ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ A Dialectical Profile For The Evaluation Of Practical Arguments

ABSTRACT: This paper proposes a dialectical profile of critical questions attached to the deliberation scheme. It suggests how deliberation about means and about goals can be integrated into a single recursive procedure, and how the practical argument from goals can be integrated with the pragmatic argument from negative consequences. In a critical rationalist spirit, it argues that criticism of a proposal is criticism of its consequences, aimed at enhancing the rationality of decision-making in conditions of uncertainty and risk.

KEYWORDS: critical discourse analysis, critical rationalism, critical questions, decision-making, deliberation, dialectical profile, policy evaluation, practical argument, uncertainty and risk

Introduction

This paper develops the analytical framework for the evaluation of practical arguments in political discourse presented in Fairclough & Fairclough (2011, 2012), where a more systematic “argumentative turn” was advocated for the field of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). It develops a proposal for a set of critical questions aimed at evaluating decision-making in conditions of incomplete knowledge (uncertainty and risk). The questions are briefly illustrated with examples from the public debate on austerity policies in the UK, following the first austerity Budget of June 2010 (Osborne 2010). For a more detailed analysis of the 2010 austerity debate, see Fairclough (2015).

Reasonable Decision-Making In Conditions Of Incomplete Information

Practical reasoning has been studied in informal logic and pragma-dialectics (Walton 2006, 2007a, 2007b; Walton, Reed & Macagno, 2008; Hitchcock 2002; Hitchcock, McBurney & Parsons, 2001; Garssen 2001, 2013; Ihnen Jory 2012) and sets of critical questions have been proposed for its evaluation. In what follows I will outline my own version of the critical questions for the evaluation of practical arguments, together with their theoretical underpinning, i.e. a critical rationalist view of the function of argument and of rational decision-making (Miller 1994, 2006, forthcoming). On this view, the function of argumentation is essentially critical and the best rational agents can do before adopting a practical or theoretical hypothesis is to subject it to an exhaustive critical investigation, using all the knowledge available to them. The decision to adopt a proposal A is reasonable if the hypothesis that A is the right course of action has been subjected to critical testing in light of all the knowledge available and has withstood all attempts to find critical objections against it. By critical objection I understand an overriding reason why the action should not be performed, i.e. a reason that has normative priority and thus cannot be overridden in the context. Essentially, criticism of a hypothesis is criticism of its consequences, not criticism of any premises on which it allegedly based. A critical rationalist view is anti-justificationist, and rationality is seen to reside in the procedure of critical testing; it is a methodological attitude.

Critical testing will necessarily draw on the knowledge or information that is available to the deliberating agents, and this is almost always limited. How should this knowledge be used if it is to enhance the rationality of decision-making? The critical rationalist answer is that knowledge should be used critically, in order to criticize and eliminate proposals, not inductively, i.e. not in order to seek confirmation of their (apparent) acceptability. Potential unacceptable consequences can constitute critical objections against doing A, unless critical discussion indicates that they should be overridden by other reasons.

Let us consider the case of risk first. If a definite prediction could be made that such-and-such unacceptable consequences will follow from doing A, this would provide an overriding reason why A should not be performed. But such definite predictions about the future are hard to make. On a critical rationalist perspective, rational decision making in conditions of risk can be made, however, without relying on probability calculations, by following a “minimax strategy” which says: “try to avoid avoidable loss” (Miller forthcoming). This can be done by insuring in advance against possible loss (e.g. insuring one’s property against various eventualities), or in the sense of making sure that there is some alternative route or some “Plan B” that one can switch to, should the original proposal start to unfold in an undesirable way, i.e. produce undesirable effects.

Unlike risk, which presupposes some calculation is possible, uncertainty does not involve known possible outcomes and frequencies of occurrence, derived from information about the past, but future developments which cannot be calculated. Incomplete knowledge manifests itself in this case not only as “known unknowns” but also as “unknown unknowns”, and it is impossible to predict how the proposed action, as it begins to unfold, might interact with these. Economic policy, for example, involves primarily uncertainty rather than risk, as it unfolds against a background of unpredictable world events about which little if any calculation of probability can be made. The critical rationalist answer (Miller forthcoming) to the problem of uncertainty says that it is more reasonable to choose a proposal that has been tested and has survived criticism than one which has not been tested at all. In conditions of bounded rationality, a sub-optimal (“satisficing”) solution that is known to work, if available, is preferable both to an extended quest for a maximally rational solution or to the adoption of an untested, new proposal, however promising that proposal may seem.

