Chapter 11: Comparing Irish And Chinese Politics Of Regulation ~ The Irish Asia Strategy And Its China Relations

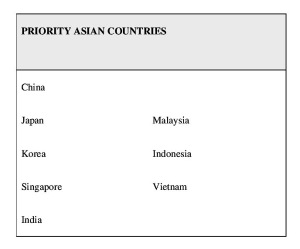

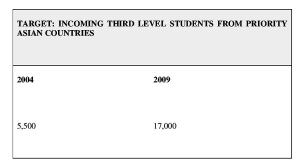

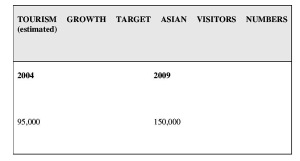

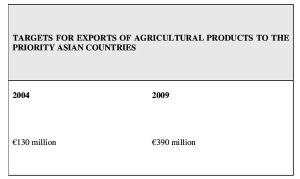

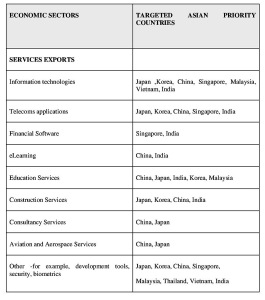

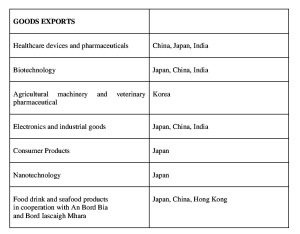

In its Asia Strategy, the Irish Government calls for closer cooperation between Europe and Asia and a higher profile of Irish business, society and politics in this core region of the global economy. While the focus in general rests on trade and investment, there is one area where Ireland as Europe’s Celtic Tiger has much to share with its distant partners: regulatory reform and innovation as a key driver for economic modernisation and competitiveness. From an academic perspective, the analysis of regulatory regimes, states and capitalisms has enjoyed years of impressive development. While some have focused on a better understanding of the evolution of regulation and their impact on political systems or the world economy, a second stream in regulation research seeks criteria for an evaluation of existing regulation and the promotion of better regulation. Case studies from different jurisdictions are frequently used to highlight practical and theoretical issues. In this paper, the experience of two states experiencing impressive rates of economic growth but exhibiting contrasting political systems are analysed to isolate areas of convergence in regulatory development. China and Ireland are of vastly different size but the Middle Kingdom dwarfs most other states. The comparison is, however, made more plausible by Ireland’s need to accommodate EU regulatory strictures and China’s adjustment to an open market economy. Further, though small, Ireland does not operate in an international political vacuum. Like other western democracies that are “open, integrated, and rule-based, with wide and deep political foundations”[i] and, as such, represents a typical liberal democracy. Nevertheless, to acknowledge the clear differences between the cases chosen, the paper concentrates on aspects of the Irish experience that might signal useful insights for China in the areas of transparency, innovation and competition.

In its Asia Strategy, the Irish Government calls for closer cooperation between Europe and Asia and a higher profile of Irish business, society and politics in this core region of the global economy. While the focus in general rests on trade and investment, there is one area where Ireland as Europe’s Celtic Tiger has much to share with its distant partners: regulatory reform and innovation as a key driver for economic modernisation and competitiveness. From an academic perspective, the analysis of regulatory regimes, states and capitalisms has enjoyed years of impressive development. While some have focused on a better understanding of the evolution of regulation and their impact on political systems or the world economy, a second stream in regulation research seeks criteria for an evaluation of existing regulation and the promotion of better regulation. Case studies from different jurisdictions are frequently used to highlight practical and theoretical issues. In this paper, the experience of two states experiencing impressive rates of economic growth but exhibiting contrasting political systems are analysed to isolate areas of convergence in regulatory development. China and Ireland are of vastly different size but the Middle Kingdom dwarfs most other states. The comparison is, however, made more plausible by Ireland’s need to accommodate EU regulatory strictures and China’s adjustment to an open market economy. Further, though small, Ireland does not operate in an international political vacuum. Like other western democracies that are “open, integrated, and rule-based, with wide and deep political foundations”[i] and, as such, represents a typical liberal democracy. Nevertheless, to acknowledge the clear differences between the cases chosen, the paper concentrates on aspects of the Irish experience that might signal useful insights for China in the areas of transparency, innovation and competition.

Thirty years after the Chinese leadership initiated the policies of reform and opening up to the outside world, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is a remarkable economic success story and an increasingly opaque puzzle for academic research. Its ‘Socialism with Chinese Chracteristics’ has seen average annual growth rates of more than 10% since 1980. By World Bank standards, China in 2006 was the fourth largest economy in the world, a major trading nation and holder of the largest foreign exchange reserves. At the same time, its ‘Socialist Market Economy’ exhibits fundamentally contradictory features: while there are comparatively free markets in some sectors of the economy that tempt observers to compare today’s China with the Manchester of the early 19th century, private property rights have only recently found their way into the constitution and are still subject to the interpretation and protection by a judiciary under direct control of the political leadership. China’s rule by law – not to confuse with the concept of rule of law – is executed by courts and bureaucracies under direct control of the Leninist apparatus of the Communist Party of China, which, according to the constitution, leads all Chinese political institutions and exerts the democratic centralism as part of the dictatorship of the people.

