I. Introduction

I. Introduction

This paper discusses creativity and independent thinking in Chinese culture and education. Though focusing on China, it also poses the deeper pedagogical and philosophical question of how to make people creative. The question is something of an oxymoron. For it would seem that in the process of making others creative, the actively creative agent is the one who makes them so, and the outcome, namely the creative student, a passive creation. In fact, the oxymoron reveals an illuminating point. We most probably cannot make others creative. We can only enable them to make themselves creative or facilitate their enhanced creativity. In order to become creative, one must make oneself so.

Creativity is therefore not something to be taught, and in many cases, teaching may even reduce creativity. From the moment of their birth, human beings display a most tangible kind of creativity by inventing, entirely on their own, ways to interact with their surroundings. But then many unlearn their inventiveness through the systematic standardisation of our schooling system – they learn how not to be creative. This is far from being a problem restricted to China but is present in all places presiding over a institutionalised school curriculum.

Institutionalisation and standardisation contain the danger of excessive concentration of the uniform structure per se at the expense of generating diversified outcomes to which the structure should be conducive. Thus, ever since creativity and independent thinking began to be considered desireable traits in the West a few centuries ago, they have been and still are among the most consistent conundrums of the various Western education systems.

But in contemporary China, it seems, the problem is particularly pressing. Chinese educators, entrepreneurs, parents and even the odd politician worry in particular about the inability of the Chinese education system to produce creative and independent thinkers. Among these, many believe that without such characteristics, China’s future capacity to maintain economic growth and a continually stronger position in global politics will be endangered. There is certainly a strong element of truth in this, as will be discussed in the following, but I also argue that the concentration tends to start on the wrong end, to be, so to speak, on the “wrong” kind of creativity, a kind that can be sustained only with great difficulty if a deeper, more underlying kind of creativity is not fostered as a basis.

Before proceeding further in this analysis, some of the vocabulary applied in these pages require clarification. For “creativity” is far from being a self-explanatory concept. Rather, how it should be defined and understood has for a long time been and is still being discussed and debated in various academic, artistic and other circles.

II. Understanding Chinese Creativity

The meaning of creativity depends largely on certain cultural assumptions that may not always be entirely known to us. Different cultures may rest upon a metaphysics or cosmology that engenders divergent conceptions of creativity. In Western culture, while certainly containing divergent views of creativity, the dominant understanding can be traced back to the Judeo-Christian notion, influenced by classical Greek philosophy, of creatio ex nihilo, creation from nothing, according to which God created the world out of the great void. This fundamental understanding of the world as a “personal creation” seems to have had an impact upon virtually all later conceptions of creativity in the Western (Christian) world. To be creative has been regarded as a production of some thing, idea or design out of nothing but one’s own selfhood. It has to emanate from there, for otherwise it would tend to be considered an insincere act of copying or plagiarism, or a “mere” rearranging of something that already exists. Creativity is necessarily tied to the mysteries of the self and its spontaneous faculty of imagination.[i] Creativity consists, by definition, in originality.

Just as Western metaphysics is fundamental for coming to an understanding of Western notions of creativity, comparable Chinese notions rest upon Chinese views of the world. Traditional Chinese metaphysics, however, travels its own path. In Chinese views of the world, cosmogony, while certainly existing, has never played a prominent role. In other words, how the world originally came into existence has not had a bearing on the way in which the world is understood.[ii] The classical Chinese worldview is that of wanwu 万物, literally “ten thousand beings” or simply “all the things that exist”. The wanwu is in a continuous state of flux, that is to say, it is continuously arranging and rearranging itself according to tendencies inherent in the self-engendering (ziran 自然) process illustrated through the interaction of yin 阴 and yang 阳. Where the wanwu originally came from, or whether it originally came from anywhere at all, is not really an issue. In such a world, creativity is not an act through which something new is generated out of nothing (or the self), but one through which an advantageous or productive configuration is achieved of a certain field within the wanwu on which one happens to be currently focusing.[iii] From this point of view, creativity consists in making use of what one has in the best possible way, in making the most of one’s circumstances.

Both ancient Chinese thought and contemporary practice exemplify this sort of creativity. The Classic of Changes (Yijing 易经) and the Classic of the Way and the Virtue (Daodejing 道德 经) portray the world as a holistic process in which its components are continuously transformed. Even the well known section 42 in the latter, often interpreted as expressing some sort of cosmogony, conveys precisely this continuity of the world process: 道生一,一 生二,二生三,三生万物.[iv] What it does not say here is that the way “originally” created the one, the one two, and so on, but that this is an ongoing process in which one thing gradually gives rise to the multiplicity of all things in the world. The way is not a creator, but rather the ongoing world process itself according to which things both come into existence and cease to exist.

Seeking to adopt practice in conformity with the workings of the ten thousand things, the Daoists present the most manifest example of a continuously transformative human living. In the Daoist classic, the Zhuangzi 庄子, we are told of the sages who preserve their own “constancy” within the flow of things by changing along with them in their continuous flux. [v] Being “constant” in this sense does not imply being static or stagnant; in fact, quite to the contrary. By continually reconfiguring their stance vis-à-vis previously unencountered circumstances, the sages are capable of handling them in a productive and effective manner. While this feature of Daoism is hardly debatable, one may ask whether anything comparable applies to Confucianism, which, after all, had the greatest influence on Chinese education.

Confucianism is commonly regarded as a philosophy of static or even reactionary tendencies that resists creative adaptations. But this is a highly misleading image derived from the state of the Confucian philosophy at the end of the last Chinese dynasty, the Qing. As is well known, Confucius certainly stated that he was simply a transmitter of past wisdom, but not an innovator.[vi] While often taken as evidence of the conservative spirit of the teachings of Confucius, this statement appears, however, merely to exemplify Confucius’s own modesty as well as his respect for the cultural tradition. For the aim is not a mere preservation. Confucius is also to have said that “learning without reflection results in confusion, reflection without learning results in peril.”[vii] While the latter part of this statement refers to irresponsible and narrow speculation without considering overall consequences, the first part is a clear disapproval of mere preservationism. The character wang 罔 , translated above as “confusion,” can also mean “disorientation,” and, in fact, Zhang Weizhong, a commentator of the Confucian Analects, explains it as “disorientation that leads to nothing.”[viii] Evidently, those who simply stick to old methods and norms without reflecting on how to adapt them to new situations are unlikely to be successful in their efforts. They will effect nothing. In the Zhongyong 中庸, Confucius is reported to have said that those who are “born into the present age and yet return to ways [dao] of the past will cause themselves misfortunes.”[ix]

