ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ Verbs Of Appearance And Argument Schemes: Italian Sembrare As An Argumentative Indicator

Abstract: This paper investigates the role of verbs of appearance as argumentative indicators analysing the uses of the Italian verb sembrare (‘seem’) in a sample of 40 texts chosen from a corpus of reviews, editorials and comment posts. An analysis conducted within the framework of the Argumentum Model of Topics, shows that the verb, in its evidential-inferential uses, indicates specific argument schemes of the symptomatic as well as the causal type.

Keywords: argumentative indicators, Argumentum Model of Topics, causal argumentation, inferential evidentiality, Pragma-Dialectics, symptomatic argumentation, syntagmatic argument schemes, verbs of appearance

1. Introduction

This paper addresses the relations between verbs of appearance and argument schemes, taking as an example the Italian verb sembrare (‘to seem’) in its function as an argumentative indicator[i]. In the framework of Pragma-Dialectics, the notion of argumentative indicators has been defined as including “all words and expressions that refer to any of the moves that are significant to the argumentation process” (van Eemeren, Houtlosser & Snoeck Henkemans, 2007, p. 2). Such argumentative clues can belong to different classes of linguistic items, ranging from verbs to conjunctions and to various kinds of discourse markers[ii]. Within Pragma-Dialectics, argumentative indicators have been considered, above all, from the point of view of the analyst facing the task of argumentative reconstruction. In this perspective, it has been underlined that indicators may work at different levels, signaling, for example, the engagement of the interactants in a particular stage of a critical discussion[iii], argumentative moves or the presence of a particular argumentation scheme. From a linguistic point of view, it is crucial to acknowledge that the usefulness of indicators for the analyst depends on their usefulness for the participants engaged in an argumentative interaction. Like other aspects of textual or conversational structure, the construction of argumentative relations at the different levels mentioned above is, in the first place, the participants’ task; functional categories are emic, not etic (Pike 1954). What justifies the attribution of an indicator function to a linguistic expression is, then, the potential of the expression to guide interlocutors and readers in this task. In any particular context, this potential will depend both on the expression’s functions coded in a relatively stable manner in the linguistic system (e.g. in the lexicon or in the domain of recurrent syntactic constructions and discourse routines) and on the specific pragmatic configuration (Bazzanella & Miecznikowski 2009) the expression is used in. As we will argue in our paper, corpus-based linguistic analysis, focused on single expressions and their contexts of occurrence, can fruitfully contribute to a better understanding of argumentative indicators in this sense.

Like other verbs of appearance interlinguistically (e.g. English to seem, Spanish parecer), the verb sembrare has been attributed an evidential function in the linguistic literature when occurring in certain syntactic and pragmatic contexts[iv]. Evidentials specify “the kind of justification for a factual claim which is available to the person making that claim […]” (Anderson, 1986, p. 274). The typological analysis of evidential systems has shown that frequently grammaticalized types of justifications for assertions, otherwise called information sources, means/ways of acquiring knowledge or modes of knowing, are direct experience (eventually distinguished according to perceptual modality), inference, and report/hearsay (cf. Willett 1988). Research on lexical evidentials (e.g. Squartini 2007) suggests that these cognitive categories are relevant also in linguistic systems that do not grammaticalize evidentiality, and it is in this line of thinking that the notion of evidentiality is currently used to analyze the semantics of appearance verbs.

Evidentiality and argumentation are related because the justification of claims is, of course, the defining feature of one of the central moves in argumentative discourse. However, an important difference between evidentially marked utterances and full-fledged argumentative moves is that, in the former case, the speaker signals the presence of evidence in favor of his or her assertion and categorizes that evidence in a generic fashion, whereas in the latter case, the speaker establishes a discourse relation between the assertion and one or more specific arguments given in the text. By consequence, speakers can use evidentials both to support argumentation, contributing to establish argument-conclusion relations present in a critical discussion, and as an alternative to argumentation, merely suggesting the relevance of evidence without actually formulating any arguments. Recent studies at the semantic-argumentative interface (Miecznikowski, 2011; Rocci, 2008, 2012, 2013) have concentrated on the argumentation supporting function of modal and evidential expressions, arguing that, in argumentative contexts, these expressions function as indicators strengthening and categorizing argument-conclusion relations. One of the basic ideas is that the evidential categorization of modes of knowing in an utterance restricts the range of argument schemes with which the utterance is compatible. In the present analysis, we will develop this idea, showing that sembrare constructions preferentially occur with certain argument schemes and insisting in the role of the verb’s lexical meaning at this regard. Argument schemes will be analyzed and reconstructed using the Argumentum Model of Topics (Rigotti & Greco Morasso 2010).

In section 3, after having presented our data, we will provide an overview of the syntactic constructions of sembrare associated with evidential meanings and explain why these constructions are good candidates to function as argumentative indicators. We will then focus on sembrare as an indicator of argument schemes. We will discuss existing research on copulative constructions with appearance verbs as indicators of argument schemes (section 4), before presenting the results of our corpus study (section 5).

