To the memory of Theodoor Jan Krabbe (1941-1996) [i]

To the memory of Theodoor Jan Krabbe (1941-1996) [i]

1. Introduction: The Self-Gratulatory Argument

There can be no doubt that this is a perfect morning for the study of quasi-logical arguments. Otherwise, to say it bluntly, our hosts wouldn’t have put it on the program. Or would it be quasi-logical to say so? Anyhow, quasi-logical arguments are what’s up, and I’m much honored that you have all come to join me in this enterprise.

Of lectures on the quasi-logical there are exactly two types, either they are long or else they are short. Fortunately, I hate long lectures. This is fortunate for you, but also for me. Why may I rejoice in my own abhorrence of lengthy lectures? Well, that can be argued thus: suppose I liked long lectures, then I would certainly give one right now and be bound to hearing it out; but to hear my own long lecture would be a bad thing, since I happen to hate long lectures. So am I ever happy to hate long lectures!

That was an argument. Was that a quasi-logical argument? Yes, it was. It was meant to give you a taste of the quasi-logical, that is, to put it briefly, of a style of reasoning that unwarrantedly takes on the trappings of logical or mathematical rigor.[ii]

So, if this was a quasi-logical argument, what is its dialectic? Now wait. Give me a break. We’ll get to that later. It is certainly my intention in this lecture to show some of the dialectic of this argument; that is to expound in a profile of dialogue some of the moves and countermoves available to its discussants. But first I want to turn logic against quasi-logic and offer a logical analysis of this quasi-logical argument. Later on, I hope to show that such a logical analysis provides part of a profile of dialogue; that it constitutes part of the dialectic, but not all of it.

What would a logical analysis of the long lecture argument amount to? Generally, a logical analysis of an argument consists of two parts: a reconstruction and a critical evaluation. To reconstruct the argument, we notice that the argument gives the impression of being tightly reasoned and logical. We therefore try to reconstruct it as a logical derivation.[iii] One thing we need to attend to is the occurrence of a suppositional subargument that needs to be put into a more explicit format. As a first line of proof one may enter:

(1) I hate to hear long lectures.

(This may, in context, be taken to constitute a fact.)

As an unexpressed (and unproblematic) premise we may add:

(2) For all X, if I hate X, X is a bad thing for me.

And from this we may conclude:

(3) Hearing a long lecture is a bad thing for me.

As another unexpressed, empirical but, I think, unproblematic premise we may state:

(4) Whatever type of lecture I like, I get to hear it.

Then the argument introduces a supposition:

(5) Suppose: I like long lectures.

Given this supposition we may conclude, using (4):

(6) I get to hear a long lecture.

Whence, by (3) (maintaining the supposition):

(7) I get what is a bad thing for me.

By conditionalization we may retract the supposition to obtain:

(8) If I liked long lectures, I would get what is a bad thing for me.

For the sake of argument, let us pretend that the following premises are also acceptable:

(9) If I liked long lectures, that would do me no good.

(10) On account of my dislike of long lectures, no evil will befall me.

Thus, on balance, if I liked long lectures things would get worse as compared to my present state of dislike of them. Hence, let us presume that the calculus of rational sentiments now warrants the conclusion:

(11) I may be glad not to like long lectures.[iv]

One may expand the reconstruction so as to reach the conclusion that “I may rejoice in hating long lectures”, but the weaker conclusion will do. Passing to the evaluation stage, we first notice that the argument is less of an innocent conundrum than it might have been supposed.

What is worrying about the argument is its generalizability to a type: self-gratulatory argument. Given the present analysis, it seems that for all matters where choice is ethically neutral, a matter of taste, we have, no matter our predilections, special reason to be glad to have exactly those preferences we happen to have. If you hate red funiture, you should be glad that you hate red furniture.

Otherwise, you might have been buying loads of red furniture; and you so much hate the stuff! Yet the same holds for those that love red furniture: they have reason to rejoice in their preferences as well. This looks terribly suspect; you’re OK and I’m OK. Can it be? One logician’s solution, given this analysis, would be to point at line (8):

(8) If I liked long lectures, I would get what is a bad thing for me.

This line is obtained from the preceding suppositional argument by the rule of conditionalization. But conditionalization does not warrant the modalities (“liked” and “would”) that were introduced at this line. A proper application of conditionalization yields instead:

(8*) If I like long lectures, then I get what is a bad thing for me.

This proposition, which, by the way, follows immediately from premise (1), is much weaker. It is too weak to carry the rest of the argument. To reach the verdict that I may rejoice in my dislike of long lectures one needs to have recourse to the original modal version that tells us that I would be worse off in counterfactual situations in which I liked long lectures.

Alternatively, if one wants to save the full modal version of (8), one needs a modalized version of suppositional argument to support it. In a modalized suppositional argument reference to the preceding nonmodal part may be blocked. There are two such references: use is made of (3) and of (4). The use of (4) might be saved by giving this premise a modal formulation:

(4*) Whatever type of lecture I might like, I would get to hear it.

This modalized version of the premise will certainly not be canceled by the introduction of the counterfactual supposition that I like long lectures. The use of (3), however, cannot be saved in this way. In order to establish the following proposition:

(3*) Whatever type of lecture I might like, hearing a long lecture would be a bad thing for me.

