When Congo Wants To Go To School – Appendices & Bibliography

1 – Quantitative data relating to education in the Belgian Congo, 1930- 1940

2 – Quantitative development of education in the Belgian Congo between 1938- 1958

3 – Quantitative development of education in the Belgian Congo between 1930-1948

4 – Figures relating to the state of education immediately after independence, in Congo and in Coquilhatville

5 – Development of educational spending in the colony and the proportion of educational spending in the total budget 1912-1940

6 – Diagrams of the organisation of education according to the “Dispositions Générales” 1948

7 – Some quantitative data relating to the missionary presence in the Belgian Congo

8 – Primary school program – Extract from the Brochure Jaune

9 – Letters from Pierre Kolokoto to Paul Jans, from the Aequatoria Archive

10 – Letters from Hilaire Vermeiren to Paul Jans, from the Aequatoria Archive

11 – Contextual analysis of “La Voix du Congolais”

12 – The history of the emergence of schools in the Equator province, by Stephane Boale

13 – “Extrait de la causerie du Ministre des Colonies, M. Jules Renquin avec les premiers missionnaires catholiques du Congo-Belge” “Extract from a talk given by the Minister for the Colonies, Mr Jules Renquin, to the first Belgian Catholic missionaries to the Belgian Congo”

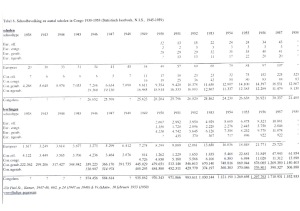

Appendix 1 – Quantitative data concerning education in the Belgian Congo, 1930-1940

The situation in 1930

A report drawn up on request of the Permanent Committee of the Colonial Congress and which appeared in the records of the third National Colonial Congress offers a number of indications concerning the quantitative development of education at that time. However, the figures stated were not given any further clarification. A distinction was already made at that point between state education, independent subsidised education and independent non-subsidised education. 11 “groupes scolaires” were referred to in the document. These were probably the official (state) schools. They accounted for 12 760 pupils. According to this document, 131 250 pupils were in independent subsidised education, divided among 2 377 schools. Apparently, no figures were available for independent non-subsidised schools: it was stated that they were “légion” and that the number grew each year.

However a far more detailed report on education from the same period does exist, namely the report drawn up by Edouard De Jonghe for the meeting of the Institut Colonial International in Paris in 1931. According to the author the figures cited were representative for the situation on 31 December 1929. De Jonghe did not give any general figures for the whole colony but gave very detailed data per region and per school. Based on the figures in this report, there would have been 131 534 pupils in primary Catholic subsidised education.[i] De Jonghe also gave figures for non-subsidised education, more specifically for the Protestant schools, which around a total of 160 000 pupils supposedly attended. These figures were to be taken with a pinch of salt according to De Jonghe because “ces chiffres n’ont pas été contrôlés” and as far as the rural schools were concerned, the figure was of all the pupils enrolled at the schools, not only those who attended school regularly. Thus subtly insinuating that as opposed to this, the figures for the Catholic schools were actually “clean” (i.e. regarding only the pupils that really attended school) .[ii] As far as the Catholic non-subsidised schools were concerned, De Jonghe could only give an example: in the Kwango district there were 52 schools, with 8 057 pupils, which were subsidised in 1929. On the other hand, there were 2 658 non-subsidised schools, with 44 980 pupils.[iii] It seems out of the question that this figure should only be accounted to the Protestant missions. It probably also relates to the fact that many Catholic schools were not yet ‘subsidy ripe’ at this stage.

The situation in 1934

For this year there are data brought together in the Annuaires des missions catholiques by Corman. There are no general data on the quantitative development of education in the 1924 edition. However, there are in the second edition, from 1935. The division of the subsidised schools into rural and central schools was used when creating the overview statistics. That gave 284 central schools with 50 333 pupils and 9 652 rural schools with 289 456 pupils for the Belgian Congo alone (without Ruanda-Urundi). This means the total number of pupils in primary education had to be estimated at around 350 000 (the 13 “official” schools were mentioned separately). Again, the data do not seem very “clean”: there are hiatuses in the statistics and no data were published for some regions. Moreover, the publishers of the Annuaire seemed aware that it was difficult to obtain correct quantitative data. As the total result of his own data, Corman gives 10 291 primary schools with 477 004 pupils (for both the Belgian Congo and Rwanda-Urundi). Elsewhere the same publication also gives figures from the Apostolic Delegation: 8 152 primary schools with 440 778 pupils. Both series of figures were supposed to reflect the situation on 30 June 1934 but altough Corman’s results were higher, it was admitted that the data from the Apostolic Delegation were more reliable.[iv]

The situation in 1936

Depaepe and Van Rompaey give an overview table per vicariate and educational level, also based on data published by the Apostolic Delegation in the Congo from 1936. They mention 11 145 schools with 444 082 pupils. If these figures are corrected (and the figures for Rwanda-Urundi filtered out) this gives slightly over 10 000 schools with approximately 380 000 pupils.

The situation in 1938

The figures of the N.I.S. for 1938 are limited to the number of schools and number of pupils in general for two different types of education: the official schools and the independent schools. 7 official schools for the Congolese are mentioned.[v] Together they accounted for slightly more than 4 000 pupils. Consequently, this probably relates to a number of school groups. In addition, this statistic gives 4 268 subsidised schools, which together numbered 222 369 pupils. No distinction is made on the basis of the level of education.[vi]

In his article from 1940, Oswald Liesenborghs gave a whole series of figures on colonial education which reflect the development of the number of schools and pupils from 1929 to 1938.[vii] He did not mention any sources for this data. These figures are shown in the table below:

| 1929 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | |

| official education | |||||||||

| schools | 11 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 7 |

| pupils | 3618 | 5182 | 5380 | 5649 | 5567 | 5691 | 5337 | 4589 | 4122 |

| subsidised education | |||||||||

| schools | |||||||||

| 1e gr. | 2532 | 2773 | 3579 | 3780 | 4326 | 4217 | 3740 | 3720 | 3635 |

| 2e gr. | 163 | 201 | 241 | 273 | 284 | 394 | 473 | 492 | 577 |

| pupils | |||||||||

| 1e gr. | 119563 | 144150 | 164313 | 180522 | 167339 | 184902 | 168573 | 168493 | 177004 |

| 2e gr. | 8162 | 12229 | 16090 | 19862 | 21832 | 27013 | 31615 | 35478 | 42426 |

These figures may be supplemented with the data cited by the Dominican Steenberghen in his master’s thesis. He stated that, according to the Apostolic Delegation in Congo, in 1939 there were about 13 000 non-subsidised Catholic schools with approximately half a million pupils and 9 000 Protestant schools with approximately 300 000 pupils.[viii]

The situation in 1940

Julien Van Hove, who was an official at the Ministry for Colonies for many years, gave a fairly extensive and detailed overview of the whole colony in an article from 1953, L’oeuvre d’éducation au Congo Belge et au Ruanda-Urundi.[ix] The following table summarises the most important figures from it. This only relates to the figures for primary education and only for the Belgian Congo. The statistics were gathered over a longer period but can be used here as a supplement to the previous data for the thirties. The number of schools followed by the number of pupils is shown each time:

| 1.1.1930 | 1.1.1940 | 1.1.1945[x] | 1.1.1948[xi] | |

| official schools | 92 968 | 73 624 | 63 624 | 53 464 |

| subsidised 1e grade | 2 532119 563 | 4 446195 401 | 5 020243 918 | 6 966320 591 |

| subsidised 2e grade | 1638 162 | 65047 980 | 83965 840 | 98384 311 |

| total subsidised | 2 699127 725 | 5 096243 381 | 5 859309 758 | 7 949404 902 |

| independent schools | –– | 17 910463 950 | 19 193483 253 | 19 072513 049 |

| total primary education | –– | 23 013710 955 | 25 302798 265 | 27 078923 165 |

The division of these statistics seems to fit better with the previous data from Liesenborghs. The difference to the two figures given previously (from the Apostolic Delegation, for 1934 and 1936), in my opinion, lies in the fact that they relate to all Catholic education, both subsidised and non-subsidised. In the two following series (those of Liesenborghs and Van Hove), a distinction is made between these two types, and “independent schools” must be understood as both Protestant and non-subsidised Catholic education.

NOTES

[i] This figure corresponds surprisingly well with the figure given in the report from the Permanent Comittee and is therefore probably based on the same sources.

[ii] One difference between the figures cited here for the Catholic and Protestant schools should be mentioned: The figure for the Protestant schools is the total figure and includes all possible types of school whereas the figure for Catholic education only relates to primary schools or departments.

[iii] De Jonghe, E. (1931). L’enseignement des indigènes au Congo Belge. Rapport présenté à la XXIe session de l’I.C.I., à Paris, mai 1931. p. 39-93.

[iv] Corman, A. (1935). Annuaire des missions catholiques au Congo Belge. Bruxelles: Edition Universelle. p. 380 & 392-393.

[v] This must therefore be understood as: schools founded by the state and run by missionaries.

[vi] See data and source references in the overview table in appendix 2.

[vii] Liesenborghs, O. (1940). L’instruction publique des indigènes du Congo Belge. In Congo: Revue générale de la Colonie Belge. XXI. n°3. p. 267. In another article that was published at around the same time, Liesenborghs gives other indications with much less detail and also presented with the necessary reserve: “It should firstly be stated that the figures shown here differ somewhat, but only insignificantly, from indications in other publications. It is not always possible to find all the information required in the official annual reports and other sources.” [original quotation in Dutch] The figures relate to the situation in 1938. In his article he mentioned 1 official boys’ school with 3 368 pupils (!) and 1 girls’ school with 180 pupils. In independent education no distinction was made with regard to gender: in subsidised education he mentioned 4 212 schools with 219 430 pupils and in non-subsidised education 18 257 schools with 501 852 pupils. No sources were given for these figures. Liesenborghs, O. (1940). Het Belgisch koloniaal onderwijswezen. In Vlaamsch Opvoedkundig Tijdschrift. 1940. XXI, 7

[viii] Steenberghen, R. (1944). Les programmes de l’école primaire indigène rurale au Congo Belge. Leuven: unpublished Master’s thesis.