2. Data

The data considered in this paper consist of 40 texts taken from a mixed corpus of reviews, editorials and posts published in the comment spaces associated with reviews and editorials.[v]. The texts in our corpus have been collected from the Italian daily newspapers La Stampa and La Repubblica and from four thematic websites about art exhibitions (www.mostreinmostra.it), music (www.fullsong.it), haute cuisine (www.passionegourmet.it) and consumer electronics (www.digital.it).

The choice of these text genres is motivated by the important role argumentation plays in them and by the variety of activity fields they cover. In editorials, journalists express an opinion, mostly on a political matter, backing it up by arguments. In reviews, experts or consumers evaluate an object on the basis of firsthand experience as well as field-specific knowledge and values (Miecznikowski, in press). Comment spaces allow for a lot of variation in terms of text genres. Argumentation is common in most types of posts, however. On one hand, users react to the standpoints and arguments put forward in the text they comment on; on the other hand, on the metacommunicative level, users formulate opinions about the text as such, usually backing up their judgment by at least one argument[vi].

3. Sembrare constructions

The verb sembrare semantically presupposes two participants, namely an experiencer and an experienced. The experience in question can be entirely mental or involve perception.

The mental/perceptual process undergone by the experiencer is expressed by various syntactic constructions in which the experiencer role is either expressed by an indirect object NP or left implicit. The main form-function patterns attested with sembrare are the following:

I. Copula constructions asserting similarity between two elements (a, b), the first having a set of properties identical to a set of properties of another individual:

1. [Marco]a sembra [suo padre]b .

‘Marco looks like his father’.

II. Copula constructions and infinitive constructions asserting the existence of clues to attribute a property B to an individual a and warranting the implicature, under certain circumstances, that the speaker indeed attributes B to a:

2. [Marco]a (mi) sembra [affamato/aver fame]B .

‘Marco seems hungry/to be hungry (to me)’.

In (2), the speaker states that Marco has a set of (unspecified) properties that normally warrant the attribution of the property ‘to be hungry’. Without contextual clues to the contrary, the hearer may infer that the experiencer (here: the speaker) holds the weak belief that Marco is hungry.

III. Constructions with a complement clause in subject function. These directly and explicitly attribute a belief to the experiencer, presupposing that this belief is based on available evidence:

3. (Mi) sembra [che Marco sia stanco]p.

‘It seems (to me) that Marco is tired’.

In type I contexts, the experiencer usually coincides with the speaker and is left implicit. The experience encoded by sembrare is that of grasping the results of a process of comparison and the verb does not have an evidential function in this construction[vii].

In contexts of the types II and III sembrare can fulfill evidential functions under two conditions. The first condition is that the experiencer hold the (albeit weak) belief p. This depends on context in II, whereas the experiencer’s holding a belief is encoded grammatically in III, where the complement clause strongly suggests the presence of a proposition, i.e. of a third order entity that can be attributed a truth value and thus become a term of a belief relation[viii] When this condition is fulfilled, sembrare denotes a complex situation in which someone holds a belief on the basis of some available evidence. The second condition is that the experiencer coincide with the speaker and that the experience take place in the moment of speech. In that case, exemplified by (2) and (3) above, the verb has a performative character (Faller 2002), i.e. knowledge acquisition is not reported, but presented as achieved in the moment of speech, and the relation between p and the available evidence is mapped onto the ongoing speech event.

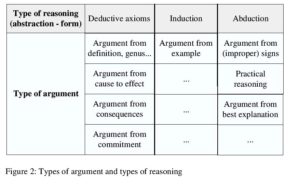

When sembrare is used evidentially, it always signals an indirect mode of knowing, i.e. either inference or hearsay/report. In this paper, we will be concerned especially with the verb’s inferential uses. Example (2) above is a typical case: if the speaker holds the belief that Marco is hungry, this belief is based on a reasoning process that takes into account a set of Marco’s properties in combination with further, more general, premises. In what follows, we will take a closer look at the type of reasoning sembrare is compatible with.

4. Symptomatic argumentation

In the pragma-dialectic approach, three main types of argument schemes are distinguished, namely those based on a symptomatic relation, those based on a relation of analogy and those based on a causal relation (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992, pp. 98-99). In symptomatic argumentation, the argument (minor premise) and the standpoint have a common referent (X) but different predicates, as visualized in the scheme:

Y is true of X

Because Z is true of X

ANDZ is typical (characteristic/symptomatic) of Y

(van Eemeren and Grootendorst, 1992, p. 98)

The property attributed to ‘X’ in the minor premise is a symptom of the property ascribed to it in the standpoint. The major premise states the association between entities or situations which justifies the relation between the argument and the standpoint. The critical questions underlying symptomatic argumentation are the following:

– Is Z indeed typical of Y?

– Is Z not also typical of somethingelse (Y’)?

