ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Simplement, As A Metalinguistic Operator

The use of simplement, I will be dealing with is often viewed as a weaker version of the adversative marker mais (known as ‘mais-pa’). Simplement, however, will not be appropriate in all the environments where mais-pa is to be found; furthermore, it affects cohesion in different ways, as it calls for different types of continuation, gives rise to a different situation schema and context construction, and lends itself to strategic uses of its own. In this paper I will attempt to clarify those various aspects, which, following Anscombre and Ducrot, I will construe in procedural terms, or in terms of semantic constraints on interpretation.

The use of simplement, I will be dealing with is often viewed as a weaker version of the adversative marker mais (known as ‘mais-pa’). Simplement, however, will not be appropriate in all the environments where mais-pa is to be found; furthermore, it affects cohesion in different ways, as it calls for different types of continuation, gives rise to a different situation schema and context construction, and lends itself to strategic uses of its own. In this paper I will attempt to clarify those various aspects, which, following Anscombre and Ducrot, I will construe in procedural terms, or in terms of semantic constraints on interpretation.

1. Introduction

The use of simplement (henceforth SPT) I am concerned with is one that occurs in examples such as:

(1)

A: Pourquoi est-ce tu ne manges pas ta soupe? Elle est froide?

B: Ce n’est pas qu’elle soit froide, simplement je n’ai pas faim.

A: Why aren’t you eating your soup? Is it cold?

B: It’s not that it’s cold, it’s just that I am not hungry.

(2)

A: Pourquoi est-ce que tu ne veux pas voir Marie?

B: Ce n’est pas que je ne veuille pas la voir, simplement je suis fatigué.

A: Why don’t you want to see Marie?

B: It’s not that I don’t want to see her. It’s just that I am tired.

(3)

A: Ils ne sortent jamais. Est-ce parce qu’ils ont trois enfants?

B: Ce n’est pas qu’ils aient trois enfants. Simplement ils préfèrent travailler le soir.

A: They never go out. Is that because they have three children?

B: It’s not that they have three children. It’s just that they prefer working in the evening.

(4)

A: Pourquoi est-il si triste?

B: Ce n’est pas qu’il ne mange plus de caviar. Simplement ses investissements sont tombés en chute libre.

A: Why does he look so sad?

B: It’s not that he no longer eats caviar. It’s just that his investments have taken a nose dive.

Although my main concern will be with the ce n’est pas que P SPT Q construction, I will also be referring to the following:

(5)

A: Vous êtes pour ou contre cette grève?

B: On les soutient à 100%, simplement cela commence à compliquer la vie de tous les jours.

A: Are you for or against this strike?

B: We are a 100% behind them. It’s just that it is beginning to make everyday life difficult.

(6)

A: Vous avez été voir ce film?

B: Il est tout ce qu’il y a de plus inintéressant. Simplement les enfants ont insisté pour le voir.

A: You went to see that film?

B: It is totally uninteresting. It’s just that the children insisted on going.

(7) Le combat est loin d’être achevé. Simplement il n’a plus le visge d’une action collective.

The struggle is far from over. It’s just that it no longer involves collective action.

Leaving these aside, for the time being, let us turn to the ce n’est pas P SPT Q construction.

As a first approximation of what the speaker S does in saying ‘Ce n’est pas que P SPT Q’, one might want to interpret ‘Ce n’est pas que P’ as a rejection of a real or possible proposal that C1 is the cause of some prior event E; ‘simplement Q’ could then be understood as a counter proposal, that C2 is the actual cause, one which is ‘simpler’ than C1 in some respect.

From this outline two points emerge which require further development. One is the nature and function of the negation involved, the other, the meaning of SPT, which, following Anscombre and Ducrot, I will construe in procedural terms, or in terms of reading instructions.

