Effective PhD Supervision – Chapter Two – Guidelines for Supervisors

It is well recognised that despite the fact that support for postgraduate students at various levels is available in South Africa, a large and unacceptable proportion of such postgraduate students do not complete their studies. Some of the reasons for this have been ascribed to:

– A lack of understanding by the students and a failure to communicate by the institution as to the standard of work required for a particular degree

– Allocation by the institutions of supervisors who are generally not interested in the topic but are forced to supervise as part of their academic commitments

– Difficulties in conceptualising the programme the student is in and a lack of clear guides – generally replaced by vague requirements

– Differences between supervisors and their approaches to supervision

– Lack of supervisory policy or standards at the departmental, faculty or institutional level

– A general lack of training for supervisors – institutions do not have a formal or informal supervisor training programme

– Time pressures and interruptions placed on supervisors by their institutions, which prevent optimal interaction with postgraduate students

– Poor record-keeping concerning supervision – supervisors do not formalise their interactions with students

– Unclear or the absence of any agreements between supervisors and students and the institution.

Other contributing factors have been identified as poor planning and management (both student and supervisor), vague and unfocused problem formulations, the collection of irrelevant data and inappropriate data analysis. Methodological difficulties may emanate from inadequate knowledge of research methodologies, lack of formal training in research and naive research skills. The inability to formulate scientific arguments, to provide a logical structure, to synthesize and to formulate research problems, and to identify the essence in information and data also influence completion rates. In all of these cases it is tempting to point fingers at students, but the responsibility and the provision of training at all levels must be taken up by the institution.

It is thus important for the supervisor to be acutely aware of factors that may impact on postgraduate studies and supervision. Apart from acquainting oneself with the issues in supervision, it is imperative that supervisors are familiar with the requirements for a PhD degree. Entry requirements, mode of study, academic and discipline-specific demands, holding full or part time jobs, and having family responsibilities are all demanding on the doctoral student. In addition, personal circumstances, integration into a department, and entering a new environment and institutional culture could lead to feelings of loneliness and isolation.

The primary expectation of supervisors by their institutions is familiarisation with all administrative and procedural requirements from registration to final acceptance of the thesis. Each university has its own rules and codes of practice, and supervisors are expected to be familiar with the procedures of their institutions. What follows here are generic suggestions on the operational issues relating to these procedures.

2.2 Procedures and Practices for the Admission and Approval of PhD Degrees

An array of procedures and practices exist and are in place in universities in South African and abroad for the admission and approval of PhD degrees. The process requires approval by a formalised ethics, postgraduate and/or university graduate studies committee with specific individuals indentified to oversee the quality and scholarship of the proposed research project. The kind of structures and committees overseeing this process may differ from university to university, but in essence their task is to ensure the university’s academic integrity and the integrity of the research publications emanating from the research and the development of the individual postgraduate student. Regardless of the institution, it is the responsibility of the department/postgraduate coordinator to ensure that the highest practice is maintained.

2.2.1 Admission requirements for a PhD degree

In general the PhD by research is perceived as the most scholarly/authentic PhD leading to an academic career. However, in keeping with international trends, universities in South Africa are moving towards awarding of the degree based on publications in peer-reviewed journals within a specified time period.

Typically the following admission requirements are applicable to prospective candidates wishing to register for a PhD degree:

- i. a recognised master’s degree, recognised four-year bachelor’s degree, plus at least one year’s registration for an approved master’s degree (in some instances)

- ii. a recognised three-year bachelor’s degree plus at least two years’ registration for an approved master’s degree with submissions of scholarly work in the research area in peer-reviewed journals

- iii. in special circumstances, at the discretion of the Senate, an approved bachelor’s degree or qualification recognised by the Senate as equivalent, as per many universities that recognise prior learning in the area of the research work.

PhD candidates are generally expected to renew their registration annually. It is generally accepted that the duration for the completion of a PhD is five years.

2.2.2 The nature of obtaining a PhD

There are at least two perceptions of how a PhD may be obtained. The first is that the PhD is fundamentally a training in research (an apprenticeship) resulting in small steps forward in the understanding of the subject. The second is that the PhD is a period of scholastic and research endeavour culminating in a major contribution to the understanding of the discipline. The former perception is common in the natural sciences and the latter in the humanities. Clearly individual supervisors’ perceptions will lie at different positions between these perceptions.

It has been normal in many countries for different institutions and different departments to offer a range of structures or routes through to a doctoral degree. Certain levels of attendance may be expected for taught courses, but performance in these courses is not generally assessed. Consideration is now being given to practices which will assess components including taught courses, publication records and work experience.

