ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Final But Not Infallible. Two Dimensions Of Judicial Decisions

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

One of the forms of rule skepticism, found both in legal practice and in legal theory, learns that the law is what the courts say it is and nothing more. In his study The Concept of Law (1961) Hart criticizes this form of rule skepticism. Decisions of a court he says, are statements with a certain authority making them final but not also infallible. To clarify this, Hart uses the example of an umpire in a game. In a game the judgements of an umpire – for instance about the scoring – have a certain authority. His judgements are given, by the secondary rules of the game, a status which renders them unchallengeable. In this sense it is true, says Hart, that for the purposes of the game ‘the score is what the scorer says it is’. But it is important to see that there is a scoring rule and it is the scorer’s duty to apply this rule as best he can.[i] It is this scoring rule which makes decisions of the umpire, though final, not infallible, for this scoring rule offers reasons for criticizing the decision.

According to Hart the same is true in the law. Like the umpire’s decision in a game, the decisions of a judge like ‘X is guilty’ or ‘X has a right’ are – up to a certain point – final. But, like the umpire in a game, the judge has an obligation to apply the rules correctly according to the secondary rules in a legal system.[ii] As a result judicial decisions are fallible.

Austin (1962) made similar observations about the nature of judicial decisions. He argues that if it is established that a performative utterance is performed happily and in all sincerity, that still does not suffice it beyond the reach of all criticism. It may always be criticized in a different dimension, a dimension comparable with the true/false criterium used to evaluate constative utterances: ‘Allowing that, in declaring the accused guilty, you have reached your verdict properly and in good faith, it still remains to ask whether the verdict was just, or fair’ (1962:21)

Since the publications of Austin en Hart, the observations about the character of judicial decisions give rise to the question what type of speech act is involved. Both in legal theory and in argumentation theory it is posed as a problem whether these speech acts are, or are to be reconstructed, as declarative, or as assertive speech acts. For on the one hand, the judge declares that somebody is guilty, but on the other the judge justifies that this decision is right according to the law. And this justification is a reason to reconstruct the decision as an assertive or, to be more precise, as a standpoint in a context of a discussion.

In this paper, I want to discuss the problem of the speech act character of a judicial decision within the framework of the pragma-dialectical argumentation theory. My basic starting point is that it is a misunderstanding to treat speech acts in judicial decisions as either assertive or declarative speech acts. I think that, for an adequate analysis of the speech act, one has to make a distinction between at least two discussions in a legal process and related to this distinction different functions of the speech act in a final judicial decision.

I will proceed as follows. First, I will discuss the merits and demerits of reconstructing a final judicial decision as the mixed speech act called assertive-declaration. Then, I will differentiate between two discussions and two types of speech acts in a legal process. Finally, I will discuss how these two different types of speech acts can be reconstructed as a standpoint.

2. Final judicial decisions as an assertive-declarative speech act

For those who are familiar with Speech Act Theory, it will be clear that it is possible to analyse a judicial decision as ‘X is guilty’ as the combination of an assertive and a declarative speech act. Searle (1979) contends that at least some members of declarative speech acts overlap with members of the class of assertive speech acts. These assertive-declarative speech acts have two illocutionary points. First, they have the assertive illocutionary point, according to which a speaker succeeds in achieving on a proposition P (X is guilty), if and only if he represents the state of affairs that P as actual. Second, they have the declarative illocutionary point, according to which a speaker succeeds in achieving on a proposition P if and only if he brings about the state of affairs that P.

Searle illustrates this double character of the assertive-declarative speech act with the example of the umpire who decides: ‘You are out’. In certain institutional situations, he explains, we not only ascertain facts but also need an authority to lay down a decision as to what the facts are:

Some institutions require assertive claims to be issued with the force of declarations in order that the argument over the truth of the claim can come to an end somewhere and the next institutional steps which wait on the settling of the factual issue can proceed (Searle 1979).

