ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Argument Mediation For Lawyers: The Presentation Of Arguments

1. The logic of law

1. The logic of law

Most lawyers have some awareness of logic, although the awareness is normally limited. The logical connectives ‘… and …’ and ‘ … or …’ are known, and maybe even the ambiguous interpretation of a composite sentence of the form ‘a and b or c’ is familiar. Some might regard the connective ‘if …, then …’ as the abstract form of a legal rule and the rule of inference Modus Ponens as the general template of legal reasoning.

Why do lawyers pay so little attention to logic? The main problem is that logic in its classical appearances (such as propositional or predicate logic) is not sufficiently satisfying as a model of legal argument: it is too far from the argument forms that lawyers use in practice. In recent years, there has been a large amount of research on the development of logical tools for legal argument (see, e.g., the work of Gordon [1993, 1995], Hage [1997], Lodder [1998], Prakken [1993, 1997] and Verheij [1996]). Argument forms that have been studied include arguments concerning exceptions to rules, conflicts of reasons and rule applicability.

The logical tools that have recently been developed can be categorized under three headings: defeasibility, integration of logical levels, and the process character of argument [Verheij et al., 1997]. Defeasibility is a characteristic of arguments and, in a derived sense, of conclusions. A conclusion is defeasible if it is the conclusion of a defeasible argument. Defeat occurs if a conclusion is no longer justified by an argument because of new information. For instance, the conclusion that a thief should be punished is no longer justified if it turns out that there was a legal justification for the theft, such as an authorized command.

The integration of logical levels is for instance required if reasons are weighed. If arguments lead to incompatible conclusions, weighing of reasons is necessary to determine which conclusion follows. Additional information is necessary to determine the outcome of the weighing process. In some views, this information is on a higher logical level than the facts of cases, and the rules of law. However, since there can also be arguments about the weighing of reasons, the integration of levels is required.

The process character of argument also led to the development of new logical tools. For instance, the defeasibility of arguments cannot be separated from the process of taking new information into account. During the process of argumentation conclusions are drawn, reasons are adduced, counterarguments are raised, and new premises are introduced. In traditional models, only the end products of the process are modeled.

The focus has been primarily on the technical development of the logical tools, and only in the second place on their practical adequacy for modeling legal argument. Presently a convergence of opinions on the necessary logical tools takes shape, and a systematic practical assessment of the logical tools becomes essential. In the research reported on in this paper, a step towards the practical assessment is made by the development of two experimental computer systems for argument mediation for lawyers. In computer-supported argument mediation, one or more users of the system engage in an argument that is mediated by the system: the system administers the argument moves and safeguards that the rules of argument are observed. It can, if appropriate, give advice to the user.

A new problem for argument researchers, as posed by the development of systems for argument mediation is how arguments should be presented to the users of the system. In this paper, we describe two experimental computer systems, the Argue!-system and the Argumentation Mediator, each using a different way of argument presentation. The two systems are based on a simplified version of Verheij’s [1996] CumulA-model, which is a procedural model of argumentation with arguments and counterarguments.

Section 2 briefly discusses argument mediation and the two experimental systems of the present paper. In section 3, an example case of Dutch tort law is summarized, that will be used to illustrate the two systems of argument mediation. Section 4 contains an introduction of CumulA, the procedural model of argumentation with arguments and counterarguments, that underlies the two experimental systems. Section 5 and 6 contain sample sessions of the two systems. In section 7, the two systems are compared with each other and selected related systems, especially with regards to their underlying argumentation theories and user interfaces. Section 8 suggests a shift from argument mediation systems as theoretical to practical tools.[i]

2. Experiments with argument mediation

In the research on computer-mediated legal argument, computer systems are developed that can be used to mediate the process of argumentation of one or more users. The systems can mediate the process in which arguments are drafted and generated by the users, e.g., by

– administering and supervising the argument process,

– keeping track of the conclusions that are justified, and the assumptions that are made,

– keeping track of the reasons adduced and the conclusions drawn,

– keeping track of the counterarguments that have been adduced,

and

– checking whether the users of the system obey the pertaining rules of argument.

