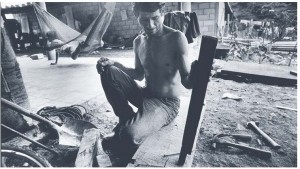

Unfinished Structure – Photo by author

Violence is everywhere (Lindiwe, Hector Peterson Residence).

In order to understand the concept ‘awareness’, Hastrup’s (1995) explanation of consciousness is invaluable, especially to identify with people’s behaviour in violent situations. She explains that our patterns of thinking are not subject to paths of practical reason, but that we rather constantly reformulate our whole existence through our actions; a reconsideration of our ideas of consciousness is thus necessitated (ibid.: 99). Hastrup reminds us that we are inarticulate and that expression is not limited to the verbal. Expression, rather, takes place in various forms (ibid.).

Given Hastrup’s suggestion to understand consciousness from multiple angles, we approach a field within which questions of ontology and methodology join: how do people think and how do we know? (ibid.; Ross 2004: 35). What tools should anthropologists use to access these forms of consciousness that are so intertwined in social space, affecting it, being affected by it and being its defining capacity? In an environment of violence, students are affected, they can potentially have an influence on this through the tactics they use to stay safe and, at the same time, can become the defining capacity of such an environment. These are among the dynamics involved in conceptualising ‘awareness’ of potential danger in potentially dangerous areas. This awareness is positioned on various levels.

We cannot fully comprehend other people, except through structured imagining or ‘intuition’, perhaps deducing part of their implicit reasoning from its (‘intuition’s’) various expressions. Knowledge is not directly and exclusively expressed in words. Situating knowledge in experience rather than in words and, consequently, in the recentred self rather than in the floating mind, changes the location of knowledge. It is largely unexpressed and reserved in the habit-memory, and not exclusively in the brain. Even when they are conscious of the environment of which they are part, this involves a degree of inarticulacy on the part of human agents (Hastrup 1995: 99-100). I argue that knowledge of a violent environment (informed by experience, stories or witnessing) becomes inscribed in students’ bodies through habituation; the tactics used to stay safe are thus relocated in expressed, and (very importantly), unexpressed consciousness. Therefore, bodily experiences (in addition to the exchanging of stories, investing in a technology of safety, and exchanging gossip in social networks) of being in the world inform our knowledge of violence and the way we distinguish between the safe and unsafe (Lindegaard and Henriksen 2004: 46). It is in this light that the concept ‘awareness’ is employed throughout this chapter.

Space, violence and resistance

Former notions of space regarded it as merely an area which is permeable, neutral and accessible to all. But more recently ideas of space suggest that it is never neutral, and even, as the history of South Africa’s spatial planning proves, that spatiality is overwhelmingly ideological (Ross 2004: 35). According to Michel De Certeau (1988, cited in Ross 2004: 35), to understand a place is intimately related to one’s own position in it. This suggests that the views of onlookers or passers-by will differ from those of people who more permanently occupy the space ‘looked onto’. Ross thus argues that employing spatiality entails an engagement with the emotion and the sensual in everyday life, which would otherwise be ‘alien’ (see also Clifford 1998: 35). Moreover, these spaces are also very fluid and experiences of them differ from person to person. What can be a space of opportunity for a robber is a space of threat and potential loss for another person. While some use the space for calculating escape in situations of robbery, others use it to confront and retaliate. Furthermore, gender and age do not necessarily occupy space in the same ways – movements are moulded by (unwritten) social rules dictated by violence and fear. Space also mutates with time. The scene of laughter can be a scene of murder the next moment, and the same spaces are experienced differently by different people who occupy them. ‘The encoded body and killing zone bec[o]me sites of a transaction where residual historical and political codes and terror and alterity [a]re fused, thus transforming these sites into repositories of a social imaginary’ (Feldman 1991: 64). Spaces of violence may also expand, given the involvement of witnesses or people who come to the assistance of somebody who is being violated.

This brings me to how the concept ‘tactics’ will be employed in this section. There is a number of ways in which the ‘powerless’ employ tactics in negotiating ideologies (notions of who should stay away from certain spaces and when) of proper living. With respect to the definition of ‘tactics’, De Certeau explains:

A tactic is a calculated action, determined by the absence of a proper locus. No delimitation of an exteriority, then provides it with the condition necessary for autonomy. The space of a tactic is the space of the other. Thus it must play on and with a terrain imposed on it and organized by the law of a foreign power … (1984: 36-7).

Later on, he elaborates that:

Tactics are procedures that gain validity in relation to the pertinence they lend to time -to the circumstances which the precise instant of an intervention transforms into a favorable situation, to the rapidity of the movements that change the organization of a space, to the relations among successive moments in an action, to the possible intersections of durations and heterogeneous rhythms, etc. (1984: 38).

Ideology, he argues, is a product of power, a strategic practice, which is used by the weak. The weak or the marginalised resist ideology through tactics and reproduce it to new ends, although for moments at a time. Although they resist, they do not change the broader structural order. As a result of restrictions imposed by for example race, class and gender, they must manage within an ideological space and within broader structures of power. This is achieved through everyday practices of appropriation and consumption, with which people create room to move. These practices take place in a realm divided into two fractions: one where strategy and production occur (powerful/apartheid/segregation) and one where consumption and tactics (weak/segregated/victims/survivors) occur, as a result of which the differentiations within the group of the weak – or the strong, for that matter – become indistinguishable. For instance, in the vicinity of the University of the Western Cape elements of violence (e.g. robbers or murderers) use tactics in relation to the broader structural order – state institutions – and engage in strategic practices toward other people (student victims of violence). The ideology is the existing segregated townships known as the Cape Flats inherited from the apartheid regime which forms part of the broader structural order. Hunted and troubled by intense state interventions, the elements survive through the strategic domination of territory (the vicinity of campus) (Jensen 2001: 32).

Strategies, on the other hand, are the ‘forces’ (structural violence, e.g. racial segregation that caused poverty and crime) that place the people on the Cape Flats in positions where they need to protect themselves (Jensen 2001: 31). Tactics are thus used to resist the strategies (structural order), which is expressed in the forms of violence students are exposed to in the vicinity of UWC.

Lindegaard and Henriksen (2005: 44), on the other hand, use the word ‘strategy’ instead of ‘tactic’, and use it similar to the way Bourdieu (1990) does. According to them, strategies are acts of awareness which are rarely deliberate and reflected upon. Although the term is potentially confusing given its strong connotations to rational choice theory, it refers to social agents’ continuous construction in and through practice (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992: 129). On the one hand strategies of safety are rational since they make perfect sense to the agent, yet on the other hand, these acts are not necessarily expressed or well-planned. I use the word tactic instead, especially to emphasise structures surrounding the university that students resist. In addition, although these tactics are used daily, they do not necessarily change the general social order (poverty, unemployment, crime and so forth). It is here where the significant distinction lies that I make.

Experiences of violence

The violence experienced by students who stay in Hector Peterson Residence and Belhar mostly takes place en route to campus. Students from Hector Peterson Residence are more prone to experiencing violence than those who stay on campus because they move around in places that are considered dangerous, especially the route to campus. At Symphony Way and between the hostel and campus, students have been robbed and stories of rape and attempted rape are told about this area. Furthermore, taxis in the vicinity of Belhar pose additional safety hazards by being the sites of robberies and by being linked to drivers known to be reckless. Students tell stories about their experiences and this serves as a warning to others.