[ix] Van Hove, J. (1953). L’oeuvre d’éducation au Congo Belge et au Ruanda-Urundi. In Encyclopédie du Congo Belge. Bruxelles, dl. 3, p. 749-789. Van Hove was the successor to Edouard De Jonghe within the colonial administration.

[x] The total differs from the sum of the various categories because a number of “6 preparatory” years have to be added. In this year this relates to 44 schools and 1 630 pupils.

[xi] The same as for footnote 10: this relates to 52 schools and 1 750 pupils.

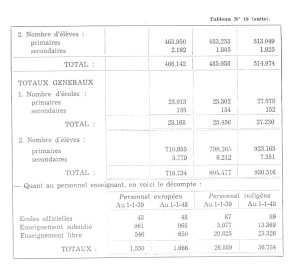

Appendix 2 – Quantitative development of education in the Belgian Congo between 1938-1958, figures from N.I.S. (Briffaerts, 1995)

Appendix 3 – Quantitative development of education in the Belgian Congo between 1930-1948, according to the brochure with the Plan Décennal (1949)

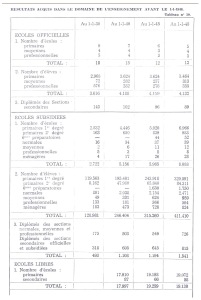

Appendix 4 – Figures relating to the state of education immediately after independence, in Congo and Coquilhatville (figures from BEC, 1963)

1. Congo – primary education (BEC 1963, p. 19)

| school year | network | ||||

| official | Catholic | Protestant | other | total | |

| first | 23161 | 534375 | 119150 | 1608 | 681294 |

| second | 19088 | 301511 | 69420 | 1275 | 391294 |

| third | 15114 | 216031 | 50661 | 659 | 282465 |

| fourth | 12075 | 162461 | 38948 | 327 | 213811 |

| fifth | 11319 | 123141 | 30915 | 223 | 165598 |

| sixth | 10568 | 78941 | 24362 | 399 | 114270 |

| total | 94325 | 1416460 | 333457 | 4491 | 1843733 |

2. Congo – secondary education (BEC 1963, p. 19)

| school year | network | ||||

| official | Catholic | Protestant | other | total | |

| first | 10090 | 16744 | 2379 | 1647 | 30860 |

| second | 7762 | 10151 | 1210 | 696 | 19819 |

| third | 2726 | 6124 | 535 | 315 | 9700 |

| fourth | 1520 | 3692 | 315 | 109 | 5636 |

| fifth | 511 | 961 | 46 | 77 | 1595 |

| sixth | 198 | 448 | 34 | 59 | 739 |

| total | 22807 | 38120 | 4519 | 2903 | 68349 |

3. Congo – number of schools (“estimations raisonnables”, BEC 1963, p. 21)

| boys | girls | mixed | total | |

| complete primary education | 668 | 336 | 353 | 1357 |

| incomplete primary education | 1468 | 135 | 5613 | 7212 |

| number of classes | 14106 | 5552 | 13895 | 33787 |

4. Total school population in Catholic primary education at the beginning of the school year 1962-63 in the Coquilhatville diocese (approximately corresponds to the vicariate of the MSC) (BEC 1963, p. 24)

| total | boys | girls | ||||

| year | diocese | province | diocese | province | diocese | province |

| préparatoire | 110 | 160 | ||||

| 1e | 5149 | 41879 | 3291 | 30306 | 1858 | 11573 |

| 2e | 2958 | 26174 | 1920 | 19601 | 1038 | 6573 |

| 3e | 2277 | 20932 | 1520 | 16242 | 757 | 4690 |

| 4e | 1793 | 16967 | 1229 | 13631 | 564 | 3336 |

| 5e | 1334 | 12497 | 948 | 10314 | 386 | 2183 |

| 6e | 898 | 7161 | 724 | 6247 | 174 | 914 |

| 7e | 24 | 166 | 24 | 143 | 24 | |

| total | 14432 | 125776 | 9656 | 96483 | 4777 | 29293 |

5. Congo – secondary and post-primary education (BEC 1963, p. 31)

Division of the schools by church province

| post-primary (pp) schools | secondary (sec)schools | schools with pp or sec sections | ||||

| province | boys | girls | boys | girls | boys | girls |

| Léopoldville | 32 | 34 | 33 | 37 | 3 | 11 |

| Coquilhatville | 6 | 13 | 27 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Stanleyville | 16 | 16 | 33 | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| Bukavu | 5 | 4 | 29 | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| Elisabethville | 7 | 10 | 26 | 13 | 1 | 6 |

| Luluabourg | 7 | 13 | 30 | 10 | 3 | 3 |

| total | 73 | 90 | 228 | 84 | 10 | 29 |

6. Secondary education in detail: comparison of Coquilhatville (province) and Congo

A. Number of classes from 1st October 1962 (BEC 1963, pp. 33-35, 40-42, 47-49)

| Coquilhatville | Congo | ||||||

| totaux | garcons | filles | totaux | garcons | filles | ||

| cycle d’orientation | 68 | 60 | 8 | 729 | 545 | 184 | |

| moyennes générales | 4 | 4 | – | 11 | 10 | 1 | |

| moy. hum. pédag. | 21 | 16 | 5 | 247 | 156 | 91 | |

| moyennes familiales | 1 | . | 1 | 7 | . | 7 | |

| moyennes ménagères | – | . | – | 4 | . | 4 | |

| human. latin-grec | 15 | 15 | – | 178 | 160 | 18 | |

| human. latin-math | 5 | 5 | . | 18 | 18 | . | |

| humanités modernes | 3 | 3 | – | 110 | 81 | 29 | |

| scientifiques A | 3 | 3 | – | 46 | 46 | – | |

| scientifiques B | – | – | – | 19 | 16 | 3 | |

| Economiques | 2 | 2 | – | 34 | 28 | 6 | |

| prof. tech. agricoles | 5 | 5 | . | 27 | 27 | . | |

| autres techniques | 1 | 1 | – | 62 | 47 | 15 | |

| autres prof. | 10 | 9 | 1 | 113 | 103 | 10 | |

| artistiques | – | – | . | 14 | 14 | . | |

| médicales | – | – | – | 15 | 4 | 11 | |

| totaux secondaire | 138 | 123 | 15 | 1634 | 1255 | 379 | |

| apprentissage pédag. | 5 | 3 | 2 | 22 | 14 | 8 | |

| artisanal, apprentissage | 12 | 12 | 191 | 189 | 2 | ||

| ménagères post-prim | 8 | . | 8 | 64 | . | 64 | |

| ménagères pédagog | 25 | . | 25 | 216 | . | 216 | |

| médicales | – | – | – | 2 | – | 2 | |

| totaux post-primaires | 50 | 15 | 35 | 495 | 203 | 292 | |

| totaux généraux | 188 | 138 | 50 | 2129 | 1458 | 671 | |

B. Number of pupils per 1 October 1962 (BEC 1963, p. 55-57, 62-64, 69-71)

| Coquilhatville | Congo | ||||||

| totaux | garcons | filles | totaux | garcons | filles | ||

| cycle d’orientation | 2111 | 1892 | 219 | 26686 | 21115 | 5571 | |

| moyennes générales | 55 | 55 | – | 71 | 68 | 3 | |

| moy. hum. pédag. | 399 | 327 | 72 | 5858 | 4038 | 1850 | |

| moyennes familiales | 8 | . | 8 | 112 | . | 112 | |

| moyennes ménagères | – | . | – | 47 | . | 47 | |

| human. latin-grec | 203 | 203 | – | 3054 | 2821 | 233 | |

| human. latin-math | 49 | 49 | . | 110 | 110 | . | |

| humanités modernes | 81 | 81 | – | 3263 | 2878 | 385 | |

| scientifiques A | 33 | 33 | – | 772 | 771 | 1 | |

| scientifiques B | – | – | – | 348 | 329 | 19 | |

| Economiques | 21 | 21 | – | 444 | 382 | 62 | |

| prof. tech. agricoles | 69 | 69 | 380 | 380 | . | ||

| autres techniques | 23 | 23 | – | 1204 | 1074 | 130 | |

| autres prof. | 87 | 87 | – | 2271 | 1894 | 377 | |

| artistiques | – | – | . | 99 | 99 | . | |

| médicales | – | – | – | 127 | – | 127 | |

| totaux secondaire | 3139 | 2840 | 299 | 44846 | 35959 | 8887 | |

| apprentissage pédag. | 146 | 112 | 34 | 660 | 488 | 172 | |

| artisanal apprentissage | 251 | 231 | 20 | 3926 | 3830 | 96 | |

| ménagères post-prim | 132 | . | 132 | 1566 | . | 1566 | |

| ménagères pédagog | 598 | . | 598 | 5112 | . | 5112 | |

| médicales | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| totaux post-primaires | 1127 | 343 | 784 | 11264 | 4318 | 6946 | |

| totaux généraux | 4226 | 3183 | 1083 | 56110 | 40277 | 15833 | |

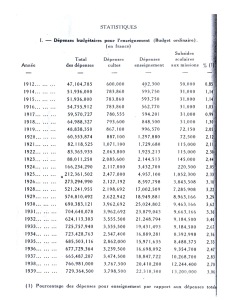

Appendix 5 – Development of educational spending in the colony and the proportion of educational spending in the total budget 1912-1940 (Liesenborghs, 1940)

Appendix 6 – Diagrams of the organisation of education according to the “Dispositions Générales” 1948 (Plan Décennal, 1949)

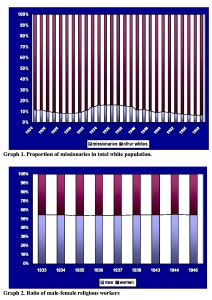

Appendix 7 – Some quantitative data relating to the missionary presence in the Belgian Congo (source: Statistical Yearbook N.I.S.)

