Chapter 3: The Views of Investors ~ Irish Investment In China. Setting New Patterns

Introduction

Introduction

As indicated above, traditional Irish outward FDI to the US and Europe is disproportionately horizontal in nature and is concentrated in the non-traded sector. (Barry et al, 2003) This chapter explores the views of business executives as to the rationale underlying their investment in China, their experience since investing, the disincentives and barriers to investing in China, and the role which executives see for state support in ameliorating the locational disadvantages which China poses.

By analysing the organisation and scope of activities of Irish MNEs which have invested in China, conclusions can be drawn as to whether Barry et al’s model is applicable to Irish FDI into China. The experiences of executives in both the Irish and non-Irish MNEs categories allow us to draw conclusions as to the locational challenges which China may pose. These perceptions and an analysis of the investment climate in the next chapter will permit conclusions to be drawn as to whether the validity of our sub-hypothesis holds, namely that the Chinese investment climate is considerably different from that faced by Irish investors in developed economies, the traditional location for outward FDI.

Should significant locational disadvantages be found to exist, within the meaning of Dunning’s eclectic paradigm, our prescriptive research question will examine the potential role which exists for government to assist potential investors.

This chapter sets out the results of the research undertaken for this study. Initially, the profiles of the investing companies (both Irish and non-Irish) will be set out, but in a manner which respects the confidentiality offered to interviewees. This will be followed by a consideration of the investment rationale and the available incentives, which drove the MNE to invest in China. Using this framework, the locational advantage which China offers can be identified.

Locational disadvantages will also be explored by examining the experience of executives since investing. The manner in which MNEs protect their ownership advantage through utilising internalisation advantage will offer guidance to potential Irish investors. Perceptions on the role of the state will be explored, which will assist in the consideration of our prescriptive research question. This will be followed by an evaluation of the views of Irish MNEs which have invested in Eastern Europe. It will be interesting to note if their perceptions as to the challenges facing investors in China will be borne out by the view of both Irish and non-Irish MNEs which have already invested in China.

Profile of the MNEs included in this Research – Irish MNEs

There is a significant variation in the size and scope of the Irish MNEs which have invested in China. The average size of the MNE’s investment in China was € 168 million. However, this figure is skewed by one large investment greater than €1 billion. When this investment is excluded, the average investment of Irish MNEs was € 6.3 million, which represents a significant commitment on the part of the parent Irish firm. The average number of employees in the Chinese subsidiary of Irish MNEs was 332. Again, this is distorted by the size of one MNE. Excluding this MNE, the average was 49 employees. This is not a large number of employees by Chinese standards. Perhaps this small number can be accounted for by the fact that just under half of the subsidiaries are in the hi-tech sector, where employee productivity tends to be high, and another is in the property sector, but not directly engaged in construction projects. LOCOmonitor (2006) found that the average number of employees in the overseas subsidiaries of Irish MNEs is 147. Taking all Irish investments in China, the number of employees is higher than the global average.

Turning to the parent Irish MNE, globally Irish MNEs which have invested in China had an average annual turnover of € 1.4 billion. Again there are large divergences within this average figure. The average number of employees globally was 4,247. This data gives an indication of the size and diversity of the MNEs which were included in this research.

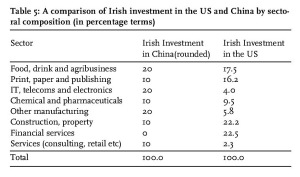

Having analysed the activities of the Chinese subsidiaries we can say that, of the Irish MNEs which have invested in China, just over 80% are in the traded sector. The proportion between vertical and horizontal FDI is broadly equal. These results have significant implications for this research and indicate that Barry et al’s model is not directly applicable for the current wave of Irish investment in China, as it is largely in the traded sector and could not be described as disproportionately horizontal. We shall return to these findings in chapter five, when the nature of Irish FDI into China is explored.

Non-Irish MNEs

Among the non-Irish MNEs included in this study, the average investment was € 520 million, compared with the average Irish investment of € 168 million.

The average turnover of the Chinese subsidiary of the non-Irish MNE was € 210 million and the average number of employees in China was 4,047. Globally these MNEs had an average turnover of € 68.6 billion. The average number employed globally is 114,000. While the scale of these MNEs and their Chinese subsidiaries is larger than that of the Irish MNEs and their subsidiaries, the non-Irish MNEs were selected with reference to the Government’s Asia Strategy. In addition, the interviewees selected were involved in the initial decision to invest in China and have considerable experience of the investment climate in China.

Analysing the activities of these subsidiaries, it can be said that all of the investments were horizontal in nature and that 75% operate in the traded sector. While the breakdown in the traded/non-traded sector is not very different from that of the Irish MNEs, the FDI of the non-Irish MNE population is totally horizontal. This finding should not be given undue weight as it would be possible to assemble a cohort of MNEs which replicates the Irish MNEs. Based on this research, and accepting the limited size of the population, there would appear to be a stronger level of FDI in the traded sector. This is possibly a reflection of the dominance of manufacturing in the Chinese industrial base. However, this is changing along the eastern seaboard with the service sector increasing in market share. We shall return to this topic later.

An interesting comparison of the ratio of turnover and staffing of the Chinese subsidiary as compared with the global operation shows a divergence between the Irish and non-Irish MNEs. Of the Irish MNEs, the average turnover of the Chinese subsidiary as a percentage of global turnover was 46%. The average employment was 40%. However, in the case of the non-Irish MNEs the turnover of the Chinese subsidiary as a percentage of global turnover was 14%. The corresponding data for employment was 4%. Presumably this is a reflection of the truly international nature of the non-Irish MNEs and conversely, the limited international operations of Irish MNEs, with the Chinese subsidiary playing a significant role in the corporate structure of the Irish MNEs. It also points to the increasing number of medium-sized Irish companies which are investing overseas. This supports the view of Moosa (2002) who, in discussing the strong rebound which took place in international FDI after the slowdown in 1990-92 associated with the East Asian financial crisis, points to the growing role of smaller firms engaging in outward FDI.