Recently several experimental systems for (legal) argument mediation have been developed (e.g., Room 5 by Loui et al. [1997], Zeno by Gordon and Karacapilidis [1997], and DiaLaw by Lodder [1998]). The systems differ on the user interfaces and on the underlying argumentation theory that is used.[ii]

A new problem for argument researchers, as posed by the development of systems for argument mediation is how arguments should be presented to the users of the system. In this paper, we describe two experimental computer systems, using different ways of argument presentation. The first, the Argue!-system, has a graphical user interface: the user of the system ‘draws’ argument structures, by clicking and dragging a pointing device, such as a mouse. The second, the Argumentation Mediator, has a template-based user interface: the user gradually constructs arguments, by filling in templates that correspond to argument patterns.

The two systems are based on Verheij’s [1996] CumulA-model, which is a procedural model of argumentation with arguments and counterarguments.

3. An example taken from Dutch tort law: the ‘bussluis’ case

To illustrate the two systems of argument mediation, we use an example taken from Dutch tort law. In Dutch tort law, the liability to repair damages on the basis of tort is determined in two steps:

Step 1. Determine the general duty to compensate damages on the basis of tort (art. 6:162 BW)

Step 2. Determine the relative amount of imputability in order to find the portion of the damages that has to be compensated (art. 6:101 BW)

For instance, assume that John has the general duty to compensate for certain damages, as suffered by Mary, on the basis of a tort committed by John. Assume also that the damages were partly due to Mary’s own fault. If the judge decides that the damages must be imputed to Mary for 25 %, John only has to compensate 75 % of Mary’s damages.

The logic of Dutch tort law enabled the somewhat surprising decision in the Dutch ‘bussluis’ case between a cab-driver and the local authorities (Dutch Supreme Court, March 20, 1992; Court of Justice of the Hague, September 15, 1994): although there was a general duty of the Municipality to compensate for the damages of the cab-driver, the actual portion of the damages that had to be compensated for was nil, because the damages were fully imputed to the cab-driver.

The reasoning can be summarized as follows:

Step 1. The Municipality had committed a tort against the cab-driver.

Therefore, the Municipality had the general duty to repair the damages (on the basis of art. 6:162 BW).

Step 2. The damages were fully imputed to the cab-driver. Therefore, the portion of the damages to be compensated for was nil (on the basis of art. 6:101 BW).

The case is discussed more extensively by Lodder and Verheij [1998] and Verheij and Lodder [1998].

4. CumulA: a model of defeasible argumentation in stages

CumulA [Verheij, 1996] is a procedural model of argumentation with arguments and counterarguments. It is based on two main assumptions. The first assumption is that argumentation is a process during which arguments are constructed and counterarguments are adduced. The second assumption is that the arguments used in argumentation are defeasible, in the sense that whether they justify their conclusion depends on the counterarguments available at a stage of the argumentation process.

The goal of argumentation is to (rationally) justify conclusions. In CumulA, the focus is on the process of argumentation, and on the defeasibility of the arguments used in argumentation. Argumentation is a process, in the sense that during argumentation arguments are constructed and counterarguments are brought up. Arguments are assumed to be defeasible, in the sense that if an argument at some stage of the argumentation process justifies its conclusion, it not necessarily justifies its conclusion at all later stages. The defeat of an argument is caused by a counterargument that is itself undefeated.

For instance, if the Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver, a conclusion would be that the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages. The conclusion can be rationally justified, by giving support for it. E.g., the following argument could be given:

The Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver.

So, the Municipality has the (general) duty to repair the damages.

So, the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages.

Recall that in Dutch tort law, the general duty to repair damages and the portion of the damages to be repaired are established consecutively.

An argument as above is a reconstruction of how a conclusion can be supported. The argument given here consists of two steps.

An argument that supports its conclusion does not always justify it. For instance, if in our example it turns out that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver (as in the ‘bussluis’ case), the conclusion that the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages would no longer be justified. The argument has become defeated. In the example, the argument:

The Municipality has the (general) duty to repair the damages.

So, the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages.

does not justify its conclusion because of the counterargument.

The damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver.

CumulA is a procedural model of argumentation with arguments and counterarguments, in which the defeat status of an argument, either undefeated or defeated, depends on:

(1) the structure of the argument;

(2) the counterarguments;

(3) the argumentation stage.

We briefly discuss each below. The model builds on the work of Pollock [1987, 1995], Loui [1991, 1992], Vreeswijk [1993, 1997] and Dung [1995] in philosophy and artificial intelligence, and was developed to complement the work on the model of rules and reasons Reason-Based Logic (see, e.g., Hage [1993, 1996, 1997] and Verheij [1996]).

