scandal and the revelation of atrocities like the mass murders of civilians, the murder of four American churchwomen, and the killing of the Jesuits at the University of Central America in 1990; also by the nationalization of the San Antonio sugar plantation by the Sandinista government and the protest against that government’s economic policy by the women of the Eastern Market in Managua. Events like these never entirely “spoke for themselves,” however. As soon as they were reported, everyone with a stake in the Central America debate rushed to offer interpretations. The “rhetorical sphere” of the Central America Movement was therefore quite large. Well-known writers and intellectuals wrote about the region: Joan Didion’s Salvador and Salman Rushdie’s The Jaguar Smile: A Nicaraguan Journey were particularly successful in bringing some attention to the issue. But such “professional” analyses as these were always quite separate from the activities of the Movement, and it is only the latter that I will be discussing in this paper.

I was a participant in that Movement from 1986 through the early 1990s, and I am proud of that association. My project in this paper is to analyze the argumentation of the Movement and to reflect, in the context of argument theory, on the rhetorical difficulties such movements confront. I am NOT assuming that everyone in the audience shares my political perspective on Central America; I am assuming that the issues raised here are not specific to this particular political movement but rather that they are likely to arise at any intersection of argumentation theory and political commitment.

I am aware that in the U.S. there are two nearly separate scholarly conversations going on at this time about argument: one in English and one in Communication. They are separate not only because of the accidents of university history but also because one takes place within the framework of the Humanities and one within the Social Sciences. The conversation about argument within the field of English is characterized by a focus on texts, the interpretation of texts, the construction of speakers and readers within texts. The Social Sciences conversation, I glean, is more willing to look empirically at the social effects of arguments. The latter is also, I see, more willing to consider the possibility that argument may not avail much in a particular situation (Willard 1989: 4). Within English and Humanities, however, discussions of argument always proceed without much skepticism. This faith in the power of argument may be attributed, I suspect, to the fact that English departments are charged with teaching Freshman Composition to all new University students, and the course includes instruction in the making of and evaluating of arguments. Perhaps we are simply unwilling to entertain the possibility that something that takes so much of our professional energy and provides so much of our institutional raison d’etre may be powerless in certain situations. Let me say at the outset of this paper that I work within the conversation of English and have drawn on its assumptions, its bibliography, and its methods in writing this paper, but the topic has also led me into the Communications, Social Science literature to a limited degree, seeking to understand the social consequences of certain rhetorical choices.

2. Framing the debate

The rhetorical task of the Central America Movement was greatly complicated by the fact that the American electorate as a whole never made Central America policy a voting issue. American troops were not being conscripted to fight there, though National Guard units were being sent in as advisers for short periods of time. In Nancy Fraser’s terms, the movement never achieved the status of a “subaltern counterpublic,” perhaps because participants were not seeking to change the way they themselves were viewed or treated (Fraser 1992: 107). American public life seems to accord some measure of respect to subaltern groups that speak from the subject position of “victim” and demand change. Voices from such subject positions often succeed in creating a public issue. The right of the Movement to speak for the poor in Central America was never obvious or unchallenged, and therein lay one more difficulty in bringing the issue to the fore.

The need to rouse public sentiment pushed the Movement to argument by historical analogy: our national sense of what we must do derives in large part from our interpretation of the present moment as being like some other in our past. We will apply the lessons of history. In the 1990s, the U.S. government’s decisions about the level of engagement in Bosnia were defended with the argument that Bosnia would become another Viet Nam, an unwinnable bloodletting in which we should not get involved; opponents of that policy argued that Bosnia was instead like Europe in the late 1930s, when appeasement and non-involvement proved disastrous. So, the first rhetorical struggle of the Central America Movement in the 1980s was to frame the public understanding of events in that region as analogous to Viet Nam, in opposition to the Reagan administration’s efforts to evoke World War II and even the American Revolutionary War (Reagan famously referred to the Nicaraguan Contras as “the moral equivalent of our founding fathers”).