2.3 Some Considerations for Supervisors

A supervisor may take the following into consideration when assessing the quality of the thesis from the conceptual stage and reflect on the extent to which it adheres to the following criteria:

– Application of conventional research instruments in a new field of investigation

– Combining disparate concepts in new ways to investigate a conventional issue

– Creating different conceptual awareness of existing issues

– Designing and applying existing and new field instruments in a contemporary setting

– Extending the work of others by a variety of methodologies including the use of the original methodology and innovative thinking; identification of new and emerging issues worthy of investigation; and identification of gaps in the existing knowledge and viewing these as challenges

– Demonstration of evidence that the scope and possibilities of the topic were grasped academically

– The thesis provides a systematic account of the research problem, and in formulating specific research questions, demonstrates this

– A conceptual framework has been devised such that the ultimate conclusions can be drawn.

The list is not exhaustive nor does it intend to be prescriptive but may be used as a guide.

Amongst other characteristics used to define a ‘good’ thesis, evidence of the following is generally sought:

– Critical analysis and argument

– Confidence and a rigorous, self-critical approach

– A contribution to knowledge

– Originality, creativity and a degree of risk taking

– Comprehensiveness and scholarly approach

– Appropriate use of methodology with ample evidence of research validity and reliability; presentation and structure of data and thesis; and valid, logical reasoning for the conclusions drawn.

2.3.1 Objectivity and reliability

Objective and reliable (repeatable) findings are clearly more impressive than those which are vague or inconclusive. This poses difficulties in disciplines where the research utilises small sample sizes and is difficult to measure quantitatively. This non-quantitative work is generally recorded and presented in a valid acceptable format. This problem does not exist where the data is quantitative, and where the variables are relatively few and may be identified and measured – as is invariably the case in research in the natural sciences or in quantitative research methodologies.

2.3.2 The significance of a PhD

All universities require doctoral work to be ‘significant’. However, what passes as ‘significant’ depends on the norms of the discipline. It can be argued that knowledge is ‘significant’ for its own sake, irrespective of how useless it may appear to those in other disciplines. In the social sciences and some natural sciences, ‘significance’ is widely regarded as being of help to society in some way and a contribution to knowledge.

2.3.3 Assessing a PhD thesis

Universities appoint a committee of assessors, though its composition differs among institutions. This committee normally nominates three examiners with appropriate skills or expertise in the area in which the research is undertaken. In all instances external examiners are an essential component of the process. The examiners’ reports are considered by the postgraduate committee and the institution for approval. Examiners are expected to recommend the awarding of the degree in accordance with regulations set by each university. (Please refer to the individual institution’s guidelines for such information.)

2.4 Supervisory Practices

2.4.1 Traditional models of supervision

The focus of the traditional model of supervision is usually on the technical aspects of the research, the requirements of the discipline, content knowledge and on the production of a thesis, and can be done by means of:

– Supervision by a single supervisor where one candidate works with a single supervisor on one thesis/dissertation. This model seems to work well in most disciplines. The postgraduate student and supervisor get to know and trust each other; the student feels more comfortable and knows what is expected.

– Supervision by multiple supervisors – where one candidate has two or more supervisors, one supervisor assumes the principle responsibility for supervising the candidate, but is assisted by colleagues with knowledge in other research fields. The group can have several postgraduate students under their supervision.

2.4.2 Workshop model for initiating student awareness

At the beginning of postgraduate study, students usually feel lost and confused. A workshop with other postgraduate students, presented by the academics involved, may provide guidance and training on issues such as the research proposal, academic writing skills, literature searches and reviews, research methodologies, and presentation styles and skills. In this way the postgraduate initiate is brought into the academic environment and may become familiar with various individuals offering specific support. Students would then be expected to have some of the basic skills and could progress to interacting with their supervisors more efficiently.

2.4.3 Directed team

In this model, one individual supervises a small group of students working on related topics or projects, using the same or similar methodology, in the supervisor’s area of expertise. These individuals support each other in collecting material, formulating ideas and maintaining a specific schedule. The supervisor is an expert in the specific field and will be able to focus on the details of each student’s research and work. A methodology group refers to students all using the same methodology, although they may be from different disciplines. The exchange of knowledge and experience in the methodology provides postgraduate students with an in-depth knowledge of the area. This model works well in the early stages of the postgraduate study process when students are still preparing their research proposals. Subsequently, aspects of each piece of work are carved out from the broad data collected and thereafter pursued on an individual basis with the supervisor.

2.4.4 Conference group

Conferences where postgraduate students may present their research findings and share their problems with each other are highly recommended. During such conferences supervisors and students are able to exchange ideas, learn from each other and network. This is particularly useful in national research projects which could develop into significant collaborative research undertakings.

2.5 The Supervisory Process and Tasks

In summary, supervision normally follows a process that includes statement(s) of purpose, research questions, study rationale, literature review, conceptual/theoretical framework, methodology/design, data analysis, validation, significance of the study, limitations of the study, work plan and references. These points are designed to engage the PhD candidate in his/her assessment by asking:

(a) Does the question address a crucial deficiency (silence, contradictions, gap) within the knowledge base on the topic and hold together around that tightly defined topic, and does the question convey intellectual panache?