The interdependence of social orders that links the existence of a market order with a pluralist democratic system that guarantees rule of law points at an implicit instability of China’s political and social order. But, while doomsayers had their fair share of academic and public interest in the 1990s, the survival of CCP rule in spite of fundamental changes in the economic and social system requires further analysis. There is no consensus among China watchers on the nature of its political order. Characterisations include soft authoritarian, adaptive authoritarian and neo-consociational. Similary, opinion on the direction of its future development ranges from enhanced state capacity stabilising party rule to decreased state capacity destablising the CCP. It is obvious nevertheless that somehow China’s hybrid political and economic order is a survivor.

Part of an explanation how exactly the Chinese leadership has managed to maintain political control and economic dominance in an increasingly pluralist social and market economic environment lies in its proven track record in institutional learning and innovation. At the same time, a global trend towards the introduction of new forms of governance, particularly of quasi-independent regulatory bodies, is recalibrating the traditional relationship between governments, societies and markets in well-established OECD countries as well as in emerging markets.

While the rise of the regulatory state, the post-regulatory state and regulatory capitalism has led to an intensive debate about efficiency and legitimacy, its implications for non-democratic states with emerging market orders has been painfully neglected.[ii] The global trend to redefine the relationship between governments and markets, between state and non-state actors in the area of economic activity, however, has changed the perception of social orders and has a direct impact on the institutional and policy change of states in an interdependent world.

11.1 The Rise of Regulatory Capitalism in China

Property rights, the rule of law and a stable institutional framework are usually taken as a sine qua non for a functioning market economy. In the PRC, nearly thirty years after the leadership embarked on an encompassing programme of economic reform, none of these are fully in place.[iii] In rural areas in particular, privatization of land is still resisted 30 years after Deng Xiaoping ordered the “household responsibility system” giving farmers leaseholders’ rights including that of keeping and selling surpluses. The exact impact of the transformation from a socialist state à la Chinoise towards a modern and open authoritarian market economy still is one of the most controversial issues in current China research.[iv] Fundamental differences persist in the perception of China’s political system after reform with regard to the issue of democratisation. But even in analysing individual aspects of social life and various sectors of the Chinese economy, a diffuse set of potentially incompatible institutional arrangements emerge. The fundamental issue of China’s political and economic order is far from resolved.

At the same time, research on established western market democracies has brought forward a better understanding of path dependencies within national and regional institutional frameworks, creating a great ‘variety of capitalisms’.[v] Further, a major side effect of globalisation seems to be a universal trend from traditional government to modern governance.[vi]

Admittedly, a clear and broadly accepted definition of governance is still open to consideration. The debate has, however, been instrumental in shedding light on the relationship between ‘steering’ and ‘rowing’ in modern societies, i.e. between decision-making and socio-economic activities. Interestingly enough, while China-watchers still discuss the impact of marketisation on China’s democratisation, the debate on the rise of the regulatory state in the age of governance in established Western market democracies questions exactly the compatibility of

participatory decision-making in representative democracies with efficient market oriented regulation.[vii]

11.2 The Rise of the Regulatory State and the Evolution of Market Economies

After the breakdown of the socialist states in Eastern Europe, social scientists engaged in an extensive debate on the unforeseen implosion of the main alternative to Western democratic market economies,[viii] provoking the notion of the ‘end of history’.[ix] Mankind was rushing towards market economy and pluralist democracy based on certain prerequisites – rule of law, active guarantees of competitive markets, stable macro-economic framework. A market economy seemed to depend on the existence of democratic political institutions. For neo-institutionalist theories in economics and political science, the significance of property rights, relational contracts and trust for economic and social development provided further support of the presumed close linkage between market economies and a representative pluralist democracy. The case was proven in the simultaneous restructuring of the economic and the political order in most socialist countries after 1989 – with the one astonishing exemption of the People’s Republic of China.

Given the breathtaking speed of economic and social developments in China, the dominant theoretical approaches characterise the Chinese political order as unstable because of a dissonance between the deepening and broadening of economic reforms and its nominal ‘socialism’. Indeed, there is ample empirical evidence for the growing pressure on China’s political order to adapt to the new unleashed forces of market activities. But while series of administrative, inner-party and governmental[x] reforms confirmed the need for restructuring the political order, the CCP manages to preserve a basically unchallenged dominance[xi] over political processes and institutions.

Confronting this theoretical and empirical puzzle, some observers still perceived a slow transformation of China’s political system,[xii] while others claimed somewhat paradoxically that the deepening and broadening of market oriented economic reforms had not only left basic mechanisms and instruments of political control by the CCP in place, but that overall the CCP seems to have improved its capacity to dominate the political order. In different words, the Leninist party system has not only shown a surprising resourcefulness for institutional and organisational innovation,[xiii] but seems to come out of the great transformation as a clear benefactor of change – and not as its victim.

The fact, that nearly thirty years of market oriented reforms in China have not led to the expected downfall of one party rule, but might even have contributed to an increase in state capacity under the leadership of the CCP, is one the must fundamental puzzles in current politics and academic research. It raises significant questions: First, whether the productive co-existence of a Leninist party-state with an evolving market order is sui generis and, if so, what are its main characteristics. Secondly, how can one best explain the stabilising impact of market reforms on the Chinese polity?