So, in Searle’s perspective an assertive declaration can be simultaneously conceived as a representation of a state of affairs (which is in keeping with the assertive point) and as the constitution of a state of affairs (which is in keeping with the declarative point). In Searle’s interpretation of the relationship between the two illocutionary points, the rule for assertive declarations would be as follows:

A speaker succeeds in achieving with respect to a proposition P the assertive illocutionary point if and only if he represents the state of affairs that P as actual, and, in addition, he succeeds in achieving with respect to P the declarative illocutionary point if and only if he brings about the state of affairs that P (Ruiter 1993: 61).

According to Ruiter (1993) this rule has paradoxal implications. Imagine, he says, that a judge decides ‘X is guilty’, with regard to a situation in which he is not guilty according to the law. On Searle’s account it must be accepted that the judge’s false decision is not only unchallengeable but actually true. For under the second part of the above rule, ‘X is guilty’ becomes a state of affairs owing to the judge’s decision, in consequence of which the assertion that ‘X is guilty’ is true under the first part.

Ruiter tries to solve this problem by making a distinction between the institutional world and the surrounding world of utterance. In the institutional world the judge’s decision ‘X is guilty’ constitutes the institutional fact that ‘X is guilty’. When this decision fails on the assertive point in the surrounding world of utterance, the fact still counts as an institutional fact.

3. Two discussions in a judicial decision

The main problem with Ruiters solution is that the difference between the ‘institutional world’ and the ‘surrounding world of utterance’ is rather general and not very clear. Another way to analyse the speech act (or speech acts) in a judicial decision – as I said in my introduction – is to make a distinction between different discussions in a legal process and related to these discussions different functions of a speech act like ‘X is guilty’.

Let me start with the analysis Feteris (1989) proposed. Following the pragma-dialectical model of a discussion, she gives a reconstruction of judicial decisions. In this model four stages are distinguished. At the confrontation stage, it is established that there is a dispute. A standpoint is advanced and questioned. At the opening stage, the decision is taken to attempt to resolve the dispute by means of a regulated argumentative discussion between a protagonist and an antagonist. At the argumentation stage, the protagonist defends his standpoint and the antagonist asks for more argumentation from him if he has further doubts. Finally at the concluding stage, it is established whether the dispute has been resolved because the standpoint or the doubt concerning the standpoint is being retracted.

Feteris locates the judicial decision in the concluding stage of the discussion between two parties in a process. If the facts stated can be considered as established facts and the judge has decided that there is a legal rule which connects the claim to these facts, the judge will grant the claim. But the secondary rules of a legal system do not only oblige a judge to give a decision in the dispute, but also to give a justification for this decision. The parties have a right to know which considerations underlie the decision. When a party does not agree with the decision, he can appeal the decision on the basis of the argumentation given in the justification.

On the basis of this analysis, Feteris concludes that a final decision of a judge can be seen as an assertive-declarative speech act. She proposes to reconstruct this speech act as an assertive speech act because the judge is bound to the acceptability of the propositional content of the speech act.

Relating the question of speech act character of a final decision to a stage in a legal discussion is an important step forward in solving the problem, but it leaves a few questions unanswered. The first question is: how can we conceive the final decision both as a standpoint of the judge – an assertive – and as a part of the concluding stage of the discussion between the parties? For in the concluding stage it is established whether the dispute has been resolved. Why should a standpoint and argumentation be part of a concluding stage? For an answer to this question, I think, we must make a distinction between at least two discussions in legal decision making. When we make this distinction there is another way to solve the paradoxes concerned to the assertive-declarations as observed by Ruiter.

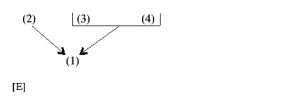

The first discussion is the one between the parties. In this discussion the two parties defend and criticize a standpoint and the judge is a third party to the dispute. In this discussion the decision of the judge is part of the concluding stage where the discussion is brought to an end. The judge has the extra linguistic position to declare that somebody is guilty. This utterance of the judge must be reconstructed as a declarative speech act, for the fact that the judge says that ‘X is guilty’ brings about the state of affairs that ‘X is guilty’.

This reconstruction is in line with the pragma-dialectical theory about a critical discussion and the difference that is made between resolving a difference of opinion on the one hand and settling a dispute on the other. The declaration of the judge, seen from the perspective of the discussion between parties, is not a part of a critical discussion but a form of dispute settlement. So, the declarative is legal according to the rules.

