When Congo Wants To Go To School – The Subject Matter

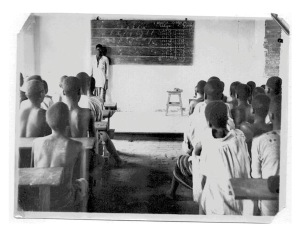

In the previous chapters, what was actually happening during lessons became dimly visible here and there. In this chapter this will be examined more closely. Learning in a class situation can be approached in many different ways. I assume in any case that a combination of various points of view is needed to achieve a picture of ‘reality’. What was taught? This can be deduced from the content of curricula tested by the commentary in inspection reports. It can also be partially deduced from the subject matter in the textbooks used. How was this taught? This is actually a question of the pedagogical principles the missionaries adhered to: did they talk about this? Did these principles even exist?

What was in the curriculum?

The curricula for subsidised missionary education have already been discussed in chapter two. By and large the period in question can be divided as follows, using the applicable curriculum guides: the period from 1929 to 1949, under the first curriculum (the Brochure Jaune), from 1949 to just after half-way through the 1950s, under the second (and third) curriculum and the second half of the 1950s, in which métropolisation was imposed (and, in principle, the Belgian syllabus should have been implemented). Apart from the fact that the transition between the different periods, especially between the second and third, is not very strictly defined, the first curriculum was noticeably enforced for the majority of the colonial period (taking the previously discussed proposal of 1938 into account). It did not seem worthwhile to analyse the changes in lesson content between the curricula of 1929 and 1948 in detail. After all it is almost certain that there is no general and direct concordance between what was required in the curriculum guides and what was actually taught. The curriculum guides only gave minimal norms, general guidelines and guiding principles. Obviously, it did not include the detailed contents of lessons. The third and final reason was that the curriculum was fragmented in the guide of 1948 through the introduction of the distinction between the normal and ‘selected’ second grade. This made an orderly comparison more difficult. The evolution of the two curricula in the area of subject content will only be touched upon very briefly.

However, it did seem worthwhile to make a summary comparison of colonial and Belgian curricula, especially to try to counter a certain representation. Otherwise it might be assumed too easily that the education in Belgian Congo was no more than a kind of occupational therapy. The researcher and the reader are faced here with a very subtle balancing exercise. On the one hand, the intention is to discover the reality, or at least to try: the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of school reality in the past. On the other hand, it is necessary to articulate what almost everyone will be thinking automatically when reading a story of the period: namely that ‘it wasn’t the way it is now’ and that the attitudes of a number of protagonists, namely the missionaries, were fairly ‘old-fashioned’, even ‘primitive’ or ‘backward’.

Of course such an opinion seems suspiciously similar to remarks made by the missionaries themselves about the Congolese (which partly causes them) but this does not mean they should not be mentioned. Nor should they necessarily be attacked with moral judgements but, on the other hand, they should be interpreted. In the first instance it is of course only human to distance oneself in one way or another from events that happened in other places at other times. We must, of course, avoid falling into an a-historical position but the reaction itself is not an historical aberration, in the sense of ‘very wrong at the time’. After all, in the same way the ideas of the missionaries are not to be considered as thoughts that ‘should not really have been thought’ and should have given rise to moral indignation. The foundations of the stance assumed in the colonial context are, after all, to be found in structures, positions and reactions in the home context of the colonisers. This can also be shown clearly in the context of the curricula.

The foundation for the colonial school curriculum must, after all, have come from somewhere. Intuitively, but also considering what was said before, it must be clear that no curriculum was designed ex nihilo and it was certainly not based on African precedents. The seeds were brought from Belgium. A first, even diagonal reading of the Brochure Jaune of 1929 makes this very clear. Considering that the preparation for that curriculum had already started in the first half of the 1920s, it is interesting to make the comparison with the Belgian curriculum guide for primary schools dating from 1922. With this we can also refer to the societal context in which the Belgian curriculum of 1922 was situated. As Depaepe et alii have already remarked, moral and civil education were perceived by the authors of this curriculum guide as the core tasks of a primary school. The quote referred to in this context is particularly relevant and recognisable from the colonial educational situation: “Primary school finds in itself its raison d’être; it is not created with the studies the pupils will do after that or the professions they could take up in mind; its aim is the same for all children entrusted to it: to prepare them as completely as possible for their destinies as man and citizen.”[i]

The colonial translation of this was even more straightforward and stripped of the enlightened ideals that were included in the Belgian version. The remark cited above, made in the curriculum guide for the second grade, made this clear: “Despite the selection which had been used during admission, not all pupils will go to special schools; thus they need to receive a training which is autodidactic and which educates men that are useful for their native environments.” Or, as it would later be worded, in the curriculum of 1948, as one of the three essential goals of primary education: “Provide an education which prepares all natives to live according to their proper genius, either in the ancestral environment or outside this environment.“[ii]

1.1. The Brochure Jaune and the 1922 curriculum guide

Primary school in the Congo comprised of five school years (2+3). A number of subjects were taught from the first to the fifth year. In the first place these were the basic subjects of religious education, reading, native language, arithmetic and geometric systems. Furthermore, hygiene, singing, drawing and gymnastics were taught in every year. For girls’ school, five years of sewing was added to this. French was optional in the first year. And finally there were three rather specific descriptions in the Brochure: the intuition lessons, general causeries/conversations and manual work. Geography was only taught in the second year. The course on theoretical agriculture only started in the third year. Finally, the curriculum of the second grade also prescribed handwriting or calligraphy and in the last year of the second grade girls received a course on childcare.

The explanation of the content of these courses varied in length and detail. The Brochure Jaune contained only the briefest information on religious education as this was left entirely to the religious authorities. But other subjects were also dealt with very summarily, like handicrafts for example. Often a kind of minimum curriculum was stipulated with this for the first year, which was systematically referred to for the following years, with the remark that the curriculum needed further elaboration. Whether or not this caused, in theory at any rate, the basic curriculum to differ fundamentally from that of the Belgian primary school is the question. For example, the Belgian curriculum guide of 1922 also referred to the religious authorities for the concrete elaboration of religion and morality lessons. Language education, on the other hand, was described much more extensively and with more detail and surrounded with conditions. Rather than making a long and elaborate comparison of the two complete curricula, it is perhaps more worthwhile to highlight a few parts: first a main subject, mathematics and then a ‘subsidiary subject’, geography.

1.1.1. Main subjects

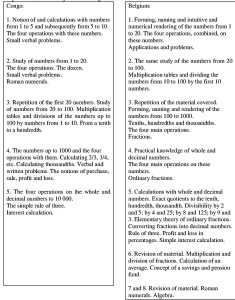

There are quite a number of parallels between the Belgian and the Congolese mathematics curricula of 1922 and 1929, respectively. In the Belgian curriculum, the pupils started by learning numbers from one to twenty. In the Belgian Congo, they only did this in the second year but the way in which the material was developed subsequently was similar. Similar systems were also used for teaching units of measurement. The basic principle here, as with mathematics, was apparently that the Congolese needed the first year to get used to the subject matter and would subsequently be able to assimilate more material at the same pace, year after year. Of course this meant that in the Congo education was stopped at the level reached in the fourth year in Belgium. As an illustration, a brief comparison is included of the subject matter as found in the Brochure Jaune and in the Belgian curriculum guide of 1922. It is clear that the Congolese mathematics curriculum was less extensive than the Western one, understanding that the limitation was largely due to a shorter period of primary education in general.