The following table shows the ratios from graph 2 with a more detailed division according to the origin of the missionaries (this only relates to the so-called “white” population):

| 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1943 | 1944 | 1946 | |

| Belg. male | 1130 | 1181 | 1255 | 1338 | 1477 | 1584 | 1675 | 1694 | 1828 |

| Belg. female | 933 | 981 | 1071 | 1137 | 1253 | 1318 | 1389 | 1381 | 1530 |

| Belg. total | 2063 | 2162 | 2326 | 2475 | 2730 | 2902 | 3064 | 3075 | 3358 |

| Foreign male | 334 | 322 | 309 | 312 | 356 | 346 | 331 | 301 | 319 |

| Foreign female | 426 | 419 | 409 | 413 | 458 | 484 | 478 | 451 | 473 |

| Foreign total | 760 | 741 | 718 | 725 | 814 | 830 | 809 | 752 | 792 |

| Total | 2823 | 2903 | 3044 | 3200 | 3544 | 3732 | 3873 | 3827 | 4150 |

Table 1 – Religious workers in the Congo – ratios according to gender and nationality, 1933-1946

The “Katoliek Jaarboek” from 1961 gives the following figures with regard to the composition of the group of religious workers for 1959, although this is for the Belgian Congo and Rwanda-Urundi together. The various categories are given the same names as they were in the publication. “Foreign” is used for predominantly white, non-Belgian religious workers, as in the previous table.

| Belgian missionaries | 2 070 |

| Belgian brothers | 696 |

| Belgian sisters | 2 450 |

| Total Belgian religious workers | 5 216 |

| Diocesan priests | 586 |

| Local brothers | 514 |

| Local sisters | 1 184 |

| Total Congolese religious workers | 2 284 |

| Foreign missionaries | 576 |

| Secular priests from other countries | 61 |

| Foreign brothers | 225 |

| Foreign sisters | 755 |

| Total foreign religious workers | 1 617 |

Table 2 – Religious workers in the Congo – ratios according to gender and nationality, 1961

Appendix 8 – Primary school program – Extract from the Brochure Jaune

Programmes et Méthode [i]

ECOLE PRIMAIRE DU PREMIER DEGRE

PREMIERE ANNEE D’ETUDES.

Religion: programme à déterminer par les autorités religieuses.

Lecture: étude des lettres et de leurs combinaisons. En première année d’études, la lecture, l’écriture et l’orthographe doivent s’enseigner en même temps. L’étude d’une lettre comprendra donc: la recherche et l’étude du son, sa représentation, l’écriture de la lettre par les élèves, la combinaison de la lettre avec d’autres lettres étudiées précédemment, des exercices de lecture, d’écriture et der, dictées; comme il faut empêcher que les élèves ne prennent l’habitude de lire sans se rendre compte de ce qu’ils lisent, tous les mots nouveaux seront soigneusement expliqués et le maître vérifiera fréquemment si les élèves comprennent bien le texte lu.

Calcul: notion concrète des cinq premiers nombres, additions et soustractions concrètes sur ces nombres; étude des cinq premiers chiffres, additions et soustractions; étude simultanée des nombres et des chiffres de 5 à 10, additions et soustractions sur les 10 premiers nombres, ensuite multiplications et divisions sur les mêmes nombres; petits problèmes oraux. En 1re et en 2e année d’études, il est désirable d’adopter pour la division la forme de “la 1/2 de…”, “le 1/3 de…”, “le 1/4 de…”, “le 1/5 de…”.

Système métrique: notion intuitive du mètre, du litre, du franc, du kilogramme, du demi-litre, du double-litre, du poids d’un demi-kilogramme, de deux kilogrammes; nombreux exercices de mesurages-longueurs, liquides, matières sèches de pesage, de paiement; petits problèmes oraux.

Leçons d’intuition: parties du corps, vêtements, classe, objets de la classe, fleurs, fruits, plantes, animaux. Pour les leçons d’intuition l’on suivra généralement la marche suivante: analyse libre de l’objet, analyse dirigée, comparaison, dans la mesure du possible, avec des objets de même nature, synthèse rappelant les caractères essentiels de l’objet étudié.

Pour l’analyse dirigée et la synthèse, le maître, au début de l’année, introduira dans ses questions les principaux termes de la réponse; dans la suite, les questions ne renfermeront plus qu’un terme de la réponse et finalement, elles ne renfermeront plus aucun élément de la réponse.

Causeries générales: tenue en classe, à l’église, à la rue, au village, relations avec les compagnons, règlement scolaire, personnes, choses, scènes du milieu immédiat; premières notions de politesse.

Hygiène: propreté du corps et des vêtements, propreté de la classe, de la cour, de l’habitation et de ses environs, soins à donner aux organes des sens, précautions à prendre et choses à éviter en ce qui les concerne.

Les causeries et les leçons d’hygiène seront traitées comme des leçons d’élocution. En règle générale, le maître commencera par un exposé concrétisé et dramatisé. Il choisira l’exemple d’un enfant, qui deviendra le héros de tous ses récits et qui constatera et fera ce qu’il veut que les élèves constatent et fassent. Il multipliera les péripéties de façon à donner à ses récits un intérêt toujours nouveau. Après le récit, il procédera à l’analyse et à là synthèse en graduant ses questions comme pour les leçons d’intuition.

Dessin: Point; ligne droite, horizontale, verticale, oblique, combinaisons diverses; dessin simplifié et d’après nature d’objets divers: barrière, table, chaise, lance, couteau, drapeau, machette, etc…

Chants: petits chants appris par audition.

Gymnastique: marche rythmées avec ou sans chant, jeux.

Français: (cours facultatif) noms des objets de la classe, d’objets usuels, verbes les plus communément employés, conjugaison de ces verbes à l’indicatif présent. Pendant les leçons de français, il est désirable de ne pas recourir aux traductions; le maître doit montrer, agir et parler, faire montrer, faire agir et faire parler.

Travaux manuels: cultures, élevage, métiers indigènes, constructions et réparations exécutées avec le concours d’élèves.

DEUXIEME ANNEE D’ETUDES.

Religion: programme à déterminer par les autorités religieuses.

Lecture: lecture courante. Comme en 1re année d’études, les exercices de lecture sont combinés avec des exercices d’écriture et l’étude de l’orthographe.

Langue maternelle: notion du nom, du verbe, de l’adjectif.

Calcul: étude des nombres de 1 à 20; additions, soustractions multiplications, divisions; la douzaine; petits problèmes oraux et écrits, chiffres romains.

Système métrique: litre, franc, kilogramme, décamètre, décalitre, billets de 5 et de 20 frs; décimètre, décilitre; décime nombreux exercices pratiques: mesurages, pesages, paiements; petits problèmes oraux et écrits.

Leçons d’intuition: plantes, fleurs, fruits, animaux, outillage et produits indigènes. La marche à suivre pour ces leçons est la même que celle indiquée dans le programme de la 1re année d’études; au cours de la synthèse, un petit résumé est écrit au tableau. Ce petit résumé est copié par le et peut servir de base à une série d’exercices.

Causeries générales: politesse: respect dû aux autorités civiles et religieuses; aide à donner aux vieillards et aux infirmes; douceur envers les animaux; accidents géographiques de la région, phénomènes naturels: jour, nuit, vent, pluie, éclair, tonnerre, etc.

Hygiène: habitation; aliments et boissons; précautions à prendre contre le soleil, contre le froid, avec le feu; notions générales sur les maladies tropicales les plus répandues dans la région; précautions à prendre pour les éviter.

Les causeries générales et les leçons d’hygiène se donnent de la même façon qu’en première année d’études. La synthèse de la leçon est écrite au tableau. Celle-ci se présentera sous forme d’un petit récit terminé par une conclusion pratique renfermant la notion que le maître a voulu enseigner.

Pour les accidents géographiques déjà connus des enfants et l’explication des phénomènes naturels, le maître peut aborder directement l’analyse. Au cours de celle-ci il rectifiera et complètera les connaissances des enfants. La synthèse de la leçon est également écrite au tableau.

Dessin: notion intuitive du carré et du rectangle; dessin d’après nature d’objets renfermant ces éléments: pavés, cadres, encadrements de portes, de volets, élévation d’une boîte, d’une armoire, etc.; dessin d’ornements simples dérivant du carré et du rectangle.

Chants: chants simples appris par audition.

Gymnastique: marches rythmées avec ou sans chant, jeux.

Français: (cours facultatif). Causeries sur des objets qui ont été analysés pendant les leçons d’intuition ou d’après tableaux. Les causeries sont suivies d’un résumé au tableau fait avec l’aide des élèves. Il faut profiter de ces résumés pour faire l’étude progressive de l’alphabet français: u, e, é, è, c, ç, g doux, j, q, gn, ai, ou, ou, om, an, am, in, un, um, au, eau, ent, ais, et, er, ez, ei, ail, euil, eil. Conjugaison des verbes à l’indicatif présent, au passé indéfini et au futur simple. Il convient généralement de faire conjuguer les verbes avec un ou plusieurs compléments d’après le degré d’avancement des élèves.

Travaux manuels: Développer le programme de la 1re année.

ECOLE PRIMAIRE DU DEUXIEME DEGRE

PREMIERE ANNEE D’ETUDES.

Religion: programme à déterminer par les autorités religieuses.

Lecture: lecture courante. Il est utile de faire précéder les leçons de lecture d’une petite causerie sur le texte à lire.

Langue maternelle: notion du nom, de l’adjectif, du pronom, du verbe, conjugaison des verbes.

Calcul: récapitulation des 20 premiers nombres; étude des nombres de 20 à 100; table de multiplication et division des 100 premiers nombres par les 10 premiers nombres; la centaine, le dixième, le centième; nombreux exercices et problèmes.Système métrique: mètre, décamètre, décimètre, hectomètre, centimètre, litre, décalitre, décilitre, hectolitre, centilitre; gramme, décagramme, décigramme, hectogramme, centigramme; franc, décime, centime, billets de 5, 20 et 100 frs: nombreux exercices pratiques mesurages, paiements; problèmes écrits et oraux.