(b) Does the question hold the potential for broader intellectual import beyond the specific locale of study?

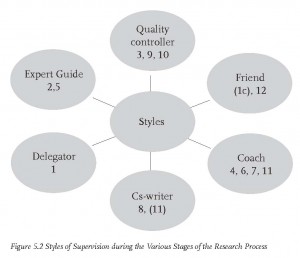

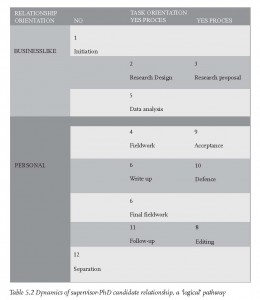

The importance of the initial conceptualisation of the research cannot be stressed enough! Many research projects are set up for failure from the beginning, as not enough intellectual capacity, thought and expertise have been worked through in the initial planning phase. Obviously the styles/models used may differ and there is no one-size-fits-all supervisor. What is presented here are models which may be used independently or collectively vis-à-vis various supervisory opportunities.

2.5.1 Supervision goes beyond the thesis

Effective supervision goes beyond the thesis – it is attending to the broader intellectual development of a PhD candidate. Subsequently, it is important that a supervisor identifies conferences and seminars in which they can present jointly, that they travel together to serious research events, that they write together from an early stage, that they publish together and are always on the lookout for development opportunities that might advance the PhD student, that they inform the student of/direct the student towards the formation of doctoral peer support groups and encourage this formation, and that they identify resources that the student could tap into.

An effective supervisor will always attempt to facilitate connections and network the PhD student to the experts in the field within which he/she has decided to work. Therefore, it is important for the supervisor to introduce the PhD candidate to the leading thinkers in his/her field as much as possible, and to send the best work of the PhD candidate to leading thinkers/scholars who are in the same area of research – thus consciously promoting the PhD student at all times.

2.5.2 Ensuring the PhD candidate becomes independent

Although initially a PhD student depends a lot on his/her supervisor, it is incumbent on the supervisor to attempt to move the student gradually towards greater independence and to know when the candidate is ready to assume more and more responsibility for directing their own work. This implies that the supervisor should avoid making the student a clone of him/herself, but should guide the student towards a topic, theory and method that reflects his/her own ingenuity, desire and voice. It is thus necessary to expose the student, amongst other things, to the work of the supervisor’s opponents or to counter-theories on the work of the supervisor. Therefore, it is always a good idea to encourage the student to critique his/her own work. By doing so, the candidate will get used to the game of scholarly and critical ways of thinking – exactly the attributes one would like to develop within a PhD student.

2.5.3 The importance of effective feedback by the supervisor

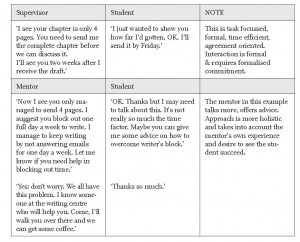

It is desirable that the supervisor’s feedback on written submissions should be direct, fast, clear, honest and consistent. Responsiveness to the students’ work is therefore very important and should include:

– Standardisation of performance for academic delivery

– Feedback on the work’s academic coherence

– Intellectual and relevant advice as to the production of the thesis.

It is suggested that the supervisor keep records of all decisions taken during a contact/feedback session in order to ensure follow-up/continuity of the process until completion/submission (and beyond).

2.5.4 Reflecting on one’s supervisory practice

Feedback on supervision goes some ways towards levelling the playing field in a very hierarchical relationship and assists the supervisor in adjusting his/her strategy to meet the needs of particular students. It furthermore provides the base data for critical scholarship on doctoral supervision. Hard as it may be, supervisors should learn and change their styles based on feedback from their students. It may not be what supervisors wish to hear, but there is a clear benefit and there are always opportunities to do better!

2.6 Sources Consulted

– Lategan, L.O.K. 2008. An introduction to postgraduate supervision. Stellenbosch: Sun Press.

– Pearson, M. 2000. Flexible postgraduate research supervision in an open system. In Kiley, M. And Mullins, G. (Eds.) Proceedings of the 2000 Quality in Postgraduate Research Conference. Adelaide. Pp 165 -177.

– Zuber-Skerritt, O. and Knight, N. 1992a. Helping postgraduate students overcome barriers to dissertation writing. In Zuber-Skerritt, O. (Ed). Starting Research: Supervision and Training. University of Queensland: The Tertiary Education Institute.

– Zuber-Skerritt, O. And Knight, N. 1992b. Problem definition and thesis writing: workshops for the postgraduate student. In Zuber-Skerritt, O. (Ed). Starting Research: Supervision and Training. University of Queensland: The Tertiary Education Institute.

– Jansen, JD. 2009. 20 Tips for effective supervision. Workshop presented at the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, 20 November 2009

—

Next Chapter – Chapter Three: http://rozenbergquarterly.com/?p=1873