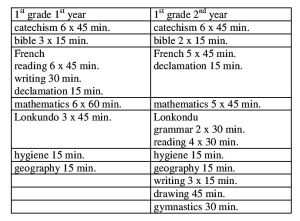

Comparison of the mathematics curriculum in the Brochure Jaune and the 1922 Belgian curriculum guide.

Is mathematics a measure for the other subjects? It seems logical to assert that mathematics has a somewhat more objective basis for comparison than other subjects. With this I mean that as far as mathematics is concerned there was not likely to be any pupil’s foreknowledge that differed from what was to be taught (which was the case for a language course, for example), though it must be noted that education experts in the 1950s had objections to this. For example, it was remarked in 1955 in the Revue Pédagogique Congolaise that young Congolese found it harder than the Belgians to grasp geometric forms.[iii] They grew up in a very different environment, after all, and in their early years they had only been confronted with flowing lines, while the straight lines of geometric figures were totally alien to them. This is in contrast to the Belgian child that grew up in an environment full of straight-lined figures and abstract concepts.[iv] “So, the European child is introduced at all times to the mathematical and geometric universe of the West. He hears people talking about numbers, hours, minutes, right and left. About countless objects with various shapes which have a set place in him.” According to the authors, the result of these things (including other areas and subjects) was a discontinuity between the natural first experiences and the subject matter taught at school.

The solution, however, lay in the systematic implementation of the Western education system through the further development of nursery education. On the opposite side we have the testimonial of Vertenten, who was already writing about the mathematical ability of his students in 1928: “If they come to the higher course they need to be good at mathematics and writing and for mathematics they need to know the four main operations well with whole numbers. That is the basis. From that I have, in a fairly short time, been able to teach them the following:

Can the same mechanisms be found in the other subjects? The other main subject, native language, is harder to study in a comparative perspective. The Congolese curriculum guide itself stipulated explicitly that the education should not be too literary, especially not in rural schools (the first grade of the curriculum). One result of this was that the curriculum stayed on the sober side on this point. After a somewhat more extensive explanation for the first year, in the division lecture the text was largely limited to the designation “lecture courante“, from the fourth year “lecture expressive“. Handwriting was only taught in the second grade, as mentioned above. A comparison with the Belgian curriculum guide is impossible here because the native language took a very central role and was the most extensively covered of all subjects. It was divided in various subdivisions like grammar, composition, pronunciation, etc.

1.1.2. Other subjects

However, the cited mechanisms did apply to other (subsidiary) subjects. Geography was only taught in the second grade according to the Brochure Jaune, whereas in Belgium it was provided for in the curriculum guide from the first year onwards. In the first grade however, it only consisted of an initiation into geographic observation. This comprised very simple lessons about the most important geographical information, taught very concretely and without definitions. The curriculum guide further stipulated that this material would, in the first year, be part of the exercises in rhetoric during the native language lessons (about which no further details can be found in the paragraphs concerned). Of course, in the Congolese curriculum nothing was mentioned about this because geography was not taught in the first grade.

Cover and first three pages of Etsify’okili: geography textbook from 1957, compiled by the MSC Frans Maes. This textbook was written for use at the mission school in Flandria. Honoré Vinck, Lovenjoel.

In the causeries, for example, in the second year the accidents géographiques de la region had to be discussed as well as natural phenomena like night and day, wind, rain, thunder and lightning. In practice it also happened that geographical concepts were discussed in the reading lessons.[vi] The subject matter for the second year was more parallel in the curriculum. As in the Congo, the emphasis in Belgium was also placed on simple concepts, starting from the pupil’s concrete living environment. One would leave the classroom and go and explore the world outside in increasingly larger ‘circles’: the school, the village, the town, the region, etc. As appears from the example reproduced here (figure 1), this was also put into practice by the MSC. The world opened up for the boys through their own classroom, the school building, the football field and… the church.

The worldview that the young Congolese retained from their geography lessons finally did remain more limited than that of their Belgian counterparts. While in Belgium the borders were crossed to neighbouring countries in the second year, for the Congolese the world outside the Congo was limited to Belgium.[vii] Of course this was not to be considered a foreign country. Some parallels between both curricula can be taken fairly literally. In the fourth year in the Congo, for example “A few big trips on the sphere” were studied. This was also to be found literally in the Belgian curriculum guide for the second year. However, there it was specified which voyages of discovery were meant exactly, something for which there was no place in the Congolese curriculum. ‘Belgium’ was covered but only in the second year. The history of the occupation of Congo was on the curriculum in the fourth year. Further geographical concepts concerning the ‘motherland’ were only covered in the last year but it was a very selective approach: “Situation, some cities, rivers, railways (length), some information about the richness and the activities of the Belgian population, the Belgian royal family.“[viii] In other subjects the issue of ‘Belgium’ was not covered a priori.

1.1.3. Causeries

The Congolese curriculum further contained the subject causeries. These were lessons during which the teacher had to tell educational or edifying stories. It was more or less an extension of what was called “Moral and citizen formation” in Belgium. However, the formulation of the content of the causeries in the 1929 brochure is revealing in itself and contains in itself a colonial curriculum. In the five years of primary school the following were to be covered in succession:

Attitude in the classroom, in church, in the street, in the village, relationship with fellow students, school rules, people, things and scenes from their own environment; first notions of politeness.

- Politeness: respect towards civil and ecclesiastical authority; aiding elders or the weak; tenderness towards animals; geographic layout of the region and natural phenomena.

- Role of Europeans in the country; habits and practices of the country; politeness.

- Habits and practices of the country: superstition, bad influence of magicians; natural phenomena: lightning, hail, earthquakes, eclipses, the dangers of alcohol consumption, the use of hemp and other narcotic plants.

- The most important stipulations from the decree on the chefferies;[ix] obligations of the population concerning censuses, taxes, militia; most important legal stipulations concerning firearms, hunting, alcohol, hemp and gambling.

In comparison: the Belgian curriculum guide of 1922 summed up in a number of points the various ‘obligations’ that the students had to be taught. In the first and second years this mainly related to individual and generally altruistic virtues, such as cleanliness, caution, order, regularity, moderation, dignity (individual) and respect, goodness, servitude, friendliness (altruistic). In the third and fourth years so-called “national” education was taught, as well as professional obligations: “The work considered in the company; the solidarity of workers. Requires conscientious work. The employment contract: obligations of employers and workers. Mutual support in the professions.” The principles and values touched upon in both curricula were thus not very different, often they even corresponded remarkably well. Yet there was a difference: in the case of the Congolese it seems as though fewer words have been wasted, the tone is slightly firmer and the content was more geared to the acceptance of authority. Finally, the inclusion of a number of issues like “superstition” and “hemp use” were certainly dictated by local circumstances.

1.2. The position of girls

Finally the explanation about moral and civil formation in the Belgian brochure of 1922 also contained a number of extra paragraphs with considerations about girls and women, under the heading “Observations“. The moral education in girls’ schools should be aimed at aspects of home and family life. This concerned the role of young women in their family and the relationship with other family members (parents-in-law); how to become a good housewife; the qualities of the young woman in the household: politeness, foresight, charm, simplicity, equanimity, goodness and devotion. And the most important fault to be avoided: nosiness! Further, marriage had to be considered, its preparation and, of course, the manner in which a woman should function in a marriage. Finally, children also had to be considered, as well as everything involved therewith.