Leçons d’intuition: outils de fabrication indigène et de fabrication européenne en usage dans le pays, métiers indigènes, causeries d’après tableaux. Pour les leçons d’intuition, la marche à suivre est la même que celle suivie à la deuxième année de l’école primaire du 1er degré. Le résumé peut être fait par les élèves au moyen de questions écrites au tableau au cours de la synthèse. Pour ces questions, on suivra la même gradation que celle qui a été adoptée pour les questions orales en 1re année d’études de l’école primaire du 1er degré.

Causeries générales: rôle des européens dans le pays, coutumes et pratiques du pays; politesse.

Hygiène: eau, qualités de l’eau potable, endroits où il faut la puiser, purification de l’eau; notions pratiques aussi complètes que le développement intellectuel des élèves sur la malaria, la maladie du sommeil, le pian, la variole, la fièvre récurrente.

Les causeries générales et les leçons d’hygiène se donnent comme à l’école primaire du 1ère degré, 2e année d’études. L’exposé concrétisé et dramatisé peut être accompagné d’expériences analogues aux constatations faites par le héros du récit: purification de l’eau; éclosion de moustiques, etc….

Les causeries sur les coutumes et les pratiques du pays supposent que le maître connaisse à fond la mentalité des indigènes de la région, leurs usages et toutes les pratiques superstitieuses et autres auxquelles ils se livrent. Le récit fera ressortir la valeur des coutumes et des pratiques utiles et le ridicule, l’inefficacité et éventuellement la nuisance des autres. Le résumé de ces leçons sera préparé de la même façon que les résumés des leçons d’intuition.

Géographie: classe, quatre points cardinaux, orientation de la classe, de l’école; environs de l’école; étude sommaire mais méthodique du territoire; croquis et cartes; histoire du territoire.

Agriculture: différentes espèces de terrains; caractéristiques, qualités, défauts, moyens à employer pour les améliorer; engrais verts et autres; préparation du terrain pour les semis et les plantations: disposition des parcelles.

Dessin: notion intuitive du carré, du rectangle, du triangle du losange; dessin d’après nature d’objets renfermant ces éléments; dessin d’ornements simples dérivant des éléments étudiés; frises décoratives.

Calligraphie: étude méthodique des minuscules.

Chants: chants simples appris par audition. Eventuellement quelques notions musicales théoriques: la gamme, l’accord parfait et son renversement tons, demi-tons, degrés; exercices de lecture sans et avec mesure, de solfège; dictées musicales; exercices de vocalise et d’adaptation de paroles.

Gymnastique: exercice choisis d’ordre et dérivatifs, extension et suspension, exercices d’équilibre, exercices pour la nuque, le dos, l’abdomen, exercices latéraux, marches, sauts, courses, exercices respiratoires et calmants.

Français: (cours obligatoire dans les centres dans les centres urbains, facultatif dans les autres centres) causeries d’après tableaux suivies de résumés faits avec les élèves. Notions de grammaire.

Travaux manuels: culture, élevage: métiers indigènes perfectionnés, collaboration aux travaux de construction et de réparation.

DEUXIEME ANNEE D’ETUDES.

Religion: programme à déterminer par les autorités religieuses.

Lecture: lecture expressive. Les textes à lire font l’objet d’une analyse sommaire très simple avant d’être lus.

Langue maternelle: étude du nom, de l’adjectif, du pronom, de l’adverbe, du verbe, études des préfixes, infixes et suffixes.

Rédaction: exercices de comparaison entre deux choses concrètes, petits récits puisés dans la vie des enfants ou dans l’actualité locale.

Calcul: les quatre opérations sur les 1.000 premiers nombres, recherches des 2/3, des 3/4, etc. d’un nombre; le millième; problèmes écrits et oraux, achats, ventes, gains, pertes.

Système métrique: récapitulation du programme de la 1re année du 2e degré; le kilomètre, le millimètre, le kilogramme; mesures de surface; périmètre et surface du carré et du rectangles.

Leçon d’intuition: produits de la culture, de la cueillette, de l’industrie locale; même marche que pour les leçons d’intuition en 1re année du 2e degré. Le résumé à faire par les élèves peut être préparé au moyen d’un canevas.

Causeries générales: les usages et les pratiques du pays: croyances superstitieuses; rôle néfaste des féticheurs; phénomènes naturels: foudre, grêle, tremblements de terre, éclipses; dangers que présentent la consommation de l’alcool, l’usage du chanvre et d’autres plantes stupéfiantes.

Hygiène: maladies de la peau, maladies du ventre, maladies de la poitrine; symptômes, causes, propagation, précautions, soins.

Pour les causeries et les leçons d’hygiène, on suit a même marche qu’en 1re année du 2e degré. Au cours de la synthèse, un canevas à développer par les élèves est écrit au tableau.

Géographie: révision du cours de 1re année; le globe terrestre, le soleil, la lune, les étoiles, le jour, la nuit, les cinq parties du monde, les grands océans, quelques grands voyages sur la sphère le Congo Belge; situation, limites, chefs-lieux; description du cours du fleuve Congo. Histoire de l’occupation du Congo par la Belgique.

Agriculture: cultures du pays, variétés à choisir, plantation, semis, soins des plantations, récolte. Choix des boutures ou des graines pour les cultures de l’année suivante; conservation et transformation des produits; culture des arbres fruitiers: variétés à choisir, greffage, soins; oiseaux utiles, oiseaux nuisibles; insectes nuisibles et leur destruction; culture des arbres et des plantes donnant les produits d’exportation; destruction des insectes et des animaux nuisibles.

Dessin: Le carré, le rectangle, le losange, l’hexagone, le cercle; dessin d’après nature d’objets renfermant les éléments étudiés; dessin d’après nature, de feuilles, de fleurs et de fruits; stylisation de ces éléments; frises ornementales.

Calligraphie: révision du cours de la 1re année, étude méthodique des majuscules.

Chants: quelques chants appris par audition à 1 et à 2 voix. Eventuellement continuation de la théorie musicale donnée en 11, année: tons, demi-tons, degrés de la gamme, etc., manière de prendre le ton à l’aide de formules; exercices de solfège, dictées musicales, exercices de vocalise et d’adaptation de paroles à la musique.

Gymnastique: mêmes exercices qu’en 1re année.

Français: (cours obligatoire dans les centres dans les centres urbains, facultatif dans les autres centres), causeries d’après tableau ou sur les objets analysés dans les leçons d’intuition suivies de résumés faits an tableau avec l’aide des élèves. Exercices sur notions de grammaire.

Travaux manuels: Programme de la première année à développer.

TROISIEME ANNEE D’ETUDES.

Religion: Programme à déterminer par les autorités religieuses.

Lecture: lecture expressive comme en 2e année d’études. Les analyses doivent être plus complètes qu’en 2e année.

Langue maternelle: Etude complète des parties du discours, compléments, analyse grammaticale. Rédactions: comparaisons entre deux choses concrètes, deux choses abstraites, petites descriptions, petits récits, lettres.

Calcul: les quatre opérations sur les nombres entiers et décimaux jusqu’au nombre 10.000: règle de trois simple et directe; recherche de l’intérêt: nombreux problèmes.

Système métrique: mesures de longueur, de capacité, de poids, monnaies; mesures de surface, mesures agraires; périmètre et surface du carré, du rectangle, du triangle; diamètre, circonférence et surface du cercle; nombreux exercices pratiques; nombreux problèmes.

Causeries générales: Principales stipulations du décret sur les chefferies; obligations des indigènes en matière de recensement, d’impôts, de milice; principales dispositions législatives sur les armes à feu, la chasse, l’alcool, le chanvre, les jeux de hasard.

Hygiène: révision des notions enseignées dans les quatre premières années; premiers soins en cas d’accident – asphyxie, hémorragie, brûlure, empoisonnement, syncope, morsure de serpent, foulure, fracture; quelques notions d’asepsie et d’antisepsie; soins des plaies; maladies vénériennes.

Les causeries générales et les leçons d’hygiène sont résumées au tableau. Ce résumé est transcrit par les élèves dans un cahier spécial et doit être étudié de mémoire.

Géographie: révision des matières enseignées dans les cours inférieurs; étude méthodique du district: cours d’eau, production, centres, voies de communication, industrie, commerce, grandes tribus, divisions administratives, missions; quelques notions sur la Belgique: situation, quelques villes, fleuves, chemins de fer (longueur) quelques indications sur la richesse et l’activité du peuple belge la famille royale de Belgique.

Agriculture: révision du cours donné dans les deux années précédentes; petit bétail, éventuellement gros bétail, animaux et oiseaux de basse-cour; soins, maladies, remèdes, nourriture, choix des reproducteurs; conditions que doivent réunir les étables, les clapiers, les poulaillers, les pigeonniers; traitement des produits.

Dessin: plan-détaillé d’une case modèle, d’une porte, d’une fenêtre, d’une table, d’une chaise, d’un banc, d’un lit, d’une armoire; matières colorantes existant dans la région et pouvant servir à la décoration de la case.

Calligraphie: minuscules et majuscules; écriture grande, moyenne et petite.

Chant: chants à une et à deux voix appris par audition. Eventuellement développement du cours théorique donné en 2e année.

Gymnastique: leçons comme en Ile année d’études.

Français: (cours obligatoire dans les centres dans les centres urbains, facultatif dans les autres centres): causeries d’après tableaux ou sur des choses concrètes, petites rédactions. Exercices écrits portant spécialement sur les notions de grammaire et sur l’orthographe.

Travaux manuels: Programme de la deuxième année à développer.

Dans les écoles de filles l’on peut suivre le même programme que dans les écoles de garçons. L’on y ajoutera toutefois des notions aussi complètes que possible de puériculture à donner en 3e année du 2e degré, ainsi que les travaux à l’aiguille.

Le programme suivant pourrait être adopté pour ces travaux:

1re année du 1er degré: points devant, de piqûre, de cordonnet, à la croix sur gros tissus en tirant un fil; quelques travaux en raphia et tricot à 2 aiguilles: montage du tricot, mailles à l’endroit, à l’envers, etc.

2e année du 1er degré: points devant, de piqûre, de cordonnet, à la croix sur tissus moins gros que ceux employés en 1re année et sans tirer un fil; quelques travaux en raphia et tricot à 2 aiguilles.

