ISSA Proceedings 2006 ~ On How To Get Beyond The Opening Stage

1. Introduction

What is the opening stage? And why would it be hard to get beyond it?

The opening stage – as many will know – is one of the four discussion stages contained in the familiar pragma-dialectical model of critical discussion (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1984, 1992, 2004), which constitutes a normative model for argumentative activities aimed at the resolution of a difference of opinion. It is one of the merits of this model that, in its description of the ideal argumentative process, it does not limit itself to argumentation in the proper, but narrow, sense of advancing arguments for a standpoint, but includes discussion stages where other necessary steps for the resolution of differences of opinion are located. Remember that there are just four stages, and that they are, in order, the following:

1. Confrontation Stage

2. Opening Stage

3. Argumentation stage

4. Concluding Stage.

Contrary to what may be expected, the opening stage does not figure as the first stage (whereas the concluding stage finds itself indeed neatly placed at the end). This is a vagary of nomenclature that sometimes breeds confusion even among experts. Apart from that, it is clear that the process of argumentation proper has been placed in the third stage, the argumentation stage, and that the first two stages figure as preparatory stages.

The problem I want to discuss actually pertains to both preparatory stages, namely: how can one get them completed, in a satisfactory way and within a reasonable time, to move on to what is properly called argumentation. However I will discuss this problem with special reference to the opening stage.

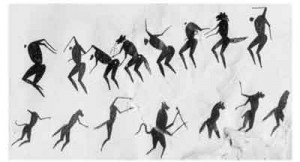

To enhance a more lively remembrance of the four stages of discussion you could picture them as a house with four rooms (see Figure 1).

To enhance a more lively remembrance of the four stages of discussion you could picture them as a house with four rooms (see Figure 1).

When guests enter into this house they start on the ground floor in Room 1, a kind of gym – a place suitable for boxing exercises – which represents the confrontation stage, i.e., the stage where a difference of opinion is made explicit. The goal is to get, ultimately, to Room 4, another ground floor room, giving on to the garden, where refreshments are served – drinks and tidbits – which room represents the concluding stage, i.e., the stage where agreements are achieved. Now to get there, our guests have to pass through two other rooms, both on the upper floor, which represent the opening stage (Room 2) and the argumentation stage (Room 3). In Room 3, the actual business of argumentation is going on: for instance, a standpoint S is being supported by argument. But before one gets there, a lot of preparatory work needs to be done. The agenda will be presented in the next section, but one thing that has to be settled is the choice of a system of discussion rules that the parties are going to adhere to. No wonder Room 2 is packed with theorists of argumentation debating these rules. The complexity of issues and the multiplicity of perspectives is making one wonder whether any agreement will ever be reached at all. One would be fortunate to see the people in Room 2 manage to come to an agreement about just the shape of their table. Even that issue can be nasty, as was the case at the opening stage of the Paris Peace Conference about Vietnam. As some will remember, in 1968-69 the shape of the table was debated for months. This, of course, was a case of opening a negotiation dialogue, not a persuasion dialogue or argumentative discussion. Yet, the case of the Paris Peace Conference constitutes a classical illustration of how difficult it may be to get beyond the opening stage of a discussion. (Which is not to say that the issue of the shape of the table was unimportant at the time.)

The rest of this paper will be organized as follows. As I announced before, I shall first present the agenda for Room 2, i.e., a task list for the opening stage, assembled from pragma-dialectic writings (Section 2). Then I shall illustrate these tasks in a dialogue (Section 3), point out some problems (Section 4) and start on some sketch of a way to adapt the architecture of critical discussion in order to overcome these problems (Section 5).

2. The Agenda

Coming from downstairs (the gym) with a freshly formulated difference of opinion our guests must now, in Room 2, consider what they will do about their dispute. Fortunately there is, put up on the wall, a large piece of paper on which their tasks are listed. They must come to agreements on the following issues:

1. whether to opt for discussion, i.e., whether to engage in some kind of discussion at all, or rather do something else, for instance, draw lots or have recourse to violence (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1984, pp. 85, 88, 105; 1992, p. 35; 2004, pp. 68, 137);

2. whether to opt for argumentative discussion ( persuasion dialogue), which is aiming at rational conviction (rather than, for instance, negotiation dialogue aiming at a compromise or an eristic altercation;[i]

