Rembrandt van Rhijn

Tolerance ranks high among the markers of being Dutch. In paintings of Rembrandt van Rijn one can possibly see that he was liberal and tolerant (Hoekveld-Meijer). Many scholars and politicians maintain that the Netherlands has a tradition of tolerance that harkens back to the 17th Century, generated by the Dutch tradesman spirit.

‘It’s a misconception that the Dutch are essentially racist and that they discriminate’ (Derksen, 2005, 38; italics mine -ldj). Paul Scheffer, who coined the concept of ‘a multicultural drama’ in the Netherlands, upholds his confidence in the Dutch: ‘Most people have essentially nothing against the presence of immigrants, and they want to live peacefully with them (Hooven, 2006, 112; italics mine -ldj). These reassurances of the Dutch being essentially good people may be an indication that nowadays the Dutch tend to behave differently than in the immigrant era of the 17th Century, suggesting that the Dutch have temporarily wandered off from the correct Dutch course. This Golden Century, as it is called in the Netherlands, still serves as a rich source for Dutch identity construction.

Being Dutch is clad with undisputed and rather sturdy securities: the rule of law, individual freedoms, social and healthcare securities, free education and leisure time, and guaranteed subsistence levels. These securities and services are constantly scrutinized, subject to political debate and parliamentary decision, and balanced with a significant tax burden to maintain Dutch Wonderland, upgraded one day or downgraded the next. Dutch Wonderland did not just happen; it is a complex political construction that requires ideological drive and savvy political skills.

All told social solidarity has for decades been a cornerstone of Dutch politics. A hundred years ago free education and voting rights were defining issues on the Dutch political agenda, complemented with minimum wage; low premium health insurance (Amsterdam first, in 1846; Health Insurance Fund for labourers, in 1870); unemployment benefits; public housing (Woningwet 1901); rent subsidies (Wet Individuele Huursubsidie 1986); and old age pension (AOW, for residents 65 and over; since 1957). These rights and services are found in most Western European countries, though in varying degree. The Netherlands stands out in particular with regards to public housing, provided by Housing Corporations. As part of their building activities, these Corporations are bound to provide social housing, including its maintenance. At the end of the 1990s 36 % of all housing in the Netherlands was classified as social housing against a European average of just 18 % (Duijndam, 2009, 31). In 2004 the Netherlands’ social housing share had fallen to 34 %, yet the shares in other European countries were still much lower: Italy 5 %, France 17 %, Germany 5 %, Denmark 19 %, and the United Kingdom 20 %. Over the years a political majority within the Dutch multi-party system agreed to keep this social edifice standing, financed with public funds, general taxes or specific premiums.

According to a recent study Americans spend twice as much as residents of other developed countries on healthcare, but get lower quality, less efficiency and have the least equitable system. The Netherlands ranked first overall on all measures of healthcare-quality, efficiency, access to care, equity and the ability to lead long, healthy, productive lives. Better than Britain, Canada, Germany, Australia, New Zealand and the USA.

Well-Off

The tax burden of Dutch Wonderland does not stand in the way of living well. A recent study by the Netherlands’ Central Planning Office compares the social and economic indicators of the Netherlands with those of other countries. These countries are grouped into the Scandinavian (government) model, the Continental (corporate or Rhineland) model, the Mediterranean (family-oriented) model and the Anglo-Saxon (free market) model. This study summarizes ‘that a high tax burden is quite compatible with a high level of welfare and prosperity. In nearly all respects, the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands outperform the Continental, Mediterranean and Anglo-Saxon countries. Poverty is low, older people are better off, there is less discrimination, and the level of health care and education is higher. These countries score high on the European Union “Lisbon” agenda (2009) of social cohesion, economic resilience and dynamism’ (Cnossen, 2009).

USA expatriates who live and work in the Netherlands are at first stunned by the maximum rate of the tax they have to pay on their income: 52% (Shorto, 2009). After a while they count the blessings of what government returns: monies for child benefits, school-materials, and children’s day care; vacation money on top of salary and a minimum of 4 weeks vacation; universal healthcare with hardly any co-payments. Shorto, himself an American expatriate for some years, observes: ‘The Dutch seem to be happier than we are’, quoting a 2007 UNICEF study of the well-being of children in 21 developed countries that ranked Dutch children at the top and American children second from the bottom (UNICEF, 2007). Nonetheless, vociferous dissidents argue that the Netherlands’ social safety net is in tatters because of the game of free marketeers that has replaced government care and provision. People, who are not fit to survive on their own, or who lack the merits to compete in free markets, the unproductibles (onrendabelen) as it were, are falling through the cracks (Dam, 2009).