There was not really a specific section devoted to girls’ education in the Brochure Jaune. Girls’ schools would only be treated separately from the first year onwards in the 1938 curriculum. The brochure did however devote some attention to the domestic science school and in that context female concerns or subject matter were of course specifically covered. In the 1929 curriculum, the domestic science school was still a rural economics school, which in itself is revealing as to the social position of woman in the eyes of the colonisers. This education would last three years. The only classes of general education during the time were French (optional) and Arithmetic and Metric systems, in which subject matter from primary school was mainly repeated and how to keep small household accounts was taught. The course Hygiene also consisted of material already covered, with additional classes in childcare. Besides this, agriculture, housekeeping and conversation were provided as subjects. The last two received considerably more attention than the other subjects in the brochure. Of course, a wide variety of practical activities and abilities were covered in housekeeping. In the Causeries the following topics were to be treated: “The role of the woman in the family; to insist on financial matters and the foresight she will have to show; thoroughly combating the blacks’ tendency to excessive eating and drinking when abundantly available, of having big parties in order to display their resources; to combat the customs, the harmful practice of religion, customs and practices to which, in general, women are more attached than men; to be responsible for caring for and educating children.”[x] To this it was only added that these lessons should be played out as much as possible in the field, on the farm, in the kitchen and in the workshop. The teaching method suggested in the curriculum was that the pupils would afterwards return to the classroom and, under guidance from the teacher, write down what they had just learned.

One conclusion is evident: women were clearly treated differently, both in Belgium and in the colony. In both cases they had to fulfil a specific role and needed preparing for it. In both cases they had to fulfil extensive domestic tasks. Apparently, their roles had to be described far better and more precisely than those of men. Typically this was worded with far less circumlocution in the colonial context. In Belgium, an extensive description was used to express that other things were expected from women, although there was no underlying image of equality. In the Brochure Jaune, on the other hand, it was asserted without too much ado that women were more ‘susceptible’ to certain deficiencies or faults. More generally it can be posited – whether concerning boys’ or girls’ schools – that from the outset the curriculum of the colonial primary school corresponded to the image of a small lapdog being dragged on a lead by its owner: it follows in the same direction but can never keep up, let alone catch up with its owner.

1.3. The 1948 curriculum

The reform implemented in the 1948 curriculum has already been discussed in the first chapter. One consequence of the increasing contribution of the administration in the organisation of the education was, among others, that organisation and subject content were discussed in separate brochures from then on. Despite this, subject content was left relatively undisturbed, even though twenty years had passed since the implementation of the previous curriculum. This was certainly the case for the first grade and the ordinary second grade. There were not really any new subjects. The curriculum guide did now include an “observation exercises ” section but this simply seems to have been a new name for what was previously called “intuition lessons”. The French lessons were described in more detail but it was emphasised that it should be “very simple teaching”.

In the ‘selected’ second grade, the subject content was further elaborated and other priorities were imposed. French lessons were given a prominent place, immediately after religion and the native language. Fairly detailed guidelines were given, more than for any other subject, while it remained a subject as any other in the normal second grade. The theoretical agriculture lessons underwent the opposite fate: they were completely central in the normal second grade and were abandoned in the selected second grade. A section on “manual work” was kept but formulated very concisely. The same trend extended into the second and third year. A “professional” subject, with a practical impact, existed for the normal second grade. The biggest difference, of course, was in the fact that the selected second grade was a year longer than the normal one. In the last year, as was the custom, a great deal was repeated but a large portion of new material was also added.

The curriculum in practice

How much of the curriculum was actually implemented in the classroom? There are two ways of finding out more about the content of the lessons. Both ways give a kind of ‘side-view’ and must for that reason be used in a complementary way. On the one hand there are the inspection reports, which have already been dealt with extensively. On the other hand there are the colonial schoolbooks. The colonial schoolbooks offer insight into the selection made by the teachers. The schoolbook, like the curricula, does not of course represent reality. They both mainly say how things should be. Even so, we can employ these types of sources here because the books are also the product of a specific context. Thus they can present parts of the atmosphere and intellectual reality. To that I wish to attach the educational convictions of the missionaries, inasmuch as they existed and were expressed.

2.1. Inspections

In the earliest inspection reports only scarce information is to be found on the subject matter. Of course, this is linked to the absence of binding rules concerning subject matter, curriculum and inspection. The earliest official documents I found date from 1927. In addition, there cannot have been any inspections much earlier because the missionaries were only there from 1925. The first curriculum proposal also dates from then. But reports from before the implementation of the curriculum of 1929 do exist. In a report from 1927 about the girls’ school in Coquilhatville, it was pointed out that the school was only in its first year. The girls had never previously received any school education. The Sister herself remarked rather optimistically: “Over the 1 year the school has been open, we have already noted real progress.” What exactly was happening at this time was not so important but it is certain that sewing was done and the garden was worked in. Besides this no real intellectual activity can be detected. It was reported that the children had not yet been able to sit exams and further that “In order to obtain discipline we first applied exercises of order and discipline, while marching to rhythmic songs.”[xi] The Daughters of Charity insisted on discipline. They considered that the morality of their girls had deteriorated under the influence of their environment and they attached by far the greatest importance to discipline and zest for work. The following school year they also reported, after listing all the problems, that: “Meanwhile, despite the problems, we noted great progress amongst the children as far as discipline is concerned as well as work.“[xii] Oddly enough the report does refer to an official curriculum that was supposedly being followed. Jardon, the travelling inspector, also frequently referred to an official curriculum.

In the reports about the mission activity in this period, it is clear that the education was not yet bound to a structured curriculum. On Sunday afternoon, the Sisters ‘welcomed’ all the children: “We welcomed all the children, both the young and older ones, that came to us. We used our time for different exercises: prayers, songs, games.” A few years later this already produced some results because the report of 1930 informs us that a choir had developed from the Sunday meetings and that learning new songs was much easier, since most of the children could now read. As well as the actual school activity, which was only discussed very briefly, a ”tailoring school” was also referred to. This meant that four out of five days, the pupils were occupied with sewing for two hours. They covered needlework, crocheting, knitting and making clothes. The clothes they made themselves were given back to them at the prize draw. The children at the nursery school made plaits with raffia.[xiii]

In the report about the schools at the various mission posts which Vertenten provided for the state inspector in 1929, he only deals with a number of subjects briefly. Mostly he mentioned handiwork, sewing, mathematics and religion. Nothing was said about the content of these subjects; indeed, there was not enough space on the pre-printed forms for this.[xiv] In a report about the second grade of the boys’ school in Bamanya, from 1929 or 1930, he referred to the Brochure Jaune for the first time. The lessons had been ‘inspired’ by the curriculum brochure. It appears that here the official instructions were not experienced as particularly obligatory either. It is not too clear what guidelines were used exactly. Probably they were from the organisational project of 1925, even though this was not an official, legally binding text. The project fitted into the framework of agreements made between the mission congregations and the government from 1925-1926. Via this detour, the text was probably seen to be a legal guideline anyway.

Hulstaert also referred to a curriculum in September 1928. He said that the primary school in Flandria had organised three school years. In the first year, reading and writing were taught. In the two following years mainly mathematics was taught, at various levels. The implementation of the provided curriculum had not worked yet. This would only be possible step by step, according to Hulstaert. The provincial inspector, Jardon, also referred to “the curriculum” in two reports from June 1929. In Bokuma, this curriculum was followed meticulously for all subjects. In the report on Wafanya, Jardon gave slightly more information: “For religious education, reading, writing and the local language, the students have the right level. As far as arithmetic is concerned I notice a rather considerable progress but the fundamental notions are insufficiently known.“[xv] Moreover, the missionaries did not have enough control over the moniteurs and the main result of this was that the subsidiary subjects were neglected. Presumably, the curriculum of the Brochure Jaune was already being referred to here. The definitive text supposedly dates from 1928, though it was only published in 1929. However, the indications in the reports are not really decisive on this point.