One would have to push up the modalization to its premises (1) and (2). For (2) this may be unproblematic but the modalization of (1) yields a problematic premise:

(1*) Whatever type of lecture I might like, I would hate to hear long lectures.

This is problematic, for its seems plausible that if I liked long lectures I would not hate to hear them.

Thus, following the gist of this logical analysis, it seems that the argument goes wrong somewhere, but we cannot tell for sure where it goes wrong. Now this result is not really spectacular: one could have suspected beforehand that something was rotten. What the logical analysis adds is a more precise insight in the ways the argument goes wrong; or better, in the ways it might go wrong. Proposition (8) must be either modalized or unmodalized. If it is unmodalized the trouble arises in the last part of the argument. If it is modalized then either the suppositional part must be modalized as well, or the application of the rule of conditional proof would be in error. Then, if the suppositional proof is modalized, one needs to modalize (3) to avoid a fallacious reference in the now modalized suppositional proof. Finally, if (3) is modalized one needs to modalize premise (1) to restore validity in the first part of the argument. But this leaves us with a problematic premise.

From the logical analysis one may extract a pattern of dialectic moves and countermoves, a kind of profile of dialogue. Together these moves determine a strategy for the critic of the self-gratulatory argument. First, corresponding to the reconstruction part of the logical analysis, the critic must try to get to an agreement on a more precise understanding of the argument. In this phase the critic may ask the proponent to reformulate parts of the argument in a clarifying way, but she may also, more actively, propose reconstructions of her own. Of course, this dialectic process may lead to an understanding of the self-gratulatory argument different than the present reconstruction. In that case the rest of the dialectical process will also be quite different from what follows. But let us assume that an agreement on the present reconstruction can be obtained. Corresponding to the evaluation part of the logical analysis, the critic should then, in the second phase, go on to ask whether proposition (8) is to be understood as modalized or as unmodalized. If the answer is that it is to be understood as unmodalized, then the critic is to turn to criticism of the last part of the argument. If the answer is that it is to be understood as modalized, then she should point out that the suppositional part of the argument must be understood as modalized as well. Once this much has been granted she may go on to push the modalization upward over (3) to (1). Finally the critic may point out that the modalized version of (1) is highly problematic.[v]

We would not speak of a quasi-logical argument if we did not think there was something wrong with it, and this presentiment, in the present case, was borne out by the strategy displayed. Without going as far as to claim that we here have a winning strategy for the critic of the self-gratulatory argument (for one thing, we did not check on other possible reconstructions), there can be no doubt that the proponent of that argument gets driven into a corner from which it is hard to escape. Such a strategy I shall call a strong critical strategy (namely, a strong strategy for the critic).

Using a strong critical strategy against a quasi-logical argument will most likely put the proponent at fault. But the strategy need not tell which particular step in the argument is the one to blame. Generally, in a particular discussion, a tournament, in which the critic uses the strategy, the fault will be pinpointed at a particular spot. But then it can hardly be said that the fault was there to start with; rather it seems that the fault was constructed to be right there by the outcome of the dialectical process. The situation is quite analogous to that so aptly described by Richard Whately as he points out the indeterminate character of some fallacies. These are situations where a fallacy has been committed, but you cannot tell which fallacy it is.[vi]

To sum up the lessons drawn from this first example: a language user confronted with a quasi-logical argument is not without means of defense. In order to convince her adversary that his argument fails, she may solicit reconstructions of the argument and offer reconstructions herself, until a picture is obtained that is sufficiently clear to pursue a strategy of detailed criticism and evaluation. In this type of defense the critic generally goes beyond the stance of pure critical doubt to engage herself actively in discussing merits and demerits of parts of the argument. Thus part of the profile of dialogue associated with quasi-logical arguments consists of these two types of moves: the reconstructive and the evaluative.

2. The New Rhetoric’s Idea of the Quasi-Logical

What may be surprising, or even disquieting, is that in stressing the importance of applied logic the present approach might seem to run counter to that of The New Rhetoric. Since The New Rhetoric constitutes the locus classicus for the concept of quasi-logical arguments, and since I have no intention of belittling my indebtedness to Perelmans and Olbrechts-Tyteca, it will be proper to shortly investigate the New Rhetoric’s notion of the quasi-logical and to see where the differences lie between their approach and mine. According to The New Rethoric, quasi-logical arguments avail themselves of techniques of formal demonstration in a context of informal argumentation. I quote the beginning of its chapter on quasi-logical arguments (translation in the notes):

Les arguments que nous allons examiner dans ce chapitre prétendent à une certaine force de conviction, dans la mesure où ils se présentent comme comparables à des raisonnements formels, logiques ou mathématiques. Pourtant, celui qui les soumet à l’analyse perçoit aussitôt les différences entre ces argumentations et les démonstrations formelles, car seul un effort de réduction ou de précision, de nature non-formelle, permet de donner à ces arguments une apparence démonstrative; c’est la raison pour laquelle nous les qualifions de quasi logiques. (1970: Section 45, p. 259)[vii]

