1. Introduction

1. Introduction

What are ‘figures of speech’ (henceforth: ‘FSP’)? How can they be classified? And how can we evaluate their use in keeping with the standards for rational discussions? These three general questions will be discussed in this paper.

As far as the first question is concerned, I wish to review a few attempts to define and characterize FSP. More particularly, I would like to criticize views which mainly characterize FSP as ornamental devices or as a means to make everyday language more persuasive. This way, the existence of a ‘neutral’, non-figurative language, which supposedly presents the bare facts, is taken for granted. These views were already formulated in ancient rhetoric, but still find their successors in recent theories of style which characterize FSP as a deviation from a kind of ‘zero-variety’ of language.

I would like to defend a radically different point of view, which has been developed over the last few decades by linguists, philosophers and psychologists like for example Ivor Armstrong Richards, Eugenio Coseriu, Max Black, Paul Ricoeur, Umberto Eco, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson. They suggest that FSP like metaphor, metonymy, hyperbole and irony 1) are an integral part of our ability to use language and 2) play an eminent role in our cognitive system. This role cannot be reduced to ornamental and persuasive functions, because according to this view, FSP partake in the definition of language as a creative communicative activity. Therefore, they cannot be seen as secondary phenomena which always have to be derived from a zero-variety of language via certain linguistic operations, contextual clues or conversational implicatures.

The second question will be approached by taking a critical look at various traditional and modern typologies of FSP. Several recent attempts have tried to overcome the traditional division of FSP into tropes, figures of diction, and figures of thought. There is no doubt that these new typologies provide important insights and improvements as far as modern linguistic standards of classification are concerned. However, there remain many empirical and theoretical problems which I would like to discuss briefly, using examples from various types of texts and from different languages (all examples from languages other than English will be translated; unless indicated otherwise, these translations are mine).

The third question concerns the problem of distinguishing between rational and fallacious uses of particular FSP. Most of the traditional types of fallacies are connected with problems of formulation, including those fallacies which Aristotle classified as ‘extra-linguistic’ (cf. Aristotle, soph.el. 165b). Therefore, it very often depends on how a particular line of reasoning is verbally presented with the help of FSP whether it can be considered as rational or irrational. Of course, any attempt to distinguish between rational and fallacious uses of FSP presupposes a definition of rationality. Therefore, I will first briefly deal with some problems of defining rationality and then proceed with an analysis of some examples, again taken from authentic texts in different languages.

One final remark before I begin: given the fact that there is an overwhelming amount of literature about FSP, it has become virtually impossible to deal with all the major contributions, let alone consider most or everything that has been written about FSP. So let me put it this way: I have tried to take into account as much as possible without drowning…

2. On Defining FSP

In ancient rhetoric, FSP[i] were characterized as a kind of ornament which is added to plain speech, which is merely clear and plausible. Thus FSP are conceived of as a kind of ‘clothing’, an ‘ornament’ which makes ordinary speech more attractive and efficient (cf. Quintilian inst.orat. 8.3.61: ‘ornatum est, quod perspicuo ac probabili plus est’). Further metaphorical characterizations of FSP in ancient and medieval rhetoric are ‘flores’ (flowers), ‘lumina’ (highlights) and ‘colores’ (colours) (cf. Cicero or. 3.19, 3.96, 3.201; Knape 1996: 303). More specifically, tropes are characterized by Quintilian as a kind of semantic change, where the proper meaning of a word or phrase is replaced by a new meaning which enhances the quality of speech (cf. Quintilian inst.orat. 8.6.1: ‘tropos est verbi vel sermonis a propria significatione in aliam cum virtute mutatio’). FSP in the narrow sense are defined as some artistic innovation of speech (cf. Quintilian inst.orat. 9.1.14: ‘figura sit arte aliqua novata forma dicendi’).

This perspective has been taken up and refined by modern linguistic theories of style and poetic language. Within these frameworks, FSP are conceived as deviations from everyday language. In his classical article on poetics and linguistics, Jakobson (1960: 356) has tried to formulate a general semiotic framework for a deviational perspective where ‘The set (Einstellung) toward the MESSAGE as such, the focus on the message for its own sake, is the POETIC function of the language’. This specific focus on the message for its own sake is realized by ‘the principle of equivalence’ (ibid. 358): ‘The poetic function projects the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection into the axis of combination’: semantically equivalent or similar linguistic units are selected from a paradigm in a way that phonetically equivalent or similar units are established on the syntagmatic level. For example, the adjective ‘horrible’ is selected from a lexical paradigm also containing the synonyms ‘disgusting’, ‘frightful’, ‘terrible’ etc. to produce the alliterating noun phrase ‘horrible Harry’.

Following the basic semiotic principles outlined by Jakobson, linguists and literary criticists have developed detailed and sophisticated deviational approaches, for example G. Leech (1966), T. Todorov (1967), the Belgian ‘groupe m’ (Dubois et al. 1974) and H.F. Plett (1975). I will return to these approaches (cf. section 3). Despite its intuitive appeal, deviation theory has had to face severe criticism (e.g. by Coseriu 1971, 1994: 159ff.; Spillner 1974: 39f.; Ricoeur 1975: 1173ff.; Knape 1996: 295ff.). I consider this criticism as basically justified. It is true that modern deviation theory has developed much more sophisticated standards of explicitness and consistency than ancient rhetoric. But still, the following weak points remain:

1. It is very hard to isolate a zero-variety of language which could serve as the basis from which figurative language is derived via the principle of equivalence and more specific linguistic operations. That a zero-variety is difficult to establish is conceded even by deviation theorists (cf. Todorov 1967: 97ff.; Dubois et al. 1974: 59). FSP occur – and sometimes are even extremely frequent – in many instances of everday language: in conversations, political speeches, advertising texts, fairy tales, slogans, idioms and proverbs (many examples are given by Klöpfer 1975). Moreover, Gibbs (1994: 123f.) refers to empirical studies which provide frequency counts of metaphors within different types of text. These studies show that speakers use 1.80 creative and 4.08 dead metaphors per minute of discourse. Finally, recent publications on metaphor stress the crucial role of metaphor even in languages for specific purposes (for example, in scientific language: cf. Kittay 1987: 9; Pielenz 1993: 76ff., Gibbs 1994: 169ff.).

2. Quite often FSP are not even replaceable by a ‘proper’ expression because such a proper expression simply does not exist and we have to rely on figurative language (cf. Weydt 1987, Coseriu 1994: 163). This was already acknowledged by ancient deviation theorists like Quintilian (cf. inst.orat. 8.6.6.: ‘necessitate nos ‘durum hominem’ aut ‘asperum’: non enim proprium erat quod daremus his adfectibus nomen’; cf. also Aristotle poet. 1457b 25-26).

This is not to deny the fact that in many cases we can distinguish proper and figurative language. As far as metaphor is concerned, Kittay correctly remarks: ‘One can and ought to make the literal/metaphorical distinction while agreeing that metaphors are central to our understanding and acting in the world’. Even ‘dead’ or ‘frozen’ metaphors, which have almost become ‘literal’ expressions, can be recognized as such: ‘One need only make the distinction relative to a given synchronic moment in a given language community’ (Kittay 1987: 22; cf. also Pielenz 1993: 67, n. 40). But quite often, they can no longer be replaced by ‘proper’ expressions and have become basic elements of our conceptual system.

Moreover, the psycholinguistic evidence referred to by Gibbs (1994: 80ff., 399ff.) provides reasons to assume that FSP are processed as naturally and quickly as ‘proper’ expressions. Thus, this evidence challenges the view that figurative speech requires special or additional mental processes for it to be understood. It also shows that the ability to use FSP is acquired early by children.

3. Deviation theory could imply the assimilation of FSP with mistakes, which are indeed ‘deviations’. However, unlike mistakes, FSP are the result of intentional operations. Furthermore, in the normal case the results of these operations are texts which have been adapted well for their specific purpose. It would be most implausible to assume that we first choose ‘proper’, but less adequate expressions from a zero-variety, then recognize that they are not adequate and then substitute them with figurative expressions. It is more plausible to assume that we directly select the most suitable verbal tool from the available paradigms in our language. Therefore, deviation theory should be replaced by a selection theory of style (cf. e.g. Marouzeau 1935: Xff., Spillner 1974: 64, Van Dijk 1980: 97) or, on a more general level, by a pragmatic theory which models language use as a process of selective adaptation to context (cf. Verschueren 1998).

