ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Delivering The Goods In Critical Discussion

1.The pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation [i]

1.The pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation [i]

In the 1970s, inspired by Karl Poppers critical rationalism, an approach to argumentation was developed at the University of Amsterdam that aimed for a sound combination of linguistic insight from the study of language use often called pragmatics and logical insight from the study of critical dialogue known as philosophical dialectics (van Eemeren and Grootendorst 1984). Therefore, its founders labelled this approach pragma-dialectics. In pragma-dialectics, argumentation is viewed as a phenomenon of verbal communication; it is studied as a mode of discourse characterized by the use of language for resolving a difference of opinion. Its quality and possible flaws are measured against criteria connected with this purpose.

In the 1980s, a comprehensive research programme was developed. This programme was, on the one hand, based on the assumption that a philosophical ideal of critical rationality must be developed, in which a theoretical model for argumentative discourse in critical discussion could be grounded. On the other hand, the programmes point of departure was that argumentative reality has to be investigated empirically to achieve an accurate description of actual discourse processes and the various factors influencing their outcome. In the analysis of argumentative discourse the normative and descriptive dimensions were to be linked together by a methodical reconstruction of the actual discourse from the perspective of the projected ideal of critical discussion. Only then, the practical problems of argumentative discourse as revealed in the reconstruction could be diagnosed and adequately tackled.[ii]

Crucial to grounding the pragma-dialectical theory in the philosophical ideal of critical rationality is a model of critical discussion. The model provides a procedure for establishing methodically whether or not a standpoint is defensible against doubt or criticism. It is, in fact, an analytic description of what argumentative discourse would be like if it were solely and optimally aimed at resolving a difference of opinion. The model specifies the various stages and rules of the resolution process, and the types of speech act instrumental in each particular stage.

2.Current research projects in pragma-dialectics

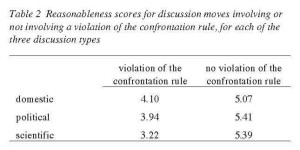

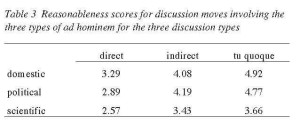

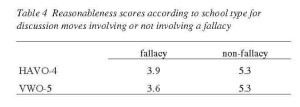

Because the rules for critical discussion are a specification of the norms discussants need to observe in order to resolve a difference, it is to be expected that people who resolve their differences by means of argumentative discourse will maintain norms that are, at least in part, equivalent with the pragma-dialectical rules. To determine systematically to what extent the pragma-dialectical rules agree with the norms applied – or favoured – by ordinary language users, the pragma-dialecticians have embarked upon a research project aimed at testing the ‘conventional’ validity of these rules.[iii] In this project, as reported in this volume, experimental empirical investigations are carried out in which ordinary language users assess fragments of argumentative discourse that contain various kinds of fallacious discussion moves for their acceptability.[iv] The results provide general insight into ordinary language users’ conceptions of reasonableness.

Another research project that has been started with the ideal of critical discussion as its point of departure, deals with the verbal means used in argumentative discourse to indicate the communicative and interactional functions of the various verbal moves. The aim of this project is to make an inventory of potential indicators of moves that are relevant for a critical discussion – and to identify the conditions for giving a certain expression a specific function in the resolution process. In her contribution to this volume, Francisca Snoeck Henkemans explains that the scope of the project is not restricted to well-known relational indicators such as ‘therefore’, and indicators of argumentation such as ‘my reasons for this are’, but extends to indicators of counterarguments and relations between arguments, and also to indicators of moves in other stages of the resolution process: expressing antagonism, granting concessions, adding a rebuttal, et cetera.[v]