(van Eemeren and Grootendorst, 1992, p. 99)

According to Garssen (1997, p. 77-101) the category of symptomatic argumentation encompasses different subtypes of arguments such as those based on a classification, on genus-species relations, on definition and on evaluation critieria.

Van Eemeren, Houtlosser & Snoeck Henkemans (2007, p. 160) identify copulative constructions in which the predicative is an adjective or noun containing the copula to be, or its modal variants to seem/appear, as particularly suitable to form the standpoint or the minor premise in a symptomatic argumentation. According to these scholars, the abovementioned copulative constructions are good candidates to signal symptomatic argumentation because the copula normally refers to states rather than to events or processes, mirroring the nature of symptomatic argumentation, which is about qualities and features rather than about events or processes.

In analogy with van Eemeren’s, Houtlosser’s & Snoeck Henkemans’ (2007) proposal, also Italian sembrare can be hypothesized to be associated with symptomatic argument schemes. Lexical semantic arguments lend further support to this hypothesis. One of the core elements of the meaning of sembrare is the idea of similarity. This idea is present not only in the type I contexts discussed in the previous section, but also in inferential uses. In the type II contexts, in particular, the identification of clues to the presence of a property B often relies on a process of categorization by which a specific individual or situation is matched to a category (proto)type:

(4) Sembra una beffa la conclusione del processo Mills-Berlusconi. Dopo anni di preparazione, mesi di udienze, non abbiamo neanche un verdetto sulla colpevolezza o meno dell’ex premier Berlusconi.

‘The conclusion of the Berlusconi Mills’ trial seems a farce. After years of preparation, months of hearings, we do not even have a verdict on the guiltiness or innocence of the former Prime Minister Berlusconi’.

(La Repubblica, editorial, February 2012)

In example (4), the speaker categorizes a trial as a farce. One plausible reconstruction of this process of categorization is that the author compares what he has observed to his idea of typical farces:

The conclusion of the Mills’Berlusconi trial seems a farce

Because after months of preparation the trial has not produced a verdict (i.e. no goal has been reached and, by consequent, the participants’ acts appears to be meaningless) (and it is typical of farces that one cannot recognize any sense in people’s acting).

The schema of similarity activated by sembrare fosters the establishment of a link between the minor premise, in which a property is attributed to the first term of comparison, and the major premise, in which the same property is recognized as being typical of the classes of farces.

5. Sembrare and argument schemes in editorials, reviews and comments

5.1 Analytical approach

Sembrare occurs 52 times in our corpus. 39 occurrences are performative; among these, 2 are of type I construction, 17 of type II and 20 of type III. In order to find out which are the argument schemes compatible with sembrare, we have analyzed the local co- and context of all tokens in order to determine plausible implicit premises and have reconstructed the inferential relations applying the Argumentum Model of Topics (Rigotti, 2006, Rigotti, 2009a, Rigotti & Greco-Morasso, 2010).

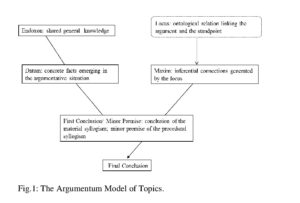

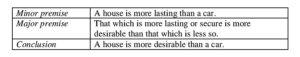

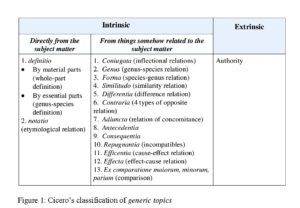

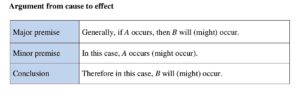

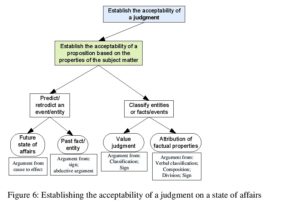

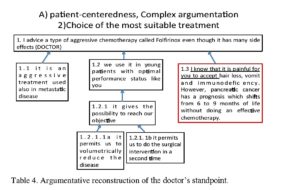

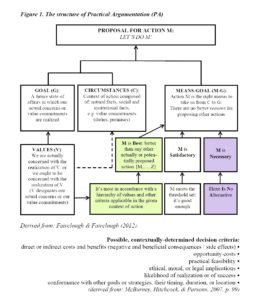

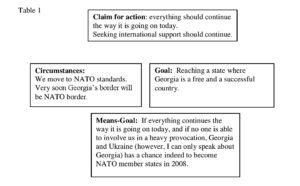

Compared to the pragma-dialectical approach to argument schemes illustrated in the preceding section, AMT allows for a more detailed analysis of implicit premises. According to AMT, the inferential structure of any argumentation presupposes the presence of both procedural and material premises. Procedural premises have the form of maxims that define the inferential connections at issue. They are based on loci, pieces of an ontology shared by the speech community which “bind the truth value of the standpoint to the acceptance by the considered public of propositions referring to specified aspects of the ontology of the standpoint” (Rigotti, 2006, p. 527). Material premises are of two types: the endoxon, a major premise that refers to shared general knowledge and is often left implicit, and the datum, a factual (minor) premise that is often (but not necessarily) made explicit. In order to generate relevant arguments, as represented in the schema in fig. 1, procedural and material components must be combined in a double syllogistic structure (Fig.1):

5.2 Sembrare as an indicator of symptomatic argumentation

Our data confirm the role of sembrare as an indicator of symptomatic relations. The verb is indeed compatible with symptomatic argumentation in each of its constructions. More specifically, the attested subtypes of argument schemes exploit ontological relations from definition, from the parts to the whole, from implications and from concomitances.