1re année du 2e degré: points de piqûre, devant et de côté sur plis rentrés; tricot à 4 aiguilles: étude de la chaussette; travaux d’agrément.

2e année du 2e degré: points de surjet, de feston, de flanelle; travaux d’agrément; tricot à 4 aiguilles: études du bas, ravaudage et manière de renforcer le tricot.

3e année du 2e degré: point de boutonnière, fixation des boutons, oeillets, agrafes, pressions; tracé, coupe et confection de vêtements simples; tricot; rempiétage du bas, ravaudage, remmaillage, tricot d’une brassière, de chaussons de bébés etc.

NOTE

[i] Conçus comme ils le sont, les programmes paraissent applicables dans toutes les écoles. En cas de nécessité, il sera néanmoins permis de s’en écarter. Us inspecteur du Gouvernement, d’accord avec les missionnaires-inspecteurs, décideront des changements à apporter éventuellement au Programme. Ils veilleront toutefois à ce que les modifications n’aillent pas jusqu’à faire disparaître certaines branches du programme ou à diminuer notablement l’ensemble des matières à enseigner.

Appendix 9 – Letters from Pierre Kolokoto to Paul Jans, from the Aequatoria Archive Transcribed from the microfilms.

Beambo le 8 octobre 1935

Très R. Père Paul Jans

J’ai l’honneur de vous faire connaître que tous les gens de Bofidji ont déjà payé l’impôt. Mais exceptez moi, donc tâchez de m’envoyer 70 frs. de mon salaire.

Je vous envoie mon livret du travail parce que je n’ai pas encore toucher le moi de septembre à cause que je suis très éloigné. Je vous demande aussi 20 frs. que vous avez promis à mes élèves pour leurs nourritures. Alors il ne faut pas oublier de m’envoyer la couverture que vous m’avez promise de l’année 1935, parce que vous n’avez pas donné.

Donc envoyez moi aussi un rideau pour la classe, un pacquet de craies, un paquet de touches aussi que qq cahiers pour les journaux de classe.

Veuillez agréer très R. P. Paul, les salutations très cordiales de votre serviteur,

Kolokoto Pierre, moniteur de l’école rurale Beambo.

—

2.

Beambo le 29 octobre 1935

J’ai l’honneur de vous faire savoir que je suis en bonne santé ainsi que mes élèves, mais quelques uns ont des plaies donc ils manquent seulement des médicaments. J’ai bien reçue la lettre dont vous m’avez evoyée par mes élèves avec 1 paquet de craies, 1 paquet de touches, 5 cahiers comme journal de classe ainsi que mon salaire 70 frs.

Excepter un rideau pour la classe – ainsi que la couverture promise par le R. Père Paul Jans, parce que la première est morte depuis 1934.

Très Révérend Père Supérieur, voilà une chose que je me regrette maintenant; j’ai engagé une femme puis j’ai donné à ses parents trois cents frs. et maintenant elle est à son village on demande encore quatre cents ou cinq cents frs pour compléter huit cents frs. donc je vous prie s’il vous plaît prêtez moi cinq cents ou quatre cents frs. donc vous retiendrez 50 frs. de ma salaire chaque fois car j’envoie mon livret ainsi vous ferez comme bon-pour dans mon livret.

Ne me refusez pas de me prêter parce que le moniteur de Indjolo avait prêté cinq cents frs chez le Père Paul Jans donc nous sommes aussi des moniteurs alors car j’ai une affaire s’il vous plaît aidez moi. Moi je recevrai seulement 20 frs. puis 50 frs. pour bon-pour jusque le bon-pour sera terminé. Donc je vous envoir mes élèves avec mon livret ainsi que 17 ardoises qui ne sont pas bonnes pour vous montrer. N’oubliez pas un rideau de la classe chez les Soeurs.

Donc quant à ma classe. Ca va bien, nous avons un grand jardin, très propre et bien arranger. Nous avons planté des bananiers, des maniocs doux, des ananas, des arrachides d’avec des palmiers. Donc dès que vous serez ici, vous verrez tous ça.

Veuillez agréer, très R. Père Supérieur, les salutations cordiales de votre seriteur.

Kolokoto Pierre, moniteur de l’école rurale de Beambo Bofidji Ouest

—

Beambo, le 4 décembre 1935

Très R. Père Supérieur

J’ai l’honneur de vous faire cette petite lettre.

Quant à la fiancée elle n’est pas dans ma maison. Mais elle est toujours au village natal, je n’ai pas assez de l’argent pour qu’elle viens dans ma maison, ses parents me demandent 1000 frs donc j’ai remis seulement 250 frs la dotte pas encore assez, comme je vous ai écri de vous m’envoyer 400 frs ce pour compléter la dotte, alors comment le catéchiste parle que moi je montre le mauvais exemple. Est-ce qu’elle dans ma maison? Si j’avais au moins 7000 frs la femme serais dans ma maison puis je l’enverrais au même instant à la mission, parce que nous avons l’obligation qu’un moniteur ne peut pas rester avec une femme car il ne pas encore marié avec.

Aussi nous ne pouvons pas envoyer une femme à la mission car la dotte pas encore terminé, sinon nous aurons toujours des difficulté contre ses parents, on me dira aussi que je suis un voleur.

Quant au catéchiste il n’est pas content de moi. Un jour il m’a demandé: comment les missionnaires ne donnent pas de l’argent aux catéchistes alors ils donnent seulement aux moniteurs. Donc pour cela il n’enseigne pas encore comme avant. deux semaines à la forêt pour chercher des copals copaux. trois semaines à la forêt pour la chasse puis les chrétiens prient seulement eux-mêmes quand il vient de la forêt seulement pour fabriquer des liriques. il dit où aurais-je de l’argent pour donner aux massons? je fréquenterai à la forêt pour chercher du copal.

Maintenant il a un fils donc son fils en ai une femme. le catechiste même qui a remsi la dotte puis ils sont dans sa maison même est-ce qu’ils sont mariés ils sont restés pendant 8 mois. Pourquoi il ne l’envoie pas à la mission tous les chrétiens de Beambo ne sont pas content de lui à cause qu’il ne reste pas au village toujours à la forêt. La chapelle que le Père Moeyens avait laissé la ….. (?), pas encore finit depuis 11 mois on prie seulement à sa maison. Sa femme dispute toujours contre les élèves, à cause de le jardin des élèves même; elle avait coupé un régime de banane puis les élèves sont encore contre moi donc moi je dis je dirai au père Supérieur.

Maintenant j’ai déjà commencé l’examen malgré s’il n’avais pas l’examen je serais à Bamanya immédiatement donc je viendrai après l’examen. Je serai à Bamanya 22 décembre.

Je vous envoie aussi mon livret pour le mois de novembre.

les salutations cordiales

le votre serviteur

Kolokoto Pierre

—

4.

Beambo, le 16 février 1936

J’ai l’honneur de vous faire connaître que je suis en bonne santé ainsi que mes élèves. Pour la classe les élèves sont très contents ainsi que leurs parents, parce que j’ai resté encore ici avec leurs fils, mais les élèves de deuxième année d’études nous demandent des livres (2e partie) pour chaque élève, ainsi que des cahiers de devoir, un livre de manuel français pour les apprendre un peu le français (lecture).

Quant au moniteur > Quant à moi. envoyez moi un paquet des craies, un paquet des touches, un carnet pour la liste d’appel pour cette année. Mais n’oubliez pas un rideau pour couvrir le tablau, parce que comme j’enseigne 2 classes il faut un rideau 2,5 m de largeur et 1,5 m de hauteur.

Mais avant tout cherchez mon livret de travail que le Père Paul m’a donné. J’ai diplômé en 1934 donc le Père Paul m’avait donné 60 frs. par mois, puis en 1935 il m’a donné 70 frs par mois parce que nous avons l’augmentation de 10 frs. par ans jusqu’à la fin de notre contrat, mais si vous doutez regarder dans mon livret que le Père Paul m’a donné, il vous montrera tous. Donc pour cette année 1936 vous m’avais donné 35 frs. donc il reste 45 frs. pour compléter 80 frs. du mois de janvier.

Je vous demande aussi l’argent du mois de février parce qu’il me reste 13 jours puis je suis très éloigné donc il faut que vous m’envoyez aussi. Je vous envoie mon livret par le fils du catéchiste. Maintenant moi et le catéchiste nous sommes d’accord pour le moment depuis la fête jusqu’à’maintenant.

Donc pour les deux mois que vous avez retenu, envoyez moi l’argent d’un mois parce que nous voulons payer l’impôt. Tous les gens de Bofidji sont allés à la forêt pour chercher le copal mais tâchez de m’envoyer l’argent pour l’impôt 55 frs. On paye 55 frs. pour tous les gens de Bofidji.

Votre serviteur

Kol.

Appendix 10 – Letters from Hilaire Vermeiren to Paul Jans, from the Aequatoria Archive Transcribed from the microfilms.

1.

Bokote, 19/1/1930

Beste Paul,

Zooals ik aan broeder Medard geschreven heb, houd ik Hilario achter. Ik had er wat moeite mee na het ontvangen van de magnifieke papieren van dit heerken, maar nu kan ik het met gerusten harte doen. Dat heerken heeft hier de revolutie gestookt. Ten anderen ik ben niets tevreden over die kornuiten. Zij hebben hier mijn schoolkolonie opgemaakt, dat het een schande is. Zij vertelden niets anders dan dat ze hier veel te veel moesten werken, geen eten kregen, en dat onze moniteurs stommerikken waren, waar niets bij te leeren viel. Dat laatste is wel waar, maar dat moeten die snotneuzen toch niet komen vertellen. Ik heb er dan ook met de zweep nogal opgezeten en als ze nog ooit op vacantie komen dan zullen ze de varkenskoten mogen schoon maken en als ze roespeteren kunt ge ze den volgenden keer zonder billen verwachten. …

Paul, jongen, ik beschouw dat als een gebrek in de opvoeding; de jongens hier in Bokote zijn uiterlijk minder gedisciplineerd, dat geloof ik wel, maar innerlijk zijn ze beter, ze hebben het niet achter de mouw, steken ze schavuitenstreken uit, ik rammel ze ne keer op hun gat en zij en ik zijn content. Dat systeem van band honderij (sic) is de pest van al onze opvoedingsscholen in België en ik zie dat ze dat vervloekte systeem naar Congo overbrengen. Daar is maar één man die het heeft aangedurfd aan ons klein liefdewerk daar verandering in te brengen, namelijk de dikke Piet en die heeft het ook moeten bekoopen, die zetelt nu als surveillant perpetuel in de studie. Gij hebt dat willen veranderen en ik ook en we zitten in de Congo; sans rancune voor die wijze en vroede vaderen, maar ik citeer de feiten zooals ze zijn. Als ge er iets aan kunt doen, Paul, laat van deze mannekens geen muilezels maken.