One more quote brings out a characteristic feature of many quasi-logical arguments:

… l’accusation de commettre une faute de logique est, elle-même, souvent, une argumentation quasi logique. On se prévaut, par cette accusation, du prestige du raisonnement rigoureux. (1970: Section 45, p. 260)[viii]

The authors discuss several ways in which the exploitation of formal demonstration in a context of informal argumentation can be accomplished. For instance, the arguer may present as a formal contradiction what is merely an informal, perhaps a pragmatic, incompatibility.[ix]

As a second example, I mention the informal division of a domain, which may be exploited, quasi-logically, as a basis for a completely rigorous constructive or destructive dilemma.[x]

Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca also discuss several means to fend off these quasi-logical arguments. Thus, where the claim is to have shown up a formal contradiction, one may try to show that it is merely a matter of incompatibility, that is, that one’s opponent has reduced or simplified the meaning of some statements in order to assimilate the system under attack to a formal system.[xi] In the case of a quasi-logical dilemma, they point out the possibility of converting it into a counterdilemma; this would amount to answering a quasi-logical argument by a quasi-logical argument. But they also mention a method of more general application that allows the critic to deconstruct a dilemma argumentatively: this method has the critic allege qualifications of time and other nuances that permit him, argumentatively, to slip between the horns of the dilemma (1969: 238; 1970, Section 56, p. 321).[xii]

The authors do not mention the possibility of detailed logical criticism, as embedded in a strong critical strategy, of a quasi-logical argument. It is not unlikely that in their view such criticism would be itself quasi-logical. On the other hand, at certain junctures they seem not to object to answering a quasi-logical argument by another one. So perhaps they would not object to the type of responses given in a strong critical strategy. Conversely, our profile of dialogue may be enriched by the inclusion of a branch that offers the Perelmanian option of answering a quasi-logical argument by a quasi-logical counterargument. The counterdilemma, for instance, may be looked upon as an invitation to retract the original dilemma without having to go through a detailed logical analysis of either dilemma. As such it is not unreasonable.[xiii]

Another type of move that is rightly stressed by Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca is that of introducing terminological clarifications and qualifications. These moves form an important part of the dialectic; we must assume them to be prominent in the discussion phase in our profile that corresponds to the reconstruction part of the logical analysis.

Yet another type of move is suggested by the aforementioned characterization of certain quasi-logical arguments as taking advantage of the prestige of rigorous thought. In as far as an arguer tries to intimidate his opponent by the use of vocabulary or other resources taken from logic and mathematics (or, for that matter, from any other prestigious field), where these resources have no real role to play, he may be charged with ad verecundiam. So we may add a move to the profile that introduces this type of charge.

Now that we have noted these valuable contributions, we should not refrain from mentioning two rather worrisome features of the account in The New Rhetoric. The first of these concerns the question whether quasi-logical arguments are ultimately to be evaluated negatively. And if so, whether ordinary logical deductive arguments, too, would have to be called quasi-logical in most cases. On these points The New Rethoric leaves us somewhat in the dark.[xiv]

On the view I want to defend, we can hold on to a distinction between the logical and the quasi-logical; the first being a positive and the second being a negative term of evaluation. But who is to decide whether an argument is logical or not?[xv]

The point of view I want to take on this question is an immanent dialectical one. That is, ultimately, the status of an argument must be decided in discussion, by the participants themselves. Dependent on that outcome the argument is reconstructed as valid, as doubtful, as erroneous, as a blunder, or even as a fallacy. An argument that is presented as deductive and logical may be reconstructed as logical or as quasi-logical, and in the latter case as doubtful, erroneous, or fallacious. But such predicates may also be applied to an untested, unreconstructed argument – an argument “on the hoof”, as John Woods would say (1995: 187). In this case they must be taken as a preliminary verdict by which the speaker indicates a presumption that, after having been reconstructed and discussed, the argument would most likely be thus designated. A preliminary verdict can be given by an outsider from a spectator’s perspective, or it can be given by a participant, before the show begins. In particular, the predicate “quasi-logical” indicates that the speaker, whether a spectator or a participant, presumes the profile of dialogue to contain a strong critical strategy.

From this point of view, there is no need to designate all arguments that make use of resources taken from logic or mathematics as “quasi-logical”. Some of these are far better designated as “logical”. The latter predicate, as used in a preliminary verdict, would indicate that the speaker expects the argument to prove its mettle when tested by a critical opponent. So these two predicates express different expectations as to what the profile of dialogue contains. It is true that on a abstract level the profiles of dialogue for logical and for quasi-logical arguments will contain the same types of move; but only the latter profiles will contain a strong critical strategy once specified.[xvi]

The second worrisome feature of the account in The New Rhetoric is that the authors base their treatment on a dichotomy between a realm of formal demonstration and a realm of informal argumentation.[xvii] As I see it, this whole dichotomy has been misconceived, whether we interpret “formal” as “formalized” or merely as “rigorous”. For reasons of time, I shall skip that part of my paper, which, as you may have noticed, stands in danger of presenting a quasi-logical dilemma.[xviii]