Structure of the Chinese Subsidiaries – Irish MNEs

Among the Irish MNEs, just under 20% are in joint venture arrangements and just over 80% are Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprises (WFOEs). The joint venture MNEs decided to enter into this form of arrangement as it was perceived as the easiest manner in which to enter the particular markets in which they are active. In one case the MNE established a relationship with a Chinese partner firm which is in a position to obtain the required licence. (At the time of entry only domestic firms could be licensed. While this restriction has now been lifted, de facto it still proves difficult to obtain such a license.)

Most executives were opposed to the concept of a joint venture structure. They cited the risk of the loss of intellectual property rights (IPR) as a reason for not entering into a joint venture, fearing that their technology would be leaked to competitors. One executive commented that he ‘would not be happy to go in with any third party given the hi-tech risk we would face’. The consulting company executive observed that virtually all new investments in China are Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprises with a marked reluctance to enter into Joint Venture arrangements. He sees the lack of accountability within a Joint Venture, particularly on the Chinese side, as one of the main weaknesses of this form of market entry. In addition, he described a Joint Venture as a particularly bad way of protecting intellectual property.

Among the Irish investments all but one were greenfield investments. However, most Irish outward FDI uses M&A activity as an entry strategy (O’Toole, 2007). When this issue was raised during interviews, one executive replied that ‘the challenges associated with due diligence is not something we wanted to do’. ‘Even in Ireland, before entering into a joint venture you would conduct a lot of research and due diligence investigation on a prospective partner, and in China that’s even more important’. (Enterprise Ireland, 2005: 17) Cantwell and Santangelo (2002) argue that merger and acquisition activity is at a considerably lower level in Asia than in other regions. The gain in market power is greater if an investment takes the form of a merger or acquisition as it directly eliminates one potential rival. The threat which a joint venture arrangement poses to the protection of intellectual property rights can be considered as a locational disadvantage which threatens the MNE’s ownership advantage. Lieberthal and Lieberthal (2004) argue that joint ventures are particularly difficult in China because of diverging objectives between the two partners. While most MNEs want to reinvest profits to increase market penetration, Chinese firms, which are typically cash-strapped, want to extract profits.

Non-Irish MNEs

Almost 90% of the non-Irish MNEs are Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprises (WFOE). One of the executives recalled the experience of joint venture arrangements which the MNE had previously had:

In terms of ownership structure, we started life in China as a joint venture. At one stage we had over ten joint ventures and only two years ago did we manage to bring all their operations into a single WFOE. In a JV (Joint Venture) too much energy is spent meeting the needs of the JV partner rather than concentrating on core business objectives.

A financial services executive pointed out that foreign banks are reluctant to purchase 20% or more of any Chinese financial institution. If the bank does so, the Chinese subsidiary would be subject to prudential supervision by the financial regulator in the bank’s home economy.

One of the non-Irish MNEs operates in the education sector. While it does not have a joint venture arrangement, it has a Chinese partner with a minority shareholding. This is not unusual in this sector, as education is tightly regulated by the authorities. We shall return to this issue in chapter five, as education is one of the sectors identified in the Government’s Asia Strategy as offering the potential for deepening economic ties with Asia.

A view among the executives interviewed is that control is important when making an investment in China. This supports the view of Moosa (2002), who states that control is a distinguishing feature of FDI as compared with other forms of investment. It can be deduced from the response of interviewees that a joint venture company structure is a locational disadvantage within the meaning of Dunning’s eclectic paradigm. A wholly foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE) represents an internalisation advantage. There is the additional risk that a joint venture arrangement may lead to a leakage of intellectual property. Should this occur, the MNE’s ownership advantage would be dissipated. Accordingly, when investors are considering the appropriate organisational structure to adopt for their Chinese subsidiaries, they should seek to retain internalisation advantage by utilising a WFOE structure and thereby avoid threats to ownership advantage.

Rationale for Investing and Incentives

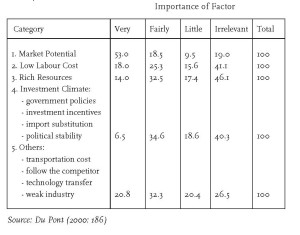

An examination of why MNEs invest in China is of assistance in identifying the locational advantage which China offers.

Irish MNEs

Of the Irish MNEs, over 80% decided to invest in China because of the market potential which is on offer, 10% invested because of the locational advantage which China offers in labour costs, and just under 10% invested for both market opportunity and labour cost considerations, with a slight preference for the latter. It can be said that within Chen and Ku’s (2000) categorisation, the vast majority invested for expansionary purposes.

The principal benefit identified by virtually all investors is the market opportunity which China presents. These MNEs see the emerging market in China as the natural progression to their existing activities. They recognise the emergence of the middle class in China, which has increasing amounts of disposable income to spend on consumer products. In addition, they see investing in China as adding value to their global operations. O’Toole (2007: 394) argues that ‘most of the FDI from Ireland is motivated by gaining access to overseas markets’. This research corroborates this view and shows that Irish FDI into China conforms to this general pattern.

In some cases MNEs are following companies with which they already have a close business relationship and who have already invested in China. One executive stated: ‘Some of the large US multinational companies which we supply were moving their operations to China. This factor made the decision to invest easier as there was a need to follow our market’. This view is corroborated by a non-Irish MNE executive who pointed out that all of their suppliers have established a production facility in China in order to maintain their supply contracts. An interesting observation made by an Irish MNE executive in the hi-tech sector was: ‘Not all our international competitors were operating in China. Therefore, we knew we would not face the same level of competition as we do in the USA. In addition, there were no Chinese competitors in the specialised hi-tech area in which our firm specialises’. Another executive argued that in the electronics industry ’you have to be in China, simply because all the suppliers are here. Time-to-market is crucial to gaining contracts. Because all the components are made here, we had no choice. Nowhere else has the capacity’. An executive of a chemical MNE commented that ‘the attraction of China is its very large market. While the technology they use is very different to ours, Chinese producers can produce at lower cost. We can’t afford to be outside the market. To sell within, we will use our production facility as a bridgehead’.