3. what global discussion rules to use to organize the discussion, i.e. what system of persuasion dialogue to adopt (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1984, pp. 88, 105; 1992, pp. 35, 39; 2004, pp. 60, 68, 137, 142-43);

4. who will perform the role of Protagonist and who will perform the role of Antagonist, with respect to each of the propositions constituting the difference of opinion (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1984, pp. 85, 88, 105; 1992, p. 35, 39; 2004, pp. 60, 105, 137, 141-42);

5a. what logic system is to determine the underlying concepts of validity and consistency (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, p. 94; 2004, p. 148);

5b. what procedures to adopt for testing for validity and consistency in concrete cases that may arise at the argumentation stage (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004, p. 148);

6a. what argument schemes to admit and to what standards applications of these schemes should conform in order to be correct (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, p. 159; 2004, p. 149);

6b. what procedures to adopt for testing for admissibility and correctness of application of argument schemes in concrete cases that may arise at the argumentation stage (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, p. 158-59; 2004, p. 149-50);

7a. what propositions to accept as basic premises, whether as axioms or as defeasible presumptions, to function as starting points for arguments (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, p. 35, 149, 151; 2004, p. 60, 68, 137, 145);

7b. what procedures to adopt for testing for acceptability of basic premises in concrete cases that may arise at the argumentation stage (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004, p. 145-48).

A glance at this paper on the wall should convince the participants that they need not fear to run out of work, unless they would skip, or only summarily discuss, large parts of the agenda. The dialogue in the next section will serve as an illustration.

3. A Dialogue

In their conversation, as recorded below, Ophelia and her father will demonstrate the various tasks that need to be performed to complete an ideal opening stage. Numbers in brackets indicate the various items on the agenda.

Polonius: To say it just simply and in unadorned language: dolphins are astoundingly intelligent.

Ophelia: Why do you say so, father?

Polonius: Oh dear, didn’t you see the latest issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science?

Ophelia: Stop, daddy. If this is an argument, you are skipping the opening stage.

Polonius: Am I?

Ophelia: Yes, before you can present an argument we must first agree what to do about our difference of opinion. [1] Shall we discuss it?

Polonius: By all means.

Ophelia: [2] Contentiously? Or by rational persuasion?

Polonius: Rational persuasion would be perfect, sweetheart. Someone will try to convince the other that dolphins are really smart.

Ophelia: And someone else will try to cast doubt on that proposition. [3] What discussion rules shall we use? How about the pragma-dialectic model?

Polonius: Fine. [4] Let me be the Protagonist.

Ophelia: And I shall be the Antagonist. [5a] I suggest we use classical propositional logic.

Polonius: [5b] And we’ll check specific cases by truth tables. [6a] I suppose arguments from authority will be acceptable?

Ophelia: I do not fancy them. But OK, provided the authority is impeccable.

Polonius: [6b] Scientific journals would count as such?

Ophelia: And the bible.

Polonius: [7a] Now, what propositions do we agree about to begin with? I presume that if a species uses proper names they must be astoundingly intelligent?

Ophelia Absolutely! But only humans do.

Polonius: Ho stop! We are not yet through with the opening stage.

Ophelia: What more?

Polonius: [7b] As a general procedure to agree on basic premises, I suppose you will gladly accept Freeman’s manual (2005) in its entirety?

Ophelia: With pleasure. But now let’s have our argument.

It is obvious that in this conversation between Ophelia and Polonius the opening stage was cut down so as to retain just the barest exchange needed to address each item on the agenda. (Nevertheless what was said sufficed to give Polonius a very strong position as a Protagonist in the next room.) It is not hard to imagine that a more serious opening stage would have to be much more involved and protracted.

4. Problems

The most striking problem about the opening stage is its tremendous workload. Given that it is at that stage unknown what arguments will turn up in the next room, how can one make sure that enough argument schemes, procedural methods, and substantive propositions have been agreed on to have a fruitful argumentation stage? When is an opening stage completed? This I shall call the completion problem.

The completion problem becomes even more pressing on three counts. First there is the indefinitely long list of propositions to be screened for eligibility as basic premises. Perhaps this list can be handled more systematically and more efficiently by agreeing on procedures to establish basic premises instead of considering them one by one. Even so the discussants need to consider, section by section the issues in Freeman’s book (2005).