To illustrate this group of argument schemes, we will reconstruct an example taken from an editorial of the Italian daily newspaper La Stampa about a speech in support of democracy as a prerequisite for peace, which Pope Wojtyła delivered in occasion of the disorders in Iraq during 2003:

(5) Dunque siamo grati dal profondo del cuore a Giovanni Paolo II per la costanza e la determinazione con cui ha levato la voce (una voce anche fisicamente piu’ alta e chiara, sembra che stia assai meglio ed è questo un altro motivo di consolazione).

‘Therefore we are deeply grateful to John Paul II for the persistence and the determinacy with which he has raised his voice (a voice also physically louder and clearer, it seems that he is in much better health and this comforts us even more).’

(La Stampa, editorial, April 2003)

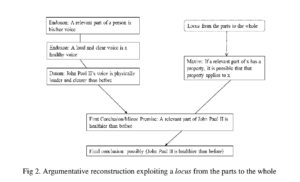

In (5), the verb sembrare indicates that that the speaker is committed to the proposition ‘John Paul II is in much better health’ on the basis of the fact that the Pope’s voice is louder and clearer than before. This piece of evidence is a datum made explicit in the text. As to the ontological relationship between a loud voice and a state of good health, it can be conceptualized in different manners. The example might be analyzed as an instance of reasoning from the effect to the cause, if we view a loud voice as a result of the proper functioning of a healthy organism. Alternatively, it could be hypothesized that good health and a loud and clear voice are properties that are frequently associated in the experience of the speaker and the hearer, giving rise to argumentation by concomitance.

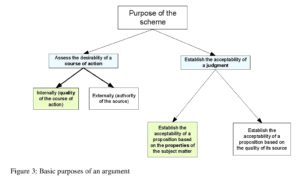

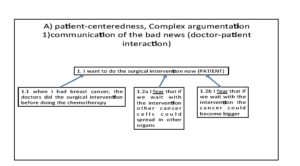

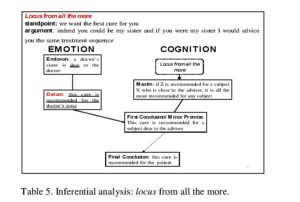

Yet another solution could be proposed, in virtue of the fact that the journalist, in this text, has chosen to institute John Paul’s voice as a discourse referent and to attribute a property to it. The journalist seems to underline the object-like status of the Pope’s voice, rather than the event of the Pope using his voice. For this reason, a part-whole relationship might be relevant in this example. If we assume that the voice is a relevant part of a person and that loudness and clearness are synonyms of healthiness when applied to a voice, the property of healthiness can be transferred from the voice to the entire person, through a maxim like the one proposed in the following reconstruction (Fig. 2):

The validity of the transfer is, of course, questionable. As underlined by van Eemeren & Garssen (2009), only absolute structure-dependent properties, such as those expressing colours or materials, are always transferrable. The choice of sembrare, which signals weak commitment, is congruent with such a context.

5.4. Sembrare as an indicator of causal argumentation

As we have seen discussing the preceding example, symptomatic argumentation does not exclude causal schemes (from the effect to the cause). In a number of contexts, however, causality – be it from the effect to the cause or from the final cause (Rigotti 2009b) – is even the most prominent ontological relation warranting the inferential transition from argument to conclusion. We have found cases of this type mostly in contexts in which speakers refer to the field of human action. In this use of sembrare, the preferred syntactic construction in the corpus is the complement clause construction.

The example we propose is taken from a post published on the website of the Italian daily newspaper La Repubblica, which comments on an editorial about Silvio Berlusconi’s defeat in the 2011 elections:

(6) La saga SB [Silvio Berlusconi] è stata una tragedia italiana che ha fatto rivivere atteggiamenti machisti ed incolti che ci hanno riportato indietro di decenni quando il nostro Paese nuotava ancora nell’analfabetismo e le nonne si stupivano della nuova invenzione della televisione. Fortunatamente sembra che il Paese sia uscito dallo stato ipnotico in cui i vari programmi televisivi lo avevano affogato.

‘The saga of SB [Silvio Berlusconi] has been a tragedy characterized by a revival of machism and uncultivated attitudes that have taken us decades back, when our country was still swimming in illiteracy and grandmothers were amazed in front of the new invention of television. Luckily, it seems that the country has woken up from the hypnotic state in which the various television programs had drowned it.’