Analogy with Viet Nam was effective in getting public attention: one could hardly ask for a more painful national experience to reference. Those who opposed that war thought it a moral and personal disaster; those who supported it thought it a military disaster, fraught with political betrayal. No one wanted to relive it. For sheer aversiveness, one could not ask for a stronger analogy. And the Movement felt pushed to employ it to counter the administration analogies with glorious moments in the past. But the Movement never entirely embraced the Viet Nam analogy. There was considerable debate about its use within the Movement, and it was employed sporadically, not systematically. Resistance to its use sprang from the conviction that it was simply a false analogy. El Salvador was not another Viet Nam. If the temptation of generals is always to be fighting the last war, the need to frame a political debate by historical analogy tempts rhetoricians to do the same, to find an historical analogy that will serve politically, even if the fit is not good.

As the 1980s wore on, it became increasingly clear that the Viet Nam analogy was not apt: U.S. policy in El Salvador would never cause upheaval in the lives of North Americans. Further, the Movement became increasingly convinced that the situation in Central America generally was better described as Low Intensity Warfare. Michael T. Klare and Peter Kornbluh’s book by that title, published in 1989, argued that the Reagan administration had learned the lessons of Viet Nam very well indeed and had deliberately developed near -invisible strategies for undermining the Sandinista government in Nicaragua: economic sabotage, paramilitary action, psychological warfare (Klare and Kornbluh 1989: 8).

Convincing the American public that low-intensity warfare was real and was being waged by the Reagan administration against Nicaragua became a goal of at least some segments of the Movement, running counter to the logic of the Viet Nam analogy. But, as the goal became educating the American people about low-intensity warfare, convincing them that something new was being waged in Central America, there was no historical analogy available to draw on in framing the debate. Reference to Viet Nam gained attention, but many believed that it falsified the message of the Movement; low-intensity warfare, however, was largely unknown, pushed no emotional buttons, and garnered little attention.

3. Strategy and ethos

Gaining the attention of the American people was a constant serious problem for the Movement. Unlike other social movements of the last two centuries, it lacked any visible victims and kept slipping into invisibility. It was not so much “Which side are you on?” as “What IS going on?” Leafleting was one way to get the word out. Local groups did generally rely heavily on leafleting, but they discovered that late twentieth-century America has reorganized its social geography in such a way as to make leafleting much more difficult than it was even thirty years ago. The shopping mall has replaced the downtown shopping district; malls are privately owned. Once, groups could leaflet in front of major stores and in the town square. Now, one must have the permission of the corporate owners of malls to do the same; it is generally not forthcoming. Once, groups could leaflet people entering stores and public buildings. Now, people leave public space in their cars, driving unto private property. One cannot give a leaflet to a moving car, and putting leaflets on parked cars in private lots is a clandestine operation.

Should the Movement engage in such clandestine operations? Doing so generally seemed a necessity. How else to break through the silence? How else to bring the issue into the public’s field of vision? How else to say “People’s lives are being ruined; a great injustice is taking place; something must be done to stop it!” If one is morally impelled to speak, then one is morally impelled to speak to be heard. Civil disobedience was a common strategy of the Movement, particularly of a group called the Pledge of Resistance, whose members signed a pledge to engage in non-violent civil disobedience, even to the point of being arrested, if the United States invaded Nicaragua. Movement groups staged sit-ins in Congressional offices and in public venues, and some participants were arrested and tried, protesting aid going to the Contras. This tactic is informally credited with having raised the profile of the issue and persuaded some Congressional representatives to oppose Contra aid.