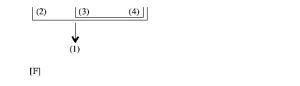

As Feteris (1989) points out, a judge does not only declare that somebody is guilty, the judge also justifies why he is guilty according to established facts and legal rules. In other words, the judge defends the standpoint that the decision is acceptable. This standpoint is not a part of the discussion between the parties, but a part of the discussion between the judge and the parties, or between the judge and other explicit or implicit antagonists. In this discussion the standpoint of the judge is part of the confrontation stage. And, since the argumentation the judge gives is meant to convince the parties that his standpoint is right according to the law, his standpoint and argumentation are part of a critical discussion aimed at resolving a difference of opinion. When a party does not agree with the decision, he can appeal the decision on the basis of the argumentation given in the justification. And then, there is an explicit discussion between a party and the judge.

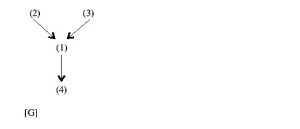

So, when we reconstruct the final decision of the judge both as a part of a concluding stage in the discussion between the parties and as a part of a confrontation stage in the discussion between the judge and one or more parties, the decision can be reconstructed both as a declarative and an assertive.

Does this resolve the paradox that Ruiter observes? I think it does. For the judge’s decision that somebody is guilty constitutes the institutional fact of his being guilty in the concluding stage of the discussion between parties. The decision has of course success of fit on the assertive illocutionary point only if he really is guilty according to the law. But if X is not guilty, he will nevertheless institutionally be guilty as long as the judge’s decision is not redressed. Though the falsity of assertion ‘X is guilty’ may offer a reason for invalidating it, it remains valid unless it is invalidated. In this way a false representation of a state of affairs counts legally as a state of affairs notwithstanding its lack of correspondence with reality.

In answering the question whether the decision is a declarative or an assertive, I have said that it is a declarative from one point of view and a standpoint from another point of view. Untill now it was understood that the speech act advancing a standpoint is an assertive speech act. But the next question is: what type of assertive is involved? I will now discuss some implications of the pragma-dialectical characterization of the assertive speech act ‘advancing a standpoint’ as given by Houtlosser (1994 and 1995), for the standpoint character of legal decisions. Houtlosser characterizes the speech act advancing a standpoint as a complex assertive that is at a higher textual level than the sentence connected to an expressed opinion that is confronted (or assumed to be confronted) with doubt or contradiction on the part of a critical listener. According to the essential condition, advancing a standpoint counts as taking the responsibility for a positive or negative position in respect of an expressed opinion, i.e. as assuming an obligation to defend this position in respect of the expressed opinion if called upon to do so. In principle, Houtlosser explains, the assertive speech act advancing a standpoint is related to assertive speech acts, but it can also be related to non-assertive speech acts. In the latter case, the expressed opinion consists of an assumption concerning the acceptability of a speech act that has become the object of contention in a debate or a text.

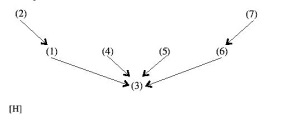

What are the consequences of this characterization of a standpoint for the discussion between the judge and a party in a legal discussion? Let us look at the example where the judge finds X guilty of murder and one of the arguments is that X had the intention to murder his wife. According to Houtlosser we can analyse this example as follows. The judge asserts that X is guilty of murder. This assertive presupposes its own acceptability. In his argument ‘X had the intention to murder his wife’ the judge reacts to or anticipates on the criticism of the accused (‘it was self-defense’) by supporting the disputed presupposition that his assertive is acceptable. In doing so, he makes it function as a standpoint. He supports his standpoint with an argument supporting the propositional content of the assertive. According to Houtlosser we can reconstruct the standpoint as follows: ‘It is my standpoint that the assertion that X is guilty of murder is acceptable’