Critical Questions For The Evaluation Of Practical Arguments

In pragma-dialectics (van Eemeren 2010), dialectical profiles are normative constructs associated with particular argumentation schemes. They are systematic, comprehensive, economical and finite. In light of my methodological commitment to critical rationalism, according to which “rational decision making is not so much a matter of making the right decision, but one of making the decision right” (Miller 1994, p. 43; Miller 2006, pp. 119-124), critical testing of a proposal by means of an ordered and finite set of critical questions should aim to enhance the rationality of the decision-making process, not to produce the “most rational” decision (Fairclough & Fairclough 2012, pp. 49-50).

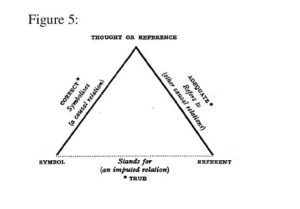

I start from the (presumptive) practical argument scheme originally defined by Walton (2006, 2007a), which I am re-expressing as argumentation from circumstances, goals (underlain by values or some other normative source) and a means-goal relation (Fairclough & Fairclough 2012). This structure can be represented as follows:

The agent is in circumstances C.

The agent has a goal G.

(Goal G is generated by a particular normative source.)

Generally speaking, if an agent does A in C then G will be achieved.

Therefore, the Agent ought to do A.

A fundamental distinction is made by Walton (2007b) among three types of critical questions: questions that challenge the validity of the argument, questions that challenge the truth of the premises and questions that challenge the practical conclusion. Along these lines, I am suggesting that challenging the practical conclusion is the most important type of testing, as it is the only one that can falsify (rebut) the practical proposal itself. It can do so, I argue, by means of an argument from negative consequence, i.e. a counter-argument, or an argument in favour of not doing A:

If the Agent adopts proposal A, consequence C will follow.

Consequence C is unacceptable.

Therefore, the Agent ought not to adopt proposal A.

Practical reasoning is a causal argumentation scheme (van Eemeren and Grootendorst 2004): the proposed action A will presumably result in such-and-such effect. But actions have both intended and unintended effects, and the same effect can result from a multiplicity of causes. First, the unintended effects can be such that the action had better not be performed, even if the intended effect (goal) can be achieved by doing A. If this is the case, then a critical objection to A has been exposed and the hypothesis that the agent ought to do A has been refuted. Secondly, among the alternative causes (actions) leading to the same effect, some may be preferable to others. If this is the case, as long as the goal and unintended consequences are reasonable, there is no critical objection to doing A, but some comparison between alternative proposals is possible so as to choose the one which is better in the context.

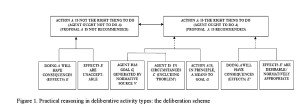

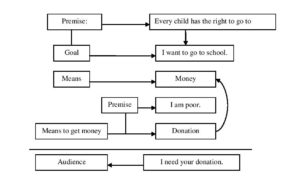

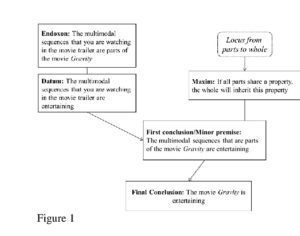

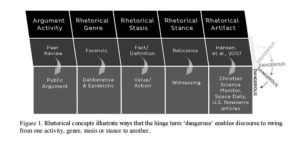

In deliberative activity types, the argument from goals and circumstances and the argument from negative consequence are related, I suggest, in the following way (Figure 1): the argument from negative consequence (on the left) is testing the practical conclusion of the argument from goals and circumstance (centre) and can rebut that conclusion, if the undesirable consequence should constitute a critical, non-overridable objection against doing A.

If however the consequences are not unacceptable, then the agent may tentatively proceed with A, on the understanding that the proposal may still be rebutted at a later stage. The conclusion in favour of doing A can be thus strengthened by a presumptive argument from positive consequence (right-hand side). Saying that the effects are not unacceptable means that critical testing has not uncovered any critical objection to doing A: achieving the stated goals would (on balance) bring benefits, and the side effects would also be positive (on balance), as far as we can tell.