4. FSP are phenomena occurring at the textual level of language. Traditionally prevailing views of sentence grammarians (which reappear in modern rhetorical studies like for example those of Dubois et al. 1974: 260f.) claimed that the text level does not belong to the language system proper. However, textlinguists have amply demonstrated in the past few decades (cf. e.g. Van Dijk 1980, Coseriu 1994) that the text level, too, is at least partially organized according to language-specific rules. FSP are realized by verbal strategies which form an essential part of our textual and/or communicative competence. Therefore, they are not merely secondary phenomena of ‘parole’ or linguistic performance, but partake in a definition of language as a creative, communicative activity (cf. Coseriu 1956:22: ‘la creación, la invención, es inherente al lenguaje por definición’ and Coseriu 1971, Ricoeur 1975: 87ff.; Kienpointner 1997).

From these arguments we can derive the following conclusion: FSP are not merely ornamental or aesthetic devices. Many FSP are linguistically and cognitively basic. Therefore, they inevitably shape our cognition and culture-specific views or reality. This has been especially stressed in recent studies on metaphor: ‘Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature’ (Lakoff/Johnson 1980: 3)[ii]. In this respect, also conventionalized tokens of FSP are particularly important because unlike newly created instances of FSP they have ceased to attract our attention and have thus become unnoticed cognitive background phenomena. At this stage of the discussion, deviation theorists would perhaps accept some of the criticism mentioned above. But they could still argue that a restricted version of deviation theory is correct under the following conditions:

1. Its claims are restricted to poetic literature in the narrow sense of the word.

2. The difference between everyday language and poetic language is no longer seen as a qualitative deviation but as a quantitative deviation: truely poetic texts like poems usually contain more FSP than, say, editorials or parlamentary speeches.

3. It is restricted to creative FSP, which have not (yet) been conventionalized.

For example, creative metaphors – unlike dead metaphors – clearly seem to deviate from everyday language. This is a plausible claim. After all, a radical view like the one taken by Nietzsche, who states that everyday speech is basically equivalent to figurative speech[iii], cannot explain the undeniable difference between creative and conventionalized FSP.

These arguments are relevant and important. Still, I believe that they can be refuted. It is true that there is a clear statistical difference between the frequency of FSP in poetic texts and everyday language. However, this difference does not justify considering poetic language as a deviation from everyday language. As FSP partake in the definition of language as a creative activity and FSP are present in all kinds of language varieties, the difference of frequency simply does not justify seeing poetic language as a deviation from other varieties of language. Rather, everyday language or scientific language could be seen as ‘deviations’ from or ‘reductions’ of poetic language. Only the latter fully exhausts the creative potential of language by using all available verbal strategies. Poetic language (or figurative language in general) can thus be seen as language in its fullest sense, as the realization of all or most creative possibilities offered by language (cf. Coseriu 1971: 184). In this respect, conventionalized FSP are not substantially different from creative FSP. In both cases, figurative patterns are used to produce texts for some communicative purpose, only that in the case of creative FSP, new ways of formulating meaningful texts are recognized and implemented by gifted individuals (who, however, need not be poets or trained speakers to be successful!). Conventionalized FSP are verbal strategies used to repeat these original creations, to ‘re-create’ tokens of utterances according to stylistic patterns which are already accepted and widely used in a speech community. But this is only a difference of degree, because new realizations of FSP can gradually spread to the whole speech community and sooner or later also become conventionalized. It is in this context that Spitzer (1961: 517f.) rightly characterized syntax and grammar as ‘frozen stylistics’. In the light of the preceding discussion, I suggest the following definition of FSP (cf. also Ricoeur 1975: 10):

FSP are the output of discourse strategies which we use to select units from linguistic paradigms of different levels (phonetics/ phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics) to create texts which are adequate as far as their communicative purpose in some context is concerned.

From the perspective of the audience, the same process can be conceived of as an infinite sequence of the interpretations of texts. This time, the FSP in a text are used as interpretive clues or hints for the attentive hearer/reader. Again, most of the time we repeat or ‘re-create’ standard interpretations of these texts. But the list of standard interpretations can be creatively extended by detecting new FSP in the text or by detecting non-traditional interpretations of well-known FSP. In this way, non-standard interpretations can be found. The use of FSP can thus be defined as an open-ended, creative communicative activity of both speaker and hearer (cf. Coseriu 1958, 1994).

3. Towards a Classification of FSP

From antiquity onwards, FSP have been classified according to the trichotomy of

1. tropes (e.g. metaphor, metonymy, hyperbole, irony),

2. figures of diction (e.g. anaphor, parallelism, climax, ellipsis)

and

3. figures of thought (e.g. rhetorical question, exclamation, persuasive definition, personification).

This typology was often taken up in (slightly) modified versions in medieval and early modern times and survives even into our times: for example, in spite of some modifications the classification of FSP in the neo-classical handbook by Lausberg (1960) still resembles the ancient typology (e.g. by taking up the distinction between tropes and figures) and the treatment in Ueding/Steinbrink (1986: 264ff.) is even closer to the ancient typology. Already Quintilian, however, conceded that there is no consensus as to the number of tropes and the delimitation of certain other FSP (inst.orat. 8.6.1). Moreover, the traditional typology offers no clear demarkation of linguistic levels, apart from the problematic dichotomic distinction of figures of diction and figures of thought (cf. Knape 1996: 310ff.). According to this dichotomy, figures of diction are fundamentally changed if the specific wording of a figure is altered. Figures of thought are said to remain the same even if the formulation is (slightly?) modified[iv]. Furthermore, promising attempts to classify all FSP according to the four basic linguistic operations used to realize them were not carried out consistently[v].

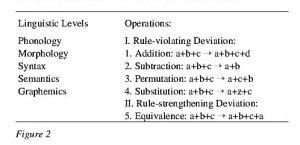

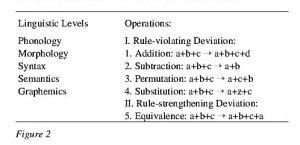

Therefore, it is not surprising that recent typologies (cf. Leech 1966, Todorov 1967, Dubois et.al. 1974, Plett 1975, 1985) try to overcome the deficiencies of the traditional typology. Most of these typologies use two basic principles for the classification of FSP: 1) a distinction of linguistic levels at which the FSP are situated; 2) a distinction of several basic operations which realize particular FSP. I would like to stress that these principles of classification are valuable even if we are not willing to accept the deviational framework behind such typologies.

To illustrate these typologies, I have taken Plett (1975) as an example. Plett starts from a deviational perspective, but refines it considerably, distinguishing between ‘rule-violating’ deviation and ‘rule-strengthening’ deviation (cf. also Todorov 1967: 108). This way he avoids part of the criticism against deviation theory mentioned above (cf. section 2): at least some FSP are rightly classified as operations which enforce rules of everyday language – often extending their frequency of application – rather than violating them. Rule-violating deviation is based on the four elementary operations of addition, subtraction, permutation and substitution, which are executed at all linguistic levels, from the phonemic/morphemic level to text level. Some examples of FSP derived by these four operations are: prosthesis, parenthesis, tautology (addition); syncope, ellipsis, oxymoron (subtraction); metathesis, inversion, hysteronproteron (permutation); substitution of sounds or syllables, exchange of word classes, metaphor, metonymy, irony (substitution).

Rule-strengthening deviation is based on various kinds of repetition, which concern either the position of linguistic elements or their size or their degree of similarity, frequency and distribution. Here are some examples of FSP resulting from rule-strengthening deviation, again taken from various levels (from phonemic/morphemic level to text level): alliteration, assonance, anaphor, parallelism, synonymy, simile, allegory (position); rhyme (size); partial equivalence of vowels /consonants, puns, parison (similarity); the same FSP can be studied as to their frequency and distribution in a text.

