Photo: www.milaparis.fr

The purpose of this article [i] is to develop an experimental model of deconstruction in CSR in order to attempt to bridge the aporia between the CSR of Jones and De George. Jones advocates the importance of deconstruction in CSR, while De George is suspicious of the perceived relativism and undecidability of deconstruction. It will be argued that this perceived aporia between Jones and De George develops, because it is overlooked by both, that the normative foundation of deconstruction is rooted in the appearance of the other as a function of justice. The appearance of the other decentres business and challenges modernism’s fragmentation and reduction of reality. This is highlighted in Derrida’s deconstruction of the gift in which business is not only a commercial function, but linked to society as a whole and therefore has a responsibility as an agent of social transformation. Deconstruction in CSR will be illustrated in the case study of Royal Bafokeng Platinum.

1. Introduction

The debt crisis of 2008, corporate scandals and environmental disasters related to business activities have emphasised the importance of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a means to encourage good corporate citizenship. Good corporate citizenship assumes that business has a responsibility in society. This means that business will not harm society or the environment and assist in transforming society. This can be done by business by means of using their wealth and expertise to improve the lives and circumstances of people and by addressing injustices like socio-economic inequality. Corporate citizenship affirms the complex nature of corporate responsibility that encompasses a wide range of stakeholders in the local and global context e.g. Stakeholder theory[ii] (Freeman 1984). In this context, some scholars have argued that deconstruction, and specifically the work of Jacques Derrida in terms of the ethics of irreducibility, responsibility and justice, may be insightful to CSR in the global business context of cultural and religious diversity by challenging the limits of traditional CSR (Rendtorff[iii] 2008, Jones 2007, Woermann[iv] 2013). Limits refer to the focus of deconstruction on the inability of language to articulate the full complexity of reality (Melchert 2011:700). The optimism that articulation is possible, is a legacy of the reductionist trend of modernism and science that is evident in traditional CSR (Woermann 2013:98). Traditional CSR is rooted in the assumption that profit is the main agenda of business and the focus of social responsibility and ethical decision-making. Therefore, universal normative foundations are required to provide homogenous and predictable outcomes that sustain the status quo. According to this view, business only has a commercial function in society and the interaction of a business with employees, clients, producers, shareholders and communities is ultimately to increase profits and has very little to do with justice and social transformation, except indirectly though compliance to legal and other demands of society. Thus, traditional CSR is a phenomenon of modern culture that perpetuates a reductionist and fragmented view of reality and society in which business mostly focusses on profit and compliance, as if business is not linked to all other aspects of society (Taylor 2003:1-12). This fragmentation does not imply that traditional CSR is redundant and irrelevant, or, that deconstruction is against traditional CSR. Deconstruction reveals that business is more intertwined with society and cannot be limited to profit-making alone, or that transformation is only the responsibility of government. Deconstruction uncovers the tensions within traditional CSR between business as commercial function and agent in social transformation. This tension is due to the fragmented view of reality of traditional CSR that limits business to profit-making, while excluding the possibility of other functions. This is highlighted by Derrida’s deconstruction of the gift that views business as a commercial enterprise and social institution for the benefit and transformation of society. Thus, deconstruction acknowledges the complex and socially connected status of business in society and that business is an agent of social transformation, amongst others.

The problem is that the role of deconstruction in CSR is aporetic[v] and under negotiation because of the criticism, from traditional CSR theorists, who claim that deconstruction undermines the integrity of CSR because of the perception, amongst others, that deconstruction is relativist and lacks a normative foundation for business decision-making. Therefore, some scholars embrace deconstruction and explore the possibilities it has to offer CSR; while others are sceptical and view aspects like irreducibility as a danger to responsible business practices. In this study, the focus will be limited to the research of Campbell Jones that explores the opportunities that deconstruction has to offer CSR to become an honest practice that reveals the aporetic nature of CSR; and Richard T. De George’s traditional[vi] CSR, that responds with extreme suspicion of deconstruction because of its perceived inherent undecidability and relativism that undermine the commercial function of business. The conflicting views on deconstruction of Jones and De George highlight the (im)possibility of normative foundations in CSR. In other words, the problem is that, according to Jones, the suspension of normative foundations of traditional CSR and the elusiveness of decision-making are important contributions of deconstruction; while De George rejects deconstruction because it undermines the possibility of universal normative foundations and decision-making in CSR. Thus, the question remains whether deconstruction has a normative foundation that can contribute to justice and transformation.

The hypothesis of this study is that the appearance of the other as a function of justice and transformation is the normative foundation of deconstruction that is imbedded in the practice of CSR. In other words, deconstruction in CSR can decentre traditional CSR, thus, opening the possibility that business can be a function of justice and social transformation. This outcome is possible if business is viewed as an integral part of society and important agent, amongst others, in social transformation. Although Jones’s aporetic position has a more holistic view of business in society, he unfortunately does not explore the constructive dimension of deconstruction as a function of justice and social transformation in his article. It will be argued that a key strength and normative aspect of deconstruction comprise the possibility of transformation with the appearance of the other. However, for business to contribute to social transformation, the normative dimension is located on the margin, the other, beyond the centre of society. If the other is merely an aspect of society, it leaves little room for transformation. The other then becomes one among many other stakeholders. Social transformation is far more inclusive and affects society as a whole and business as an aspect of society when the other appears. This is the strength and normative aspect of deconstruction. Recognition of the other creates the possibility of justice and change. This hypothesis is presented with the full awareness that the reference to normative foundations is already under the sway of deconstruction itself. However, it will be argued that the sway of deconstruction is rooted in the possibility of justice that is beyond the finality of the law. Deconstruction highlights that CSR is an immanent event and that the normative foundations of CSR are embedded in this event through the appearance of the other that transforms society. Thus, deconstruction resists stakeholder engagement that attempts to manage CSR by means of erasing stakeholders who appear and challenge the status quo. The inconsistencies that result from the appearance of the other is the basis of justice that challenges the law and results in the possibility of social transformation and CSR that is practiced with philosophical integrity (Rossouw 2008). Thus, deconstruction has a constructive dimension that will highlight that CSR is an immanent phenomenon that is able to critically manage the inconsistencies and peculiarities of real situations by engaging the other without regressing into the safety of universalism and reductive rationality. In other words, deconstruction highlights that CSR is an act of hospitality that welcomes the other as a function of justice and critically manages the complexity of stakeholder engagement. In order to develop this constructive view of deconstruction in CSR, a clear heuristic definition of justice in CSR is necessary to assist practical implementation and decision-making. In other words, the appearance of the other as a function of justice is the normative dimension in CSR. However, this notion of justice must be clearly articulated to assist business to be conducted in a transformative manner. Thus, the following heuristic definition will be proposed that will form the basis of an experimental model of deconstruction in CSR: CSR is a critical immanent event that has the possibility of social transformation through the engagement with stakeholders in order to challenge the traditional functioning and decisions of business. In other words, CSR can be a function of justice and social transformation.

In section one of this study, is a discussion of the article of Jones entitled Friedman with Derrida (2007) that highlights the positive contribution of deconstruction. Secondly, follows a discussion of De George’s criticism of Jones and deconstruction in the article, An American perspective on corporate social responsibility and the tenuous relevance of Jacques Derrida (2008). The third section consists of a reflection on the appearance of the other as a function of justice as the normative foundation of deconstruction with special reference to the gift and hospitality; and the implications of deconstruction in CSR for business and society. In section four an experimental model of deconstruction in CSR will be proposed, unpacked and illustrated by a case study of Royal Bafokeng Platinum (RBP).