(La Repubblica, post commenting on an editorial, June 2011)

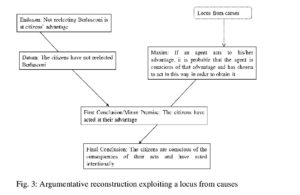

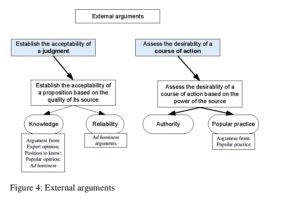

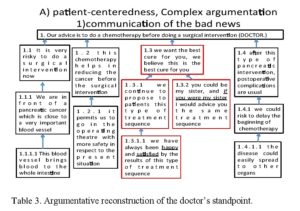

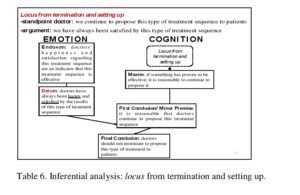

The author claims that the country has got out of ‘the hypnotic state in which the various television programs had drowned it’. The arguments supporting this claim are largely left implicit, which is related to the highly interactive and inter-textual situation typical of forum discussions. In order to reconstruct the writer’s argumentation, we have supplied the missing premises on the basis of linguistic and contextual clues and we have interpreted the metaphorical expression “getting out of an hypnotic state”, hypothesizing that the author intends to stress the citizens’ regaining consciousness and agency (Fig. 3):

The fact that citizens have not reelected Berlusconi is highly salient in this comment space and can therefore function as a datum although it is not mentioned. The presence of the adverb ‘luckily’ in the standpoint as well as the claim that the country was in a state of backwardness due to Berlusconi’s government show that the author considers Berlusconi’s defeat as an advantage for the Italian people, an opinion that emerges also in other parts of the text. Considering La Repubblica’s political orientation, the author can assume that many readers share this opinion as an endoxon. The maxim at work is causal and is part of an ontology of human action (agents normally act in such a way as to obtain results that are advantageous for them), making it possible to reconstruct the pragmatic reasoning of agents. As a result, a certain state of mind of agents is infered from these agents’ deeds. Like in (5), the reasoning is defeasible, due to the defeasibility of the maxim (agents may act without being fully aware of their acts’ consequences).

5.5. Discussion

The data we have examined shows that sembrare can indicate symptomatic argumentation in any of its constructions, while it tends to be associated to causal relations only in the most pragmaticalized one (the one in which it functions most clearly as a propositional operator, rather than as a predicate attributed to a specific subject). The semantic relationship between causal reasoning and the lexical meaning feature /similarity/ is also rather weak. Both observations lead to the hypothesis that the possibility to express causal reasoning might be mediated by the dominant evidential function of the complement clause construction, which shifts language users’ attention from the lexeme’s core meaning to the pragmatic operation of indicating an indirect mode of knowing.

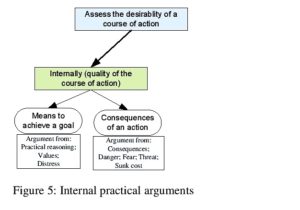

Nevertheless, that functional generalization is not complete. Even in complement clause constructions, sembrare is not compatible with any argument scheme, and symptomatic and causal arguments share some relevant features. One of these is that the various argument schemes of this group are based on loci that we can define “syntagmatic”, following Rigotti (2006):

we speak of syntagmatic loci to indicate all the classes of arguments that refer to aspects that are ontologically linked to the standpoint, either directly or indirectly, such as[..] the relationship between the whole and its constituent parts; included in this group of loci are also the classes of arguments which assume as their hooking point those pieces of world, traditionally called causes, effects, circumstances and concomitances, that condition the state of affairs the standpoint refers to.

(Rigotti, 2006, p. 528)

The term syntagmatic loci has been adopted in the AMT framework (e.g. Rigotti, 2007) to oppose these to the paradigmatic ones, in which the argument and the standpoint refer to ontologically independent states of affairs and are rather linked by relations in absentia such as opposition or analogy. The AMT model distinguishes, moreover, the intermediate class of complex loci encompassing those cases which present features of both syntagmatic and paradigmatic argument schemes. A typical example of a complex locus is the locus from authority, which establishes a causal relation between the qualities of an author and the truth of his or her discourse, while there is no direct ontological relation between the state of affairs referred to in the standpoint and the communicative situation in which the authoritative discourse is uttered.[ix]

Sembrare appears to be compatible with syntagmatic loci and, in the hearsay reading of the complement clause construction, with the complex locus of authority as well (e.g. A quanto dicono, sembra che la sinistra vincerà le elezioni, ‘According to what they say, the right wing will win the elections’).

Another restriction, which regards causality, is that sembrare is not equally compatible with any causal argument scheme. We have found several instances of argumentation from the effect to the cause, but none from the cause to the effect, neither in inferences concerning the past or present nor in predictions. The following set of constructed examples illustrates this tendency. Whereas the conclusion introduced by sembra in (7a) can easily be derived from the premise expressed in the preceding statement, this is not the case in (7b), where sembra (in contrast to other solutions such as deve ‘must’) is acceptable only if additional perceptual or hearsay evidence is assumed to be available in the context:

(7a) Marco ha una faccia stanchissima. Sembra che abbia fatto tardi ieri sera .