11.3 Regulation, Governance and Capitalism

Analysing China’s Socialist Market Economy raises the fundamental issue of the concept and role of the state. In traditional i.e. ‘Western’ perspective, the basic notion of the modern (nation-) state and its role in economic activities usually refers to the political order in Europe after the devastating religious wars in the first half of the 17th century, the emerging political order after the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 established the notion of a sovereign state, governed by an administrative apparatus, with unchallenged control of clearly defined territory, within which the sole legitimate use of force rested with the ruler.[xiv] This context of the modern state formed the basis for fundamental legal and political theories concerning government, society and market activities. In the second half of the 20th century, several developments led to a fundamental revision of this early concept: the politics of European integration jarred with the concept on sovereign states preserving their independence and relative power; then, all the processes usually subsumed under the term ‘globalisation’ undermined the capacities of modern governments to pursue their policies independent from the interest of other governments and an increasing number of non-state actors,[xv] particularly enterprises and civic organisations. Finally, the rise of East Asian economies from developmental to industrialist status re-invigorated the debate concerning the different attitudes of public-private interactions, replacing the traditional dualistic perception of ‘the state’ and ‘the society’ or ‘the economy’ to a rather inclusive perception of close-knit network comprising bureaucrats, parliamentarians, NGOs and enterprises.[xvi] These led to new complex forms of rule-making by national law-making, trans-national standard setting, inter- and intra-national consultations and negotiations or simply a privatisation of rule-making through increased reliance on non-majoritarian forms of decision-making.[xvii]

Diffuse as the literature on governance remains, at its core are new forms, mechanisms and ideals about the development, implementation and revision of sector-specific policies. This paper looks at these issues through the narrow prism of ‘regulation’ and the ‘regulatory state’ though it draws on the macro-scientific debate on governance in sociology, economics and politics.[xviii] The regulatory state is interpreted here as a specific form of market creation and market correction, a political act to shape the relationship between state and private actors.

Following the positive theory of regulation as introduced by Stigler and Peltzman[xix] and combining it with an actor centred institutionalism in the Cologne tradition,[xx] the paper interprets regulation as the formulation, implementation and revision of specific rules for narrowly defined policy fields or aspects of social activity. Regulation in this sense is the outcome of interactions between individual or collective actors trying to realise their preferences within a dynamic institutional framework.

Following North, the paper distinguishes between actors as “players of the game” and institutions as “rules of the game”. Social groups – and sometimes individual actors–simultaneously strive to realise their preferences and to modify the institutional framework to their advantage.[xxi] Thus, regulation by definition is dynamic and characterised by a flexible approach towards problem solving including and combining various norms and mechanisms of governance. Regulation in this understanding goes beyond the traditional centrality of state law

as it combines state law with other forms of formal and informal contracts. Especially in the area of financial markets, institutional change is fast and competition between interest groups vying for profits is sharp, often leading to a race between market intervention, business crisis and re-regulation. This is especially true for dynamic multi-level polity entities that undergo a process of institutional change – such as the PRC or the European Union.

In this context, it seems necessary to merge research on China’s new political and economic order with these new approaches in regulation and capitalist theories and turn the attention from ‘Government’ to ‘Governance’.[xxii] But, while the concept of ‘governance’ has proved to be an effective approach to integrate social and economic non-hierarchical forms of decision-making into the classical analysis of the workings of the state apparatus or political systems, the paper acknowledges that it suffers from a lack of clear cut assumptions and workable definitions. Only too often the analysis of Chinese governance turned out to be a simple combination of analysing the CCP’s rule with various trends in economic development. Besides, work on economic policies in established market economies has shown a broad diversity of arrangements within existing capitalisms, varying from sector to sector and sometimes even within.[xxiii] The paper accepts McNally’s[xxiv] interpretation of China’s rise as the evolution of a capitalist socio-economic order and seeks to develop a new analytical framework.[xxv]

If different organisational arrangements within capitalist orders are common, then the co-existence of different regulatory regimes within a political economy loses its uniqueness. Instead, the distinctive element of current varieties of capitalism is the incorporation of independent agencies.[xxvi] The global and sectoral diffusion of this post welfare state form of policy making clearly contradicts early claims of a neo-liberal global marketisation. Quite to the contrary, the opening up of national sectors of the economy to foreign competition and the introduction of global standards have led to a worldwide wave of re-regulation – introducing new ideas of regulation, new rules, new regulatory organisations and new instruments. As a by-product, technocratic expertise has gained an important stake in the global search for optimal regulation. Real markets seem to be in a constant need for rule-making, implementation and revision of rules. Thus, formal and informal institutions set the incentives for rational actors pursuing their interests to compete for maximum gains within the existing framework and for changing the institutions to their best advantage.

The ongoing process for regulatory innovation is inseparably linked with competition and transparency.

11.4 Regulation, Compettion and Institutional Change

Each political system must address both internal and external pressures within the context of a competitive world economy in which extremely mobile investment is a key driver. Since the success of the Asian miracle economies, starting with Japan in the 1960s, openness for the inflow of capital, know-how and technology has become the dominant paradigm for the pursuit of economic modernisation. Today, emerging markets compete with the well-established OECD countries stimulating an exponential growth in worldwide capital flows. The question now is not whether to open up an economy to global markets but how to best organise the regulatory framework for domestic and foreign actors for economic activity.

