ISSA Proceedings 1998 – The Pragma-Dialectics of Visual Argument

1. Introduction A number of recent commentators (among them Birdsell & Groarke 1996, Blair 1996, Groarke 1998, and Shelley 1996) have discussed the role that visual images play in public argument. The present paper is an attempt to sketch a pragma-dialectical account of this role. I will call the argumentation which employs such images “visual argumentation” in order to stress the extent to which the images in question can be compared to verbal claims. Because a detailed account of the pragma-dialectics of visual argument is beyond the scope of a short paper, I will more modestly attempt to sketch some cental features of such an account. In the process I will emphasize two aspects of pragma-dialectics: (i) its commitment tospeech act theory and (ii) the principles of communication it uses to explain implicit and indirect speech acts. I end with some remarks on an approach to visual argumentation which is fundamentally at odds with the one that I propose. 2. Visual Images as Speech Acts Any pragma-dialectical attempt to understand how visual images inform public argument must begin with the recognition that such images can, like verbal claims, function as speech acts in argumentative exchange. Understanding such exchange in a pragma- dialectical way, we can say that argumentation is a reasoned attempt to resolve a dispute, that a dispute centers on a a standpoint which is “entails a certain position in a dispute,” and that an argument is an attempt to defend a standpoint (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, 14). The question whether visual argumentation is possible thus reduces to the question whether visual images can be used to express standpoints and defend them, and can in this way contribute to the critical discussion which revolves around disputes.[i] A comprehensive account of visual images in argumentative contexts requires a detailed account of visual meaning. Because such an account is beyond the scope of the present paper[ii], I will instead demonstrate the possibility of visual argumentation with some select examples. The first is reproduced below. It is a World War I American political cartoon drawn by Luther Bradley and published in the Chicago Daily News. Though the message is in part visual, it functions as a pointed comment on the causes of the war. Ingeniously, Bradley portrays the world at war as a person afflicted with a terrible tooth ache and the world’s “old” monarchies as dental crowns. The nurse labelled “The Spirit of Peace” provides his own diagnosis: the war will end and the world will enjoy peace and comfort only when its old crowns are removed.

1. Introduction A number of recent commentators (among them Birdsell & Groarke 1996, Blair 1996, Groarke 1998, and Shelley 1996) have discussed the role that visual images play in public argument. The present paper is an attempt to sketch a pragma-dialectical account of this role. I will call the argumentation which employs such images “visual argumentation” in order to stress the extent to which the images in question can be compared to verbal claims. Because a detailed account of the pragma-dialectics of visual argument is beyond the scope of a short paper, I will more modestly attempt to sketch some cental features of such an account. In the process I will emphasize two aspects of pragma-dialectics: (i) its commitment tospeech act theory and (ii) the principles of communication it uses to explain implicit and indirect speech acts. I end with some remarks on an approach to visual argumentation which is fundamentally at odds with the one that I propose. 2. Visual Images as Speech Acts Any pragma-dialectical attempt to understand how visual images inform public argument must begin with the recognition that such images can, like verbal claims, function as speech acts in argumentative exchange. Understanding such exchange in a pragma- dialectical way, we can say that argumentation is a reasoned attempt to resolve a dispute, that a dispute centers on a a standpoint which is “entails a certain position in a dispute,” and that an argument is an attempt to defend a standpoint (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, 14). The question whether visual argumentation is possible thus reduces to the question whether visual images can be used to express standpoints and defend them, and can in this way contribute to the critical discussion which revolves around disputes.[i] A comprehensive account of visual images in argumentative contexts requires a detailed account of visual meaning. Because such an account is beyond the scope of the present paper[ii], I will instead demonstrate the possibility of visual argumentation with some select examples. The first is reproduced below. It is a World War I American political cartoon drawn by Luther Bradley and published in the Chicago Daily News. Though the message is in part visual, it functions as a pointed comment on the causes of the war. Ingeniously, Bradley portrays the world at war as a person afflicted with a terrible tooth ache and the world’s “old” monarchies as dental crowns. The nurse labelled “The Spirit of Peace” provides his own diagnosis: the war will end and the world will enjoy peace and comfort only when its old crowns are removed.