In the model, the structure of an argument is represented as in the argumentation theory of Van Eemeren and Grootendorst [1981, 1987]. Both the subordination and the coordination of arguments are possible. It is explored how the structure of arguments can lead to their defeat. For instance, the intuitions that it is easier to defeat an argument if it contains a longer chain of defeasible steps (‘sequential weakening’), and that it is harder to defeat an argument if it contains more reasons to support its conclusion (‘parallel strengthening’), are investigated.

In the model, which arguments are counterarguments for other arguments is taken as a primitive notion [cf. Dung, 1995]. This is in contrast with Vreeswijk’s [1993, 1997] model, in which conflicts of arguments (i.e., arguments with conflicting conclusions) are the primitive notion. In CumulA, so-called defeaters indicate which arguments are counterarguments to other arguments, i.e., which arguments can defeat other arguments. It turns out that defeaters can be used to represent a wide range of types of defeat, as proposed in the literature, e.g., Pollock’s [1987] undercutting and rebutting defeat.

Moreover some new types of defeat can be distinguished, namely defeat by sequential weakening (related to the well-known sorites paradox) and defeat by parallel strengthening (related to the accrual of reasons).

In the CumulA-model, argumentation stages represent the arguments and the counterarguments currently taken into account, and the status of these arguments, either defeated or undefeated. The model’s lines of argumentation, i.e., sequences of stages, give insight in the influence that the process of taking arguments into account has on the status of arguments.

For instance, assume that John has the general duty to compensate for certain damages, as suffered by Mary, on the basis of a tort committed by John. Assume also that the damages were partly due to Mary’s own fault. If the judge decides that the damages must be imputed to Mary for 25 %, John only has to compensate 75 % of Mary’s damages.

To summarize, CumulA shows

(1) how the subordination and coordination of arguments is related to their defeat;

(2) how the defeat of arguments can be described in terms of their structure, counterarguments, and the stage of the argumentation process;

(3) how both forward and backward argumentation can be formalized in one model.

Verheij [1996] discusses the CumulA-model extensively, both informally and formally. The two argument mediation systems, discussed in this paper, have restricted versions of CumulA as their underlying argumentation theory.

5. The Argue!-system: a graphical interface

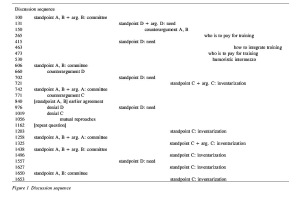

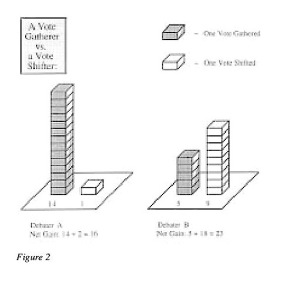

The first experimental implementation of CumulA is an argument mediation system with a graphical interface. It is referred to as the Argue!-system. The user ‘draws’ argument structures, by clicking and dragging a  pointing device, such as a mouse. We discuss an example session, based on the ‘bussluis’ case. As a start, a statement is typed, ‘The Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver’ (Figure 1).

pointing device, such as a mouse. We discuss an example session, based on the ‘bussluis’ case. As a start, a statement is typed, ‘The Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver’ (Figure 1).

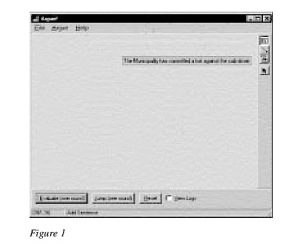

Statements can be justified by adding reasons (in the figure: ‘The Municipality has acted against proper social conduct’), and can be used to draw conclusions (‘The Municipality has the duty to repair the damages’). This is visually depicted in a straightforward way, by arrows connecting the statement-boxes (Figure 2).

The reader may have noticed that the statement ‘The Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver’ was first in a grey box, and now is in a white box. This is due to the different statuses that statements can have: if a statement is unevaluated it is in a grey box, if it is undefeated (i.e., justified), it is in a white box. In the example, the statement ‘The Municipality has acted against proper social conduct’ is undefeated, since it has been added as an assumption. The other two statements become undefeated since there is an undefeated reason for them.