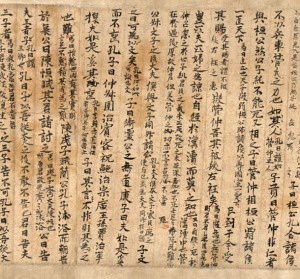

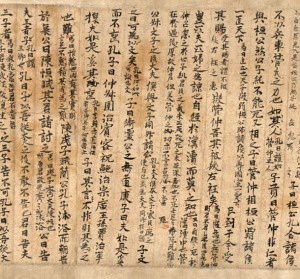

An ancient script of Confucius’ Analects.

outernationalist.net

In the Analects, moreover, Confucius says that “one who realises the new by reviewing the old can be called a proper teacher.” [x] Confucius thus emphasises the importance of re-evaluating the tradition. Tradition is surely of vital importance as a foundation for proper behavior, but it should not dictate it in a dogmatic manner. Instead, proper behavior should be formulated with regard to a critical re-examination of the tradition itself. [xi] The most concrete form of such an examination entails personalisation of the values and practices that constitute it, for new situations continuously call for new responses within the framework of its paradigms. Such responses, when thoughtful, take into consideration the relevant values and past practices belonging to the tradition. However, it is up to the agents as concrete persons to reinterpret the significance and meaning of these values and practices by constantly adapting and re-adapting them to the current circumstances. “Proper behavior” is therefore not only proper in the sense of conforming to traditional values and practices ⎯ it is also “proper” in the sense of being the manifestation of personal “appropriation” of the tradition as such. By responsibly continuing the tradition, persons make it their own; make it “proper” to them.[xii] And, obviously, this can be done in a multiplicity of ways. Openness is guaranteed through the virtual infinity of diverse personal character-traits. Confucius would therefore surely agree with the communitarian philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre’s argument that “[t]raditions, when vital, embody continuities of conflict.”[xiii] The point is not to return to the ancient ways, or the ancient tradition. The Confucian junzi zhi dao 君子之道, the way of “refined,” “cultivated” or “edified” persons,[xiv] the ideal human way within the way of the world, refers precisely to the endeavor to continue forging the path that constitutes the tradition, to continue making the tradition, for otherwise it is not tradition (chuantong 传统) but dogmatic orthodoxy (zhengtong 正统) – tradition that has been ossified.[xv]

Throughout the history of China, Confucianism operated and even approached itself in such manner. The Confucian classics were interpreted and reinterpreted with regard to the needs of the day. Thus, when writing commentaries to these texts, there was, at least up to the late Ming dynasty, a conspicuous absence of an attempt to to explain the text in question by getting to its “original” and “only true” meaning. Instead, the dialogue was continued in such a way that the ideas expressed in the texts evoked the commentators’ own ideas and inspired them to elaborate them further. The French sinologist François Jullien puts it in such a way that “the commentaries have not set themselves up as hermeneutics. Instead of interpreting, they elucidate.” [xvi]

Recent scholarship on the historicity of Confucianism has expressed similar views. For example, Chun-chieh Huang (Huang Junjie) says, speaking of the neo-Confucians’ reading of the Mencius: “During the prolonged dialogues back and forth among [Zhu Xi] and his disciples we never find them regarding the Mencius as an objective text unrelated to their personal lives. They all blended their life experiences into their various readings of the Mencius.” [xvii] Not surprisingly, this constant elaboration of the classics has also resulted in a confusion as to how to characterise Confucianism in general without specifying particular perspectives, periods or even thinkers. It would, indeed, seem more appropriate to approach Confucianism as a temporal-specific, non-essentialisable kind (or indeed, kinds) of philosophy, which, through human intervention and creative interpretation, was (or were) in a process of constant change and adaptation to the particular historical circumstances.[xviii] It is not so much that such an approach prompts us to question whether we can speak of Confucianism as a consistent school of thought; it rather compels us to be more careful when applying labels of demarcation to any streams of thought in Chinese culture, since their open-endedness and flexibility appear as an almost “universal” hallmark. [xix]

An indication of an explanation of this peculiarity consists in the Chinese approach to tradition. A good case in point is the Song-dynasty philosopher Lu Jiuyuan (also known under his literary name Lu Xiangshan). Lu perhaps more explicitly than others formulated the nature of this interaction when he said that just as “the six classics interpret me, I interpret the six classics” (六经注我,我注六经).[xx] Just as we condition cultural artefacts by interpreting them, we are equally conditioned by those very artefacts. All in all, it is also I who interpret the six classics and thereby continue forging the ongoing cultural narrative, forging the “way” ahead. Confucius formulated perhaps the most powerful expression of this attitude or approach to the world when he said: “It is the human being who broadens the way, not the way that broadens the human being” (人能弘道, 非道弘人).[xxi] Whether we understand the “way” (道) as a human construction, as “teachings” or “culture,” or as a cosmological propensity of the world, Confucius is reminding us that we, as living, thinking and acting human individuals, must not allow ourselves to be entirely conditioned by the way as it is at any given time. We should not submit unconditionally to tradition nor to the natural forces, but are instead responsible for its elaboration and/or creative adaptation to the present circumstances: to interpret, to understand, is simultaneously to develop and to create. Novelty emerges from new arrangements of present configurations.

Two main tendencies characterising classical Chinese creativity can be derived from this. First, it endeavours to rearrange what is already present with regard to present circumstances, and secondly, it reaches out to the past in order to extend the present towards the future. An effort to create something new out of “nothing” is, for the most part, absent.

This tendency has also been identified in contemporary Chinese practice, though undeniably with somewhat condescending or humble overtones, depending on where it comes from. Western sceptics have expressed the view that there is no need to fear competition of Chinese technology, since “China is all broth and no noodle.”[xxii] Scientific breakthroughs are beyond China, they say, due to its “shortage of national champions and its dependence on foreign technology.”[xxiii] Conversely, the Chinese themselves seem to overlook their creative potency. A giant Chinese company such as Huawei humbly considers a truly original and simplifying modification of its mobile-phone base-stations as “merely an improvement in engineering processes” instead of real innovation worthy of the name.[xxiv] Analysts have noted that the strength of Chinese technology “lies in ‘trolling’ through existing technologies and components, and combining them in new ways.”[xxv] A good example is Haier, as told by Donald Sull at London Business School: “Haier’s repairmen found that rural customers used their washing machines to clean vegetables, as well as clothes. Its response was to widen the drainpipes that might clog with the peels.” [xxvi] Besides the adaptative response on Haier’s end in this particular case, the creative use of the washing machines by the “rural customers” should not be overlooked.