2. Nature and function of Neg P

From the gloss I have just given one will have gathered that I am leaning towards a metalinguistic reading of the negation, as opposed to a descriptive one. For a quick reminder of what the distinction involves, let’s turn to Horn (1989: 363). According to Horn, ‘…metalinguistic negation focuses on the assertability of an utterance’; by contrast, descriptive negation focuses on the truth or falsity of a proposition. Metalinguistic negation (to quote Horn again) is a ‘…device for objecting to a previous utterance on any grounds whatever, including the conventional implicata it potentially induces, its morphology, its style or register, or its phonological realization’. For examples of metalinguistic negation, consider (8) and (9), borrowed from Anscombre and Ducrot (1977: 26) and Horn (op.cit.: 404), respectively:

(8)

A: Est-ce que Pierre est français?

B: Non, il n’est pas français mais belge.

A: Is Pierre french?

B: No, he isn’t french but belgian.

(9)

We don’t have three children but four.

Metalinguistic negation thus constitutes a comment on a (presumed) comment on facts, which may, but do not necessarily, correspond to the state of affairs described in the propositional content. Descriptive negation, by contrast, will be a comment on the state of affairs described in the propositional content.

Horn (op.cit.: 393-412) proposes three diagnostics for metalinguistic negation. First, metalinguistic negation cannot incorporate prefixally. Thus one can deny the appropriateness of using the predicate ‘possible’ by saying (10), but not (11):

(10)

It’s not possible to see him – it is necessary.

(11)

*It’s impossible to see him – it is necessary.

Similarly, in French one can have (12), but not (13):

(12)

Ce n’est pas possible de le voir – c’est nécessaire.

(13)

*C’est impossible de le voir – c’est nécessaire.

Note also that (14) cannot be taken to express a metalinguistic negation:

(14)

*C’est peu possible de le voir – c’est nécessaire.

* It’s little possible to see him – it’s necessary.

The second diagnostic is based on the fact that metalinguistic negation, unlike descriptive negation, does not trigger negative polarity items. Thus, alongside (15), one will have (17):

(15)

Il n’a rien à me dire.

He has nothing to tell me.

(17)

Il n’a pas quelque chose à me dire, il a beaucoup de choses à me dire.

He does not have something to tell me, he has a lot to tell me.

Where (17) is a metalinguistic negation followed by a rectification of:

(16)

Il a quelque chose à vous dire.

He has something to tell you.

The third diagnostic relies on the correlation that exists between metalinguistic negation and contrastive mais (henceforth mais-sn) on one hand, descriptive negation and concessive mais (henceforth mais-pa) on the other (in Horn this point was made about but ). Thus in (18), a clear case of rectification, the mais is a mais-sn:

(18)

Ce n’est pas beau mais-sn divin.

It’s not beautiful but-sn divine.

By contrast in (19) where S denies that the object under discussion is divine, the mais is a mais-pa:

(19)

Ce n’est pas divin, mais-pa c’est tout à fait charmant.

Neg – P – Q

It’s not divine, but-pa it’s quite charming.

In argumentative terms Anscombre and Ducrot (op.cit.) describe P and Q as arguments for the same conclusion r, with P being argumentatively superior to Q.

My claim that SPT is preceded by a metalinguistic negation does not fare too well by these diagnostics. Thus, X can include a morphologically incorporated negation, as in (6):

(6)

Il est tout ce qu’il y a de plus inintéressant, simplement les enfants ont insisté pour le voir.

It is totally uninteresting; it’s just that the children insisted on gong.

Furthermore, an appropriate substitute for SPT would be mais-pa, rather than mais-sn, which correlates with the failure of Neg P SPT Q constructions to exhibit distributional properties characteristic of mais-sn: according to Anscombre and Ducrot (op.cit.), mais-sn appears only after a syntactic negation and in reduced clauses, and collocates with au contraire, which can also replace it. To these we may add the possibility of a paraphrase with non or non…pas, suggested by Plantin (1978). This contrast between mais-sn and SPT is shown in the following paradigms:

(20)

Ce n’est pas intéressant mais-sn révélateur.

It’s not interesting but-sn revealing.

(21)

*C’est inintéressant mais-sn révélateur.

*It’s uninteresting but-sn revealing.

(22)

Ce n’est pas intéressant mais-sn au contraire révélateur.

It’s not interesting but-sn, on the contrary, revealing.

(23)

Ce n’est pas intéressant, au contraire, c’est révélateur.