In Reconstructing Argumentative Discourse, co-authored by Frans van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, Sally Jackson and Scott Jacobs, the ideal of critical discussion is used as a point of departure for the analysis of a variety of specimens of argumentative discourse. Such an analysis results in an analytic overview that can be the basis for a critical evaluation. It makes clear what the difference of opinion is that is developed in the confrontation stage, which positions are being taken and which premisses serve as the starting point in the opening stage, which arguments and criticisms are – explicitly or implicitly – advanced and which argumentation structures and argument schemes are being used in the argumentation stage, and what conclusion is finally reached in the concluding stage. Because the speech acts – and combinations of speech acts – that play a part in the various stages of the resolution process are all specified in the model of critical discussion, the model is a heuristic tool for reconstructing implicit or otherwise opaque speech acts (van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Jackson, and Jacobs 1993). Until recently, pragma-dialectical analysis tended to concentrate on reconstructing primarily the dialectical aspects of argumentative discourse. It is clear, however, that the analysis and its justification can be considerably strengthened by a better understanding of the strategic rationale behind the moves that are made in the discourse. For this purpose, it is indispensable to incorporate a rhetorical dimension into the reconstruction of the discourse. The project we report about in this paper aims at integrating rhetorical insight methodically into the pragma-dialectical method of analysis.

3. Strategic manoeuvring in resolving a difference

Characteristically, people engaged in argumentative discourse share an orientation towards resolving some difference of opinion. They may be regarded as committed to the norms instrumental in achieving this purpose – maintaining certain standards of reasonableness and expecting others to comply with the same critical standards. This is, of course, not to say that they do not want to resolve the difference of opinion in their own favour. In practice, their argumentation and other speech acts may even be assumed to be designed to achieve precisely this effect.[vi] There is, in other words, always a rhetorical aspect to argumentative discourse.[vii]

The rhetorical pervasion of argumentative discourse does not mean that the parties involved are interested exclusively in getting things their way.[viii] Even when they try as hard as they can to get their point of view accepted, it is by no means necessarily so that they adopt an unreasonable attitude. They have, at any rate, to maintain the image of people who play the resolution game by the rules: they may be considered committed to what they have said, assumed or implicated. As a rule, they will at least pretend to be primarily interested in having the difference of opinion resolved. If a move is not appropriate, they cannot escape from their dialectical responsibility by simply saying ‘I was only being rhetorical’.[ix]

The balancing of a resolution-minded dialectical objective with the rhetorical objective of having one’s own position accepted is prone to give rise to strategic manoeuvring. Generally, the parties will seek to fulfill their dialectical obligations without sacrificing their rhetorical aims. In the process, they will attempt to make use of the opportunities available in the dialectical situation for steering the conclusion of the discourse rhetorically in the direction that serves their own interests best.[x] In our view, an adequate analysis of argumentative discourse should take account not only of its dialectical dimension but also of its rhetorical dimension. To enrich the pragma-dialectical method of analysis with rhetorical insight, we view rhetorical moves as operating within a dialectical framework. This means that insight into strategic manoeuvring in argumentative discourse as it occurs in practice is incorporated in a resolution-oriented reconstruction.[xi] New conceptual tools must be developed for carrying out and justifying such an integrated analysis.

4. Integrating rhetoric into pragma-dialectical analysis

Since antiquity, there has been a division between rhetoric and dialectic.[xii] According to Toulmin’s (1997) Thomas Jefferson Lecture, this division became ideologized with the Peace of Westphalia (1648). It led to the separate existence of two mutually isolated paradigms, which are seen as incompatible and as conforming to entirely different conceptions of argumentation[xiii] – if not a total neglect of this subject.[xiv]

Within the humanities, rhetoric has become the field of scholars in communication, language and literature. After already having been incorporated into logic by Ramus, dialectic has – with the further formalization of logic – in fact almost disappeared from sight. Although recently the dialectical approach to argumentation has been taken up again, there still appears to be among argumentation theorists a yawning gap between those formally-oriented theorists who opt for a dialectical approach and the humanist protagonists of a rhetorical approach.[xv]