Knowing that the best is not good enough, and that Dutch comforts may have been better in the past, or even need repair, the Dutch are well off by almost all standards of personal freedom, individual security and social wellbeing. Against this illustrious background of a Dutch Wonderland, the Dutch sense of insecurity about their present day identity – who are we? – may appear hard to understand. Equally surprising is the lack of Dutch imagination of who do we want to be?, addressing the futuristic flipside of their identity complex.

Power of Imagination

The imagination of what it means to be Dutch is powered by a strong historical remembrance. In 2006 the Netherlands’ Prime Minister called upon the VOC mentality of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie; VOC) that existed in the days of the 17th Century when Holland ruled the waves. In reaction to parliamentary opposition he argued: We can do it again!, claiming success for his government coalition, and attempting to perk up the nation. The 17th Century ‘was surely the “Golden Age” of the Dutch slave trade’ when taking together both slave trades, by the VOC and the Dutch West India Company (West Indische Compagnie; WIC) (Wely, 2008, 71). In this recall the Prime Minister did not pay much attention to Dutch descendents of the slave trade of the Dutch West India Company, living in the Netherlands and on Dutch Caribbean islands.

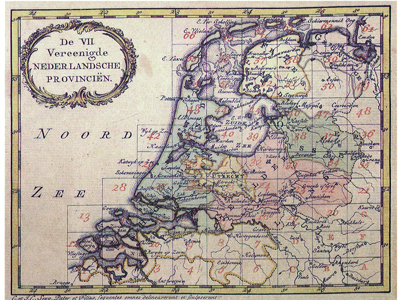

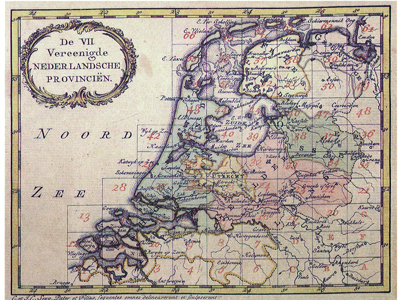

Republiek – kaart

The immigrant character of Dutch society in the Golden Century has been chronicled by Jonathan Israel (Israel, 1998, 623-628). In this century student enrolment at the universities was for a substantial part foreign born, especially at Leiden. During the quarter 1626-1650 more students at Leiden’s university were foreign born than Dutch (Israel, 1998, 901). The manpower employed in Dutch shipping could be sustained only by means of continuous and large-scale immigration. Despite the rising level of immigration from the inland provinces, most immigrants in Amsterdam continued to be foreign born. In the 1650s more foreign-born men married in Amsterdam than newcomers born in the Dutch Republic outside Amsterdam. This was also the case in the 1690s. More than 40 % of the seamen employed by the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie in the 1650s were foreign born. The navy was heavily reliant on foreigners. The towns in Holland and Zeeland competed for Huguenots from France – and their money and skills – with each other and also with other inland towns. Huguenots amounted to 7 % of the population of the large towns. 17th Century Dutch cities were populated with large numbers of immigrants, and that for good economic reason.

A boost to Dutch identity has been the recent interest in New Amsterdam (1626-1664) as the center of the world, where it all began – that is, for New York and America. Russell Shorto wrote a polished and charming story of New Amsterdam, Dutch Manhattan and the forgotten colony that shaped America. He emphasizes ‘the crucial role of the Dutch in making America what it is today‘ (Shorto, 2004, book jacket). Shorto describes the 17th Century Netherlands’ provinces as the melting pot of Europe where immigrants from all corners in Europe settled, learned the Dutch language, took on a Batavian name; it was essentially a world where others could also have a place. This appealing image Shorto projects on New Amsterdam, and argues that much of this legacy is still to be found in present day New York: ‘The Dutch colony was one of the most culturally mixed places on earth in the 17th century – by one account, 18 languages were being spoken in the streets of New Amsterdam at a time when its total population was perhaps 500 – and this diversity provided the stock for New York’s ethnic stew. Factionalism being the essence of politics, New York thus had in its founding the ingredients to make it the nation’s laboratory of political ideas.’ Thanks to the Dutch, at least in the eye of the beholder!

Shorto argues that ‘America’s first mixed society never really went away but is woven into the nation’s DNA.’ His story is uploaded with Dutch cookies, Speculaas and Sinterklaas (Santa Claus). He romanticizes the 17th Century Dutch settlers as the forgotten Pilgrims, or the Un-Pilgrims, whose multicultural history competes still to this day with the puritanical legacy of the Pilgrim Fathers. He calls upon an image of a Dutch way of life in a small settlement on the coast of America, New Amsterdam, with freedom of conscience, imposed by grand merchants in Holland, to explain today’s New York liberalism. According to Shorto, this Dutch footprint certifies the American divide between Puritanism and Liberalism. He claims that 17th Century Dutch identity still has an impact in present day New York, or even the whole of the USA.