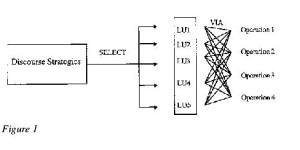

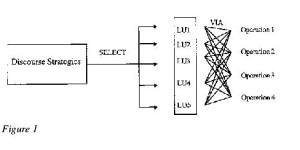

Plett’s elaborate classification could be subsumed under a definition of FSP like the one I have defended in section 1. From the perspective of a selection theory of style, we could see the 4 operations as an implementation of selection strategies, as a means to transform linguistic units of a paradigm into other units of the same paradigm (at the same level) and vice versa. This perspective is summarized in Figure 1:

Abbreviations: LU1-5 = Linguistic units from different paradigms at different linguistic levels (e.g. phonemic, morphemic, syntactic, semantic level): sounds, syllables, words, phrases, clauses, sentences; word meaning…sentence meaning; Operation 1-4: Addition, Subtraction, Permutation, Substitution.

This display shows that, unlike deviation theory, we need not assume that one of these linguistic units (phonemes, morphemes, phrases, clauses, word meanings and sentence meanings) is part of a zero-variety of language and all the others are derived from it. Rather than assuming a unidirectional transformation of linguistic elements which always starts from an unmarked zero-level, the four operations would be better conceived of as multilateral transformations which can operate in all directions, from linguistic unit 1 to unit 2, 3, 4, 5 as well as from unit 2 to unit 1, 3, 4, 5 etc.

I will now turn to the details of Plett’s typology. Plett distinguishes the following linguistic levels: phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics and graphemics[vi]. Plett classifies all FSP according to the respective operations and levels of analysis. The following display shows a summary of Plett’s typology (1975: 148). Note that ‘rule-strengthening’ deviation is a further operation which has to be added to the 4 basic ‘rule-violating’ deviations:

Plett illustrates his typology with examples which are mainly taken from German and English poetic texts. Due to lack of space I must content myself with quoting only a few of Plett’s examples for rule-violating FSP at the semantic level (cf. Plett 1975: 252ff.). However, I have added a few further examples taken from other languages and other types of discourse such as everyday conversation, political speeches and advertisements:

I. Rule-violating Deviation at the semantic level

1. Addition:

Tautology (with the help of synonymic expressions, the same semantic content is predicated twice):

(1)

Hamlet:: There’s ne’er a villain dwelling in all Denmark

But he’s an arrant knave (W. Shakespeare, Hamlet I.5: 123f.; H. Craig: The complete Works of Shakespeare. Chicago: Scott 1951: 911)

(2)

GW: Why would you want to hack in Paoli eight hours a day?

DE: A job’s a job.

(6 March 1985; from the corpus of tautological utterances in Ward/Hirschberg 1991: 512ff.; cf. also colloquial tautologies like Boys will be boys, Business is business etc.)

2. Subtraction

Oxymoron/Paradoxon (antonymic semantic properties are ascribed to the same object simultaneously, within the same noun phrase or sentence):

(3)

Romeo: Why, then, o brawling love! O loving hate!...O heavy lightness!…cold fire, sick health! Still-waking sleep, that is not

what it is!

(W. Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet I.1.182-187; H. Craig: 397)

(4)

Opel Omega. Son silence est la plus belle des symphonies.

(Opel Omega. Its silence is the most beautiful symphony)

(LE FIGARO 491/30.9.89, S. 51)

(5)

Patria… tacita loquitur

(Our native country talks silently) (Cicero, In Catilinam 1.7.18)

(6) Cum tacent, clamant

(While being silent they shout) (Cicero, In Catilinam 1.8.21)

3. Permutation

Hysteronproteron (a clash between temporal succession and linear word order: a chronologically later event 1 is presented earlier in the text and followed by the chonologically earlier event 2 later in the text):

(7)

Ihr Mann ist tot und läßt Sie grüßen.

(Your husband is dead and sends you his regards)

(W. v. Goethe, Faust I. 2916)

4. Substitution

Metaphor (expressions containing semantic features like [+abstract] or [+visual] are combined with other expressions containing semantic features like [+concrete] or [+acoustic]/[+tactile] in the same phrase, clause or sentence):

– [+abstract] -> [+concrete]:

(8)

…hands/ That lift and drop a question on your plate

(T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, 29f.)

(9)

stirps ac semen malorum omnium

(the root and the seed of all evils)(Cicero, In Catilinam 1.12.30)

(10)

He (= Ronald Reagan) took words and sent them out to fight for us

(Peggy Noonan, TIME 151.15 (April 13 1998): 101)

(11)

C’est une Française qui a donné une medaille à la France

(It’s a French woman who has given a medal to France)

(Roxana Maracineanu, L’EXPRESS 2439, 2/4 (1998): 10)

– [+visual] -> [+acoustic]:

(12)

Pyramus: I see a voice

(W. Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream V.1. 194; H. Craig: 203)

– [+visual] -> [+tactile]:

(13)

Von kühnen Felsen rinnen Lichter nieder

(From bold rocks lights are flowing down) (Cl. Brentano, Der Abend)

Apart from its deviation-theoretic background, which can of course be criticized (cf. section 2), Plett’s typology is to be praised for the following reasons:

1. The principles of classification are much more transparent than in traditional classifications.

2. Standards of explicitness and demarkation are thus considerably raised.

3. The cross-classification based on basic operations and linguistic levels is carried out much more consistently than in typologies following the classical tripartite classification.

But still, important points of criticism remain. First, a high degree of intersubjective reliability has apparently been realized only at the phonological, morphological and syntactic levels. Here, different typologies classify in much the same way. This can be seen by a comparison of recent typologies by Plett and the ‘groupe m’ (Dubois et al. 1974: 80ff.; Plett 1975: 150ff.). At the semantic level there are considerable discrepancies. For example, Plett defines oxymoron as a FSP derived via semantic subtraction (cf. above), whereas Dubois et al. (1974: 200) derive it via semantic substitution:

(14)

Cette obscure clarté qui tombe des étoiles

(This dark brightness which falls from the stars)(P. Corneille, Le Cid IV.3. 1273; G. Griffe: Corneille. Le Cid. Bordas 1965: 88)

There are more examples for discrepancies at the semantic level:

Dubois et al. consider only a small part of the classical tropes to be semantic figures (‘Métasémèmes’, 1974: 152ff.), while they treat most of them as extra-linguistic logical figures (‘Métalogismes’, 1974: 204ff.). Plett, however, treats all tropes as figures of semantic deviation. The view of Dubois et al. could be criticized as the problematic equation of semantic phenomena of natural languages with the semantic phenomena of formal logic.

Another example is provided by problematic attempts to reduce semantic FSP like metaphor, metonymy and synecdoche to one basic type (e.g. metaphor to a double synecdoche, cf. Dubois et al. 1974) or to one linguistic dimension (e.g. metaphor to the paradigmatic dimension, metonymy to the syntagmatic dimension, cf. Jakobson 1971). These attempts have plausibly been criticized as instances of reductionism (cf. Ricoeur 1975: 222ff.; Eggs 1994: 188ff.; cf. also Eco’s (1985: 169ff.) encyclopedic model of metaphor, metonymy and synecdoche).

Second, a great part of the traditional ‘figures of thought’ has not been systematically integrated in recent typologies (cf. the relatively short remarks in Todorov 1967: 110; Dubois et al. 1974: 218f.; 260ff.; Plett 1975: 302). Take, for example, ‘praeteritio’ (‘faked omission’), where the speaker mentions a fact which is harmful for his opponent while pretending at the same time not to refer to it. In the following example, Cicero pretends to omit the financial problems of his enemy Catilina while at the same time mentioning them:

(15)

Praetermitto ruinas fortunarum tuarum.

(I omit the ruin of your fortune) (Cicero, In Catilinam 1.6.14)

Or see the following example of another important ‘figure of thought’, namely, rhetorical question (‘interrogatio’):

(16)

What use is a smoke alarm with dead batteries?