A packaging executive spoke of a new market emerging for foreign investors within China – ‘Chinese companies want to sell products in Europe and the States; to do that, they need European standards. That’s where we come in’. Food sector MNEs have decided to focus on the business-to-business sector rather than attempt to penetrate the retail sector which is viewed as:

…too complex for foreign companies to break into. Maybe we will look at it in ten years time. A strategic decision has been taken to focus on the business-tobusiness market rather than the retail sector. The retail sector is really complex for foreign companies, given the distance from the home economy and the branding challenges which would require a significant outlay on advertising.

Worthy of note is the additional opportunity which one MNE has identified. It intends servicing its market on the west coast of the USA from China rather than from Europe, which it currently does, as the costs involved are considerably lower.

There was a clear perception that the immediate market potential is along China’s eastern seaboard. Establishing an operation in the centre or west of the country was described by one executive as ‘challenging, mainly because of the undeveloped logistics system.’

One MNE invested with a dual objective. Firstly, it wished to exploit the market opportunity for its existing products. Secondly, it wanted to use its plant in China to manufacture components for its global supply chain as a means of reducing costs.

Only in the case of one Irish MNE is the relatively low cost of labour the prime motivator. Buckley (1989) argues that location advantage enables MNEs to gain maximum advantage from differential prices of non-tradables in particular locations, particularly labour costs.

The dominant objective of exploiting market opportunity among Irish MNEs is in contrast to the perception that investors are attracted to China because of cheap labour. This finding supports the views of Li and Li (1999), who argue that investors from developed economies are likely to be attracted by market opportunity rather than low-cost labour. These findings are also in line with Van Den Bulcke et al’s (2003: 58) analysis of EU investment in China, which is that ‘they [EU investments] are relatively more concentrated in capital and technology intensive sectors, have a large investment size and a high localmarket orientation’.

Non-Irish MNEs

All of the non-Irish MNEs included in this research invested in China in order to exploit market opportunity. However, two identified low labour costs as a factor contributing to this decision, but stressed that market opportunity was the primary motivation. The consumer products executive stated that ‘we decided to invest simply because of the size of the potential consumer market – 1.3 billion consumers’. Another executive expanded on the market opportunity which the MNE had identified: ‘China is a natural extension of our geographic business; there was a need to “follow our customers” as we are heavily involved in funding the exploitation and acquisition of natural resources’. The executive of another MNE mentioned that most of the firm’s suppliers have now located a manufacturing facility in China, which provides easier access to materials. This point is of interest to potential Irish investors who provide services and goods to other multinationals.

One MNE executive pointed out how important market opportunity is by indicating that labour costs played no role in the firm’s decision: ’We decided to invest in China solely because of the potential market. The cost structure of our firm is not typical; materials account for 50-60% of total cost and labour costs are typically in the region of 10%, so cheap labour didn’t bring us here’.

Reflecting the dual objectives of another MNE, the respondent stated: ‘We invested because we saw the market coming. But also to have a lower cost production base, not only for China, but also in south-east Asia. We can produce heaper in south-east Asia, but we can get good quality production cheaper in China than in Europe’.

The evidence presented above by the majority of interviewees, in the case of both Irish and non-Irish MNEs, points clearly to the locational advantage of the market opportunity which China offers. Building on the ownership and internalisation advantages which these MNEs possess, investors recognise the market opportunities which China offers, and wish to exploit it. Interviewees acknowledged that this market opportunity currently exists only along the eastern seaboard. This represents an important regional variation and modifies the locational advantage which China offers. Accordingly, it can be said that the locational advantage currently exists only in one segment of the Chinese market and not throughout the country.

Incentives

The level of incentives offered by the Chinese authorities did not feature prominently as a motivation for investing, among either Irish or non-Irish MNEs. As the majority of those interviewed cited market opportunity as their motivation for investing, this is not surprising. This view supports a finding in Agarwal’s (1980) study, which shows that incentives have a limited effect on the level of FDI, as investors base their decision on risk and return considerations.

MNEs in the hi-tech sector spoke of attractive packages which are offered by local government authorities. One executive stated: ‘As we are in the hi-tech sector, we were in discussions with the authorities in several locations to negotiate the best possible package’. The interviewee from the consultancy firm suggested that during the set-up stage, local authorities have considerable latitude when negotiating, with large investors who obviously possess the leverage to obtain a more favourable deal. He recommended that companies should establish their operations in a Special Economic Zone in order to gain the most advantageous tax and incentive packages.

Interviewees spoke of the various incentives available from local governments. One executive recalled how the MNE received considerable grant assistance when constructing its headquarters building. As it is a prestigious MNE, local governments competed strongly to attract the FDI to their particular regions. As a result of the generous land-use rights offered, the MNE effectively built its corporate headquarters at little or no cost. This points to a regional variation which investors should take into consideration when making an investment decision. As such, it can represent a locational advantage or disadvantage. We shall explore this further below.

The clear view of interviewees is that taxation played a role only in the choice of location within China and not in the decision to invest itself. One executive stated: ‘while the tax arrangements are good, this is not why we invested. They help the bottom line, but even without them we would be here. The moves to increase corporation tax for foreign entities will not force us to change our strategy’.[i]

As discussed above, the literature on the effect of taxation on FDI offers diverging opinions. The result of this research confirms the view held by Moosa (2002) that it is the overall environment of a particular country which attracts inward FDI and the expected return on capital invested. In the case of MNEs which invest in China for market opportunity purposes, we can say that the relationship between taxation policies and FDI is not particularly strong for this category of investors.

While the following sections will explore locational disadvantages, it should be borne in mind that China continues to offer strong and very positive locational advantages.

This almost goes without saying, given the strong levels of inward FDI which China continues to enjoy. The purpose of exploring locational disadvantages is firstly to assess their impact and secondly to explore whether or not it is appropriate for state intervention to ameliorate such locational disadvantages.

