ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Interactional Resources Of Argumentation

In the following paper I focus on some rhetorical practices that are used by interactants in arguments with others. I identify argument criteria interactants refer to and describe how they use them as interactional resources for their argumentation. My considerations are part of a broader study of conversational rhetoric in problem oriented and conflict interaction, conducted at the Institute for German Language in Mannheim, Germany (see Kallmeyer 1996). The main goal of this project is the analysis and description of interactive practices under a functional rhetorical perspective which is derived from an ethnomethodological approach to the study of conversation. Ethnomethodologists have so far mainly looked at the organizational order of interaction (see Garfinkel & Sacks 1970), we also investigate on forms of interactive influence and interactive effects of the participants’ interactive work.

In order to describe a wide range of rhetorical practices we take into account various dimensions of interaction that have been explicated by Kallmeyer and Schütze in a theory of the construction of interaction (Kallmeyer & Schütze 1976). According to this theory interactants have to carry out their conversation by simultaneously dealing with different dimensions of interactional organization (listed in Figure 1):

Organizational structure of talk

Thematical organization

Activity organization

Identity and relationship construction

Modality construction

Reciprocity organization

Figure 1 Dimensions of interaction construction

Concerning rhetorical practices, there are for example different practices of cooperation and constraint that are required due to the organizational structures of talk, or practices of social positioning of the participants due to identity and relationship construction, or practices of setting and blocking perspectives due to reciprocity demands. The context of my argumentation analysis is the dimension of thematical organization in problem and conflict interaction. Argumentation as a whole is seen then as one rhetorical practice for thematical clarification amongst other patterns such as for example story telling, reports, or portraying (see Kallmeyer & Schütze 1978). Thus, first I had to analyze argumentation as a whole and to work out the conditions under which argumentation is established and carried out in interaction.

Briefly put, interactants begin an argumentation when their thematical exchange runs into a deficit. Then they have to explain and give reasons. Typical deficits include dissent or uncertainty. Argumentation, then, is an interactive pattern for explaining a position and for locally clarifying the deficit and for then integrating the solution of the deficit into the „normal“ course of the current interaction. Formally characterized, argumentation has a three part structure consisting of initiating, carrying out and reintegration. I do not want to specify the difficulties of the empirical analysis of the argumentation pattern but to focus on argumentative relevances that interactants deal with during their argumentation. In the course of that I will point out resources of argumentation which are made relevant from the participants themselves in rhetorical argument practices.

Before presenting these resources and practices I will briefly explain the methodology that we have used. First of all, I defined segments of argumentation in about sixty video- or audiotaped and transcribed conversations from a wide range of problem and conflict interaction situations such as mediation talk, mother-daughter or partner-conflict talk, counselling sessions, TV-discussions, and so on.[i] Within these segments I looked for either explicit complaints or particularly expanded formulations produced by the interactants. These activities were analyzed in a pragma-semantic perspective for criteria that the participants themselves make relevant as argument criteria. They complain about incorrect argumentation moves of their respective partners, or otherwise characterize some of their own activities as particularly important. In this fashion, I use the participants’ perspective in my methodical approach.

In this fashion, I could identify two groups of criteria or resources of argumentation: one group which reflects certain conditions and organizational constraints of conversational argument, and another group where the interactants exchange thematical moves in different modality formats as arguments.

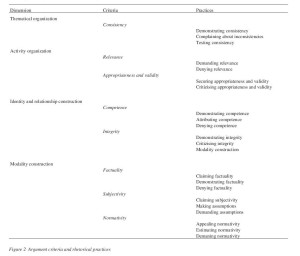

I will now present the criteria in both groups in a synoptical way, and explain them and their relation to the different dimensions of interaction. I will thereby shortly indicate how interactants use these criteria as resources to construct rhetorical practices for their argumentation. After that I will give some examples of some of these practices, their formats, linguistics, and their positive or problematic interactive effects.

The first group, which reflects certain conditions and organizational requirements of conversational argumentation, contains the following five criteria:

1. Interactants demonstrate thematical consistency and consistency of their utterances, they check it, or they complain about inconsistencies of their partners’ argumentation. Consistency refers to contradictions and (in)coherencies and is seen both, locally and globally in the course of argumentation. Dealing with consistency is relevant in the dimension of thematical organization.