3. Are Quasi-Logical Arguments Fallacies?

Now that we have reviewed the treatment in The New Rhetoric, we may return to the construction of a profile of dialogue. But first I want to take up the issue of whether quasi-logical arguments are fallacies. The answer of course depends on one’s theory of fallacy, but if I were to survey them all this would become a long lecture, indeed. Let me therefore announce that in the present context I take fallacies to constitute transgressions of the rules of what may either be called “persuasion dialogue” or “critical discussion”. Acts that conform to the rules of dialogue, but are strategically inferior are not fallacies, but errors or blunders. The point of the distinction is that one may see it as a goal of critical discussion, subsidiary to its primary goal of conflict resolution, that the arguments that are put forward in it are critically tested. This means that in good dialogue both outcomes must be possible: sometimes an argument will pass all tests and sometimes an argument will fail. Consequently, putting forward a bad argument is not by itself a fallacy. It need not be unreasonable. Just as it is not by itself unreasonable to lose a discussion or a part of it, but only to fail to admit the dialectical consequences of one’s loss, so it is not by itself unreasonable to argue quasi-logically, but only to fail to admit that one has done so, once the flaw has been exposed.[xix]

4. A Profile of Dialogue

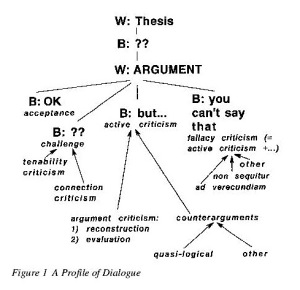

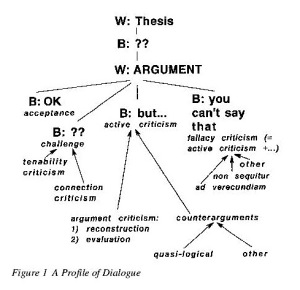

A profile of dialogue for quasi-logical and other arguments can now roughly be sketched as folows (see Figure 1). It is a profile that pertains to argument criticism in general; but, by means of an example, I hope to show presently how it may be applied to criticism of arguments that claim to be logically tight.[xx]

It is supposed that the argument is presented within a context of persuasion dialogue. Most simply, let there be two parties Wilma and Bruce. Suppose that Wilma has advanced a thesis and that Bruce has challenged this thesis and that Wilma has put forward an argument in order to defend her thesis. The argument can be either simple or complex. A simple argument contains only one premises/conclusion structure, a complex argument may contain a whole tree of such structures as well as suppositional parts.

I now want to see what dialectical moves should be available for Bruce to react to the argument. One reaction for Bruce would be to accept the argument as adequate and to retract the challenge. Other reactions are more or less critical.

The least critical of these other reactions would be to renew the challenge. Bruce may simply declare not to have been convinced by the argument. But in order that the dialectic process move forward, it is then incumbent upon Bruce to indicate precisely those steps in the argument that failed to convince him. This gives Wilma the opportunity to expand the argument precisely at those turns where expansions are required to achieve her particular goal in the dialogue, namely to convince Bruce. Notice that in the case of simple arguments this part of the profile reduces to moves of tenability criticism (are the reasons given themselves acceptable?) and of connection criticism (is the reason adequate to support the thesis?).

A number of more critical reactions for Bruce are grouped under the heading of active criticism. In these branches of the profile, Bruce takes upon himself a burden of proof to show that the argument, though perhaps not unreasonably proposed at this point of dialogue, is ultimately wrong, mistaken or insufficiently weak in some way or other. In this branch one finds counterarguments (including quasi-logical ones) and argument criticisms of various sorts.

Finally a third type of reaction for Bruce would be to put up a fallacy criticism. Bruce now denies that Wilma’s argument might be reasonable. On the contrary, it is claimed that the argument is inadmissible. That is, that it infringes such rules for persuasion dialogue (including rules of logic) as obtain in the company to which both disputants belong. The retraction Bruce is after is not the regular retraction that takes place on the ground level dialogue, but a retraction of the argument as an argument that never should have been put forward in the first place.[xxi]

5. An Example: The Immortality Argument

To fill out this rather sketchy profile a little further, let us contemplate another example. In it Wilma and Bruce discuss a proof of immortality that has often proved to be hard to disentangle. After each move I shall indicate its place in the profile.

Wilma: We, human beings, are immortal. [thesis]

Bruce: How come? [challenge]

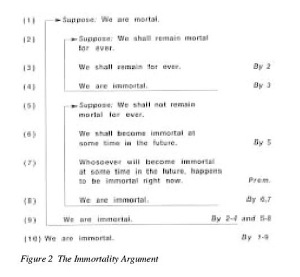

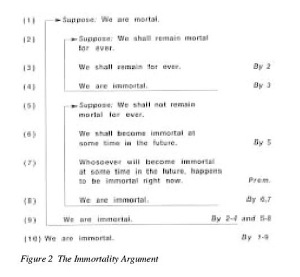

Wilma: This can be proved by sharp logical reasoning. For suppose we were mortal. In that case a good question to ask would be: shall we remain mortal? There are exactly two cases to consider: either we shall remain mortal for ever or we won’t. Suppose we shall remain mortal for ever. In that case we shall remain for ever. So in that case we must be immortal. On the other hand, supposing that we shall not remain mortal for ever, we must become immortal at some time in the future. But whosoever will become immortal at some time in the future, happens to be immortal right now. Consequently, both cases lead to the conclusion that we are immortal right now. The supposition that we would be mortal, therefore, has as a consequence that we happen to be immortal. From which we may conclude, by impeccable logic, that we must be immortal. [argument presented as “proof”: see Figure 2 for a survey]