When I took a taxi from the hostel to Delft one Sunday afternoon, I got a great shock when a man sitting in front of me pulled out a gun and demanded money from the taxi guard at gunpoint. Other people in the taxi looked at the man and he asked them what they were looking at, probably to avoid them looking at his face. The money the man received from t he guard was probably enough because he did not harass the other passengers. The driver sped off after the incident and then stopped to tell another taxi driver along the way what happened, in Afrikaans. I cannot really understand Afrikaans, but gathered from their conversation that they wanted to get hold of the man (Peter, Hector Peterson Residence).

Whether they stay in Hector Peterson Residence or in on-campus residences students generally may experience violence in taxis since all residents need to travel to Bellville or other surrounding areas for shopping, religious reasons, research or extra-mural activities. Lindiwe also found herself in a situation which could have led to gun violence:

Violence is everywhere and just the other day when I took a taxi from Bellville, the guard instructed somebody to sit in a specific seat in the taxi. An argument ensued and the guy next to me pulled out a huge gun. I demanded to get out of the taxi, but the guard asked what happened. I told him to open the door first and then ask questions. I got out as fast as possible. The guy with the knife ran away but his friend sat in the front of that taxi. Because the guard got hold of the friend, he was beaten up (Lindiwe, Hector Peterson Residence).

Viewing violence as omnipresent is a way of staying safe because it reminds students to be on guard all the time as it might happen at any time and in any place. If they are not constantly aware of their environment they can become unsafe. Thus students continuously draw on tactics of safety to keep out of harm’s way.

The question of safety when in a crowd

The safety perceived to ensue from being in a crowd, for instance in a confined public space like a taxi, was shaken in the examples of Peter and Lindiwe. When a number of people are together in a small confined space, they tend to feel safe. The presence of others sets aside danger and sociability works to ease fear (Ross 2004: 39) – until a gun is pulled out. Yet the supposed safety found in a group can be largely imagined. The safety felt when in a crowd of people is based on the assumption that others will come to one’s assistance when needed. Accordingly, when people are alone they feel more powerless against potential violence (Lindegaard and Henriksen 2004: 55). Yet in this study it was evident that students often do not come to the assistance of others who they perceive to be under threat. This is mostly because they are afraid that by intervening they might become violated themselves. This is especially the case with female students who see it as risky to get involved since intervening may be to their own detriment.

I heard a desperate cry coming from my neighbour’s room in HPR early one evening. I was unsure from which room the cry came so I stepped out into the corridor to see if I could spot the room. Standing in the corridor I was uncertain whether I should intervene out of fear for the perpetrator turning on me. Instead I decided to retreat to my room and fortunately the security staff came and I later heard that it was a guy beating his girlfriend in her room. What led to my uncertainty to intervene is the xenophobia I often experience in taxis. When people are treated badly by the drivers or taxi guards, I noticed that other passengers simply ignore it. This gives me the feeling that if I should intervene to help a victim and the perpetrator turns on me, other people will not support me (Synthia, Hector Peterson Residence).

Awareness of the possible consequences of intervention therefore holds Synthia back and keeps her safe. She does, however, feel torn between not helping and intervening and in a different setting (Malawi) she would be more willing to intervene. Testing the level of safety in situations is therefore necessary, although students may be more willing to take risks when a significant other is in danger. Mary also fears that when she is in trouble people around will not help her.

I fear that when someone rapes me nobody will intervene while it happens. In Nigeria this will not happen, because other men will run after the offender and beat him up (Mary, Eduardo Dos Santos Residence).

A sense of camaraderie in Nigeria therefore contributes to a feeling of safety for Mary, as well as the fact that she knows justice will be served because offenders will pay for the consequences of their actions. Men act as protectors and the bearers of justice. Because she fears that bystanders in Cape Town will not help her should something bad happen to her, she always walks with fellow students when she goes to her department on campus at night, again confirming that the mere presence of people, especially people who are not complete strangers, is a tactic of safety.

Phumzile experienced an incident where her bag was snatched from her in a public space. Bystanders did not intervene. The bag-snatching took place in Symphony Way where taxis drop off passengers or pick them up.

I saw two guys sitting on the opposite side of the road and it looked to me as if they were waiting for a taxi. When I stepped out of the taxi I saw the two guys move toward me, but I thought they were crossing the road because they were walking to Extension. But then they came toward me, one guy with his hand under his top as if hiding a knife or a gun (I did not see him with anything while he sat waiting) and walked to me as I walked backwards but he then got hold of my bag. I shouted and one guy ran away, but I held onto my bag the other guy held and there was a struggle. At one point the bag was on his side and I held onto the straps. He managed to get hold of the bag and ran off. I followed the guy and ran closely behind him. The guy couldn’t even run. My adrenalin was pumping and I was determined to get my bag, but the guy managed to escape. I told a traffic officer who came by that I had been robbed, but he just went off on his own after I thought that he would help me see if I could get hold of some of my belongings. People passed by asking what happened, but nobody would come up with a solution. My cellphone, cards, ID were in the handbag and it meant that I had to start afresh (Phumzile, Hector Peterson Residence).

Belhar is a predominantly coloured area and racism is often rife in such communities especially towards blacks (see Adams 2005: 9; Du Preez 2005: 14). It is possible that the traffic officer and bystanders did not help Phumzile because she was a black woman. Studies show that whites in America are more likely to help whites in emergencies than blacks (Bryan and Test 1967; Gaertner 1971; 1973; Piljavin, Rodin and Piljavin 1969; Levine et al. 2002). This is not conclusive in the decision not to intervene, however, since other factors may play a role as well. Bystanders may also decide against helping victims depending on the costs involved (Gaertner 1975: 95). On the other hand, Levine (1999: 12) explains that bystanders also interpret incidents a certain way and that the incident needs to be contextualised. People’s accounts of their interpretations of incidents shed light on their decision not to intervene. Not helping a victim, especially when a weapon or threat to be physically harmed oneself is involved, can also be a way to stay safe.

While making a telephone call in Parow one Saturday morning, a guy held a friend of mine at gunpoint. She called me to draw my attention, and thinking she was teasing and not turning back immediately, I turned around eventually to see what was happening. The guy holding the gun was very nervous because his fingers were trembling on the trigger. I thought that I could easily fight the guy, only if the lady were not there. I simply handed my cellphone over. Other people walked by without offering any support and Saturday mornings are very busy around shopping malls. If I were alone I would have held the guy’s hand up to empty his cartridge, and then would have beaten the guy up (Collin, Hector Peterson Residence).

At the same time the response by a group of people against someone who offers violence can equally help everyone to keep safe, as is mentioned by Bulelwa. She said that in Johannesburg, where she comes from, people stand together against violence.

Everybody has this idea that Jo’burg is rough but people can talk on their phones when walking in the streets. Even in the townships. Hillbrow and Yeoville are rough where the Nigerians are though. At the taxi rank near home the taxi drivers will beat someone up if they steal a cellphone. Here people can get away with it and the others will do nothing. So back home there is more unity (Bulelwa, Coline Williams Residence).