In his inspection report of 1930 about the Sisters’ school in Coquilhatville, Vertenten concluded that it was not surprising that the pupils stayed below the level of the curriculum. The school, as is clear from the report, was only in the first stage (the first year) and had to struggle with the low level of the staff and the poor language ability of the Sisters, as well as the material problems mentioned earlier. Vertenten only referred explicitly to language, mathematics and religion and made a very brief reference to geography in the fourth year. The children were learning to read and write French, though this was not the intention. The mathematics lessons also took place in French. The Sisters who taught in the second grade had no command of the local language but even the moniteurs who taught in the first grade – under the supervision of the Sisters – taught mathematics in French. The situation was probably of such a nature that the inspector, who praised the Sisters extensively, was already happy that there was a school that functioned on a regular basis at all.[xvi] In the rural schools, in any case, there was also no mention of complete teaching activities. In the report to the education inspection in 1932 this was worded rather more optimistically: “One should not lose sight of the fact that in numerous villages Christian education existed where thousands of children received religious education and learned to read, write and do mathematics at the same time.“[xvii]

In a report about the girls’ school in Bamanya, Sister Auxilia gave a detailed overview of what exactly the curriculum represented at the school. At that time there were 96 girls. A moniteur taught the three first years, the two higher years were taught by a Sister. Sister Auxilia (who was headmistress of the school) gave a whole list of subjects in her report. For each, she indicated what material was taught in which year. It shows clearly where the emphasis lay:

Religious education was taught every day in every class, the Sister wrote: “1st 2nd 3rd year, the minor catechism, 4th and 5th, the major catechism.” A division was made depending on the nature of the lessons: Father Jans explained, the moniteur taught “teaching and explanation” and Sister Auxilia herself taught baptism preparation classes and provided Holy Communion after morning mass. She referred to the catechism pictures as her teaching tool: “ Next year a new series of pictures (for each child separately) will be used. Catechism in pictures with the catechism of HG Cardinal Gasparri.” And finally: “In the 3rd, 4th and 5th years, children practice writing questions without mistakes.” There was also a separate subject “Biblical history”. Here pictures were also used but it was taught completely by moniteurs: “A great emphasis is placed on the lively but unaffected transmission of lessons. 4th and 5th also take notes on the classes, aided by questions.”

Writing took place according to the method of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. In order of class the following was on the curriculum: “1st: letters with small connections of consonants and vowels (pencil), 2nd: all letters and small words (calligraphy in ink), 3rd: capitals, 4th and 5th: capitals and exercises for fluent and regular writing.” Apparently there had been dissatisfaction with the results of these lessons in the past (from Hulstaert) and so the Sister pointed to the fact that special attention had been paid to this, with good results.

For reading, Hulstaert’s reading method was used. The Sister spoke of “the first and second book”, which refers to the Buku ea njekola I and II, the reading books published by Hulstaert in 1933. It is striking that every year was started with the first book. The higher the class, the further one got. In the fifth year the pupils worked through the first book and a part of the second, “as well as other literature“. Later, Alma Hosten also described a similar system.[xviii] However, also in the lower classes “the 1st and 2nd books by the English were used alternately. From the 3rd year onwards attention is paid to reading tone and the natural rendering of the subject matter in their own indigenous manner.” So English books from Protestant congregations were also used, which Vinck later confirmed.[xix]

The sister was quite brief concerning mathematics: “1st and 2nd year: according to the curriculum. 3rd idem except for the decimal system. 4th and 5th: all calculations up to and including 1000. 5th went over 1000 but no particular value was attached to this.” (…) “A great emphasis is placed on sums of the metric system, particularly calculations with francs, of which especially also the way of writing was studied.”

In language education a distinction was made between various parts. It certainly related to Lomongo.

– grammar lessons: “typed courses by P. Hulstaert.” (…) “The higher classes are behind because we have only had the books 1.5 years – and because the material was so unfamiliar both to us and the moniteurs.”

– dictation: “for all classes in proportion to their knowledge.”

– style: “writing out by heart a song learned, with points of departure for discussing objects, customs, situations, etc.”

– “style and conversation lessons or general development classes converge here. Here the children are given the opportunity to explain their own songs, dances or games and so when it comes to learning plays, the children can express their opinion freely and frankly instead of slavishly accepting what we tell them when they don’t agree with us in their hearts.”

About gymnastics: “The same principles are used for gymnastics and dancing. The European way had to yield to the typically indigenous way. The rhythmic movements connected to Congolese conceptions and understandings are the material for beautiful expressive movements. The blacks find their own dances beautiful, really beautiful, but performed as one coherent whole and in order. In this way, with her own singing, her beloved ngomo, gymnastics keeps its appeal for the children and they still receive all the movements of head, hands, feet and torso. Next year we hope to stimulate the children to take part in games, such as rounders, handball, korfball – also for passing the time on Sunday afternoons.”

Then a few shorter statements follow. French was barely mentioned: “for the three highest classes, spoken French – very little or nothing is written.” About singing only this was noted: “melodies by Ghesquiere and Hullebroeck are taught.” Drawing was also only briefly mentioned: “The children made sketches, without the use of a ruler or compass.” The geography lessons were taught in the two highest classes and were limited to very general concepts: “General concepts, continents, oceans. The provinces of Congo and their capitals – further the physical division; the Congo river and its side rivers, the lakes, etc. From Tsjyapa, division with prominent places.”

The last item was sewing and this was also treated most elaborately. It was taught in all classes, two afternoons from three to five. Seen relatively, this was rather a lot but the attention devoted to it by the Sister in the report does seem out of proportion. While a total of three pages were devoted to all the other subjects, this subject took up about one whole page, in which a detailed description was given for every year and every object the pupils had sewed, crocheted and knitted.

So sewing was the dominant element on the curriculum. Oddly enough, not a word was said about agriculture in this report. From an inspection report of 1938, five years later, it appears that the same school devoted seven and a half hours a week to “practical agriculture lessons”, namely every day from seven until eight in the morning and one afternoon from three thirty until five in the afternoon. Other practical activities became more important depending on how the girls progressed with their studies. Sewing lessons were taught for two hours in the first year but in the last (fifth) year, it already occupied four and a half hours. “Homework” (housekeeping) went from half an hour to an hour and a half.

According to a document from 1939, the causeries in the first and second year had to cover the following issues: “Hunting and, in connection with this, the most notable animals and their way of life. Fishing and, in connection with this, the seasons. Swimming, the healthy but also the damaging things for the body. Dancing, the good and bad dances, pointing to the dangers of the latter, the stimulation of folk dances and games. The dead, mourning, the dance, the burial. Drinking, moderate drinking, drunkenness as a scandal, damages the health. Smoking and chewing tobacco, unfitting for girls, damaging to the health, bad for the teeth. Encouraging love for the monarchy through photos, stories, the flags of Belgium, Congo and the Papal flag, the benefit of becoming acquainted with the state in its various workings and institutions. Politeness in general, why we should be polite, politeness in church and at religious ceremonies, courtesy in oneself through order and neatness of dress, taking heed of one’s expressions wherever one goes, in all one’s doings, while eating, towards parents and elders, etc.”