Bruce: First of all I want to object to calling this argument a proof and to your calling your own logic impeccable. You have not indicated what special features would justify one to speak of a proof. For instance, you have not mentioned any axiomatic theory such that your argument would be a proof within the context of that theory. So, please, withdraw the claim to have provided a proof and admit that your logic still needs to be tested in critical discussion. [fallacy criticism: ad verecundiam]

Wilma: O.K. Let us call it an argument. [retraction of “proof”] But is there anything wrong with it? [upholding the argument]

Bruce: Let me see. Your argument sounds rather fishy. Many people will object to the last part, where, from the result that the supposition that we would be mortal leads to the consequence that we are immortal, you conclude that we are immortal. Your conclusion really seems conjured up out of a hat. But, fortunately for both of us, I studied enough logic to see there is nothing wrong with this last step. It is a reductio ad absurdum. So there must be some other mistake in your argument. Could I put my finger on a false dilemma? I suppose you realize that, for your case-splitting to be exhaustive, it must be presumed that we are either all equally mortal or all equally immortal? [active criticism: logical analysis, reconstructive phase]

Wilma: Yes. But alternatively one could replace the “we” in the argument by each of our proper names in turn: Frans, Rob, Tony, Charley, and so on. Thus the argument would show each of us, separately, to be immortal, and the case-splittings would all be safe. [alternative reconstruction]

Bruce: Uh, well, let us look at these cases. Aha! There you are! You say that if we shall remain mortal, we shall remain. The first “remain” is a linking verb, the second is an intransitive verb. That cannot be right! [active criticism: logical analysis, evaluative phase]

Wilma: Please pay attention to the thought rather than to the words. What I meant to say is that if we shall remain mortal for ever, that is, if we shall be mortal at any future point of time, then at any future point of time we must be there to be mortal. We can’t be mortal when we are dead. [back to reconstructive phase]

Bruce: I see. Now I’m confused. I thought to have spotted the flaw. But this was a kind of red herring in your argument, was it not? It looked like a flaw , but it wasn’t. I’d say your presentation is somewhat at odds with our rules of dialogue – the tenth rule of pragma-dialectics to be exact.[xxii] How can one pay attention to the thought if the words are jumbled? [fallacy criticism] Anyhow, I now grant the first horn of your dilemma. But in the second horn I think I can spot a problematic premise. You say that anyone who will become immortal at some time in the future, happens to be immortal right now. But take the case of Hercules, the ancient hero. At the end of his life he was adopted by the immortal gods; so during his life, as he was still a mortal being, it was true to say of him that he would become immortal at a certain time in what was then the future. But, before the gods granted him this great favor, he was not immortal yet. Wouldn’t that disprove your premise? [active criticism: counterargument]

Wilma: I’m sorry if my way of expressing has been misleading. Now as to the apotheosis of Hercules, you are right that there is a distinction to be made. On the one hand, “immortality” may be understood as an intrinsic property, such that for whoever has the property dying is impossible. This was the property the gods conferred on Hercules. But I meant “immortality” to be understood as an extrinsic property, that is, simply as the property one has if one will, in fact, live forever (even though death may in all eternity remain an unrealized possibility). Now if at some time in the future one of us has the property of living at that time and forever after, he or she must necessarily live through all moments of time from the present moment onwards. That is, that person must right now be immortal in the extrinsic sense. [back to reconstructive phase]

Bruce: I never was aware of this ambiguity in the meaning of “immortal” But the distinction seems almost evident now that we have delved so deeply into this argument. Yes, I suppose I can see it your way. [idem]

Wilma: Since now you have checked all parts of the argument, isn’t it about time to get to the concluding stage of this discussion as well as of this rather lengthy lecture in which our discussion is embedded? Are you prepared to withdraw your critical doubt with respect to my thesis? [walks to the door as she is getting to the concluding stage]

Bruce: Now wait a minute! If your thesis is right and we are immortal, there is plenty of time, so why hurry? [ad hominem: you don’t practise what you preach]

Wilma: Because you cannot beat my argument, dumbo. [abusive ad hominem]

We must leave Bruce and Wilma right in the middle of this altercation which, by the way, provides us with a clear-cut example of a dialectical shift.[xxiii] After all, I hate long lectures.

Figure 1 A Profile of Dialogue

6. Summary and conclusions

Summing up: In this lecture I wanted to discuss the dialectical moves that are appropriate in a critical discussion of a quasi-logical argument. Two examples of quasi-logical arguments have been presented for the purpose: the self-gratulatory argument and the immortality argument. Though the dialectical analysis of both of them had to be rather sketchy, I hope to have raised some interest in the dialectical study of arguments by means of the specification of profiles of dialogue. Ultimately, as I see it, the study of profiles is to help us construct rigorously formulated systems of formal dialectics (as in Walton and Krabbe 1995: Ch. 4); but I have not touched upon these. In the present case of quasi-logical arguments the dialectic was seen to link up closely with logical analysis, from which strong critical strategies could be derived, but we have also profited from the rhetorical point of view expounded in The New Rhetoric.