In Nigeria, according to Collin and Mary, and in Johannesburg, according to Bulelwa, bystanders would fight the perpetrator. According to Chekroun and Brauer (2002), people are more likely to exercise ‘social control’ in high-personal-implication situations. They define social control as ‘any verbal or nonverbal communication by which individuals show to another person that they disapprove of his or her deviant (counternormative) behaviour’ (Chekroun and Brauer 2002: 854). Put differently: if people feel a personal threat in situations where they see someone else being held at gunpoint, they are more likely to intervene, and thus contribute to restoring order in a sense.

Latané and Darley (1970) cite instances where victims of murder and other offences were left unattended even after the assailant had already left. In one instance a switchboard operator who was raped and beaten in her office in the Bronx ran outside the building naked. Forty people surrounded her and watched how the assailant tried to drag her back into the office and none of them interfered. Two policemen happened to pass by the incident and arrested the assailant (Latané and Darley 1970: 2). The authors conclude that if bystanders fail to notice, interpret and decide that they have personal responsibility toward the victim, they are less likely to intervene. In addition, the presence of other people is more likely to keep a bystander from rescuing a victim. These explanations help understand the possible thinking processes involved in people’s decisions to intervene when seeing something bad happen to somebody.

When drastic situations call for extreme tactics

Using the train to commute around Cape Town is known to be risky and many commuters have experienced violence of one or other form (Marud 2002), leading to protests against the absence of security on trains. A number of participants in this study also told of frightening experiences they had on trains. Other stories tell about people who were robbed in trains, especially trains that run along Cape Flats lines. Such stories are part of the symbolic order students create to stay safe. Because of such stories students avoid commuting by train. Here follow stories told by two students who survived after they had no choice but to jump from the train.

At every station stop I raised my head from the book I was reading to check who get on and off and at one stop 4 guys boarded the train. Although I found it strange that they were standing since there were vacant seats, I resumed reading. A commotion and people scurrying drew my attention to those 4 guys. I had heard about gangsters who rob people, but it was clear that these guys were not interested in people’s belongings, so they must have been out to kill. It was very surreal, and even seeing one of the guys stabbing an old man repeatedly with a knife, seemed like a dream to me. Women ran around in the carriage and it dawned on me that I needed to do something fast. The window behind me was fortunately broken and I told myself that I needed to jump because the guys were coming my way. I told myself this continuously to convince myself and looked out the window to scan the railway track in search for poles. I previously heard that when people jump from trains, the poles along the tracks are what kill them. Fortunately there were no poles. I knew that the same knife that killed the old man was what would kill me. The train fast gained momentum and as it did so, I moved out of the train through the window frame, held on the outside and jumped. Fortunately there was no oncoming train otherwise I would have been killed. I moved as I fell so as not to do too much damage to one part of my body especially, my head, but could not avoid bashing my forehead. I lost consciousness from the fall. Security guards patrolling the tracks found me and they took me to the next station. Later I learned that people in that train were thrown off by those guys (Peter, Hector Peterson Residence).

Because Peter had to use the train to commute, he had his own safety tactic while he was doing so – he looked at the doors at every stop, making a ‘mental’ note of potentially threatening people who boarded. This tactic was informed by stories he heard about what happened to other commuters who were robbed in trains and he used it to stay safe. His tactic was also based on a tacit embodied response to what made him feel uncomfortable or raised a feeling of potential threat in him. His first clue was that the four men remained standing although there were seats available. When he saw the men stab someone his response was almost wholly embodied, initially making it seem like a bad dream. When he realised that jumping out of the train might be all that could save him, he drew on other peoples’ stories, informing him that, 1) he could jump and might survive, and, 2) that hitting a pole might kill him. Before jumping he scanned the railway tracks for poles. Grabbing onto the window frame and hanging outside for a moment was apparently almost instinctual, as was the realisation that he should try to fall in a way that would not damage his head. As Lindegaard and Henriksen (2005) argue, the body is socially informed – one perceives and experiences the world in an embodied way, while at the same time also ‘learning’ how to behave and respond in bodily ways, albeit often without thinking about it consciously (cf. Csordas 1994; Bourdieu 1990).

Phillip also had a horrible experience on the train. He traveled first class on the train – another tactic of safety since the tickets are more expensive, and therefore a ‘better class’ of people will supposedly travel first class. According to Philip:

The train was full of passengers and I was in a first class carriage. Then at Belhar Station most of the people got off and there were only three remaining, me and two other passengers. At that point I was busy reading a letter my brother sent from home and was not paying much attention to my surroundings, but four guys stepped onto the train when it stopped. The next thing I saw was those guys pulling out knives and they started stabbing people. People rushed to each other so that they could be together and my hand was stabbed because I tried to stop one guy. Then the guys started throwing us off the train through the windows. One man died instantly as his head hit the ground, but I and two others survived. This happened below the bridge at Spa and men were playing cricket close by. I could not get up after the fall and told the guys about what happened without realizing that I was bleeding. Metro Rail Security then came and called the ambulance who took me to Delft clinic, while the others went to Groote Schuur Hospital. Staff at the clinic was not very helpful and did not even x-ray me. They just stitched me up. I did not even bother taking it up with them because it would not help, so I just returned there to have the stitches removed (Phillip, Hector Peterson Residence).

In extreme situations such as the one in which Peter found himself, people in the area of Belhar and students at UWC particularly, are forced to think fast to save their lives. After Peter’s traumatic experience, he never used the train again. Since Collin (see his story further in this chapter) and other students learned of Peter’s experience, they never take the train anymore. I also hardly use the train unless someone accompanies me. The few occasions on which I actually used the train, I felt very uncomfortable. As I sat in a deserted carriage in front of broken windows it conjured up stories I had heard about robberies and of outsiders throwing bricks at passengers through broken windows. Yet, for some students the train is the only reliable form of transport and they are comfortable using it. Bulelwa, who comes from Gauteng said:

Commuting by train feels very normal. Even wearing my chain and bracelet is fine. I even use my cellphone in the train. At the moment the train is my only means of transport. The train is also cheaper although it is not very reliable because one can be late for an appointment (Bulelwa, Coline Williams Residence).

My own gendered expectation was that Bulelwa, rather than Collin, would be particularly careful of the train. Besides being aware of the possibility that something might happen to her on the train, Bulelwa also behaves with confidence. For her Gauteng is more violent than Cape Town and she feels and behaves as if she is ‘tough’. This is very similar to how I generally behave when walking in the vicinity of the university. Lindegaard and Henriksen give similar examples, but of men who adopt ‘feminine’ strategies of safety, that is, they move together in groups or run fast to cover potentially threatening spaces. Bulelwa and I use more ‘masculine’ tactics and at the same time we also obtain a sense of safety through the idea that bad things only happen to ‘other’ people. By behaving in this way, consciously or unconsciously, we both create a space in which we feel safe, but it may also make us more vulnerable.

The following section looks at the influence gender roles have on the way people create safety for themselves. Information gathered at a workshop at the university helped explore how students relate to each other in terms of gender.

Gender roles

Attending a workshop run by the HIV/AIDS Unit of the University of the Western Cape, it was very interesting to learn what perspectives peer facilitators of workshops hold about what it means to be a man and a woman respectively, especially concerning HIV/AIDS. More interestingly, the men attending the workshop were part of MAP (Men As Partners), and were being trained to facilitate HIV/AIDS workshops on campus. At one point during the workshop men and women formed separate groups and listed things about their gender they were proud of. The women struggled for a long time to think of things they could be proud of, as opposed to the men, and only after a long time managed to list some. Taking a look at the discourses around gender is important when studying violence, since they impact on how women and men view themselves, and each other, in relation to violence. Although their lists might not have been the same had the context been different, or perhaps did not reflect what they would have stated individually, this was what each group listed:

What it means to be a woman

They are able to express emotions without being ashamed of it; give birth; are more sensitive and caring; do not have to pretend that they are strong; can take advantage of men; are happy about affirmative action; make better parents than men; can do anything without being stigmatised, e.g. have a man’s name and not be called a moffie.