‘Marco has a very tired face. It seems he went to bed late, yesterday night.’

(7b) ?Marco ha fatto tardi ieri sera. Sembra che sia stanchissimo. [perceptual or hearsay evidence required].

‘?Marco went to bed late yesterday night. It seems that he is really tired’.

In predictions, inferential sembrare seems to be less acceptable with the future tense than when it is combined with a periphrasis such as stare per, which indicates a phase immediately prior to an event, or with alethic dovere ‘must’ with future reference, which indicates a situation that will cause an event:

(8a) (Mi) sembra che stia per/debba cadere. ‘

(To me), it looks as if he/she/it is about to fall.’

(8b)?(Mi) sembra che cadrà. ‘

(To me), it looks as if he/she/it will fall.’

A possible explanation of these patterns is a temporal one: by choosing inferential sembrare speakers typically signal that the available datum allows to infer a simultaneous state of affairs. This is compatible with the basic scheme of symptomatic argumentation (cf. section 4) and is evident in the cases illustrated by the examples (1) to (5) discussed in previous sections; but this analysis applies also to (a). The extension to causal inferences about the past illustrated by (6) and (7) could be mediated by the passato prossimo, since one of the functions of this tense is to denote a resultant state. The resultant state is, by the way, communicatively highly relevant in our example (6). We are aware of apparent exceptions to this generalization such as the use of sembrare in weather forecasts or with the passato remoto:

(9) (observing the sky): Sembra che pioverà.

‘It seems it will rain.’

(10) Mi sembra che il centro commerciale fu costruito negli anni ’70.

‘As far as I know, the shopping mall was built in the Seventies’.

However, these examples may be considered instances of mixed loci that share less properties with inferential uses of sembrare than with the verb’s hearsay uses, which, according to our data, are not subject to any temporal restriction. In (10), a context type that is not attested in our corpus, the knowledge source is recall from memory, whereas (9), for cultural reasons, may be framed as a semiotic practice of sign reading rather than being an instance of genuine causal reasoning[x]. Further research on appearance verbs expressing inferences about the past and the future is needed to corroborate this hypothesis.

6. Conclusion

The empirical study presented in this paper has shown that evidential uses of Italian sembrare can be used to introduce a standpoint and that they constrain the set of relevant argument schemes. The lexical meaning of sembrare makes this verb compatible with symptomatic as well as certain causal argument schemes which may be subsumed under the wider category of syntagmatic or mixed argument schemes. According to a hypothesis that has to be checked against a larger and more varied set of data, inferential uses (a) show a preference to express a temporal relation of simultaneity between the datum and the conclusion, which (b) can be extended to reasonings about non simultaneous causes and effects, especially when the verb is combined with temporal and modal markers that encode a posteriority or anteriority relation between an event and a state[xi].

Lexical semantic analysis, syntactic analysis and the argumentative reconstruction of texts are all necessary to understand which inferential processes are encoded by evidential constructions and to define their function as argumentative indicators in discourse. Perception and appearance verbs combine epistemic stance marking and evidential meanings and often occur in contexts in which the justifications at the basis of the uttered proposition are left implicit. Their polysemy and dependance on syntactic constructions calls for a fine-grained, context-sensitive semantic analysis.

The investigation of evidential and modal verbs usefully completes the growing body of research on discourse markers as argumentative indicators. Discourse markers, for example conclusion introducing connectives or concessive markers are useful to the analyst to recognize stance and argumentative moves, while evidentials and modals appear to be particularly relevant to argumentative analysis with regard to stancetaking and argument schemes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participant to the 8th Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (ISSA) for their very helpful comments and suggestions.

NOTES

i. The study presented is part of a research on the relationship between inferential uses of perception verbs and argumentation conducted at the Università della Svizzera italiana (“From perception to inference. Evidential, argumentative and textual aspects of perception predicates in Italian”, SNF grant n.141350, direction: Johanna Miecznikowski and Andrea Rocci, cf. http://www.perc-inferenza.ch).

ii. Discourse markers are particles, connectives, sentence adverbs or more complex lexical expressions that do not contribute to the propositional content of their host utterance, are syntactically poorly integrated and whose primary function is to relate utterances to their co- and context at the textual, inferential or interactional level. See Bazzanella (2006) for a more detailed discussion of the category and Miecznikowski et al., 2009, for a corpus based analysis focussed on argumentative functions of the discourse connective allora in Italian.

iii. According to the Pragma-Dialectical framework (e.g. van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992), argumentation takes place within the context of a critical discussion involving protagonists and antagonists that critically test standpoints in order to reduce a difference of opinion. According to that model, the subtasks, or stages, defining a critical discussion are the confrontation stage (a difference of opinion is made explicit), the opening stage (the interactants commit themselves to resolve the difference of opinion and agree upon some basic assumptions and rules), the argumentation stage (arguments are put forward to justify or refute standpoints), and the concluding stage.