2.

Bokote, 10/5/31

Beste Paul,

In de gauwe gauwte enkele woordjes. Ik stuur u vier jongens. … van een heiden, Joannes Yembe. Deze laatste is hier zoowat moniteur geweest. Misschien kan hij wat meer … (?) bijkrijgen in Bamania; Niettegenstaande zijn rotte plakpooten is de man toch nog al met hart en ziel de zwakke sexe toegedaan. Voldoet hij niet, stuur hem dan maar als postcollie naar zijn dorp. Ik geef hem hierbij nog een kans. Verder J. Bolenge blijft hier. Nauwelijks aangekomen had hij het al verkorven. Een jonge meid kreeg drie armbanden, oorbellen, … Belangeloze vriendschap. Bomandeke Jean en Ifaso Hilario heb ik ne keer de les gelezen. Als ze nog zoo doen een volgende maal dan kunnen ze hier ook blijven. Dat is zoo wat alles, Paul, ik zit tot over mijn oren in het werk. Binnen enkele dagen zijn hier 110 doopsels.

Hilaire.

3.

Bokote, 6/6/31,

Beste Paul,

Brief wel ontvangen. Ik had gedacht met het lange wegblijven van de boot gelegenheid te hebben om een flink antwoord te sturen. Helaas; ik heb zo wat gesukkeld en dan is het er bij gebleven. Ik denk dat al de jonge heerkens van Bokuma terug naar Bamania gaan. Heer Yembi kan u gerust zonder gewetenswroeging ontslaan van verdere ontwikkeling zijner geestesvermogens: ik heb hem een laatste kans willen geven; indien hij niet voldoet volgend trimester, geef hem dan den bons, maar zend hem bid ik u naar de regionen van Wafanya, dat is de plaats waar zijn wiege stond. Dat de jongens van Bokuma erg ingebeeld zijn, concedo, maar ze hebben het potver hier niet gekregen: waar ze het gehaald hebben, weet ik niet, maar ze hebben het van hier naar ginder niet meegebracht. … Ik heb ze hier aan het potten van den oven gezet; werk dat hun nobele handen zeker lang niet meer verricht hadden. Kon het zijn dat die heerkens hier nooit meer kwamen onder de vacantie, ik zou mij en onzen missiepost gelukkig achten. De twee exemplaren die hier gebleven zijn moet ik minstens om de maand afranselen. … Enfin, zooals ge zegt het is een crisis en heel de Congo zal die crisis wel meemaken vooral omdat een neger van nature al erg ingebeeld en met zijn eigen zich zelven gauw tevreden is.

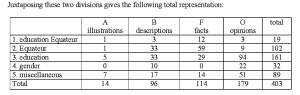

Appendix 11 – Contextual analysis of “La Voix du Congolais”

A short explanation of the method used in the analysis of La Voix du Congolais.

The collection I consulted is almost complete, with only seven issues missing. Only three of the six issues were available from the first year (so the period March-August 1945 is missing). Issue 13 from 1947 and issue 26 from 1948 are also missing. No other issues are missing from the following years, although some numbers are not stated in the summary tables I made because there was no information of interest to us in those issues. Issues 159 and 162 from 1959 are also missing.

During the first reading of these issues a record was taken of the articles, references, photographs, opinions, etc. that fulfilled our selection criteria. These selection criteria can be summarised relatively clearly and simply: anything, in the broadest sense, relating to education, the Equateur province and/or the congregations active in the vicariate of the MSC. This first selection resulted in approximately 450 references.

In a second phase these references were copied, in which another verification was carried out with regard to the subject and the extent to which it complied with the criteria. After this, over 400 references remained and the corresponding documents were copied. The remaining documents were marked with an X.

In a third phase the copies taken were subdivided into four main groups. This division was based on the type of text. The division consists of the following four themes:

A: Illustrations (photographs)

B: Descriptive (or mostly descriptive) contributions, in which the emphasis was on the representation of situations, places, conditions, rather than on the representation of an opinion on that subject.

F: Factual information, not descriptive or narrative documents but those contributions that gave statistical or factual information.

O: Opinion. Those contributions in which the author put forward a particular opinion.

Naturally, all the documents cannot be simply allocated to one of these groups. If they overlapped I opted to only allocate them to a single group on the basis of the predominant element. With regard to the first group, it then relates to those documents that were only kept for the illustrations or which are only made up of an illustration. This is also the smallest group.

On this basis we obtained the following subdivision:

A: 14

B: 96

F: 114

O: 179

These four groups were then subdivided again into five thematic groups. The following themes were defined in this:

1: Education and Equateur

2: Equateur

3: Education

4: Gender

5: Miscellaneous

Quantitatively this gives the following:

Group 1: 19 documents

Group 2: 102 documents

Group 3: 161 documents

Group 4: 32 documents

Group 5: 89 documents

Juxtaposing these two divisions gives the following total representation:

A few very general remarks have to be made: firstly the group “illustrations” is the smallest group. However, a large number of illustrations were also in the other categories, which were then not explicitly counted. A number of subjects presented to the reader over numerous issues are included in categories B and O. Each issue was maintained as such and counted as a single item. The largest subcategory was that of the opinion documents on education (general). This indicates that it was worth using the source. Naturally, the smallest of the contextual groups is that on education in the Equateur province. That is not illogical as it relates to a theme that was delineated following multiple criteria, and the periodical had to consider a lot of themes for the entire colony.

The category “miscellaneous” should perhaps be clarified: this still relates to subjects relating to education and Equateur but those that are broader or related but situated within the context of the research. With illustrations this mainly relates to school photographs or photographs of specific people. In opinion articles it may, for example, relate to “évolués”. In the factual information it may relate to a contribution on authority or a speech by the governor general. I really only distilled the fourth category in the second instance from this miscellaneous category because it proved to be a relatively large body of material (particularly opinion documents) on the education / civilisation / development of woman in Congolese society.

In the final phase each document was given a concise commentary at the very least (both regarding the photographs and the longer documents) and in a number of cases literal information was also copied from them. All references were copied into an Excel file at that point, with a short reference to the title, subject and, if given, the author. Every contribution was given its own coding, which consisted of the year, page number and category codes to which the contribution belonged. In a small number of cases there were some documents with exactly the same code. The starting page was then used to distinguish between these.

Appendix 12 – The history of the emergence of schools in the Equator province, by Stephane Boale (The text has been copied word-for-word from the written document.)

Création des écoles de village

L’origine des écoles dites de village se situe vers 1880. C’était fait par les premiers missionaires Trappistes chez les Mongo du tribu Mbole, Bosaka, Nkole, Bolukutu et Bakutu, lesquels se trouvent sur les 5 rivières Luafa, Lomela, Busira, Salonga et Momboyo (voir la carte de la province de l’Equateur), autrement appelé la région de l’Equateur Sud.

L’esquisse de cette historique rempli d’enseignements, nous l’avons reçue grâce à monsieur Boale Stéphane du village de Momboyo monEnE, secteur Dzera, du territoire de Boende, district de la Tshuapa, province de l’Equateur Sud. L’intéressé est diplômé de l’école normale de Bamanya, ancien commis de l’Etat au service de la météorologie du Congo Belge, pour lequel il a effectué beaucoup de stages à l’étranger, ce qui lui a fourni une bagage de formation solide. Et compte tenu de ce qui vient de nous être revelé, l’intéressé veut nous livrer ses impressions sur l’histoire de l’école de village, lui léguées par ses ancêtres et les vieux du village qui y véçurent dès l’arrivée des blancs, missionnaires trappistes vers les années 1890. Ils étaient venus pour l’évangélisation du Congo Belge, afin que tous les Congolais, hommes et femmes, pourraient être baptisés, selon la mission leur confiée par S.M. le Roi Léopold II.

Ce qui fut fait. C’est ainsi que les prêtres de la congrégation des Trappistes ont répondu vivement à l’appel lancé par le Roi Léopold II à desservir le bassin du Congo, particulièrement la sous-région de l’Equateur, pour ainsi collaborer à l’évangélisation de ce peuplade.

Dès leur arrivée à l’Equateur (Mbandaka) les premiers missionnaires ont fondé leur première mission à Mpaku, en amont plus ou moins trois kilomètres de la ville de Mbandaka. Malheureusement, à cause de l’état malsain du lieu, ils ont du se déplacer pour fonder une nouvelle mission à Boloko wa Nsimba, plus près de la ville de Mbandaka, et vers la mission protestante de Bolenge. Et ensuite le fondement de missions ne devrait pas se limiter qu’au centre de la ville de Mbandaka, mais a été transféré à travers les 5 rivières cités ci-haut. Voici la liste des missions catholiques fondées par les prêtres Trappistes:

Boloko wa Nsimba

Bamanya

Bokuma

Boteka

Imbonga

Wafanya

Bolima

Bokote

Bokela

Boende

Bokungu

Ikela

Comment devaient-ils évangéliser un peuple dont ils ne connaissaient ni la langue, ni la culture, ni les moeurs? Autant de questions furent posées à qui veut l’entendre. Mais sachez que Jésus Chrtist avait dit à ses disciples que “je ne vous laisserai pas orphélins, je serai avec vous tout le temps (par l’esprit)”. A ce dire, les missionaires Trappistes étaient convainçus que tout irait selon les paroles du Christ. La meilleure méthode de communication employée par les Trappistes auprès du peuple Mongo était celle de la pédagogie appliquée avec persuasion, car il n’y avait pas seulement l’enseignement de la parole de Dieu, mais aussi celui de l’écriture (alphabet) lesquelles devaient aller de pair pour une bonne compréhension et une réussite totale des enseignements donnés. “Les paroles s’envolent, mais l’écriture reste” dit-on. D’où est né l’école du village. L’école du village créé par les missionaires Trappistes n’était pas une école en soi, mais un système inventé par eux-mêmes afin de permettre aux catéchumènes que la combinaison de l’Evangile enseigné et l’écriture apprise pourraient leur donner des bons fruits à la récolte, suite à la qualité de l’enseignement donné et son appréciation par ceux qui l’écoutaient. Connaissance de la langue Lomongo (ou Lonkundo): c’est la seule que tout le peuple Mongo parle, de la mission Boloko wa Nsimba, passant par toutes les missions citées ci-haut. Elle est parlé dans son ensemble par les Mongo du Sud de l’Equateur.