III. Teaching Creativity in China

Given that the Confucian philosophy approaches existence in such a personalised, creative way as described above, it would clearly have to be capable of conveying that way to those who aspire to learn it. In other words, it must preside over an applicable teaching method if it is not to be a mere armchair philosophy. And indeed, the early Confucians offer us two kinds of teaching method, the verbal and the performative. From the ways in which these are carried out one can see the complementarity and connection between them. “Verbal method” refers to teaching through dialogue. In the Chinese tradition, dialogue is broadly conceived as a continuous process of elucidation in which the teacher is meant to inspire the student to come up with his or her own elaborations of the original ideas. Thus, in such a dialogue, a “teacher” could also be understood as a text and the “student” the reader and interpreter of that text. This partly accounts for the long scholarly tradition of writing commentaries to canonical texts as discussed above.

The major part of the Confucian Analects is a particularly conspicuous example of the priority of incitement over dictation. This accounts for the virtually infinite richness drawn from it by Chinese commentators of the Analects for the last two and a half millennia, but, interestingly, also for its general failure to leave an impression on Westerners who tend to be disappointed by its lack of theoretical argumentation and “rational” systematisation. This is not merely a question of comprehension. For the Master, when responding to the questions posed by his disciples, tends to perplex not only his readers but also his own disciples by being extremely laconic and vague. The clear expression of their perplexity in the Analects is certainly not without significance. Moreover, many of his answers also appear to be mere platitudes or tautologies, and he often responds differently to the same question on different occasions.

www.chinaeducenter.com

There are some passages, however, where Confucius provides a hint of an explanation, or at least a rationale, for his own method. For example: “If, when showing [the students] one corner and they do not return with the other three, I do not repeat myself.”[xxvii] Confucius’s ideal students are those who elaborate on his vague “sketches” and succeed in depicting a whole picture. On one occasion he discusses some sayings with his disciple Zigong who subsequently illustrates the Master’s answer with an appropriate quote from the Book of Odes (Shijing 诗经). Confucius responds to Zigong’s performance by praising him for being able to infer what could follow from the point he himself made initially.[xxviii] I say could follow, for, as will be clear, Confucius is not fishing for one particular answer; the “other three corners” are not already fixed in their concealment and need merely be discovered. Confucius is not just a master of riddles. Nor is it the otherwise perfectly valid and valuable point, important in Plato’s Meno and common in contemporary pedagogic theory, that by making the students go through the entire process for realising the answer one will help them acquire a better and fuller understanding of the issue than if one simply told them the answer. The method of “hinting” certainly serves the purpose of inciting the students to reflect on the issue and develop their own understanding of it. But the key point consists precisely in “their own understanding,” or, more appropriately, considering the practical nature of understanding in Chinese thought, “realisation.”

This can be seen from another Analects passage, where Confucius asks Zigong to compare himself with the prodigy-student, Yan Hui. Zigong responds: “How could I dare comparing myself with Yan Hui! On learning one thing he realizes ten. I myself, on learning one thing, realize the second.” Confucius says: “You are not his match. Neither I nor you are his match.”[xix] In his translation of this passage, James Legge provides an illuminating elaboration on its fuller meaning. The Chinese character for “ten” (shi 十), by representing the four cardinal directions as well as the centre, is also associated with completion or entirety.[xxx] Thus Legge translates as: Hui “hears one point and knows all about the subject.” The implication of this passage, as François Jullien has noted, is that “the slightest indication bears fruit in” Yan Hui and that he can develop the lesson to the end on his own. On the other hand, when Zigong learns something, he can also complete it, but remains “limited by a successive progress, which is flatly deductive, without rising to universality.”[xxxx] Yan Hui’s superior ability consists in perceiving the opportunities and possibilities for development proceeding from the initial point. This interpretation is further supported by Confucius’s comment at the end, that neither he nor Zigong is Yan Hui’s match. Confucius perceives Yan Hui’s productivity or creativity as being superior to his own.

In the section on learning in the ancient Book of Rites (Liji 礼记), this hinting-method is spelled out even more clearly: When junzi 君子 have realized the sources for successful teaching, as well as the sources that make it of no effect, they are capable of teaching others. Thus, when junzi teach, they lead and do not herd, they motivate and do not discourage, initiate but do not proceed to the end. Leading without herding results in harmony; motivating and not discouraging results in ease; initiating without proceeding to the end results in reflection. Harmony, ease and reflection characterize efficient teaching. … Good singers induce people to carry on developing the tunes. Good teachers induce people to carry on developing the ideas. Their words are few but

efficient, plain but outstanding, with few illustrations but instructive. Thus they are said to carry on developing the ideas.[xxxiii] That good teachers “initiate but do not proceed to the end” means that they only hint at the path, but do not spell it out in detail. If they proceed to the end, they are dictating, or, indeed, indoctrinating, but not teaching. Although students initially acquire modes of action from within the parameters of the tradition, it is imperative that they be given sufficient leeway to refine and realise their own personalised modes, because tradition’s main evolutionary drive consists precisely in such modes. Thus, if the teachers also “proceed to the end,” they obstruct this evolution and prevent the tradition from growing. Put in another way: the path, instead of continuing, will only lead back to the starting point.

The Confucian philosophy of education is therefore in accordance with the general Confucian concentration on practical action over speculation. In fact, it would be difficult to see how that could not be the case. If the purpose of education is to enhance knowledge and wisdom, and, in turn, knowledge and wisdom are understood principally as the ability to handle affairs efficiently, then education will largely revolve around ways in which how best to enable the student to develop skills to manage real affairs. Thus, a performative mode of education, a mode in which the student gains first-hand experience, is emphasised even more than the verbal mode. After all, as it says in the Records of Learning (Xueji 学记), a chapter of the Rites: “Teaching is [only] the half of learning” (xue xue ban 学学半).[xxiv] The point of Confucius’s vague incitements is to make the disciples ponder his words, develop their own understanding, and then act on that understanding. Understanding (zhi 智) must lead to action (xing 行).