What it means to be a man

They were born to lead; can physically dominate; when they speak people listen; have better opportunities and salaries; do not live in fear; can protect; women depend on them.

During this group exercise, women and men took pride in stereotypes pertaining to their respective genders without even realising it. The outcome of this exercise not only mirrors gender roles in broader society, but also the way most of the participants deal with and think about violence. Unlike the men, the women failed to see themselves as initiators, leaders, protectors, speakers, and as being able to physically dominate or protect.

When women and men were asked to say what they could do if they switched gender roles, it was interesting that women failed to see their value as women as opposed to their value if they were men. Men valued themselves both as men and as women. Each group listed what they could do if they were members of the opposite gender:

What women could do if they were men

They would not worry about sagging breasts; could wear the same shirt the whole week; do anything they want to and go anywhere; respect women; break the silence around women abuse; have the physical and financial power to start a war; leave responsibility of children to woman (and just pay the money); have sex with anybody; teach sons not to cry but to ‘be a man’.

What men could do if they were women

They could express their emotions; get their pension at the age of 60; share affection; look after their partner; be open about sex issues to other women; spend more time with the family; be open and honest; get away with lots of things; be loving and caring; break the silence; be conscious about nutrition.

Apart from the fact that women felt they would be freed from sagging breasts if they were men, women also imagined having freedom of movement, sex and action; they identified with being men who respected women, taking the initiative, starting war and fighting against abuse. Fighting against abuse comes across more as a wish in this context and this would likely not have been among the responses in a different situation where MAP was not the focus of the workshop. The men’s responses also formed part of gender-stereotypes about women and the idea of breaking the silence seemed more of a wish, especially given the fact that women themselves did not mention that in the first round of the exercise. Such ‘… discourses inform tactics of safety’ (Lindegaard and Henriksen 2004: 58) and are generally the ideas women have of men in danger and vice versa. If women for instance feel restricted in their movements and actions and feel that they need to stay indoors to stay safe as opposed to what they described men’s experiences are, their perceptions of women and safety inform the way they keep themselves safe.

Although the students in the workshop were aware of changes that have taken place in South Africa with regard to social mobility for women (for example, the significant presence of women in parliament), their responses suggested that dominant gender stereotypes still affect their thinking. Culturally defined beliefs about what it means to be female or male thus still persist (Golombok and Fivush 1994: 18). ‘Males are stereotypically considered to be aggressive or instrumental; they act on the world and they make things happen. Females are stereotypically relational; they are concerned with social interaction and emotions’ (Bakan 1996; Block 1973, cited in Golombok and Fivush 1994: 18).

Education influences how strongly people adhere to dominant discourses (Golombok and Fivush 1994: 19). During the workshop women with university degrees nevertheless agreed on gender stereotypes and regarded male traits more highly than their own. If women value themselves less than men, this will affect the relationship between them (Bammeke 2002: 76) and their attitude towards violence.

Gender and violence

Women and violence

Men and women in this study had different experiences of violence based on gender. Because women are viewed as ‘soft targets’, they are violated through robbery, rape and other forms of violence. For women, living in a potentially violent situation can be difficult, not only because they fear victimization, but also because it is difficult to speak out against it.

Women also should learn to speak about violence, because when they talk, others will hear their stories and will also want to talk. In this way women can then build networks and fight against violence (Liz, Hector Peterson Residence).

Men have power over women partly because of the dominant discourse and expectation that women are weak and vulnerable (Boonzaier and de la Ray 2004). This reinforces the subordination of women who fear being violated.

Being a woman makes one feel vulnerable because one does not have the strength to fight and one does not have a voice to talk. The threat of something happening to me is always real. Not a day passes when I do not feel conscious of security. [Practicals in] Nyanga [Nyanga, meaning ‘the moon’, is one of the oldest black townships in Cape Town. It was established in 1955 as a result of labour migration from the Eastern Cape and was a site of protests against the ‘pass laws’ in apartheid in the 1960s and 1970s. Black-in-black fighting allegedly perpetrated by corrupt police in the early 1980s made Nyanga well-known] is the closest place I could choose [to conduct my research] but it poses quite a danger because of hijackings that take place there. I am conscious walking around there every time and not speaking the language puts me at greater risk. I am told at different times to go home and not take up South Africans’ jobs. The speed at which taxi drivers drive is very careless and as if there is no tomorrow. I just feel unsafe (Synthia, Hector Peterson Residence).

A number of things make Synthia feel insecure as a woman in the midst of possible violence. She is not strong and fears she will not be able to ward off an attacker. Hijackings that take place in the vicinity of her research site are threatening and she fears exposure to this. The language barrier between her and the people in Nyanga, the xenophobia directed at her and the speed at which taxis drive alsomake her feel unsafe. This is even more harrowing since Synthia needs to pass through this space every day. Yet Synthia refuses to stay silent about violence and after the recent attack on her, close to Hector Peterson Residence, she pursued the fact that the residence staff acted very imperturbably in that regard.

Expectations about how women should behave in dangerous places affect their responses in potentially violent situations. Female passivity is viewed as second nature, ‘but it illustrates that emotions as other forms of practice are informed by discourse’ (Lindegaard and Henriksen 2004: 55).

… men usually weigh up the situation and see what they should do, if they should confront the perpetrators. Women can’t weigh up the situation, they should avoid it at all costs and that is what I do (Melanie, Hector Peterson Residence).

Women express a double vulnerability – they fear being mugged but also being raped.

Men have advantage because they think that women are the weaker sex. So women feel scared that they are women because men would not only take away women’s purse, but could also rape them. But things are a bit level now because guys should also be scared that they could get raped. Things are a bit safe now because there are security staff at the hostels and they are trying their best. We also have to think about not walking around late because that makes a person an easy target. This Kenyan guy who was killed during the vac[ation] must have gone to a shebeen. The Barn was closed and they should really think about keeping The Barn open (Lindiwe, Hector Peterson Residence).

The murder of a Kenyan student from Hector Peterson Residence near the hostel triggered awareness of the danger students face outside the hostel. Unlike in the past, the rape of males is increasingly feared.

Women nevertheless feel vulnerable and in need of protection by men; female students who cross the field (see figure 1.1 A-C) to campus get a sense of safety from the presence of security staff who stand watch at an unfinished structure on the field. Since men are viewed as protectors, they stand guard, irrespective of whether they are equipped or even trained to deal with violence. If anything should happen to a student, security is supposed to release the dog to chase the perpetrator off. Yet in one instance where a student was attacked the security staff member held onto the dog – probably as a means of self-protection.

Fig.1.1.A – The field between UWC and Hector Peterson Residence

Often security staff do not stand watch on the field between campus and HPR. Students who cross the field at midnight run the risk of attack because the field is deserted. The unfinished structure seems to be a good place for muggers to hide and catch their ‘prey’ unguarded, which is exactly why security staff are placed there. It is also one of the places both males and females have identified as a dangerous space. It makes them feel very vulnerable and they only feel at ease once they passed it.