Father Cobbaut, who inspected the school in 1946, only made a short report and only mentioned in it that, in all classes, all subjects were regularly taught and that they were all generally well known. So there is not too much information to be gained from this. At the domestic science school (which was on a higher level than the primary school) the curriculum was, at that moment, neatly divided into two: in the morning the pupils in groups of two or three carried out all possible sorts of housework in turn. The afternoon was reserved for theoretical instruction. Based on the timetable used in all schools, this of course meant that only a minimal amount of time was devoted to the theoretical education.[xx]

Sister Auxilia again in 1947: “The morning periods are devoted to housework like mending sheets, tights, socks, sewing and patching children’s, women’s and boys’ clothes, washing, ironing, starching, folding, native and European cuisine, domestic chores, further sewing, tooling tree bark, raffia. This year a new kind of embroidery with raffia was undertaken, namely filet in raffia, very beautiful, if the children become skilled at it. In the theory classes, apart from the revision of the ordinary school subjects and religious studies, the main subjects taught are: hygiene, agriculture and cattle breeding, home economics, childcare, etiquette classes and other development classes, French lessons and drawing paper patterns. 1 x a week the girls worked in their gardens with great diligence.” Further, every morning the land was worked (probably outside the framework of the lessons). The government inspection thought this was far too little. The inspector actually only had remarks concerned with the time spent on agricultural activity. At the primary school this was better than elsewhere, given that there at least the ordinary portion of morning labour was on the curriculum. Meanwhile, the pupils of the last year of the second grade worked in the kitchen, “and as a result they did not devote themselves to any rural work.” The domestic science school was a complete disaster: “Meanwhile at the rural economics school, the timetable is not well balanced and does not leave enough time for agricultural work“[xxi] Also in a report Hulstaert wrote in 1944, the smallest part of theoretical subjects appeared in the timetable of the domestic science school. According to him only two afternoons a week were filled with other than practical subjects. In this short time religion, mathematics, reading, writing and theoretical revision of the practical work were taught.[xxii]

Hulstaert also inspected the boys’ school in Bamanya in 1944. In the light of what will be said later about the conflicts between Hulstaert and the Brothers of the Christian Schools, who ran this school, it is not surprising that he added the necessary measure of criticism to this. The official curriculum was followed and not that of the Brochure Jaune. The extent of the difference in how the timetable was filled is clear from the reproduced summary given by Hulstaert in his report for the first grade. The timetable for the second grade was presented less clearly and could not be reconstructed completely. From the timetable of the first grade it is clear that the emphasis was on French, not on Lonkundo, which troubled Hulstaert a great deal, of course. The other subjects (hygiene, geography) were taught for a great part in French and so he wrote in the report: “The courses are almost entirely devoted to French and mathematics.” The Causeries also served primarily for practicing French.

There were a few other deviations from the normal curriculum, which Hulstaert had used systematically as his norm, even though the Brothers had in this case chosen to use a different curriculum. “It is noticeable here that from the first year the curriculum (with respect to mathematics, JB) of the state schools is used, not that of the Catholic schools (however that has not even been changed in the new plan of 1938 in the sense of the official programme). Whatever the reason may be for accepting the state curriculum, I believe that the curriculum is made to be followed and must not be changed on one’s own authority.” For example, no intuition classes were taught here, even though according to Hulstaert this was “one of the most important educational subjects on the curriculum“. This school also made time available for agricultural activity, but not very much: only an hour and a half or an hour and forty-five minutes a week. Sometimes midday “studies” were devoted to gathering small pieces of firewood or leaves. The pupils needed these to prepare their food. All in all this came down to a “considerable deviation from the subject and hour divisions proposed by the government brochures“.[xxiii]

The fact that the guidelines given in the curricula or by the government were not strictly applied is very clearly proved by information in an inspection report written by Gaston Moentjens from the school year 1952, about the primary school and teachers’ training college in Bamanya. The extensive report (twelve pages of text) was supplemented with a number of tables in which, for all years, the norm given by the government was compared to the timetables implemented by the missionaries (in Bamanya these were the Brothers). The impression given by these tables is not really surprising. In the first grade, religion was systematically taught more than recommended (4.5 to 5 hours instead of 3). Native language was divided into three subthemes: reading-writing, copying-dictation and recitations. Far less time than recommended was spent on the first two and far more on the third, just as the component elocution. Less time was also spent on mathematics than was actually requested, as was gymnastics. However, drawing, singing and certainly agriculture and traditional activities were taught far more extensively. So much the more remarkable because, in contrast to the prescribed number of hours, five and a half hours more were taught. This difference was almost entirely caused by religion, agriculture and sewing lessons. Especially in the first grade there were sometimes notable differences. In the normal and selected second grade, the prescribed timetable was followed much more closely. Only singing (much more) and mathematics (much less) retained times that were clearly deviating.[xxiv]

Both the missionary inspector Moentjens and the state inspector Eloye were at that time fairly critical towards the differences between the prescribed and applied time allotment. Moentjens pointed an accusing finger at the moniteurs: “The curricula imposed by the school regulations are, in general, quite well implemented. Moniteurs are well informed to follow the curriculum guide they are given but I don’t think that the moniteurs are able to resist their tendency to teach things outside the guide. In any event a more effective control is imposed.”[xxv] In his conclusions, though, he did move the responsibility more to the missionaries themselves: “Regarding didactic organisation I cannot recommend the headmaster enough to exercise his position as headmaster fully by organising practical and theoretical methods at schools better. This includes drafting good timetables, well defined distribution of subject matter from the different program guides and of all the prescriptions from the educational organisation.”

2.2. The subject matter in the schoolbooks

Of course the schoolbooks offer a second possibility to become acquainted in more detail with the subject matter the pupils could receive at school. Honoré Vinck has already done a comprehensive study of a number of the schoolbooks that were published and used by the MSC.[xxvi] In a series of studies he discussed aspects of form and content of primarily MSC reading books. From this it appears all the more that Hulstaert was very active and very influential in this area. Even so, this picture must be looked at with caution. Hulstaert had, as was often the case, his specialisation and his hobbyhorses.

In the first years after their arrival (in 1926) the MSC had to appeal to existing publications due to the absence of their own publications. Thus, they also asked the Brothers of the Christian Schools to bring as many of their own books as possible.[xxvii] A number of publications from the Trappists were also used. Sister Auxilia again, in 1933: “For arithmetic method the mathematics books of the Brothers of the Christian Schools are followed. These fulfil all the requirements of the curriculum. 1st and 2nd year worked through everything, in the 3rd year we allowed the 10-part fractions, while 4th and 5th year did all the basic operations. For reading method we used the books by the English until August, in September all classes adopted the reading method (3 parts) of Fr. Hulstaert, as well as the 4 parts of his grammar. 4th and 5th studied 1st part in the past months, 2nd and 3rd have also started but have not yet finished the first book.” Use was made of anything to hand, it could even be Protestant. The writing method of the Brothers of the Christian Schools was also applied, the Sister added in her report.

In due course, however, more and more of their books were written in the regional language. Vinck stated: “The range of books in Lomongo for linguistic and religious education is quasi complete. The whole curriculum of primary school and even secondary school has been covered in the local language, Lomongo. This library has been established within a few years, mainly by one man only and according to his rather pedagogic, linguistic and ideological choice in particular.” In the publications by Hulstaert himself and also later in the studies made about him, attention was paid primarily to books on language and reading lessons. For other subjects, for a long time different books were often used, whether or not they were translated into Lomongo: “The scientific books (often in a provisional state) would come some ten years later. It was a conscious and chosen strategy. Hulstaert has underlined it a lot in contemporary articles.“[xxviii] Vinck, however, did not indicate in which texts this was.