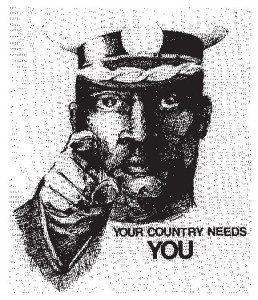

Press has described the view of international politics which characterizes this and other American cartoons of the same period in his book, The Political Cartoon. “War is,” it holds, “made necessary by the machinations of corrupt and archaic feudal monarchs. Such outmoded feudal leaders seek war because they glory in the pomp of military splendour and aggrandizement, or else they are prone to excesses and saber rattling that inadvertently leads to war. The root cause of war is thus… feudal monarchs and self-proclaimed Emperors [who] vie with each other for the spoils of empire, in a manner suited to the Middle Ages or to Graustark or Zenda, but not to modern times. The solution to war is to replace an outdated feudalism…” (Press 1981, 158). In presenting the standpoint this implies, Bradley’s cartoon functions as a speech act which may appropriately be called an “assertive.” The proposition it asserts might be summarized as the claim that “If the world is to enjoy peace, then old monarchies must be removed.” In the present context, it illustrates the point that a visual image may present a standpoint and in this way initiate or contribute to critical discussion. As in the case of standpoints expressed in purely verbal ways, one might agree with Bradley’s position and adduce evidence in support of it. Alternatively, one might – like Press – argue that it is founded on the simple minded view that American democracy is a panacea which can, if propagated, solve the world’s problems. The important point is that Bradley’s standpoint can thus become the locus of argumentative exchange. Bradley’s cartoon might usefully be described as a sophisticated visual metaphor. His standpoint might therefore be said to express the view that “The world is (like) a person with a bad tooth ache who needs old crowns (monarchies) removed.” Not all visual images can be classed as metaphors, but the role that visual and verbal metaphors play in critical discussion makes the important point that standpoints are often expressed in ways that extend beyond literally intended verbal claims. The study of visual argumentation in this way extends argumentation theory beyond this narrow compass. But critical discussion implies something more than the expression of a standpoint. It is, therefore, important to see that visual images can occupy other argumentative roles. Most significantly, they can incorporate attempts to justify a standpoint and can in this way function as arguments, not only in a pragma-dialectical sense, but also in the traditional sense which implies premises and a conclusion. The nature of visual images can be illustrated with another Luther Bradley cartoon, this one from September 15, 1914, shortly after World War I began (below). In this case, the cartoon presents war as a run away automobile speeding down a slope. The driver, EUROPE, sits beside the car’s “self-starter,” looking in dismay for its “self-stopper.” Much to her chagrin, it turns out that war is not equipped with one. The message might be summarized as follows.  (Standpoint/Conclusion:) Europe is naive and foolish beginning a war for (Premise:) it should know that war is not easily stopped and is bound to end – like Bradley’s runaway automobile – in ultimate disaster. The sign beside the car that points ahead to “Bankruptcy” clearly tells us that there will be an economic side to this disaster. So understood, Bradley’s cartoon expresses a standpoint but also provides grounds for believing that it is true. It can, therefore, be understood as a visual argument. Once we recognize Bradley’s second cartoon as a visual argument, we can analyze it in much the way that we analyze verbal arguments. It is in this regard significant that the argument has close affinities to slippery slope arguments, for they also argue against some action by suggesting that it will initiate a chain of consequences which will have some undesirable result. It might be added that the argument is founded on a generalization about war which is applied to a particular war. The argument is in this way comparable to many verbal appeals to general and universal statements. Many other examples of visual argumentation can easily be found in other political cartoons, in visual art, in magazine and television advertising, and in political campaigns of all sorts. The prevalence of such argument well establishes it as an important species of reasoning which needs to be recognized by any comprehensive theory of argumentation. In the case of pragma-dialectics, the first step in this direction must be a more explicit recognition of the role that speech acts often play in critical discussion, especially in the public sphere. This said, something more is required if visual arguments are to be fully integrated into a pragma-dialectical account of argument. This “something more” can be achieved by turning to the pragma-dialectical account of implicit and indirect speech acts, for it readily explains the way in which visual images function as contributions to argumentative exchange. It is here that pragma-dialectics has the most to offer to our understanding of visual argument, for its account of the principles of communication provides a ready explanation of the mechanics of visual argumentation and the indirect arguments that makes it possible. 3. Visual Images as Implicit and Indirect Speech Acts Often, the possibility of visual argumentation has been overlooked because the visual images which function as argumentative speech acts are best classified as implicit and indirect. It would be a mistake to conclude that visual argumentation is necessarily vague and imprecise. Visual images are often explicit in the sense that there meaning is clear and unambiguous. Our first examples are a case in point. Visual images are necessarily implicit and indirect only in the sense that they are not explicitly verrbal and must, therefore, be made verbally explicit when we pursue argument analysis. In many ways, the suggestion that argumentative visual images function as indirect speech acts is very much in keeping with a pragma-dialectical point of view, for it holds that “[i]n practice, the explicit performance of a speech act is the exception rather than the rule” (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, 44). If we extend its account of other implicit and indirect speech acts to the visual realm, then we must give argumentation visuals a “maximally argumentative interpretation,” in order to ensure that their argumentative function is fully recognized. In doing so, we can apply the “principles of communication” that govern all speech acts (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, 49-55). They can be summarized by stipulating that speech acts should not be (i) incomprehensible, (ii) insincere, (iii) superfluous, (iv) futile, or (v) inappropriately connected to other speech acts. The extent to which the principles of communication can be usefully applied to visual images warrants special comment. Consider the cartoon I have reproduced below. Because I want to stress the wide applicability of the principles of communication in the visual realm, I have in this case picked an image which is not an example of visual argumentation. Instead, it functions as a simple joke. Significantly, it is a joke which is founded on a visual contradiction. Its punch line is found in the last frame, which visually contradicts the earlier frames, which portray the runner running and winning a race. We instinctively avoid this contradiction by interpreting the sequence of visuals in the comic strip in a way that adheres to the principles of communication and avoids the conclusion that they are incomprehensible, superfluous, etc. We do so by interpreting the runner in the different frames as the same runner, and by interpreting the first four frames as an account of his imagination. The joke occurs because his athletic prowess and accomplishments are, in no uncertain terms, revealed to be a figment of his imagination when he crashes to the floor in the final drawing. No verbal or visual cues are needed to guarantee this interpretation because it is instinctively established by our commitment to the principles of communication. Similar appeals to the principles of communication explain how we understand many images that occur in critical discussion. In the present paper, I want to illustrate this point with two examples. The first is the following 1997 recruitment poster for the British Army (reported in The Guardian Weekly, Vol. 157, No. 16, Oct. 19, p. 9). It is a remake of a famous World War I recruitment poster which featured Lord Kitchener pointing his gloved hand at the viewer declaring “Your country needs YOU.” In due course the poster became a patriotic symbol. In the 1997 version it is altered by replacing Lord Kitchener’s face with the face of a black officer. Looked at from the point of view of the principles of communication, the purposeful disruption of the traditional image calls for an interpretation of the poster which does renders this disruption meaningful and significant. We can begin to construct a plausible interpretation by noting that the 1914 poster which is the basis of the 1997 remake is readily understood as a visual argument which attempts to convince potential recruits that “(Conclusion/Standpoint:) You should join the army because (Premise:) Your country needs you.” One might include as an implicit premise or assumption the patriotic principle that you should do what your country needs you to do.