The first section, entitled ‘Experience Since Investing’ will explore the responses of executives to the questions relating to experience of the set-up stage, regulatory issues and transfer of technology. The responses identified in these areas can be considered to be minor locational disadvantages and offer an indication of the business environment facing investors. These challenges are not unique to China and could be experienced in other investment locations, in both developed and developing economies. As such, they can be considered to be in the realm of general locational disadvantages which investors face when establishing a subsidiary abroad. As set out above, the reality is that foreign companies will incur some additional costs in comparison with indigenous companies. These extra costs range from a culturally unfamiliar environment to legal and political uncertainties.

In the section entitled ‘Disincentives and Barriers to investing in China’, particular disadvantages and barriers to investment will be discussed.

Experience Since Investing – Irish MNEs

Executives of Irish MNEs spoke of the importance and challenge of obtaining appropriate business licenses. The executive of one hi-tech MNE commented that ‘Not only do we need a business licence, we need a licence for each product we manufacture and an import licence as well’. This points to a complex regulatory regime. It also indicates the unfamiliarity of Irish MNEs with the requirement of obtaining business licences, which is not a practice in Ireland.

Some specific issues were highlighted. The service sector MNE pointed to the difficulty of operating in a restricted sector. While this sector has recently been opened up to international investors, in line with China’s WTO commitments, the executive is reluctant to apply for a licence, as the one foreign firm which has done so has experienced enhanced regulatory surveillance in the conduct of its business.

One executive offered an example of the level of bureaucracy which Irish MNEs would not be accustomed to – ’If there is a discrepancy between the amount of raw materials bought by the company versus the amount of goods estimated to be made from that amount, the customs will halt the shipment until the discrepancy is cleared up’. While the purpose of this approach is to prevent the loss of fiscal revenue, it presents a challenge which MNEs operating in the West would be unaccustomed to.

One of the food sector executives complained of a lack of national treatment:

‘Food ingredient importation is particularly restrictive with Chinese companies not subject to the same level of rigour and inspection. This is a form of non-tariff barrier and one which merits government intervention’.

A consistent challenge identified by executives is the difficulty of locating and recruiting suitably qualified staff. ‘One of the main obstacles experienced by our firm is the ability to attract management who are competent and can integrate into the firm’s culture’. Lack of managerial expertise was also identified as an on-going difficulty. This view is corroborated by the OECD (2000).

Another executive was of the opinion that the ‘biggest difficulty during our set-up phase was identifying and employing a suitable country manager. We only located someone through the help of Enterprise Ireland’. An executive in a firm for which delivery times are critical stated that the firm ‘couldn’t afford to lose staff, so at an early stage I decided to pay 15% above the going rate’.

Non-Irish MNEs

Executives of non-Irish MNEs were less pre-occupied with the business licence issue than were Irish investors. Most executives were of the opinion that if the paperwork was in order, the licences could be obtained in a relatively straight-forward manner. One executive stated that when he worked in Germany, licences could take longer to obtain. This difference between the perceptions of Irish and non-Irish investors may be accounted for by the fact that industry may be more regulated in continental Europe than in Ireland, with permits and licences required to a greater degree.

In the banking sector, inhibiting factors which are currently restricting the development of banks were identified in initial interviews. An executive complained of the obligation to deposit RMB500 million (approximately euro 50 million) for capital adequacy purposes for each branch that is opened. This condition does not apply to Chinese banks and, as such, can be seen as a non-tariff barrier. He stated that he is keenly awaiting 1 December 2006, when China is obliged under its WTO commitments to grant national treatment to foreign banks. The banking executive was re-interviewed in 2007. Since then, China had made provision for foreign banks to incorporate in China. (In April 2007 four foreign banks were granted national incorporation by the Chinese regulatory authorities). By incorporating they will move closer to obtaining national treatment and the capital adequacy requirement per branch will be removed. He was of the view that, while not yet perfect, China has made significant strides in opening up its banking sector.

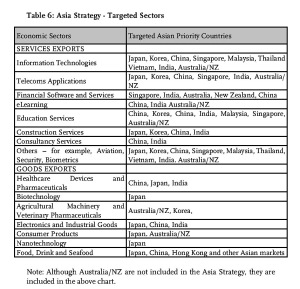

A telecoms executive referred to the high level of state control in the telecommunications industry. The fixed line and mobile network is state-owned and there is scope for investors in the telecoms equipment sector only. An education company executive pointed out that this sector is highly regulated for political reasons. Foreign investors at the third level must have a Chinese institutional partner. ‘There is scope for investors in the international schools sector, which is booming. But even there you need the local government as a partner if you want to have a trouble-free existence’. These issues are of relevance to this research as the Government’s Asia Strategy highlighted these sectors as promising a deeper engagement with China. It is important that these locational challenges should be appreciated by potential investors.

Technology transfer is an important consideration for the Chinese authorities. One executive recounted his experience of the investment negotiations:

‘The Chinese side insisted that we use the latest available technology. This resulted in an USD900million investment. If we had been allowed use lower specification technology, which would have produced much the same output, our investment costs would have been halved’. He suggested that the transfer of technology is very important to the Chinese side in granting approval for investments. This poses a dilemma for potential investors given some of the views expressed on the lack of protection for intellectual property rights. Investors will need to take steps to adequately protect key technology to avoid the proliferation of one’s technology into what one executive described as ‘communal property’.

The issue of recruiting and retaining qualified staff featured as a challenge, in the experience of executives of Irish MNEs. One executive stated that his firm currently employs 1,000 staff and expects this number to grow to 5,000 in five year’s time, although he added ‘if we can find suitable people’. Another who had experienced difficulty with recruiting and retaining qualified experienced staff suggested that the most likely staff member to leave is the number two in each department, as s/he sees little opportunity for advancement. This opinion is corroborated by the view of another executive, who stated that staff retention has not been a major problem as there have been plenty of promotion opportunities. He argued that the availability of opportunities for advancement is more important than pay in relation to staff retention.