Adhering to the pragma-dialectical concept of fallacy, I did not want to say that all quasi-logical arguments are fallacious. Moreover, I did not envisage a theory of dialogue that would in all cases be able to decide on such matters as quasi-logicality or fallaciousness beforehand. In many cases, the theorist will have to refrain from anything more than a preliminary judgment. According to the immanent dialectical approach it must often be left to the disputants themselves to decide these matters. But their decision is not arbitrary. In their discussions the disputants are supposed to be guided by rules of dialectics that are accepted by the company of discussants to which they belong. The empirical and normative study of these rules is the task of the dialectician.

NOTES

[i] The present paper contains the literal text of my ISSA-conference keynote, read on June 18th, 1998. I hope the reader will be willing to excuse a number of peculiarities of style which are due to its having been written for the ear rarther than for the eye. Some notes, references, captions, and figures have been added. A summary of the paper is contained in the last two paragraphs. I want to thank the board of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (ISSA) for their invitation; my Groningen colleagues of the Promotion Club Cognitive Patterns (PCCP), who were the victims of a first try-out presentation, for a number of helpful suggestions; and David Atkinson for some prompt and apposite linguistic advice. Finally, I dedicate this piece to the memory of my brother, Theo, with whom I first invented and discussed the argument for immortality.

[ii] This rather sketchy definition is, I think, all that is needed to delineate my topic. The term ‘unwarrantedly’ introduces a normative element to be fleshed out from various perspectives.

[iii] Whether one is a deductivist or not, this way to reconstruct an argument seems perfectly legitimate when the mode of presentation of the argument invites us to see it as a rigorous deduction.

[iv] I doubt whether anything like a satisfactory ‘calculus of rational sentiments’ exists, but, anyhow, some sentiments are deemed more reasonable than others in certain contexts. We argue about these things with an – often implicit – appeal to “feeling rules” (Hochschild, 1979). As Arlie Hochschild wrote: In common parlance, we often talk about our feelings or those of others as if rights and duties applied directly to them. For example, we often speak of “having the right” to feel angry at someone. Or we say we “should feel more grateful” to a benefactor. We chide ourselves that a friend’s misfortune, a relative’s death, “should have hit us harder,” or that another’s good luck, or our own, should have inspired more joy. We know feeling rules, too, from how others react to what they infer from our emotive display. Another may say to us, “You shouldn’t feel so guilty; it wasn’t your fault, You don’t have a right to feel jealous, given our agreement.” (p. 564) One may agree with this idea – that we can discuss the rationality, or the appropriateness, of emotions, sentiments, or feelings – without committing oneself to the view that emotions are judgements (Solomon, 1980). The rationality of emotions as patterns of salience has been

discussed by Ronald de Sousa (1980).

[v] If the proponent of the original argument refuses to move along with these latter criticisms, say if he holds on to a step that derives a modalized from an unmodalized proposition, the critic may need to go into detail to demonstrate the invalidity of that particular step. Here she may have recourse to several methods in order to convince the proponent: counterexample, logical analogy, and formal analysis. In some cases, if the proponent can be held to certain rules of logic on account of which the invalidity should have been obvious, he may be brought to admit to have committed a fallacy (cf. my 1995). We shall get back to fallacies later.

[vi] Whately writes: if a man expatiates on the distress of the country, and thence argues that the government is tyrannical, we must suppose him to assume either that ‘every distressed country is under a tyranny,’ which is a manifest falsehood, or, merely that ‘every country under a tyranny is distressed,’ which, however true, proves nothing, the Middle Term being undistributed. (1836: 149-50) According to Whately, a fallacy has been committed, but you cannot tell which fallacy it is.

[vii] Translation: The arguments we are about to examine in this chapter lay claim to a certain power of conviction, in the degree that they claim to be similar to the formal reasoning of logic and mathematics. Submitting these arguments to analysis, however, immediately reveals the difference between them and formal demonstrations, for only an effort of reduction or specification of a nonformal character makes it possible for these arguments to appear demonstrative. This is why we call them quasi-logical. (Perelman and Olbrecht-Tyteca 1969: 193)

[viii] Translation: … the charge of having committed a logical error is often itself a quasi-logical argument. By making this charge, one takes advantage of the prestige of rigorous thought. (1969: 194)

[ix] Thus the arguer may pretend to have given a proof by the celebrated logical pattern of reductio ad absurdum, whereas he has done no more than raise some objections that might be answered.

[x] Thirdly, informal definitions that cover terminological manipulations may be presented as formal stipulations without theoretical content which, moreover, are taken to warrant unscrupulous substitutions by Leibniz’s Law.