(Standpoint/Conclusion:) Europe is naive and foolish beginning a war for (Premise:) it should know that war is not easily stopped and is bound to end – like Bradley’s runaway automobile – in ultimate disaster. The sign beside the car that points ahead to “Bankruptcy” clearly tells us that there will be an economic side to this disaster. So understood, Bradley’s cartoon expresses a standpoint but also provides grounds for believing that it is true. It can, therefore, be understood as a visual argument. Once we recognize Bradley’s second cartoon as a visual argument, we can analyze it in much the way that we analyze verbal arguments. It is in this regard significant that the argument has close affinities to slippery slope arguments, for they also argue against some action by suggesting that it will initiate a chain of consequences which will have some undesirable result. It might be added that the argument is founded on a generalization about war which is applied to a particular war. The argument is in this way comparable to many verbal appeals to general and universal statements. Many other examples of visual argumentation can easily be found in other political cartoons, in visual art, in magazine and television advertising, and in political campaigns of all sorts. The prevalence of such argument well establishes it as an important species of reasoning which needs to be recognized by any comprehensive theory of argumentation. In the case of pragma-dialectics, the first step in this direction must be a more explicit recognition of the role that speech acts often play in critical discussion, especially in the public sphere. This said, something more is required if visual arguments are to be fully integrated into a pragma-dialectical account of argument. This “something more” can be achieved by turning to the pragma-dialectical account of implicit and indirect speech acts, for it readily explains the way in which visual images function as contributions to argumentative exchange. It is here that pragma-dialectics has the most to offer to our understanding of visual argument, for its account of the principles of communication provides a ready explanation of the mechanics of visual argumentation and the indirect arguments that makes it possible. 3. Visual Images as Implicit and Indirect Speech Acts Often, the possibility of visual argumentation has been overlooked because the visual images which function as argumentative speech acts are best classified as implicit and indirect. It would be a mistake to conclude that visual argumentation is necessarily vague and imprecise. Visual images are often explicit in the sense that there meaning is clear and unambiguous. Our first examples are a case in point. Visual images are necessarily implicit and indirect only in the sense that they are not explicitly verrbal and must, therefore, be made verbally explicit when we pursue argument analysis. In many ways, the suggestion that argumentative visual images function as indirect speech acts is very much in keeping with a pragma-dialectical point of view, for it holds that “[i]n practice, the explicit performance of a speech act is the exception rather than the rule” (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, 44). If we extend its account of other implicit and indirect speech acts to the visual realm, then we must give argumentation visuals a “maximally argumentative interpretation,” in order to ensure that their argumentative function is fully recognized. In doing so, we can apply the “principles of communication” that govern all speech acts (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, 49-55). They can be summarized by stipulating that speech acts should not be (i) incomprehensible, (ii) insincere, (iii) superfluous, (iv) futile, or (v) inappropriately connected to other speech acts. The extent to which the principles of communication can be usefully applied to visual images warrants special comment. Consider the cartoon I have reproduced below. Because I want to stress the wide applicability of the principles of communication in the visual realm, I have in this case picked an image which is not an example of visual argumentation. Instead, it functions as a simple joke. Significantly, it is a joke which is founded on a visual contradiction. Its punch line is found in the last frame, which visually contradicts the earlier frames, which portray the runner running and winning a race. We instinctively avoid this contradiction by interpreting the sequence of visuals in the comic strip in a way that adheres to the principles of communication and avoids the conclusion that they are incomprehensible, superfluous, etc. We do so by interpreting the runner in the different frames as the same runner, and by interpreting the first four frames as an account of his imagination. The joke occurs because his athletic prowess and accomplishments are, in no uncertain terms, revealed to be a figment of his imagination when he crashes to the floor in the final drawing. No verbal or visual cues are needed to guarantee this interpretation because it is instinctively established by our commitment to the principles of communication. Similar appeals to the principles of communication explain how we understand many images that occur in critical discussion. In the present paper, I want to illustrate this point with two examples. The first is the following 1997 recruitment poster for the British Army (reported in The Guardian Weekly, Vol. 157, No. 16, Oct. 19, p. 9). It is a remake of a famous World War I recruitment poster which featured Lord Kitchener pointing his gloved hand at the viewer declaring “Your country needs YOU.” In due course the poster became a patriotic symbol. In the 1997 version it is altered by replacing Lord Kitchener’s face with the face of a black officer. Looked at from the point of view of the principles of communication, the purposeful disruption of the traditional image calls for an interpretation of the poster which does renders this disruption meaningful and significant. We can begin to construct a plausible interpretation by noting that the 1914 poster which is the basis of the 1997 remake is readily understood as a visual argument which attempts to convince potential recruits that “(Conclusion/Standpoint:) You should join the army because (Premise:) Your country needs you.” One might include as an implicit premise or assumption the patriotic principle that you should do what your country needs you to do.  