Fig.1.1.B – Unfinished structure

Thando feels safe once she gets to campus, and those years when she stayed in the hostel, she felt safe once she passed that unfinished structure. ‘People just hide away behind that structure and appear very unexpectedly. It is that unexpectance that catches people off-guard’ (Thando – used to stay in Hector Peterson Residence).

Fig.1.1.C – Path to Hector Peterson Residence

Staying safe through confrontation or escape

Women who do not respond to situations of violence in the way Phumzile did in the example given earlier, rather run away or simply do nothing. This is often caused by the fact that they have been socialized and are expected to be passive. Women who are socialised into fulfilling traditional roles of ‘submissiveness’ tend to sustain such behaviour because that is how things are supposed to be (Bourdieu 1977). There are usually other significant similarities among women who are abused, such as low income, low level of education and residence in a village (Faramarzi, Esmailzadeh and Mosavi 2005: 5). Studies conducted among wealthier, highly educated women from affluent areas might show different results. Once women are exposed to stories that contest such passive notions, for example, of an abused woman who took her children and left the house, they behave differently. Examining women’s exposure and responses to domestic violence is very helpful in understanding their responses in relation to community violence.

What factors contribute to women either fighting or taking flight in situations of violence? This can be illuminated by comparing two participants in this study.

It was after four in the afternoon and I walked to my previous home which is close to the University’s train station. It was very windy that day. As I walked I saw two guys walking in my direction but they passed me. I continued walking but then something told me to turn around. It was really windy and when I turned one of the guys grabbed at my bag. The guy was caught off guard as he was not expecting me to turn around before he had taken my bag. Immediately, he said that he was only looking for a R5. I replied that I did not have a R5 even though I had money as well as my cell-phone in my bag. The second guy then approached. The first guy insisted that he was only looking for a R5 as if a R5 was of little value to a university student. When I again replied that I did not have any money, the first guy then rudely demanded that I give him my earrings. As I attempted to pull the earrings from my ears, I insisted that I remove them myself. At this time, the second guy seemed extremely irritable as I was still trying to assert myself under the circumstances. He threatened to kick me. The earrings were not such a concern because they were old. After giving them the earrings, the guys noticed my tekkies. I noticed this and subsequently realised that they were not done with me yet. The two guys then walked with me to a nearby park where I could sit down to remove my tekkies. I decided that I would not allow them to take my shoes, and starting to think about possible ways to prevent this. At the park, the two guys sat down on poles situated towards the end of the park. I stood between the two poles (that they were sitting on) at this time, and while they looked down the road in one direction to watch for any oncoming people, I ran in the opposite direction. I ran towards a road where I saw another guy and other people who were building on one of the houses in that road. I knew that if the two guys chose to follow me, they would have to deal with those builders. I managed to get away safely (Jo-Anne, lives slantly opposite Hector Peterson Residence).

Jo-Anne did many things – she looked out for men (who are viewed by women as a potential threat), and, when she passed them, she turned around. Although she lied about the contents of her bag, she gave them her earrings, but tried to maintain control by taking them off herself. As soon as she saw an opportunity she ran away – towards other people. Although in a distressing situation, she planned her escape and waited for an opportunity to do so. Afterwards she became even more careful and hardly ever walked home alone again. She rather waited for her mother to come from work in the evening to pick her up from campus than leave campus earlier. She now also avoids spaces that she thinks will place her in a compromising position. These fears are spread throughout other areas in her life:

I recently obtained my driver’s licence, but even so am very afraid to drive on routes unfamiliar to me. My fear is inadvertently encouraged by my mother’s bad experience with driving. When my mother took my father to work one evening she took the wrong turn on her way back home. She ended up in a very dangerous place and could not even get out of the car to ask for directions in fear that something might happen to the car or to her. Since then my mother sticks to routes she is familiar with and where she can maintain a sense of safety. Due to the fact that my mother displays this behaviour, I fear that something bad might happen to me should I dare to drive on unfamiliar routes (Jo-Anne, slantly opposite Hector Peterson Residence).

This example is one of many that reflects how Jo-Anne’s socialisation in her family impedes the way she faces threatening situations. Because I encouraged her to drive to a mall she had never driven to before, she said she would think about it, but later that night called me to ask if I would accompany her. This was the first time she drove outside of the area where she stays. Although she decided to drive to the Mall, she asked to be accompanied.

Jo Anne had heard stories about potential danger and had been exposed to it. She is aware of tactics to stay safe and actually behaved in a very calculated way when she was confronted by thieves, but she generally responds in a more ‘feminine’ way in terms of safety tactics – she tries to avoid danger by staying in safe spaces or by looking for the company of people she knows and trusts. It must be noted that stories involving danger may also induce fear, but still informs people about what might otherwise not be experienced. In other words, hearing stories of what other people do in situations of danger informs people of what to do in such situations. ‘Naiveté’ could also put people at risk and they may even be blamed for their ‘ignorance’ especially in instances where people believe our actions are ‘unintelligible’ (Richardson and May 1999: 313). Still in other situations where people are inundated with stories involving danger, they may shut off to the stories.

Everyday I walk down that road I am very anxious because of the robbery before and I would rather have my mother pick me up from campus after work and wait an extra hour than walk home. Otherwise my brother would wait in front of the house and watch that I walk safely. But that road to campus is very dangerous because it is isolated and surrounded by bushes. Subsequently, you cannot see when someone is hiding behind these bushes. Even though there are security guards, one hardly sees them as they tend to focus more on the students walking towards the Belhar residence. I feel safer on campus because there are other people around. Walking down that road with anxiety may be a bad thing because the robbers will sense the fear and will prey on that, is what my brother told me. If one walks boldly they will wonder why the person is so bold and assume that the person is carrying a weapon. And when my mother informs me that she will not be able to pick me up from campus I worry about getting home that whole day and have butterflies in my stomach. If I were a man I would have felt confident in my ability to protect myself. Men usually have some or other experience with violence either on school or elsewhere which enables them to protect themselves. Women on the other hand, usually do not get into fights and I am one who stays in the house most of the time and therefore do not feel confident in protecting myself (Jo-Anne, lives slantly opposite Hector Peterson Residence).

Women like Jo-Anne mostly follow passive tactics, especially when dominant figures in their lives like mothers or brothers reinforce their understanding of themselves as potentially ‘acted-upon’ females. According to Lindegaard and Henriksen (2005) staying inside the home is a female tactic of safety, and is often explained as being a result of women’s weaker physique and lack of ability to defend themselves. Greater culpability is attributed to women, partly because of the assumption that they run a higher risk of being confronted with violence. Women are expected to stay inside the home because being in the ‘wrong’ place at the ‘wrong’ time makes women vulnerable to violence (Richardson and May 1999: 313). This tactic reinforces gendered behaviour – Jo-Anne does not move around by herself because she feels vulnerable, while this tactic also confirms that she is a female. What is also evident in Jo-Anne’s story is that she would value being a man because she would have more confidence then – similar to the women’s responses in the workshop discussed previously. Such notions aid passivity and perpetuate the idea of women being the weaker sex. Lindiwe, however, because of her exposure to stories that counter notions of women as passive and complacent, responds differently to the threat of violence.