[xi] Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca write: Aussi, un des moyens de défense qui sera opposé à l’argumentation quasi logique faisant état de contradictions sera de montrer qu’il s’agit non de contradiction mais d’incompabilité, c’est-à-dire que l’on mettra en évidence la réduction qui seule a permis l’assimilation à un système formel du système attaqué, lequel est loin de présenter, en fait, la mème rigidité. (1970, Section 46, p. 263) Translation: Therefore one of the means of defense to be used against the quasi-logical argument which claims a contradiction is to show that it is not a matter of contradiction but of incompatibility. In other words, one will display the reduction which alone has made possible the likening to a formal system of the system under attack, which in fact does not exhibit the same rigor. (1969: 196).

[xii] As to the example of Note 10: Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca do not explicitly discuss any techniques to ward off uncongenial definitions (except for the somewhat dubious charge of tautology), but it is clear that they consider definitions as argumentative, and therefore in principle as a proper focus for critical objections in a context of informal argumentation.

[xiii] This is not to say that, in critical discussion, it could be reasonable to negotiate and to ‘trade off dilemma’s’. Rather the counterdilemma is an expedient to convince the other party that the original dilemma does not hold water.

[xiv] On the one hand quasi-logical arguments are not officially designated by any negative terms such as ‘error’, ‘flaw’, or ‘fallacy’, and neither would one expect such a verdict from The New Rhetoric. On the other hand the term ‘quasi-logical’ by itself has a negative ring, and in discussing such arguments the authors strike a particularly critical note. An argument’s claim to be similar to the formal reasoning of logic and mathematics would hardly ever be justified. This leaves us wondering. A situation that is aggravated by the rather puzzling fact that many examples in The New Rhetoric are based on valid logical schemata such as the constructive dilemma, be it that their application remains somewhat doubtful. This makes one wonder whether there is any distinction between ordinary logical deductive arguments and quasi-logical arguments.

[xv] For an argument to be designated as quasi-logical, it is not sufficient that its mode of reasoning be taken from logic or mathematics. As stated in the introduction, it must also be the case that the transfer is ‘unwarrented’. But who decides whether this is the case or not?

[xvi] On an abstract level, a profile of dialogue, as in Figure 1, merely shows what possible types of moves are available for the disputants. Once the general scheme has been applied to a specific thesis, one obtains a survey of possible specific moves, from which strategies for either party may be selected.

[xvii] This dichotomy might explain the authors’ resistance to the idea of admitting a group of arguments that are plainly logical and not quasi-logical. So-called plainly logical arguments, they might want to say, would illegitimately treat a context of informal argumentation as if it were a context of formal demonstration.

[xviii] Braving such risks, I here present the argument that had to be skipped: The core of the trouble lies in the concept of “formal demonstration”. On the one hand “formal demonstration” may be taken to refer to formalized axiomatic deductions, that is, deductions in a formal language using a fixed set of rules of inference. But the construction of formal languages and formal deductions is much too specialized an activity for it to have such an impact on informal argumentation as Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca ascribe to formal demonstrations. For one thing, it is not the formalization of logic and parts of

mathematics that is responsible for the prestige of rigorous thought. Nor do the ideas of contradiction, definition, identity, dilemma, etc. originate from these formal systems. Also, if formalized axiomatic deductions were the standard that quasi-logical arguments exploit, it would remain a mystery how there could have been quasi-logical arguments before Frege.

On the other hand, one may interpret “formal demonstration” as “rigorous demonstration” or “proof”. Then we get to a concept of formal demonstration that very well explains the ad verecundiam character of many quasi-logical arguments. This is something to be aware of, and Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca were right to stress it. But there is simply no dichotomy. Logical and mathematical proofs are just one of a kind with informal arguments. Proofs cannot be taken as absolutes: what counts as a proof for one person may not count as a proof for someone else. To call an argument a proof announces a surplus value above the more mundane types of informal argument, such as being part of an (informal) axiomatic set-up, but the character of this surplus value may vary in different contexts. (This is explained more fully in my 1997.) In some cases the label “proof” may just constitute an ad verecundiam or ad baculum ingredient of one’s argument. Thus, what is presented as a rigorous proof is a potential object of analysis, of reconstruction and evaluation. In this proofs do not differ from other types of informal argumentation. Misuse of what appears to be schematically correct schemata is not excluded in the area of demonstration, as is witnessed by the logical paradoxes and the existence of flawed proofs. We may conclude that if “formal demonstrations” are interpreted as rigorous (but informal) proofs, quasi-logical arguments could occur just as well within the context of formal demonstrations as in the context of juridical, philosophical or everyday argumentation. Hence it would be impossible to explain quasi-logical arguments as attempts to emulate formal demonstrations in a context of informal argumentation. Thus either interpretation of the term “formal demonstration” lands us in difficulties. This poses a (hopefully not quasi-logical) destructive dilemma for the whole idea of basing the concept of quasi-logical argument on a dichotomy between informal argumentation and formal demonstration.

[xix] The cases where quasi-logical arguments are fallacies are those that may be shown to fulfill some extra conditions, among which figures pre-eminently that they must transgress the operative rules of dialogue. Which quasi-logical arguments are fallacies depends, then, on the rules of dialogue that hold in the context.