The 1997 version of the poster presents a similar argument, but with a new twist which overshadows the original meaning. Clearly, the poster is an attempt to “reach out” to ethnic minorities which are now explicitly recognized by the poster, even though they do not fit the traditional image of the white anglo saxon British soldier. This change in the image has two significant consequences for its meaning. First, it directs the original argument of the poster to a particular audience, i.e. ethnic minorities. Second, and perhaps more significantly, it attempts to convince this audience that the British Army is committed to ethnic diversity. We might therefore summarize the 1997 argument as follows. Premise 1: Your country needs you. Implicit Premise 2: You should do what your country needs. Premise 3: The army is committed to ethnic diversity. Standpoint/Conclusion: You (i.e. members of ethnic minorities) should join the British Army. It is in passing worth noting that this is a case in which the existence of the visual image in an argument is itself offered as evidence for its conclusion. A second example which can illustrate the way in which the principles of communication allow the interpretation of visual argumentation is a recent advertisement for Bacardi Rum. Under the title “Just add Bacardi” it features a huge bottle of Bacardi which is being emptied on a sleepy little village. In a different light and from a different angle, the village scene could be a charming rustic landscape scene, but the time of day (dusk), the lack of activity, and the lonely lights in the windows now suggest a boring hamlet where there is nothing to do. The lack of activity contrasts sharply with the image which appears where the Bacardi splashes onto the scene below. Like a miracle fertilizer, it produces a bustling Manhattan-like cityscape complete with skyscrapers, lights, nightclubs, glitzy restaurants and a thriving night life. Taken as a whole, the advertisement contrasts this exciting scene with the sleepy village which surrounds it. The message is obvious: “If you drink Bacardi, your sleepy life will be transformed into something as exciting as downtown Manhattan.” As this suggestion is offered as a reason for believing that “You should buy Bacardi Rum,” this is another good example of a visual argument. Significantly, this is a visual argument which seems guilty of the fallacy affirming the consequent, for it argues that you will have an exciting night life if you drink Bacardi, implicitly assumes that you want an exciting night life and concludes that you should drink Bacardi. In the present context, it is enough to note that the meaning is clear, even though any attempt to understand the picture literally entails a series of absurdities – bottles of Bacardi are not so absurdly huge, they do not pour their contents onto sleepy unexpecting villages and if they did the result would be sticky streets and dead plants rather than a Manhattan streetscape. Looked at literally the image is therefore incongruous. We nonetheless manage to easily understand it because we automatically assume the principles of communication, which require that we find some plausible way to make the visual images coherently tied to one another in a way that produces a plausible meaning. We succeed by interpreting the image as a metaphor which is not intended literally. We use the principles of communication in a similar way when we interpret verbal metaphors. We do not, therefore, have problems understanding the verbal claim that “Jackie is a block of ice” and do not interpret it to mean that her temperature is zero degrees celsius, she turns into liquid at room temperature, is composed of nothing but water and so on. Drastic misunderstandings of this sort are as infrequent in the visual as the verbal sphere, because in both cases the principles of communication undermine them. 4. Two Approaches to Visual Argument Because the role that visual images play in public argument can be explained in the way I have suggested, pragma-dialectics provides a relatively simple way to assess and evaluate visual argumentation. In the present context, it is enough to say that the account I have proposed suggests that it can assess visual argumentation in essentially the same way in which it assesses other instances of indirect argument. While I will not pursue this point, it is one of the strengths of the proposed approach, for it allows us to assess visual argumentation as fallacious, valid, sound, etc. without requiring that we devise a new theory of argument which is restricted to the visual realm. One might therefore contrast my approach to visual argumentation with attempts to formulate a theory of visual argument which treats it and verbal argument as irreconcilably distinct. One approach to non-verbal arguments which tends in this direction is found in Gilbert 1997, but I will in this paper focus on the account of advertising found in Johnson and Blair 1994. In the present context advertising is significant because it tends to emphasize visual components and is in this way heavily committed to visual argument. Given this feature, one might expect an attempt to come to grips with advertising to result in an expansion of the standard account of argumentation which allows it to encompasses visual statements and arguments, in a manner analogous to the expansion of pragma-dialectics I have suggested here. Instead, Johnson and Blair argue that advertising only “mimics argumentation,” that its argumentative leanings are a “facade,” and that “most advertising works not at the rational level but at a deeper level” which implies a fundamental difference between its “logic” and “the logic of real arguments” (Johnson and Blair 1994, 220-221). One might summarize their view by saying that it treats advertising as a form of persuasion which is distinct from argument. It in this way suggests that the visual images that proliferate in advertising should be seen as instances of persuasion, and not in the manner I have proposed – as instances of argument. In many ways, Johnson and Blair’s account of advertising is impressive and insightful. It convincingly makes the point that advertising is characterized by many sophistic ploys, and is firmly built upon a self-interested attempt to understand what motivates human action. Granting all these points, one might take their comparison of advertising and ancient sophism in the direction I have already proposed. For though one might criticize the sophists for their slippery tactics, it is clear that they saw themselves as experts in argumentation, and not as individuals who gave up argument for some other form of persuasion. Protagoras’ famous claim is, therefore, the claim that he can make the weaker argument (logos) the stronger. In view of this, one might compare advertisers to sophists without concluding that they exchange argument for persuasion. Such a view is more in keeping with the pragma-dialectical approach I have developed here, for it proposes a “maximally argumentative” interpretation of the visual images which are employed in advertising contexts, and this implies an emphasis on the attempt to interpret a visual as an explicit argument or the expression of a standpoint which calls for one.

