Lauren Quinn – Hanoi: Is It Possible To Grow A City Without Slums?

guardian.com. August 2014. To an outsider, Hanoi can seem like a city trying to consume itself. Jackhammers chatter and circular saws whine like cicadas. Sparks from welding shoot into oncoming traffic and exhaust fumes lace the air with a metallic twinge. Careening through the streets on the city’s estimated 4m motorbikes, people drape mesh netting over their babies’ faces to block dust from construction sites, while women in conical hats dig through the rubble of newly demolished lots for scrap metal. The intense humidity causes mould to sprout, paint to peel, wood to rot.

On a typical Hanoi wall, crisscrossing layers of plaster, paint and mildew, you will see a multitude of stencilled adverts, all with similar fonts and a string of numbers beginning with 09, and all including the letters KCBT. It’s an abbreviation for khoan cắt bê tông – concrete cutting and drilling. These are illegal adverts for demolition services, and they tattoo the walls of the city, as if to say, “See this building? It could be gone tomorrow.”

Read more: http://www.theguardian.com/hanoi-slums

Pierre-Dominique Gaisseau – Sur la carte du monde: une tache blanche en moins…

Interview de Pierre-Dominique Gaisseau, à propos de sa récente traversée de la Nouvelle Guinée, région du monde jusque-là inexplorée. Il raconte l’expédition en commentant les images qu’il en a rapporté.

Jordan G. Teicher – A Stroll Through Ireland’s Eerie Ghost Estates – Photo’s: Valérie Anex

From the mid-1990s through 2006, home prices in the Republic of Ireland increased steadily, fueled by a period of economic prosperity known as the Celtic Tiger. In 2008, the property bubble burst, and investors who’d built housing developments in remote rural areas found themselves unable to sell their properties or, in many cases, even finish their construction.

Valérie Anex, an Irish citizen who grew up in Switzerland, was in County Leitrim in 2010 when she first came across ghost estates—defined by the National Institute for Regional and Spatial Analysis as a development of 10 houses or more in which 50 percent or less of homes are occupied or completed. Anex was astonished to learn that ghost estates were common all around the country. “The house is an object full of very strong symbols,” she said via email. “It is inevitable that when people discover through my images the existence of these inhabited brand-new houses, they start to ask themselves: What has happened? What are the historical forces that lead to this absurd situation? How is it possible to construct houses if there aren’t any people willing to live in them? Where does this surplus come from? Why this waste of labor, resources and energy?”

Read & see more: http://www.slate.com/val_rie_anex_photographs

Derek Markham – Shipping Containers As Building Blocks For Vertical Urban Farms

popularresistance.org. August 2014. One potential solution for producing more food in the city, while recycling waste and water, is creating modular vertical farms from shipping containers, such as Hive Inn City Farm.

Where there’s plenty of usable space, farms and gardens can be as spread out horizontally as the grower has room for, but in the city, where physical space is a very limited resource, the only possible place for urban farms to grow is up, and one design studio believes the best way to do that is through vertical shipping container farms.

The need for standardization for space-efficiency in the shipping and cargo industry led to creation of the ubiquitous shipping container, and this design, due to its inherently modular nature and rugged construction, has been the focus of a recent repurposing renaissance. Shipping containers already make great portable storage units, without any modifications, but they also lend themselves to being used as homes, offices, and food production systems with a bit of customization.

One idea for repurposing shipping containers in the city comes from the Hong Kong design studio OVA, the firm behind a shipping container hotel concept that Lloyd previously covered, but their Hive-Inn City Farms design takes aim at urban food production instead of lodging.

Read more: http://www.popularresistance.org/vertical-urban-farms/

The History And Context Of Chinese~Western Intercultural Marriage In Modern And Contemporary China (From 1840 To The 21st Century)

Table of Content

Abstract

Chapter One – Introduction

Chapter Two – An Intellectual Journey: The Theoretical Framework

Chapter Three – Mapping the Ethnographic Terrain: The Methodological Framework

Chapter Five – The Process of Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage in Contemporary China

Chapter Six – Why do they marry Westerners? Motivations and Resource Exchanging in Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriages

Chapter Seven – Conflicts and Adjustments in Chinese-Western intercultural Marriage: A Cultural Explanation

Chapter Eight – Epilogue

Bibliography

Appendix I: Interview Questions Guide

Appendix II

Abstract

Intimate relationships between two people from different cultures generate a degree of excitement and intrigue within the couple due to that very difference, however this also brings its own challenges. Intercultural marriage adds an extra set of dynamics to relationships. Although the Chinese culture is very different from Western culture, individuals from both nevertheless meet and fall in love with each other. The existence of intercultural marriages and intimacy between Chinese and Westerners is evident and expanding in societies throughout both China and the Western world. This thesis aims to present a true picture of Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage (CWIM) with a focus on the Chinese perspective.

By employing a three-dimensional, multi-level theoretical framework based on an integration of theories of migration, sociology and gender and adopting a qualitative research paradigm, the main body of this study combines three theoretical approaches in order to explore CWIM fully using a panoramic view. The first part of the study is conducted from a macro-level perspective. It provides a historical review of intercultural marriage and transnational marital systems in Chinese history from the modern to the contemporary era through a discussion of the different characteristics of CWIM. The context and background of Chinese intercultural marriages in modern and contemporary China are also reviewed and analysed, such as the related regulations, laws, governmental roles, and so on.

The second section is conducted from a middle-level perspective. On the basis of the study’s fieldwork, the demographic characteristics of the respondents are first disclosed, and different patterns are identified as occurring in CWIM. The approaches to and motivations of CWIM are examined, and a framework of CWIM Push-Pull Forces and a model of Resource Exchanging Layers are established to explain how and why Chinese people have married Westerners. The exchanges and Push-Pull force components operating in Chinese-Western intercultural marriages are also discussed.