The reader may have noticed that the statement ‘The Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver’ was first in a grey box, and now is in a white box. This is due to the different statuses that statements can have: if a statement is unevaluated it is in a grey box, if it is undefeated (i.e., justified), it is in a white box. In the example, the statement ‘The Municipality has acted against proper social conduct’ is undefeated, since it has been added as an assumption. The other two statements become undefeated since there is an undefeated reason for them.

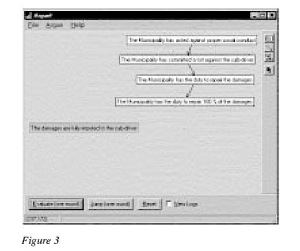

The line of argument continues in order to determine the amount of damages that the Municipality has to pay. At first, the conclusion is drawn that the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages. However, the user recalls something about the importance of imputability (Figure 3).

The statement that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver is a counterargument to the argument that the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages because the Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver. In order to indicate that one argument is a counterargument to another, a special visual structure is used (Figure 4).

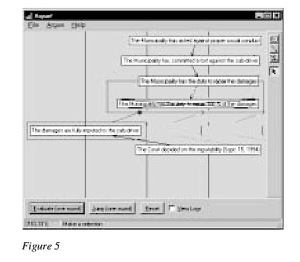

Since the statement that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver is as yet unevaluated, the statement that the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages is still justified. In order to justify the statement that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver, the relevant case is cited. Since the corresponding statement that the Court decided on the imputability, is added as a assumption, the conclusion that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver, becomes justified (Figure 5).

Since the statement that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver is as yet unevaluated, the statement that the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages is still justified. In order to justify the statement that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver, the relevant case is cited. Since the corresponding statement that the Court decided on the imputability, is added as a assumption, the conclusion that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver, becomes justified (Figure 5).

As a side effect, the statement that the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages, has become defeated (visually indicated by the cross in the corresponding box), since the argument that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver, now is a counterargument.

Now it is concluded that the Municipality has the duty to repair 0 % of the damages, on the basis of the reason that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver. If desired, the rule that warranted the connection between the reason and the conclusion, can be made explicit by the user of the system (Figure 6).

When the user has stated that the rule of art. 6:102 of the civil code determines the portion of the damages, the

session ends (Figure 7).

session ends (Figure 7).

6. The Argumentation Mediator: a template-based interface

The second experimental implementation of CumulA is a system for the mediation of argument with a template-based interface. It is referred to as the Argumentation Mediator. The user gradually constructs arguments, by filling in templates that correspond to argument patterns. We give an example session, again based on the ‘bussluis’ case. The opening screen of the implementation shows four ‘Argue’-buttons[iii], that give access to the available argument templates, and four ‘View’-buttons, that give different ways of viewing the current stage of argumentation stage (Figure 8). In the example session, the functionality of the buttons will be explained.

When the user clicks the ‘Statement’-button, a template for making a statement is shown (Figure 9). The user types the statement that the Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver. The statement can have be of two types, namely the query- and the assumption-type. A statement of query-type is a new issue[iv] of argumentation and no claim is made with regards to its justification status. Normally the goal of making a query-type statement is to determine whether it is justified. A statement of assumption-type is taken as justified ‘by assumption’ and does not require further justification. Normally the goal of making an assumption-type statement is to use it for justifying other statements (of query-type). In the example, the statement that the Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver, is of query-type, since the user wants to establish whether it is justified.

The result of the argument move is the following. The icon in front of the sentence ‘The Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver’ consists of a question mark, indicating that the corresponding statement is of query-type, and a (grey) circle, indicating that it is currently neither justified nor unjustified (Figure 10). Now the user clicks the ‘Reason/conclusion’-button to give a reason for the conclusion that the Municipality has committed a tort against the cab-driver (Figure 11).

Since reason that the Municipality has acted against proper social conduct is of assumption-type (indicated by the exclamation mark in its icon), the conclusion that the Municipality has committed a tort becomes justified, indicated by the (green) plus. Since the reason is of assumption-type it is also taken as justified (Figure 12).

Since reason that the Municipality has acted against proper social conduct is of assumption-type (indicated by the exclamation mark in its icon), the conclusion that the Municipality has committed a tort becomes justified, indicated by the (green) plus. Since the reason is of assumption-type it is also taken as justified (Figure 12).