The 1997 version of the poster presents a similar argument, but with a new twist which overshadows the original meaning. Clearly, the poster is an attempt to “reach out” to ethnic minorities which are now explicitly recognized by the poster, even though they do not fit the traditional image of the white anglo saxon British soldier. This change in the image has two significant consequences for its meaning. First, it directs the original argument of the poster to a particular audience, i.e. ethnic minorities. Second, and perhaps more significantly, it attempts to convince this audience that the British Army is committed to ethnic diversity. We might therefore summarize the 1997 argument as follows. Premise 1: Your country needs you. Implicit Premise 2: You should do what your country needs. Premise 3: The army is committed to ethnic diversity. Standpoint/Conclusion: You (i.e. members of ethnic minorities) should join the British Army. It is in passing worth noting that this is a case in which the existence of the visual image in an argument is itself offered as evidence for its conclusion. A second example which can illustrate the way in which the principles of communication allow the interpretation of visual argumentation is a recent advertisement for Bacardi Rum. Under the title “Just add Bacardi” it features a huge bottle of Bacardi which is being emptied on a sleepy little village. In a different light and from a different angle, the village scene could be a charming rustic landscape scene, but the time of day (dusk), the lack of activity, and the lonely lights in the windows now suggest a boring hamlet where there is nothing to do. The lack of activity contrasts sharply with the image which appears where the Bacardi splashes onto the scene below. Like a miracle fertilizer, it produces a bustling Manhattan-like cityscape complete with skyscrapers, lights, nightclubs, glitzy restaurants and a thriving night life. Taken as a whole, the advertisement contrasts this exciting scene with the sleepy village which surrounds it. The message is obvious: “If you drink Bacardi, your sleepy life will be transformed into something as exciting as downtown Manhattan.” As this suggestion is offered as a reason for believing that “You should buy Bacardi Rum,” this is another good example of a visual argument. Significantly, this is a visual argument which seems guilty of the fallacy affirming the consequent, for it argues that you will have an exciting night life if you drink Bacardi, implicitly assumes that you want an exciting night life and concludes that you should drink Bacardi. In the present context, it is enough to note that the meaning is clear, even though any attempt to understand the picture literally entails a series of absurdities – bottles of Bacardi are not so absurdly huge, they do not pour their contents onto sleepy unexpecting villages and if they did the result would be sticky streets and dead plants rather than a Manhattan streetscape. Looked at literally the image is therefore incongruous. We nonetheless manage to easily understand it because we automatically assume the principles of communication, which require that we find some plausible way to make the visual images coherently tied to one another in a way that produces a plausible meaning. We succeed by interpreting the image as a metaphor which is not intended literally. We use the principles of communication in a similar way when we interpret verbal metaphors. We do not, therefore, have problems understanding the verbal claim that “Jackie is a block of ice” and do not interpret it to mean that her temperature is zero degrees celsius, she turns into liquid at room temperature, is composed of nothing but water and so on. Drastic misunderstandings of this sort are as infrequent in the visual as the verbal sphere, because in both cases the principles of communication undermine them. 4. Two Approaches to Visual Argument Because the role that visual images play in public argument can be explained in the way I have suggested, pragma-dialectics provides a relatively simple way to assess and evaluate visual argumentation. In the present context, it is enough to say that the account I have proposed suggests that it can assess visual argumentation in essentially the same way in which it assesses other instances of indirect argument. While I will not pursue this point, it is one of the strengths of the proposed approach, for it allows us to assess visual argumentation as fallacious, valid, sound, etc. without requiring that we devise a new theory of argument which is restricted to the visual realm. One might therefore contrast my approach to visual argumentation with attempts to formulate a theory of visual argument which treats it and verbal argument as irreconcilably distinct. One approach to non-verbal arguments which tends in this direction is found in Gilbert 1997, but I will in this paper focus on the account of advertising found in Johnson and Blair 1994. In the present context advertising is significant because it tends to emphasize visual components and is in this way heavily committed to visual argument. Given this feature, one might expect an attempt to come to grips with advertising to result in an expansion of the standard account of argumentation which allows it to encompasses visual statements and arguments, in a manner analogous to the expansion of pragma-dialectics I have suggested here. Instead, Johnson and Blair argue that advertising only “mimics argumentation,” that its argumentative leanings are a “facade,” and that “most advertising works not at the rational level but at a deeper level” which implies a fundamental difference between its “logic” and “the logic of real arguments” (Johnson and Blair 1994, 220-221). One might summarize their view by saying that it treats advertising as a form of persuasion which is distinct from argument. It in this way suggests that the visual images that proliferate in advertising should be seen as instances of persuasion, and not in the manner I have proposed – as instances of argument. In many ways, Johnson and Blair’s account of advertising is impressive and insightful. It convincingly makes the point that advertising is characterized by many sophistic ploys, and is firmly built upon a self-interested attempt to understand what motivates human action. Granting all these points, one might take their comparison of advertising and ancient sophism in the direction I have already proposed. For though one might criticize the sophists for their slippery tactics, it is clear that they saw themselves as experts in argumentation, and not as individuals who gave up argument for some other form of persuasion. Protagoras’ famous claim is, therefore, the claim that he can make the weaker argument (logos) the stronger. In view of this, one might compare advertisers to sophists without concluding that they exchange argument for persuasion. Such a view is more in keeping with the pragma-dialectical approach I have developed here, for it proposes a “maximally argumentative” interpretation of the visual images which are employed in advertising contexts, and this implies an emphasis on the attempt to interpret a visual as an explicit argument or the expression of a standpoint which calls for one.  