The process of liberalisation must not be misinterpreted as an ongoing de-regulation.[xxvii] Substantial political and economic research provides ample evidence that the creation of new markets requires a combination of re-regulation and de-regulation.[xxviii] Regulatory reform has, therefore, become an integral part of macro-economic policies. Due to the dynamic nature of not only capital but most global markets, regulatory frameworks can be perceived as permanently in the making. The issue of adopting, re-organising, improving existing regulation requires a high degree of state or political capacity. Crisis management, day-to-day adaption and innovative relaunching of regulatory regimes is a fundamental task for all economies which deal with multinational enterprises.

The importance of sound decision-making and successful political management of regulatory reform is nowhere clearer than in countries which embark on a course of radical modernisation. A well-documented case for this point is Ireland, where the industrial strategy chosen in the 1960s stressed infrastructural investment, tax concessions and other incentives to attract foreign direct investment and integrate these into a liberal trading regime. The state deliberately opted for a policy change, turning to global markets and using substantial subsidies from the

EU for improvements in infrastructure and education. This process was clearly government-driven, notwithstanding the crucial role of US investment and EU transfers. This role of the Irish political leadership reflects Porter’s model of comparative advantage with the state acting as a catalyst to higher levels of competitive performance by companies, mediating between domestic social and economic interests and assuring a supportive business environment.[xxix] A reputation for good governance is, for Ireland, a comparative advantage though this might be offset if too intense a regulatory regime imposed higher compliance costs on firms operating there than in rival jurisdictions.[xxx] The balance between the governance benefits and compliance costs is hard to quantify as is that between internal and external pressures but each is discussed here with reference to three recurring themes in the discourse on regulation – transparency, competition and innovation.

Transparency, innovation, and competition all have an internal as well as an external dimension and they are all interdependent. In this paper, it is argued that it is especially the area where these three issues are interconnected that proves characteristic for the working or failure of regulation. It is important to keep in mind the crucial role of public actors, i.e. the government, business and consumer organisation and regulatory agencies, in shaping the interconnectedness of transparency, innovation and competition.

11.4.1 Transparency

Transparency has become a guiding concept in the lexicon of governance though frequently honoured more in the breach than in the observance. In relation to regulation, transparency is thought to offer citizens, companies and other political actors clear lines of accountability.[xxxi]

Accountability then is crucial requirement for the preservation of legitimacy and the possibility of effective political management of regulatory reform. Similarly, for relevant external actors, particularly potential investors and intermediaries, transparency is the prerequisite for rational decision-making. In addition, it equates to reassurance that competition is fair, assets safe and profits recoverable. Investors should be able to take a reliable institutional framework ensuring rule of law and enforcement as a given. Thus, internally, transparency’s foremost importance is political while externally it is economic.

Transparency is not among the traditional virtues of either public bureaucracies or business. For civil servants, personal anonymity and ministerial responsibility are prized characteristics that the public sector reforms, captured by the term ‘new public management’, have only recently challenged. For senior politicians also, the idea of transparency is a threat to the promises, bargains and compromises that are their stock in trade particularly when dealing with domestic entrepreneurs and potential inward investors. From a business perspective, the balance between a minimum of transparency to be attractive for investors and customers and the maximum of protection of know-how and technology has always been uneasy. Even the highly sophisticated networks of investment bankers, rating-agencies, free media and governmental and non-governmental regulatory bodies have failed to disclose the manipulations of ENRON and WorldCom. As the US sub-prime mortgage crisis demonstrates, modern financial products have become so complex and, thereby, non-transparent that even the top management of the big global banks seems unable to understand their own dealings.

In the case of Ireland, the political, administrative and business elites have developed a close working relationship. While this might be beneficial for internal transparency, where a close network of local elites allow a Celtic version of London’s famous ‘Gentlemanly Capitalism’,[xxxii] its impact on non-domestic actors is problematic. Informal networks tend to shape official regulation according to local interest, traditions and loyalties. Non-members of these networks encounter a gap between formal and informal rules and regulation. Closing the gap increases the costs and the risks of their activities. Thus, the introduction of autonomous statutory regulators and the ongoing adoption of global standards and regulatory practices enhance the level of transparency in relation to the general business environment and particularly levels of competition.

11.4.2 Competition

Competition itself is also used as an axiom. Indeed, among regulators, the benefits of competition for the maximal use of resources and the process of wealth creation are unchallenged. For politicians, interest groups and even citizens the benefits are not always so clear especially in their constituency, in the short term or in the faces of personal readjustments. The main thrust of competition policy in most political systems is the removal of barriers associated with restrictive trade practices, monopolies and access to financial and other resources. For inward investors, the key is often consistency in the application of policy when applied to non-local enterprises. In Ireland, the combination of a generic regulator for competition and a number of sectoral regulators has ensured that almost all business areas are covered. Nevertheless, competition may be compromised by regulatory capture, with the interests of potential competitors being crowded out by the vested interests of the existing incumbents.