iv. Appearance verbs and evidential uses of perception verbs have been studied in Romance and Germanic languages by Usoniene, 2001, Pietrandrea, 2005, Cornillie, 2007, 2009, Aijmer, 2009, Diewald & Smirnova, 2010, Strik Lievers, 2012, Musi, in press a, b. For a diachronic perspective cf. Gisborne & Holmes, 2007 and Whitt, 2011 on English and Musi, 2014 on Italian sembrare.

v. The corpus has been compiled within the project From perception to inference. We would like to thank Martina Cameroni, Giuliana Di Febo and Francesca Saltamacchia for their contribution to data collection.

vi. See Miecznikowski & Musi (submitted), who adopt a genre perspective to investigate the relationship between reviews published online and the posts published in the corresponding comment spaces.

vii. The process of comparison is presupposed by the propositional content of p (similarity), whereas evidential operators are independent of the content of the proposition in their scope. In fact, in (1), the speaker commits herself to asserting the results of the comparison process, leaving the mode of knowing proper unspecified: (1) is both compatible with a situation in which the speaker has seen how Marco and Marco’s father look and infers the similarity relation on that basis, and with a situation in which the speaker has come to know about the resemblance between father and son by hearsay.

viii. According to Lyons’ classification of ontological entities (1977, pp. 438-452), taken up also in Functional Discourse Grammar (Dik, 1997), propositions are third order entities which can be judged in terms of truth value, whereas (differently from second order entities, i.e. states of affairs) they cannot be located in space and time.

ix. Cicero proposes, in his Topica (see Riposati, 1947, pp. 34-35), a distinction between intrinsic loci (alii in eo ipso de quo agitur haerent, ‘some [loci] are linked to the subject of the discussion’), and extrinsic loci (alii assumuntur extrinsecus, ‘other [loci] are derived from outside’). This topical taxonomy has been further elaborated by Boethius in his De Topiciis Differentiis (see Stump, 2004), who also suggests a third category of loci medii situated between the intrinsic and the extrinsic loci.

x. It may be relevant, at this regard, that Italian modal verbs behave atypically as well in meteorological contexts, as shows the use of deve in Deve piovere ‘it will rain’, discussed by Squartini, 2004 and Rocci, 2013:143.

xi. As far as future reference is concerned, the role played by lexical and modal verbs implying posteriority relations has been examined by Miecznikowski, under review, on the basis of an Italian corpus of economic predictions.

References

Toulmin, S. E. (1958). The uses of argument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Benoit, W. L. (1989). Attorney argumentation and Supreme Court opinions. Argumentation and Advocacy, 26, 22-38.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1993b). The history of the argumentum ad hominem since the seventeenth century. In E. C. W. Krabbe, R. J. Dalitz & P. A. Smit (Eds.), Empirical Logic and Public Debate. Essays in Honour of Else M. Barth (pp. 49-68). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Aijmer, K. (2009). Seem and evidentiality. Functions of Language, 16 (1), 63-88.

Anderson, L. B. (1986). Evidentials, paths of change, and mental maps: Typologically regular asymmetries. In W. Chafe & J. Nichols (Eds.), Evidentiality: The linguistic coding of epistemology (pp. 273-312). Norwood (NJ): Ablex.

Bazzanella, C. (2006). Discourse markers in Italian: towards a ‘compositional’ meaning. In K. Fischer (Ed.), Approaches to discourse particles (pp. 449-464). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bazzanella, C., & Miecznikowski, J. (2009). Central/peripheral functions of allora and ‘overall pragmatic configuration’. In M. B. Mosegaard Hansen & J. Visconti (Eds.), Current Trends in Diachronic Semantics and Pragmatics (pp. 107-121). Oxford: Emerald.

Cornillie, B. (2007). Evidentiality and Epistemic Modality in Spanish (Semi-)Auxiliaries: A Cognitive-Functional Approach. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Cornillie, B. (2009). Evidentiality and Epistemic Modality: On the Close Relationship between Two Different Categories. Functions of Language, 16 (1), 44-62.

Diewald, G. & Smirnova, E. (2010). Evidentiality in German: Linguistic Realization and Regularities in Grammaticalization. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Dik, S. (1997). The Theory of Functional Grammar. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication and fallacies. A pragma-dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Houtlosser, P., & Snoeck Henkemans, F. (2007). Argumentative indicators in Discourse. A Pragma-Dialectical Study. Amsterdam: Springer.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Garssen, B. (2009). The fallacies of composition and division revisited. Cogency, 1(1), 23-42.

Faller, M.T. (2002). Semantics and pragmatics of evidentials in Cuzco Quechua, PhD Thesis Stanford.

University, Stanford. Garssen, B. (1997). Argumentatieschema’s in pragma-dialectisch perspectif. Een theoretisch en empirisch onderzoek. Amsterdam: IFOTT.