But what of the truly clandestine? What of tactics designed to force the public to confront the issue: guerrilla theatre, for example? A black van pulls up among the lunchtime crowd in the business district; masked men grab movement participants who have been planted in the crowd and hustle them into the van; then more movement participants walk through the crowd handing out a leaflet that begins, “This is an everyday occurrence in San Salvador.” What of bannering, of suspending a banner from a highway overpass, denouncing the Death-Squad Government of El Salvador or demanding an end to Contra aid? What of three blood-stained mannequins left by the sides of highways with a sign saying that Death Squads that day dumped the bodies of three Salvadoran citizens by the highway leading from the capital, and giving the names of the dead?

Such tactics certainly succeeded in breaking through the barrier of invisibility, at least for those American citizens who witnessed them first-hand. The willingness of newspaper, TV, and radio to cover such events varied from city to city. Generally, the larger cities gave more coverage, while smaller-city media were more likely to ignore them. What effect did such clandestine “arguments” have on the perceived ethos of the movement, in the eyes of the public in general? The answer to that, based on reports of participants themselves, seems also to vary with the size of the city and the local political culture. When in 1992, for example, thousands of San Franciscans shut down the Golden Gate Bridge to protest the Gulf War, the action seems not to have generated noticeable resentment on the part of the citizenry as a whole. In Cincinnati, a heartland city of about half a million people, a similar action by the Teachers’ Union, dramatizing the urgent need for a school-funding levy, backfired badly and sparked an outpouring of hostility toward the union and toward the levy. So it was with the Central America actions: San Francisans and Chicagoans seem generally to have accepted the actions as legitimate political expressions. In Louisville, Kentucky, a heartland city in the upper south, highway bannering sparked a torrent of abuse and ridicule from morning radio disk jockeys. It would seem impossible, therefore, to judge whether such tactics, such argument moves, are or are not effective in absolute terms. Their meaning seems to vary with the speech-act context, as they are read differently in different local political cultures. This lesson would seem of interest not only to argument theorists who want to see argument always within the frame of the speech-act but also to political groups which fund a national office to coordinate activities, often calling for a national “day of action”; they would be well advised to remember that the persuasive power of an action can vary greatly from city to city.

Looking more closely at the difference in interpretation, we can note that the ethos of the movement seems to have been constructed differently in different locations. Larger cities, especially coastal ones, seem to have regarded clandestine actions as an expected part of the political vocabulary. But in smaller, heartland cities, clandestine action seems to have constructed the Movement as an “Other,” an oppositional group with whom many citizens were reluctant to identify. Any anonymous disruption of the norm, carried out under cover of darkness, marked the group as set apart from the mass of the citizenry, if only by its clandestine planning: Movement people were in on the planning; the secret was kept from others. This construct set the Movement apart, created an Us and a Them, and created an ethical gulf that was difficult to breach. At local demonstrations of our group, I cannot remember ever seeing anyone in attendance who was not known to at least one member of the group. It seems a measure of our separateness from the community that we never attracted strangers.

Ironically, such clandestine actions as street theatre and bannering were often the ones that most energized the group itself. Oppositional ACTION seemed to have an inherent appeal, and the ethical self-representation as outlaw had a positive appeal. In addition, there was for many a felt sense of moral imperative to separate oneself in a public way from Reagan administration policy, “to withdraw consent,” as it was often termed. Holly Near, the folk-singer and activist, summed up the motivation of many Movement participants when she wrote the line, “No more genocide in my name.” (“No More Genocide”: Journeys, Redwood Records, 1984). Thus the impetus to separate oneself from the mass of the American citizenry among whom Ronald Reagan was dauntingly popular further served the ethical construction of the Movement as Other.

One element of postmodern argument theory tells us that ethos is the critical element in argumentation, as belief in rational argument erodes (Willard 1989: 4-10). In the absence of societal consensus in which to ground claims and reasons, the ethical standing of the speaker becomes the determining factor in the outcome of argumentation. Ethical self-representation becomes a matter of great political importance. Along with the issues already discussed in that regard, we should again consider the role of historical analogy in the construction of political ethos.