It does not follow that the criticisms of advertisements which Johnson and Blair make no longer apply, but that they must frequently be applied to attempts to argue rather than persuade. Suppressed evidence is not, for example, less problematic (and perhaps more problematic) when one describes a visual advertisement as an attempt to argue for the conclusion that one should buy a certain product. The illegitimate appeals to pity, fear and other emotions which Johnson and Blair identify as a key ingredient of advertising remain similarly problematic even when advertising is understood as a form of argumentative appeal. Looked at from this point of view, it might seem that my approach and the approach to visuals implicit in Johnson and Blair are equal, for either can explain the problems with the images that characterize contemporary advertising. To some extent this is true, though I believe that there are four problems with the attempt to drive a wedge between argument and advertising and, more specifically, argument and advertising visuals. I will end this paper by proposing them as four reasons which favour a theoretical approach to visual argumentation which construes it as an extension of verbal arguments rather than a species of persuasion which abides by a different ‘logic.’ One problem with the attempt to treat advertising visuals as persuasion rather than argument arises in the context of the sophistic features of the former which motivate this view. Here the problem is that these aspects of advertising have clear analogues in verbal argumentation. Purposeful ambiguity and vagueness, slippery allusions, the suppression of evidence, and self-serving appeals to fears, pity and other emotions are not, for example, the sole preserve of advertising and their visuals. They are, on the contrary, a constant feature of verbal critical discussion, especially in the public sphere. So long as their existence there does not show that verbal argumentation of this sort needs to be classified as persuasion rather than argument, it is difficult to see why it should entail this conclusion in the case of advertising images. It is precisely because there is this kind of overlap that it is useful to apply pragma-dialectical accounts of fallacies to visual argumentation. In marked contrast, the attempt to divorce visual and verbal arguments seems to unnecessarily separate two kinds of arguments which may be more efficiently understood in terms of a unified theory of argument. A second problem with the attempt to treat visual advertising images as instances of mere persuasion arises in cases in which they do not seem to be sophistical, even if they are problematic. Here the problem is that many instances of visual argument seem to clearly conform to standard forms of argument. A Canadian television advertisement for Cooper hockey equipment features players from the National Hockey League using and recommending Cooper equipment. Though the appeal was primarily visual this seems a clear case of argument by authority. The same can be said of many other advertisements which are similarly constructed around some alleged expertise. When a man with horn rimmed glasses, a white lab coat, and a stethoscope tells us that this pain killer relieves headaches faster than that one, we know that he is being presented as a medical expert. Because visual appeals to authority of this sort demand the same kind of analysis as verbal appeals to authority – an analysis which asks whether the authority’s credentials have been properly presented, whether he or she is an appropriate authority in the case in question, whether they have a vested interest in a particular conclusion, etc. – it seems a mistake to treat them as anything other than arguments in the traditional sense. One might respond to such examples by trying to distinguish between visual images which function as arguments and those which function only as persuasion. But this requires some principle of division which can clearly distinguish these two sets of images. I propose this as a third problem for the persuasion account, for it is not clear what principles can be employed in this regard. In contrast, the interpretation strategy which I have gleaned from pragma-dialectics – which proposes that we interpret argumentative visuals in a maximally argumentative way – establishes clear priorities which are relatively easy to implement in the practice of argument analysis. A fourth and final problem with the kind of approach proposed by Johnson and Blair is its emphasis on the negative aspects of advertising and the visuals it employs. This is in many ways in keeping with their emphasis on fallacies, which teach argumentation skills by identifying the mistakes that frequently occur in ordinary argumentation. A number of commentators have criticized this approach on the grounds that it emphasizes instances of poor rather than good reasoning (see, for example, Hitchcock 1995 and Tindale 1997). In their own discussion of advertising, Johnson and Blair themselves point out that it is a mistake to dismiss all advertisements as deceptive and misleading, but their decision to treat them as attempts at persuasion which only mimic arguments still has a very negative slant and invites this conclusion, especially in students. It is in this regard worth noting that the persuasion approach to visual argumentation supports a common prejudice against the visual which has tended to characterize argumentation theory. In view of this prejudice, it is all the more important that we emphasize the possibility of good visual argumentation. In some ways and in some contexts, I would argue that visual argumentation is actually preferable to verbal argument. If one wishes to argue about