An interesting case study in competition in Ireland is offered by the development of single electricity market spanning the two jurisdictions on the island – the Republic and Northern Ireland. Energy is important for an island with little natural resource and which is at the end of Europe’s gas supply lines. Electricity prices for businesses are significantly higher than elsewhere in the EU. Central planners, who forecast demand and influenced investment decisions, have made way for the market. The dominant player on the island, the Republic’s Electricity Supply Board (ESB), has devested 1500 MW worth of plant as part of the reform. New suppliers or distributors, as distinct from the generating companies, have emerged. The crucial test for long-term investors, in what remains a small market, is whether the Republic’s government can separate its role as owner of ESB from that of the statutorily independent regulator when politically sensitive decisions have to be made.

11.4.3 Innovation

Innovation is regarded as a major driver of the economy and so a great deal of the thrust of regulation is aimed at encouraging it. Public policy is designed to facilitate the introduction of new goods, methods of production, market opportunities, sources of supply or, though less often recognised, new forms of business organisation by indigenous companies. Potential investors, particularly from outside, will look to regulators to offer protection to their intellectual property, research investment and license income. The area of innovation is particularly sensitive for regulators in part because of the necessary levels of confidentiality but also because R&D needs to frequently challenge existing standards. In this context, EU business complains that the US regulates in the R&D function with a much lighter touch in many areas. In Ireland, making sure industry complies with regulations is tempered by the need to assist firms manage, protect and extract full value from their intellectual assets to strengthen their competitiveness. Thus, both critics and admirers use the term “light touch” to describe Irish regulation.

There is a presumed tension between regulation and innovation which is summarised in the maxim that government-backed rules undermine creativity. This is again based on the idea that the market rewards new ideas and business solutions. Innovation has, however, always depended upon certain kinds of regulation. In Ireland, the authorities has tried to use regulation to encourage indigenous companies, especially SMEs, by countering both the resistance of existing suppliers to competition and the propensity to anticompetitive practices. While ensuring that innovators comply with regulations, Irish governments seek to help firms gain competitive advantage. Entrepreneurs complain that regulation damages innovation by making it harder to cut costs or organise more flexibly. In this respect, overcoming the impact of regulation may itself be a fillip to innovation.

The ability of the Irish authorities to facilitate innovation is substantially narrowed in areas of high standardisation at EU level as is increasingly true in the area of financial services. In such areas, experimentation and the development of new techniques is inhibited and, critics allege, a “race to the bottom” is encouraged by so-called “jurisdictional competition”.[xxxiii] The Irish experience is that, for the most part, EU member state financial regulators cooperate extensively, regularly share information on best practices and keep up both formal and informal dialogues and technical consultations. Ireland has sought to reassure investors by cost justified regulation and while encouraging innovative financial products. This search for equilibrium speaks to the issues of intersecting pressures discussed below. It is important to note, however, that the Irish principles-based regulatory regime in this area is vulnerable to pressures on it from events in other jurisdictions with a similar approach. Thus, for example, the Northern Rock crisis in the UK in 2007/8 increased calls for a pan-European regulator operating a system closer to the tightly specified American model that inhibits innovation.

The relationship between innovation and regulation is complex but external investors generally seek assurance that their innovations and innovatory capacity are protected. Innovators may look elsewhere to develop new projects if they have doubts about the regulatory environment. On the other hand, Ireland is party to EU regulations[xxxiv] on the abuse of dominance, clearly a danger associated with large multinational companies. Further, governments themselves cannot force innovation particularly through regulation. In relation to external interests, the Irish government may seek to influence innovation by encouraging industrial clustering or proximity to educational facilities using regulation but these constraints are never used to inhibit investment. The regulatory burden is seldom severe or costly to maintain and the right to innovate is protected mostly by forms of regulation that hinder power to control new initiatives.

11.4.4 Intersection

This paper proposes that the significant analytical areas for understanding regulation in Ireland and China can best be identified by the intersection of transparency, competition and innovation. It suggests that much of the political tension that surrounds the area of regulation in dialogue between China and its trading partners, particularly in the EU, arises from the conflicting imperatives of transparency, competition and innovation. Further, the intersecting areas are those most likely to present challenges for China as its developmental model changes. Again, the paper suggests that the Irish growth strategy based on productivity and innovation rather than using more labour and other resources more intensely, which informs much regulatory reform, may be illuminating for China.

Accession to the WTO has highlighted the need for a more rigorous approach to regulation in China, especially to comply with the Agreement on Traded-Related Aspect of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs). In the early 1990s, the low cost/low skill developmental model was much to China’s advantage in competitive terms. For example, the so-called “China price” was the unbeatable sourcing benchmark for American, Japanese and European retailers. The regulatory framework could afford to be weak. Since the mid-1990s, however, competition from other Asian economies has suggested the need to go beyond low cost by increased efficiency. Issues of pollution, energy costs, trade imbalances and skills shortages now point to the need for a new developmental model in which quality standards and technological transparency and innovation become clearer. Foreign companies for whom it is an asset to be protected and rent extracted own the majority of IPR in China.[xxxv]

Some observers have criticised the “regulation-lite” policies of the Irish financial services regulator. The Irish principle-based and permissive policy illustrates the tension between competitiveness and transparency. In capital markets, for example, there is a significant enforcement gap between Irish and some foreign practice especially other common law jurisdictions such as the US, Canada and Australia. In broad terms, the dilemma faced by Ireland is between attracting trading volume and reducing the cost of capital. The regulatory and disclosure environment in Ireland reduces compliance costs and the low levels of enforcement mean increased business but both features risk greater insider trading and market manipulation. In China, however, the state’s less transparent political structure might mean that stricter enforcement will be needed to engender greater trust and confidence and lead to higher capital valuation.