On closer inspection – we have elaborated on this elsewhere (van Eemeren and Houtlosser 1997) – there have always been authors who see a connection between rhetoric and dialectic. For Aristotle, rhetoric is the mirror image or counterpart (antistrophos) of dialectic.[xvi] In the Rhetoric, he assimilated the opposing views of Plato and the sophists (Murphy and Katula 1994: Ch. 2). According to Reboul, in the first chapter Aristotle wrote ‘que la rhétorique est le “rejeton” de la dialectique, c’est à dire son application, un peu comme la médicine est une application de la biologie. Mais ensuite, il la qualifie comme une “partie” de la dialectique’ (1991: 46). In late antiquity, Boethius subsumes rhetoric in De topicis differentiis under dialectic (Kennedy 1994: 283). According to Mack, ‘for Boethius dialectic is more important, providing rhetoric with its basis’ (1993: 8, n. 19). Mack explains that the development of humanism ‘provoked a reconsideration of the object of dialectic and a reform of the relationship between rhetoric and dialectic’ (1993: 15).

In De inventione dialectica libri tres (1479/1991), a major contribution to humanist argumentation theory, Agricola builds on Cicero’s view that dialectic and rhetoric cannot be separated and merges the two into one theory.[xvii] Unlike Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, who bring elements from dialectic into rhetoric, Agricola incorporates elements from rhetoric into dialectic.[xviii] We opt for a similar approach.

To overcome the sharp and infertile ideological division between rhetoric and dialectic, we view dialectic as a theory of argumentation in natural discourse, fitting rhetorical insight into persuasion techniques into this theoretical framework.[xix] In the words of van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Jackson and Jacobs, dialectic is ‘a method of regimented opposition [in verbal communication and interaction] that amounts to the pragmatic application of logic, a collaborative method of putting logic into use so as to move from conjecture and opinion to more secure belief’ (1997: 214).[xx]

The Aristotelian rhetorical norm of successful persuasion is not necessarily in contradiction with the ideal of reasonableness that lies at the heart of this pragma-dialectical approach. Why would it be impossible to comply with critical standards for argumentative discourse when attempting to shape one’s case to one’s own advantage?[xxi] A critical audience will probably require rhetorically strong argumentation to be in agreement with the dialectical norms pertaining to the discussion stage concerned.[xxii] From this point of departure, we have started to integrate the rhetorical dimension into the pragma-dialectical method for analysis.[xxiii]

5. Levels of manoeuvring in different stages

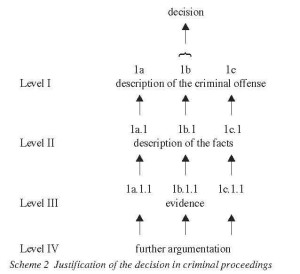

An understanding of the role of strategic manoeuvring in resolving a difference of opinion will deepen and strengthen the pragma-dialectical reconstruction of argumentative discourse. It does so by revealing how the opportunities available in a certain dialectical situation are used to complete a particular discussion stage most favourably for the speaker or writer. Each stage in the resolution process constitutes a dialectical situation that is characterized by a specific aim. As the parties involved want to achieve the definition of the dialectical situation most beneficial to their own purposes, they will attempt to make the strategic moves that serve this interest best. Therefore, the dialectical aim prevailing in a particular discussion stage always has a rhetorical analogon as its corollary. Because what kind of advantages can be gained depends on the dialectical stages, the presumed rhetorical aims of the participants must be specified according to stage.

Rhetorical manoeuvring can consist in making a choice from the options constituting the topical potential associated with a particular discussion stage, in deciding on a certain adaptation to auditorial demand, and in taking a policy in the exploitation of presentational devices. Given a certain difference of opinion, speakers or writers can choose the material they find easiest to handle; they can choose the perspective that is most agreeable to the audience; and they can sketch this perspective in their verbal presentation in the most flattering colours. On each of these three levels of manoeuvring, they have a chance to influence the result of the discourse strategically.