Someone in Bellville asked me if I had a cellphone and someone else wanted it, what I would do. I said that I would tell him to buy his own. He then asked me what I would do if the guy had a gun and wanted my cellphone. I said that I would let it fall to the ground so that neither of us could have one. The guy told me I’m crazy. It is not as if I am not afraid of violence, but I feared it for a long time. When people tell me that they have been robbed, I tell them to be glad their life was not taken away from them. Some people would count their possessions more valuable than their lives (Lindiwe, Hector Peterson Residence).

Lindiwe had been exposed to potential violence in her home for many years. She eventually decided that she had lived in fear for too long and needed to have a sense of control in her environment. Lindiwe had a friend who defended herself in a near-rape situation. Being surrounded by people who confront threats, I suggest can empower women to do the same. Daring the attacker was used by Lindiwe’s friend to reduce the power the attacker had over her as a potential victim, thus confronting potential danger, and can be a tactic to stay safe.

If someone should try to rape me I would tell him to go ahead and rape me. My friend did this and they [the assailants] wondered why she said so, and walked off thinking that maybe she had HIV and would pass it on to them (Lindiwe, Hector Peterson Residence).

In Lindegaard and Henriksen’s (2005) scheme of possible tactics to stay safe, this would be a more masculine strategy (seen in the example of Colin at the train station, discussed further below), although used by a woman.

Men and violence

As noted earlier, men feel responsible for women in unsafe areas, take on roles of protectors and will more often than not fight in situations of danger. Yet women are supposed to be protected from men. The following incident illustrates how men respond in ways similar to the tactic used by Lindiwe’s friend, thereby reducing the power they feel potential attackers might exert over them.

Women on the other hand will not necessarily fight but will try a different tactic to avoid dangerous situations by either waiting for another person to walk with, or by turning back. In addition, women might also say something to their potential attacker to keep him from attacking, like screaming or speaking aggressively to hold on to their possessions, as in Phumzile’s case.

As I neared Unibell Station I saw a guy rushing across the bridge to say something to another guy on the other side of the station, while looking in my direction. I then walked to one guy of really big build and stood in front of him chest-to-chest looking him four-square in the eyes. The guy then greeted me. I told the guy: ‘You’re crazy’, and walked away (Collin, Hector Peterson Residence).

What happened in Collin’s instance was that he could see the two men on both sides of the station planning something against him. It was December vacation and the area around the station was deserted. The two men obviously communicated with each other and the big man smiled at the other as he crossed the bridge towards Collin. This was Collin’s clue. He faced the bigger man and because of his boldness the two men were caught off-guard. One of the stories that circulated among students and people who have experienced violence, is that robbers detect their potential victim’s fear and capitalise on that – this was also what Jo-Anne’s brother told her. Behaving boldly is accordingly seen as a good defence mechanism.

Fig. 1.2 Unibell Station Unibell Station, which is the train station between UWC and Belhar. This was where Collin confronted one of the men he suspected was conspiring to rob him – Photo by author

Collin comes from Nigeria and from a university where violent student uprisings are rife, and the cause of many fatalities (Bammeke 2000). He had been in the army and was trained to sense and act on any suspicious behaviour of people who pose threats. Being socialised and trained to be aware of his environment thus help him to keep safe, while it also masculinises him (Lindegaard and Henriksen 2005: 49).

According to one of my participants, women become distraught in situations of danger and therefore are easy targets. ‘… women tend to be overtaken by their emotions more than men. Therefore, men would be able to separate themselves from the situation and will act swiftly’ (Graham, Hector Peterson Residence). Without neglecting to mention that masculinities are fluid over time and in different places (Barker and Ricardo 2005), men tend to grow up in environments where they need to be able to defend themselves. Boys tend to play roughly in school grounds and are expected to pick fights with other boys as part of learning to be a man. Exactly because of these discourses about what it means to be a man, police tend to laugh at men when they report sexual assault. The views men have of women have implications for gender-based violence (Barker and Ricardo 2005: 19).

Like men, some women also behave in a confrontational manner or will resist when threatened. When two men tried to grab Phumzile’s bag from her, she screamed and held to it tightly. One of the men ran off while she continued to fight to keep her bag from the other. He managed to thrust the bag under his armpit while she held onto the sling, but eventually he tore it out of her grip.

Man or moffie?: Hierarchical masculinities

As discussed earlier, men are often seen as protectors against, or initiators of violence. Moffie is a derogatory term referring to gay men, but is also a term used to refer to males who display ‘feminine’ traits by talking in a feminine voice, or moving in ‘feminine’ ways, or who, in relation to danger, would run away instead of fight. A moffie would not be able to defend himself when in a confrontational situation with another man. When a man is referred to as a moffie this is very insulting because it constructs him as a lesser man. This might happen, for example, when mothers pamper boys too much – they are told that the boy will grow up to be a moffie. Such boys are teased at school. Khaya would be referred to as a moffie among coloured men, or isyoyo among Xhosa-speakers. His safety tactic is not necessarily to stay inside or to avoid unsafe spaces, but to run away when he senses or sees a threat.

At one big fight in front of Chris Hani Residence I was told that I am a betrayer, but I went to call for help while they fought. Fighting is something I avoid at all costs. I am short-tempered and would just throw something at a person (Khaya, Eduardo Dos Santos Residence).

Tactics to stay safe (in this case running away from danger and calling for help) communicates what kind of man Khaya is. Challenging the ‘feminine’ or ‘masculine’ tactics for safety therefore makes a person less of a woman or man in the eyes of others (Lindegaard and Henriksen 2004: vi). Gender discourses inform tactics of safety. Men are socialised to respond to threats of violence with anger; no signs of vulnerability must be seen when men are on their own, walk to campus, to Symphony Way and so forth. Men are protectors and potentially violent; when they speak people listen. Men deal with violence either in protective or aggressive ways (ibid.: 58). In the words of Simpiwe, ‘violence makes me feel very responsible to people who are vulnerable in such (violent) situations’, the ‘people’ being women and children. However, as we have seen in this chapter, these engendered tactics for safety are sometimes contested, as when a woman resists robbers, outwits them and calculates a safe escape.

In contexts of South African prisons and labour compounds where masculinity is renegotiated, the ‘weaker’ male inmates are claimed as ‘wives’ of the stronger male prisoners. The dominance of the stronger man is sustained through fear evoked by violence (Niehaus 2000: 81; Lindegaard and Henriksen 2004: 61). These roles as ‘husbands’ exaggerate men’s masculinity enabling them to be ‘real’ men (Niehaus 2000: 85). Masculinity is not the only factor to consider in understanding how men deal with perceived threats.

Issues of connectedness and race further compound spatiality. The space around the university campus is different from the spaces occupied by the adolescents in Lindegaard and Henriksen’s research. Since students staying in residences may not originally be from Cape Town or South Africa even, there is no sense of belonging to the area, particularly among men. There is no attachment to a place as there would be when one lives there. These students like Simpiwe come from other parts of the world, and when they walk into ‘danger zones’ Belhar or Bellville, they ‘know’ they ‘should not be there’ in the first place.

Bellville is kind of scary, especially the coloureds. I have nothing against coloureds but there are strange characters around there. There is just a feeling that tells me that I have to be alert. If I need directions, I would rather find the place on my own. The taxi rank area is especially unsafe (Simpiwe, Cassinga Residence).