2. Campbell Jones

In the article Friedman with Derrida (2007), Jones highlights the contribution of deconstruction to CSR by deconstructing Friedman’s shareholder approach to CSR. The shareholder approach of Friedman is usually criticised by stakeholder theorists for reducing corporate responsibility to profit-making and compliance to laws and regulations (Stone 1992:442-443). Friedman is synonymous with the following quote that appeared in a 1970 New York Times Magazine that describes CSR in a “free society”: “There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud” (Friedman 1962:133; 1970:126). This highlights the role of compliance in the law of shareholder CSR. However, according to Jones (2007:514), this quote is often misused by representatives of the stakeholder theory to construct a shareholder/stakeholder dichotomy. The problem is that this opposition between shareholder/stakeholder perspectives forms the basis of a binary opposition in which one view is prioritised over the other (Jones 2007:514). Friedman’s view of CSR, according to Jones, is thus reduced to the title of his 1970 article that appeared in the New York Times Magazine.

However, in Friedman’s 1962 work entitled Capitalism and Freedom (1962), the same quote appears with a different context in mind. In Capitalism and Freedom (1962) the quote refers to “a free economy”, and the 1970 New York Times Magazine article uses the quote to describe “a free society” (Jones 2007:515). In other words, Friedman refers to two different things in the two texts but uses the same quote. Further, in Capitalism and Freedom (1962) the quote is followed by the following: “Similarly, the ‘social responsibility’ of labour leaders is to serve the interests of the members of their unions” (Friedman 1962:133). Thus, in the context of “a free economy” responsibility is divided and represented by two parties, namely: “corporate officials” on the one hand; and “labor leaders”, on the other (Jones 2007:517). Therefore, Capitalism and Freedom (1962), does not contain a unified view of CSR, as is suggested by Friedman in the New York Times Magazine article. CSR involves at least two sets of responsibilities that are in tension with each other. In other words, to reduce Friedman as representative of a shareholder view of CSR based on this popular 1970 article is misguided, because there is something “subversive” in Friedman’s understanding of CSR, as is reflected in Capitalism and Freedom (1962).

The point that Jones attempts to make is that there is a deconstructive movement in Friedman’s texts that destabilises the neat reductionist boundaries that are erected by the binary strategy of stakeholder theorists. Jones (2007:521-522) concludes: “The point, rather, is that whether we like it or not, Friedman is in deconstruction. Friedman’s text struggles with a set of claims and counter-claims that are inconsistent and at odds with themselves” (Jones 2007:521-522). In other words, Friedman is demonised by stakeholder theorists in order to emphasise the importance of their positions. This is the crucial contribution of deconstruction according to Jones: “Deconstruction involves not avoiding such tensions or seeking to make them manageable….” (Jones 2007:522). Thus, deconstruction emphasises the fact that decisions are “difficult and not reassuring” because they always remain under negotiation and are at most preliminary (Jones 2007:522). This important aspect of deconstruction, according to Jones (2007:518), has been widely used in management and organisational studies. However, in business ethics[vii] and CSR, little attention has been paid to the possible contribution of deconstruction (Jones 2007:519). According to Jones, this is an oversight because deconstruction can be helpful when “negotiating with contamination” by “showing, documenting, and demonstrating the instability of specific boundaries” (Jones 2003:520). Deconstruction has the ability to reveal the complexity of reality without ending with reductive methodologies. Deconstruction deals with the dynamic and temporal nature of reality. Jones (2007:520) highlights that “deconstruction is not a ‘method’ that could be ‘applied’ to another object”. Deconstruction “is applied; it is always ‘at work’” (Jones 2007:520). Deconstruction is radically located in time and space. It is radically immanent. It is something that happens when theories, models and applications are created. The moment we write an idea, deconstruction is at work in the negotiation between the inside and outside of the boundaries we need in order to articulate our thoughts. Thus, deconstruction is not an instrument of modernity with methods to provide clear calculations to problems faced by business. It rather prepares business for the transformational process involved in CSR because “deconstruction is always already at work” (Jones 2007:521). Jones (2007:523) notes that deconstruction is at work in the “already contested and aporetic space of CSR”.

The active presence of deconstruction in CSR is an honest acknowledgement that the universal foundations of traditional CSR implodes under the strain of reality brought about by the appearance of the other. Deconstruction is an honest acknowledgement of the tension already at work in CSR (Jones 2007:524). Jones (2007:524) notes that the question of the other, is related to the work of Levinas[viii] and his critique of Heidegger’s understanding of responsibility from the perspective of the subject. Responsibility, according to Levinas, is relational[ix]. Jones (2003:227) stated in an earlier study that it “….involves a recognition and openness to the face of the Other, which entails as Derrida puts it, ‘a total question, a distress and denuding, a supplication, a demanding prayer’” (Jones 2003:227). Deconstruction exceeds “calculation of advantage, of expectation of reciprocity and of reasons….” (Jones 2003:228). Deconstruction “proceeds not from an autonomous subject, but at the point at which the autonomy of the subject collapses”. Responsibility, according to Jones (2007:524), “involves a response to a call from the other person and that justice involves the impossibility of negotiating the demands of more than one Other, Derrida poses the questions of responsibility in terms of ‘whom to give to’”. Openness to the other is the basis of honest CSR practices because deconstruction is the emergence of “undecidability” as a characteristic of ethics, politics and justice (Jones 2007:524-526). Jones (2007:516) states that in the work of Derrida, responsibility is not positioned in the space of certitude but undecidability. “One is only responsible when one is not sure if one has been responsible” (Jones 2007:526). Thus, CSR is not to “get on with the business of responsibility”, rather, responsibility is when “impossibility, radical undecidability and the lack of coherence at the heart of CSR become a priority”, according to Jones (2007:526-528). In other words, the other continuously appears as part of society (e.g. stakeholder) by challenging business without reaching a point of finality.

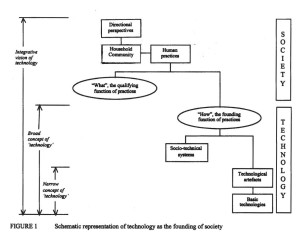

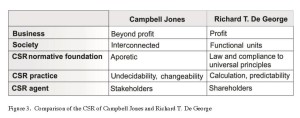

Jones (2007:514) is very optimistic about the contribution of deconstruction as a means, amongst others, to engage aporia present in CSR (e.g. the tension between shareholder and stakeholder CSR); and, as a means to understand the limitations of CSR. Jones embraces deconstruction as a means to maintain the philosophical integrity of CSR by arguing that deconstruction expands the limits of responsible business practice. This is done by the appearance of the other that requires further ethical reflection which goes beyond the traditional limits of CSR like the avoidance of risk, amongst others. In other words, deconstruction is critical of the reducibility of traditional CSR. Deconstruction challenges traditional CSR and its universal foundations that focus on increasing profitability and limiting the risk of corporate scandals. Jones tests the limits of CSR, which may seem to reach a point of implosion by decentring the notion of responsibility by the proliferation of stakeholder engagement beyond traditional boundaries. However, the crucial aspect of deconstruction is the assumption that the appearance of the other is already happening and destabilising tradition CSR. Deconstruction through engagement with the other is already transforming business. Thus, the challenge of deconstruction is unavoidable, according to Jones, to honestly acknowledge the aporia already present in CSR and to refrain from reductions and calculations that support the short-term goals of business. This reference to honesty is important because it is reminiscent of the virtue ethics of Aristotle, but this aspect is not developed as a foundation for CSR. For Jones, foundations remain elusive and therefore CSR is aporetic. Unfortunately, Jones does not develop a normative

Figure 1: CSR as aporetic

aspect or stipulate how responsibility and the other can provide a normative foundation for justice and transformation in the practice in his aporetic CSR (See Fig. 1). For Jones, the other appears as stakeholders who challenge business to move beyond a commercial function. The radical aspect of the other as a change to society as a whole and business specific, as a function of justice and transformation remains undeveloped. In Jones’s article the face of the other becomes an abstract concept that destabilises business activity and may result in the spectre of relativism. These aspects of undecidability and relativism take centre stage in De George’s criticism of Jones.