In any case, it also appears from his study that for a great number of years existing books were used for some subjects. It appears however from the first part of this chapter that the weight of a number of subjects was often less important in the curriculum. Also for mathematics, for example, material from the Brothers of the Christian Schools or the Marist Brothers was used for a long time. A number of these books were translated into Lomongo but others were written in Lingala or in French and were also used like that. For geography, publications were only provided in the 1950s, primarily by Frans Maes. Further, a whole series of fairly practically oriented schoolbooks was published in the framework of so-called observation lessons.[xxix] These ‘books’ (often only a bundle of copied pages) contained a number of texts on the most diverse subjects: descriptions of traditional objects and their use, interactive skills (politeness), hygiene, animals. There was an amalgam of subjects, which were sometimes also taken from the schoolbooks made for other courses. Furthermore, specific books existed for the fields of hygiene, botany and zoology, interactive skills and drawing.

2.2.1. History: Ngoi and the whites

From the early 1940s, Hulstaert himself worked on a history textbook, “un cours d’histoire mongo“. It was based on a number of reading lessons from one of the reading books he had written in the 1930s, Buku Ea Mbaanda. The history textbook itself, Bosako wa Mongo (History of the Mongo), only appeared in 1957 but several of the texts used in it had previously been published in the periodicals of the MSC, which also appeared in the regional language. They had probably already been used in this way. The logical consequence for the history lessons must have been that only the teacher disposed of textual material.[xxx] A fairly unique text written by Paul Ngoi was included in the publication of this history book. Ngoi was a pupil of the MSC who was rather close to Boelaert and Hulstaert and was involved as an assistant in editing a number of MSC publications in Lomongo, Le Coq Chante and Etsiko.[xxxi] In 1939 Ngoi, who can probably be considered an évolué avant la lettre, wrote the text Iso la bendele (“Us and the Whites”). The text was intended to be an entry for a literary competition, organised by the periodical Africa, published in London.

Ngoi’s text is a surprising account of traditional customs. The concept certainly does not fit in the Western tradition of historiography, as it was used in the schoolbooks. It is not a chronological summary of political events, forms of state and cultural characteristics of particular periods. Instead, Ngoi treated a number of social problems (sloth, lying, theft) and mechanisms (marriage, death, family, jurisprudence, authority) of the traditional Nkundo society. The difference, for example, from history books as used in secondary education by the Brothers of the Christian Schools is considerable. The texts appear very much to be accounts of contemporary events, but they weren’t. They testify to a way of narration, probably typical of cultures that relate their history through the spoken word, which is very close to the way people from those areas still tell stories of their (or ‘the’) past.[xxxii]

Indeed, Ngoi points out at the beginning of his article that there is a great lack of respect for the local population on the part of the whites: “Because, even at present, most of the Whites believe that our ancestors were wild beasts, without any morals and only with mistakes, without any virtue.”[xxxiii] The article was almost completely taken up in the schoolbook, which was compiled by Frans Maes. Ngoi’s descriptions seem objective though. There are no real judgements or criticisms, at least not at first sight. A number of statements are surprising on first reading, such as in the chapter on laziness, which starts with the following phrase: “Here the laziness is innate and gets confirmed with growth.” Which, however, does not mean that later in the text the author actually claimed that the Mongo were naturally lazy people. On the contrary, after a series of examples, he concluded the chapter with: “This is the least we can say about laziness here. It is different from the concept the Whites have.” The chapter “Lust“, about experiences of sexuality “aux temps des ancêtres“, was also objective-descriptive. The antropophagie (“people-eating”) was also treated here in a short paragraph.

As mentioned above, the chapter in question contained a complaint about the bad conditions caused by the arrival of the whites. Armed combat, rubber exploitation, the damage to villages, destruction of local authority, destruction of the family structure, spread of disease and depopulation of the area were examined successively. Further, there were paragraphs on the suppression and loss of local culture and language and on the temptations caused by wealth, luxury and sexual excesses. Each and every charge was levelled against the influence of Western society. In the midst of all this misery, faith was the only ray of hope: “We don’t complain in the same way as we do about the other importations of the Whites.” On the contrary, gratitude was appropriate here: “We greatly thank the Whites for that.”[xxxiv]

A number of considerations have to be made here. Vinck continually questioned the extent of the originality of this text and whether there was any far-reaching influence from the missionaries when it was written. The fact that Paul Ngoi was, for a very long time, an assistant of Hulstaert, supposedly played a role in this. From the perspective of this chapter, however, the exact answer to this question is irrelevant. After all, the text was used in a schoolbook by the MSC. The missionaries must thus, in any case, have been in agreement with the statements made therein. The schoolbook seems, at first glance, to be an example of how the subject matter, in this case history, became more Africanised, or was at least moved away from a European perspective. A few marginal notes need to be added here. Firstly, the use of this text is situated fairly late in the colonial period and thus its possible influence coincided with decolonisation. Secondly, Vinck remarked that there are a number of internal contradictions in the text. The matters covered in the first descriptive part of the text (and thus of the book) were not necessarily positively qualified. Vinck also posited that Ngoi himself often criticised the practices he described. But in the last chapter, where the intervention of the whites was covered, the tone changed dramatically.

This text was an example of the often ambiguous stance of the MSC towards the local culture. This, in its turn, was a result of the position they took regarding a number of social issues, both at home and in the colonial context. Its meaning for the content of the lessons and thus for the pupils is in itself just as ambiguous. The tone of the last chapter was very radical and very negative. The question is how this one example should be evaluated in the totality of the subject matter. Firstly, we can assume that the tone of most schoolbooks and subject matter contrasted somewhat with this critical stance. In other history lessons (often parts of schoolbooks for other subjects, such as geography or religion), a very different tone was employed. An example of this is Bosako w’oyengwa (Histoire Sainte) from 1935, in which the arrival of the whites is also described. The text of the lesson in question, reproduced here, takes a far more ‘traditional’ stance. Secondly, the impact of this book can be questioned, given that it was only used in the sixth and seventh year.

The Whites in the Congo

The kings of Europe had learned the news of the Congo. They found out it was a big country with a big population. But its people are cruel and sin is very distinct in them. They go to war between themselves, they put each other in prison and they shoot lots of people. The Arabs came to the Congo from the East at Tanganika and through the rivers Tsingitini and Lualaba. They defeated the natives; they captured lots of slaves and took them to their own region to sell them there.

The kings of Europe were greatly upset by this news. They gave the Belgian King Léopold II authorisation to keep Congo in order to slow down the wars, to chase away the Arabs in order to free the men from slavery and to teach them the intelligence of the Whites and to raise their wealth through trade.

Léopold had sent his men to Congo. But the natives did not appreciate the arrival of the Whites and their teaching; they defeated them and plundered their possessions. Then, the Whites campaigned against the natives. They spread throughout all regions of the Congo and they defeated the natives and dominated them. There were a lot of battles amongst the Arabs and certain men, because they were very cruel. But the Whites had weakened their strength. When the wars ended, they freed the slaves and started to embellish the country. [xxxv]

Extract 3 – Reading lesson on the arrival of the whites in the Congo, from Bosako w’oyengwa III.

2.2.2. The reading books written by Hulstaert

The reading book, as a specific form of schoolbook, is an interesting object of study in this matter, for several reasons: of all the material, it probably had the greatest distribution; it was used from the first year; the MSC and also Hulstaert in particular, attach quite some importance to it, relatively speaking; this type of book contains a great number of reading lessons, which cover a wide variety of subjects. In this way, they present a good overview of the themes covered during the lessons and of the most important messages the missionaries imparted or wanted to impart to the Congolese youth. In a few recent studies, analyses of reading books published by the MSC were already discussed.[xxxvi] The conclusions of these studies concern didactic, educational and broader ideological aspects of the reading books and their use in the classroom. These aspects are treated separately here, but it is clear that they are correlated.