It’s not interesting, on the contrary, it’s revealing.

(24)

C’est non pas intéressant mais-sn révélateur.

It’s not interesting but-sn revealing.

(25)

Ce n’est pas intéressant, simplement c’est révélateur.

It’s not interesting, it’s just that it is revealing.

(26)

C’est inintéressant, simplement c’est révélateur.

It’s not uninteresting, it’s just that it is revealing.

(27)

*Ce n’est pas intéressant, simplement au contraire c’est révélateur

*It’s not interesting, on the contrary it’s just that it is revealing.

(28)

?Ce n’est pas intéressant, au contraire c’est révélateur.

?It’s not interesting, on the contrary, it is revealing.

(29)

*C’est non pas intéressant, simplement c’est révélateur.

It’s not interesting, it’s just that it is revealing.

Diagnostic two – the failure of metalinguistic negation to trigger negative polarity items – is the only one that yields positive results, as shown by:

(30)

Ce n’est pas qu’il ait quelque chose à me dire, simplement il a besoin d’une voiture pour demain.

It’s not that he has something to tell me; it’s just that he needs a car for tomorrow.

So, if I wish to maintain that SPT requires a preceding metalinguistic negation, I need to be able to explain why one should disregard the results of diagnostics one and three. Diagnostic one, which, one will recall, relies on the inability of lexical negation to function metalinguistically, is best construed as a means to seek an answer to the following question: ‘Given two explicit negations, one syntactic, one lexical, which of the two can function metalinguistically?’. The underlying assumption being that a negation cannot have this function unless it is inherently metalinguistic. The question one needs to ask in the case of SPT concerns its function only: ‘Given an X SPT Y construction, does the utterance of X always constitute a metalinguistic rejection of some aspect of a prior utterance (either real or presumed)?’ In other words, metalinguistic negation, as envisaged under a functional aspect (i.e., as a process), need not be effected uniquely via a syntactic negation. In addition to such a negation, X may be instantiated by a lexical one, or even no negative element at all. The metalinguistic value in all cases would be due to or reinforced by an instruction conveyed by SPT.

Now, what about diagnostic three? The problem with diagnostic three is that it takes rectification (or correction of A’s utterance at the utterance production level) to be a constant feature of metalinguistic negation. If the function of metalinguistic negation is to object to a prior utterance on any grounds whatever, then, unless for some reason, corrections have to be confined to the ‘materiality’ of the prior utterance, it is unclear why one has to have a rectification as a compulsory feature of metalinguistic negation. In other words, with Neg P SPT Q constructions, Neg P can still be a metalinguistic negation of P if the utterance of ‘SPT Q’ does not constitute a rectification in the canonical sense. Under diagnostic three, there is one important correlate of

metalinguistic negation pointed out by Anscombre and Ducrot (op.cit), which I did not list, and that is the possibility of replacing ‘mais-sn Q’ by paratactic syntax with no overt conjunction. Although SPT cannot be replaced by mais-sn, since the correction does not occur at the same level, ‘SPT Q’ can be replaced by a paratactic clause. Thus, alongside (30), one can have:

(31) Ce n’est pas qu’il ait quelque chose à me dire: il a besoin d’une voiture pour demain.

It’s not that he has something to tell me: he needs a car for tomorrow.

The acceptability of (31) as a paraphrase for (30) I take to be an indication that SPT can be preceded by metalinguistic negation.

Having explained why existing diagnostics do not always work for SPT, I propose to turn to those that do work. Once the notion of rectification has been put into perspective, what remains of ‘core features’ of metalinguistic negation are: a) the fact that it constitutes an objection to a prior utterance; and b) that the truth value of P plays no role in its rejection. The first point has already been taken care of by diagnostic two, so let’s turn to the second. Consider again (1) to (4) (repeated in (32) to (35)). The claim that the truth value of P plays no role in its rejection is supported by the fact that Neg P is compatible with a continuation which unambiguously forces this reading on the string:

(32)

Ce n’est pas qu’elle soit froide – ou pas froide d’ailleurs/ elle est même gelée/quoiqu’elle le soit, effectivement – simplement je n’ai pas faim.