De George, in the article An American perspective on corporate social responsibility and the tenuous relevance of Jacques Derrida (2008), is critical of Jones’s optimism of the usefulness of deconstruction for CSR. De George’s critique of Jones starts by focussing on the contextual differences between business ethics and CSR in the United States of America and Europe. He argues that the social dimension of European business may be more open to the role of deconstruction. Next, De George contextualises Friedman’s shareholder CSR in an attempt to highlight the inconsistencies of Jones’s deconstruction of Friedman that ends in undecidability and relativism.

In the United States, according to De George (2008:74), the focus of business ethics is on individual morality and ethical theories like those of Kant, Mill, Aristotle, Rawls, pragmatism, feminism, theories of rights and justice. In Europe, corporations are integrated into the social fabric of society and employees receive more social benefits (De George 2008:74). The difference between CSR in the United States of America and Europe, according to De George (2008:80), has to do with the structure of society. De George (2008:80) notes that in the United States of America the focus is on the individual and “the actions of individual corporations or business executives” (De George 2008:80). This differs from Europe that has a stronger social focus reflected in the structure of society and “the business-government relation” (De George 2008:80). In other words, the focus of deconstruction on social issues and justice is probably more adapted to the European context. According to De George (2008:80), the task of deconstruction of looking for “hidden contradictions” in foundational structures, characteristic of Western thought since the Hellenistic times, is an attempt to undermine accepted beliefs and presuppositions of business in the United States of America. De George (2008:80) notes that this demonises deconstruction as the antagonist of what is acceptable. Therefore, the agenda of deconstruction is foreign to the context and seems like an attempt to undermine the value of business in the United States of America. The negative effect that deconstruction may have on business highlights De George’s traditional view of CSR that is rooted in individualism and free-market capitalism.

De George (2008:75) argues that the 1970 article of Friedman is a response to ideas related to the development of CSR in the United States of America that goes beyond a reductive focus on profit. Rather, it was influenced by contextual events like World War II, environmentalism and the Vietnam War. Friedman responds to these events in his 1970 article in order to give a “… voice to a number of business people who felt an incompatibility between their business responsibilities and the new demands that were being thrust upon them” (De George 2008:76). Friedman, according to De George (2008:76), therefore argued that economic, legal, social, environmental and other expectations that are demanded by society go beyond the purpose of business. The strategy of De George is to undermine the argument of Jones in terms of its subjectivity and failure to deal with the historical situation to which Friedman responds. From this, De George’s focuses on globalisation and diverse social expectations and the opportunism of interest groups that may use CSR for political gain.

De George (2008:76) notes that although moral and ethical responsibility always remains the same no matter what culture or context the business operates in, globalisation changed the way CSR functions. The reason for this is that CSR is context specific and reflects the “expectations and demands of the societies in which the corporations are found and/or where they operate” (De George 2008:76). CSR is influenced by the demands that society places on business as a result of “conventional morality” that goes beyond the law (De George 2008:77). Thus, stakeholder engagement has to deal with societal differences that may be the result of history, culture, gender, geography and other factors. According to De George (2008:77), the difficulty that corporations face is to make a distinction between societal expectations and what is written into law. CSR is complicated by the role of interest groups who use sophisticated rhetorical mechanisms that manipulate businesses to support their particular agendas, although it may not seem to be in the general interest of business or society to do so. The expectations that business has to deal with may be those of minorities who because of their influence, force business to adhere. Thus, societal expectations may be opportunistic and in many cases beyond the expectations of law. Deconstruction and the role of the other support the opportunism of minorities (De George 2008:77). This, according to De George (2008:77), is clear from the example of pharmaceutical companies that refuse to provide anti-retroviral drugs to Africa while they publish glossy magazines promoting CSR[x]. The problem, according to De George (2008:77), is that it is unfair to make these companies solely responsible for the burden of HIV/AIDS (De George 2008:77). De George is correct that opportunism and the politics of interest groups may detract from CSR. However, it is an open question whether deconstruction and the other can simply be reduced to opportunism.

The universalism of traditional CSR becomes more apparent in De George’s criticism of the lack of normative foundations of deconstruction and the danger of undecidability present in Jones’s deconstruction of Friedman’s shareholder CSR (De George 2008:81). De George (2008:81) states that the deconstruction of Friedman by Jones evokes and provokes. It evokes Hegel’s master/slave dialectic and Marx by claiming that Friedman presents two responsibilities in Capitalism and Freedom (1962) namely, corporates and labour unions that emphasise the socialist context of European CSR. The article also provokes by claiming that “Friedman does not know what he is talking about” when referring to a “free economy” and “free society” (De George 2008:81). However, according to De George (2008:81), this provocation is a subjective and inaccurate interpretation of Friedman because the reference to a “free economy” and “a free society” in terms of shareholder responsibility, is the “same whether one speaks of a free economy or of a free society, which for him requires a free economy” (De George 2008:81). Thus, it is misleading, according to De George (2008:81), to refer to a slippage or lapse in Friedman’s use of the quote that refers to shareholder responsibility.

Positively, De George (2008:81) acknowledges that the binary strategy between labour and capital used by stakeholder theorists is exposed by Jones. However, this is as far as he is prepared to go because according to him, the notion of the other and social change is beyond the purpose of CSR. De George (2010:200) states that “… although corporations are created to serve the common good, it does not follow that an appropriate end of every corporation is the improvement of general welfare, except by its appropriate business-related activity” (De George 2010:200). Thus, direct social change is beyond the responsibility of corporations. Justice and transformation is the responsibility of individuals and governments. CSR focuses on containment, according to De George (2010:201). CSR is a mechanism to limit the harm that corporations may cause society and the environment in their business activities. Corporations are mainly indirect agents of change by complying with the legal and policy demands of a society (e.g. Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) in South Africa). In other words, corporations mainly have a commercial function in society. Corporations are separate entities with the purpose of profit-making, and CSR is a way of enhancing the business objectives of corporations with the least harm to society. This reflects the modern tendency of traditional CSR that fragments society and CSR. Traditional CSR has to do with corporations and not justice or social transformation because corporations are not viewed as agents of transformation in society.