Technically

The method Hulstaert used to teach the children to learn to read was specifically concerned with writing and forming words and sentences and learning letters. Whether this was all thoroughly thought-out is another matter. Vinck calls Hulstaert’s spelling method “anti-langue-africaine” but immediately adds that he probably deviated from international standards in this regard because it was too difficult to apply them for learning the language at school.[xxxvii] Further, he did take the characteristics of Lomongo into account, such as grouping certain consonants and vowels and the fact that this language contained seven different vowels. Hulstaert, of course, had written out the majority of Lomongo himself and could thus also determine arrangement and style himself. We can assume that he was very gifted and well grounded in this area and worked with a great deal of insight.

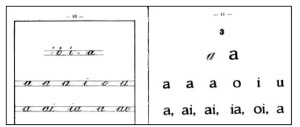

This does not mean that his method of working was didactically well thought-out, let alone innovative. The didactic guidelines he gave in the reading books Buku ea Mbaanda are about the clearest statements he made in this area. Hulstaert wanted to teach the phonetic sounds and subsequently teach the pupils to write the accompanying written letters. In this way, various letters were learned and subsequently placed together, first in meaningless wholes, later in meaningful words. Van Caeyseele calls this an example of a bottom-up method. Keeping more with the spirit of the time, I would sooner call it an analytic method. This by way of analogy with the analytic-synthetic method as was generally used in the first decades of the 20th century. This method assumed that the letters had to be learned by separating them in a series of ‘known’ words. The ‘new’ pedagogy would distance itself more and more from this method to elaborate the ‘synthetic’ elements within it (more visual, more global, working with meaningful sentences and texts instead of just words, which were not necessarily related).[xxxviii] Hulstaert situated himself even further on the other side. It was typical of his method to treat the letters one by one when learning them. The letters themselves had to be ‘deconstructed’. He even wanted to show how letters were actually composed of other letters. A ‘u’, for example, was an addition of two ‘i’s. It was also presented in the instructions to the moniteur in this way.[xxxix] In part II of the same book there were further instructions for teaching capitals.[xl]

Educational-didactical

The Hulstaert method was a system he had designed quite intuitively, without taking account of (other) educational principles. There is no reference here to a global reading method using the context in which words and letters are found, although this method was known at the time. Vinck and Van Caeyseele refer to Alma Hosten, alias Sister Magda[xli] on this point. Vinck said: “It seems to me that she had an influence on Hulstaert but it was impossible for me to perceive the exact outline of it.“[xlii] Van Caeyseele goes even further in her study: “She was informed of the insights into the new school movement and from these criticised Hulstaert’s gradually surpassed method.“[xliii] It is probably exaggerated to speak of real ‘criticism’ in this context. Indeed, Hulstaert himself published a contribution by Hosten in Aequatoria, in which she mentioned reading books.

In this she clearly referred to Hulstaert’s method: “Every reading method for beginners should be illustrated. Illustration captivates! The separation of words into syllables is an unhappy business. It is unmethodical, literally distracts instead of concentrates. I have taken the following test: let a particular group read syllable by syllable, connect those syllables into words and finally achieve fluent reading. Have another group take no account of the divisions between syllables. Group 1 had significantly more trouble than Group 2. It will probably be said: the pupils should not read in separate syllables or parts! But: why place these sections in front of the students and weaken the strength of the reading image then? That is to disturb the literary understanding; when there could be a beautiful harmony between image and speech.” (…) “Small lessons are far more interesting than separate sentences without a connected content. Those lessons also prepare a suitable base for the style practice. They can also be a great help for a global reading method.”[xliv]

From the correspondence between Hulstaert and Hosten it seems that they got on well with each other and that there was some agreement on Hosten’s educational approach. In a letter from April 1942 Hulstaert wrote to Hosten: “You know that I agree with you completely concerning the purpose and principle methods of teaching.”[xlv] For her part, Hosten complained to Hulstaert about a colleague in Boende, Sister Martha, who she did not feel was cooperating in the implementation of modern teaching methods. For those who read between the lines some envy between the Sisters cannot be discounted.[xlvi] At any rate, Sister Magda boasted that she had qualifications and professionalism as opposed to her colleague.

Instructions for the teacher

The method for teaching reading and writing.

- Repeat the previous lesson but don’t take too much time over it.

- Then the new sounds. Pronounce a few words in which these sounds are used. Show the pupils some objects which are meaningful through these words (by fact or by drawing).

- The pronunciation of the sound. A few pupils pronounce the sound individually and then all together.

- Homework. The pupils think about words which start with the new sound. Then they try to find words in which the sound is located in the middle or at the end of the word. They pronounce it without haste in order to learn how to control the sound in a very clear way. If they don’t understand something, or if they hesitate, help them by asking questions.

- Writing. Write the letter neatly on the blackboard. Explain the pupils the different parts of the letter. Then teach them the block capitals.

- Reading exercise. The pupils read the written letters first and then the letters in block capitals.

- Writing exercise. They write the letters on the drawing board with care. After that they correct the mistakes. Then some people write the letters on the blackboard. After that you make them remove what they have written.

- Put the new letters up onto the blackboard next to the old ones; (parts of words, the words themselves, then phrases). One by one they read them out loud and then all together.

- They read the lesson in the book.

- They write the words that are on the blackboard, after that the words that are in the book.

The method for writing a capital letter:

- Teach the shape of the letter in italics at the blackboard.

- Write your letter in different parts and unite the parts in order to create an entire letter.

- Show the pupils the comparison between this letter and some previous letters, or they look themselves.[xlvii]

- Some pupils try to write the letter at the blackboard and their friends should look for mistakes and differences between the letter written by the pupil and the one by the teacher.

- The pupils copy the letter either onto the drawing board or into their notebooks. After that they correct it.

- They imitate the language which is used in the book.

- Don’t fail to check the force with which the pupils try and the way they hold their pens and the way the notebooks spread out in order to get all things straight.

Extract 4 – Instructions to the teachers, from the MSC reading book Buku ea njekola eandola la ekotelo

Ideologically

Although it is said that Hulstaert pays less attention to the religious in his reading lessons than is traditional, that influence was present nevertheless.[xlviii] From recent research it appeared that this did not follow from the chosen themes so much as from the way in which they were addressed.[xlix] From the analysis of the contents of a few reading lessons, in MSC reading books and those of other congregations, it is apparent that an explicitly religious motif (as the theme of the reading lesson) was not always as clearly present. Where Kita stated in the case of the Pères Blancs that 28% of the reading lessons (from reading books published in the 1910s) analysed by him had an explicitly religious theme, Vinck and myself came to only 12% in the case of the MSC’s Mbuku ea Mbaanda (first published in 1933) studied by us. In a comparable reading book from the 1950s by the Dominicans (working in Uele, North-East Congo) that portion was even lower. Without drawing general conclusions from a rough comparison of three different congregations, I think that the period of publication can explain this difference to some extent.This should be nuanced by stating firstly that the religious theme was part of a broader moralising motif and these were both completely intertwined. When the facts are seen in this light then Pierre Kita’s remarks in his study of the reading books of the Pères Blancs must be agreed with: “Religion very clearly occupies a predominant place: not only the themes that are completely dedicated to it, representing around 28% of the total, but also the biggest parts of the texts which are related to social life and even to studies are influenced by religious morals.”[l] In the study of the MSC and Dominican books the same characteristic came up: “Regarding this topic you should take note that the two types of handbooks contain many references to God and to his glorification, in all kinds of lesson.”[li] Secondly, most reading books, whatever the date of publication, had a long life and were often used for several decades. Kita expresses this in the case of the books by the White Fathers. This was the same for the MSC, as is apparent from correspondence. This is especially informative as to the moralising element remaining imposingly present in the schoolbooks until the end of the colonial period.Educational ideas: a measure of nothing?