This example shows how we can reconstruct the assertive of the judge as a standpoint in the discussion between the judge and one of the parties in a process. What about a declarative of the judge in the concluding stage of the discussion between parties? Is it possible that this speech act – so to say – develops into a standpoint? I that is possible. As I have said, Houtlosser explains that the assertive speech act advancing a standpoint can be related to non-assertive speech acts. In these cases, the acceptability of the non-assertive speech act has become the object of discussion. Let us look at the example where the judge finds X guilty of murder and one of the arguments is that X murdered his wife in London. How can we reconstruct this argumentation? Let us start by analyzing the utterance ‘X is guilty of murder’ as a declaration in the concluding stage of the discussion between the parties. As we have seen, it is a necessary condition for a succesfull performance of this speech act that the judge has the extra linguistic position to declare something. Let us assume that it was this aspect of the speech act, that was (or was expected to be) criticized by the accused in saying that the judge has no jurisdiction in this case. By criticizing the acceptability of the judge’s (expected) declarative, the accused turns the presupposition that the declarative could be succesfully performed into an issue for discussion.[iii] The judge reacts to or anticipates on this criticism supporting the disputed presupposition that he could perform the declarative because he had jurisdiction. He supports his standpoint with an argument relating to the conditions for performing a declarative. The standpoint of the judge can be reconstructed as ‘It is my standpoint that the declaration that X is guilty of murder is acceptable’.

4. Conclusion

In this paper I have discussed some problems of the speech act character of a judicial decision. I have tried to show that it is a misunderstanding to treat speech acts in judicial decisions as either an assertive or a declarative. Instead we have differentiate between at least two discussions in a legal process. A discussion between parties and a discussion between the judge and his real or anticipated opponents. In these two discussions the judicial decision plays a different role. In the first he declares something, in the second he asserts something. Finally I have tried to show that the declaration of the judge can be questioned and then be the object of the assertive advancing a standpoint.

NOTES

i. Cf. Hart (1961:142): ‘“The score is what the scorer says it is” would be false if it meant that there was no rule for scoring save what the scorer in his discretion chose to apply. There might indeed be a game with such a rule, and some amusement might be found in playing it if the scorer’s discretion were exercised with some regularity; but it would be a different game. We may call such a game the game of ‘scorer’s discretion’.’

ii. Hart (1961:94) differentiates between primary rules and secondary rules in a legal system. Primary rules are concerned with the actions that individuals must or must not do. Secondary rules are all about primary rules: they specify the ways in which the primary rules may conclusively ascertained, introduced, eliminated, varied and the fact of their violation conclusively determined.

iii. Cf. Austin (1974:14) ‘[…] Our performative, like any other ritual or ceremony, may be, as the lawyers say, ‘nul and void’. If for example, the speaker is not in a position to perform an act of that kind, or if the object with respect to which he purports to perform is not suitable for the purpose, then he doesn’t manage simply by issuing his utterance, to carry out the purported act.’

REFERENCES

Austin, J.L. (1974). Performative-Constative. In: J.R. Searle (Ed.), The Philosophy of Language (pp. 13-22). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Transl. of Austin, J.L. (1962). ‘Performatif-Constatif’. Cahiers de Royaumont, Philosophie IV: La Philosophie analytique. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 271-304.]

Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, Communication and Fallacies. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Feteris, E.T. (1989). Discussieregels in het recht. Een pragma-dialectische analyse van het burgerlijk proces en het strafproces. Dordrecht: Foris.

Hart, H.L.A. (1961). The concept of law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Houtlosser, P. (1994). The Speech act ‘advancing a standpoint’. In: F.H. van Eemeren & R. Grootendorst (eds.), Studies in Pragma-Dialectics (pp. 166-171). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Houtlosser, P. (1995). Standpunten in een kritische discussie. Een pragma-dialectisch perspectief op de identificatie en reconstructie van standpunten. Amsterdam: IFOTT.

Ruiter, D.W.P. (1993). Institutional legal Facts: Legal Powers and their Effects. Dordrecht etc.: Kluwer.

Searle, J.R. (1979). A taxonomy of illocutionary acts. In: J.R. Searle, Expression and Meaning. Studies in the Theory of Speech Acts (p.1-29). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.