Shorto contrasts the Pilgrim Fathers’ legacy with early 17th Century Dutch liberalism imported to New York. The bearers of the Pilgrim’s legacy had their goal to keep the barbarians outside, and the social order unchanged, in a nostalgic imagination of the past. The puritanical fear of immigrants who will demographically overrun the WASPs (White-Anglo-Saxon-Protestant) feeds fierce opposition to USA federal government’s attempts at legalizing undocumented immigrants in the first decade of the 21st Century. Yet in New York, all immigrants, including the undocumented immigrants, are welcome: They are America. In 2010, Bloomberg, New York’s Mayor, repeated this once more: ‘No city on earth has been more rewarded by immigrant labor, more renewed by immigrant ideas, more revitalized by immigrant culture.’

This sharply contrasts with immigrant anxiety in other parts of America (Caldwell, 2009, 340). Over there the plight of a legion of ca.12 million illegal immigrants is extremely uncertain. In some states rumours about raids on illegals are causing wild flight; children are abruptly taken from school; workers flee their workplace; families go underground: ‘a 14-year-old told [that] she and her parents live in constant fear.’ Federal initiatives to legalize undocumented immigrants, mainly Latinos, were answered in 2006 by local authorities with arbitrary controls, which delivered scores of illegals into the hands of immigration authorities, to be locked up in detention centres before being deported. Caldwell asserts, ‘the American public still does not like immigration’, when quoting a 2006 poll by the Pew Research Center that a majority of Americans – 53 % – think all illegal immigrants should be required to go home (Caldwell, 2009, 340). Making such an eye-catching statement, Caldwell overlooks the fact that immigration and illegals are not in the same bracket. Even so, thanks to the footprint the Dutch left centuries ago in New Amsterdam on the Hudson, New York still stands out as a haven for immigrants. Imagine that! What once was Dutch is no more, at least not in the Netherlands on the North Sea but still manifest in a Dutch footprint in the USA.

The open-minded liberalism that New York supposedly inherited in the 17th Century from far away Holland fails to manifest itself these days in the Netherlands. Today the Netherlands seems on better terms with the rest of the USA where: ‘… some have warned that in their opinion the nation’s cultural identity could be washed away by a flood of low-income Spanish-speaking workers from Central and Latin America.’ Statements about cohorts of non-western immigrants and Muslims threatening Dutch identity must sound pretty familiar to those Americans. Apparently the power of imagination is able to bridge the Atlantic and several centuries in time, but loses its magic close to the original Dutch home.

Just some forty years ago the Dutch live and let live state of mind in the 1960s and 70s perfectly fitted Shorto’s image of 17th Century Holland and New Amsterdam. And present day Dutch liberalism as well as the Netherlands’ welfare state outshine The American Way and New York, New York (Minelli, 1977) in respectable differences. By many standards the Dutch consider themselves a well-endowed nation indeed. Tamimi Arab recalls the medal of enlightenment the Netherlands earned by being safe haven for Spinoza, Voltaire, Bayle and Locke, at a time when most of Europe still wandered in darkness. Also today the Netherlands is a liberal forerunner, especially when compared to the USA with its divisive controversies over abortion, euthanasia, soft drugs and same-sex marriage. The Netherlands sits on the just side of history; a guide to the rest of the world indeed (Tamimi Arab, Eutopia, 2009)!

Illustrative of how good the Dutch feel about themselves is ‘Simon’, a Dutch movie by Eddy Terstall (2006), portraying Amsterdam as a sunny city of relaxed people, abundant love and sex, fun and leisure, and gay marriage. The Dutch are portrayed with savoir vivre. Simon, the movie’s main character, a truly life-loving character in his forties, is diagnosed with an incurable brain tumor. The movie details his decision of being euthanized, according to a legally recognized protocol of how to do so, which includes assistance of professional medical and ethical staff. In his final moments, family, children and friends, who all have agreed with his decision, surround Simon, showing respect for a beloved person’s chosen end-of-life event.

Euthanasia is practiced as an extension of personal freedom, under strictly defined and controlled conditions. The same applies to abortion. Capital punishment is outlawed and considered not right in a civilized society. The use of soft drugs is a personal matter, hard drugs are forbidden. When people want to marry, they do so according to preference, be it to a man or a woman. Most of these attainments are carried by a large consensus, including Catholics and Protestants of various shades and grades. A social welfare net takes care of people who cannot take care of themselves. Pensions are secure, and based on real accumulated capital, not on paperwork. The Netherlands figures in the highest ranks of providing development aid to poor countries.