While emphasizing good governance, the [current Chinese] reform [of the civil service] cannot achieve the ultimate objectives of “good governance” practices because the administration is not sufficiently insulated from political influence.[xxxvi]

Further, despite the opening of foreign stock exchange offices in China, The Economist reports that Chinese regulators are “pressing domestic companies to list at home”.[xxxvii] If China is to adopt a developmental model that calls for increased local generation of IPR then the reassurance that foreign companies expect from a transparent regulatory system may need to be matched by some protection for Chinese innovation in R&D.[xxxviii] There will be increased demands internally for support for indigenous companies, especially in the non-state SME sector. The central and provincial governments are already looking at the South Korean and Japanese models but the Irish experience may be more relevant because of Ireland’s high dependence on foreign research funding. This has, in recent years, caused the Irish government to increase very significantly its support for scientific research in key industrial sectors and in the Republic’s universities.

Similarly, as China passes out of a period in which imitation was a viable strategy for local enterprises, regulations governing barriers to internal market competition that currently inhibit the free movement of labour and goods to protect local enterprises will have to be removed. In the short term, this may lead to the relocation to less expensive parts of China of relatively low-tech, labour-intensive, less time sensitive industries but these will be replaced by research and development lead enterprises. The need to make regulations transparent and consistent will reduce the ability to shelter local industries or impose differential cost of compliance. In Ireland, a constant feature of the business interest groups’ commentary on regulation is a comparison of the cost of “red tape” in the various member states of the EU. Naturally, each jurisdiction claims that others are less strict in their application of regulations. In some areas, especially food, medical devices and pharmaceuticals, where the US market is crucial both China and Ireland have had to conform increasingly to American regulatory standards and costs.

China not only needs continued access to the global capitalist system; it also wants the protections that the system’s rules and institutions provide. The WTO’s multilateral trade principles and dispute-settlement mechanisms… offer China tools to defend against the threats of discrimination and protectionism that rising economic powers often confront… Chinese leaders recognize these advantages.[xxxix]

The overlapping imperatives of transparency and competition have recently been highlighted by clashes between China and its trading partners. The achievement of market economy status is a goal for China that has clear implications for the development of regulation. China is the focus of much suspicion by foreign governments especially of countries with a high level of dependence on exporting. Technical and non-tariff barriers to exports, especially in textiles and light industries, are resented by the Chinese authorities which retaliate through what their critics allege are selective use of regulatory measures. These tensions are likely to be exacerbated by the trend, familiar to Ireland, for exports with a high domestic content, such as toys, to become less significant than those with more imported components such as electronics. Ireland has for the most part avoided trade issues becoming political by granting statutory autonomy to its regulators, though clearly government departments do retain both informal and legal powers to influence them. Like China, Ireland retains the right to direct regulators to have regard to broad public policy objectives but it does not seek to protect “key Chinese brands” or prevent acquisitions involving “economic security”.

The scale differences between Ireland and China in size, population and domestic natural resources are vast. For Chinese companies, their home market is huge and provides the basis making local brands global. Many are expanding sales and production internationally and are leveraging rapid growth at home to invest abroad. Ironically, the experience of operating in an emerging economy may make Irish and Chinese managers more adaptable and resilient abroad. Competition from major international companies in their home markets, which puts pressure on local dominance, also exposes them to best international practice and encourages them to seek expansion abroad. In some cases, the proximity of large international companies has helped Irish firms to develop new and better business models that facilitate expansion abroad. In such circumstance, both Irish and Chinese entrepreneurs have adopted a more aggressive attitude to outward investment and to regulation abroad. Innovatory excellence at home can be exploited abroad through acquisitions, joint ventures and direct investment only in a permissive transparent regulatory framework. This is particularly true for companies seeking a global reach in narrow product or service categories.

China may well feel that the achievement of market status has more to do with politics than economics but trade frictions will continue if regulators are seen to privilege state owned enterprises. In Ireland the government has also found it difficult to disengage from former state companies and the electorate has similarly been reluctant to accept some market decisions as outside political influence. Corruption and local protectionism at the provincial levels in china are also an inhibition to effective regulation that has resonances in Ireland. Though the scale is

different, the impact of local officials, national civil servants and politicians eliding the public interest with that of particular enterprises was at the core of Ireland’s corruption scandal associated with the beef industry. At root, this and other incidences of corruption and localism arise from a failure on the part of politicians and regulation enforcers to administer with an “arm’s length relationship”[xl]. In Ireland, reform has involved increased resources and training for enforcement officials, tribunals of enquiry and a change of public attitude regarding the economic and social impact of lax regulatory enforcement.[xli]

11.5 Conclusion

President Hu Jintao has made the promotion of good governance a key political priority and advocated a drive to build a “harmonious society”. The fate of the Chinese Communist Party and its version of socialism are at stake. He has rejected Western-style political reforms, warning that they would lead China down a “blind alley” but has identified prosperity and engagement with the global economy and something else as the sine qua non of the Party’s survival. Ironically, many of the same regulatory instruments that in liberal democracies have seemed necessary to sustain elected government in the face of a neo-liberal critique of their function are now central to the longevity of communism.