Deliberation is commonly said to involve a “weighing” of reasons, and the conclusion is said to be arrived at on balance. Against a context of facts that both enable and constrain action, and in conditions of uncertainty and risk (all of these being circumstantial premises), what is being weighed is the desirability of achieving the goals (and possibly other positive outcomes) against the undesirability of the negative consequences that might arise. Non-overridable reasons in the process of deliberation include any consequences that emerge on balance as unacceptable (e.g. unacceptable impacts on other agents’ non-overridable goals), as well as unacceptable impacts on the external reasons for action that agents have in virtue of being part of the social institutional world, what Searle (2010) calls deontic reasons – commitments, obligations, laws, moral norms. As institutional facts, these are supposed to act as constraints on action; going against them (e.g. by making a proposal that goes against the law or infringes some moral norm) is arguably unreasonable.

I suggest the following deliberative situation as a starting point: an Agent, having a stated goal G in a set of circumstances C, proposing a course of action A (or several, A1, … An) that would presumably transform his current circumstances into the future state-of-affairs that would correspond to his goal G. Based on everything he knows, the agent is conjecturing that he ought to do A1 (or A2 or An) to achieve G. In order to decide rationally, the agent should subject each of these alternatives to critical testing, trying to expose potentially unacceptable negative consequences of each. If one or more reasonable proposals survive criticism, and are thus judged reasonable, the agent can then also test the arguments themselves, to determine whether any additional relevant fact in the particular context at issue is defeating the inference to the conclusion that he ought to do A1 (A2 … An) in that context.

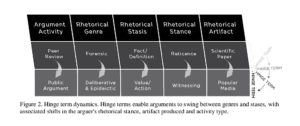

What is being evaluated, therefore, is primarily the proposal itself (the practical conclusion), and the way to do this is by examining its (potential) consequences. If more than one reasonable proposals have been selected, the arguments on which these proposals claim to rest can be evaluated as well, in order to choose the proposal that seems to satisfy a range of relevant concerns comparatively better than the others. A particular view of human rationality can be said to go hand-in-hand with this dialectical profile, a conception of bounded rationality (Simon, 1955; Kahneman, 2011): agents are reasonable in adopting a satisfactory (or “satisficing”) solution rather than in engaging in an extended quest for a “maximally rational”, “optimal” one. The point of asking the sequence of questions in the profile is therefore not to narrow down a range of alternative proposals to the one and only “best” one, but primarily to eliminate the clearly unreasonable ones from a set of alternatives. Critical testing will therefore fall into three kinds (Figure 2):

(1) Testing the premises of the argument from goals and circumstances, as a preliminary step to assessing the reasonableness of a proposal that should be able to connect a set of current state-of-affairs to a future state-of-affairs. This is needed because the proposal may be reasonable in principle, i.e. without unacceptable consequences, but may have little or no connection to the context it is supposed to address, and may therefore not be a “solution” to the actual “problem”.

(2) Testing the practical conclusion of the argument from goals, via a deductive argument from negative consequence. Applied recursively, this may lead to the rejection of one or more proposals and deliver one or more reasonable proposals for action (or none). The dialectical profile begins with the question aimed at the intended consequences of the proposal (here, CQ4).

(3) Testing the validity of the argument from goals, in order to choose one of the reasonable alternatives that have resulted from testing the practical conclusion; at this point, the critic will be looking at other relevant facts, besides those specified in the premises (e.g. other available means), that may indicate that doing An does not follow, thus suggesting that another reasonable alternative should be considered.

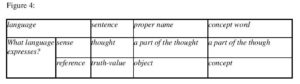

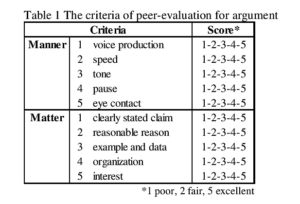

Challenging the rational acceptability (‘truth’) of the premises

(CQ1) Is it true that, in principle, doing A1 … An can lead to G?

(CQ2) Is it true that the Agent is in circumstances C (as stated or presupposed)?

(CQ3) Is it true that the Agent actually has the stated/presupposed motives (goals and underlying normative sources)?

Challenging the reasonableness of the conclusion

(CQ4) Are the intended consequences of doing A1 … An acceptable?