The ‘Reason/conclusion’-template can of course not only be used for adducing reasons, but also for drawing conclusions. Below the user uses the statement that the Municipality has committed a tort as a reason to draw the conclusion that the Municipality has the duty to repair the damages (Figure 13).

From the reason that the Municipality has the duty to repair the damages the user draws the conclusion that the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of the damages (Figure 14).

The user recalls that the imputability of the cab-driver can diminish the amount of damages to be repaired. By clicking the ‘Exception’-button the user gets access to the exception-template. The user types the exception that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver, and selects the reason/conclusion it blocks (Figure 15).[v]

The result of the user’s exception move is that the conclusion that the Municipality has the duty to repair 100 % of  the damages is no longer justified, as indicated by the (red) cross (Figure 16).

the damages is no longer justified, as indicated by the (red) cross (Figure 16).

Although the exception that the damages are fully imputed to the cab-driver was an assumption, the user chooses to give a reason for it (using the reason/conclusion-template), namely that the Court decided on the imputability (Sept. 15, 1994). The type of the exception is changed to the query-type (Figure 17)

Finally, the user concludes that the Municipality has the duty to repair 0 % of the damages (Figure 18).

Until now, the session always showed the arguments that were constructed, since the ‘Arguments’-button of the ‘View’-panel was pressed. The other buttons of that panel give access to other information. For instance, the ‘Line of argumentation’-button gives access to the successive argument moves performed by the user (Figure 19).

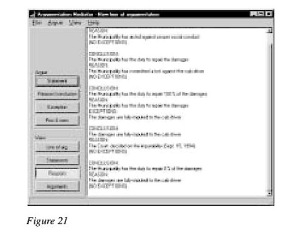

The ‘Statements’- and ‘Reasons’-buttons give access to the statements and the reasons (including the corresponding conclusions and exceptions) that have been entered by the user (Figure 20, 21).

7. A comparison of argument-mediation systems

In order to put the two discussed systems for argument mediation in context, they are briefly compared to three other systems, namely Room 5 by Loui et al. [1997], Zeno by Gordon and Karacapilidis [1997], and DiaLaw by Lodder [1998]. The system of section 5 is referred to as the Argue!-system, that of section 6 as the Argumentation Mediator. First, the underlying argumentation theories are discussed; second, the user interfaces.

7.1 The underlying argumentation theories

In the underlying argumentation theories of all five systems argumentation is dynamic. Statements can be made, and reasons can be adduced. In Room 5, Zeno and DiaLaw, argumentation is issue-based. No new conclusions can be drawn, since these systems focus on justification of an initial central issue. In the Argue!-system (section 5) and the Argumentation Mediator (section 6), argumentation is free, since there is no central issue, and allow both forward argumentation (i.e., drawing conclusions) and backward argumentation (i.e., adducing reasons).

All systems model a notion of defeasibility of argumentation. Room 5, Zeno and DiaLaw have a notion of reasons for and against conclusions.[vi] In Zeno and DiaLaw, weighing the conflicting reasons determines which conclusions are justified. DiaLaw, the Argue!-system and the Argumentation Mediator have an undercutter-type exception (see note 5). The Argue!-system models defeat by sequential weakening (see Verheij [1996, p. 122]): an argument is defeated since it contains an unacceptable sequence of steps.

Only DiaLaw has a notion of the rules underlying argument steps, as it is based on the theory of rules and reasons Reason-Based Logic (see, e.g., Hage [1996, 1997] and Verheij [1996]).

Only DiaLaw has a notion of the rules underlying argument steps, as it is based on the theory of rules and reasons Reason-Based Logic (see, e.g., Hage [1996, 1997] and Verheij [1996]).

In Room 5, Zeno and DiaLaw, argumentation is considered as a game with participants. In Room 5 and Zeno, the game character is left implicit, but obtained by the distributed access to the systems, on the World-Wide Web. In DiaLaw, the game character is made explicit in the form of a dialogue game with two parties. The Argue!-system and the Argumentation Mediator have no explicit notion of participants.

7.2 The user interfaces

Room 5, Zeno, the Argue!-system and the Argumentation Mediator present arguments in a visual manner. Zeno, the Argue!-system and the Argumentation Mediator use a tree-like presentation. Room 5 uses a clever system of boxes-in-boxes in an attempt to avoid ‘pointer-spaghetti’. In DiaLaw, and also in the Argumentation Mediator, argumentation is presented in a verbal manner, namely as a sequence of moves.