At the same time Simpiwe’s statement seems to hint at a homogenisation of coloureds. Jensen (2001: 4) explains that the homogenisation of coloured men is so forceful that each and every coloured man on the Cape Flats is under persistent suspicion of being a gangster. Even men coming from townships (both coloured and black) in Cape Town are ‘aware’ of the racial boundaries between coloured and black townships. This means that blame is not only directed at gender when treading in ‘wrong’ places, but at people of ‘other’ races, too. In addition blacks cross these racialised boundaries more often than the other races to go shopping, or to university – basically due to economic inequities.

Storytelling

Knowing the power of a story heard is that the story occurs within the listener (Simms 2001).

As indicated earlier, people’s experiences of violence are informed by the exchange of stories about violence. Storytelling informs tactics of safety and makes people aware instead of conscious of violence. Tactics are in other words people’s means to avoid, escape or confront danger, which they do not necessarily consciously reflect on (Lindegaard and Henriksen 2004: 46). Storytelling also creates a feeling of solidarity among group members and may not necessarily be based on actual events that occurred in a specific place. It might have the purpose of reinforcing feelings of mutuality – a group feeling. Stories of danger may also be based on what might possibly happen to a person. Such feelings are then associated with preconceived ideas of a violent situation someone else was in, and, based on these feelings, we employ tactics to keep safe. We do not know if walking in a ‘dangerous place’ at a specific moment will result in our belongings being snatched from us or in being held at gunpoint. But it is stories that inform us not to walk in certain places at certain times of the day – when such places are deserted, when we have valuable things with us, or when we are alone. This does not, however, make danger less real or less likely to happen.

When foreigners come to South Africa they are unable to distinguish between the safe and unsafe because they are not informed through stories or by witnessing people being held at gunpoint, for example, apart from the stories they may have read in the news media. They are not a part of the formation of a symbolic order. This might make foreigners easier targets. In addition, foreigners are perceived as having money on them and are therefore targeted for robbery.

Recognising ‘shady characters’ – Tactics for staying safe

One should also always listen to one’s instincts as Oprah Winfrey says, because in those situations they are women’s best bet! (Melanie, Hector Peterson Residence).

As argued previously, storytelling, in person or via the mass media, about violence informs our tactics of safety. These stories could also inform foreign and/or first-year campus residents to distinguish between the safe and unsafe, and also help them to recognise ‘signs’ of people and places that are potentially unsafe. Although I discussed this awareness briefly through Collin’s experience at the train station, this section tries to unravel how participants ‘recognised’ ‘shady’ characters and used tactics to escape dangerous situations. The characteristics described by the participants cannot perfectly determine who is dangerous or not, but nevertheless aid them in creating feelings of safety.

I waited at the bus stop not far from the residence. I saw two guys approaching the bus stop and they looked very suspicious. What makes them look suspicious is the way they walk, their behaviour and especially the way they look at a person – intimidatingly! A woman walking in front of them crossed the road to walk to the garage. A year ago the garage did not exist. Then I planned that if they came too close to me I would run across the street to the garage as well and I moved toward the pedestrian crossing. The guys then saw my plan and stopped in their tracks. They started telling me things like ‘Do you think we want to rob you?’ They tried talking to me saying all sorts of things and then the one guy tried to get closer to me. I said ‘Don’t you dare get closer!’ The guy saw I outwitted them and then started walking away from the bus stop in the direction they were walking and I returned to the bus stop. The other woman who crossed the road then walked to the bus stop when the guys had left and the woman told me ‘They would have robbed you now!’ I said I knew what their intentions were but was prepared for them. But they also saw that I did not have valuable things on me otherwise they would have made the effort to rob me. I only had my bus fare and bank card on me, but they could have taken my cellphone which is what they often target. Another woman approached the bus stop with an expensive gold watch, which is foolish in that area (Melanie, Hector Peterson Residence).

The bus stop where Melanie was nearly robbed falls directly on the threshold between Hector Peterson Residence and the Belhar community. Robbers regularly dwell there. They sometimes disguise themselves as school pupils since a school is nearby, but can also wear balaclavas.

According to Melanie, who grew up in Belhar, suspicious characters look at their victims intimidatingly, as if to make them docile. Robbers also stare at their potential victims thoroughly – looking for possessions on their bodies before they strike. The woman who walked in front of them apparently perceived the same danger and crossed over to the other side of the road. Melanie instead moved to a place where she could more easily escape if the men came too close to her. The men noticed what was happening and remarked that she was wrong – but because they were outwitted, they walked away.

Awareness of a suspicious person is evidently important in staying safe. Due to students’ awareness through stories and exposure, many are able to outwit their ‘predators’ and escape.

Two Fridays after my first arrival in Cape Town in 2003, I walked from campus around 5pm. When I left the station’s side, 6 students walked in front of me but I overtook them because I walked fast. The field was very bushy and as I approached the intersection to the main path that leads to the hostel, I considered which route I should take. As I contemplated this, two guys appeared from behind a bush where they were hiding. I then weighed up the situation and thought it would be best if I walked back in the direction of campus and fortunately there were guys coming from campus walking my way and the two guys ran off into the bushes. They ran off because I told the group of students what I suspected the two guys were up to and pointed at them (Graham, Hector Peterson Residence).

Two men who hid behind bushes on the field were immediately viewed with suspicion. After many complaints from students about the height of the bushes, they are now regularly mowed. Graham’s case emphasises the point that awareness of suspicious behaviour is a tactic of safety. Following ‘instinct’, as Melanie stated, is viewed as a reliable way to stay safe. This was what Graham relied on although he was new to the area. When he told others about the men they disappeared.

In situations where students are uncertain of whether or not a suspicious-looking person may pose a threat, they tend to look for a sign from the oncomer to either confirm their suspicion or refute it. Graham ‘tested’ a suspicious oncomer by greeting him to see what the response would be.

One Saturday evening walking from campus, I was about to swipe myself out of the gate and saw someone sitting close to the entrance with a cellphone. The person looked suspicious and I felt uncomfortable. Weighing up the situation I wanted to stay inside campus, but then just swiped myself out and greeted the guy. The guy returned my greeting and I just walked by. Other times in situations like that I would just start up a conversation with a security guard at the gate until things are settled for me to pass (Graham, Hector Peterson Residence).

Because the oncomer responded by greeting, Graham felt assured that it was fine to proceed, and thus continued walking. Graham generally greets passers-by because it gives him a feeling of control in environments which make him feel unsafe – such as crossing the field or using taxis. His sunglasses also help him to scrutinise oncomers without them realising it.

To Phumzile, oncomers who do or do not greet her also serve to confirm or refute her suspicions – this is in addition to the type of clothes the person wears. However, other types of behaviour also serve this purpose.

As we walked, a guy walked behind us. He wore tekkies, ¾ shorts, a t-shirt and a jacket. We slowed down allowing him to pass. As he passed, I greeted him because people usually greet in return, but this guy did not. So when he was in front of us, he continuously turned back to look at us, and this made him very suspicious. We then walked in such a way as to see if we could get rid of him and walked to Sasol garage. When we came out of the garage, we saw him standing where we had to pass to walk to the hostel. Then some other students who walked with suitcases came and he followed them closely. It was as if he was trying to see what they had on them. I then went to tell someone inside the shop about this guy and they called the police. After that I accepted a lift to the hostel (Phumzile, Hector Peterson Residence).