(CQ5) Are the foreseeable unintended consequences (i.e. risks) of doing A1 … An acceptable? [If not, is there a Plan B, mitigation or insurance strategy in place that can make it reasonable to undertake A1 … An?]

Challenging the inference

(CQ6) [Among reasonable alternatives,] is An comparatively better in the context?

Figure 2. Critical questions for the evaluation of practical arguments

The critical questions (CQ) are summed up in Figure 2 and illustrated below:

CQ1 Is it true (rationally acceptable) that, in principle, doing A leads to G?

“Doing A leads to G” is a soft generalization that can be tested against all the information at the critic’s disposal. There can be exceptions to it, which is why, as long as it is acceptable that in principle it is not impossible for the goal to be achieved by doing A, the critic can move on to the next questions. If it is not acceptable that it is in principle possible to achieve G by doing A, then a new conjecture is needed: the agent should go back to the starting point and, in light of his stated goal G, he should figure out another possible means.

One line of attack against austerity policies in the UK has challenged the means-goal premise. The critics have challenged the government’s belief in the possibility of achieving economic recovery by means of austerity. Bringing examples from the Great Depression and from Japan’s history of stagnation, they argued that, in general, by killing demand, austerity invariably fails to deliver the goals. According to these critics, some other means has to be sought and tested.

CQ2 Is it true (rationally acceptable) that the Agent is in circumstances C?

This amounts to asking whether the stated (or presupposed) circumstances (including the “problem”) are such as they are being represented. If the answer is negative, then the agent will be redirected to the starting point and will need to revise the description of the circumstances, then make a new conjecture about what action will resolve his problem. Critics of austerity have challenged the government’s representation of the current situation in Britain (as an economy “in ruins”, in a state of emergency similar to that of Greece) and its associated explanation. For example, they have denied that the crisis is one of excessive spending and the product of the Labour government’s profligacy, insisting that it was the banking sector that caused the crisis.

CQ3 Is it true (rationally acceptable) that the agent is actually motivated by stated goals/ values/concerns?

Normally, it is taken for granted that this is the case. But sometimes arguments are rationalizations: the stated (overt) reasons are not the real reasons; there are other (covert) reasons driving the proposed action (Audi 2006). For example, critics of the government have challenged the government’s alleged concern for “fairness”, or have argued that austerity policies are in fact ideology-driven (Krugman 2010), and that the real goal is to “complete the demolition job on welfare states that was started in the 1980s” (Elliott 2010).

If either of these three questions yields negative answers, then the decision-making process is redirected to its starting point and will have to start again, with (a) a different means-goal premise; (b) a more accurate representation of what the situation/problem is, or (c) another overt goal or normative concern – one that is not in contradiction with the facts available to the critic. These three possible loops back to the starting point are designed to ensure that, before the proposal itself is actually tested at the next stage, there has been adequate critical scrutiny of a number of assumptions: that the situation is as described, the goals and values are those that are overtly expressed, and the proposed means is at least in principle capable of delivering the goal. These first three questions do not yet aim to achieve a narrowing down of potential proposals.They cannot be ordered among themselves and are not part of the dialectical profile. Assuming there is intersubjective agreement on an affirmative answer to these three questions, critical testing of the proposal itself begins with CQ4.

The main stage in the critical testing process is the testing of the practical conclusion, i.e. the proposal to do A1 (or A2, … An), or the conjecture (hypothesis) that doing A1 (or A2, … An) is the right thing to do. This is done by examining the consequences of each proposal, based on all the information available. The following two questions, CQ4 and CQ5, should be asked for each conjecture A1 … An, and failure to answer them satisfactorily may indicate that the proposal ought to be abandoned:

CQ4 Are the intended consequences of A (i.e. the stated goal) acceptable?

CQ5 Are the foreseeable unintended consequences of doing A acceptable?If not, is there an acceptable Plan B, or some other form of redressive action available?