Gisborne, N. & Holmes, J. 2007. A History of English Evidential Verbs of Appearance. English Language and Linguistics, 11 (1),1-29.

Lyons, J. (1977). Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miecznikowski J., Gili Fivela, B., Bazzanella C. (2009). Words in context. Agreeing and disagreeing with allora. In G. Gobber et al. (Eds.), Word Meaning in Argumentative Dialogue, vol. 1 (= L’analisi linguistica e letteraria XVI, 2008/1, special issue), 205-218.

Miecznikowski, J. (2011). Construction types and argumentative functions of possibility modals: evidence from Italian. In F. H. van Eemeren, B. Garssen, D. Godden & G. Mitchell (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 1284-1297). Amsterdam: Rozenberg/SicSat.

Miecznikowski, J. (in press). L’argomentazione nelle recensioni on-line. In B. G. Fivela, E. Pistolesi & R. Pugliese (Eds.), Parole, gesti, interpretazioni. Studi linguistici per Carla Bazzanella. Roma: Aracne.

Miecznikowski, J. (under review). Envisager le futur dans les prévisions économiques. In L. Baranzini, J. Sánchez Méndez & L. de Saussure (Eds.), Le futur dans les langues romanes, Peter Lang.

Miecznikowski, J. & Musi, E. (under review). Text genres adapted to new contexts: the case of online reviews. In M. Casoni, S. Christopher, A. Kamber, J. Miecznikowski, E. Pandolfi & A. Rocci (Eds.), Proceedings of the Vals-Asla meeting “Language norms in context”, 12th-14th February 2014, Special Issue of Bulletin suisse de linguistique appliquée.

Musi, E. (2014).Verbi d’apparenza tra semantica e sintassi: il caso di sembrare in italiano antico. AION Linguistica 3.

Musi, E. (in press a). Evidential modals at the semantic-argumentative interface: appearance verbs as indicators of defeasible argumentation. In Informal Logic, 34 (3).

Musi, E. (in press b). Sembrare tra semantica e sintassi. Proposta di un’annotazione multilivello. In Proceedings of the XLVIII International SLI (Società linguistica italiana) Conference “Livelli di analisi e fenomeni d’interfaccia”, 26th-28th September 2013.

Pietrandrea, P. (2005). Epistemic Modality: Functional Properties and the Italian System. Amsterdam-Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Pike, K. L. (1954). Emic and Etic Standpoints for the Description of Behavior. In K. L. Pike (Ed.), Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of the Structure of Human Behavior (pp. 8-28). Glendale: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Rigotti, E. (2006). Relevance of Context-Bound Loci to Topical Potential in the Argumentation Stage. Argumentation, 20, 519-540.

Rigotti, E. (2007). Can classical topics be revived within the contemporary theory of argumentation? In F. H. van Eemeren, A.J. Blair, F. Snoeck Henkemans & C. Willards (Eds.), Proceedings of the Sixth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 1155-1164). Amsterdam: Rozenberg/SicSat.

Rigotti, E. (2009a). Whether and how Classical Topic can be Revived within Contemporary Argumentation Theory. In F. H. van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Pondering on Problems of Argumentation (pp. 157-178). Amsterdam: Springer.

Rigotti, E. (2009b). Locus a causa finali. Special Issue of L’analisi linguistica e letteraria, 559-576.

Rigotti, E., & Greco Morasso, S. (2010). Comparing the Argumentum Model of Topics to Other Contemporary Approaches to Argument Schemes: The Procedural and Material Compo¬nents. Argumentation, 24(4), 489-512. Riposati, B. (1947). Studi sui Topica di Cicerone. Milano: Vita e Pensiero.

Rocci, A. (2008). Modality and its conversational backgrounds in the reconstruction of argumentation. Argumentation, 22(2), 165-189.

Rocci, A. (2012). Modality and argumentative discourse relations: a study of the Italian necessity modal dovere. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(15), 2129–2149.

Rocci, A. (2013). Modal conversational backgrounds and evidential bases in predictions: the view from the Italian modals. In K. Jaszczolt & L. de Saussure (Eds.), Time: Language, Cognition and Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Squartini, M. (2004). Disentangling evidentiality and epistemic modality in Romance. Lingua, 114, 873-895.

Squartini, M. (Ed.). (2007). Evidentiality between lexicon and grammar. Special Issue of Italian Journal of Linguistics 19 (1).

Strik Lievers, F. 2012. Sembra, ma non è. Studio semantico-lessicale sui verbi con complemento predicativo. Firenze: Accademia della Crusca.

Stump, E. (2004). Boethiu’s ‘De Topiciis Differentiis’. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Usoniene, A. (2001). On direct/indirect Perception with Verbs of Seeing and Seeming in English and Lithuanian. Working Paper, 48, 163-182.

Whitt, R. J. (2011). (Inter)Subjectivity and Evidential Perception Verbs in English and German. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(1), 347-360.