3.1. Influences and allies

In the second year of Aequatoria (1939) an article appeared signed with the initials Z.M., standing for ‘Zuster Magda’ [Sister Magda].[lii] This article was unique, for two reasons. As far as known she was the only woman ever to publish a contribution in the original Aequatoria series. Apart from this the content was also unusual for the periodical: Hosten wrote a report on the manner in which she had worked with the school curriculum. The subtitle of the article was literally: “Application of the primary school curriculum”. She treated each subject that was taught in turn and referred to the curriculum brochure. The general conclusion that can be drawn from the article is that the sister certainly did not feel herself bound to the curriculum to the letter. This started with the first subject, native language: “The education in letters received an ample share, due to its undeniably great educational worth.” Yet the curriculum made different emphasises. In the causeries she said quite determined: “The useful and formative subjects of the curriculum were covered, the remaining were omitted.” In the lessons on medicine: ”Apart from the curriculum, special attention was given to illnesses of local importance.” From the article it was apparent that much attention was given to the development of the language and mathematics lessons. The descriptions of the performances in the lesson ‘native language’ were very extensive. The sister mentioned the kinds of exercises that were done and which topics the students had mastered. In the case of mathematics it seems special attention was given to fractions. She also described the methods used.

May the Sacred Heart of Jesus be loved everywhere

Boende, 16.7.42

Very reverend Father Superior,

I thank you most warmly for your last letter. I often thought that I had become uninterested in class matters. The judgement of others (…) But when I read your letter, I felt clearly that I was not at all indifferent to your approval or disapproval. And I saw clearly – never before so well – how you are a light and support to me. It is most human I know but I confess it to you most simply.

Dearest Father Superior, allow me to speak my heart. As far as Sister Martha is concerned… I think it has been enough. I have nothing against her personally and I do not believe that she has anything against me personally. [It is a] very different case than that of Sister Beatrijs. But she is not the person to be left in education any longer. You remember the fate of earlier moniteurs … and now hers have had enough. They are good and simple boys… they are exemplary, they are our teachers and have a simple good and loving spirit… it is all I ask.

Not long ago 3 of Sister Martha’s moniteurs went to Father Henri and said plainly that they could not take it any more with Sister Martha, that they had had enough of it. 1000 proofs, facts, … Far too many to list. Father Henri told them to continue in their duty, not to criticise anyone and to wait.

You can see, good Father Superior, all things allowed, that intervention is needed. Her adjustments to new methods are extremely weak… a continuous stumbling block for me, a brake that slows the system. Lately during a visit to the class with Father Paul I saw that she had dropped the mathematics method, without having asked my good advice or permission, and was ploughing on in her own way. The reading method? As long as it is examined in that way… I cannot bring about anything definite… I could continue to write for a long time in this way.

Finally it is the spirit of Boende that she will never be willing or able to accept, for she has never loved the blacks in her heart. She says it is singing that wrenches here and everything would be solved if she could teach singing again… Talk. Her spirit has never been different… The singing has made the mood less sweet and finally unbearable… And if she would only see that she is not the person to teach singing, just because she is not an educator.

If only she was just harmful to the teachers like this… I could easily tolerate this for another 20 years… but she is damaging to education and that is as precious to me as the apple of my eye. It is a great pity for education that such people busy themselves with it, even if they finally achieve something. Education must work inwards… and such people have never looked into the child’s soul. I do not judge people in any way by saying this… for I have my faults as she does.

Dearest Father Superior, it is starting to be hard for me… besides, I do not believe she feels much for education… success – eventhough it is imagined success, the downsides were far greater than the success – kept her up and so still tolerable in some way. I do realise, very reverend Father Superior that it is hard now to find a solution.

Extract 5 – Letter from Sister Magda to Gustaaf Hulstaert. Aequatoria Archive.

Hosten was a professionally trained secondary school teacher and this clearly showed from the language she used. She referred several times to “the occasional method” or the “purpose occasional education”. She was apparently very interested in these methods and tried to encourage the moniteurs to join her in this. That was not a simple assignment she said: “This is still a plague to those who naturally adhere to the ‘système des tiroirs’ and who don’t dare or know how to make bridges between the parts of a subject or between the separate subjects.” From the report it also appears that repetition was a very important element. In the subject ‘mathematics’ each year started from the beginning and then went further according to the ‘excentric method’: “In which the learning material is treated 1) every year and 2) always more extensively.” She further clarified that she was not using this excentric method exclusively but intermittently with the concentric method. This meant that the subject matter was always studied in more depth. She did mention that the system was not fully completed yet: “Yet to teach a subject in this way demands a purposeful division of the subject matter. But we have not been able to do this yet for most subjects, due to lack of time. Because this takes a lot of personal preparation.”

The meaning of this text should not be underestimated. In the inspection reports that can be found on the schools in this period, educational concepts and ideas were almost never being referred to. The emphasis was far more heavily on facts and material data. Especially the fact that Hulstaert put this section in his periodical has its importance. After all, he published the article because he felt that it described a situation as it should be. Aequatoria was not a mission periodical; the propaganda element certainly did not play a part. The article had a more normative function. In other words, it can be supposed that in most other schools things were far less progressive and modern. From the last statement it can be deduced that the lessons given by the moniteurs were in many cases not so structured.[liii] This puts the direct importance of this specific text for the image that the contemporary reader forms of the colonial class into perspective. Sister Magda was not representative. More than that, she was an exception. Likely she was even an exception in her own environment, which is also apparent from the letter she wrote to Hulstaert about her colleague, Sister Martha. At that moment she was also a young, ‘fresh’ power. Someone who, for the sake of an educational ideal, worked actively, cared heart and soul for her work, and with a desire to put her accumulated knowledge into practice.

Hulstaert had an interest in the ideas tested by Hosten and certainly was not opposed to them. His correspondence with her was in a fairly friendly tone; he did not criticise her article. From other articles it is only too clear that he would speak his opinion about other’s articles without hesitation if he found it necessary. A good example of this was the publication of the article “Pédagogie Civilisée et Education Primitive“. The article was written by Vernon Brelsford, a British district commissioner in Nigeria. It was originally published in English in Oversea Education. Hulstaert summarised it and translated it into French and published it in 1945 in Aequatoria. He added: “No doubt that this remarkable study will interest our readers. We took the liberty, counting on the well-known British open-mindedness, to add a few considerations as notes.”[liv] In his article the British functionary strongly emphasised the differences between the two types of education. The comparison between the two was consistently to the advantage of Western education. Hulstaert did not hesitate to add some strong doubts on this opinion in the footnotes of the article. In this he presented himself as critical both of the opinions that the author expressed and of European society. He also put into perspective all the differences that Brelsford had emphasised. In opposition to the Brit he saw no incompatibility between the education systems in Africa and Europe and no supremacy of the European system. He did not see parallels between the new trends in education and African education. That conclusion would show too much interpretation. He did enumerate some characteristics of the African system that were essential to him and stood up for the Africans.[lv]