Les prêtres Trappistes se sont efforcés, graduellement, et peu à peu, avec assurance à l’étude de la langue Mongo, et sont arrivés à balbutier l’Evangile dans cette langue, dont le recrutement des catéchistes et quelques jeunes de bonne volonté dépendait, car le nombre de pères Trappistes n’était pas suffisant pour ainsi affluer dans toutes les missions. C’est ainsi qu’il faut repartir tous sortants de l’école du village pour ainsi suppléer à la pénurie des prêtres et les épauler dans cette noble mission, en attendant l’arrivée, de l’Europe, d’autres prêtres. Lorsque l’enseignement de l’écriture a été reconnu par son importance et sa viabilité auprès de la jeunesse montante, il a permis à tout le monde sans exception, de se faire instruire et baptiser, pour ainsi tirer les bénéfices collosaux de la connaissance de l’écriture. C’est ainsi qu’il y avait beaucoup de croyants qui ont abandonné leurs coutumes afin de servir Dieu qui incarne l’écriture (magie), qui a permis une communication facile avec ceux qui sont loin de nous.

Prise de l’école du village par l’Etat.

Par les rapports que les catéchistes adressent auprès des curés de chaque mission, parlant de leurs activités dans la mission, spécialement tous les activités de l’école de village, celles-ci ont retenu l’attention des responsables des missions. Alors ces derniers ont instruit l’autorité de l’Etat de cette situation préoccupante et promettante pour l’avenir du Congo Belge. Il a été décidé par l’autorité compétente la création des écoles rurales et primaires subsidiées par l’autorité de l’Etat, en engeagant les moniteurs, lesquels seront sous l’autorité des missionaires. Ainsi est né les écoles rurales et primaires avec un programme imposé par l’Etat et non comme était l’école du village sans programme. L’Etat devait à peine s’occuper de l’enseignement, lequel devait être suivi par les inspecteurs sur toutes les normes dictées par l’Etat.

(transcription du document rédigé par Stéphane Boale, rendu à l’auteur le 27 Octobre 2003.)

Appendix 13 – “Extrait de la causerie du Ministre des Colonies, M. Jules Renquin avec les premiers missionnaires catholiques du Congo-Belge” [Extract from a talk given by the Minister for the Colonies, Mr Jules Renquin, to the first Belgian Catholic missionaries to the Belgian Congo]. The text was acquired from Jean Indenge, Brussels, November 2003

« EXTRAIT DE LA CAUSERIE DU MINISTRE DES COLONIES, M. JULES RENQUIN EN 1920 AVEC LES PREMIERS MISSIONNAIRES CATHOLIQUES DU CONGO-BELGE.

Les devoirs des Missionnaires dans notre Colonie

Révérends Pères et Chers Compatriotes,

Soyez les bienvenus dans notre seconde patrie, le Congo-Belge.

La tâche que vous êtes conviés à y accomplir est très délicate et demande beaucoup de tact. Prêtres, vous venez certes pour évangéliser. Mais cette évangélisation doit s’inspirer de notre grand principe: tout avant tout pour les intérêts de la métropole (Belgique).

Le but essentiel de votre mission n’est donc point d’apprendre aux noirs à connaître DIEU. Ils le connaissent déjà. Ils parlent et se soumettent à un NZAMBE ou un MVIDI-MUKULU, et que sais-je encore. Ils savent que tuer, voler, calomnier, injurier … est mauvais.

Ayant le courage de l’avouer, vous ne venez donc pas leur apprendre ce qu’ils savent déjà. Votre rôle consiste essentiellement à faciliter la tâche aux administratifs et aux industriels. C’est donc dire que vous interpréterez l’évangile de la façon qui sert le mieux nos intérêts dans cette partie du monde.

Pour ce faire, vous veillez entre autre à:

1° Désintéresser nos “sauvages” des richesses matérielles dont regorgent leur sol et sous-sol, pour éviter que s’intéressant, ils ne nous fassent une concurrence meurtrière et rêvent un jour à nous déloger. Votre connaissance de l’évangile vous permettra de trouver facilement des textes qui recommandent et font aimer la pauvreté. Exemple: “Heureux sont les pauvres, car le royaume des cieux est à eux” et “il est plus difficile à un riche d’entrer au ciel qu’à un chameau d’entrer par le trou d’une aiguille”. Vous ferez donc tout pour que ces Nègres aient peur de s’enrichir pour mériter le ciel.

2° Les contenir pour éviter qu’ils ne se révoltent. Les Administratifs ainsi que les industriels se verront obligés de temps en temps, pour se faire craindre, de recourir à la violence (injurier, battre …) Il ne faut pas que les Nègres ripostent ou nourrissent des sentiments de vengeance. Pour cela, vous leur enseignerez de tout supporter. Vous commenterez et les inviterez à suivre l’exemple de tous les saints qui ont tendu la deuxième joue, qui ont pardonné les offenses, qui ont reçu sans tressaillir les crachats et les insultes.

3° Les détacher et les faire mépriser tout ce qui pourrait leur donner le courage de nous affronter. Je songe ici spécialement à leurs nombreux fétiches de guerre qu’ils prétendent les rendre invulnérables. Etant donné que les vieux n’entendraient point les abandonner, car ils vont bientôt disparaître: votre action doit porter essentiellement sur les jeunes.

4° Insister particulièrement sur la soumission et l’obéissance aveugles. Cette vertu se pratique mieux quand il y a absence d’esprit critique. Donc évitez de développer l’esprit critique dans vos écoles. Apprenez-leur à croire et non à raisonner. Instituez pour eux un système de confession qui fera de vous de bons détectives pour dénoncer tout noir ayant une prise de conscience et qui revendiquerait l’indépendance nationale.

5° Enseignez-leur une doctrine dont vous ne mettrez pas vous-même les principes en pratique. Et s’ils vous demandaient pourquoi vous vous comportez contrairement à ce que vous prêchez, répondez-leur que “vous les noirs, suivez ce que nous vous disons et non ce que nous faisons”. Et s’ils répliquaient en vous faisant remarquer qu’une foi sans pratique est une foi morte, fâchez-vous et répondez: “heureux ceux qui croient sans protester”.

6° Dites-leur que leurs statuettes sont l’oeuvre de Satan. Confisquez-les et allez remplir nos musées: de Tervurene, du Vatican. Faites oublier aux noirs leurs ancêtres.

7° Ne présentez jamais une chaise à un noir qui vient vous voir. Donnez-lui tout au plus une cigarette. Ne l’invitez jamais à dîner même s’il vous tue une poule chaque fois que vous arrivez chez lui.

8° Considérez tous les noirs comme de petits enfants que vous devez continuer à tromper. Exigez qu’ils vous appellent tous “mon père”.

9° Criez au communisme et à la persécution quand ils vous demandent de cesser de les tromper et de les exploiter.

Ce sont là chers Compatriotes, quelques-uns des principes que vous appliquerez sans faille. Vous en trouverez beaucoup d’autres dans des livres et textes qui vous seront remis à la fin de cette séance.

Le Roi attache beaucoup d’importance à votre mission. Aussi a-t-il décidé de faire tout pour vous la faciliter. Vous jouirez de la très grande protection des Administratifs.

Vous aurez de l’argent pour vos oeuvres Evangéliques et vos déplacements.

Vous recevrez gratuitement des terrains de construction pour leur mise en valeur, vous pourrez disposer d’une main d’oeuvre gratuite.

Voilà donc Révérends Pères et Chers Compatriotes, ce que j’ai été prié de vous faire savoir en ce jour.

Main dans la main, travaillons donc pour la grandeur de notre Chère Patrie.

Vive le Souverain,

Vive la Belgique.

Source: Avenir colonial Belge, 30 octobre 1920, Bruxelles.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Literature

A

Ackers, J. en Hardman, F. (2001). Classroom interaction in Kenyan Primary Schools. In Compare, XXXI, 2, p. 246-261.

Alban, [Frère] (1970). Histoire de l’institut des frères des écoles chrétiennes. Expansion hors de France (1700-1966). Rome: Frères des Ecoles Chrétiennes. p. 641-643.

Altbach, P.G. & Kelly, G.P. (eds.) (1984). Education and the colonial experience. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Ancelot, H. (1954). Coquilhatville 1954: en parcourant les quartiers de la ville. In L’actualité congolaise. Edition B, n° 209, p. 1-2.

Anstey, R. (1966). King Leopold’s legacy: The Congo under Belgian rule 1908-1960. London: Oxford University Press.

Arens, B. (1925). Manuel des missions catholiques. Leuven: Museum Lessianum.

Arnaut, K., Bulcaen, C., Vanhee, H. & Kerstens, P. (2003). Driemaal Verlinden: het drama van een journalist-historicus.

At http://cas1.elis.rug.ac.be/avrug/pdf02/verli_01.pdf (and 02, 03, 04).

Asselberghs, H. & Lesage, D. (1999). Globalisering als neokolonialisme. Inleiding bij een catalogus voor een mogelijk museum. In id. (ed.), Het museum van de natie. Van kolonialisme tot globalisering. Brussel: Gevaert.