Twentieth-century American political and social history are haunted by the specters of foreign subversives and witch-hunts. Fear of Communist subversion in particular has created a public distrust of clandestine political groups and some suspicion of any organized political interest group (Dietrich 1996: 170-190). One’s credibility as a citizen speaking on any issue is complicated if not compromised if one is believed to be speaking the “party line” of an organized group, from the National Organization for Women to the Christian Right. Conversely, political groups revealed to have been targeted for monitoring by governmental agencies often invoke the historical precedent of the McCarthy-era witch-hunts, which are widely perceived as having victimized innocent citizens and violated civil liberties. When it was revealed that an agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation had infiltrated a local group of Central American activists in Philadelphia, that agency justified its action by asserting that it had reason to believe that the group was planning illegal activity – raising the familiar specter of the subversive cell. The Movement group, always noted as having included members of Catholic religious communities, protested that its civil rights were violated and that the FBI was engaging in a witch-hunt. The same argument dynamic was repeated when members of a Movement group, called Sanctuary, in Texas, including members of religious communities, were arrested for helping Central Americans come to and remain in the United States illegally. The government pointed up the illegality of their activity and its secret and conspiratorial nature; the group responded with moral arguments about the necessity to save the refugees and with outrage that the government had infiltrated their group. Once again, the ethical high ground was the object, and historical analogy was a prime strategy for attaining it.

4. Creating dissensus

If the guerrilla tactics of the Movement raised public awareness of the issue, they were still limited in their ability to create a dissensus that could lead to political action. If the Movement succeeded in making the public suspicious of administration Central America policy, it still had to make that public informed and articulate enough to withdraw their consent by urging their congressional representatives to vote against contra aid, by speaking in public fora, by writing letters, raising the subject with friends, etc. So the Movement recognized a need to provide explicit arguments – claims and reasons.

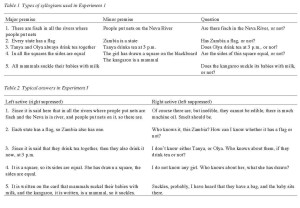

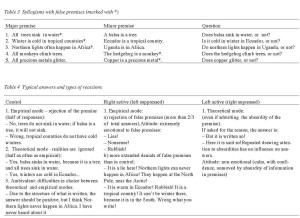

In 1987, leading up to a vote on renewal of Contra aid in the fall Congressional session, the Pledge of Resistance waged a campaign it named “Stop the Lies.” The newsprint paper it sent to members of the Pledge also included a tear-sheet for new signers of the Pledge to fill out and return; thus the intended audience seems to have been Movement members and non-members. It featured a text box on the front page, with the following content: “They lied about trading arms for hostages. They lied about diverting the money to the Contras. In fact, almost everything they’ve told us about Central America is a lie. Some of the lies are simple and bald-faced. Like the repeated denial of illegal U.S. funding of the Contras. And some of the lies are big and complex. Like the lie that the U.S. is promoting democracy in Central America. Or that our government is seeking a negotiated peace. These lies fuel the escalating war in Central America – just as they did during Vietnam. To stop the war, we must first stop the lies.” The paper then lists seven lies and arguments in support of the thesis that they are indeed lies:

#1 The War in Central America is Not Another Vietnam;

#2 The U.S. has Sought a Peaceful Solution in Central America;

#3 U.S. Economic Aid helps the Poor in Central America;

#4 U.S. Policy in Central America is a Response to a Soviet Threat;

#5 U.S. Actions in Central America are Legal;

#6 U.S. Policy is Improving Human Rights in Central America;

#7 U.S. Actions in Central America Promote Democracy.