Elsewhere these Dutch values and practices have caused condemnation of the Lowlands (sic) as a deranged country, a NARCO state, a country where the unborn, elderly and disabled may just be terminated. These overstuffed images of the Dutch are debatable; they vary with the mindset of the beholder. More often than not, the level of actual information does not matter. Yet it cannot be denied that a wide consensus prevails that the Netherlands’ public authorities facilitate liberties where other states put restrictions in place. The Netherlands is by many standards a liberal nation. Precisely this being so raises the question: why are the Dutch so liberal for themselves and have become so cramped about the presence of the non-western Dutch? Could it be that the true Dutch are preoccupied with what they own, and that they fear their social and liberal achievements being endangered by the numbers of non-western immigrants on their home turf? The question remains whether an un-doctored True Dutch legacy can be identified. One day the Dutch believed to be a guide to the world, the next day the closing of the Dutch mind shocks the world. Over the years an abundant number of respectable doctors have become talking heads on the subject of Dutch identity, all making sense of their particular conception of Dutch Wonderland.

Malleable Legacies

Malleable Legacies

Of course it feels good to be Dutch when viewing the legacy of great Dutch painters in the 17th Century, Rembrandt van Rijn, Frans Hals, and Johannes Vermeer (just to name a few). Or perhaps when counting the blessings of the hundreds of years of water management (barriers, waterways, levels, and water quality) that keep feet dry in a country of which 20 % is below sea level. Dutch water control boards (waterschappen or hoogheemraadschappen) are among the oldest forms of local government in the Netherlands, some of them having been founded in the 13th Century. A definitive pacification of religious adversary by the Peace of Westphalia treaties in 1648 brought peace. Much later – in the 1950s – the Dutch welfare state provided for people in need. These instances reconstitute a good feeling to be Dutch; they actually articulate the best about being Dutch.

One may feel Dutch, more or less, which is to be distinguished from the fact that one is Dutch by firm proof of being a Netherlands citizen with a Dutch passport and voting rights, who pays steep taxes and has access to excellent healthcare, good education and generous provisions of the Dutch welfare state. These attributes constitute the hardware of one’s identity, which is run by software that facilitates how to operate being Dutch, or being an American. For instance, an American of Asian ancestry, born in Britain, who had become a USA citizen living in the USA, stated that he felt he was an American indeed: ‘Yes, more or less; not so much during the Bush years, but with Obama at the helm much more.’ This American expressed a political underpinning of his American identity, which fluctuated, depending upon who was elected to the White House. Some days he felt more American than other days. One can feel more or less Dutch, but not by who is heading the state, as the Netherlands is a Kingdom with hereditary succession. Yet the King’s hereditary succession may be evaluated differently; an antiquated relic of bygone times, or a treasured symbol of historic continuity, national unity and Dutch identity. In other words, the King’s significance is also in the eye of the beholder, for some a relic, for others a national symbol, and at the time of USA independence at the end of the 18th Century, a British institution to do away with.

Being Dutch does not exclude moments when it does not feel good to be Dutch, for instance when bringing to mind Dutch participation in the slave trade during the 17th and 18th Century; or the Dutch fighting – and losing – a colonial war in Indonesia in the second half of the 1940s, which was euphemistically toned down to Police Actions (Politionele Acties). Or the Dutch collaboration with the Nazis in the Holocaust, sending Dutch Jews to death camps during the German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940-1945. Though the interpretation of these episodes in Dutch history vary, they carry for many people no added value to their Dutch identity. On the contrary, some feel to be ashamed to be Dutch in the face of these histories; they put a distance between their Dutch identity and Dutch dark episodes. In other words, for them being Dutch basically amounts to positive assets, something to feel good about or even to be proud of. They feel uneasy or deceived by histories of Dutch crimes and misdemeanours, as if these dark spots should not be part of Dutch identity. To feel good again about being Dutch, these histories must be covered up, embedded in the particular conditions of their time, smoothed over, or reconstructed.

A head on confrontation with historical black pages may serve as an alternative process to cleanse the seamy side of one’s national identity. This painful face-to-face encounter may enable one to draw a line, and make a new start, to feel good again. A case in point is the Historikerstreit (Historians dispute or Historians controversy) in Germany since the 1980s about the variance in understanding the rise and crimes of Nazi Germany culminating in World War II (Kershaw, 2008). In her study German National Identity after the Holocaust, Mary Fulbrook summarizes the historians’ controversy as a difference on ‘normalization’ of history for the sake of German identity construction (Fulbrook, 1991, 101-141). Conservative historians demanded a ‘normalization’ of the past and a relativization of Germany’s crimes, to resurrect some pride again in being German. They argued that Germany was not uniquely evil and should be freed from the enormous burden of guilt; German history should be ‘normalized.’ One of them, Stürmer, entered a plea for the re-appropriation of history for the construction of national identity, which he judged as morally legitimate and politically essential. Jürgen Habermas, among others, countered these attempts by presenting a scathing critique of such ‘apologetic tendencies.’ Habermas opposed a single historical interpretation (by government fiat), and made a plea for western values and ‘constitutional patriotism’ as the basis of West German identity. The German Historikerstreit was in its core a battle over how to reconstruct German identity after World War II, ‘the past which refuses to become history.’