Don’t forget it, check it.

(The Observer, 3.3.1991, quoted after Ilie 1994: 103)

The neglect of ‘figures of thought’ in modern typologies may be due to the fact that unlike other FSP they cannot easily be classified with the help of formal and structural features.

Third, the distinction of different linguistic levels from phonology to semantics should not obscure the fact that all FSP are strategies at the textual level, that is, discourse strategies. They are means to produce and enhance adequate sense relations within a given type of discourse. Therefore, in principle all FSP could be called ‘textual’ or ‘pragmatic’ figures. Only for the sake of analysis or clearness of presentation can we isolate FSP involving phonemes, morphemes, phrases, clauses and so on (this kind of criticism is acknowledged by Plett 1975: 149; 301f.).

Finally, it has to be criticized that structural typologies tend to neglect the fact that FSP should be considered as linguistic elements having certain communicative functions like clarification, stimulation of interest, aesthetic and cognitive pleasure, modification of the cognitive perspective, intensification or mitigation of emotions etc. Ideally, each structurally identified FSP should be assigned one or more functions as a complementary part of its description (for a first attempt cf. Plett 1985: 77, quoted after Knape 1996: 340). This is also important because one and the same FSP can have different functions according to the type of text in which it is used (cf. Knape 1996: 320, 339f.).

4. Aspects of a Critical Evaluation of FSP

Any attempt to distinguish rationally acceptable uses of FSP from more or less irrational uses has to define the concept of rationality. Before I try to do so, however, I would like to criticize some unrealistic expectations as far as the rational use of FSP is concerned. Some philosophers have postulated that rational discourse has to avoid all kinds of FSP. Take the example of John Locke (1975: 508; in: ‘An Essay Concerning Human Understanding’, 3.10.34):

‘But yet, if we would speak of Things as they are, we must allow, that all the Art of Rhetorick, besides Order and Clearness, all the artificial and figurative application of Words Eloquence hath invented, are for nothing else but to insinuate wrong Ideas, move the Passions, and thereby mislead the Judgment; and so indeed are perfect cheat: And therefore however laudable or allowable Oratory may render them in Harangues and popular Addresses, they are certainly, in all Discourses that pretend to inform and to instruct, wholly to be avoided’:

However, as my remarks on the problems of isolating a zero-variety of language have already made clear, it is simply not possible to refrain from using FSP. Of course, we can do without creating new (applications of) FSP. However, to speak or write without using any already established FSP like dead metaphors or dead metonymies, repetitions of sounds, words or phrases, parallel syntactic structures etc., is almost impossible. Even Locke in his severe criticism uses dead metaphors like ‘to move passions‘ and ‘to mislead judgment‘! (cf. Kittay 1987: 5). Nor would it be desirable to speak or write without using FSP. A postulate to present the ‘naked’ facts and nothing else – note that the postulate, too, makes use of a metaphorical expression! – is not only completely unrealistic, it also obscures the fact that FSP can make a positive contribution to the rationality of argumentation by making good arguments even stronger. Therefore, the application of stylistic strategies should not be deplored unless plausible reasons can be given that FSP have been applied in a fallacious way.

It is also impossible to ban or stigmatize specific types of FSP unconditionally. A prominent example is metaphor. Aristotle (together with other prominent authors) is often quoted as an authority for the prohibition of metaphors in rational discourse (Topics 139b, 34f.: ‘metaphorical expressions are always obscure’; transl. by Forster; cf. Pielenz 1993: 60, n. 12). However, Aristotle supports a much more sympathetic view of metaphor in his Rhetoric and Poetics, where he acknowledges its positive cognitive role[vii]:

‘To learn easily is naturally pleasant to all people, and words signify something: so whatever words create knowledge in us are the pleasantest…Metaphor most brings about learning, for when he calls old age “stubble”, he creates understanding and knowledge through the genus, since both old age and stubble are [species of the genus of] things that have lost their bloom’. Even in the Topics, he recognizes the fact that metaphors can make a certain contribution as to the better recognition of an object (Top. 140a 8-10).

Moreover, it has to be made clear that ‘metaphorical thought, in itself, is neither good nor bad; it is simply commonplace and inescapable’ (Lakoff 1991: 73, quoted after Pielenz 1993: 109, n. 141). The same metaphors can be used in a more or less rationally acceptable way, for example, ‘light’ and ‘darkness’ as metaphorical symbols for more or less respectable ideological concepts. Furthermore, different metaphorical domains, only some of which are rationally acceptable, are applied to the same concept: ‘love’ can be portrayed metaphorically as ‘war’, ‘madness’, but also as a ‘collaborative work of art’ or a ‘journey’ (Lakoff/Johnson 1980: 139ff.). Likewise, ‘anger’ can be linguistically portrayed in many different ways, for example, as ‘boiling liquid in a container’, ‘fire’, ‘explosion’ or ‘madness’ (Lakoff 1987: 397ff.).

Third, it is not plausible to ask for standards of the rational application of FSP which would be equally valid for all kinds of discussion, let alone for other types of discourse like poetry or narrative texts; here, I will mainly deal with FSP in argumentative texts. Walton’s remarks (1996: 15; cf. also Walton 1992: 19ff.) on the rationality of argumentation schemes equally apply to FSP. Plausibility judgments have to take into account if you are dealing with a quarrel, a TV talk show, a parliamentary debate, a scientific inquiry or a critical discussion in the sense of Van Eemeren/Grootendorst (1984, 1992). In a competitive type of discussion, it would not only be unrealistic, but also implausible to demand that even moderate verbal retaliations to previous attacks should be banned completely.

This would be in contradiction to widely accepted and rationally acceptable principles of fair play. But it is certainly right that in cooperative types of discussions all applications of FSP which block the goal of resolving a conflict of opinion by rational means should be prohibited.

Fourth, a distinction between acceptable and unacceptable bias has to be made (cf. Walton 1991). Neither is it unacceptable that FSP are used to enhance strong and relevant arguments nor would it be realistic to require that everybody should refrain from making their own standpoint as strong as possible. Only if a speaker uses FSP to hide a lack of critical distance in relation to his or her standpoint and tries to immunize their own standpoint, can FSP become fallacious.

How, then, can we distinguish rational and fallacious uses of FSP in a particular type of discussion? In what follows, I shall attempt a preliminary answer to this difficult question.

First of all, I will try to elaborate a concept of rationality which could be used as the basis of standards of evaluation for FSP. This concept cannot rely on foundationalist principles of rationality if it is designed to avoid the standard criticisms of being dogmatic (cf. Kopperschmidt 1980: 121ff., 1989: 104ff.; Van Eemeren/Grootendorst 1988: 279ff.). More particularly, it is very difficult to find ideas, concepts, theories which could be accepted as universally valid foundations of rational reasoning beyond reasonable doubt. Furthermore, philosophers like Wittgenstein (1975) have rightly pointed out that standards of rationality are relative to rules of language games and forms of life. Language games can be so different that the problem of incommensurability arises (cf. Fuller/Willard 1987, Luekens 1992). Moreover, Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca (1983) have correctly stressed the important role of the audience. Most of the time, it is hardly possible to evaluate a particular type of argumentation without taking into account that standards of rationality differ from audience to audience (cf., however, Siegel’s (1989) criticism of relativistic positions).

In the light of these problems I prefer to take a procedural approach in defining rationality. Thus I follow the lines of reasoning developed by scholars like Habermas (1981) and Van Eemeren/ Grootendorst (1984, 1992). Habermas’ normative concept of ‘discourse’ within an ideal speech situation and Van Eemeren/Grootendorst’s code of conduct for rational discussants are interesting approximations towards a procedural definition of rationality.