the horrors of war or the desperate plight of children in the developing world, for example, then it is arguable that it is not visual images but words which tend to be inadequate conveyers of important truths. If this is right, then there are practical contexts in which visual argumentation is more appropriate than its verbal analogue. A more detailed discussion of visual argumentation lies beyond the scope of the present paper. In the present circumstances, I hope I have given some reasons for believing both that we should accept the possibility of visual argumentation, and that pragma-dialectics can provide a basis for an understanding of its content. NOTES i. The most-cited study here is by Tversky and Kahneman. They conducted an experiment in which a witness’ testimony had to be combined with knowledge of prior probability to yield a value for claim probability – a simpler situation than the one being discussed here. Their subjects were told the following story. A cab was involved in a hit and run accident at night. Two cab companies, the Green and the Blue, operate in the city. You are given the following data: (a) 85% of the cabs in the city are Green and 15% are Blue, (b) a witness identified the cab as Blue. The court tested the reliability of the witness under the same circumstances that existed on the night of the accident and concluded that the witness correctly identified each one of the two colors 80% of the time and failed 20% of the time. What is the probability that the cab involved in the accident was Blue rather than Green?” (From Baron, J., Thinking and Deciding, 1988, p.205) Most subjects gave estimates near 80%, as if ignoring the base rate for Blue cabs, which is 15%. The Bayes Theorem shows that the correct answer is 41%! Using the procedure advocated in this paper, we would not accept the eyewitness claim that it was a Blue cab. To warrant accepting the claim, the witness’ error rate would have to be less than 1/4 (we are dealing with a claim, not an argument) x 0.15 (the initial probability that a cab would be a Blue cab), or 0.04. But it is actually 0.20. ii. In part because visual images may gain meaning in such a great variety of ways (by convention, by demonstration, by purposeful exaggeration, and so on). REFERENCES Birdsell, D & L. Groarke (1996). “Toward A Theory of Visual Argument.” Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 1-10. Blair, J.A. (1996). “The Possibility and Actuality of Visual Argument.” Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 23-39. Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, Communication and Fallacies. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Gilbert, M. (1997). Coalescent Argument. Mahweh: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Groarke, L. (1998). “Logic, Art and Argument.” Informal Logic forthcoming. Hitchcock, D. “Do the Fallacies Have a Place in the Teaching of Reasoning Skills or Critical Thinking?” In: H.V. Hansen & R.C. Pinto, Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995. Johnson, R.H. & J.A. Blair (1994). Logical Self-Defense. United States Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 1994. Press, C. (1981). The Political Cartoon. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. Shelley, C. “Rhetorical and Demonstrative Modes of Visual Argument: Looking at Images of Human Evolution.” Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 53-68. Tindale, C. (1997). “The Negative Approach to Teaching Argument: The Case Against Applied Fallacy Theory,” Presented at the Second International Conference on Teaching and Learning Argument. Middlesex University, London.

It does not follow that the criticisms of advertisements which Johnson and Blair make no longer apply, but that they must frequently be applied to attempts to argue rather than persuade. Suppressed evidence is not, for example, less problematic (and perhaps more problematic) when one describes a visual advertisement as an attempt to argue for the conclusion that one should buy a certain product. The illegitimate appeals to pity, fear and other emotions which Johnson and Blair identify as a key ingredient of advertising remain similarly problematic even when advertising is understood as a form of argumentative appeal. Looked at from this point of view, it might seem that my approach and the approach to visuals implicit in Johnson and Blair are equal, for either can explain the problems with the images that characterize contemporary advertising. To some extent this is true, though I believe that there are four problems with the attempt to drive a wedge between argument and advertising and, more specifically, argument and advertising visuals. I will end this paper by proposing them as four reasons which favour a theoretical approach to visual argumentation which construes it as an extension of verbal arguments rather than a species of persuasion which abides by a different ‘logic.’ One problem with the attempt to treat advertising visuals as persuasion rather than argument arises in the context of the sophistic features of the former which motivate this view. Here the problem is that these aspects of advertising have clear analogues in verbal argumentation. Purposeful ambiguity and vagueness, slippery allusions, the suppression of evidence, and self-serving appeals to fears, pity and other emotions are not, for example, the sole preserve of advertising and their visuals. They are, on the contrary, a constant feature of verbal critical discussion, especially in the public sphere. So long as their existence there does not show that verbal argumentation of this sort needs to be classified as persuasion rather than argument, it is difficult to see why it should entail this conclusion in the case of advertising images. It is precisely because there is this kind of overlap that it is useful to apply pragma-dialectical accounts of fallacies to visual argumentation. In marked contrast, the attempt to divorce visual and verbal arguments seems to unnecessarily separate two kinds of arguments which may be more efficiently understood in terms of a unified theory of argument. A second problem with the attempt to treat visual advertising images as instances of mere persuasion arises in cases in which they do not seem to be sophistical, even if they are problematic. Here the problem is that many instances of visual argument seem to clearly conform to standard forms of argument. A Canadian television advertisement for Cooper hockey equipment features players from