The traditional CSR of De George follows the fragmentary view of society that consists of various components of which business is a part. This traditional perspective of De George is emphasised by his criticism of deconstructions, perceived relativism and undecidability. De George (2008:83) is unnerved by the fact that Derrida does not have an ethical theory in line with classical modern ethicist (e.g Kant, Mill, etc.). De George (2008:83) opines of Derrida, “His aim is not to explain and justify any existing morality, conventional or otherwise, or to propose an alternative morality”. According to De George (2008:83), Derrida disrupts traditional ethics (Aristotle, Kant, Mill, Marx and Rawls), because he questions foundationalism that results in the absence of “rules to follow or duties prescribed” (De George 2008:82). In other words, for De George, deconstruction is a disruptive philosophy that undermines the normative foundations of ethics and CSR because it does not offer universal answers to ethical problems. The consequence is that CSR and business are left with more questions than answers. However, this inclination to provide answers is an attempt to stabilise and re-assure business of the corporate agenda of CSR. This re-assurance highlights that business aspirations are the central agenda of CSR. Thus, the relativism of deconstruction has practical implications for business because it is not clear that “…. Derrida recognizes any objectively right action, and hence one is always unsure because there is nothing to be sure about” (De George 2008:82). It seems that, according to De George (2008:81-82), deconstruction may lead to CSR that succumbs to “undecidability”. De George (2008:82) states, “The unsettling aspect of the act of deconstructing, however, is that we seem never to get an answer, and that whenever we arrive at an answer we are assured that it must be wrong. This makes informed action difficult, if not impossible, and reduces those in business who have to make decisions, or their critics, to the position of an undecided Hamlet”. In other words, deconstruction embraces undecidability at the expense of decisions, action and conclusions.

However, according to De George (2008:82), the “task of CSR is a different task, namely influencing those in business to act in a way that is more positive in its effects on human beings, on the environment, on the common good than is often the case .…”. The aim of CSR is “tampering the destructive and rapacious tendencies of unregulated big business, and has had some success in curtailing some practices harmful to people. To the extent that if it has had any success in improving the lot of human beings, CSR is a positive force in the business arena, even if poorly understood by its practitioners, even if rife with irresolvable conflicts, and even if it is in the process of deconstructing itself” (De George 2008:83). Therefore, the challenge that CSR must be open to the other makes little sense because businesses are “… engaged in production and exchange. For profit organizations are by definition self-interested entities. They are not formed to give away what they produce as gifts. They do not open themselves up hospitably and risk being taken advantage of by anyone who chooses to do so” (De George 2008:84). According to De George, the other is the antagonist of business and CSR. Business has a commercial function in society and therefore the other only interferes with this function.

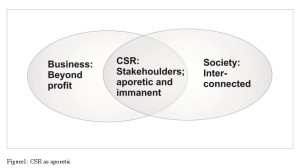

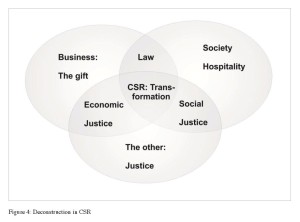

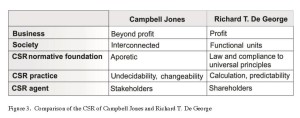

Figure 2: CSR as compliance to the law

To conclude, De George (2008:85) states that Jones “wants to change business practices with respect to exploitation, pollution and other areas”. However, “his adherence to Derrida’s approach does not permit such wholesale condemnations or judgements about what is right and wrong” (De George 2008:85). Jones is “against business ethics”, according to De George (2008:85). The undecidability and relativism of deconstruction are major problems for De George (Woermann 2013:103). The reason for this is that it lacks clear normative guidelines for application and is more orientated to social issues like in the case of business in Europe. Another aspect that De George raises is that, although deconstruction contributes to philosophy and literary theory, it is in conflict with liberal ideas of business practices e.g. self-interest and profit. In other words, De George’s fragmented view of society, the yearning for universal values, and decidability reflect a traditional view of CSR. CSR contributes to the function of business to make profit and compliance to legal directives (See Fig. 2). In the next section, it will be argued that the normative foundation of deconstruction is the appearance of the other as a function of justice and social transformation. This will become clear in the deconstruction of the gift and hospitality as key concepts that Derrida uses to discuss the economy, thus addressing the criticism of De George.

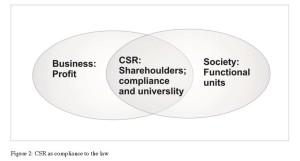

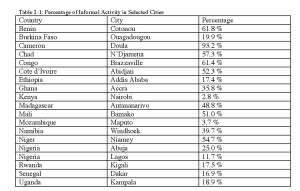

Figure 3. Comparison of the CSR of Campbell Jones and Richard T. De George

4. Deconstruction in CSR and Justice

The conflicting views on deconstruction of Jones and De George highlight the (im)possibility of normative foundations in CSR (See fig. 3). On the one hand, Jones is critical of the universal normative foundations of traditional CSR that fails to respond to the other, and on the other hand, De George attempts to selvage traditional CSR because of its usefulness for business. The absence of universal foundations in deconstruction is his major criticism of deconstructions in CSR. Thus, the question is whether deconstruction has a normative foundation that can contribute to justice and transformation.

Jones focuses on the ability of deconstruction to expand traditional notions of responsibility that reduce stakeholder interaction to universal categories. Thus, deconstruction assists CSR to be practised with honesty. Honesty refers to the acknowledgement that reality is complex and cannot be reduced to universal categories. Honesty requires ethical reflection within the situation and the ability to manage inconsistencies and tensions. In other words, for Jones the level of honesty is what separates traditional CSR from deconstruction because universalism and rationalism are tools to reduce the complexity of stakeholder interaction. However, Jones does not delve into the philosophical challenge of deconstruction that deconstructs traditional CSR, society and business. This challenge is rooted in the normative foundation of deconstruction that focuses on the transformation of business and society beyond the fragmented[xi] view of reality and society that forms the foundation of traditional CSR. Thus, the perception remains that deconstruction can be viewed as an antagonist of business, rather than an inspirational moment of change and justice.

De George is suspicious of the possible lack of normative foundations of deconstruction because it may undermine the usefulness of CSR for business[xii]. De George associates responsibility with individuality, rationality and universalism as the basis for stakeholder interaction. However, at a philosophical level this perspective is rooted in modernism and a fragmented view of reality that separates business and society[xiii]. Thus, responsibility is bracketed in terms of the rational engagement that has the potential of positively affecting the moral behaviour of business because business is part of society in general, and is more than a profit-making machine with no possible role in social transformation.

At this point it is crucial that Derrida’s view of responsibility is explored in order to ascertain whether deconstruction does provide normative foundations for change. It will be argued that deconstruction highlights the fact that justice as a function of the appearance of the other is the normative foundation for social transformation that is imbedded in the practice of CSR. Although Jones develops the role of deconstruction as an honest CSR practice, he fails to develop the role of deconstruction as a means to transform fragmentation the fragmented view of society that reduces business to a commercial function. Thus, the normative foundation of deconstruction that decentres business and the fragmentation of modernity are not explored. This process of decentring views business as an integrated part of society with the ability to participate in social transformation and justice. The discussion of deconstruction, its view of the economy and justice in the next section will reveal that deconstruction in CSR is a critical immanent event that has the possibility of social transformation through the engagement with stakeholders that challenges the functioning and decisions of businesses.