However, one important problemstill remains. The discursive procedures guaranteeing the rationality of the outcome of the discussion should be motivated in a way that the following question can be answered: why should people engage in a critical discussion in the first place? Here we ought to be realistic and should not simply postulate that rational people should behave rationally. So there should be some independent motivation. This motivation could be provided by a basic principle of rationality, which I would like to call ‘the conciliation of interests’ (cf. Kienpointner 1996a): a discussion can be called rational if and only if the outcome of the discussion leads to a conciliation of the interests of all the persons and groups involved. To a lesser degree, it could still be called rational if it at least makes some compromise between the respective parties possible. If persons who start a discussion have a realistic chance that their interests – including egoistic interests – will be at least partially taken into account, they could be willing to accept further and more detailed procedural rules. This is not a completely unrealistic assumption because all participants can now expect that the discussion will lead to some sort of compromise regardless of factors like power, gender, race or age.

Of course, such a conciliation of interests cannot be achieved in all the kinds of discussions mentioned above. Therefore, some of them are excluded as inherently irrational, for example quarrels (which is not to deny that quarrels can have useful effects for all involved persons sometimes, cf. Walton 1992). From the more general reflections above we can derive the following five global criteria for the rational acceptability of FSP:

– 1) FSP should contribute to the appropriateness of verbal contributions to the discussion, both at the informational and at the interpersonal and situational level (cf. Kienpointner 1996a and the comparable term ‘aptum’ in ancient rhetoric, e.g. Cic. or. 3.53).

More particularly, a contribution is appropriate at the informational level if it makes sure that the verbal presentation of the arguments is clear, understandable and to the point (cf. the maxims of Grice 1975 and Van Eemeren/Grootendorst 1992: 50ff.). It is appropriate at the interpersonal level if it is well adapted to the personal needs of the discussants, that is, if it is formulated in a polite, interesting, stimulating way. It is appropriate at the situational level if it is well adapted to the situational context of the discussion, that is, if it takens into account whether the discussion takes place in a public or a private context, in a tense or a relaxed atmosphere etc.

– 2) FSP should contribute to all dimensions of appropriateness.

This standard rules out the possibility that discussants use FSP with the goal of manipulating other discussants. True, in this case FSP can still be judged as highly efficient. However, they are no longer appropriate or rationally acceptable, because they are less than optimally informative and try to conceal personal interests instead of furthering a conciliation of interests. Moreover, also clear, relevant and honest formulations are not fully appropriate if discussants fail to present them in a way which makes them interesting and stimulating for the other participants of the discussion. In this case, even plausible arguments can fail to convince their audience because they appear in the form of boring and monotonous speech. And of course, it is not in the interest of all participants that strong arguments get ‘lost’.

– 3) FSP should not be used to hide a false belief or assumption.

In this case the speakers follow principles like Searle’s (1969) sincerity condition of speech acts and Grice’s (1975) maxim of quality[viii]. The only exceptions are cases where it is in the interest of the other participant(s) that the speaker uses FSP to conceal his or her real belief, for example, for reasons of politeness or to protect the feelings of the other discussant(s).

– 4) FSP should never be used to replace arguments.

This means that speakers should not use FSP to fake a substantial argument with the help of some argument-like formulation where there is none. Moreover, they should not be used to exaggerate the evidence for a certain standpoint in a way which immunizes the standpoint or even tries to preclude further discussion. It cannot be in the interest of all persons/groups involved that substantial arguments are not brought forward or that the possibility of a future revision of previous results of a discussion is prevented.

– 5) FSP should not be formulated in a way that they aggressively attack other participants in the discussion.

This criterium also holds if the aggressively attacked people are absent at the moment the respective formulations are used and the people which are present could be effectively persuaded with the help of the aggressive formulations. This is another obvious implication of the principle of the conciliation of interests: it concerns all persons involved, whether they are present or not at the moment when the respective FSP are employed.

More specific standards can only be developed if specific FSP are discussed on the basis of authentic examples, to which I will now turn. Due to lack of time, I will only provide a short survey of some rational and irrational ways of using metaphor. For the same reason, I will not try to provide an elaborate definition of metaphor, but content myself to state that I follow interactional and conceptual approaches to metaphor (cf. Black 1983, Ricoeur 1975, Lakoff/Johnson 1980, Eco 1985: 133ff.; Lakoff 1987). A brief, but basically acceptable characterization of metaphor is given by Lakoff/Johnson (1980: 5): ‘The essence of metaphor is understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another’.

Clear cases of irrational metaphors are the verbal attacks of political opponents in public speeches which use animal metaphors (or other kinds of degrading metaphors). It cannot be in the interests of all participants to dehumanize an opponent, even if he or she is sincerely believed to be some sort of monster. Nevertheless, the history of political rhetoric provides us with many examples of this abuse of metaphor, from antiquity to our times. Here are a few of them. Demosthenes, arguably one of the greatest orators of all times, did not refrain from calling his political opponent Aischines ‘a spiteful animal’ and a ‘monkey of melodrama’ (kivnado”.. aujtotragiko; “pivqhko”; Dem. 18.242; transl. by C.A. Vince/J.H. Vince, London: Heinemann 1963: 179). In his turn, Aischines addressed Demosthenes in a no less insulting way, for example, with ‘you curse of Hellas’ (with‘” JEllavdo” ajleithvrie; Aisch. 3.131; transl. by Ch.A. Adams; London: Heinemann 1968: 411). Cicero,

maybe the only rival of Demosthenes as the putatively greatest speaker of all time, thanked Jupiter for having saved Rome from ‘a so dreadful, so horrible, so hostile plague of the republic’ (tam taetram, tam horribilem tamque infestam rei publicae pestem; In Catilinam 1.11) as his political enemy Catilina. Moreover, Cicero called Catilina’s followers ‘the scum of the republic’ (sentina rei publicae; In Catilinam 1.12), although some of these were members of the Roman senate and even present during Cicero’s speech, as he himself admits (In Catilinam 1.8).

Unfortunately, these examples from antiquity cannot be dismissed with the remark that such FSP would be impossible in modern political speech. Nowadays, the dubious practice of denigrating political opponents with animal metaphors has found many successors, among them the leaders of Nazi-Germany. To quote just a few examples: in his infamous speech of 18th February 1943 in the Berliner Sportpalast, Joseph Goebbels (in: H. Heiber (ed.): Goebbels-Reden. 2 Bde. Düsseldorf 1971; Rede Nr. 17: 182f.) formulated violent antisemitic attacks with the help of dehumanizing metaphors, calling the Jews die Inkarnation des Bösen (the incarnation of evil), Dämon des Verfalls (demon of decay), eine infektiöse Erscheinung (an infectious phenomenon), diese Weltpest (this world plague).

But also politicians in democratic systems abuse metaphors in this way, for example, former U.S. President Ronald Reagan, who called the totalitarian leader of Lybia, Moamar Gaddhafi, a mad dog. As an Austrian, I am ashamed to add our present minister of foreign affairs, Wolfgang Schüssel, member of the conservative Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), to this list[ix]. Several Austrian journalists, who also made statutory declarations and against whom Schüssel took no action, testified that at a press conference (here in Amsterdam in June 1997) Schüssel called the chairman of the German Central Bank, Hans Tietmeyer, a real pig (eine richtige Sau; cf. PROFIL 28, 7.7.97, p. 21).

The same kind of criticism applies to racist or sexist metaphors in clichés, slogans, proverbs or other kinds of idiomatic expressions in everyday language which dehumanize racial minorities or women. Examples can be found in many languages[x] 264.

Another kind of criticism applies to metaphors which are too obscure or very hard to understand (cf. already Aristotle rhet. 1410b 31-32; Quintilian 8.6.14ff.). This does not mean, of course, that bold or difficult metaphors have to be avoided at all costs (cf. Aristotle rhet. 1412a 9-14; Cicero or. 3.160) or in all types of discourse. In poetry, obscure metaphors can even be appreciated as a virtue of style (cf. Eco 1985: 176ff.). Moreover, ‘bold’ metaphors need not always be difficult to understand or far-fetched. Weinrich (1976: 295ff.) correctly remarks that the very concept of ‘distance’ between the two conceptual spheres which are mapped onto each other is 1) metaphorical itself (which again shows that we cannot escape metapher even when we are talking about metaphors) and 2) has no direct connection with the degree of ‘boldness’ of metaphors. Weinrich argues that common everyday metaphors like Redefluß (flow of words) connect elements with greater semantic ‘distance’ than ‘bolder’ metaphorical connections like les lèvres vertes (the green lips) in Arthur Rimbaud’s poem ‘Métropolitain’ or schwarze Milch (black milk) in Paul Celan’s poem ‘Todesfuge’ (Weinrich 1976: 303ff.; note that Weinrich classifies ‘oxymoron’ as a subtype of metaphor). However, in everyday argumentation obscure metaphors should normally not be used. It should not happen that plausible arguments are not easily understood because they contain expressions which are hard to process.