2. Interactants demand interactional relevance of the partners’ activity, or they deny it. Relevance is a very strong and often-used argument. Interactants always organize the course of their mutual argumentation by referring to relevance. Relevance as a criterion or an argumentative rhetorical resource belongs to the dimension of activity organization (which includes a wide range of activities from a single speech act to the global activity tasks, such as for example, counselling or mediating).

3. Another criterion operates in the same dimension of activity organization: argumentants make sure that their activities are appropriate and valid in relation to the global activity tasks and to the thematic development oft the argumentation. Otherwise they critizise the inappropriateness and invalidity of the partners’ argument.

4. Argumentants also use qualities of identity as argument criteria. One important criterion then is, whether the partners are competent to deal with the discussed topics or not. In argumentation the partners demonstrate their competence, for example, by deriving it from personal experience, or from professional knowledge; they attribute competence to their partners or they deny their partners’ competence. Discussions of the respective partners’ competence operates in the dimension of identity and relationship construction in interaction.

5. Also in this dimension, a further criterion operates which argumentants take into consideration: argumentative integrity. Interactants demonstrate in argumentation that they are trustworthy and authentic, that they pay attention to the partners’ interactive rights and so on. Or they critizise their partners for ignoring such integrity demands.

The second group of argument criteria is at the heart of argumentation. Interactants exchange thematical activities in different modality formats as arguments. This group of interactive arguments deals with epistemic or deontic modes and therefore operates in the interactive dimension of modality construction.

6. Primarily, argumentants deal with factuality. They claim what they are saying as real or factual. And they sometimes even demonstrate the factuality of their assertions. Otherwise they also deny factuality of their partners’ assertion. And they do so in an epistemic mode of objectivity.

7. In contrast to the presentation of objectivity argumentants also claim a subjective epistemic mode. They characterize what they are saying as subjective, for example, as their personal conviction. They also formulate assumptions and demand their partners’ assumptions.

8. And, finally, argumentants deal in a deontic mode with normativity: while arguing they appeal to social norms, they estimate their own or their partners’ arguments in relation to such norms, or they put in a normative claim regarding their partners’ activities.

The criteria and rhetorical practices that I have mentioned in this synoptical fashion reveal the fundamental characteristics of discursive argumentation. These are not meant as exclusive categories: for example, competence sometimes interferes with integrity or with relevance in such a way that critizising disintegrity also aims at denying competence, or the alleged lack of competence also makes an activity irrelevant – language use is always ambi- or even polyvalent. But in analyzing argumentative discourses you will regularily find these criteria and practices (listed in figure 2) and you can exhaustively analyze with them the argumentative exchange in discourse.

In a discourse analytic perspective you have to bear in mind, however, that argumentants do not really work out what is true or right. None of the above categories has any argumentative ontological state. Argumentants otherwise always do interactively negotiate what is fact, which norm is right, what is relevant for them and so on. Interactively valid is only what argumentants accept by arguing interactively (see Deppermann 1997, Chs. I.2.5 and III.4).

In the following section I will shortly present two of the rhetorical practices of argumentation. As a first rhetorical practice I will explain denying competence. Interactants mutually have to attribute competence for the global tasks of their interaction (see Nothdurft 1994). Competence is on the one hand a logically necessary condition, but on the other hand locally negotiable in detail by the interactants. To demonstrate competence provides validity to the discursive activities while denying competence withdraws trust in the partners’ utterances. By dealing with the criterion of competence speakers claim validity, make the partners’ claims problematic, or even reject them. Competence is seldom a central focus in argumentation but it is an important criterion for judging. Dealing with competence therefore is a referring and a pivotal activity: it refers to an activity of the speaker or his partners, and it regularily paves the way for the speaker’s following own activities.

Denying competence refers to personal qualities like age, job, social role, discursive abilities, and so on. Sometimes interactants critizise problematic, deficient, or irrelevant competences of their partners, sometimes they say that their partners have no competence at all. Problematic or even „wrong“ could be a competence which is related to personal interest (for example, if a manager of the tobacco industry defines the dangers of smoking cigarettes; for the other qualities of incompetence as deficient, irrelevant or not existing you may simply build examples of your own.