4.1 Deconstruction, justice and social transformation

Deconstruction is mainly associated with the work of Jacques Derrida and post-structuralism (Melchert 2011:700-703). Deconstruction developed as a linguistic theory that aims to reveal the limits of metaphysics[xiv], associated in Western culture with logocentrism[xv] – the presence of the spoken word. The priority placed on presence in Western culture is also highlighted by the notion of dasein or “being here” of Heidegger. Derrida highlights that presence is only constructed on the basis of the absence of the other. In other words, any text is an ideological construction with a central thrust or strategy that marginalises the other. The aim of deconstruction is to reveal this hierarchical construction of reality that is reflected in linguistic reality. For example, the patriarchal gender role of male/female is built on the priority given to the male side of the dichotomy. Deconstruction interrupts this construction by emphasising the presence of the female or other. Thus, deconstruction is a moment of justice that exposes patriarchal gender stereotypes. This has important implications for applied ethics, because there is a critical moment that incorporates justice as a means of transformation in the process of ethical decision-making. In other words, applied ethics is not merely understood as the practical implementation of good moral practices. It actually goes a step further by revealing and transforming unjust moral practices, thus expanding applied ethics and its philosophical integrity. In this regard, the entry of the other is the normative foundation for justice and the constructive basis for transformation.

Derrida (1972:xiv) highlights the constructive dimension of deconstruction by stating that it “…is not a form of textual vandalism designed to prove that meaning is impossible. In fact, the word ‘de-construction’ is closely related not to the word ‘destruction’, but to the word ‘analysis’, which etymologically means ‘to undo’-a virtual synonym for `to de-construct’. The deconstruction of a text does not proceed by random doubt or generalised scepticism, but by the careful teasing out of warring forces of significance within the text itself. If anything is destroyed in a deconstructive reading, it is not meaning but the claim to an unequivocal domination of one mode of signifying over another” (Derrida, 1972:xiv). Deconstruction is not rooted in abstraction but the singularity of a contextual event. In terms of the example of patriarchy, deconstruction is activated in the event of patriarchal gender stereotyping by the male/female dichotomy. The aim of deconstruction is to reveal the marginalised other in the construction process. Thus, deconstruction is immersed in the singularity of a particular situation.

The situational aspect of deconstruction highlights the complexity of reality as its starting point. This reality cannot be reduced to ethical calculation, because it is a human reality that is continually challenged by the face of the other. It is immanent, involved in the here and now of the situation, and the faces of all involved. It does not succumb to generalisation or universality. However, it is in the moment that the face of the other appears as critical intervention in the ideological strategies of the centre. Justice acknowledges that the hierarchical engagement between centre and margin can only be transformed when the other appears. Thus, justice resides in the “disjuncture of the ethical relation with the Other” (Woermann 2013:113). The appearance of the other requires a decision to respond or refrain from responding. Woermann (2013:116) states that justice is the “moment of decision”. Thus, De George’s criticism regarding the danger of undecidability and relativism of deconstruction is undermined. Woermann (2013:107) states that deconstruction is “not a relativist stance, but a modest stance geared towards openness for otherness”. This notion of justice has the constructive potential to bring about transformation in society. Deconstruction does not succumb to relativism, as may be inferred from Jones’s aporetic CSR. It has a constructive moment of justice that results in social transformation. This transformational aspect is clearly introduced in the deconstruction of the gift.

4.2 The gift and hospitality

The gift is important because it reflects Derrida’s view of the economy. The gift, according to Derrida (1991:18), consists of a binary relationship between giving as an act that perpetuates the economic cycle, and giving as an act of intervention without re-appropriation in the economic cycle – a moment of justice. The former refers to giving that pre-empts a response from the receiver. This response stimulates the economic cycle. It is a gift that is not a true gift in the Kantian sense (Goosen 2007:179). The true gift is transcendent. A gift is a sacrificial act that is beyond self-interest (Goosen 2007:179). Goosen (2007:180) notes that this perspective denies all forms of reciprocity and interdependence. The gift is a sublime-unilateral event in which the subject becomes a passive recipient (Goosen 2007:181). In other words, it is giving without expectation of a response. Derrida (1991:18) states that “the gift is precisely, and this is what it has in common with justice, something which cannot be reappropriated”. In other words the gift is an act of justice. Thus, the “…‘idea of justice’ seems to be irreducible in its affirmative character, in its demand of gift without exchange, without circulation, without recognition of gratitude, without economic circularity, without calculation and without rules, without reason and without rationality” (Derrida 1991:55-56). However, this gift is not the result of duty. It happens with the appearance of the other. The presence of the other triggers the gift and the possibility of justice. Caputo (1997:149) notes that “justice is the welcome given to the other in which I do not, as far as I know, have anything up my sleeve; it is hospitality…”. Thus, the narcissism of the economic cycle is interrupted by the appearance of the other that requires hospitality.

Hospitality transcends the boundaries of communities by opening up traditional ideas of inside and outside – it is when the other is recognised. Recognition makes intervention and hospitality possible. It emphasises that the arrival of the other results in transformation and the re-evaluation of limits – inside and outside. It transforms the inside. Derrida (1995:199) refers to this as hospitable narcissism. Derrida (1995:199) states that there are various degrees of self-love or various economies of narcissism – “There is not narcissism and non-narcissism; there are narcissisms that are more or less comprehensive, generous, open, extended….”. The more “comprehensive narcissism” is hospitable narcissism, thus, “…one that is much more open to the experience of the other as other” (Derrida 1995:199). Caputo (1997:149) refers to “hospitable narcissism” as “interrupted and ruptured narcissism”. The appearance of the other interrupts “uninterrupted narcissism” or contemptible crude self-interest. The point is that all love starts from self-love. It makes love of God and the other possible – “a movement of narcissistic reappropriation” (Derrida 1995:199). Without this reappropriation, the relation to the other will be destroyed. What is necessary is “a movement of reappropriation in the image of oneself for love to be possible…. love is narcissistic” (Derrida 1995:199). Therefore, for the gift to remain a gift, the narcissism of the cycle must be broken by what is absent – giving without self-interest, a moment of madness or sacrifice when the other enters the cycle and disrupts the narcissism. It is the moment when the gift is given without reappropriation – forgetting that a gift was ever given. The economic cycle and hospitality is crucial for a gift to be a gift. The one cannot exist without the other because the economic cycle without intervention becomes narcissistic and self-destructive. The implication is that the gift annuls itself because the moment the gift is a function of a reciprocal cycle, it is no longer a gift (Derrida 1991:11-12). Then the gift turns to poison – die Gift vergiftet (Caputo 1997:141). In the same way giving without response destroys the gift. When everything is a gift, the gift disappears and the gift is annulled. However, the appearance of the other is bound to time and space – it is an immanent or contextual event. It also contains a transcendent aspect reflected in the sacrificial act of giving that happens when the other appears. Stoker and Van der Merwe (2012) refer to this paradoxical character of deconstruction as immanent transcendence. The appearance of the other as a function of justice is a normative aspect that requires a decision – hospitality. This is beyond the stakeholder engagement of Jones that results in undecidability. It is a transformational moment. Thus, deconstruction highlights the possibility that business is not limited to the economic cycle and profit-making because business without hospitality, will destroy the aims of business. Business is part of society and has a role to play in justice and transformation. The role of justice and transformation with the appearance of the other has important implications for CSR as a vehicle for change.

4.3 Deconstruction in CSR

Contemporary CSR theory emphasises the role of stakeholder engagement. In other words, it highlights engagement with the other. The problem is that rationalism and universalism result in CSR that does not invoke change and justice. It affirms business as usual. In other words, CSR and stakeholder engagement can become a self-serving programme that does not bring about transformation. This may be the unfortunate implication of Jones’s aporetic CSR that results in no transformation because of undecidablity or strategic stakeholder engagement (Porter & Kramer 2006). Paine (2003:327) warns that this approach conceals a dangerous undertow. “On the surface, ethics appears to be gaining importance as a basis for reasoning and justification. At a deeper level, however, it is being undermined. For implicit in the appeal to economics as a justification for ethics, is acceptance of economics as the more authoritative rationale. Rather than being a domain of rationality capable of challenging economics, ethics is conceived only as a tool of economics”. CSR becomes an institutional tool that affirms institutional values. The gift that transforms nothing is a clear departure from the economics of Adam Smith that highlights that both sympathy and self-interest are the basis of a moral society (Sen 1999:27-28).