Historiography is not a straightforward bastion upon which identity construction can rest. One feels Dutch, more or less, according to how one personally appreciates specific historical and actual conditions. These conditions are not a given, but pass a reality check in the course of a selective process in which many agents play their part: historians and educators; politics and circumstance, media and academe, resulting in a cluster of consensuses at any given moment in time. Exemplary of this selective process is the change in consensus on Dutch behaviour during German occupation from 1940-1945. Until the 1970s a consensus prevailed on brave Dutch resistance during the occupation years. This consensus was dispersed when accounts of widespread indifference and more than incidental collaboration with the Nazis could no longer be overlooked. These accounts did not correspond with the Dutch resistance image. In addition to documentation of heroic acts of resistance, indifference to the plights of the Jews, looking away, and active collaboration with the Nazis became part of Dutch history – though rather hesitantly.

Equally striking was a changeover in the perception of the overseas refuge of the Dutch government. Cabinet, Queen and family went into exile during the days of the German invasion in May 1940, and sought refuge in England and Canada during the war years. At first many people were stunned when hearing of this royal departure, but during the occupation and the first decades since, a public relations campaign steered attention to the bravery and the encouragement of Queen Wilhelmina’s radio talks and those of the Dutch Prime-Minister from their safe haven in London to the Dutch people in occupied territory. A few weeks after the German invasion, a Royal Court minister concocted a poem that actually lauded the Queen’s departure, which became an instant popular success:

No, You did not Flee.

But followed God’s call

I don’t ask what You have been through

A Struggle, so heavy, so deep

The mayor of Zwolle, a medium size city, who had in May 1940 expressed his bewilderment about the royal getaway, was never forgiven. During the war he was arrested by the German authority for obstruction, and subsequently removed from office. After the war his 1940 faux pas stood in the way of his being reinstalled in a similar position by the Dutch authorities.

Decades later some historians reviewed this exile of government as an abandonment with dire consequences, leaving the country in the hands of the Secretaries-General, senior Dutch officials, who by their bureaucratic nature and signature were more inclined to follow the commands of the occupying authorities (Zee, 1997). They engaged in a form of tactical collaboration, thus unwittingly lending legitimacy to anti-Semitic laws by tacitly condoning them and supplying Dutch bureaucrats and police in order to implement them (Oliner, 1992, 34-35). How much of the Dutch Jewish death-camp score under Nazi-Germany can be attributed to the abandonment proposition is impossible to estimate; nonetheless this feature has now become, belatedly, part of Dutch history of the German occupation of 1940-45. The image of a Dutch nation, all bravely standing up to the Nazis, is more nuanced with dark shades of civic indifference, bystanders, bureaucratic collaboration and government abandonment. Both sides of the picture still hold, depending on what is told, what one knows, and what one prefers to know or to believe. History’s contribution in answering national identity questions about who are we? is not straightforward, yet it serves as a rich reservoir to work with, for better or worse.

Next Time: A Dutch-European Canon

For long, the consumption of Dutch history was a common affair with little controversy and ideological prescription, a matter of course. But with the rise in education, the decline of traditional authority and the recognition of an immigrant presence, Dutch history became questioned by critical minds; it became a partisan subject, just as elsewhere, for example in the US. In 2010 the Texas Board of Education tried to put a conservative stamp on history and economic textbooks, stressing the superiority of American capitalism, questioning the Founding Father’s commitment to a purely secular government, and presenting Republican philosophies in a more positive light. The conservative Board members maintained that they were trying to correct what they saw as a liberal bias among the teachers. In previous years an ideological battle over Darwinism and the separation of church and state had divided the Board. Efforts by the large Hispanic population to have its presence accounted for were defeated: ‘They [Texas Board members] can just pretend this is a white America and Hispanics don’t exist […] they are not experts, they are not historians […].’ A protest rally called ‘Don’t White-Out our History’ included the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In ‘Rewriting History in Texas’, an editorial in the New York Times emphasized that students deserve to have a curriculum chosen for its educational value, not politics or ideology.

Also the Netherlands has begotten a heterogeneous nation where history is no longer taken for granted. Omnipotent pressures of immigration and globalisation have invigorated a need to bolster knowledge of Dutch culture and history, or as some say, to (re-) write Dutch history. This resulted in a government enterprise, assigning a group of academics the task to select significant moments in Dutch history, to be included in a Dutch Historical Canon, not so much as an historical guideline but rather as a selection of chapters that could be opened to learn more about significant Dutch episodes. The Canon of Dutch History was developed in the early years of the 21st Century to inform the Dutch and the Netherlands’ immigrants in a systematic way on Dutch history and culture. The Canon aimed at a minimal body of knowledge that all Dutch people must be familiar. Interestingly the Canon Committee pointed out that ‘Netherlands’ and ‘Dutch’ are rather recent concepts without long-term historical depth; these concepts contradict that this region was all along a ‘Dutch’ entity (Note on Outline of the Canon):

It is important to use terms like “Netherlands”, “Dutch culture” and “Dutch history” with careful consideration. Until the nineteenth century the term “Netherlands” is an anachronism, and the adjective “Dutch” for the early history remains problematic. Any reference in this text to the history of the Dutch language and culture, the Dutch territory and the Dutch state, in fact means, “pertaining to this region”, without suggesting that this region was all along a cultural, political or linguistic entity. These topics are treated as historical phenomena.