The third section offers a micro-level examination of the research, and it moves on to discuss the family relations in Chinese-Western intercultural marriage, particularly with the entrance of a member of a different culture into the Chinese familial matrix. This part of the study focuses on cultural conflicts, origins and coping strategies in Chinese-Western intercultural marriage with an emphasis on the experiences of Chinese spouses. Five areas of marital conflicts are revealed and each area is analysed from a cultural perspective. The positive functions of conflicts in CWIMs are then explored. The six coping strategies and their frequencies of usage by Chinese spouses are further examined.

The final chapter will summarise the points examined previously and will unravel the factors underlying CWIM by recapitulating the symbolic significance, social functions and gender hegemony represented in Chinese-Western intercultural marriage. In this way this study will provide more than an anecdotal description of Chinese-Western Intercultural marriage, but will present a profound analysis of the forces underpinning this cross-cultural phenomenon.

Key Words: Chinese-Western Intercultural marriage, History, Cultures, Motivation, Exchange, Marital Choice, Conflicts.

List of Abbreviations

CCP – Chinese Communist Party

CCW – Chinese Civil War

CH – Chinese Husband

CPC – Communist Party of China

CHWW – Chinese husbands & Western wives

CW – Chinese Wife

CWIM – Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage

CWWH – Chinese wives & Western husbands

DIL – Daughter in Law

EU – European Union

FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

FS – Foreign Spouses

IC – Intensity of Conflict

KMT – Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party)

LS – Local spouses

MIL – Mother in Law

MM – Marital Migrants

PRC – People’s Republic of China

ROC – Republic of China

TP – Third Parties Records

USSR – Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

VC – Violence of Conflict

CWWH – Marriage of Chinese Wife and Western Husband

CHWW – Marriage of Chinese Husband and Western Wife

WPA – Western Physique Attraction

The History And Context Of Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage In Modern And Contemporary China (From 1840 To The 21st Century)

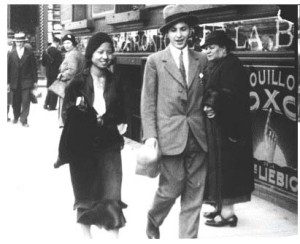

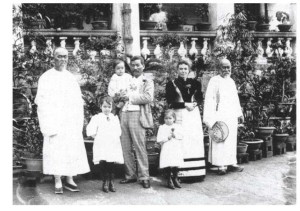

Australian wife Margaret and her Chinese husband Quong Tart and their three eldest children, 1894.

Source: Tart McEvoy papers, Society of Australian Genealogists

1.1 Brief Introduction

It is now becoming more and more common to see Chinese-Western intercultural couples in China and other countries. In the era of the global village, intercultural marriage between different races and nationalities is frequent. It brings happiness, but also sorrow, as there are both understandings and misunderstandings, as well as conflicts and integrations. With the reform of China and the continuous development, and improvement of China’s reputation internationally, many aspects of intercultural marriage have changed from ancient to contemporary times in China. Although marriage is a very private affair for the individuals who participate in it, it also reflects and connects with many complex factors such as economic development, culture differences, political backgrounds and transition of traditions, in both China and the Western world. As a result, an ordinary marriage between a Chinese person and a Westerner is actually an episode in a sociological grand narrative.

This paper reviews the history of Chinese-Western marriage in modern China from 1840 to 1949, and it reveals the history of the earliest Chinese marriages to Westerners at the beginning of China’s opening up. More Chinese men married Western wives at first, while later unions between Chinese wives and Western husbands outnumbered these. Four types of CWIMs in modern China were studied. Both Western and Chinese governments’ policies and attitudes towards Chinese-Western marriages in this period were also studied. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, from 1949 to 1978, for reasons of ideology, China was isolated from Western countries, but it still kept diplomatic relations with Socialist Countries, such as the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries. Consequently, more Chinese citizens married citizens of ex-Soviet and Eastern European Socialist Countries. Chinese people who married foreigners were usually either overseasstudents, or embassy and consulate or foreign trade staff. Since the economic reformation in the 1980s, China broke the blockade of Western countries, and also adjusted its own policies to open the country. Since then, international marriages have been increasing. Finally, this chapter discusses the economic, political and cultural contexts of intercultural marriage between Chinese and Westerners in the contemporary era.

1.2 Chinese-Western Intermarriage in Modern China: 1840–1949

In ancient China, there are three special forms of intercultural/interracial marriages. First, people living in a country subjected to war often married members of the winning side. For instance, in the Western Han Dynasty, Su Wu was detained by Xiongnu for nineteen years, and married and had children with the Xiongnu people. In the meantime, his friend Li Ling also married the daughter of Xiongnu’s King[i]; In the Eastern Han Dynasty, Cai Wenji was captured by Xiongnu and married Zuo Xian Wang and they had two children.[ii] The second example is the He Qin (allied marriage) between royal families in need of certain political or diplomatic relationships. The (He Qin) allied marriage is very typical and representative within the Han and Tang Dynasties. The third example is the intercultural/interracial marriages between residents of border areas and those in big cities. As to the former two ways of intercultural/ interracial marriage in Chinese history, the first one happened much more in relation to the common people plundered by the victorious nation, while the second one was an outer form of political alliance. The direct reason for the political allied marriage was to eliminate foreign invasion and keep peace. In that case, when the second form went smoothly, the first form inevitably ceased, however, when the first form increased, the second form failed due to the war. Read more