Borensztein et al’s (1995) model of endogenous growth, which uses technological progress as the main determinant of long-term economic growth, argues that more advanced technology requires the presence and development of a sufficient level of human capital in the host economy. If this condition is not satisfied, then the absorptive capacity of the developing host economy will be limited. This complementarity between FDI and human capital is evident in the response of virtually all interviewees, where they raise the challenge of recruiting and retaining suitable staff. This limitation may restrict the level of inward FDI in certain industries in future years. It remains to be seen if this limitation is of such magnitude that it could offset the locational advantages which China offers. What can be said at this point is that the executives are keenly aware of human resource limitations. One executive pointed out that these limitations may restrict their expansion plans. To date, however, they have not inhibited FDI growth.

The general experience of investors in the set-up and early stages could be described as time-consuming, bureaucratic, but not particularly challenging. The environment could be seen as no more challenging than investing in any other developing economy. Issues highlighted tended to be of a sectoral specific nature. At this point, drawing on the results of this research, disincentives and barriers to investment will be explored with a view to identifying the particular locational disadvantages which China poses for investors.

Disincentives to Investing in China

The major disincentives and barriers identified were described in response to the questions relating to cultural challenges and perceptions on the role of contract law. The main challenges can be broken down into three distinct areas, viz guanxi, intellectual property rights, and contract law.

Guanxi – Irish MNEs

Executives of Irish MNEs spoke of the importance of networking in the conduct of business affairs. In addition, the need to build relationships with relevant officials was also identified. Executives saw the need to interact and develop stronger relationships with officials as time-consuming and a ‘cost’ which one would not have to incur in Ireland. One executive spoke of initially being quite nervous in dealing with the local authorities at a more intense level than in Ireland – ‘It took quite a while to come to terms with officialdom; they wanted us and were very accommodating. But agreements can be altered by government officials, so we know that we need to have a strong relationship with them’. This statement hints at the historical divergence between China and the West in terms of the power of local officials, as identified by Jones (1994). As set out in chapter two, laws were traditionally open to interpretation and local officials exerted considerable power. While this has changed in recent times, local officials still exert influence, given the role which the state plays in the economy. Therefore, Irish executives see the need to cultivate strong relations with officials as an important component of China’s business culture. This indicates a cultural difference between China and Western economies. As it represents a drain on the resources of investing MNEs, it is a locational disadvantage.

In addition, regional divergences were identified regarding the pervasiveness of guanxi. By and large, executives in the eastern seaboard region recognise the importance of developing strong relationships with business and official contacts, but did not stress the importance of guanxi as traditionally understood. They tended to see relationships in this region as slightly above the normal scope of business. One executive observed: ‘Guanxi is important outside the main economic centres. However, in cities such as Shanghai, doing business is somewhat similar to many other developed economies. Relationship building is important, the same as in any country, except you need to work with officials more’.

The consultancy company executive suggested that:

Since the opening-up policy was introduced, a change in business culture has occurred. Guanxi was important 15 years ago, but is no longer as strong an influence in the major industrial cities on the east coast. This is not to say that business relationships and contacts are any less important than in any other economy. Doing business in eastern China is normalising, but the Government still has a large measure of control over the economy.

The executive of the service MNE stated that ‘Guanxi is very important in southern China, because the government controls industry’. Therefore, if Irish MNEs invest outside the eastern seaboard they are likely to encounter a higher level of locational disadvantage.

Non-Irish MNEs

Executives of non-Irish MNEs also spoke of the need to develop strong relationships with officials because of the level of bureaucracy which one has to contend with. One executive commented that ‘Access is an issue, so I have to devote time to working the local officials. This means that I can solve problems quicker’. Another executive spoke of the regional variation identified by Irish MNEs. This MNE has re-located its manufacturing facilities from Shanghai to a province in the centre of the country. He stated that ‘In terms of guanxi, we seek to build a strong relationship with the local mayor or party secretary, preferably the latter. We use this channel to negotiate difficult issues which we can’t resolve at official level’.[ii]

This view corroborates the observations of Irish executives that there are regional variations in the practice of guanxi in China. Along the eastern seaboard, executives spoke of investing time in developing relations with key officials. However, away from this region, executives spoke of traditional guanxi and the need to develop strong relationships with officials. China would appear to have developed an intricate and pervasive network which investors must take cognisance of. (Luo, 1998)

An interesting observation on Chinese culture was made by the banking executive. He suggested that a positive dimension of Chinese culture which assists banks is the emphasis on guanxi. In his view, banks should be relationship and not transaction driven. Accordingly, he sees a synergy between Chinese and foreign banking cultures. This is of relevance to potential Irish investors as financial services are one of the eight sectors highlighted for deeper engagement with Asia in the Government’s Asia Strategy.

Intellectual Property Rights – Irish MNEs

The lack of respect for intellectual property rights was raised by over half the Irish MNEs as an issue of concern. An executive of a chemical MNE recounted that the technology which they introduced into China has now proliferated throughout their Chinese competitors. ‘Technology is seen as fair game, it is seen as communal property’. The executive of this particular MNE is firmly opposed to introducing its newest technology into China.

The protection of intellectual property was also identified as a key consideration for the food sector. One of these firms is currently planning how to best protect its intellectual property and is looking at importing a key ingredient from abroad to mix with the ingredients manufactured in China. This reflects the view of Lieberthal and Lieberthal (2004) who suggest that critical technologies should be kept outside the Chinese manufacturing process as a means of compartmentalising production and thereby reducing the risk of IPR theft. Another executive pointed out that obtaining trademarks ‘takes longer in China, takes at least 12 months to be reviewed, searched and granted, so this leaves plenty of time for the copying of products’. The executive of an MNE which has a joint venture arrangement spoke of the importance which the parent firm places on protection of intellectual property. ‘We had to pick our partner very carefully and make sure that there is an incentive for them not to leak the intellectual property’.

IPR was not a concern for the Irish MNE which operates in a specialised textiles sector, presumably because the firm is operating in a niche market. One of the IT executives suggested that IPR is seen as posing the same challenges in China as it does in other overseas investments. He stated that he had a clear impression that the Chinese authorities wanted to be seen to be respecting intellectual property rights.