The Canon is based – as a matter of course – on a selective historical narrative, with 14 headlines, the first one Lowland by the Sea, about the struggle against water, and the last one Netherlands in Europe, and 50 chapters detailing the headline in specific emblematic episodes and happenings. According to the Canon makers the following headlines present Netherlands’ history:

Lowlands by the Sea

On the periphery of Europe

A Christianized country

A Dutch language

An urbanized country and a trading hub at the mouth of the Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt

The Republic of the United Netherlands: arisen by revolt

The glory of the ‘ Golden Age’

Merchant spirit and colonial power

Unitary state, constitutional monarchy

The emergency of a modern society

Netherlands in a time of world wars: 1914-1945

The welfare state, democratization and secularization

Netherlands gets colour

Netherlands in Europe

Some have qualified this canonization as a provincial fear for change, intellectual poverty and official dirigisme. Others considered the Dutch Canon as teaching material designed by the True Dutch for the immigrant populations, serving as a demarcation of the Dutch homeland. Even so, the Canon enjoyed a remarkably positive reception.

‘The Netherlands never existed’ was a tantalizing comment in one of the Canon reviews. Most of the 50 specific chapters cover border-crossing history, exemplifying that Netherlands’ history is shared with other nations; it is not happenstance but interconnected with history elsewhere, sharing persons, circumstances and activities. Unmistakably the Canon Committee was partial to the view that there have never been good old times that the Dutch were among themselves, in isolation, sticking together around the fire. The Committee’s compilation of the Canon implies that there has never been a pure Dutch identity, untainted by foreign elements (van vreemde smetten vrij).

In retrospect the Canon Committee stated that it steered away from connecting the historical Canon with national pride and identity. In an inflammable climate (such as in the Netherlands) one person’s pride could easily be interpreted as a declassification or exclusion of the other. But, the Committee added, the Canon does reflect indeed some collective identity with which people may feel connected. The Committee argued that the Canon may very well support a civilized form of Netherlands’ citizenship and self-awareness, provided that such goes hand in hand with a sense of relativity as well as an open eye for the black pages in Netherlands’ history. According to the Committee, such a Canon undoubtedly contributes to responsible Netherlands’ citizenship (verantwoord burgerschap) that includes all. By emphasizing all-inclusive responsible citizenship, the Canon distanced itself from the integration discourse, which makes a special distinction for immigrants who must integrate. The Canon founders followed the politically correct mode that responsible citizenship must ‘keep things together’, applicable to all Dutch people, irrespective of color, ethnicity and origin.

By its nature the Dutch Canon touches only lightly on the living history of changes at home as well as in the rest of the world that impact Dutch identity: Netherlands gets colour, and Netherlands in Europe. It is precisely this living history that calls for a redefinition of Dutch identity. However meaningful for educational purposes, the retrieval of Dutch histories to sustain responsible citizenship is lopsided. Dutch nationals, some more than others, are increasingly affected by globalization. They can no longer evade the fact that the terms of Dutch identity are challenged by the porosity of national borders, going hand in hand with a deepening democratic deficit on the ground. Bolstering responsible citizenship must take the changing national and international stage into account, its present-day playing field. For too long the thickening of international relations (Hirsch Ballin, 2005, 12) and economic preponderance has been left out of the equation, which induced the prevalent sense of insecurity, causing many of the Dutch to be prey to populist appeals. The efforts put into an educational Dutch Canon call for a follow up of a Dutch Global Vista to assist the Dutch in grasping where they are going and who they want to be. No doubt, such an assignment comes close to walking on water, as it demands the impossible task of fixing the future.