Any comparison of the Chinese and Irish experience of adapting to integration in the world economy must acknowledge the contrasting geopolitical realities of a global power and a small EU member state. The PRC is in a position to resist changes that are judged by its leaders as “interference” in its domestic priorities, the most important of which is preserving the current order in the face of rapid and intense social change. On the other hand, both China and Ireland have accepted the constraints of the major established institutions of western capitalism. Ireland has also faced the consequences of openness with the loss of some industries that were dependent on protectionist policies and the decline of others. China has been less willing to do this and still displays neo-mercantilist approaches to trade by, for instance, keeping its currency artificially low to raise its trade surplus and lower its costs of production relative to its competitors.

NOTES

[i] G. John Ikenberry, “The Rise of China and the Future of the West: Can the Liberal System Survive?”, Foreign Affairs , January/February 2008.

[ii] Important exemptions: Christopher McNally (2007), China’s Emerging Political Economy. London:Routledge; Sebastian Heilmann (2005), Das politische Sytem der Volksrepublik China. Wisebaden:WV; Yang Dali (2005), The Chinese Leviathan, New York: CUP.

[iii] A law guaranteeing private property rights passed the NPC at the time of writing this paper. Although this might legally establish individual property rights, doubts on the enforcement of these rights remained well in place. See ‘Caught between right and left, town and country’ in The Economist, 8th March 2007.

[iv] See Minxin Pei, ‘Contradictory trends and confusing signals’ in Journal of Democracy, Volume 13, No 1, January 2003; Fred Bergsten (2006), ‘China’s Domestic Transformation: democratization or Disorder?, in Fred Bergsten, bates Gill, Nicholas R. Lardy, Derek Mitchell, China: The Balance Sheet. What the World Needs to Know Now About the Emerging Superpower. New York, pp40-72.

[v] Hall, Peter A. / David Soskice (ed) (2001), „An Introduction to Varieties of Capitalism”, in dies. (Hg.), Varieties of Capitalism: the institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp 1-68 Schmidt, Vivian A. (2000), „ Still Three Models of Capitalism? The Dynamics of Economic Adjustment in Britain, Germany, and France”, in: Susanne Lütz / Roland Czada (ed.), Die politische Konstitution von Märkten. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag, pp 39-72.

[vi]. See Jacint Jordana/David Levi-Faur (ed), The Politics of Regulation. Institutions and Regulatory reforms for the Age of Governance. Cheltenham, UK.

[vii] See T Töller, Elisabeth (2002), Komitologie. Theoretische Bedeutung und praktische Funktionsweise von Durchführungsausschüssen der Europäischen Union am Beispiel der Umweltpolitik. Opladen: Martin Lodge (2004), ‘Accountability and transparency in regulation: critiques, doctrines and instruments’, in Jordane/Levi-Faur (ed), Politics of Regulation, pp124-144.

[viii] Sandschneider 1995, Stabilität und Transformation. Opladen; Wolfgang Merkel (2000), Transformationstheorie. Opladen

[ix] Fukuyama (1992), The End of History and the Last Man. Penguin.

[x] David Shambaugh (2008), Between Atrophy and Attrition: The Communist Party of China. New York: CUB.

[xi] See Ding Ding (2000), Politische Opposition in China seit 1989, FfM.

[xii] Will China democratize? Special edition of the Journal of Democracy, 3/2003.

[xiii] Sebastian Heilmann 2005, ‘regulatory innovation by Leninist Means: Communist Party Supervision in China’s Financial Industry’, in The China Quarterly, 181/2005, pp1-21; ders. (2005a), Policy-making and Political Supervision in Shanghai’s Financial Industry’, in Journal of Contemporary China, 14(45), 2005, pp643-668.

[xiv] Artur Benz (2001), Der moderne Staat. Grundlagen der politologischen Analyse. Oldenbourg.

[xv] David Held (2001), Global transformation. Underhill, Geoffrey R.D./Xiaoke Zhang (2003a), „Introduction: global market integration, financial crises and policy imperatives”, in dies. (Hg.), International Financial Governance under Stress. Cambridge/New York:. Pp 1-17. Weiss, Linda (2000), The Myth of the Powerless State. Ithaca/New York. Weiss, Linda (2002), „Introduction: bringing domestic institutions back in“, in: Linda Weiss (ed), States in the Global Economy. Bringing Domestic Institutions Back in. Cambridge / New York, pp 1-33.

[xvi] See Robert H. Wade (2005), ‘Bringing the state back in: Lessons from the East Asia’s Development Experience’, in IPG 2/2005, pp98-115.

[xvii] See Lütz, Susanne (2003a), Governance in der politischen Ökonomie. MPIfG Discussion Paper 03/5, Mai 2003. Köln: MPIfG Governance; Laurence, Henry (2001), Money Rules. The New Politics of Finance in Britain and Japan. Ithaca und London: Cornell University Press.

[xviii] See Jordana/Levi-Faur (2004), Politcs of Regulation; Moran, Michael (1986), „Theories of Regulation and Changes in Regulation: the Case of Financial Markets.”, in Political Studies 1986, pp 185-201 Knill, Christopher /Andrea Lenschow (2003), Modes of regulation in the Governance of the European Union: Towards a Comprehensive Evaluation. European Integration online Paper (EioP), Vol 7 (2003), No. 1; at

http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/2003-001a.htm; download 27.06.2004.