Second, what if the discussants do not immediately agree on a proposed basic premise, or on the appropriateness of a type of argument, or its conditions of correctness, or on some matter of logical theory, or on some detail of one of the testing procedures? How do they settle their differences? If they decide to resolve them by critical discussion, this would lead to yet another opening stage to prepare for the argumentation stage of this inserted discussion. And if differences of opinion were again to arise in the opening stage of this inserted discussion, this could lead to yet another inserted discussion, and so on. Thus, the danger of an infinite regress looms ahead.

Third, even when both parties agree after some time that their discussions at the opening stage now provide a sufficient basis for them to proceed to the next room, they could, at the argumentation stage, run into unforeseen problems that necessitate a return to the opening stage. According to Van Eemeren and Grootendorst, as soon as the Antagonist overtly doubts some explicit or implicit premise used by the Protagonist, a new difference of opinion (a subdispute) arises occasioning a new discussion (a subdiscussion):

Besides advancing contra-argumentation against all or part of his opponent’s argumentation, a discussant can also indicate that he does not accept all or part of it. This he does by casting doubt on the statement or statements concerned or by describing them as insufficient justification or refutation. In all these cases this means that strictly speaking a new dispute has arisen which in turn gives rise to a new discussion, the outcome of which may, however, be crucial to the resolution of the original dispute. (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1984, p. 89, original emphasis)

Applying the pragma-dialectical model of critical discussion to this new discussion (the subdiscussion), one must conclude that, upon entering a subdiscussion, another opening stage is called for. Since the opening stage of the original discussion may be so construed as to include the opening stages of the subdiscussions, one may also express this by saying that a return to the opening stage of the original discussion is required. For instance, a return to the opening stage would be required if Polonius, in the argumentation stage, were to present an argument that is thereupon criticized by Ophelia. (The example continues the dialogue recorded above at the point where the discussants enter the argumentation stage.)

Polonius: Dolphins are astoundingly intelligent, because they are a species that uses proper names and if a species uses proper names they must be astoundingly intelligent.

Ophelia: But how do you know they use proper names?

Polonius: That was in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.[ii]

Ophelia: Ho stop, daddy. Mine was an expression of doubt, so we are having a subdispute and must first return to the opening stage.

Van Eemeren and Grootendorst suggest that for subdiscussions one could do with the blanket stipulation that they must be “conducted in accordance with the same premises and the same discussion rules accepted in the original discussion” (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004, p. 147). But it seems hard to exclude the possibility that the special character of some premise would require some special provisions as to the way it should be defended. For instance, the original discussion may be about some moral proposition, and not require a deductive proof, whereas one of the premises used by the Protagonist may belong to applied mathematics. If so, upon each utterance of doubt, expressing a difference of opinion, a return to the opening stage would have to follow, a circumstance that would aggravate the problem of getting beyond the opening stage.

There is, however, also a reverse problem, which arises if the parties would indeed succeed in bringing their opening stage to definite completion. This is the fixity problem, the problem that, once the opening stage has been completed, hardly anything is left for the argumentation stage. The decisions taken at the opening stage seem to suffice to determine completely the formal and informal logic that governs the argumentation stage as well as the set of available basic premises. Thus it seems to be determined whether or no an acceptable argument for the initial standpoint can be put forward. Hence the opening stage all but determines the outcome of the argumentation stage, all interesting matters having been discussed at the earlier stage. Given that the argumentation stage is usually seen as the heart of the argumentative process, this is at least an odd result.

A more technical and theoretical problem is that of the relation between the concepts of metadialogue and that of an opening stage. This is the status problem: does the opening stage belong to metadialogue? In a former paper I used the opening stage as an example of metadialogue (Krabbe 2003) because it contains dialogue about dialogue. But within pragma-dialectical theory the opening stage is clearly positioned as one of the stages of the ground level dialogue. This needs to be sorted out.

5. Solutions

At this point I would be glad to conclude my paper since, as usual, I see many problems but hardly any solutions. Nevertheless I shall present some suggestions to steer between the Scylla of the completion problem and the Charybdis of the fixity problem. The goal is of course to get a more realistic, yet normatively strict, set of rules for dialectic.

Foremost, I think it would be a good idea not to try to treat all tasks on the agenda of the opening stage on an equal footing. These tasks may be relocated at different points of the dialectic procedure.