The topical potential associated with a particular dialectical stage can, in our view, be regarded as the collective of relevant alternatives available in that stage of the resolution process.[xxiv] As Simons (1990) observes, the ancient Greeks and Romans were already aware that on any issue there is a finite range of stratagems that can be called upon when discussing a case. Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca rightly emphasize that from the very fact that certain elements are selected, ‘their importance and pertinence to the discussion are implied’ (1969: 119). Apart from endowing elements with a ‘presence’ deliberate suppression of presence is, in their view, also a noteworthy phenomenon of choice (1969: 116).[xxv] Other modes of choice are defining a difference of opinion, or interpreting a starting point, in the way the speaker or writer finds easiest to cope with.

On the level of making a choice from the topical potential, strategic manoeuvring in the confrontation stage aims, for example, at making the most effective choice among the potential issues for discussion – restricting the ‘disagreement space’ in such a way that the confrontation is defined in accordance with the speaker or writer’s preferences. In the opening stage, strategic manoeuvring attempts to create the most advantageous starting point for the speaker or writer, for instance by calling to mind – or eliciting – helpful ‘concessions’ from the other party. In the argumentation stage, starting from the list of ‘status topes’ associated with the type of standpoint at issue, a strategic line of defence involves the selection from the available loci that best suits the speaker or writer. In the concluding stage, all efforts will be directed towards achieving the conclusion of the discourse desired by the speaker or writer, for instance by pointing out the consequences of accepting a certain complex of arguments.

In order to achieve the optimal rhetorical result, the moves that are made must in each stage of the discourse be adapted to auditorial demand in such a way that they comply with the audience or readership’s good sense and preferences.[xxvi] Argumentative moves that are entirely appropriate to some may be inappropriate to others. In general, adaptation to auditorial demand will consist in an attempt to create ‘communion’. This may manifest itself in the confrontation stage, for example, by the avoidance of unnecessary or unsolvable contradictions. According to Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, disagreement with respect to values is sometimes communicated to the audience as disagreement over facts, because it is easier to accommodate. As a rule, a speaker’s or writer’s effort is directed to ‘assigning […] the status enjoying the widest agreement to the elements on which he is basing his argument’ (1969: 179). This explains why, in the opening stage, the status of a widely shared value judgement may be conferred on personal feelings and impressions, and the status of fact on subjective values. In the argumentation stage, strategic adaptation to auditorial demand may be achieved by quoting arguments the listeners or readers agree with or referring to argumentative principles they adhere to. In order to achieve the optimal rhetorical result, all available presentational devices must be strategically exploited in the discourse. This means that the moves should be systematically chosen for their discursive and stylistic effectiveness. In De oratore, Cicero observed an unbreakable unity between expression and content – verbum and res. Anscombre identifies expression with orientation: ‘signifier pour un énoncé c’est orienter: non décrire ou informer, mais diriger le discours dans une certaine direction’ (1994: 30). According to Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, all argumentative discourse presupposes ‘a choice consisting not only of the selection of elements to be used, but also of the technique for their presentation’ (1969: 119).

Rhetorical figures that can be used as presentational devices are specific modes of expression; they are ways of presenting which make things present to the mind.[xxvii] Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca regard a figure as argumentative if it brings about a change of perspective (1969: 169).[xxviii] Among the many rhetorical figures that can serve argumentative purposes are – to name just a few classical examples – praeteritio and rhetorical questions. It depends on the stage of the discourse which figure may be helpful. According to Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, figures such as metalepsis can, for instance, facilitate the transposition of values into facts, as in ‘remember our agreement’ for ‘keep our agreement’ (1969: 181).