In Room 5 and Zeno, counterarguments (formed by reasons against conclusions) are grouped together in the visual argument structure. In the Argue!-system, counterarguments are shown by a special visual structure. In the Argumentation Mediator, counterarguments (currently only formed by undercutter-type exceptions) are visible in a special viewing window, namely the ‘Reasons’-view. In DiaLaw, counterarguments are not directly accessible.

In the Argumentation Mediator and DiaLaw, the dynamic aspect of argumentation is shown by a view on the sequence of moves. In Room 5, Zeno and the Argue!-system, only a view on the current stage of the argumentation process is visible. In Room 5 and the Argumentation Mediator, it is possible to switch between different views showing different types of information.

DiaLaw has a text-based interface; moves are typed at a command-prompt. The Argue!-system has a graphical interface: argument structures are ‘drawn’ using a pointing device. Room 5, Zeno and the Argumentation Mediator have a template-based interface: users fill in forms to perform an argument move. The Argumentation Mediator provides different forms for different moves to facilitate the user.

DiaLaw has a text-based interface; moves are typed at a command-prompt. The Argue!-system has a graphical interface: argument structures are ‘drawn’ using a pointing device. Room 5, Zeno and the Argumentation Mediator have a template-based interface: users fill in forms to perform an argument move. The Argumentation Mediator provides different forms for different moves to facilitate the user.

7.3 Conclusions

If we look at the above discussion, some conclusions can be drawn.

– An issue-based argument mediation system has the advantage that the process of argumentation has a focus, which can be useful, or even necessary (e.g., in a game-like situation). However, a system that is not issue-based (such as the two systems presented in this paper) adds flexibility, namely the possibility of forward argumentation.

– Current argument mediation systems have different notions of defeasibility. One should therefore strive for integration, or explicitly defend choices.

– A notion of rules should be included, or one should defend why it is not. Remarkably, none of the discussed systems with a visual, window-style interface has a notion of rules.

– Argument mediation systems with visual, window-style interfaces are obviously more user-friendly than text-based interfaces.

Among the visual interfaces, a template-based interface seems easier to use than a graphical interface (as in the Argue!-system), in which special visual structures have to be drawn. A system with different templates for different types of argument moves (as in the Argument Mediator) seems promising.

– The choice of argument moves that are available to the user, is crucial for user acceptance. A particular choice should not just be based on theoretical grounds, but must correspond to the needs of users.

8. Argument mediation systems for lawyers: from theoretical to practical tools

The recent advances in the theory of legal argument, especially with respect to defeasibility, integration of logical levels, and the process character of argument require a practical assessment. One way of such assessment is to build usable systems for argument mediation. In this paper, two experimental systems, namely the Argue!-system and the Argumentation Mediator, have been presented, and briefly compared to selected related systems, namely Room 5, Zeno, and DiaLaw. The differences between the underlying argumentation theories and user interfaces are striking, and show that argument mediation systems are still in their early stages of development. On the one hand, current argument mediation systems seem not yet sufficiently mature to be used as practical tools by practicing lawyers. On the other hand, they already turn out useful as theoretical tools, and help to enhance argumentation theory. The move from theoretical to practical tools will take serious effort, both by researchers and by system developers, but is manageable for the near future.

Acknowledgments

The author gladly acknowledges the financial support by the Dutch National Programme Information Technology and Law (ITeR) for the research reported in this paper (project number 01437112). He also thanks Arno Lodder and Jaap Hage for comments and discussion.

NOTES

[i] Sections 4 and 5 have been adapted from Lodder and Verheij [1998] and Verheij and Lodder [1998].

[ii] In the argumentation theories of all systems for argument mediation discussed in this paper, argumentation is considered defeasible. Systems based on classical logic, e.g., Tarski‘s World by Barwise and Etchemendy

(see http://csli-www.stanford.edu/hp/) are not discussed.

[iii] At the time of writing this paper, the ‘Pros & cons’-button does not yet give access to a template.

[iv] This is the terminology used in the Zeno-project [Gordon and Karacapilidis, 1997].

[v] The exception is of undercutter-type [Pollock, 1987], as it breaks the justifying connection between the reason and the conclusion. I slightly prefer to speak of exceptions to rules, and not to reasons, that arise from rules (see the work on Reason-Based Logic by Hage [1996, 1997] and Verheij [1996]). However, the current implementation does not give access to the rules behind reasons.