The analogy with Viet Nam is, of course, prominently asserted here, and supported with data about the number of military advisors sent to the region and with quotations from administration officials that do not foreclose the possibility of invasion. No reason is given for not wanting to repeat the experience of Viet Nam – none need be. Implicit are the moral and pragmatic concerns that always attend a discussion of that conflict. Reasons given in support of the other six assertions explicitly mix the moral and the pragmatic and construct a reader who believes the following:

– peace in Central America is desirable;

– conditions for the poor must be improved;

– respect for human rights must be strengthened;

– democracy in the region must be restored;

– power should move from military and oligarchic elites to the people;

– the United States should respect decisions of the World Court even when they contravene its perceived self-interest; the U.S. has no moral or strategic interest in opposing leftist movements in Central America or no right or responsibility to intervene.

This profile described the beliefs of a minority during the 1980s. The “Stop the Lies” paper supported its assertions about each of the lies with data (such as numbers of civilians killed in Central America since 1979) and with quotations from government sources (“David MacMichael, former CIA analyst responsible for proving that Nicaragua was arming the Salvadoran rebels: ‘There has not been a verified report of arms moving from Nicaragua to El Salvador since April, 1981’.”) Data and quotations are footnoted to credible sources like Time magazine, The New York Times, Americas Watch, and the Wall Street Journal, though one does note the absence of engagement with any opposing claims or evidence.

In sum, the “Stop the Lies” publication reinforces a binary choice between a “they” who have lied to “us” and the victimized “us” who have been so deceived. The subject position of duped victim is not one that people rush to occupy. It offers evidence that leftist movements in Central America are not an extension of Soviet threat to America, but it does not engage the deeper American skepticism about leftist movements in general.

5. The epistemology of oppositional movements

Any discussion of argument and the Central America Movement should engage the question of why that movement was taken off guard by historical events that did not support its interpretation of the dynamic in that region, events such as the La Penca bombing and, most importantly, the electoral defeat of the Sandinista government in the winter of 1990. It may take comfort in the fact that the New York Times was similarly surprised by this latter event, having assessed the chances of the UNO coalition at slim to none. But Central America Movement groups derived much of their rationale and their ethical stature from the belief that they had a “true picture” of the situation in Central America, that they had sources of information in religious and health workers, church and union groups, and individual friends who could provide accurate information that the New York Times would not print because of its politics, that the Reagan administration would actively suppress. Groups like Witness for Peace existed to arrange for North Americans to travel to Central America and see first-hand what things were like, to talk to a cross-section of citizens. It would probably be fair to say that part of what constituted a Movement group as a group was its belief in its epistemological advantage. Skeptical of mainstream reporting, Movement participants relied on the group for information and interpretation.

If what bound a Movement group together as a group was a set of political commitments and shared oppositional interpretation of events, then any questioning of those commitments or interpretations might be destructive of the group as group (Ice 1987). Such a dynamic renders certain things unspeakable; the group cannot entertain some possibilities without courting its destruction as a group. I have no reason to think that anyone voiced doubt about a Sandinista electoral victory and was silenced; I simply pose the question of whether the possibility of a Sandinista loss was rendered unthinkable by the Movement because considering the possibility opened up to reconsideration so many assumptions that had brought participants together into a movement.

In the 1980’s – coeval with the Central America Movement – the rhetorician Peter Elbow was urging professors of Composition and Rhetoric to teach their students the “believing game” and the “doubting game” (Elbow 1986). In the former, a reader reads a text and tries to think of all the ways in which its assertions can be true – one tries to believe. But that exercise, according to Elbow, should be followed by the “doubting game,” in which the reader reads the very same text and tries to think of all possible objections that can be made to its assertions. It would seem to have been a healthy exercise for Movement groups to have formally structured into their group process a version of the “doubting game,” creating a “free space” in which to speculate aloud about the possibility that their information or interpretation might be wrong. Professors of Composition and Rhetoric were not absent from the Central America Movement. In fact, the professional association Conference on College Composition and Communication had a Central America Caucus that met at its annual convention and might communicate between meetings. Why did the pedagogical technique so widely known among this group never enter Movement practice? Put another way, why did our professional knowledge not affect our political practice? Why was our way of arguing unaffected by what we taught about argumentation? I think that the answer to that question is probably complex, including a reluctance of professors to claim an expertise that would give them additional authority in the Movement groups and, perhaps, also the traditional barrier within the discipline of English that prevents our considering the social effects of argumentation as part of our professional horizon. It is this barrier that Ellen Cushman in her article “The Rhetorician as Agent of Social Change” urges us to break down: she writes, “I am asking for a deeper consideration of the civic purpose of our positions in the academy, of what we do with our knowledge, for whom and by what means. I am asking for a shift in our critical focus away from our own navels… ” (Cushman 1996: 12).