Responsible citizenship that is confined to the Netherlands local domain is a contradiction in terms. Netherlands self-government is an illusion; Dutch government is essentially local government that operates under layers of powers imposed from outside, more or less beyond Dutch control. Dutch national democracy as well as Dutch national citizenship has limited purview. This may explain the lack of trust many Dutch citizens have in Netherlands’ social institutions. Responsible citizenship requires a futuristic window, not frozen in local time, but an imaginative work in progress, evolving as time goes by. To begin with a Dutch-European Canon might help the Dutch to understand how much of their Wonderland has been wrought by European governance. Within a European context the Dutch are Dutch-European citizens with a ‘hyphenated’ citizenship that yet has to be developed as a cornerstone of a Dutch identity. They must become aware that their bread is buttered on both sides of the hyphen (Caldwell, 2009, 338). From the point of view of responsible citizenship a Dutch-European Canon certainly must include a headline European Democracy, raising red flags to those who still think that all politics is local. Building Dutch-European responsible citizenship would require that a European Union wide political platform be formed to tackle Europe’s democratic deficit. This should be a prime concern for Netherlands’ politics on responsible citizenship. It is not.

‘Who do we want to be?’

Any definition of Dutch identity is immediately questioned: so many heads, so many minds (zoveel hoofden, zoveel zinnen). These differences are a reflection of a high degree of political and societal pluralism. Recognition of difference in opinion and belief is deeply anchored in the Netherlands law (Government Paper, 2008, 6). The reality of Dutch politics is that any Netherlands’ government is built on a coalition of partners who together have achieved a majority; it is a fractioned majority, a sum of minorities. Respecting the rights, opinions and votes of minorities is therefore a cornerstone of Netherlands’ democracy and politics. At the same time, typical Dutch characteristics are recognized in unison as typically Dutch: tolerance; open-mindedness; wealthy but stingy; un-heroic; cleaning the stoop and all that, but not the armpits and the rest (Huizinga, 1935, 14).

In 1935, Jan Huizinga wrote about the Netherlands’ spirit and soul (Nederland’s Geestesmerk) and marked being un-heroic as a basic characteristic of the Dutch character (volksaard). Even heroes as Piet Pieterszoon Heyn (Piet Heyn) who conquered in 1628 La Flota, the Spanish Treasure Fleet, kept a modest demeanour. How could it be different, Huizinga asked. States that are built on well-to-do burghers living in relatively small cities and reasonably content farmers’ communities [in 1935; now no more] are no breeding ground for what one labels heroic. Commitment and a sense of duty suffice for the Dutch. That explains, according to Huizinga, their poorly developed military mindset as opposed to a much stronger trade orientation. By the way, according to Dutch history it is believed that New Amsterdam on the Hudson was not conquered, but was acquired as a business deal with American Indians! Already then the Dutch preferred business terms. Being un-heroic also fits the almost absent tendency of popular revolt, and in general the flatness of national life, but Dutch wantonness as well, the lack of good manners and being stingy (Huizinga, 1935, 8-17).

In 1935, Jan Huizinga wrote about the Netherlands’ spirit and soul (Nederland’s Geestesmerk) and marked being un-heroic as a basic characteristic of the Dutch character (volksaard). Even heroes as Piet Pieterszoon Heyn (Piet Heyn) who conquered in 1628 La Flota, the Spanish Treasure Fleet, kept a modest demeanour. How could it be different, Huizinga asked. States that are built on well-to-do burghers living in relatively small cities and reasonably content farmers’ communities [in 1935; now no more] are no breeding ground for what one labels heroic. Commitment and a sense of duty suffice for the Dutch. That explains, according to Huizinga, their poorly developed military mindset as opposed to a much stronger trade orientation. By the way, according to Dutch history it is believed that New Amsterdam on the Hudson was not conquered, but was acquired as a business deal with American Indians! Already then the Dutch preferred business terms. Being un-heroic also fits the almost absent tendency of popular revolt, and in general the flatness of national life, but Dutch wantonness as well, the lack of good manners and being stingy (Huizinga, 1935, 8-17).

Huizinga brushes up the concept liberal, meaning: all that is of value to a free man, and defines the untranslatable Dutch concept burgerlijk: all what belongs to city life, the culture that germinates and grows in cities. The Dutch are liberal and burgerlijk, city dwellers and countrymen as well. As distances are short, countryside and city population are not worlds apart. Huizinga claims that the Dutch nurture a need for simple, unadorned truth and honesty; reliability, order and harmony, in sum a need for spiritual purity. This purity correlates with the obvious Dutch cleanliness as expressed in manifold Dutch words: zindelijk; proper; frisch; net; helder; zuiver; schoon. Elsewhere this complex has been labelled as a typical feature of Dutch Calvinism. Other historians have made a different correlation, literally down to earth. As early as the 14th Century, long before Calvinism struck home, as much as 50 % of the Dutch households had some kind of dairy production, which required hygienic conditions, as a matter of economics. Spiritual purity, Calvinism and butter and cheese hygiene-economics, all speak out for the Dutch character. The biggest virtue of the Dutch, as Huizinga elects, is their high degree of respecting the rights and opinions of others, which flipside, however, is a tendency for a bit of wangle and privilege for one’s friends. Finally, to end these dated Dutch intimacies, Huizinga explicitly professes that the Dutch have shown themselves to be immune to strong expressions of political extremism (Huizinga, 1935, 8-17).