[vi] The ‘Pros & cons’-button of the Argumentation Mediator suggests it has a notion of reasons for and against conclusions. However, as yet, no corresponding functionality has been implemented (see note 3).

REFERENCES

Dung, P.M. (1995). On the acceptability of arguments and its fundamental role in nonmonotonic reasoning, logic programming and n-person games. Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 77, pp. 321-357.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Grootendorst, R., and Kruiger, T. (1981). Argumentatietheorie. Uitgeverij Het Spectrum, Utrecht.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Grootendorst, R. and Kruiger, T. (1987). Handbook of Argumentation Theory. A Critical Survey of Classical Backgrounds and Modern Studies. Foris Publications, Dordrecht. Translation of van Eemeren et al. (1981).

Gordon, T.F. (1993). The Pleadings Game. An Artificial Intelligence Model of Procedural Justice. Dissertation.

Gordon, T.F. (1995). The Pleadings Game. An Artificial Intelligence Model of Procedural Justice. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

Gordon, T.F., and Karacapilidis, N. (1997). The Zeno Argumentation Framework. The Sixth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law. Proceedings of the Conference, pp. 10-18. ACM, New York (New York).

Hage, J. (1993). Monological reason based logic. A low level integration of rule-based reasoning and case-based reasoning. The Fourth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law. Proceedings of the Conference, pp. 30-39. ACM, New York (New York). Also published as report SKBS/B3.A/93-08.

Hage, J. (1996). A Theory of Legal Reasoning and a Logic to Match. Artificial Intelligence and Law, Vol. 4, pp. 199-273.

Hage, J.C. (1997). Reasoning with Rules. An Essay on Legal Reasoning and Its Underlying Logic. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

Lodder, A.R. (1998). DiaLaw – on legal justification and dialog games. Dissertation, Universiteit Maastricht.

Lodder, A.R., and Verheij, B. (1998). Opportunities of computer-mediated legal argument in education. Proceedings of the BILETA-conference – March 27-28. Dublin, Ireland.

Loui, R.P. (1991). Ampliative Inference, Computation, and Dialectic. Philosophy and AI. Essays at the Interface (eds. Robert Cummins and John Pollock), pp. 141-155. The MIT Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts).

Loui, R.P. (1992). Process and Policy: Resource-Bounded Non-Demonstrative Reasoning. Report WUCS-92-43. Washington University, Department of Computer Science, Saint Louis (Missouri).

Loui, R.P., Norman, J., Altepeter, J., Pinkard, D., Craven, D., Lindsay, J., and Foltz, M. (1997). Progress on Room 5. A Test-bed for Public Interactive Semi-Formal Legal Argumentation. The Sixth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law. Proceedings of the Conference, pp. 207-214. ACM, New York (New York).

Pollock, J.L. (1987). Defeasible reasoning. Cognitive Science, Vol. 11, pp. 481-518.

Pollock, J.L. (1995). Cognitive Carpentry: A Blueprint for How to Build a Person. The MIT Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts).

Prakken, H. (1993). Logical tools for modelling legal argument. Doctoral thesis, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam.

Prakken, H. (1997). Logical Tools for Modelling Legal Argument. A Study of Defeasible Reasoning in Law. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

Verheij, B. (1996). Rules, Reasons, Arguments. Formal studies of argumentation and defeat. Dissertation Universiteit Maastricht.

A summary and table of contents are available on the World-Wide Web at http://www.metajur.unimaas.nl/~bart/proefschrift/.

Verheij, B., Hage, J.C., and Lodder, A.R. (1997). Logical tools for legal argument: a practical assessment in the domain of tort. The Sixth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law. Proceedings of the Conference, pp. 243-249. ACM, New York (New York). An abstract is available on the World-Wide Web at http://www.metajur.unimaas.nl/~bart/papers/icail97.htm.

Verheij, B., and Lodder, A.R. (1998). Computer-mediated legal argument: the verbal vs. the visual approach. Proceedings of the 2nd French-American Conference on AI and Law – June 11-12. Nice, France.

Vreeswijk, G.A.W. (1993). Studies in defeasible argumentation. Doctoral thesis, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam.

Vreeswijk, G.A.W. (1997). Abstract argumentation systems. Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 90, pp. 225-279.