For this reason, education is to a significant part left to the students themselves. It is only through self-education or self-cultivation (xiushen 修身) that we may hope that individuals keep developing and adapting society to the always unpredictable forces of circumstances. To go back to the problem posed at the beginning of this paper, it is in this sense that they make themselves creative. The task of teachers is merely to stimulate students to search for appropriate ways to figure out or handle their respective subject-matter. If the teachers dictate answers, they prevent a natural evolution of approaches to the constantly changing circumstances. They teach orthodoxy but do not maintain, that is to say, carry further, tradition.

Now obviously this contradicts the received image of Confucianism, and in Chinese history one finds many instances of Confucian teaching methods that, apparently, refute this interpretation. This is true enough and rests upon some problematic aspects of the Confucian philosophy of education. First of all, the method cannot be based on something of a “blueprint” as it must constantly adapt itself to both subject-matter and learner. And secondly, not everyone is able to master it, perhaps even only a few, while any given society requires a large number of teachers. These problems are characteristic of ambitious philosophical ideas, and ones that most, if not all, philosophies have to deal with when successful. And undeniably, Confucianism’s official status in the Chinese empire brought it towards ossification.

Nevertheless, it appears that until the latter half of the sixteenth century, Confucianism’s drive as “creative traditionalism” enoyed, for the most part, considerable success in the dynasties in which had a strong foothold, most notably the Han, Tang and Song dynasties. The civil service examination system, originally initiated under Emperor Wu of the Eastern Han dynasty, had its weaknesses and limitations, and was subject to manipulation by the wealthy and powerful, but it still contributed to a modestly successful meritocratic hierarchy that probably reached its zenith during the Song dynasty.

After the Song, however, the system seems to have lost its dynamic qualities. The evolution of Confucian scholarship during the Ming and Qing dynasties is a fascinating but immensely complicated topic involving a number of various social and philosophical factors, on which only a few summarising comments can be offered here.

While in many ways understandable that the early Confucian focus was on society and social stability in the dire conditions under which it was produced and developed, it should have been a stimulant for other foci in different circumstances, i.e. in times of relative peace. Instead, when economic and social factors underwent enormous changes that would have required certain responses from political leaders, it failed to produce these responses. One reason is of course the long-standing Confucian lack of interest in, even contempt for, commercial affairs and economic profit. But the divide between, on the one hand, an idealised form of government and organisation and a fast changing reality, on the other, further contributed to China’s stagnation during and after the Ming dynasty. Helplessly facing an administration largely in the hands of corrupt eunuchs of the inner court who despised the educated class, the Confucians at the end of the Ming turned their attention away from the present and future evolution of society, and inward into the past, towards a pedantic, dogmatic and reactionary view of ritual and correct behaviour.

During the Qing, Confucian scholars found themselves in an even more complicated dilemma. They had, just like the Qing emperors, reputiated the idealist philosophy initiated by Wang Yangming for stimulating the selfishness and moral corruption that brought down the dynasty.[xxv] However, they were also incapable of sharing the foreign Manchu rulers’ adoration of Song neo-Confucianism orthodoxy. And lastly, the Manchu emperors exerted rigorous control over scholarship in order to avoid the publication of anti-foreign writings as well as potentially revolutionary activities. Not many options seemed available. The way most scholars found out of this dilemma led them in fact further back, allt the way to the original Confucianism of the Zhou dynasty through Han dynasty sources, whereby they also introduced a rigorous methodology of textual criticism, the so-called “evidential research” (kaozheng xue 考证学). Unfortunately, this revival of the antiquity did not produce a revival of Chinese culture comparable to the revival enjoyed in the West following the rediscovery of classical texts during the renaissance. “Evidential research” involved a disapproval of speculation and demand for “hard facts”, which may sound as a form of scientific empiricism, but which gradually narrowed itself down to a rigorous and rather obscure textual analysis, such that many a group of scholars was “…so rigid in its view of the ancient commentaries of the Eastern Han as to preach that ‘the ancient teachings cannot be revised’ and one can only ‘maintain conformity to the family statutes of the Hans.’”[xxxvi] Seeking their own identity in the classical sources, the tendency of Ming-Qing Confucianism was towards a further reification of the Confucian practices, including, of course, education and its “ingrained” innovative force. Needless to say, the education system suffered in a comparable manner. It is therefore fair to say that from the Qing dynasty onwards, long before the civil service examination were abolished and Confucianism officially denounced in the twentieth century, Confucianism ceased to be a creative catalyst in Chinese educational practices.

www.bdcomcn.com

Nevertheless, education never lost its preponderant position in Chinese culture, and the twentieth century saw many reforms and experiments to construct a modern education system on a non-Confucian basis – with debatable results. Primary and secondary education in the PRC today is not very likely to stimulate independent thinking and creativity. The most important reason is that the education process revolves de facto around tests, in particular the gaokao or the college entrance examination, that, much as the imperial examinations of the past, is (or at least is held to be) the decisive factor for the quality of life that the person will enjoy. Therefore, parents have their children begin preparing for this examination at a very early stage. As one would expect, the one-child policy has merely exacerbated this tendency.

Lii Haibo, editor of Beijing Review, puts it in the following manner:

In primary and secondary schools throughout the country, examination-oriented education still prevails, although both parents and educators have realized it hurts students’ personalities, including the ability to think independently. In such an education system, students, including those prodigies, are trained to believe that their brains function mainly as a storage center. They are required to remember as much as they can. They are overloaded by heaps of homework. They don’t have enough time to play, sleep or do anything they like to do.

I once asked a senior high school boy, “Have you ever believed your brain to be a magic box?” “What do you mean?” he asked. “I mean you can be a great scientist like Einstein, if you use your head as a source of new ideas.” He told me that he didn’t need new ideas. All he wanted was to remember his teachers’ ideas and the textbooks. I understood that. Because the reality tells him that’s what an excellent student is all about. [xxxvii]

Another educator, Li Junjie, says, in a similar manner, that “…elementary and middle schools emphasize filling students’ brains with information, but ignore their moral, physical, and aesthetic dimensions. Teaching methods are directed toward pouring information into students, and not to the development of thinking skills, personal character, and creativity. In this model of teaching, studens are treated like empty cups, and not surprisingly many psychological problems have been reported. In short, ‘education for taking exams’ has become a barrier to the development of education in China.”[xxxviii] Considering this situation, especially with regard to China’s new role in the world order, it is not surprising that Chinese teachers and at least low-level authorities in China have displayed considerable interest in alternative pedagogies.[xxxix]

An interesting example of such pedagogies is the “Philosophy for Children” programme, which was first developed in the 1970s by Matthew Lipman, a professor of philosophy at Montclair State University in the United States. This programme aims at enhancing students’ critical and cognitive skills, creativity, concentration, sense of community, motivation for independent inquiry, and so on, by engaging them in philosophical discussion that focuses on students’ initiatives in asking questions and discussing topics in which they themselves take genuine interest.[xl] In a session of philosophy for children, the teacher is merely a facilitator. He or she does not tell the children what to talk about or what is true or not, but only leads the discussion and tries to make sure that it reaches some philosophical depth.