A further kind of criticism concerns metaphors which are stilistically inadequate in relation to the situational context, that is, too refined, too vulgar or simply ridiculous. Especially ridiculous metaphors do not only not contribute to the force of potentially plausible arguments, but even prevent their effectiveness.

Trivial examples of metaphors which have gone wrong in this way are provided by slips of the tongue in public speeches, like the following example reported by Sigmund Freud (1974: 80): in the year 1908, a representative (Lattmann) tried to convince the German parliament (‘Reichstag’) to express the common will of the German people in an address to the emperor, William II., and intended to continue: ‘if we can do that in a way that truly respects the feelings of the emperor, we should do that without reserves‘ (‘wenn wir das in einer Form tun können, die den monarchischen Gefühlen durchaus Rechnung trägt, so sollen wir das auch rückhaltlos tun’). However, the speaker unwillingly produced a metaphor which not only expressed the opposite of what he wanted to say but was also ridiculous in the given institutional context; it caused laughter which went on for some minutes: ‘wenn wir das…tun können, so sollen wir das auch rückgratlos tun’ (lit. ‘if we can do that…we should do that spinelessly‘, that is, ‘we should act without backbone, in a bootlicking way‘).

Of course, in this case we are not dealing with an FSP as the result of a verbal strategy, but with a mistake, a deviation in the narrow sense of the word. But there are cases where metaphors cannot achieve their goal even if they are intentionally used by a participant in a discussion, for example, when they mix up several hardly compatible conceptual spheres.

The following dialogue provides an example: in a debate which took place in the year 1978, the opponents were two German physicians, J. Hackethal and C.F. Rothauge. At that time, Hackethal was well known for his severe criticism of orthodox medicine. Rothauge accuses Hackethal of exaggerating his criticism beyond reasonable limits. To enforce his arguments, Rothauge combines a traditional metaphor with an innovative extension of the conceptual sphere of the traditional metaphor (cf. Pielenz 1993: 111ff.) and a comparison (SPIEGEL 40.2 (1978): 155):

(17)

ROTHAUGE: Ich kann dazu nur sagen, daß Herr Kollege Hackethal in der Manier eines Michael Kohlhaas nun hier das Kind mit dem Bade ausschüttet und dann noch die Mutter mit der Badewanne totschlägt. (The only thing I can say is that my colleague, Mr. Hackethal, acting like a second Michael Kohlhaas, is now throwing out the baby with the bathwater and then goes on to kill the mother with the bathtub)

………..

HACKETHAL: …zu Zeiten von Kohlhaas gab’s noch keine Badewannen….

(…in Kohlhaas’ days, bathtubs had not been invented…)

To demonstrate that Hackethal overstates his point, Rothauge not only uses the traditional metaphor to throw out the baby with the bathwater, but also hyperbolically extends it (to kill the mother with the bathtub; on extensions of metaphorical domains cf. Lakoff/Johnson 1980: 139; Pielenz 1993: 71ff.). Adding a comparison of Hackethal with the legendary M. Kohlhaas (1500-1540, a German merchant who became a symbol of fanatic struggles for justice without success), Rothauge himself comes close to overstatement. Therefore, he can be criticized of combining to many semantic spheres which are only partially compatible and thus forming a somehow inconsistent whole. This is recognized by his opponent Hackethal who tries to ridicule Rothauge’s remark by pointing out the internal inconsistency of his FSP.

What, then, are clear cases of rationally used metaphors? The treatment of irrational metaphors has already partially answered this question: as good metaphors are the opposite of bad ones, they have to avoid aggressive attacks and have to be easily understandable, clear and consistent. But more than this, they should also provide interesting cognitive insights and shed new light upon the debated problem. The following metaphorical argument from an article on Martin Luther King seems to be a good candidate:

(18)

It is only because of King and the movement he led that the U.S. can claim to be the leader of the “free world” without inviting smirks of disdain and disbelief…How could America have convincingly inveighed against the Iron Curtain while an equally oppressive Cotton Curtain remained draped across the South? (Jack E. White, in TIME Magazine 151.15 (1998): 88)

In this passage, the relevance of White’s argument is guaranteed by a warrant which is called the rule of justice by Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca (1983: 294; Kienpointner 1992: 294ff.). According to this type of warrant, persons, groups or social institutions who can be subsumed under the same category have to be treated equally: all human beings, for example, have to be granted fundamental human rights by the respective authorities. It can hardly be denied that violations of the human rights of black people were widespread in the U.S. even after the Supreme Court struck down racial segregation in 1954. Moreover, these offenses were comparable with at least some of the severe violations of human rights in the former Eastern block. One could reply that the total amount of violations of basic human rights was higher in the Eastern block than in the U.S. and that, therefore, the rule of justice cannot apply. But this remark would come close to the fallacy of the two wrongs: even a higher rate of violations of human rights in the east could not justify violations of human rights in the west. Therefore, White’s argument can be judged plausible because a U.S. criticism of human-rights offenses in the former Communist countries could hardly have been consistent without a commitment to high standards of civil rights in America.

To enhance the strength of his argument, White 1) formulates it as a rhetorical question and thus increases the direct involvement of the reader, and 2) uses a dead metaphor (Iron Curtain) together with a creative metaphor (Cotton Curtain) and thus increases the weight of his argument according to the rule of justice. Recall that the latter asks for identical treatment of persons or institutions belonging to the same category. Now the new metaphor (Cotton Curtain) makes it cognitively much easier to perceive the oppressive treatment of black people in the U.S.A. and the oppressive treatment of citizens in the Communist states as parallel cases. If my analysis of White’s argument is acceptable, this has been an example of a rational use of metaphor. Unfortunately, most arguments involving metaphors neither belong to the clearly rational nor the clearly irrational cases. They lie somewhere in between and evaluative assessments will vary according to the cultural and political background of the hearers/readers. I wish to conclude this section providing a few examples of borderline cases: in newspaper reports, editorials, comments and political speeches the Hong Kong handover in July 1997 was metaphorically portrayed quite differently by authors and speakers with a western and/or a democratic background and those of a Chinese and/or a communist background, respectively. These two groups include on the one hand western journalists, British ex-governor Chris Patten or members of the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong like Martin Lee, and on the other hand mainland-Chinese journalists, representatives of the newly established Provisional Legislative Council of Hong Kong like Tung Chee Hwa or the President of the People’s Republic of China, Jiang Zemin[xi]. Here are some metaphors used by the opposed parties. On the one hand, in the German and Austrian press and in media from the English and French speaking world, Hongkong is often metaphorically called ‘a jewel’ or the ‘crown jewel’ (‘das Kronjuwel’, ‘ein Juwel’ cf. Th. Sommer, ZEIT Punkte 3 (1997): 72; 73; cf. similarly: Tiroler Tageszeitung 148 (1997): 7; H.L. Müller in Salzburger Nachrichten June 28 (1997): 1), ‘one of the safes of the planet’ (‘un des coffres-forts de la planète’; Frédéric Bobin in LE MONDE June 29./30 1997: 12), ‘a bride’ (‘the bride Hongkong…is bringing…the biggest dowry since Cleopatra’: ‘die Braut Hongkong…bringt …seit Kleopatra die größte Mitgift’; Th. Sommer, ZEIT Punkte 3(1997): 73), ‘the goose which lays golden eggs’ (‘die Gans, die…die goldenen Eier legt’; ibid. 76; cf. similarly H. Bögeholz in ainfo (= the newsletter of the Austrian section of Amnesty International) July (1997): 6; B. Voykowitsch in DER STANDARD July 1 (1997): 30), Martin Lee claims that ‘Beijing is putting a noose around the goose’s neck and still expecting it to lay golden eggs’ (TIME July 1 (1997): 24): – the future of Hong Kong is often conceived of pessimistically, for example, some fear that ‘Hong Kong could become the Miami of China, dominated by the underworld, awash in dirty and laundered money and swamped with migrants from China’ (TIME July 1 (1997): 26);