It’s not that it is cold – or not cold, for that matter/ it is even frozen/although it is cold – it’s just that I am not hungry.

(33)

Ce n’est pas que je ne veuille pas la voir – ou que je le veuille d’ailleurs/ même si en fait je veux la voir – simplement suis fatigué.

It’s not that I don’t want to see her – or want to, for that matter/even if in actual fact, I do want to see her – it’s just that I am tired.

(34)

Ce n’est pas qu’ils aient trois enfants – ou même quatre/d’ailleurs ils n’en ont pas – simplement ils préfèrent travailler le soir.

It’s not that they have three children – or even four/ as a matter of fact, they don’t have any – it’s just that they prefer to work in the evening.

(35)

Ce n’est pas qu’il ne mange plus de caviar – ou qu’il en mange encore, d’ailleurs / en fait il n’en a jamais mangé/ quoique cela demande à être vérifié – simplement ses investissements sont tombés en chute libre.

It’s not that he no longer eats caviar – or that he still eats it, for that matter/ as a matter of fact he has never eaten it/ although that remains to be seen – it’s just that his investments have taken a nose dive.

Matters, however, are less straightforward with other realizations of Neg P. Nonetheless, there is a type of continuation that appears to work for all cases involved, and that is ‘la question n’est pas là’ (‘that’s not the point’). Thus this continuation would be compatible with (5) to (7) (repeated in (36) to (38)), as well as (1) to (4):

(36)

On les soutient à 100% – là n’est pas la question – simplement cela commence compliquer la vie de tous les jours.

We are 100% behind them – that’s not the point – it’s just that it is beginning to make everyday life difficult.

(37)

Il est tout ce qu’il y a de plus inintéressant – là n’est pas la question – simplement les enfants ont insisté pour le voir.

It is totally uninteresting – that’s not the point – it’s just that the children insisted on going.

(38)

Le combat est loin d’être achevé – là n’est pas la question – simplement il n’a plus le visage d’une action collective.

The struggle is far from over – that’s not the point – it’s just that it no longer involves collective action.

3. Neg P SPT Q

On the basis of what we have just seen, it would appear that the grounds on which P is being rejected have nothing to do its truth value, but rather with the fact that it belongs to a category of causes which is deemed irrelevant. If we were now to assume that Q is introduced by SPT as an appropriate substitute for P, then the question of the relationship between P and Q will have to be posed. But first we need to specify what a situation schema for Neg P SPT Q would include.

Consider (2) again. The prior event E could be B’s lack of enthusiam at the prospect of inviting Marie. A’s question presupposes P (=/tu ne veux pas voir Marie/) which expresses a cause C1 for E. In saying ‘ce n’est pas que je ne veuille pas la voir’, B is objecting to P on grounds that whether or not he wants to see her is beside the point. In proceeding with ‘simplement je suis fatigué’, B purports to provide the actual cause C2 for his lack of enthusiasm, a cause which is presented as ‘simpler, in the sense of ‘socially more acceptable’. (With the right assumptions in place, A’s question could be construed as an indirect accusation, and B’s ‘SPT Q’, as an attempt to show that the actual cause for E is less incriminating than what A had supposed. In any case, the mere fact of presenting Q as simpler creates an implicature that A should have known it all along, hence the value of reproach which could be associated with the use of SPT).

A situation schema for this type of construction would then have to include a prior event E, a presumed or actual proposal P of A’s, that C1 is the cause of E, and a rejection of P on the part of S, to be followed by a proposal Q that C2 is the cause of E, with C2 being presented as ‘simpler’ than C1. In addition, it would have to cater for the fact that ‘Ce n’est pas que P’ gives rise to a paradigm, and ‘SPT Q’ to a scale. The paradigm arises in the sense that one cannot fully understand the negation, unless one can sort out what it cannot be taken as not meaning, no matter how incidental this might be. As for the scale, it is presupposed by SPT, which presents the category of causes that includes C2 as outranking the one that includes C1, in terms of appropriateness and simplicity. Both appropriateness and simplicity are relational properties of causes, with the former highlighting their relation to E, and the latter, their relation to the speech participants. Simplicity, as envisaged here, should be taken to mean ‘obvious’, to cater for the interrelational aspect of SPT: to say ‘SPT Q’ is to presuppose, to varying degrees, that Q should be obvious to A.