the National Hockey League using and recommending Cooper equipment. Though the appeal was primarily visual this seems a clear case of argument by authority. The same can be said of many other advertisements which are similarly constructed around some alleged expertise. When a man with horn rimmed glasses, a white lab coat, and a stethoscope tells us that this pain killer relieves headaches faster than that one, we know that he is being presented as a medical expert. Because visual appeals to authority of this sort demand the same kind of analysis as verbal appeals to authority – an analysis which asks whether the authority’s credentials have been properly presented, whether he or she is an appropriate authority in the case in question, whether they have a vested interest in a particular conclusion, etc. – it seems a mistake to treat them as anything other than arguments in the traditional sense. One might respond to such examples by trying to distinguish between visual images which function as arguments and those which function only as persuasion. But this requires some principle of division which can clearly distinguish these two sets of images. I propose this as a third problem for the persuasion account, for it is not clear what principles can be employed in this regard. In contrast, the interpretation strategy which I have gleaned from pragma-dialectics – which proposes that we interpret argumentative visuals in a maximally argumentative way – establishes clear priorities which are relatively easy to implement in the practice of argument analysis. A fourth and final problem with the kind of approach proposed by Johnson and Blair is its emphasis on the negative aspects of advertising and the visuals it employs. This is in many ways in keeping with their emphasis on fallacies, which teach argumentation skills by identifying the mistakes that frequently occur in ordinary argumentation. A number of commentators have criticized this approach on the grounds that it emphasizes instances of poor rather than good reasoning (see, for example, Hitchcock 1995 and Tindale 1997). In their own discussion of advertising, Johnson and Blair themselves point out that it is a mistake to dismiss all advertisements as deceptive and misleading, but their decision to treat them as attempts at persuasion which only mimic arguments still has a very negative slant and invites this conclusion, especially in students. It is in this regard worth noting that the persuasion approach to visual argumentation supports a common prejudice against the visual which has tended to characterize argumentation theory. In view of this prejudice, it is all the more important that we emphasize the possibility of good visual argumentation. In some ways and in some contexts, I would argue that visual argumentation is actually preferable to verbal argument. If one wishes to argue about the horrors of war or the desperate plight of children in the developing world, for example, then it is arguable that it is not visual images but words which tend to be inadequate conveyers of important truths. If this is right, then there are practical contexts in which visual argumentation is more appropriate than its verbal analogue. A more detailed discussion of visual argumentation lies beyond the scope of the present paper. In the present circumstances, I hope I have given some reasons for believing both that we should accept the possibility of visual argumentation, and that pragma-dialectics can provide a basis for an understanding of its content. NOTES i. The most-cited study here is by Tversky and Kahneman. They conducted an experiment in which a witness’ testimony had to be combined with knowledge of prior probability to yield a value for claim probability – a simpler situation than the one being discussed here. Their subjects were told the following story. A cab was involved in a hit and run accident at night. Two cab companies, the Green and the Blue, operate in the city. You are given the following data: (a) 85% of the cabs in the city are Green and 15% are Blue, (b) a witness identified the cab as Blue. The court tested the reliability of the witness under the same circumstances that existed on the night of the accident and concluded that the witness correctly identified each one of the two colors 80% of the time and failed 20% of the time. What is the probability that the cab involved in the accident was Blue rather than Green?” (From Baron, J., Thinking and Deciding, 1988, p.205) Most subjects gave estimates near 80%, as if ignoring the base rate for Blue cabs, which is 15%. The Bayes Theorem shows that the correct answer is 41%! Using the procedure advocated in this paper, we would not accept the eyewitness claim that it was a Blue cab. To warrant accepting the claim, the witness’ error rate would have to be less than 1/4 (we are dealing with a claim, not an argument) x 0.15 (the initial probability that a cab would be a Blue cab), or 0.04. But it is actually 0.20. ii. In part because visual images may gain meaning in such a great variety of ways (by convention, by demonstration, by purposeful exaggeration, and so on). REFERENCES Birdsell, D & L. Groarke (1996). “Toward A Theory of Visual Argument.” Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 1-10. Blair, J.A. (1996). “The Possibility and Actuality of Visual Argument.” Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 23-39. Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, Communication and Fallacies. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Gilbert, M. (1997). Coalescent Argument. Mahweh: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Groarke, L. (1998). “Logic, Art and Argument.” Informal Logic forthcoming. Hitchcock, D. “Do the Fallacies Have a Place in the Teaching of Reasoning Skills or Critical Thinking?” In: H.V. Hansen & R.C. Pinto, Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995. Johnson, R.H. & J.A. Blair (1994). Logical Self-Defense. United States Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 1994. Press, C. (1981). The Political Cartoon. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. Shelley, C. “Rhetorical and Demonstrative Modes of Visual Argument: Looking at Images of Human Evolution.” Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 53-68. Tindale, C. (1997). “The Negative Approach to Teaching Argument: The Case Against Applied Fallacy Theory,” Presented at the Second International Conference on Teaching and Learning Argument. Middlesex University, London.