The programme has been enormously successful around the world and is active at some level everywhere in Europe, in North- and South-America and in many places in Asia. It has aroused quite some interest in those places where it has been introduced in the People’s Republic of China, and the methods have partly been adapted by Chinese teachers to be applied for teaching an even wider range of subjects.[xli] One of these places is Jiaozuo City in the province of Henan. Teachers in Jiaozuo got acquainted with the programme already in 1995 through exchanges with the University of Hawaii at Manoa, where philosophy for children has been practised since the 1980s. The Jiaozuo teachers saw in the programme an opportunity to improve education in China, and during the following years sought to apply it in their own work.

However, this turned out to be particularly difficult. In a normal philosophy for children class, everyone sits in a circle on the floor, facing each other, listening to and participating in the discussion. But in a class of at least sixty and sometimes up to eighty students, this is obviously impossible. A further problem was simply time. The teachers’ curriculum in China is overloaded with material to be covered, which made it difficult for them to find time to conduct open-ended discussions of topics for which the students would not be tested.[xlii]

But the teachers refused to give up. They thought of ways to adapt the programme to their circumstances. After several years of experimentation, they came up with the so-called “Elicitation Inquiry Style Teaching Method” (qifa tanjiu shi jiaoxue fa 启发探究式教学法). Instead of restricting the subject-matter to philosophy, teachers have been using this method in various subjects, mathematics, art, science, literature and others. The method encourages students to raise questions, to engage in small group discussions, and to think for themselves about possible solutions. In a manner similar to the Philosophy for Children programme, it challenges them to seek out clarification, reasons, implications, and assumptions, as well as to reflect on their own thinking.[xliii]

In this way, teachers found that they could adopt the inquisitive spirit of philosophy for children and at the same time work with large classes of sixty or more students. The experiment has enjoyed considerable success. In the year 2000, twenty-one schools in Jiaozuo participated in a trial of the method, and in the following year, both Jiaozuo’s Municipal Education Committee and its Institute of Education Research recommended that all schools in Jiaozuo adopt the Elicitation Inquiry method in their classrooms.[xliv] The fact that Chinese educators should be willing to adopt such an alien teaching method, one that Lipman developed on the basis of the pedagogic philosophy of the great American educator, John Dewey, might cause some people to raise an eyebrow. But considering the teaching methods suggested in classical Confucianism as discussed above, the main gist, or rather, “spirit”, of the method applied in the Philosophy for Children programme is remarkably familiar to the Chinese cultural tradition.

The psychological and pedagogical similarity between the methods of the Philosophy for Children program and the Confucian methods suggested in the Book of Rites and elsewhere are not only intriguing but also provide reasons for being hopeful. In contrast to the dominant teaching methods in the current Chinese education system, both emphasise that the teacher “lead but do not herd, motivate and do not discourage, initiate but do not proceed to the end.”

Moreover, an ideal facilitator in a session of Philosophy for Children ought to be a kind of Confucius, hinting and indicating without purporting to provide final answers, thus stimulating the students to reflect on the problem on their own. Apparently, some forms and aspects of Confucianism are now on the rise in China, and the ancient classics have been introduced to Chinese classrooms again after decades of banishment. One would hope that the creative-enhancing elements of these writings will gradually be revived and utilised. Further research on Confucian pedagogic theory and its applicability to the present could prove to be of immense value in this regard. By comparing and even fusing it with contemporary methods, such as those developed in the Philosophy for Children programme, one might be better able to extract some of its practical features. It would certainly be an interesting turn of events if the contemporary Chinese found the way to their ancient cultural heritage through a foreign teaching. One should, however, not forget that this foreign teaching is inspired by the educational philosophy of John Dewey, who, in turn, was much influenced by Chinese thought while he resided in China between 1919 and 1921. Perhaps the similarity is not that surprising after all.

IV. Concluding Remarks: Reflecting Without Learning?

The long-standing Confucian disposition to downplay economic issues has clearly been overcome in the PRC. In fact, such considerations receive more attention than anything else. The perceived need for China to “modernise”, meaning: attain technological superiority, is the main drive behind current economic reforms. Creativity is understood first and foremost as scientific and technological innovation. Whilst moral or character education in the People’s Republic has been promoted by all higher educational institutions in later years, the obstacles due to ideology and methodological codification are not easily overcome.[xlv]

First of all, the promoted values tend to be ones that seem to serve the interests of the authorities, which by now is obvious not only to teachers but also to students themselves. Secondly, the usual “inculcation” method for transmitting these values, using exemplary individuals and models of morality, such as Lei Feng, is so heavy handed that it “has rendered the public and even school children cynical.”[xliii] Thirdly, character education seems to be thought of as measures to bring about social stability in order to enhance creativity in the domains of science and technology. Consider the remarks of Li Lanqing, former Vice Premier and a major proponent of the current educational reforms in the PRC:

Schools are expected to provide an intellectual education while placing more emphasis on moral education and advancing physical and aesthetic education, as well as work skills and social practice so that these fields may become integrated and achieve balanced development for our students. Unless these issues are addressed, efforts to improve the overall quality of students will be affected, and education as a whole will fall short of the demands of the 21st century for economic, scientific and technological development and social progress.[xlvi]

With such an attitude to education, the Chinese authorities may be putting the cart before the horse. Confucius, while fully aware of all the practical conseqences of a harmonious society, understood that learning, education and morality must, in order to be effective, be practised for its own sake, and not merely for the sake of reaching some distant aims. To learn and practise what one has learnt is in itself a source of human joy, as he famously states in the opening passage of the Analects. [xlvii] A truly creative society that stimulates meaningful learning and innovation for its own sake and lays just as much emphasis on humanities and arts as on science and technology is sure to yield creative results in the latter fields from within. Critics of higher education policies in the People’s Republic have pointed out that the “overwhelming policy emphasis on higher education as an instrument of economic success tends to ignore the discourse of the ideas of modern university” and have cast serious doubts upon “the change of university as a social institution to university as a market-oriented enterprise”.[xlviii]