Non-Irish MNEs

The protection of intellectual property rights was also identified as a key concern by over half of the non-Irish MNEs. Counterfeiting was identified as a serious problem for the consumer products MNE. While the products are not of particularly high value, it is nevertheless profitable for counterfeiters to sell low-value substitute produce under the firm’s brand name. Generally, the firm resorts to legal procedures only if the local administration cannot resolve the issue. However, the legal avenue has not always proved successful in the past, particularly if the violation occurred in a province outside the MNE’s manufacturing base. This view was corroborated by a healthcare executive who referred to the challenge of avoiding counterfeiting, ‘which we put a lot of resources into’.

Overall a picture was painted of a less than complete lack of respect for intellectual property rights. Both the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China (2005) and the American Chamber of Commerce Shanghai (2005) highlight the lack of enforcement of China’s intellectual property rights laws. The European Union Chamber (2005: 71) expresses its concern that the enforcement on a national level of the IPR laws in China seems to be performed on the basis of specific high profile campaigns rather than on a permanent basis and is not evenly spread across all regions in China… it is a well known fact that counterfeit products are still found in significant quantities, in open or closed retail markets and that authorities being aware of this fact do not show any initiative to stop such sales.

The most visible expression of such counterfeiting is luxury items available in the markets. The EU Commissioner for Customs and Taxation[iii] expressed concern that the areas with the highest potential for counterfeit and which have substantial health considerations are pharmaceuticals, car parts and aircraft spare parts.

The literature suggests that FDI is a better route to protect one’s intellectual property than licensing production to a third party. (Baranson, 1970; McManus, 1972; and Baumann, 1975) Internalisation also avoids the difficulty of what Buckley (1987) terms the ‘buyer uncertainty problem’ whereby the licensee obtains a transfer of intellectual property, as discussed above.

These considerations are particularly pertinent in the case of China. The threat to a MNE’s intellectual property in China may represent a significant locational disadvantage. (This issue was also cited as a reason not to enter into a joint venture structure.)

Intellectual property is an ownership advantage. Therefore, FDI in China can also pose a threat to an MNE’s ownership advantage. This research indicates that if an MNE is investing in China it should exploit its internalisation advantage and retain the production function internally. In addition, it must be constantly vigilant of the need to protect the MNE’s intellectual property. This is particularly pertinent where hi-technology industries are involved as, should the MNE’s intellectual property be lost, the MNE is effectively left with little ownership advantage.

Contract Law – Irish MNEs

Almost two-thirds of executives identified significant difficulties with the implementation of contract law in China. A view emerged of MNEs trying to cover all eventualities in a contract in the knowledge that, should difficulties emerge, there was little legal redress available. An executive stated:

‘We try to cover everything in the contract but it is a very immature system and very difficult to enforce any breach. It cannot be relied upon, so managing any business relationship smoothly becomes much more important in order to avoid having to try to enforce a contract through court’. Another executive suggested that the ‘quality of contracts in China is very good, probably better than Europe – because we put everything into it. It is written and signed, but how much value is that at the end of the day?’ It was suggested by another executive that ‘courts do not have a sophisticated approach to contracts because this is a trust based society’.

One executive, who had previously had a bad experience with the non-honouring of a contract by a Chinese firm, saw no merit in contracts because ‘They will find ways to walk away… There are no safety nets like you would use in the West. There is no tradition… The courts don’t have the stature to move things along’. In his previous dispute, the firm could not find a competent court which would accept jurisdiction for the case. This occurred ten years ago but gives an indication even today of the lack of a tradition of Rule of Law. An executive with a large manufacturing facility stated that he has ‘no contract with any supplier. The day I put pen to paper, I don’t trust them’. Such an opinion supports the view of Jones (1994), who suggests that the Rule of Relationships is more important than the Rule of Law in China. Overall, a view emerged of executives seeking to negotiate detailed contracts in an effort to cover as many eventualities as possible. However, there was also a recognition that in the event of a dispute, pursuing a legal route was not likely to be the most productive means of addressing it.

Non-Irish MNEs

The views of the previous category are mirrored by executives of non-Irish MNEs. One executive spoke of the detailed negotiations which the MNE’s inhouse lawyer engages in when negotiating contracts. The contracts which the MNE uses in China are much more detailed than in their home economy. They clearly define conditions of delivery, service, etc, which would not require definition in the West. An executive of a pharmaceutical MNE recounted the level of detail which the MNE inserts into contracts but the value of contracts is relatively low compared to Germany or the US. Going to court is worthless. We have had clear cases but the other side declared bankruptcy, opened up another company and the court facilitated it. Contracts are only one small part of an overall relationship. [It’s] just an addendum which reminds people of their rights.

Views of Lawyers

In order to explore further the role of contract law and the general legal framework, interviews were conducted with two lawyers on the specific issues of the legal environment and the role of contracts in the conduct of business in China. The first lawyer is a partner in the largest indigenous Chinese law firm and works exclusively with foreign investing MNEs. The second lawyer is a partner in a large international consultancy firm and specialises in M&A activity by foreign investors.

The first lawyer suggested that one could consider contract law in China as being akin to a test of strength: ‘If one side is in a position of strength, they will seek to include ridiculous conditions in contracts’. He suggests that this occurs when executives do not have a deep and trusting relationship. The second lawyer described contracts involving foreign MNEs as containing ‘much too much detail. Between two Chinese companies it is very simple. He sees the reason for this as the under-developed nature of law in China. ‘In Europe, there is a developed contract law – the law can interpret intentions. But China is a highly regulated society so lawyers advise that agreements must be specific. Therefore, lots of detail’. Later he added that ‘contracts are linked to relationships. Before, the government owned the whole economy, so one’s word was enough. Now, with so much inward investment, things have changed considerably.’