Only if in a certain stage of the discourse the speaker or writer’s strategic manoeuvrings on the levels of topical potential, auditorial demand, and presentational devices converge, shall we say that a ‘rhetorical strategy’ is being followed. Rhetorical strategies in our sense are methodical designs of moves manifesting themselves in argumentative discourse on all three levels in the systematic, co-ordinated and simultaneous use of the available opportunities for influencing the result of a specific dialectical stage to one’s own advantage. There are confrontation strategies, such as evasion or ‘humptydumptying’ in defining the difference. There are also opening strategies, such as creating a broad zone of agreement or, the opposite, a ‘smokescreen’. Included in such argumentation strategies are spelling out factual consequences and ‘knocking down’ the opponent. A notorious concluding strategy is forcing the audience to ‘bite the bullet’. In our view, the various rhetorical styles used in conducting argumentative discourse are characterized by a particular combination of the use of such strategies.

6. Delivering the goods in William the Silent’s Apologie

This proclamation is at the same time the conclusion of this paper. In a second paper, entitled William the Silent’s argumentative discourse (this volume), we illustrate our method of analysis by providing a partial reconstruction of this 16th Century revolutionary’s Apologie.

NOTES

i. We thank Dale Brashers, Eveline Feteris, Bart Garssen, Susanne Gerritsen, David Hitchcock, Scott Jacobs, Bert Meuffels, Agnès van Rees, Maarten van der Tol and John Woods for their useful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

ii. In the pragma-dialectical research programme, argumentative discourse is approached with four basic metatheoretical, or methodological, starting points: the subject matter under investigation is to be externalized, socialized, functionalized, and dialectified.

iii. Each of the pragma-dialectical discussion rules constitutes a distinct standard for critical discussion. An infringement of any of the rules, whichever party commits it and at whatever stage in the discussion, is a possible threat to the resolution of a difference of opinion and must therefore be regarded as an incorrect discussion move or fallacy. It can be shown that the pragma-dialectical rules are problem valid in the sense that non-compliance with any of the rules is an impediment to the resolution of a difference of opinion. In order to be effective in resolving a difference, they must also be intersubjectively acceptable to people who wish to resolve their differences by means of argumentative discourse: they have to be tested for their conventional validity.

iv. See van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Meuffels, and Verburg (this volume). The results of these empirical investigations also provide an empirical basis for developing textbooks in which appropriate pedagogical attention is paid to specific argumentation rules.

v. Argumentative connectors, such as incidentally, in addition and since because provide information about the structure of the argumentation, even and let alone, about the relative weight of arguments, and nevertheless and still about their oppositional character.

vi. Simons (1990) observes that in this endeavour all issues must be named and framed, all facts interpreted, and the argumentative discourse must be adapted to an end, an audience, and the circumstances.

vii. In a general sense, all discourse is rhetorical since the participants are intent on making a certain impression on their audience, for instance by being polite. See Leech (1983) and Levinson (1983).

viii. Although in some cases rhetorical goals appear to be pursued that are entirely foreign to resolving a difference – e.g. being perceived as nice – argumentative discourse – purportedly – always aims at resolving a difference.

ix. According to the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation, rhetorical moves that violate a dialectical norm are contra-dialectic, and are to be considered fallacious. See for this approach to fallacies van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1992).

x. In this, we disagree with Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, who differentiate between rhetorical debate and dialectical discussion: ‘discussion came to be considered as a sincere quest for the truth, whereas the protagonists of a debate are chiefly concerned with the triumph of their own viewpoint’ (1969: 38).

xi. In doing so, the differences between the real and the ideal are appropriately appreciated. See van Eemeren and Houtlosser (1997). Reality differs from the ideal in the sense that the ideal model of critical discussion not only includes only elements that are functional in resolving a difference, but also transcends the vices of argumentative practice.

xii. In Aristotle’s view, these disciplines (and analytics) were ‘supplementary’ to disciplines that have their own substance. See Gaonkar (1990).

xiii. According to Govier, rhetoric and dialectic represent different perspectives on argumentation: ‘argue to win our case’ and ‘argue in search of the truth’ (1997: 73).