Since Huizinga’s times, that obviously has changed. More than 70 years later, Job Cohen, Mayor of Amsterdam until 2010, and known for his policy of keeping things together in a city with over 180 nationalities, also attempted to characterise a collective Dutch identity, manifest over centuries in different expressions of ‘our people’ (Cohen, 2009). Cohen’s Dutch character contains the following properties: a sense of freedom; openness for things, people, ideas and places; an external orientation: trade, travel, discovery; a live and let live sentiment; rich but pretending otherwise; and always talking about other people, neither being jovial nor too serious (zeuren). Cohen doesn’t take this Dutch character too seriously, rejecting absolutism; another characterization is possible as well. He questions which of these characteristics the Dutch may want to preserve, and which can be thrown in the dustbin because of being of no use in the 21st century. Cohen approaches the question of Dutch identity from the angle that it is a social construction, a dynamic concept, malleable, more a question of who do we want to be, than a cry for who are we? Cohen presents this activist interpretation of Dutch identity as a challenge to update a yet unchartered territory of Dutch Wonderland. How will future generations look back at the living history of today’s dominant Dutch narrow-minded identity complex? As much of the Dutch wealth is garnered across the borders of the nation, it does not make practical sense to withdraw to a home sweet home. More importantly, such withdrawal would create a bipolar disturbance from a moral point of view. Dutch Wonderland loses its shine and credibility when lacking interest and engagement to fight discrimination, segregation and gross inequalities. National identity is stamped on two sides of the same coin: who are we? while looking back in time, and who do we want to be? in view of the demands of modern times. The Dutch have to work towards an update of their identity that appreciates their local comforts and engages a world that has changed irreversibly, at home and worldwide (see Chapter 7). When Dutch identity becomes jammed in the preservation of True Dutch comforts, schizophrenia will overtake the nation. The writings on the wall are that this is indeed happening.

—-

About the author:

Dr. Lammert de Jong (1942) served 9 years between 1985 and 1998 as resident-representative of the Netherlands government in the Netherlands Antilles. Prior to this he was attached to the University of Zambia and the National Institute of Public Administration in Lusaka, Zambia (1972-1976). In the People’s Republic of Bénin, he was director of the Netherlands Development Aid Organization (1980-1984). He received a PhD in Social Sciences at the Free University, Amsterdam (1972), and published during his academic years about public administration and participation.

He concluded his civil service career as Counselor to the Netherlands government on Kingdom relations. Since then he writes as a free-lance scholar on post-colonial statehood in the Caribbean.

Being Dutch, more or less. In a Comparative Perspective of USA and Caribbean Practices –

ISBN 978 90 3610 210 0

Publications

Recent

Lammert de Jong, De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk. Over de samenwerking van Nederland met de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba (The Operations of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba). Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers 2002. ISBN 978 90 5170 586 7

Lammert de Jong, ‘Cracks in the Kingdom of the Netherlands. An Inside Story’. In: Sandra Courtman (ed.), Beyond the Blood, the Beach and the Banana: New Perspectives in Caribbean Studies. Jamaica, Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers 2004.

Lammert de Jong & Douwe Boersema (eds.), The Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Caribbean: 1954 – 2004. What next? Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers 2005. ISBN 978 90 5170 195 1

Lammert de Jong and Dirk Kruijt (eds.), Extended Statehood. Paradoxes of quasi colonialism, local autonomy and extended statehood in the USA, French, Dutch and British Caribbean. Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers 2005. ISBN 978 90 5170 686 4

Lammert de Jong, ‘De ondraaglijke lichtheid van het Koninkrijk’ (The unbearable lightness of the Kingdom). In: Christen Democratische Verkenningen. Antillen/Aruba uit de gunst. Winter 2005.

Lammert de Jong, ‘Tegen de autochtone klippen op’. In: Francio Guadeloupe & Vincent de Rooij (eds.), Zo zijn onze manieren. Visies op multicultiraliteit in Nederland. [On our own terms: Perspectives on multi-culturality in the Netherlands]. Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers, 2007. ISBN 978 90 5170 862 2

Lammert de Jong,’True Dutch’. In: London Review of Books, February 2007.

Lammert de Jong, ’Implosion of the Netherlands Antilles’. In: Peter Clegg and Emilio Pantojas Garcia (eds.), Governance in the Non-Independent Caribbean: Challenges and Opportunities. Jamaica, Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 2009.

L. de Jong, ‘Implosie van de Nederlandse Antillen’. In: Justitiele Verkenningen, De Nederlandse Cariben, WODC, August 2009.

Lammert de Jong, Being Dutch, more or less. True Dutch is not the issue. So what is? In a Comparative Perspective of USA and Caribbean Practices. Forthcoming, Autumn 2010.