CQ4 asks whether the stated goal (the intended consequence) is acceptable, and CQ5 asks whether the unintended consequences (should they occur) are acceptable, as far as they can be foreseen, based on all the facts at the critic’s disposal. Ideally, “acceptability” is to be tested from all the relevant normative perspectives (e.g. rights, justice, consequences, other relevant concerns) and from the point of view of all the participants concerned. Not all relevant normative perspectives are equally important in each particular case, which is why a notion of ranking, of normative hierarchy is inherently involved at this point and the conclusion is typically arrived at “on balance”, after a process of deliberation. The following question-answer possibilities seem to exist:

CQ4 Are the intended consequences of A (i.e. the stated goals) acceptable?

No, (based on everything we know) the intended consequences are unacceptable à Abandon A.

A negative answer means that there are critical objections to A. Abandoning A can mean either doing nothing (refraining from action) or can lead to renewed deliberation about goals, i.e. going back to the starting point, so as to revise the goal and then make a new conjecture about what action will deliver this goal. The intended goal is unacceptable if, for example, it comes into conflict with other goals (of the agent or other relevant participants) or with deontic reasons that have normative priority (e.g. if the agent’s goal comes into conflict with someone’s else’s rights, and the latter emerge as non-overridable from a process of critical discussion).

The answer to CQ4 can also be affirmative:

Yes, (based on everything we know) the resulting state-of-affairs will be acceptable à accept A provisionally and proceed to CQ5.

The answer “yes” to this question means that there are no overriding reasons why the goal should not be realized. The proposal can be accepted provisionally and questioning can move on.

The next question (CQ5) inquires about the proposal’s potential unintended consequences. Proposals can be eliminated on account of unacceptable side effects if, based on all the facts or information available to the deliberating agents, it can be reasonably maintained, after a process of critical examination, that there is a risk that such-and-such effects may occur and that there is no way of handling that risk (see below) in a way that should enable the agent to proceed with doing A. If, based on all the information available, the answer to CQ5 is negative, then at least two possibilities exist:

No, based on everything we know, the unintended consequences are not acceptable à (a) abandon A, if unacceptable side effects constitute critical objections to doing A; (b) proceed with A tentatively, if there is a way of dealing with potentially unacceptable consequences, should they materialize.

Answer (a) means that there are objections against A that cannot be overridden, therefore the agent should abandon A, as it was originally conceived, go back to the starting point, choose a different conjecture and start the testing process all over again. For example, austerity policies have been deemed unacceptable because, even assuming the long-term stated goal to be acceptable, they were said to have unacceptable side effects, e.g. a dramatic reduction in employment possibilities for young people, or the risk of a “lost generation” (Blanchflower 2011).

Answer (b) means that the unintended consequences that might occur are in principle unacceptable but, in the context, they do not constitute critical objections to A. This could be for several reasons, all making implicit or explicit reference to a notion of strategy. For example, it could be that an effective way of dealing with the unintended consequences, should they actually arise, has been identified. There is, for example, a “Plan B” that the agent can switch over to at a later date (should emerging feedback be negative), which is why he can get on with doing A, assuming the negative consequences will not materialize (because, if they do, he will be able to change course). It is also possible that the agent is in some way “insured” against potential loss, so once again he can get on with the action and assume these losses will not happen. The agent can also get on with doing A if he can at the same time engage in a broader strategy of action, involving at least another parallel line of action, whose role is to mitigate the negative effects of doing A: while austerity creates unemployment, the government could simultaneously engage in a job-creation strategy for young people. It is also possible to reasonably persist in doing A in the face of emerging negative feedback if it can be reasonably argued that more time is needed before the intended consequences begin to appear (the situation “needs to get worse before getting better”). Finally, it is possible to answer CQ5 in the negative and, although no Plan B or other redressive action may exist, still decide to go ahead with A, thereby taking the risk of an unacceptable outcome. In such cases, although levels of “confidence” in a positive outcome (or in negligible levels of risk) may be high, there is a rationality deficit, and deciding to do A would be similar to a gamble.

The critics and defenders of austerity policies have exploited all these possibilities. Early in 2011, a fall in GDP for two consecutive quarters prompted the government’s critics to call explicitly for the adoption of a “Plan B”. The fact that the Chancellor was not willing to change course was taken as a failure of rationality, and as allegedly showing how power and vested interests were trumping the force of the better argument. It was also argued that the government’s strategy was inadequate in not taking measures to mitigate the impact of austerity by sufficiently stimulating various alternative sectors that could provide employment and growth – green industries, infrastructure projects. In their defence, the government denied that the side effects constituted critical objections, insisted that more time was needed for austerity to bear fruit, pointed to measures put in place to mitigate the impact of austerity on the poor, stressed the imperative of sticking to medium-term goals for the success of the overall strategy, and also claimed that the situation (the Labour “legacy”) was more serious than had been anticipated, hence the need for a reinterpretation of what would, on balance, constitute acceptable and unacceptable consequences.