As far as I see there are four possible locations for these tasks:

1. outside the discussion;

2. at the opening stage of the discussion;

3. in a metadialogue embedded in the discussion;

4. at the argumentation stage of the discussion.

The first location lies outside the dialectic process. The idea is to remove some tasks from the dialectic procedure and to presuppose that these tasks were performed before the discussion starts. This way of removing items from the agenda could be considered for

(1) the decision whether to engage in discussion at all and

(2) the decision to engage in persuasion dialogue and

(3) the decision to engage in a specific type of persuasion dialogue which is characterized by a specific set of discussion rules. The task of the dialectician is just to describe a certain system of discussion rules and does not include the description of rules that govern the decision to select the very system he describes.

The second location coincides with the present location of these tasks at the opening stage as a preparatory stage of the dialectic process. The following tasks on the agenda could keep their place at this stage: (4) the decision who is to perform what role; (5a) the decision on logical theory and (6a) the decision on appropriate argument schemes including some of the theory of correct application of these schemes; for the other items, which concern procedures ((5b), (6b), and (7b)) or propositions ((7a), and (7b) again) it could be made optional to what extent they are to be discussed at the opening stage.

The third option for locating tasks on the agenda would be to execute them in a metadialogue, which in a sense amounts to returning to the opening stage. This metadialogue must however be embedded in the argumentation stage, i.e., at the point where the participants enter the metadialogue, it must be functionally relevant for the purpose of that stage. This option is suitable for discussing details of the procedures that take care of (5b) the application of logic, of (6b) the application of argumentation schemes, and of (7b) the testing for acceptability of basic premises. Consequently, these matters will be discussed only when, at the argumentation stage, the occasion arises to do so. Metadialogue can also be used for (7a) the determination of the status of proposed basic premises.

The fourth location is the ground level discussion itself. It is another suitable location for (7a) the introduction of basic premises, supposing that the Antagonist is free to concede propositions that may be used as basic premises in addition to those granted at the opening stage.

The reorganization of the agenda of the opening state may not, in all respects, provide a solution for the completion problem, but it will at least mitigate the trouble. For if such a reorganization is accepted, one forgoes the ambition to achieve completion of the original agenda at the opening stage. Even for the part of the agenda that remains at the opening stage completion is not necessary, since there is lots of room to make repairs later in the metadialogues.

But how about the danger of an infinite regress? To avoid an infinite regress in the opening stage, it suffices to stipulate that the opening stage, in its reduced form, should not itself exhibit argumentative discussion but rather be limited to some uncomplicated version of negotiation dialogue.[iii] However, a theoretical regress in the metadialogues cannot be ruled out in this way, since, presumably, these must be argumentative. In this case, however, infinite regress can be condoned as an acceptable idealization. Moreover, infinite regress will not occur in practice, since, as we know, real discussions are all finite in length.

About the other two problems I shall be brief. Upon reorganizing the agenda, the fixity problem disappears now that more of the tasks are left to the argumentation stage. As to the status problem: we see that not all of the tasks of the original opening stage need to be performed at a metadialogical level, though some will. So part of what used to be the opening stage will retain the status of ground level discussion, and part will be reassigned to the metalevel.

NOTES

i. In the pragma-dialectical writings this item and the preceding one occur as one issue of deciding to discuss.

ii. May 2006.

iii. I am thinking of a simple system of offering, accepting, and rejecting, without recursion, and without embeddings of dialogues of other types.

References

Eemeren, F. H. van & R. Grootendorst (1984). Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussions: A Theoretical Model for the Analysis of Discussions Directed Towards Solving Conflicts of Opinion. Dordrecht/Cinnaminson, NJ: Foris.

Eemeren, F. H. van & R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies: A Pragma-Dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale, NJ, etc.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F. H. van & R. Grootendorst (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, J. B. (2005). Acceptable Premises: An Epistemic Approach to an Informal Logic Problem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krabbe, Erik C. W. (2003). Metadialogues. In: Frans H. van Eemeren, J. Anthony Blair, Charles A. Willard, and A. Francisca Snoeck Henkemans (Eds.), Anyone Who has a View: Theoretical Contributions to the Study of argumentation (pp. 83-90, Ch 7), Dordrecht, etc.: Kluwer.