6. Conclusion

The Central America Movement in the 1980s provided a means for many North Americans to express and act on their moral and political commitments to a just peace in the region. It provided a counterweight to Reagan administration pronunciations and made Central America policy an issue in the United States. It mobilized public protest against Contra aid and mobilized thousands of people who pledged to engage in non-violent civil disobedience if the U.S. invaded Nicaragua. It did not succeed in becoming a mass movement or in stopping Contra aid until the end of the decade. In its attempt to persuade the American public, the Movement was caught between the need to gain attention with brief, emotionally charged slogans and the desire to convince the American people of complex processes (illegal arms transactions; low-intensity warfare). Ingrained in American political argumentation is the use of historical analogy to promote an interpretation of present events and a future course of action. Such analogies may be necessary, but they do not well serve explication of new historical situations and processes, and they can constrain the thinking of political groups so that they are “always fighting the previous war,” using tactics that worked in a previous historical situation but are no longer as effective. Tactics like guerrilla theatre succeeded in gaining public attention but varied in their effectiveness from one locale to another. The ethical self-representation of Movement groups was always problematic because participants were not protesting their own oppression; unable to occupy the subject position of “victim,” participants lacked a readily definable warrant for their actions.

The long shadow of history provides interpretive frameworks for political groups, their actions, and their treatment by the government; the Central America Movement was thus associated with Communist subversive groups, and it protested government infiltration as a witch-hunt. When the Movement provided claims and reasons, it appealed to morality and to pragmatism and constructed a reader who was committed to fairness, legality, and the good of the whole population in Central America, but it did not engage the American public’s inherent distrust of any faction termed “leftist.” Unlike the anti-war movement of the 1960s, the Central America Movement was largely unable to break through that barrier because there existed no counter-balancing threat to the American public, such as conscription and American combat deaths had been.

Finally, a sense of epistemological privilege which was common among Movement groups made it difficult for them to foresee events which their interpretations of events did not predict (e.g., the Sandinista electoral loss). The maintenance of solidarity within groups worked against skepticism about information that came through movement channels. Although pedagogical techniques for encouraging healthy dissensus were widely known among professors of Rhetoric and Composition at the time, these did not make their way into Movement practice.

REFERENCES

Cushman, E. (1996). The Rhetorician as an Agent of Social Change. College Composition and Communication 47, 7-28.

Didion, J. (1983). Salvador. New York: Washington Square Press.

Dietrich, J. (1996). The Old Left. New York: Twayne.

Elbow, P. (1986), Embracing Contraries: Explorations in Teaching and Learning. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fraser, N. (1992) Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy. In: C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the Public Sphere (pp. 107-142), Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ice, R. (1987). Presumption as Problematic in Group Decision-Making: The Case of the Space Shuttle. In: J.W. Wenzel (ed.), Argument and Critical Practices. Speech Communication Association.

Klare, M.T. & P. Kornbluh (1988) Low Intensity Warfare. New York: Random House.

Near, H. (1984) No More Genocide in My Name. Recorded on Journeys. Redwood Records.

Rushdie, S. (1987). The Jaguar Smile: A Nicaraguan Journey. New York: Penguin.

Rushdie, S. (1987) Stop the Lies. Washington, D.C.: The Pledge of Resistance.

Willard, C.A. (1989). A Theory of Argumentation. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.