[xx] Profiles of dialogue are tree-shaped descriptions of options and possible sequences of moves in reasonable dialogue. Here “reasonable” does not imply that no fallacies are committed, but that fallacies and challenges of fallacies are adequately handled within the dialogue. The method of profiles aims at getting a survey of all the different ways a reasonable dialogue of some type could proceed. It was applied by Douglas Walton in his discussions of the fallacy of many questions (1989a: 68, 69; 1989b: 37, 38) and in several of his later books on fallacy theory (1995: 22-26; 1996: 150-54; 1997: 253-55). Cf. also my 1992 and 1995.

[xxi] The subject of retraction is a tricky one. Surely, one should admit reasonable retractions: retractions of fallacious moves of course, but also ground level retractions, say of standpoints a disputant has been unable to defend in a satisfactory way. On the other hand, persistent retraction of each of one’s commitments in dialogue would make reasonable discussion all but impossible. The problem of where and how to draw the line is one of the main themes in Walton and Krabbe 1995.

[xxii] ‘… Rule 10 for a critical discussion runs as follows: A party must not use formulations that are insufficiently clear or confusingly ambiguous and he must interpret the other party’s formulations as carefully and accurately as possible.’ (Van Eemeren and Grootendorst, 1992: 196)

[xxiii] In fact, Bruce’s tu quoque and Wilma’s abusive ad hominem secured them a fast cascading down into a quarrel. See Walton and Krabbe 1995, Sections 3.3 and 3.4, esp. pp. 105-7 and 111-12. A closer look at Proposition 6 (Figure 2) would have been more profitable

REFERENCES

De Sousa, Ronald (1980). The Rationality of Emotions. In: Amélie Oksenberg Rorty (ed.), Explaining Emotions, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, pp. 127-51, Ch. 5.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell (1979). Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure. American Journal of Sociology 85 (3), 551-75.

Krabbe, Erik C.W. (1992). So What? Profiles for Relevance Criticism in Persuasion Dialogues. Argumentation 6, 271-83.

Krabbe, Erik C.W. (1995). Can We Ever Pin One Down to a Formal Fallacy? In: Frans H. van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, J.

Anthony Blair and Charles A. Willard (eds.), Proceedings of the Third ISSA Conference on Argumentation (University of Amsterdam, June 21-24, 1994) II: Analysis and Evaluation, Amsterdam: Sic Sat, International Centre for the Study of Argumentation, pp. 333-344. Also in: Theo A. F. Kuipers and Anne Ruth Mackor (eds.), Cognitive Patterns in Science and

Common Sense: Groningen Studies in Philosophy of Science, Logic, and Epistemology, Amsterdam and Atlanta GA: Rodopi, 1995, pp. 151-64, and in: Johan van Benthem, Frans H. van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst and Frank Veltman (eds.), Logic

and Argumentation, Amsterdam, etc.: North-Holland, 1996, pp. 129-141.

Krabbe, Erik C.W. (1997). Arguments, Proofs, and Dialogues. In: Michael Astroh, Dietfried Gerhardus, and Gerhard Heinzmann (eds.), Dialogisches Handeln: Eine Festschrift für Kuno Lorenz, Heidelberg: Spektrum, Akademischer Verlag, pp. 63-75.

Perelman, Chaïm and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969). The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation (Translation by John Wilkinson and Purcell Weaver of Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, Traité de l’argumentation: La nouvelle rhétorique, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (2 vols.), 1958). Notre Dame, IN, and London: University of Notre Dame Press.

Perelman, Chaïm and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca (1970). Traité de l’argumentation: La nouvelle rhétorique, 3rd ed. Brussels: Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles. First edition: Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (2 vols.), 1958.

Solomon, Robert C. (1980). Emotion and Choice. In: Amélie Oksenberg Rorty (ed.), Explaining Emotions, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, pp. 251-81, Ch. 10.

Van Eemeren, Frans H. and Rob Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies. Hillsdale, NJ, Hove, and London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Walton, Douglas N. (1989a). Question-Reply Argumentation. New York, Westport, CT, and London: Greenwood Press.

Walton, Douglas N. (1989b). Informal Logic: A Handbook for Critical Argumentation. Cambridge, etc.: Cambridge University Press.

Walton, Douglas N. (1995). A Pragmatic Theory of Fallacy. Tuscaloosa, AL, and London: The University of Alabama Press.

Walton, Douglas N. (1996). Arguments from Ignorance. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Walton, Douglas N. (1997). Appeal to Expert Opinion. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Walton, Douglas N. and Erik C.W. Krabbe (1995). Commitment in Dialogue: Basic Concepts of Interpersonal Reasoning. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Whately, Richard (1836). Elements of Logic. New York: William Jackson. First edition 1826.

Woods, John (1995). Fearful Symmetry. In: Hans V. Hansen and Robert C. Pinto (eds.), Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings, University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 181-93, Ch. 13.

“There are some men. . . so wild and boorish in feature and gesture, that even though sound in talent and art, they cannot enter the ranks of the orators (Cicero 1942, 1988: 81).”

“There are some men. . . so wild and boorish in feature and gesture, that even though sound in talent and art, they cannot enter the ranks of the orators (Cicero 1942, 1988: 81).”