Moriceau (2005:97) states that institutionalising CSR into a series of measures, standards and ratings is turning investors and directors away from the faces of stakeholders. CSR is emptied of its quality of commitment, and of a certain kind of responsibility towards issues in society. This is exacerbated by the sway of modernism that passes social responsibility on to specialised entities. In other word, standardisation and specialisation are increasing the distance between companies, investors and other stakeholders. The problem, according to Moriceau (2005:97), is that the construction of stakeholder types is already alienating because it constructs a common type. However, responsibility is singular, facing someone. “It is something eminently singular, a proper noun rather than a common noun” (Moriceau 2005:97-98). Traditional CSR constructs universal types of stakeholders that may result in depersonalisation and the error of omission of stakeholders that fall outside the constructed categories. The face of the other is erased and constructed into a controllable essence. Thus, responsibility becomes abstract, sterile, predictable and decidable. Traditional CSR can reduce reality, humanity and life to matters of mechanical processes, complying with a tick-list and prescribed functions of responsibility without changing anything. However, undecidability, as is the case with Jones, may lead to malaise without transformation. Facing the other challenges business; it requires interruption and the gift as a hospitable response to the chaos of injustice. The appearance of the other requires a decision that has the ability to transform society and the lives of people. It does not remain in a space of undecidability. It requires reflection, balancing goals and guidance. This decision does not involve calculation according to modern rules, but rather engagement and hospitality. The decision “remains to be invented, to be brought into existence. Deciding means producing a possibility” (Moriceau 2005:100). Deciding is ethical and deals with the complexity and impasses of reality. Thus, CSR and the contribution of deconstruction fail if they are not located in the present, singularity of the situation in which transformation happens.

However, according to Derrida (1995:199), the other is already present in the situation. Hospitable narcissism is what makes the economy possible and at the same time interrupts it as an act of justice. Deconstruction in CSR decentres business and transforms society as a continuous act. It is not about CSR that advances the programme of the corporate business or a space of malaise. It is CSR that has the possibility to expand the scope of business beyond self-interest (Rendtorff 2008, Paine 2003). In other words, the other appears and interrupts the narcissism of traditional CSR. According to Derrida, this is an act of madness, because it interrupts the economic cycle or the strategic goal of business with a gift – the Kantian transcendental moment. The interruption implies that business is an important aspect of society and agent of social transformation. However, the moment of interruption does not arrive out of guilt. It arrives as a consequence of the interconnectedness of society and the singularity of the event. The tension between the economic cycle and hospitality erupts. The economic cycle deconstructs under the fragility of its narcissism. In this way, CSR has the potential to bring about social transformation. The traditional CSR of De George is from the centre that limits transformation, because business must act in favour of the common good of society that is universally prescribed and ends in the good of business – profit. On the other hand, Jones’s aporetic CSR may end in a sterile acceptance of the status quo. The problem with these perspectives is that they ignore the fact that change does not occur because of agreement about the common good of society or the complexity of the present. Change is the result of the appearance of the other from the margin that challenges society as a whole. Thus, CSR is an act of justice because deconstruction does not lead to undecidability and relativism. Woermann (2013:109) states that “Derrida’s project – which focuses on different (better) ways of being – is at odds with the traditional way of doing business ethics (as exemplified by De George’s position), which is essentially a way of downplaying differences in the name of a common ethical experience, a common moral foundation”. Deconstruction contains a normative moment when the other appears as a function of justice. Thus, CSR is a critical immanent event that has the possibility of social transformation through the engagement with stakeholders who challenge the functioning and decisions of an organisation. The implication is that the subject and in the case of CSR, the corporation, is decentred, because society is decentred by the other. The corporation is organically part of society and an agent of justice when it recognises the face of the other. In other words, justice and social transformation are the centre of deconstruction in CSR. The practical implications of the deconstruction in CSR will be unpacked in the next section with reference to Royal Bafokeng Platinum.

5. Unpacking Deconstruction in CSR

The definition of CSR proposed in section four highlights four salient aspects, namely: immanence, criticism, engagement and transformation

5.1 Immanence of CSR

CSR is immanent and focuses on concrete situations and the complex social relations between different contexts. Deconstruction in CSR is suspicious of general models of CSR that focus on calculation and abstraction which bracket the impact of business on society. It deals with the complexity of the situation and the presence of outliers, randomness and the unexpected. However, it is also not consumed by complexity that can lead to undecidability. Thus, it suggests that not only is historical data relevant in stakeholder engagement, but that current information and events need to be added to make decisions (Woermann 2013:146-147). The focus shifts from accuracy and predictability to understanding stakeholder relations and society. It involves the ability to recognise stakeholders and the power relations that are present. The mistake to reduce an ethical dilemma to ordinary business is often made without realising that it is a problem with serious risks that cannot simply be rationally calculated. Traditionally, business will only engage certain more powerful stakeholders directly, while underestimating others like wage earning workers. Business may view some stakeholders as dispensable. Moriceau (2005:97) views this failure of recognition as the root cause of institutional CSR. However, it also does not engage to the point of malaise. It rather identifies social hierarchies and then acts constructively to transform oppressive situations. Therefore, deconstruction in CSR implies that this model has to be adjusted in terms of the circumstances that arise because power relations continually shift. In other words, stakeholder relations are dynamic because of the interrelationship between stakeholders and the appearance of the other.

5.2 CSR is critical

CSR is critical because the event is the point of departure. It does not negate the complexity of the situation with a general notion of the common good of society. It acknowledges that the interests of minority groups in society are crucial for social change and that laws need to be engaged and evaluated. Woermann (2013:108) notes that “…. the task of deconstruction is to challenge law in the name of justice and ethics”. Thus, justice is also linked to the moment because the law is never permanent, it is always a “partial and incomplete model of justice” (Woermann 2013:111). In other words, CSR is a critical practice that functions contextually and deals with particular situations, histories and social relations. This has the potential to challenge and change business as a function of social transformation (Paine 2000). It does not accept that the status quo is the only possible way for business and social responsibility to function. It accepts that any discourse or corporate structure is constructed with a particular aim and agenda. These aims and agendas of CSR need to be constantly re-evaluated because of social transformation from the margin.

5.3 Engagement in CSR

CSR is about engagement with stakeholders and the other. Engagement with the other is not directed at only the self-interest of business as a short-term project for maximising profit, it acknowledges the impact of business on society. In other words, engagement means that CSR cannot be reduced to abstract calculations to determine the benefits for business or malaise. On the contrary, CSR is a transformational activity that envisions the long-term sustainability of business in society through face-to-face engagement. Thus, engagement reflects an openness to the other that may transform the functioning and decisions of business and society because business is an integrated part of society. Irresponsible functioning and decisions of business relate to practices that exclude stakeholders and the other through oversight or business strategies that aim to exclude disruptive elements in society. This includes stakeholders who challenge the status quo e.g. societal interest groups. In other words, engagement highlights openness and the possibility of change. These are stakeholder not usually focussed on by CSR because of their low probability risk. However, they can have a high impact on social transformation and justice. Engagement is active and immanent and requires the patience to listen to the story of the other. It is not about calculation. It is personal and concerns human interaction, dignity and respect. Thus, engagement is about respect for the history, motivations, interests, emotions, fears and expectations of society.