The answer to CQ5 can also be affirmative:

Yes, (based on everything we know) the unintended consequences are acceptable à accept A provisionally and move on to CQ6.

A positive answer to CQ5 means that critical discussion has not found any critical objections, so A can be accepted provisionally (subject to future rebuttal) and questioning can move on. By contrast, a negative answer will redirect the deliberating agents to an antecedent stage of the testing process: they will either have to make a new proposal or revise the current one so as to avoid the unacceptable consequences, and then test these again, or abandon the proposal completely and refrain from action. They can only reasonably proceed with a proposal that could have unacceptable negative consequences if there is an effective form of redressive action available, some effective insurance or a way of changing course, should the negative consequences actually materialize.

So far, CQ4 and CQ5 have tested the practical conclusion and may have indicated that doing A is unreasonable. It is possible that not only one but several alternative proposals have survived criticism at this stage. Is there a way of choosing among them in a particular situation? This is where looking at the argument itself will be useful. The attempt will be to think of other relevant facts in the particular situation at issue, in light of which it may not follow that the agent ought to do A. One fact that can defeat the inference is the existence of other “better” means of achieving the goal (CQ6).

CQ6 Among reasonable alternatives, is A comparatively better in the context?

This judgment will involve various evaluative perspectives. If, for example, efficiency or cost-benefit analysis are relevant perspectives for an agent, then, if there are more efficient alternatives than A, or if there are alternatives which offer more benefits or fewer costs than A, then it does not follow that the agent ought to do A. But neither does it follow that the agent ought not to do A, unless some critical objection can be uncovered in the form of some unacceptable intended or unintended consequence.

At this stage in the dialectical profile, the question is one of choosing, among the reasonable alternatives that have emerged from CQ4 and CQ5, the one course of action that best corresponds to a particular agent’s de facto overriding concerns (value preferences). In the 2010 Emergency Budget, for example, Chancellor Osborne advocated a particular distribution of the financial consolidation: 80% of the savings were to come from spending cuts, while 20% from tax rises. It can be argued, even by defenders of austerity, that this ratio could have been slightly different, while still being reasonable from the government’s point of view. In the context, however, the 80:20 split was justified by a de facto concern to increase Britain’s attractiveness for business: it was a “better” alternative than other possible splits aimed at achieving the same total amount of savings.

If CQ4 and CQ5 can rebut the practical conclusion, CQ6 can defeat the inference from the premises to the conclusion. While failure to provide a satisfactory answer to CQ4 and CQ5 may indicate that the agent ought not to do A, failure to do so in the case of CQ6 will not indicate that the agent ought not to do A (i.e. that doing A is unreasonable, seeing as no unacceptable consequences have been revealed by either CQ4 or CQ5), but merely that the argument is defeated in the context, once one or more relevant premises are added to the premise set.

Conclusion

The most important questions in the set above (CQ4 and CQ6) are aimed at testing the practical conclusion by examining its consequences (thus trying to find critical objections against doing A). A practical argument is not evaluated only in terms of the instrumental adequacy of proposed means to pre-given goals. The goals themselves, as intended consequences of action, should be challenged and, if found unacceptable, the deliberative process should start again, with a new goal. Questions CQ4-CQ6 can achieve a progressive narrowing down of possibilities for action: proposals are tested in light of their consequences and eliminated if these consequences are on balance unacceptable; a principled choice amongs several reasonable proposals is also possible, in light of various contextually-relevant evaluative perspectives. The dialectical profile (CQ4-CQ6) I have suggested – as well as the wider set of questions (CQ1-CQ6) of which it is a part –integrate deliberation about means and deliberation about goals within a recursive procedure, which includes, at every stage, a loop back to the starting point or to some antecedent stage. A notion of normative priority enables the elimination of unreasonable alternatives (those that the agent ought not to choose, i.e. those whose consequences would be on balance unacceptable), while a notion of de facto priority (based on contextual value preferences) can subsequently select one better alternative among a set of reasonable alternatives.