xiv. The geometrical world view, and the accompanying formal paradigm of the exact sciences, had become synonymous with rationality. For the humanists, argumentation had been part of an attempt to resolve a difference of opinion between people in a reasonable way, with rhetoric playing a legitimate role in the resolution process. In the exact sciences reasonable argumentation was equated with reasoning rationally by means of formal derivations – and rhetoric did not have a part.

xv. On one side there are the dialectical theories of argumentation with a formal – arhetorical – character, such as Hamblin’s (1970) and Barth and Krabbe’s (1982) ‘formal dialectic’ (based on the dialogue logic of the Erlangen School) and the formal approach to the fallacies by Woods and Walton (1989). On the other side are the rhetorical – anti-formal – functional and contextual approaches, such as Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s (1969) ‘new rhetoric’ and the rhetorical tradition in American speech communication and among philosophers.

xvi. Reboul observes that for antistrophos the translators ‘donnent […] tantôt “analogue”, tantôt “contrepartie”’. He adds (1991: 46): ‘Antistrophos: il est gênant qu’un livre commence avec un terme aussi obscur!’

xvii. For Cicero rhetoric is also disputatio in utramque partem, speaking on both sides of an issue.

xviii. According to Mack, Agricola’s work is unlike any previous rhetoric or dialectic: ‘[He] has selected materials from the traditional contents of both subjects’ (1993: 122). In Meerhoff’s (1988: 273) view, ‘pour Agricola, […] loin de réduire la dialectique à la seule recherche de la vérité rationelle, il entend parler de celle-ci en termes de communication.

xix. Kienpointner (1995: 453) points out that many scholars see rhetoric as ‘a rather narrow subject dealing with the techniques of persuasion and/or stylistic devices’, while others conceive of rhetoric as ‘a general theory of argumentation and communication’ (and still others deny that it is a discipline at all). According to Simons (1990), most neutrally, rhetoric is the study and the practice of persuasion.

xx. In thus defining dialectic as discourse dialectic, our conception differs in various ways from Aristotelian, Hegelian and formal dialectic.

xxi. Since the recent revaluation of rhetoric, there is a general acknowledgement that the a-rational – and sometimes even anti-rational – image of rhetoric must be revised. According to Gaonkar (1990), this ‘rhetorical turn’ explicitly recognizes the relevance of rhetoric for criticism and as an interpretative method.

xxii. Some other theoreticians, such as Reboul, also recognize that rhetorically strong argumentation should comply with dialectical criteria: ‘On doit tout faire pour gagner, mais non par n’importe quels moyens: il faut jouer [le jeu] respectant les règles’ (1991: 42). See also Wenzel (1990).

xxiii. For other proposals to subordinate rhetoric to dialectic, see, for example, Natanson (1955). See also Weaver (1953).

xxiv. In the way we use the term topics, there are topical systems for all discussion stages, not just for the argumentation stage.

xxv. Edward Kennedy’s ‘Chappaquidick speech’ illustrates how suppression of presence can be used strategically. See van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Jackson, and Jacobs (1993: vii-xi) and van Eemeren and Houtlosser (1997).

xxvi. In our approach, the audience is not just Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s ‘ensemble of those whom the speaker wishes to influence by his argumentation’ (1969: 19), but coincides with the antagonist in a critical discussion.

xxvii. Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca regard a rhetorical figure as ‘a discernible structure, independent of the content, […] a form (which may […] be syntactic, semantic or pragmatic) and a use that is different from the normal manner of expression, and, consequently, attracts attention’ (1969: 168).

xxviii. In Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s opinion, ‘if the argumentative role of figures is disregarded, their study will soon seem to be a useless [or literary] pastime’ (1969: 167).

REFERENCES

Agricola, R. (1479/1991). Over dialectica en humanisme [On dialectic and humanism]. Edited, with introduction and notes, by Marc van der Poel. Baarn: Ambo.

Anscombre, J.C. (1994). La nature des topoï. In: J.C. Anscombre (Ed.), La théorie des topoï (pp. 49-84). Paris: Editions Kimé.