Should a decision be taken to commence court proceedings, the first lawyer suggested that it is much easier to take a case against a publicly listed firm in the province in which the MNE is located than against a private firm in another province. Again, a regional disparity in governance is evident. However, he cautions that litigation is not a happy event. While obtaining a judgement may not be a problem, enforcing it is not easy. Enforcement is just too difficult. Foreigners think they are the only ones who can’t get judgements enforced, but it happens to everyone.

If an MNE is proposing using M&A as an entry vehicle, the second lawyer cautions that normally a deal is worked out based on financial information.

Due diligence normally indicates little divergence. Here, I believe that figures have traditionally not been used to measure performance. In a communist atmosphere, figures don’t matter – just meet production quotas and pay tax. There is no profit motivation. Financial statements are completely different to the West. With the emergence of a private sector, accounts are still wrong. Tax is high, so the accounts are wrong. I suppose the financial statement is not complete, rather than not correct.

Regarding the general conduct of commercial law, the first lawyer identified a trend among foreign investors of seeking to insert a clause that made legal agreements and contracts subject to the legal jurisdiction of the home country. ‘…[B]ut if there is no mutual co-operation agreement, which a lot of countries don’t have with China, then such clauses don’t make sense. It is completely up to the courts in China whether to implement a foreign judgement’. The second lawyer pointed out that much M&A activity is made subject to Hong Kong law. However, he cautioned that unless the Chinese partner has assets in Hong Kong, the merit of this approach is questionable.

Pointing to a general absence of the Rule of Law in favour of the Rule of Relationships, the first lawyer suggested that should a significant issue arise, the easiest and most effective method of dealing with it is to approach the provincial government. The local or county government will support the Chinese firm, but governments at provincial level want to attract more inward FDI so they are likely to support the foreign MNE ‘or at least be neutral’. He recalled several cases which were settled in a satisfactory manner through this channel. However, he would propose this route only when there are significant issue to be resolved and not in the case of a problem with a sales contract.

A regional variation in the administration of law was identified by the second lawyer. ‘Judgements in the east of the country tend to be fair, particularly in Shanghai and Beijing. In other areas, there is a tendency to protect local companies. The application of the concept of separation of powers is questionable’. He expressed the opinion that this has occurred because the focus of the authorities has been on economic development. ‘Developing a legal environment doesn’t have the same priority. The legal system wasn’t well developed under the Communist system. What people say is that it takes too long to get to court. The government doesn’t see developing capacity as a problem to be addressed’. He also identified the lack of the award of damages as an issue which sometimes surprises foreign MNEs when they are considering litigation. ‘Opportunity cost is not compensated. You have to prove how much you lost’.

A picture was presented of contract law having little real impact on the conduct of business. Paradoxically, lawyers seek to cover a greater level of contingencies than in the West when negotiating contracts, but there is a recognition by executives that turning to the courts to impose the conditions which a contract contains is likely to be a costly and often fruitless exercise. Allied to this is the emphasis which executives place on the importance of building and sustaining good relationships. This corroborates the view that the Rule of Relationships supersedes the Rule of Law in China (Jones, 1994). We shall discuss this further in the following chapter.

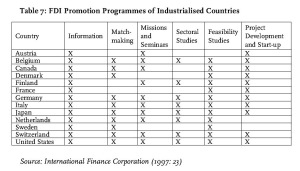

Role of the State

All Irish and non-Irish executives, except one, saw no role for the home country government in providing financial support to investing MNEs. They were of the clear view that it was inappropriate for home governments to subsidise investment overseas and that investment should be undertaken based on clear economic rationale only. Only one executive had received support from his home government. He recounted his difficulty in obtaining start-up capital: ‘It took us over a year to raise the capital for the initial investment. The catalyst for obtaining the funds was when Enterprise Ireland agreed to invest’. When this point was raised with the Enterprise Ireland executive, it was pointed out that the agency made this investment on the basis that the head office and core functions would be located in Ireland. This can be seen as recognition of the importance and added-value which head office operations add to the Irish economy. We will return to this issue in chapter five.

All executives envisaged a role for home government ‘soft’ supports to varying degrees. There was a distinction between large and small MNEs, rather than Irish and non-Irish MNEs. The largest MNEs saw a role for state support in lobbying the Chinese authorities on issues such as national treatment (this was a particular issue in interviews with those from the banking and food sectors) and protection for intellectual property rights. The importance of double taxation treaties as a facilitator for investment was also recognised. The smaller MNEs agreed on the need for lobbying and bilateral taxation agreements but also envisaged a role for additional soft supports. The executive of one Irish MNE recounted how he decided to invest in China following the firm’s participation in a government-led trade mission to China, when he visited the firm’s Chinese customers for the first time. Based on these discussions, he identified China as a potential major market.

The role played by diplomatic missions and state agencies was recognised by respondents in this category. Because of the continuing high level of state involvement in the economy, executives expressed their appreciation of the role which diplomatic missions and state agencies play in terms of making introductions, their presence at events etc. One executive recounted the assistance offered by the home country’s trade and investment agency in resolving an issue with the Chinese authorities. He pointed to the opaque nature of government in China and stated that once his own government became involved, the Chinese side responded.

Several executives of Irish MNEs spoke of the need for an increased level of provision of information by state agencies, particularly in view of the opaqueness of Chinese administration. Also identified was the lack of assigned responsibility to any state body for the provision of assistance or guidance for outward investors. The role played by Enterprise Ireland was acknowledged, but it was pointed out that trade missions do not facilitate investors, nor are potential ‘match-making’ or feasibility studies offered to investors by Enterprise Ireland, as their core focus is on the promotion of trade.

The importance of trade missions was highlighted by one executive who commented that the MNE’s customers ‘are very impressed when we can produce a minister for a signing ceremony. They read this as, us having strong government contacts. But this is so much easier in a small country of only four million, compared to China’.

Overall, there was strong support for ‘soft’ assistance from the state. The divergence in views between large and small MNEs can presumably be accounted for by the fact that large MNEs enjoy considerable access to local authorities and have sufficient strength to resolve issues by themselves.