A denial of competence is uttered when speakers explicitly reserve some competence only for their own, or if the partner’s arguments implicitly make claims for competence. The rhetorical practice of denying competence is rather seldom in argumentation because it is a face-threatening activity. But sometimes in interactions before an audience, denying competence makes sense for the critic as a demonstrative act directed to the audience.

Denying competence as an argument practice is a powerful resource to block the partner’s move and to establish one’s own activities. It is dysfunctional if the face-threatening aspect overwrites the focal interactive tasks.

As a second example I will explain a practice by which the speaker claims a particular epistemic modality for his own activities: claiming factuality. In argumentation the common view on reality is fragile, there is dissent or uncertainty between the partners. Argumentants then try to reestablish a common perspective by making assertions with which they try to bring about acceptance by their partners. Assertions and their acceptance do oblige the interactants then to a common view.

Presupposing the possibility of such an agreement is a central premise for being able to interact at all. The interactive power of the epistemic mode of factuality is grounded in the assumption that other persons are able to perceive things like I do. Argumentants deal with this, but you have to notice that reality also is a discursively negotiable entity and not an objective entity that one can simply refer to.

The overwhelming part of argument activities in discourse deals with claiming factuality. Speakers regularily use agreements about aspects of reality to make clear and to consolidate their own argumentative positions or otherwise to undermine the partner’s position. The relations of all assertions thereby build up a network of a global position, they help to support other assertions and as a whole they make the discursive presentation itself scrutinizable, for example, via the probe of coherence and contradiction.

By claiming factuality the interactants try to interactively establish the validity of propositions and to push through their interest. Claiming factuality is normally realized by existential propositions. Such utterances are often self-evident and interactively ratified or even accepted in an unproblematic way. However, at the end of longer contributions, especially as conclusions, they are often rejected by partners because they claim global positions. Linguistically, the factuality mode is established by the indicative sentence mode. Lexically, you often find markers like „indeed“, „really“, or „literally“ and so on. Prominent also are some prosodic features which range from unmarked self-evidence to marking certainty by accent, pitch, and rhythm.

Claiming factuality always establishes the necessity to deal with it. Partners are forced to react either by ratifying or accepting, or by rejecting it. Accepting on the one hand then obliges partners for the further discourse while rejecting leads to a – normally dispreferred – expansion.

The interactive constraint to deal with this practice by ratifying, accepting or rejecting produces its own rhetorical power: Every claim stabilizes an argumentative position of the respective speaker. With it, aspects of a supposed reality are interactively publicized and asserted, and the inferential implications produce local and global effects. But the speaker himself is also bound by his or her own statements, and, besides, such assertions and their respective global position always are threatened by contradicting claims of their partners.

NOTES

i. The corpus reperesents a selection from the corpora of the Institute for German Language, which include some hundred natural conversations.

REFERENCES

Deppermann, A. (1997). Glaubwürdigkeit im Konflikt. Rhetorische Techniken in Streitgesprächen. Frankfurt et al.: Peter Lang Verlag.

Garfinkel, H. & H. Sacks (1970). On formal structures of practical actions. In: Y.S. McKinney & E.A. Tiryakian (Eds.), Theoretical sociology. New York: 337-366.

Kallmeyer, W. (Ed.)(1996). Gesprächsrhetorik. Rhetorische Verfahren im Gesprächsprozeß. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

Kallmeyer, W. & F. Schütze (1976). Konversationsanalyse. Studium Linguistik 1, 1-28.

Kallmeyer, W. & F. Schütze (1977). Zur Konstitution von Kommunikationsschemata der Sachverhaltsdarstellung. In: D. Wegner (Ed.), Gesprächsanalysen. (pp. 159-274), Hamburg: Buske Verlag.

Nothdurft, W. (1994). Kompetenz und Vertrauen in Beratungsgesprächen. In: W. Nothdurft, U. Reitemeier, P. Schröder (Eds.), Beratungsgespräche. Analyse asymmetrischer Dialoge (pp. 184-229), Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

Spranz-Fogasy, T. & T. Fleischmann (1993). Types of dispute courses in familiy interaction. In: Argumentation. An International Journal on Reasoning 7, 221-23.