There is every reason to be wary of imposing such roles on the education system. In lectures given in 1933, the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset criticised the modern attitude to education as vocational specialisation. He deplored the inherent lack of passion in the Western educational system, whereby students are made learn things for which they did not feel any need. This, he said, has produced a culture of knowledge that does not concern us in our daily life any more, a culture of apathetic specialists, a culture utterly alienated from the knowledge of that which constitutes the good life: This culture, which does not have any root structure in man, a culture which does not spring from him spontaneously, lacks any native and indigenous values, this is something imposed, extrinsic, strange, foreign, an unintelligible, in short, it is unreal. Underneath this culture ⎯ received but not truly assimilated ⎯ man will remain intact as he was; that is to say, he will remain uncultured, a barbarian. When the process of knowing was shorter, more elemental, and more organic, it came closer to being felt by the common man who then assimilated it, recreated it, and revitalized it within himself. This explains the colossal paradox of these decades ⎯ that an enormous progress in terms of culture should have produced a man of the type we now have, a man indisputably more barbarous than was the man of a hundred years ago; and that this acculturation, this accumulation of culture, should produce ⎯ paradoxically but automatically ⎯ humanity’s return to barbarism.[xlix]

When these words were uttered, at the dawn of the arguably most gruesome and barbarous period in history during which fascist and ultranationalist ideologies exhibited their fierce contempt for human life and dignity in many parts of the world, Ortega y Gasset could hardly have realised just how true they were. The more alienated from their knowledge, the less the knowers are capable of critiquing the value of that knowledge, and are consequently more easily manipulable in the name of some ideology. “The solution,” Ortega y Gasset continues, does not consist of decreeing that one not study, but of a deep reform of that human activity called studying and, hence, of the student’s being. In order to achieve this, one must turn teaching completely around and say that primarily and fundamentally teaching is only the teaching of a need for the science and not the teaching of the science itself whose need the student does not feel.[l]

These words echo the position of John Dewey who never tired of pointing out the importance of integrating education and personal experience so that the students realise the purpose of learning and are then able to appropriate and apply that which they learn for the sake of contributing to the continuity of meaningful human living.[li] There is much to indicate that such mode of thinking is at most peripheral in the modern educational system in most of the industrialised world, and perhaps in particular in the People’s Republic. Vocational education and specialisation, of course, yield tangible results. After graduation from school, a student finds an occupation and produces, in most cases, measurable goods, at least in terms of income-tax. The fruits of character or moral education, of a developed sense or judgment, on the other hand, are intangible, immeasurable and thus statistically non-presentable. Moreover, it may very well be that keeping people technically specialised without a developed faculty of judgement serves certain purposes. Referring to what he calls “the banking concept of education,” in which students passively receive, memorise and repeat the “deposits” made by the teacher, Paolo Freire, in his classic Pedagogy of the Oppressed, argues that it is a dominant tendency among educators to regulate the way the world “enters into” the students. The teacher’s task is to organize a process which already occurs spontaneously, to “fill” the students by making deposits of information which he or she considers to constitute true knowledge. And since people “receive” the world as passive entities, education should make them more passive still, and adapt them to the world. The educated individual is the adapted person, because he or she is better “fit” for the world.

Translated into practice, this concept is well suited to the purposes of the oppressors, whose tranquility rests on how well people fit the world the oppressors have created, and how little they question it.[lii] Freire’s position, in fact, has much in common with the Confucian view of education as a process of creative socialisation and thus enhanced humanisation. Education is conceived as a mode of transformation in which persons perceive themselves as not merely being in a world, but with it and with others. They are re-creators and not merely spectators.[liii] Whilst the importance of tradition is certainly underscored in the Confucian philosophy, it mainly serves to guide the evolving personalities on their paths towards improving and integrating their environment. Confucianism is, or could be, a revolutionary philosophy, but it is revolutionary in that the revolution, the re-creation, is continuous and never comes to an end.

The talent required for such an ongoing task is far from being limited to scientists or other specialists, but should be held of every single member of society. A truly successful society must be based on the inherent value and meaningfulness of communal living as well as the willingness to continually and creatively adapt its individual fields to changing circumstances for the sake of a dynamic integration of its members. It is to this that creativity and innovation, whether in science, technology, economics or in the moral sphere, ought to be conducive. Otherwise, to speak with Confucius, it may very well degenerate into “reflection without learning” that, eventually, “results in peril”.

NOTES

[i] Probably the most influential Western theory of the imagination‘s free, i.e. disinterested, presentation of an external object to the inner subject is the one presented by Immanuel Kant in his Kritik der Urteilskraft . Kants Werke, vol. V (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1968), e.g. §1, 204.

[ii] Cf. David L. Hall and Roger T. Ames, who argue that the “classical Chinese are primarily acosmotic thinkers,” that is to say, “do not depend in the majority of their speculations upon either the notion that the totality of things (wan-wu 万物 or wan-you 万有 , “the ten thousand things”) has a radical beginning, or that these things constitute a single-ordered world.” Anticipating China. Thinking Through the Narratives of Chinese and Western Culture (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), 184.

[iii] Hall and Ames have suggested the notion of a contextual “focus-field” order to characterise Chinese ways to continually arrange and rearrange the immediate surroundings. Cf. Anticipating China , pp. 268.

[iv] See e.g. Tao Te Ching , transl. D.C. Lau, 2nd edition (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1989). Lau displays brilliance by producing a deliberately vague translation of this passage: “The way begets one; one begets two; two begets three; three begets the myriad creatures.” In their interesting translation, Ames and Hall are somewhat more radical: “Way-making (dao) gives rise to continuity, Continuity gives rise to difference, Difference gives rise to plurality, And plurality gives rise to the manifold of everything that is happening (wanwu).” Dao De Jing. Making This Life Significant , transl. Roger T. Ames and David L. Hall (New York: Ballantine Books, 2003).

[v] Zhuangzi . A Concordance to Chuang Tzu . Harvard-Yenching Institute Sinological Index Series. Supplement no. 20 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1956), 60/22/78.

[vi] Lunyu . A Concordance to the Analects of Confucius . Harvard-Yenching Institute Sinological Index Series. Supplement no. 16 (Taibei: Chinese Materials and Research Aids Service Center, Inc., 1966), 7.1.

[vii] Lunyu , 2.15.