The deliberation scheme and its attached set of critical questions connect two argument schemes, showing how an argument from negative consequence is used in deliberative activity types to test the practical conclusion of an argument from goals and circumstances. It thus hopes to reflect more adequately decision-making as a process governed by bounded rationality. Critical testing is not, even ideally, aimed at discovering the “best” solution, but at “weeding out” the unreasonable solutions and thus narrowing down a set of options. Having done that, it may move on to identifying a subset of comparatively better solutions amongst those reasonable alternatives.

The profile also integrates considerations of uncertainty and risk. This makes it a more realistic picture of how people act. Agents are almost always willing to allow action to proceed even in conditions of uncertainty and risk. They will not necessarily discard a proposal that could have serious negative consequences but will try to tailor their action in such a way as to allow them to make piecemeal adjustments and revisions, should those potential unacceptable consequences materialize. Often, however, they will take the risk of acting even when no such possibilities of redressive action exist.

REFERENCES

Audi, R. (2006). Practical Reasoning and Ethical Decision. London: Routledge.

Blanchflower, D. (2011, February 17). The scars of a jobless generation, New Statesman. Retrieved from http://www.newstatesman.com/economy/2011/02/youth-unemployment-labour.

Eemeren, F.H., van & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation. The Pragma-Dialectical Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F.H., van (2010). Strategic Maneuvering in Argumentative Discourse, Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Elliott, L. (2010, June 14). The lunatics are back in charge of the economy and they want cuts, cuts, cuts. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/jun/14/lunatics-economy-cuts-frankin-roosevelt.

Fairclough, I. & Fairclough, N. (2011). Practical reasoning in political discourse: the UK government’s response to the economic crisis in the 2008 Pre-Budget Report. Discourse & Society, 22(3), 243-268.

Fairclough, I. & Fairclough, N. (2012). Political Discourse Analysis: A Method for Advanced Students. London: Routledge.

Fairclough, I. & Fairclough, N. (2013). Argument, deliberation, dialectic and the nature of the political: A CDA perspective. Political Studies Review, 11(3), 336-344.

Fairclough, I. (2015). Evaluating policy as argument: the public debate over the first UK austerity budget. Critical Discourse Studies, DOI: 10.1080/17405904.2015.1074595.

Garssen, B. (2001) Argument schemes, in F.H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Crucial Concepts in Argumentation Theory (pp. 81-100). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Garssen, B. (2013). Strategic maneuvering in European parliamentary debate, Journal of Argumentation in Context, 2(1), 33-46.

Hitchcock, D. (2002). Pollock on practical reasoning, Informal Logic, 22(3), 247-256.

Hitchcock, D., McBurney, P., & Parsons, S. (2001). A framework for deliberation dialogues. In H.V. Hansen, C.W Tindale, J.A. Blair, & R.H Johnson (Eds.), Argument and Its Applications: Proceedings of the Fourth Biennial Conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (OSSA 2001).

Ihnen Jory, C. (2012). Pragmatic Argumentation in Law-making Debates: Instruments for the Analysis and Evaluation of Pragmatic Argumentation at the Second Reading of the British Parliament, Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books.

Krugman, P. (2010, October 21). British fashion victims. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/22/opinion/22krugman.html.

Miller, D. (1994). Critical Rationalism: A Restatement and Defence. Chicago: Open Court.

Miller, D. (2005). Do we reason when we think we reason, or do we think? Learning for Democracy, 1(3), 57-71.

Miller, D. (2006). Out of Error. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Miller, D. (forthcoming). Deductivist decision making, unpublished MS.

Osborne, G. (2010). 2010 Budget – Responsibility, freedom, fairness: a five year plan to re-build the economy. HM Treasury. Retrieved from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130129110402/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/2010_june_budget.htm.

Searle, J. R. (2010). Making the Social World. The Structure of Human Civilization, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioural model of rational choice, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69, 99-118.

Walton, D. (2006). Fundamentals of Critical Argumentation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Walton, D. (2007a). Media Argumentation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Walton, D. (2007b). Evaluating practical reasoning. Synthese, 157, 197-240.

Walton, D., Reed, C. & Macagno, F. (2008). Argumentation Schemes. New York: Cambridge University Press.