Investors in Eastern Europe

The industrial sectors in which the Irish MNEs operate are financial services, pharmaceuticals, manufacturing, IT and electronics. Three of these areas, financial, IT and electronics, are suggested in the Irish Government’s Asia Strategy as areas for strengthening links with China. Hence, the views of executives in these industries are of particular relevance.

Just over half of the MNEs invested in Eastern Europe for market potential opportunities, with the remainder deciding to do so because their customers were investing there. Both of these phenomena were also evident in the case of investors in China, but the focus identified by interviewees in Chineseinvested MNEs was primarily on exploiting market opportunity.

In response to the question as to why they invested in Eastern Europe rather than China, the general response was that China didn’t fit in with the firm’s business plan at the time of the investment. Asked if they now considered that they should invest in China, all were non-committal. One executive suggested that ‘things can be controlled easier close to home. We know the environment’. Another said ‘We were facing competition from other European countries and central Europe matched up. We looked at China two years ago. We have no interest in a greenfield site. We are not big enough and don’t have management depth’. An executive of a pharmaceutical MNE stated that ‘We don’t follow low wage economies. In the hi-tech pharmaceutical industry there are a different set of entry principles. In other industries there are low entry barriers, but not in ours’.

The perceptions of the regulatory and cultural environments centered on the lack of respect for intellectual property rights and contract law. An IT executive spoke of his concern about the lack of IPR protection and was not convinced that he could protect his patents through the legal system. A pharmaceutical executive recalled that intellectual property accounts for 80% of the value of the MNE and stated in strong terms that intellectual property is the lifeblood of the MNE so it must be protected (the firm has an in-house team of lawyers for this purpose).

The electronics executive spoke of there being ‘no enforceable rights’ when the question of contract law was raised. All executives spoke in similar terms, saying that they had no expectation that their intellectual property could be protected by contract law or by the legal system in the event of a dispute. The consensus was that the legal system is not sufficiently mature to enforce their rights. It should be borne in mind that these views are perceptions from a distance, as these firms have no engagement with the Chinese economy.

A financial services executive referred to a strong level of state control in the banking sector in China. When the fact was raised that other international banks have shown an interest in acquiring holdings in the ‘big four’ Chinese banks, he replied that the maximum shareholding they are being permitted to acquire is 20% at a very expensive price. The Irish financial institution would have an interest in the provision of corporate banking only, if it were to ever consider investing. His perception is that the retail market ‘is sown up by state banks’.

The executives interviewed did not express particularly strong views on the cultural dimension of investing in China, which is understandable given their lack of engagement with China. Issues such as cultural difference and corruption were mentioned, but not as insurmountable barriers to investment. The principal barriers identified were regulatory/legal. All interviewees saw a role for diplomatic missions, government-led trade missions and the support of state agencies in assisting entry into the Chinese market. Similar to the views of investors in China, there was support for ‘soft’ assistance only. The views of executives in this category are not based on direct experience of investing in China. The perceptions offered on IPR protection and contract law corroborate those of executives whose MNEs have already invested in China. Generally, there was little recognition of the potential market opportunity which China offers. However, executives from the same five industries, which have already invested in China and which are included in this research, pointed to the locational advantage which China offers in this respect. It can be assumed that the Irish MNEs which have invested in Eastern Europe possess ownership and internalisation advantages. The size of these MNEs is not dissimilar to that of the Irish MNEs which have already invested in China. Therefore, what factors are inhibiting their willingness to exploit the locational advantage which China offers? The main reason cited is the lack of legal protection for intellectual property, should they invest in China. Accepting that the population included in this category of the research is small, it can be argued that there is an acknowledgement among sections of Irish industry that investing in China exposes a firm to the risk of IPR violation.

Conclusion

There was a clear consensus among both Irish and non-Irish investors in China that the locational advantage which China offers, as understood by Dunning, is market opportunity and this is the principal criterion underlying investment decisions. Of particular interest to our consideration of Barry et al’s model is the fact that just over 80% of Irish MNEs are in the traded sector. This research indicates that the current wave of Irish FDI into China differs from the model of Irish outward FDI identified by Barry et al (2003) in the case of the UK and US, and that the hypothesis advanced in this research holds, namely that Irish FDI into China does not conform to Barry et al’s model in the case of China. Irish FDI into China was found to be largely in the traded sector and could not be described as disproportionately horizontal.

While just under 20% of Irish MNEs have joint venture structures, the clear preference of investors not to enter into joint venture arrangements with Chinese partners is apparent. Instead they wish to establish Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprises (WFOEs), where they can retain full control of operations. The preference toward the establishment of WFOEs reflects ‘the decreasing dependence of MNEs on the Chinese government for marketing support, the diminishing reliance on Chinese partners because of the acquired experience and more entrenched position by the foreign investors and especially the relaxation of the foreign ownership regulations’. (Van Den Bulcke et al, 2003:68) It also reflects the manner in which MNEs wish to exploit the internalisation advantage which they possess. The preference in favour of WFOEs is also important as a means of protecting the MNE’s ownership advantage, in the form of intellectual property rights. The risk to IPR and the absence of enforceable contract law were identified as the most significant disincentives to investing in China. These views were supported by Irish investors in Eastern Europe. These disincentives represent a challenge to the ownership advantage of MNEs.

The executives interviewed paint a picture of companies which are taking a long-term strategic approach to investing in China, rather than having a focus on short-term profits. They see their investment as adding value to their global operations, in particular the locational advantage which China offers in market opportunity. However, the challenges associated with investing in China should be borne in mind. At this point, we shall turn our attention to specific consideration of such challenges before presenting views on the nature of and prospects for Irish inward FDI into China.

NOTES

[i] The reference to increasing tax refers to a move to harmonise tax rates for foreign and Chinese firms, which is required under WTO rules.

[ii] In the Chinese political system, a Mayor is the public face of local government and manages affairs on a day-to-day basis. However, a Party Secretary de facto out-ranks a Mayor and is responsible for the determination of key policy issues.

[iii] Commissioner László Kovács addressing Consuls General in Shanghai, May 2006