[xix] Stigler, George J. (1971), „The Theory of Economic Regulation”, in: ders. The Citizen and the State. Essays on Regulation. (Reprint from the Bell Journal of Econommics and Management Science, Spring 1971).Chicago / London: The University of Chicago Press, S. 114-141. Stigler, George J. (1971a), „The Economists’ Traditional Theory of the Economic Functions of the State”, in: ders., The Citizen and the State. Essays on Regulation. Chicago / London: The University of Chicago Press, S. 103-113 Peltzman, Sam (1976), „Toward a more general theory of regulation“, in: Journal of Law and Economics, August 1976, S. 211-240. Peltzman, Sam (1989), ”The Economic Theory of Regulation after a Decade of Deregulation”, in: Brookings Papers: Microeconomics. 1989, S. 1-59 Baldwin, Robert / Martin Cave (1999), Understanding Regulation. Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress.

[xx] See Fritz W. Scharpf (2000a), Interaktionsformen. Akteurzentrierter Institutionalismus in der Politikforschung. Opladen: Leske+Budrich Mayntz, Renate / Fritz W. Scharpf (1995), „Der Ansatz des akteurzentrierten Institutionalismus”, in: dies. (Hg.), Gesellschaftliche Selbstregulierung und politische Steuerung. Frankfurt am Main / New York: Campus-Verlag, S. 39-72.

[xxi] North 1991, Institutions and Institutional Change. New York: CUP.

[xxii] Important contributions include Margaret M. Pearson (2005), ‘The Business of Regulating Business in China. Institutions and Norms of the Emerging Regulatory State’, in World Politics, 57 (January 2005), pp 296-322; Heilmann (2005: 2005a).

[xxiii] David Levi-Faur (2005), ‘Varieties of Regulatory Capitalism: Sectors and Nations in the Making of a New Global Order’, in. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions, Vol. 19, No. 3, July 2006, pp. 363–366; John Braithwaite (2005), Neoliberalism or Regulatory Capitalism. Regulatory Institutions Network Occasional Working Paper No 5, October 2005.

[xxiv] Christopher McNally (2006), Insinuations on China’s Emergent Capitalism. East-West Center Working Paper, Politics, Governance, and Security Series No. 15, February 2006.

[xxv] Although the underlying assumption of China thereby following a similar process of development as the UK, Prussia, the Netherlands or France in the 19th and early 20th century is highly debatable for empirical reasons (international context) as well as normative one (risking to enter again a one-way perspective towards the evolution of a Western market economy).

[xxvi] Jordana/Levi-Faur (2004).

[xxvii] Ayes I, Braithwaite J (1992) Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York.

[xxviii] Bhattasali, Deepak, Shantong Li, and William Martin (2004) (Eds), China and the WTO: accession, policy reform, and poverty reduction strategies, Oxford: Oxford University Press; Jessop, Bob /Ngai-Ling Sum (2006), Beyond the regulation approach: putting capitalist economies in their place, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; Jordana, Jacint and David Levi-Faur (2003) (Eds), The politics of regulation: institutions and regulatory reforms for the age of governance, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; Massey, Patrick/Daragh Daly(2003), Competition & regulation in Ireland: the law and economics, Cork: Oak Tree Press; Sell, Susan K (2003), Private power, public law: the globalization of intellectual property rights, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[xxix] See Michael Porter, (1985) Competitive Advantage, New York: Free Press.

[xxx] See Christine Parker, Colin Scott, Nicola Lacey, John Braithwaite (2004), Regulating Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[xxxi] See Stephanie Balme and Michael Dowdle, eds., Constitutionalism and Judicial Power in China, (Palgrave, 2008).

[xxxii] See Philip Augar 1998, The Death of Gentlemanly Capitalism, London:Penguin.

[xxxiii] Jens Dammann, “A New Approach to Corporate Choice of Law”. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, Vol. 38, 2005.

[xxxiv] See Nicolas Jabko (2003), “The political foundations of the European regulatory state” in Jacint Jordana and David Levi-Faur, The Politics of Regulation Institutions and Regulatory Reforms for the Age of Governance, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

[xxxv] Deli Yang and Peter Clarke, “Globalisation and intellectual property in China”, Technovation, Volume 25, Issue 5, May 2005, Pages 545-555.

[xxxvi] Bill K. P. Chou, “Does “Good Governance” Matter? Civil Service Reform in China”, Journal International Journal of Public Administration, Volume 31, Issue 1 January 2008, p. 54.

[xxxvii] The Economist 15th December 2007.

[xxxviii] See Chinese White Paper on IPR Protection at www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-04/21/content_436276.htm

[xxxix] G. John Ikenberry, “The Rise of China and the Future of the West: Can the Liberal System Survive?”, Foreign Affairs , January/February 2008.

[xl] See V. Tanzi, (1995) “Corruption, Arm’s-Length Relationship and Market” in Fiorentian Gianluca /Sam Peltzman (1995) (Eds), “The Economics of Organized Crime”, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 161-180.

[xli] See N. Collins and M. O’Shea (2000), Understanding Corruption in Irish Politics, Cork: University Press.