5.4 CSR is transformational.

It affirms that the agents of change are not only individuals and governments. Business as a part of society can also be an agent of change. However, change does not come about through ideas related to the common good and laws. Change is a function of engagement with the other. Thus, change through engagement is transformational. It is a process that takes place over time. It requires continuous engagement. It is about the awareness of the preliminary nature of decision-making and the need for evaluation. The process is open-ended because life is open-ended. It affirms that mistakes can be made. Thus, even mistakes become part of the narrative of engagement with the opportunity to learn from the process.

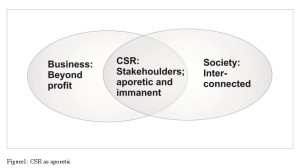

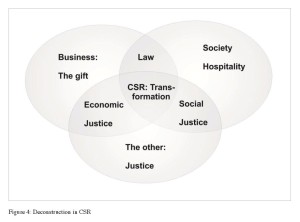

Figure 4: Deconstruction in CSR

5.5 A possible model of deconstruction in CSR

Although Jones refers to the fact that CSR is a perpetual state of deconstruction, this aspect is not developed as a means to highlight the role of the other as normative foundation for CSR. A closer reading of the deconstruction of the gift and the role of hospitality is helpful to develop a model of CSR and the role of deconstruction that goes beyond a mere state of aporia and undecidability. In the case of De George, the engagement of business and society remains limited to the function of business to employ members of society and make profit. CSR in this case can then be reduced to compliance to universal principles instituted in laws that govern society and protects citizens from abuse. Any business practice that makes profit through illegal means is irresponsible and unethical. Jones argues that this view of CSR does not take the aporetic nature of CSR into consideration. Laws are never final and universal principles remain under negotiation due to the challenges of contextual differences and the presence of stakeholders not being considered. The responsibility of business cannot be limited to profit and compliance to the law because interaction with stakeholders is always under negotiation and goes beyond the limitations of laws and regulations. In other words, society does not merely consist of functional units, but is dynamic because of the appearance of the other that is the nature of CSR. The problem is that this can be perceived as undecidable and lead to malaise with no transformation. However, according to Derrida, business has to be inherently hospitable to sustain the economic cycle. This expands the role of the other beyond a societal function. The other appears and transforms society and business. The other is not merely an aspect of society, according to Jones. The other is a function of justice and a normative aspect of the engagement of business and society.

5.6 Royal Bafokeng Platinum

The platinum industry and the formation of Royal Bafokeng Platinum[xvi] are a good examples of deconstruction in CSR:

In the 1924’s, Hans Merensky discovered the Merensky Reef in the Bushweld Igneous Complex – the world’s largest known deposit of platinum group metals (PGMs). Historically, this was a significant time in South Africa between the Natives Land Act of 1910 and the formation of the Republic of South Africa. The Natives Land Act led to ownership of land being transferred from the British to Afrikaners. This had direct implications for the Royal Bafokeng Nation (RBN), a community of approximately 300 000 Setswana-speaking people, whose land is situated on the Western Limb of the Bushveld Igneous Complex. The ‘platinum rush’ that ensued with Merensky’s discovery resulted in major mining companies stripping the RBN of their mineral wealth through the 20th century. The disempowerment of the RBN was within the legal parameter of apartheid policies and favoured mining companies. Legally, these companies functioned within the parameters of the law and the common good of society.

However, legal responsibility was based on a limited understanding of responsibility that excluded marginalised stakeholders or the other who were disposed of their land. These excluded voices became an increasing disruptive element in South Africa society and business. Although CSR was a foreign concept in the early parts of the 20th century, the deconstructive social forces were already present. Resistance to apartheid led to the transformation of South African society and business. This had a major impact on the mining activities of Anglo Platinum that mined the platinum that belonged to the RBN. The RBN laid claim to the wealth produced by these mines. This resulted in negotiations between Anglo Paltinum and the RBN. The result was that in 2002, the Royal Bafokeng Resources (RBR) was set up to manage the community’s mining interests. In 2004, Royal Bafokeng Finance (RBF) was established to develop a diversified non-mining asset base for the RBN. In this year, a 50/50 joint venture was entered into with Anglo Platinum with respect to the Bafokeng Rasimore Platinum Mine (BRPM). In 2006, RBR and RBF were merged to form the community-based investment company, Royal Bafokeng Holding (RBH). Continued stakeholder engagement between Anglo Platinum and RBH, that represented the financial interests of the community, led to the restructuring of 50/50 joint venture with Anglo Platinum in order to transfer control of BRPM to RBR. NewCo Platinum was established and incorporated as a subsidiary of RBH. NewCo was renamed RBPlat in June 2010. The BRPM JV restructuring transaction involved a change in the participation interests of the JV from that of joint control (50% RBR and 50% Rustenburg Platinum Mines, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Anglo Platinum) with Anglo Platinum as the operator, to RBR holding the majority interest (67% RBR and 33% RPM) and operating the JV operations. This transaction became effective on 7 December 2009.

The significance of this example is that the history of the RBPlat has led to a view of CSR that embraces social transformation to address colonial and apartheid injustices. Today in 2014, the significance of this process of deconstruction in CSR is bearing fruit. Since nearly the beginning 2014 workers of the three major platinum companies Anglo Platinum, Lonmin and Impala Platinum are striking for higher wages. This is one of the worst and most protracted strikes in the history of the platinum industry and many in the industry argue that it is the result of legacy issues linked to colonialism, apartheid and inequality in South Africa. Interestingly, since 2014 there has been no strike at RBPlat. What is clear is that the transformational engagement between AngloPlat and the RBN that went beyond traditional stakeholder engagement, led to a hospitable response to the legacy of colonialism and apartheid. Engagement with the RBN (the other) was therefore a response to the need for social transformation in the South African society. The implication is that this is transforming the community and is beneficial to the stability and profitability of RBPlat – the gift.

6. Conclusion

In this study it was argued that the CSR of Jones and De Georges represents an impasse in CSR because of the (im)possibility of foundations for CSR. This (im)possibility is addressed by the appearance of the other as a function of justice that highlights business as an agent of justice and transformation. Thus, deconstruction has a constructive dimension that transforms traditional CSR. This constructive dimension is the basis of an experimental model of deconstruction in CSR. Deconstruction in CSR is an interconnected and inclusive model that changes and adapts with the appearance of the other. Aspects of this model are clear in the case study of Royal Bafokeng Platinum in which case social transformation due to the legacy of colonialism and apartheid, resulted in a hospitable response from business.