In (2), the paradigm triggered by ‘ce n’est pas que P’ would include values such as:

– J’ai toujours plaisir à la voir.

– I always enjoy seeing her.

– (quoique) je ne suis/sois pas sûr de vouloir la voir.

– (although) I am not sure I want to see her.

– Cela m’est indifférent de la voir ou non.

– I don’t mind one way or another.

Each of which functions as an indirect denial that P is being rejected on grounds of its truth value, and can provide an appropriate, albeit parenthetical, continuation to ‘ce n’est pas que P’. As for the scale, it would exhibit, at one end, the category of causes that includes P and ~P ( /je veux la voir/, /je ne veux pas la voir/), and, at the other, the one to which Q (/je suis fatigué/) belongs.

Paradigm and scale together constitute a two step correction process, with the paradigm providing a rejection of a descriptive interpretation of Neg P, and the scale providing a value for its metalinguistic interpretation.

4. Relationship between P and Q

The question of the relationship between P and Q (or rather the causes they express) naturally arises because of the contrast presented by examples such as (39) and (40), both of which are S’s responses to A’s question:

A:

John semble avoir beaucoup d’argent.

John seems to have a lot of money.

(39)

S: ? Ce n’est pas qu’il travaille pour la CIA, simplement il fait partie de MI5.

? It’s not that he works for the CIA, it’s just that he is a member of MI5.

(40)

Ce n’est pas qu’il travaille pour la CIA, simplement sa famille est très aisée.

It’s not that he works for the CIA, it’s just that he comes from a well-off background.

This contrast would appear to indicate that there is a constraint at work, one which requires that C1 and C2 should belong to the same category of causes. This finds corroboration in the oddity of (41), which involves gradual predicates:

(41)

*Ce n’est pas que ses mains soient gelées, simplement elles sont froides.

*It’s not that his hands are frozen, it’s just that they are cold.

To be acceptable (41) would require a context where ‘froid’ could be construed as part of an unrelated scale, and a member of a category that could be opposed to that of ‘gelé’ and ‘pas gelé’. In other words, SPT in this case would have the effect of ‘dislocating’ a natural scale. Note, however, that the level of acceptability improves markedly if C1 and C2, though thematically part of the same category, belong on opposite scales, e.g. that of heat and that of cold, as in:

(42)

Ce n’est pas que ce soit froid, simplement c’est tiède.

It’s not that it is cold, it’s just that it is lukewarm.

Furthermore, if one remains within the same scale, a dislocation would appear to be easier if C1 and C2 are not adjacent. Thus, although both (43) and (44) involve the epistemic scale, (43) seems to be more acceptable than (44):

(43)

Ce n’est pas que ce soit certain, simplement c’est possible.

It’s not that it is certain, it’s just that it is possible.

(44)

*? Ce n’est pas que ce soit certain, simplement c’est probable.

*? It’s not that it is certain, it’s just that it is probable.

As for non gradual cases, (45) gives some idea of how close C1 and C2 can be and still be appropriately used with SPT:

(45)

Ce n’est pas que je ne veuille pas inviter Marie, simplement j’aimerais inviter quelqu’un d’autre.

It’s not that I don’t want to invite Marie; it’s just that I would like to invite someone else.

In a context where there can only be one guest at a time, this gives an impression of backtracking on the part of S. However, closer scrutiny reveals that, although inviting someone else also necessarily excludes inviting Marie, the fact of the matter is not whether Marie should be invited, but whether there is someone else S wants to invite. That inviting someone else should exclude inviting Marie is incidental. In other words, what separates C1 and C2 (or rather their respective categories) can simply be a matter of focus. The fact that a sheer difference in focus qualifies as a relevant distinction appears to be behind a frequent strategic use of SPT, one which enables S to maintain contradictory stances by introducing ‘hair splitting’ differences. Consider (5) again, where S, while objecting to the idea that he is against the strike appears to be preparing the grounds for withdrawn his support. A further example is (26), where S may be perceived as wanting her cake and eating it too:

(46)

Ce n’est pas que le combat pour la parité soit achevé, simplement maintenant c’est chacune pour soi.