Barth, E.M. & E.C.W. Krabbe (1982). From Axiom to Dialogue. A Philosophical Study of Logics and Argumentation. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst (1984). Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussions. A Theoretical Model for the Analysis of Discussions Directed towards Solving Conflicts of Opinion. Dordrecht/Berlin: Foris/Mouton de Gruyter.

Eemeren, F.H. van, R. Grootendorst, S. Jackson & S. Jacobs (1993). Reconstructing Argumentative Discourse. London/ Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, R. Grootendorst, S. Jackson & S. Jacobs (1997). Argumentation. In: T.A. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse as Structure and Process. Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, Vol. I (Ch. 8, pp. 208-229). London: Sage.

Eemeren, F.H. van & P. Houtlosser (1997). Rhetorical rationales for dialectical moves. In: J. Klumpp (Ed.), Proceedings of the Tenth NCA/AFA Conference on Argumentation (pp. 51-56). Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association.

Gaonkar, D.P. (1990). Rhetoric and its double: Reflections on the rhetorical turn in the human sciences. In: H.W. Simons (Ed.), The Rhetorical Turn. Invention and Persuasion in the Conduct of Inquiry (pp. 341-366). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Govier, T. (1997). Socrates’ Children. Thinking and Knowing in the Western Tradition. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview.

Hamblin, Ch.L. (1970). Fallacies. London: Methuen.

Kennedy, G.A. (1994). A New History of Classical Rhetoric. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kienpointner, M. (1995). Rhetoric. In: J. Verschueren, J.-O. Östman & J. Blommaert (Eds.), Handbook of Pragmatics. Manual (pp. 453-461). Amsterdam/Philidelphia: John Benjamins.

Kneale, W. & M. Kneale (1962). The Development of Logic. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Leech, G.N. (1983). Principles of Pragmatics. London: Longman.

Levinson, S.C. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mack, P. (1993). Renaissance Argument. Valla and Agricola in the Traditions of Rhetoric and Dialectic. Leiden: Brill.

Meerhoff, C.G. (1988). Agricola et Ramus: dialectique et rhétorique. In: F. Akkerman & A.J. Vanderjagt (Eds.), Rodolphus Agricola Phrisius 1444-1485 (pp. 270-280). Leiden: Brill.

Murphy, J.J. & R.A. Katula (Eds.) (1994). A Synoptic History of Classical Rhetoric. Davis, CA: Hermagoras Press (Originally published 1972).

Natanson, M. (1955). The limits of rhetoric. Quarterly Journal of Speech 41, 133-139.

Perelman, Ch. & L. Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969). The new rhetoric. A treatise on argumentation (Translation of La nouvelle rhétorique. Traité de l’argumentation. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1958). Notre Dame/London: University of Notre Dame Press.

Reboul, O. (1991). Introduction à la rhétorique. Théorie et pratique [Introduction to rhetoric. Theory and practice]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Simons, H.W. (1990). The rhetoric of inquiry as an intellectual movement. In: H.W. Simons (Ed.), The Rhetorical Turn. Invention and Persuasion in the Conduct of Inquiry. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Toulmin, S. (1997). A dissenter’s life. Thomas Jefferson Lecture, March 24, 1997.

Weaver, R. (1953). The Phaedrus and the nature of rhetoric. In: R. Weaver, The Ethics of Rhetoric (pp. 3-26). Chicago: Henry Regnery.

Wenzel, J.W. (1990). Three perspectives on argument: Rhetoric, dialectic, logic. In: R. Trapp & J. Schuetz (Eds.), Perspectives on Argumentation. Essays in the Honor of Wayne Brockriede (pp. 9-26). Prospect Heights, Ill.: Waveland Press.

Woods, J. & D.N. Walton (1989). Fallacies: Selected Papers, 1972–1982. Dordrecht/Berlin: Foris/Mouton de Gruyter.