The clothes someone wears are not a determining factor of present danger. In this case, what was more prominent as an indicator of danger was the man’s strange behaviour: not greeting Phumzile and her friend in return and turning back to look at them continuously. His behaviour was thus out of place for someone not interested in harming them. When he followed them he confirmed their suspicions.

Distinguishing between safe and unsafe spaces

People generally identify violence as occurring in specific places and spaces. Potentially violent spaces tend to be associated with ‘public spaces’. Outside of the ‘public’ domain, that is in ‘private’ spaces, it seems to be more difficult to make sense of violence (Richardson and May 1999: 312). In relation to this, some of the participants felt safer when in the confines of the campus. Phillip experienced being on campus with some ambivalence.

Being on campus does not even feel safe because a friend of mine was stabbed on campus one night. There was even a joke that I heard once, that anybody who walks around late at night is a foreigner and will be killed. This implies then that the locals do not work until late. Even at the gates on campus, people who are not students are let in so easily, while students who occasionally forget their student cards are harassed, even if security staff know the student passed by for years. This makes campus a very unsafe place (Phillip, Hector Peterson Residence).

Being on campus does not necessarily make Phillip feel safe, despite the security staff that patrol regularly. The stabbing of a friend heightened Phillip’s feelings of unsafety. His status as a foreigner and experience of xenophobia strengthened this sense of being unsafe. Furthermore, easy access allowed to outsiders onto the campus increases the risk of the presence of violent people who come to The Barn and to Condom Square, which often results in fights.

Fig.1.3 – The Barn, where students go for drinks and to dance. Fights are known to occur outside after people vacate The Barn

Walking past Condom Square on a Friday night is particularly dangerous because people smoke dagga, get drunk there and loud music is always heard playing there. If anything should happen to me there and I scream, nobody would be able to hear because the music will muffle the sound. One day I even saw condoms and a pair of panties lying there (Catherine, Eduardo Dos Santos Residence).

Figure 1.4 – Condom Square, which is adjacent to The Barn. According to rumours, a woman student was raped here – Photo by author

To the stranger’s eye, The Barn and Condom Square may look like places of relaxation which offer extra-mural activities to students. On weekends one might get a different picture due to the rowdiness, the loud music, the smell of alcohol and marijuana and the poor lighting at night, all coming from the direction of those two places. As a result of this, students feel unsafe, especially when fights break out. Catherine’s fear that if something happens to her nobody will hear, makes her feel unsafe whenever she passes by en route to campus. The sight of a pair of panties and condoms gave her the feeling that forced sex had happened and that she might be in danger. A reported instance of attempted rape also took place on Condom Square when a number of men jumped from the trees and tried to rape a woman student. She managed to free herself. Stories about Condom Square, although not corresponding with what Campus Protection Services report, may also make students feel unsafe. Avoiding such a space is a safety tactic.

The place on campus which seems unsafe to me is the area in front of The Barn, that whole area is unsafe. Last year a lady was raped there by guys who jumped out of the tree (Catherine, Eduardo Dos Santos Residence).

A staff member from Campus Protection Services stated that it was an attempted rape, not a ‘real’ one. The student’s mother wrote a letter to the university in which she made clear that it was an attempted rape case. But students feel unsafe in the area of Condom Square because people get drunk there and become aggressive. Because ‘outsiders’ come into The Barn, students feel unsafe. Women also get drunk and once they leave The Barn, men follow them to their rooms and may ‘take advantage of them’.

I mean you can see people, even if we go there (The Barn) now. … people who, there are those people who do not have cards to go to the tavern, so you don’t know. You can just feel that these people they might do something to me (Khaya, Eduardo Dos Santos Residence).

Coming from Gauteng Province, being in the Western Cape makes Bulelwa feel uncomfortable, especially in the townships. Additionally, Bulelwa feels that being asked on a date may pose danger to her as well, as Xhosa-speakers in the Western Cape ask women out on dates, with sex as their motive. Aware of what happened to her friend when she consented to a date with a man, Bulelwa declines going on dates outside of her sphere of safety.

It is very rough here in Western Cape and there are skollies.When one goes to the townships one cannot talk on the [cell]phone during the day outside in the streets. People cannot wear Levi’s or expensive clothes. This life was never dreamed of. People rob with a knife. People put steel pipes on their faces probably because something happened to them. I usually go to Guguletu to braai there with her friends (Bulelwa, Coline Williams Residence).

Bulelwa’s tactic for safety is to be extra careful when asked out on dates. What happened to her friend refined her ability to distinguish between safety and unsafety.

Men around here (Western Cape), when they take a woman out, especially the Xhosas, they expect sex. They wanted to do this with her but she refused. If men take women out they want to chow them. One friend went to Century City with a man and she did not want to go home with him so he left her there. He then came to fetch her the next day, slapped her and broke her phone. The guys back home will take women out and take them home without chowing them. But a lot of women want to be chowed. If a man wants to get a woman for the night he must take her to the pub and then chow her. This is how men see girls now (Bulelwa, Coline Williams Residence).

Conclusion

This essay addressed various issues around living in a violent environment. Its main argument was that being aware of dangerous spaces and people who may pose threats aid in maintaining safety. At the same time, being aware of potentially dangerous spaces and ‘shady’ characters, may also cause fear among students. In light of this, students use tactics to restore a symbolic order, so that despite the fact that they may be fearful whenever treading in those potentially dangerous spaces, they can use tactics to keep themselves safe. I investigated the idea that there is safety in numbers especially since evidence suggests that group dynamics often influence whether or not bystanders of violence will intervene to help the victim. I found that it is the imaginary safety when in a crowd that creates feelings of safety among students and not being in a group per se. Awareness of dangerous places such as trains that pose danger to commuters often forces students to survive through drastic measures, but prior information helps to reduce chances of fatality. Students would, for example, stay away from broken windows in trains and spread stories which help other students identify potential danger. Of course gender roles and stereotypes influence how people respond to violence since they cause people to behave in certain ways in relation to them. I argue that the environments women grow up in and the absence of messages that counter the perceived ‘weakness’ of women, perpetuate and may exacerbate violence toward them since they challenge and curb potential perpetrators of violence. Women tend to favour the value of male characteristics above their own, which certainly has implications when dealing with violence especially when women are raised to believe they are vulnerable and weak in relation to violence and should rather stay indoors because they are at risk as women. Men on the other hand are taught to believe that they are more powerful in relation to violence and that they will be able to defend themselves. This proves that the social construction of violence is a highly gendered process. Furthermore, stories people hear about violence also increase the awareness of danger and inform the tactics people use to stay safe. Finally, recognising ‘shady’ characters alerts students to oncoming danger and allows them to use tactics for escape or retreat to a safe space. The markers of potentially dangerous characters include strange behaviours, when for example someone continuously turns back and looks at you, or does not greet in return. Recognising such clues helps students escape from potential dangers, but these clues are not static since students may also misrecognise such clues. While this chapter focused primarily on the tactics students use to stay safe in the vicinity of the university, the following chapter addresses the university’s contribution to a safe environment for its students.

—

Published in: Bridgett Sass – Creating Systems of Symbolic Order – UWC student’s tactics to stay safe from potential violence

Rozenberg Publishers 2006 – ISBN 978 90 5170 626 0 – SAVUSA-NiZA Student Publication Series