It’s not that the struggle for equality is over; it’s just that now it is each woman for herself.

In this case the difference between C1 and C2 is one between a process and how it is carried out.

One last point needs to be raised about the situation schema. So far my main concern has been with Xs that include an overt negative element. What about cases like (5), where X is an affirmative clause, and the value for what S cannot be taken as not meaning (¬P) is clearly stated? Surely (5) can hardly be said to give rise to any paradigm of possible values for ¬P ? My proposal is to view ‘on les soutient à 100%’ as an element of the paradigm itself, but one whose selection and materialization has rendered the rest of the paradigm less accessible. The underlying situation schema for (5) would not start with a value for ¬ P, but a rejection of P (which might have been realized as ‘ce n’est pas qu’on ne les soutienne pas’), to be followed by a paradigm of possible values for ¬P, from which ‘on les soutient à 100% would be chosen.

As my final point, I propose to turn to a possible objection: if SPT requires a metalinguistic negation, how come the same environments can accept mais-pa? This objection is based on the assumption that the elements to be contrasted are the same in both cases, which is debatable. Consider:

(47)

Ce n’est pas qu’on ne les soutienne pas, simplement cela commence à compliquer la vie de tous les jours.

(48)

Ce n’est pas qu’on ne les soutienne pas, mais-pa cela commence à compliquer la vie de tous les jours.

The appropriate gloss for (48) would be: It is not that we don’t support them, but from the fact that we are rejecting the idea that we might not support them one is not to infer r (i.e. that we will continue to support them indefinitely), the reason being Q. An alternative way of analyzing (48) that shows that mais-pa is not directly concerned with the metalinguistic negation involves the use of the situation schema. Consider:

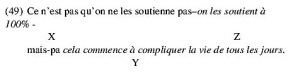

(49) Ce n’est pas qu’on ne les soutienne pas–on les soutient à 100% – (see: illustration)

In (49) where the value to be attributed to ¬P is made explicit in Z (a value, incidentally, which is to be associated with a descriptive interpretation of the negation), it is the latter that makes a more convincing candidate for what precedes mais-pa. To wrap up this argument, one might say that the assumption behind this objection is that we are dealing with the Neg P mais-pa Q construction, when in fact the relevant one is simply P mais-pa Q. The surface structure may contain a metalinguistic negation, but the latter is not on the same level as mais-pa.

5. Conclusion

While much about SPT has been left untouched, the following points emerge which have a direct bearing on the study of argumentation. As a metalinguistic operator construed in procedural terms (as opposed to distributional ones), SPT brings further support to the idea, inherent in Anscombre and Ducrot’s Argumentation Theory, that language constitutes a possible source for patterns of reasoning and inferential routes. Furthermore, the fact that it gives rise to a paradigm and a scale provides some insight into how evaluation contexts are constructed. From a strategic standpoint, while the use of SPT suffices to constrain A’s inferential routes and delay the construction of her own context of evaluation, thinking in procedural terms caters for a further form of manipulation: the fact that a situation schema is being projected on available contents (as opposed to the actual context and cotext being assessed for their level of appropriateness) means that C2s that would not normally qualify as simpler or as belonging to a distinct category from C1s can, nevertheless, be presented as meeting those criteria – albeit to varying degrees.

REFERENCES

Anscombre, J.C., Ducrot, O. (1977). Deux mais en Français? Lingua 43, 23-40.

Horn, L.R. (1985). Metalinguistic negation and pragmatic ambiguity. Language 61(1), 121-174.

Horn, L.R. (1989). A Natural History of Negation. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Nyan, T. (1998). Metalinguistic Operators, with reference to French. Berne: Peter Lang.

Nyan, T. (1998).Vers un schéma de la différence.To appear in Journal of French Language Studies.

Plantin,C. (1978) Deux mais. Semantikos 2 (2-3),89-93.