[viii] Lunyu zhijie , 12.

[ix] Liji. A Concordance to the Liji . Ed. D.C. Lau and Chen Fong Ching (Hong Kong: Commercial Press, 1992), 32.28/146/26-7; Liji zhijie , annot. Ren Pingzhi (Hangzhou: Zhejiang wenyi chubanshe, 2000), 448.

[x] Lunyu , 2.11

[xi] Cf. Lin Li, “The Difficulties of Importing the Western Idea of Human Rights into China ⎯ A Jurisprudential Approach,” in Chinese Ethics in a Global Context. Moral Bases of Contemporary Societies , ed. Karl-Heinz Pohl and Anselm W. Müller (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 321.

[xii] The root of the word “appropriate” is the Latin proprius , meaning “one’s own.” In Confucian thought, it is the character yi 义 that expresses this complex thought of appropriateness. Cf. David L. Hall and Roger T. Ames, Thinking Through Confucius (Albany: State University of New York Press), 105.

[xiii] Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue. A Study in Moral Theory , 2nd ed. (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984), 222.

[xiv] The traditional English translation of junzi 君子 is “gentleman,” which, however, due to its unfortunate sexism, is unacceptable. As the characters for junzi imply, it signifies a lord, and is in fact synonymous with “lord” or “nobleman.” But it is a prescriptive term indicating the moral, cognitive and affective qualities that a true lord ought to possess. The junzi is thus Confucius’s consummate person, someone who has become noble and refined through self-cultivation and learning. In recent years, a multitude of translations have been proposed for this difficult term, none of which, in my opinion, catches the original junzi . I therefore leave it untranslated.

[xv] Cf. a fascinating discussion of the views of Zhou Zuoren 周作人 on tradition and its role in the New Culture Movement, a view that to my mind exemplifies the natural Chinese propensity to a creative adaptation of the emergent configuration of things. Xudong Zhang, “A Radical Hermeneutics of Chinese Literary Tradition: On Zhou Zuoren’s Zhongguo xinwenxue de yuanliu ”, in Classics and Interpretations: The Hermeneutic Traditions in Chinese Culture , ed. Ching-I Tu (New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 2000), 430ff.

[xvi] François Jullien, Detour and Access. Strategies of Meaning in China and Greece , trans. Sophie Hawkes (New York: Zone Books, 2000), 274.

[xvii] Chun-chieh Huang, Mencian Hermeneutics. A History of Interpretations in China (New Brunswick/London: Transaction Publishers, 2001), 258.

[xviii] Kai-wing Chow, On-cho Ng, and John B. Henderson, eds., Imagining Boundaries: Changing Confucian Doctrines, Texts, and Hermeneutics (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999).

[xix] As one might guess, such a creative ongoing interpretation and reinterpretation did not always take place in reality. In fact, the very notion of a single Confucian tradition with a stable set of ideas, values, and texts has itself been one of the strategies employed by Confucians, and today especially by scholars writing about the tradition and its historical development. In ancient times, for example in the Han and in the Song dynasties, such a strategy aimed at implementing institutionalisation, requiring codification of the teachings. The continuous hermeneutic transformation of the Confucian texts and doctrines generated “the constant need to canonize and legitimize texts and ideas, that is, to fix a boundary to establish a sense of stable authority. This imposed finality is, of course, fictive, and all canonical traditions are ephemeral.” Ibid, 2.

[xx] Lu Jiuyuan, Xiangshan yulu (Jinan: Shandong youyi chubanshe, 2000), 24. This resonates rather interestingly with the French philosopher’s Jacques Derrida’s insistence that “pure perception” does not exist: “we are written only as we write, by the agency within us which always keeps watch over perception.” Jacques Derrida, L’écriture et la différence (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1967), 335.

[xxi] Lunyu , 15.29.

[xxii] “Old parts, but a new whole,” The Economist , November 10th -16th 2007, 12.

[xxiii] “Old parts, but a new whole,”12.

[xxiv] “Old parts, but a new whole,”12.

[xxv] “Old parts, but a new whole,”12.

[xxvi] “Old parts, but a new whole,”12.

[xxvii] Lunyu , 7.8.

[xxviii] Lunyu , 1.15.

[xxix] Lunyu , 5.9.

[xxx] This association is stated quite explicitly in the Han dynasty lexicon Shuowen jiezi.

[xxxi] François Jullien, Detour and Access. Strategies of Meaning in China and Greece , trans. Sophie Hawkes (New York: Zone Books, 2000), 202.

[xxxii] “Records of Learning” (“Xueji” 学记 ) chapter of the Liji , 18.6-7/97/10-12 and 15-17.

[xxxiii] Following Ren Pingzhi in Liji zhijie (Hangzhou: Zhejiang wenyi chubanshe, 2000), 288.

[xxxiv] Jonathan Spence, The Search for Modern China , 2nd edition (New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999), 102f.

[xxxv] Zhu Weizheng, Coming Out of the Middle Ages , transl. Ruth Hayhoe (Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1990), 126.

[xxxvi] Lii Haibo, “Why Hasn’t China Reaped Scientific Nobel Prizes?”, Beijing Review 47:43 (2004), 48.

[xxxvii]Li Junjie, “America’s Philosophy for Children Teaching Method and the Development of Children’s Character”, Thinking. The Journal of the Philosophy for Children 17:1-2 (2004), 41.

[xxxviii] Cf. Michael Agelasto and Bob Adamson,. “Editors’ Conclusion ⎯ The State of Chinese Higher Education Today,” in Higher Education in Post-Mao China , ed. Michael Agelasto and Bob Adamson (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1998), 407ff.

[xxxix] For a concise overview giving a good indication of the “spirit” of the Philosophy for Children program, see Thomas E. Jackson, “Philosophy for Children Hawaiian Style ‘On Not Being in a Rush…’,” Thinking. The Journal of Philosophy for Children 17:1 & 2 (2004).

[xl] Cf. Andrew Colvin, “Expanding the Circle of Inquiry: Introducing Philosophy for Children in the People’s Republic of China,” Thinking. The Journal of Philosophy for Children 17:1 & 2 (2004), 38f

[xli] Cf. Colvin, 38.

[xlii] Colvin, 39.

[xliii] Colvin, 39.

[xliv] Wang Yongquan and Li Manli, “The Concept of General Education in Chinese Higher Education,” in Knowledge Across Cultures: A Contribution to Dialogue Among Civilizations, ed. Ruth Hayhoe and Julia Pan (Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong, 2001), 319.