– Great Britain is still sometimes referred to as Hong Kong’s ‘motherland’ (‘Mutterland Großbritannien’; U.J. Heuser, ZEIT Punkte 3 (1997): 78); – the People’s Republic of China is called ‘the giant in the north’ (‘der Koloß im Norden’; ibid. 81), ‘the only master of the area’ (‘Pékin a démontré que la Chine était désormais le seul maître des lieux’; Francis Deron in LE MONDE July 3 1997: 4), the Provisional Legislative Council is called a ‘shadow parliament’ (‘Schattenparlament’, ainfo July (1997): 7), whose members were ‘handpicked’ by Beijing (‘handverlesen’; ibid. 8), the members of the pro-democratic camp are said to be unsure how to fight ‘an adversary as formidable as mainland China’ (TIME July 1 (1997): 24).

On the other hand, in Chinese sources, – the People’s Republic of China is called Hong Kong’s ‘motherland’ (China Today July (1997): 7), the handover is ‘the return of Hong Kong to the motherland’ and is ‘erasing a century-old national humiliation’ (ibid.), the Chinese people struggled to wipe out their national humiliation (ibid.); the interests of Hong Kong and China are ‘intricately linked and intertwined’ (Tung Chee Hwa in his speech at the Special Administrative Region Establishment Ceremony, in: South Morning Post July 2 (1997): 8). In the same vein, Chinese President Jiang Zemin calls ‘Hong Kong’s return to the motherland…a shining page in the annals of the Chinese nation’ (South Morning Post July 2 (1997)); – Tung Chee Hwa writes that the inhabitants of Hong Kong are finally ‘the masters of our own house’ (NEWSWEEK May-July (1997): 48) and calls the last-minute pro-democratic reforms of Britain ‘political baggage’ (ibid. 49); – the future of Hong Kong is seen optimistically (e.g. by Tung Chee Hwa in his speech at the Special Administrative Region Establishment Ceremony: ’We can now move forward… to lead Hong Kong to new heights’; South Morning Post July 2 (1997): 8), ‘Hong Kong and the mainland will move forward together, hand in hand’ (ibid.).

These two groups of metaphors follow the criteria for a rational use of FSP I stated above, at least to a certain degree : all in all, they are not aggressively dehumanizing the political opponent and they are clear and consistent. At the same time, the examples show that both groups of metaphors are strongly biased to one side of the question. However, if you do not share the cultural and political values which are presupposed and metaphorically reinforced by the respective parties, it becomes quite difficult to judge whether either sort of bias could be rationally justified or not (remember that bias in itself is not a sufficient criterium for a fallacious use of FSP). Perhaps one could argue that metaphors which do not exclusively portray Hong Kong as part of the western culture on the one hand or part of the Chinese tradition on the other would be more rational insofar they arguably are more in the interest of all parties involved. Luckily, such metaphors have been used, too: for example, both Chinese President Jiang Zemin and Britain’s Foreign Minister, Robin Cook, have metaphorically called Hong Kong a ‘bridge’ between China, Britain and the rest of world (cf. South Morning Post July 2 (1997); DER STANDARD July 1 (1997): 2). Let’s hope that this metaphor, rather than more aggressive ones, will shape future discursive treatments of this important political issue and the resulting policies…

5. Conclusion

The remarks I have made in this paper have more often than not been only sketchy (esp. in sections 3 and 4). Obviously, there is still a great deal more work to do before a full answer to the three basic questions concerning the definition, classification and critical evaluation of FSP can be given. I would like to finish with a short list of open problems. Definitions of FSP should try to solve the difficult question of how to elaborate a clearer distinction between creative and conventionalized uses of FSP (e.g. creative and dead metaphors). Typologies of FSP should apply the standards of explicitness and demarkation achieved in recent approaches while integrating the so far missing classes of FSP which have traditionally been classified as figures of thought. As far as the evaluation of FSP is concerned, one of the goals should be the formulation of complete and detailed lists of critical questions as to the rational use of FSP, very much in the same way as these critical questions have already been elaborated for argumentation schemes (cf. Van Eemeren/Kruiger 1987, Kienpointner 1996a, Walton 1996).

NOTES

i. Note that I use of this term in its broadest sense, including both tropes and FSP in the narrow sense, that is, figures of diction and figures of thought.

ii. Similarly, Ricoeur remarks (1975: 25): ‘Il n’y a pas de lieu non métaphorique d’où l’on pourrait considerer la métaphore, ainsi que toutes les autres figures, comme un jeu déployé devant le regard’.

iii. ‘Eigentlich ist alles Figuration, was man gewöhnliche Rede nennt’; quoted after Knape 1996: 293.

iv. ‘Sed inter conformationem verborum et sententiarum hoc interest, quod verborum tollitur, si verba mutaris, sententiarum permanet, quibuscumque verbis uti velis’; Cic. or. 3.200.

v. The four operations are: addition, subtraction, substitution, permutation (‘adiectio, detractio, immutatio, transmutatio’; cf. Quintilian inst. orat. 1.5.38).

vi. I will not deal with graphemics here.

vii. Cf. rhet. 1410b 10-15; translation by G.A. Kennedy: Aristotle: On Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press 1991: 244; cf. also Arist. poet. 1459a 5-8; Ricoeur 1975: 49; Eco 1985: 151; Kittay 1987: 2ff.

viii. For a synthesis of the approaches of Searle and Grice see Van Eemeren/Grootendorst 1992: 51.

ix. Not to mention the Austrian right wing politician Jörg Haider, who frequently uses dehumanizing metaphors as a political strategy, cf. Scharsach 1992: 214f.

x. The following examples are taken from English, French and German: there’s a nigger in the woodpile, parler petit nègre (to talk gibberish, lit.: to talk little negroe), daherkommen wie ein Zigeuner (to have a scruffy appearance, lit.: to come along like a gypsy); cf. also the widespread habit of calling women chicken, cows, bitches; poules, lièvres, souris; Hasen, Bienen, Bären; for racist metaphors in the media cf. e.g. Van Dijk 1993: 263f.

xi. I would like to thank my colleague Shi Xu, University of Singapore, for allowing me to use part of his English data concerning the Hong Kong handover.

REFERENCES

Aristotle (1959). Rhetoric. Ed. by W.D. Ross. Oxford: Clarendon.

Aristotle (1960). Posterior Analytics. Ed. and transl. by H. Tredennick. Topica. Ed. and transl. by E.S. Forster. London: Heinemann.

Aristotle (1965). Poetics. Ed. by R. Kassel. Oxford: Clarendon.

Aristotle (1958). Topics. Sophistical Refutations. Ed. by W.D. Ross. Oxford: Clarendon.

Black, M. (1983). Die Metapher. In: A. Haverkamp (Hg.): Theorie der Metapher (pp. 55-79), Darmstadt: Wiss. Buchgesellschaft.

(German Translation of: M. Black: Metaphor. In: Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 55 (1954), 273-294).

Cicero (1951). De oratore. Ed. by A.S. Wilkins. Oxford: Clarendon.

Coseriu, E. (1956). La creación metafórica en el lenguaje. Montevideo: Univ. de la República.

Coseriu, E. (1958). Sincronia, diacronia e historia. Montevideo: Univ. de la República.

Coseriu, E. (1971). Thesen zum Thema ‘Sprache und Dichtung’. In: W.D. Stempel (Hg.): Beiträge zur Textlinguistik (pp. 183-188), München: Fink.

Coseriu, E. (1994). Textlinguistik. Tübingen: Francke.

Dubois, J. et al. (1974). Allgemeine Rhetorik. München: Fink (German Translation of: J. Dubois et al.: Rhétorique générale. Paris Larousse 1970).