Austen, R.A. & Headrick, R. (1983). Equatorial Africa under Colonial rule. In Birmingham, D. & Martin, P.M. (eds.), History of Central Africa. London/New York: Longman. vol. 2. p. 27-94.

B

Balagopalan, S. (2002). Constructing indigenous childhoods: colonialism, vocational education and the working child. In Childhood: a global journal of child research, IX, 1, p. 19-34.

Balegamire, Bazilashe J. (1989). Scolarisation, exode rural et nouveaux critères d’ascension sociale au Zaïre. In Genève-Afrique, XXVIII, p.77-86.

Barringer, T. (2000). Why are missionary periodicals (not) so boring? The Missionary Periodicals Database Project. In African Research and Documentation, LXXXIV, p. 33-46.

Berman, E.H. (ed.) (1975).

African Reactions to Missionary Education. New York/London: Teachers College Press.

Beyen, M. (1998). Vlaamsch zijn in het bloed en niet alleen in de hersenen: het Vlaamse volk tussen ras en cultuur (1919-1939). In Beyen, M. & Vanpaemel G. (Eds.), Rasechte wetenschap? Het rasbegrip tussen wetenschap en politiek vóór de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Leuven: Acco. p. 173-201.

Beyens, A. (1992). L’histoire du statut des villes. In Congo 1955-1960: recueil d’études – Congo 1955-1960: verzameling studies. Bruxelles: ARSOM. p. 15-70.

Bickers, R.A. and Seton, R. (ed.) (1996). Missionary encounters, sources and issues. Surrey: Curzon Press.

Block, J.P. (1992). La guerre scolaire au Congo Belge sous Auguste Buisseret (1954-1958). Ses prémices et développements. Onuitgegeven licentiaatsverhandeling. Université Libre de Bruxelles.

Blommaert, J. (2001). Ex-shit Congo – Het No Man’s land van de Kongolese verbeelding. http://cas1.elis.rug.ac.be/avrug/exshit.htm (10/2004)

Blondeel, W. (1973).

Het evangelisatiewerk der katholieke missies binnen de kolonisatie van Kongo, 1876-1926. Detailstudie: Witte Paters en Broeders van de Kristelijke Scholen. Unpublished masters dissertation. University of Ghent.

Boelaert, E. (1939). De Nkundo-maatschappij. In Kongo-Overzee, VI, 1, p. 148-161.

Boelaert, E. (1953). Charles Lemaire: Premier commissaire du district de l’équateur. In Bulletin des Séances de l’Insitut Royal Colonial Belge, XXIV, p. 506-535.

Bolamba, A.R. (1950). Impressions de voyage. Coquilhatville. In La Voix du Congolais, VI, p. 212-214.

Bolamba, A.R. (1955). Coquilhatville en 1954. In La Voix du Congolais, XI, p. 88-105.

Bolela, A. (1971). Un aperçu de la presse congolaise écrite par les noirs de 1885 à 1960. In Congo-Afrique, XI, 20-21.

Bontinck, F. (1984). La genèse de la Convention entre le Saint-Siège et l’Etat Indépendant du Congo. In Revue Africaine de Théologie, VIII, p. 197-239.

Boonants, B. (1982). Het beeld van Belgisch Kongo in de geschiedenishandboeken van het middelbaar onderwijs in België, 1904 tot 1980. Onuitgegeven licentiaatsverhandeling. K.U. Leuven.

Boone, A.Th. & Depaepe, M. (1996). Over het wezen en de betekenis van de koloniaal-pedagogische traditie in België en Nederland. In Pedagogisch Tijdschrift, XXI, 2, p. 81-85.

Bormans, Y. (1984). Een Unilever plantagebedrijf in de Belgische Kongo: de Société des Huileries du Congo Belge, 1911-1938. Onuitgegeven licentiaatsverhandeling. K.U.Leuven.

Bosmans-Hermans, A. (1983). The international economic expansion of Belgium and the primary school (1905-1910). In Rozprawy z dziejów oswiaty, XXV, p. 179-186.

Boucquillon, C. (1983). Missionaire opvoeding in het lager en het kleuteronderwijs, 1945-1980. Een onderzoek van de opvattingen en het aanbod van het pauselijk missiewerk der kinderen. Onuitgegeven licentiaatsverhandeling. K.U. Leuven.

Boudens, R. (1989). De negentiende-eeuwse missionaire beweging. In Boudens, R. (ed.) Rond Damiaan. Handelingen van het colloquium n.a.v. de honderdste verjaardag van het overlijden van pater Damiaan 9-10 maart 1989. Kadoc Studies 7, Leuven: University Press. p. 16-39.

Boyle, P.M. (1995). School wars: Church, State and the death of the Congo. In The journal of modern African studies, XXXIII, 3. p. 451-468.

Bral, J. (ed.) (1984). De Mongo cultuur. De Mongo: bewoners van het Evenaarswoud in Zaïre (Tentoonstellingscatalogus). Brussel: Gemeentekrediet.

Brausch, G. (1961). Belgian administration in the Congo. London: Oxford University Press.

Briffaerts, J. (2004). Center and periphery as a framework for the history of colonial education. In Dhoker, M. & Depaepe, M. (ed.) (2004). Op eigen vleugels. Liber amicorum An Hermans. Leuven: Garant. p. 96-106.

Briffaerts, J. (2003). De rol van de staat in de onderwijsorganisatie in Belgisch Kongo (1908-1958). In Boekholt, P., Van Crombrugge, H., Dodde, N.L. & Tyssens, J., Tweehonderd jaar onderwijs en de zorg van de Staat, Jaarboek voor de geschiedenis van opvoeding en onderwijs 2002. Asse: Van Gorcum. p. 185-203.

Briffaerts, J. (2003). Etude comparative de manuels scolaires au Congo Belge: Cas des Pères Dominicains et des Missionnaires du Sacré Coeur. In Depaepe, M., Briffaerts, J., Kita Kyankenge Masandi, P. & Vinck, H., Manuels et chansons scolaires au Congo Belge. Leuven: Presses Universitaires. p. 167-196.

Briffaerts, J. (2002). What was it like in the colonial classroom? Ongoing research on the reality of colonial education in the Mbandaka region, Belgian Congo, 1908-1960. Paper presented during the annual conference of the American History of Education Society, Pittsburgh, PA, November 2002.

Briffaerts, J. (2002). ‘De last van het verleden’. Een bevoorrecht getuige aan het woord over onderwijs in Kongo. In Basis / Christene School, CIX, 14 September 2002, p. 27-30.

Briffaerts, J. (1999). De schoolstrijd in Belgisch Congo (1930-1958). In Witte, E., Degroof, J. en Tyssens, J. (eds.), Het schoolpact van 1958. Ontstaan, grondlijnen en toepassing van een Belgisch compromis – Le pacte scolaire de 1958. Origines, principes et application d’un compromis belge, Brussel: VUB PRESS. p. 331-358.

Briffaerts, J. (1995). Over Belgische politiek en Congolese scholen. Unpublished seminar paper. Vrije Unversiteit Brussel.

Briffaerts, J. & Dhondt, P. (2003). The Dangers of Urban Development. Missionary discourse on education and urban growth in the Belgian Congo (1920-1960). In Neue Zeitschrift für Missionswissenschaft, LIX, 2, p. 81-102.

Briffaerts, J. & Vancaeyseele, L. (2004). Le discours de la nouvelle éducation dans le contexte colonial: le grand malentendu. Paper presented at the 26th International Standing Conference for the History of Education in Geneva, July 2004.

Budd, R.W., Thorp, R.K. & Donohew, L. (1967). Content analysis of communications, New York: MacMillan.

C

Catteeuw, K. (2001). Als de muren konden spreken, schoolwandplaten als visuele media in het Belgisch onderwijs. text doctoral seminar K.U.Leuven, March 2001.

Ceuppens, B. (2003). Congo made in Flanders? Koloniale Vlaamse visies op “blank” en “zwart” in Belgisch Congo. Gent: Academia Press.

Ceuppens, B. (2003). Onze Congo? Congolezen over de kolonisatie. Leuven: Davidsfonds.

Claessens, A. (1980). Les conflits, dans l’Equateur, entre les Trappistes et la Société Anonyme Belge (1908-1914). In Revue Africaine de Théologie, 4, p. 5-18.

Claessens, A. (1980). Les péripéties de la vie contemplative des Pères Trappistes à Bamanya (1894-1909). In Annales Aequatoria, I, p. 87-115.

Cleys, B. (2002). Andries Dequae. De zelfgenoegzaamheid van een koloniaal bestuur (1950-1954). Unpublished master’s thesis. K.U.Leuven. (This thesis was actually published at the website http://users.skynet.be/st.lodewijk/e-thesis/index.html. ).

Collins, R. et al (1994). Historical Problems of Imperial Africa. Princeton: Markus Wiener.

Cooper, F. (1994). Conflict and connection: rethinking colonial African history. In American Historical Review, V, p. 1516-1545.

Coquery-Vidrovitch, C. (1993). Histoire des villes d’Afrique noire. Des origines à la colonisation. Paris: Albin Michel.

Corbey, R. (1989). Wildheid en beschaving. De Europese verbeelding van Afrika. Baarn: Ambo.

Cornevin, R. (1989). Histoire du Zaire: des origines à nos jours. 4e édition. Paris: Payot.

Couttenier, M. (2004). Fysieke antropologie, koloniale etnografie en het museum van Tervuren. Een geschiedenis van de Belgische antropologie (1882-1925). Unpublished master’s thesis. K.U.Leuven.

Couttenier, M. (2002). Antropologie en het museum. Tervuren en het ontwerp van ‘zelf’ en ‘andere’ in een Belgische burgerlijke ideologie (1882-1925). Text from doctoral seminar, January 2001.

Crocco, M. & Waite, C. (2003). Fighting Injustice through Higher Education. Paper presented at the British History of Education Society Annual Conference, December 2003.

Cuban, L. (1993). How Teachers Taught. Constancy and Change in American Classroom, 1880-1980. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

D

Dams, K., Depaepe, M. & Simon, F. (2002).