NOTES

i. Mark Rathbone – Faculty of Economic & Management Sciences, School of Business Management, (Potchefstroom Campus), North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, mark.rathbone@nwu.ac.za

ii. The stakeholder CSR of Freeman (1984) must be distinguished from the shareholder CSR of Friedman (1992). Shareholder CSR highlights profitability as the main social responsibility of business. Stakeholder CSR identifies various stakeholders with which business need to interact like local communities, employees, environment, etc. In this regard, shareholders are just one of the stakeholders.

iii. The paper of Rendtorff is an attempt to deconstruct the tension between business as profit-making endeavour and business as philanthropy with the help of the philosophy of responsibility of Derrida (2008:1).

iv. Woermann (2013) is of the opinion that deconstruction helps CSR to become more honest by moving beyond reductionism associated with traditional ethics and CSR.

v. The word aporia was developed from the Greek aporia that means impasse, difficulty of passing, lack of resources, puzzlement. In the Platonic sense it is associated with the dialogues of Socrates that ends in puzzlement. For Aristotle it rather refers to a problem to be solved. In contemporary literature, it is closely linked to post-structuralism and Jacques Derrida who refers to the binary oppositions and paradoxes that are present in writing. These aporia need to be revealed in writing to discover the voice of the other or those aspects that are not central to the strategy of the text.

vi. Woermann (2013:98) notes that “De George’s position is indicative of traditional conceptions of CSR, and what is lacking in these conceptions is a critical reflection on (as opposed to merely a comparative account of) how our theories and embedded practices shape our views of morality and responsibility (as enacted in CSR)”.

vii. The limited focus on deconstruction in business ethics is discussed by Jones (2003:223-248) in the article “As if Business Ethics Were…Possible, ‘Within Such Limits…..”.

viii. Jones (2003:226-228) explores the implications of Levinas’ thought in the work of Derrida more fully in the article “As if Business Ethics Were Possible, ‘Within Such Limits”… (Jones 2003). “Levinas argues that, ‘before’ Being, one is always in a social world , always in relation with other people. So for Levinas the relation to the Other comes before Being, and hence Levinas posits the primacy of ethics over ontology, ethics being not simply a branch of philosophy but first philosophy”(Jones 2003:226)

ix. See Derrida’s discussion of Levinas in the The Gift of Death (1995)

x. This example is used by Jones, Parker and Ten Bos in For Business Ethics (2005) as case study of deconstruction in CSR (De George 2008:77).

xi. It is clear that the focus of deconstruction provides an alternative to the malaise associated with modernism. Taylor (2003:1-12), for example, identifies three dimensions of this malaise – individualism, instrumental reason and political apathy. Many regard individualism as the finest achievement of modern civilisation (Taylor 2003:2), but the right to choose and freedom from the “great chain of Being”, has a flip-side. It also leads to “disenchantment”, lack of purpose and lack of passion – “…the dark side of individualism is a centring on the self, which both flattens and narrows our lives, makes them poorer in meaning, and less concerned with others or society” (Taylor 2003:4). The fragmentation of individualism severs the organic interconnectedness of society and business. The part has to fulfil a function and is not able to contribute beyond that function in social transformation and justice. This has the negative effect of political apathy and business that can be become narcissistic.

xii. Woermann (2013:114) notes that, according to De George, “Derrida’s ethical relation is incompatible with the logic of organisations, defined as profit-making entities”.

xiii. Traditional CSR like the model of Schwartz and Carroll functions with clearly defined categories of economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic responsibilities that can reduce the importance of ethics as a “nice to have” (Woermann 2013:134).

xiv. Derrida (1982:213) states: “Metaphysics – the white mythology which resembles and reflects the culture of the West: the white man takes his own mythology, Indo-European mythology, his own logos, that is, the mythos of his idiom, for the universal form of what he must still wish to call Reason”.

xv. The notion of Heidegger of dasein (“being here”) is the foundation for reflection and meaning that is explored by structuralism (Melchert 2011:700-703). In other words, understanding is not linked to authorial intent or interests. Rather, understanding is dependent on the text that is present. This emphasises the linguistic and grammatical reality that is contained in the text. According to Derrida, this fixation on presence is part of the Western philosophical tradition going as far back as Plato – “…from Plato to Hegel (even including Leibniz) but also…from the pre-Socratic to Heidegger, always assigned the origin of truth in general to the logos: the history of truth, of the truth of truth, has always been…the debasement of writing, and its repression outside ‘full’ speech” (Derrida 1976:3). Derrida refers to this fixation as logocentrism or the immediate rational presence of truth in consciousness that is articulated in spoken words (Derrida 1972:xiv, 1976:11). In other words, writing is secondary because it is less trustworthy and more likely to be open to distorted interpretations. This is a fallacy because all reality is structured by language or texts. According to Derrida (1976:11), the priority given to speech is misleading because of the interdependence of speech and writing – speech is writing in oral form and vice versa. In other words, logocentrism disguises the violence of construction and reduction of reality. It serves power and ideology in the name of justice and liberty.

xvi. The information was obtained from the website of Royal Bafokeng Platinum http://www.bafokengplatinum.co.za/a/history.php.

References

Caputo, J.D. (1997). Deconstruction in a nutshell: A conversation with Jacques Derrida. New York: Fordham University Press.

Derrida, J. (1972). Dissemination. Trans. Barbara Johnson. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J. (1976). Of Grammatology. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak from De la Grammatologie (1967). Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.

Derrida, J. (1982). Margins of Philosophy. Translated by Alan Bass from Marges de la philosophie. Sussex: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J. (1991). Given time. Counterfeit Money. Translated by Peggy Kamuf. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J. (1995). Points: Interviews, 1974-94. Ed. Elisabeth Weber. Translated by Peggy Kamuf et al. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Derrida, J. (1995). The Gift of Death. Translated D. Wills. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

De George, R.T. (2008). An American perspective on corporate social responsibility and the tenuous relevance of Jacques Derrida, Business Ethics: A European Review, 17, 74-86.

De George, R.T. (2010). Business ethics. New York: Prentice Hall.

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston, MA: Pitman.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. In the New York Times Magazine 13 September 1970 (pp.32-33 and 122-126). New York.

Goosen, D. (2007). Die Nihilisme. Amsterdam: Uitgewery Praag.

Jones, C. (2003). As If Business Ethics Were Possible, ‘With Such Limits’…… Organization, 10(2):223-248.

Jones, C. (2007). Friedman with Derrida. Business and Society Review, 112:4, 511-532.

Jones, C., Parker, M., & Ten Bos, R. (2005). For Business Ethics. London: Routledge.

Melchert, N. (2011). Postmodernism and Physical Realims: Derrida, Rorty, Quine and Dennett. In The great conversation: a historical introduction to philosophy, 2(6):699-709. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moriceau, J. (2005). Faceless Figures: Is a socially responsible decision possible? In Maria Bonnafous-Boucher and Yvon Pesqueux (Eds.), Stakeholder Theory: A European perspective (pp. 97-100). Palgrave MacMillan. New York.

Paine, L.S. (2003). Is ethics good business. Challenge 46 2, 6-21.

Porter, M. & Kramer, R. (2006). Strategy and society. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review.

Rendtorff, J.D. (2008). Jacques Derrida and the deconstruction of the concept of corporate social responsibility. Paper presented at the conference: Derrida, Business ethics. Centre for Philosophy and political economy. University of Leicester, 14-16 May 2008.

Rossouw, D. (2008). Practising Applied Ethics with philosophical integrity: the case of Business Ethics. Business Ethics: A European Review, 17 2,161-170 .

Royal Bafokeng Platinum. http://www.bafokengplatinum.co.za/a/history.php

Sen, A. (1999). On Ethics & Economics. London: Blackwell.

Stoker, W. & Van der Merwe, W.L. (2012). Culture and Transcendence: A Typology of Transcendence, Leuven: Peeters.

Stone, C.D. (1992). The corporate social responsibility debate. In J. Olen &V. Barry (Eds.), Applying ethics (pp.442-443). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Taylor, C. (2003). The ethics of Authenticity. Harvard University Press. London: England.

Woermann, M. (2013). On the (Im)possibility of Business Ethics. Critical Complexity, Deconstruction, and Implications for Understanding the Ethics of Business. Springer. London.