Eco, U. (1995). Semiotik und Philosophie der Sprache. München: Fink (German Translation of: U. Eco: Semiotics and the philosophy of language. London: Macmillan 1984).

Eggs, E. (1994). Grammaire du discours argumentatif. Paris: Kimé.

Freud, S. (1974). Zur Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens. Frankfurt/ M: Fischer.

Fuller, S. & Ch.A. Willard (1987). In Defense of Relativism: Rescuing Incommensurability from the Self-Excepting Fallacy. In: F. Van Eemeren et al. (eds.), Argumentation. Perspectives and Approaches (pp. 313-320), Dordrecht: Foris.

Gibbs, R. (1994). The Poetics of Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Grice, H.P. (1975). Logic and Conversation. In: P. Cole & J.L. Morgan (eds.), Syntax and Semantics 3 (pp. 41-58), New York: Academic Press.

Habermas, J. (1988). Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns. 2 Bde. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Ilie, C. (1994). What Else Can I Tell You? A Pragmatic Study of English Rhetorical Questions as Discursive and Argumentative Acts. Stockholm: Almqvist &Wiksell.

Jakobson, R. (1960). Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics. In: Th.A. Sebeok (ed.). Style in Language (pp. 350-377), Cambridge/ Mass.: MIT-Press.

Jakobson, R. (1971). Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances. In: R. Jakobson, Selected Writings. Vol. 2. (pp. 239-259), Mouton: The Hague.

Kienpointner, M. (1992). Alltagslogik. Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog.

Kienpointner, M. (1996a). Vernünftig argumentieren. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Kienpointner, M. (1996b). Whorf and Wittgenstein. Language, World View and Argumentation. In: Argumentation 10: 475-494.

Kienpointner, M. (1997). Sprache, Dichtung, Kreativität. Bemerkungen zu Eugenio Coserius Thesen zu Sprache und

Dichtung. In: M. Sexl (Hg.), Literatur? (pp. 69-90), Innsbruck: StudienVerlag.

Kittay, E.F. (1987). Metaphor. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kloepfer, R. (1975). Poetik und Linguistik. München: Fink.

Knape, J. (1996). Figurenlehre. In: G. Ueding (Hg.), Historisches Wörterbuch der Rhetorik. Bd. 3. (pp. 289-342), Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Kopperschmidt, J. (1980). Argumentation. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Kopperschmidt, J. (1989). Methodik der Argumentationsanalyse. Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog.

Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, Fire and Dangerous Things. Chicago: Chicago Univ. Press.

Lakoff, G. (1991). War and Metaphor. The Metaphor System Used to Justify War in the Gulf. In: P. Grzybek (ed.), Cultural semiotics: Facts and Facets (pp. 73-92), Bochum: Brockmeyer.

Lakoff, G. & M. Johnson (1980). Metaphors we Live by. Chicago: Chicago Univ. Press.

Lausberg, H. (1960). Handbuch der literarischen Rhetorik. München: Hueber.

Leech, G.N. (1966). A Linguistic Guide to English Poetry. London: Longmans.

Locke, J. (1975). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Ed.by P.H. Nidditch. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Geert-Lueke Lueken (1992). Inkommensurabilität als Problem rationalen Argumentierens. Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog.

Marouzeau, J. (1935). Traité de stylistique. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Perelman, Ch. & L. Olbrechts-Tyteca (1983). Traité de l’argumentation. La nouvelle rhétorique. Bruxelles: Editions de l’université.

Pielenz, M. (1993). Argumentation und Metapher. Tübingen: Narr.

Plett, H.F. (1975). Textwissenschaft und Textanalyse. Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer.

Plett, H.F. (1985). Rhetoric. In: T.A. Van Dijk (ed.), Discourse and Literature (pp. 59-84), Amsterdam.

Quintilianus (1970). Institutio oratoria. Ed. by M. Winterbottom. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Ricoeur, P. (1975). La métaphore vive. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Scharsach, H.H. (1992). Haiders Kampf. Wien: Orac.

Searle, J. (1969). Speech Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Siegel, H. (1989). Epistemology, Critical Thinking and Critical Thinking Pedagogy. In: Argumentation 3.2, 127-140.

Spillner, B. (1974). Linguistik und Literaturwissenschaft. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Spitzer, L. (1961). Stilstudien. Bd 2. München: Hueber.

Thucydides. (1952). The History of the Peloponnesian War (Richard Crawley, Trans.). Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Todorov, T. (1967). Littérature et signification. Paris: Larousse.

Ueding, G. & B. Steinbrink (1986). Grundriß der Rhetorik. Geschichte – Technik -Methode. Stuttgart: Metzler.

Van Dijk, T.A. (1980). Textwissenschaft. München: dtv.

Van Dijk, T.A. (1993). Elite Discourse and Racism. London: Sage.

Van Eemeren, F. & R. Grootendorst (1984). Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussions. Dordrecht: Foris.

Van Eemeren, F. & R. Grootendorst (1988). Rationale for a Pragma-Dialectic Perspective. In: Argumentation 2.2, 271-291.

Van Eemeren, F. & R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, Communication and Fallacies. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Van Eemeren, F. &T. Kruiger (1987). Identifying Argumentation Schemes. In: F. Van Eemeren et al. (eds.), Argumentation. Perspectives and Approaches (pp. 70-81), Dordrecht: Foris.

Verschueren, J. (1998). Understanding Pragmatics. London: Arnold.

Walton, D. (1991). Bias, Critical Doubt and Fallacies. In: Argumentation and Advocacy 28, 1-22.

Walton, D. (1992). The Place of Emotion in Argument. University Park, PA: Pennsylvaina State Univ. Press.

Walton, D. (1996). Argumentation Schemes for Presumptive Reasoning. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Ward, G.L./J. Hirschberg (1991). A Pragmatic Analysis of Tautological Utterances. In: Journal of Pragmatics 15.6, 507-520.

Weinrich, H. (1976). Sprache in Texten. Stuttgart: Klett.

Weydt, H. (1987). Metaphern und Kognition. In: J. Lüdtke (Hg.), Energeia und Ergon. Studia in honorem Eugenio Coseriu. Bd 3. (pp. 303-311), Tübingen: Narr.

Wittgenstein, L. (1975). Philosophische Untersuchungen. Frankfurt/ M.: Suhrkamp.

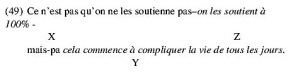

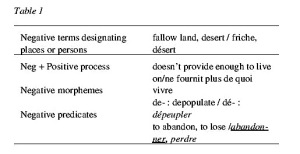

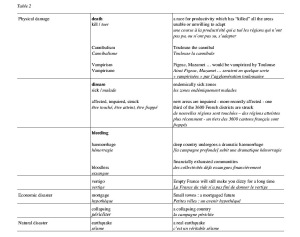

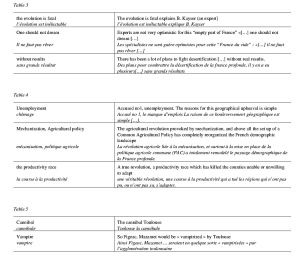

The use of simplement, I will be dealing with is often viewed as a weaker version of the adversative marker mais (known as ‘mais-pa’). Simplement, however, will not be appropriate in all the environments where mais-pa is to be found; furthermore, it affects cohesion in different ways, as it calls for different types of continuation, gives rise to a different situation schema and context construction, and lends itself to strategic uses of its own. In this paper I will attempt to clarify those various aspects, which, following Anscombre and Ducrot, I will construe in procedural terms, or in terms of semantic constraints on interpretation.

The use of simplement, I will be dealing with is often viewed as a weaker version of the adversative marker mais (known as ‘mais-pa’). Simplement, however, will not be appropriate in all the environments where mais-pa is to be found; furthermore, it affects cohesion in different ways, as it calls for different types of continuation, gives rise to a different situation schema and context construction, and lends itself to strategic uses of its own. In this paper I will attempt to clarify those various aspects, which, following Anscombre and Ducrot, I will construe in procedural terms, or in terms of semantic constraints on interpretation.