[xlv] John N. Hawkins, Zhou Nanzhao, and Julie Lee, “China: Balancing the Collective and the Individual,” in Values Education for Dynamic Societies: Individualism or Collectivism , ed. William K. Cummings, Maria Teresa Tatto, and John Hawkins (Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong, 2001), 203.

[xlvi] Li Lanqing, Education for 1.3 Billion – Former Chinese Vice Premier Li Lanqing On 10 Years of Education Reform and Development (Beijing and Hong Kong: Foreign Language Teaching & Research Press and Pearson Education, 2005), 313. Italics mine.

[xlvii] Lunyu , 1.1.

[xlviii]Jushan Zhao and Junying Guo, “The Restructuring of China’s Higher Education: an experience for market economy and knowledge economy”, Educational Philosophy and Theory 34:2 (2002), 217.

[xlix] José Ortega y Gasset, Some Lessons in Metaphysics , trans. Mildred Adams (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1969), 23f.

[l] Ortega y Gasset, 25.

[li] Cf. John Dewey, Experience and Education (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1938), e.g. 25ff.; John Dewey, Democracy and Education. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education (New York: The Free Press, 1944), 1ff.

[lii] Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed , trans. Myra Bergman Ramon (New York: Continuum International, 1970), 76.

[liii] Freire, 75.

REFERENCES

Agelasto, Michael and Bob Adamson. “Editors’ Conclusion ⎯ The State of Chinese Higher Education Today.” In Higher Education in Post-Mao China, edited by Michael Agelasto and Bob Adamson. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1998.

Chow, Kai-wing, On-cho Ng, and John B. Henderson, eds. Imagining Boundaries. Changing Confucian Doctrines, Texts, and Hermeneutics. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999.

Colvin, Andrew. “Expanding the Circle of Inquiry: Introducing Philosophy for Children in the People’s Republic of China.” Thinking. The Journal of Philosophy for Children 17, nos.1 & 2 (2004): 37-39.

Dao De Jing. Making This Life Significant. Translated by Roger T. Ames and David L. Hall. New York: Ballantine Books, 2003.

Derrida, Jacques. L’écriture et la différence. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1967.

Dewey, John. Democracy and Education. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: The Free Press, 1944.

Dewey, John. Experience and Education. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1938.

Freire, Paolo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramon. New York: Continuum International, 1970.

Hall, David L. and Roger T. Ames. Anticipating China. Thinking Through the Narratives of Chinese and Western Culture. Albany: State University of New York, 1995.

Hall, David L. and Roger T. Ames. Thinking Trough Confucius. Albany: State University of New York, 1987.

Huang, Chun-chieh. Mencian Hermeneutics. A History of Interpretations in China. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2001.

Jackson, Thomas E. “Philosophy for Children Hawaiian Style ⎯ ‘On Not Being in a Rush…’.” Thinking. The Journal of Philosophy for Children 17, nos. 1 & 2 (2004): 4-8.

Jullien, François. Detour and Access. Strategies of Meaning in China and Greece. Translated by Sophie Hawkes. New York: Zone Books, 2000.

Kant, Immanuel. Kritik der Urteilskraft. Kants Werke, Vol V. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1968.

Li Junjie. “America’s Philosophy for Children Teaching Method and the Development of Children’s Character.” Translated by Andrew Colvin and Jinmei Yuan. Thinking. The Journal of Philosophy for Children 17, nos 1 & 2 (2004): 40-42.

Li Lanqing. Education For 1.3 Billion – Former Chinese Vice Premier Li Lanqing On 10 Years of Education Reform and Development. Beijing and Hong Kong: Foreign Language Teaching & Research Press and Pearson Education, 2005.

Lii Haibo. “Why Hasn’t China Reaped Scientific Nobel Prizes?” Beijing Review 47:43 (2004).

Liji 礼记. A Concordance to the Liji. Edited by D.C. Lau and Chen Fong Ching. Hong Kong: Commercial Press, 1992.

Liji zhijie 礼记直解. Annotated by Ren Pingzhi 任平直. Hangzhou: Zhejiang wenyi chubanshe, 2000.

Lin Li. “The Difficulties of Importing the Western Idea of Human Rights into China ⎯ A Jurisprudential Approach.” In Chinese Ethics in a Global Context. Moral Bases of 2002.

Lu Jiuyuan 陆九渊. Xiangshan yulu 象山语录. Jinan: Shandong youyi chubanshe, 2000.

Lunyu 论语. A Concordance to the Analects of Confucius. Harvard-Yenching Institute Sinological Index Series. Supplement no. 16. Taibei: Chinese Materials and Research Aids Service Center, Inc., 1966.

Lunyu zhijie 论语直解. Annotated by Zhang Weizhong 张卫中. Hangzhou: Zhejiang wenyi chubanshe, 1997.Tao Te Ching. Translated by D.C. Lau. 2nd edition. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1989.

MacIntyre, Alasdair. After Virtue. A Study in Moral Theory. 2nd edition. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984.

“Old parts, but a new whole”. The Economist, November 10th 2007.

Ortega y Gasset, José. Some Lessons in Metaphysics. Translated by Mildred Adams. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1969.

Spence, Jonathan. The Search for Modern China. 2nd edition. New York and London: W.W.Norton & Company, 1999.

Wang Yongquan and Li Manli. “The Concept of General Education in Chinese Higher Education.” In Knowledge Across Cultures: A Contribution to Dialogue Among Civilizations, edited by Ruth Hayhoe and Julia Pan. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong, 2001.

Zhang, Xudong, “A Radical Hermeneutics of Chinese Literary Tradition: On Zhou Zuoren’s Zhongguo xinwenxue de yuanliu”.In Classics and Interpretations: The Hermeneutic Traditions in Chinese Culture, edited by Ching-I Tu. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 2000.

Zhao, Jushan and Junying Guo. “The Restructuring of China’s Higher Education: an experience for market economy and knowledge economy.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 34:2 (2002).

Zhu Weizheng. Coming Out of the Middle Ages. Translated and edited by Ruth Hayhoe. Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1990.

Zhuangzi 庄子. A Concordance to Chuang Tzu. Harvard-Yenching Institute Sinological Index Series. Supplement no. 20. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1956.

Previously published in: Fan Hong, Jörn-Carsten Gottwald (Eds.) – The Irish Asia Strategy and Its China Relations 1999-2009. Amsterdam, 2010.

Introduction

Introduction