I am Owusu Agyeman and I come from from Akropong in the Nkoranza district. I live here in Nkoranza town where I have my well known Ash-foam business. I sell pillows and mattresses. As you may know, my father is a chief.

I am Owusu Agyeman and I come from from Akropong in the Nkoranza district. I live here in Nkoranza town where I have my well known Ash-foam business. I sell pillows and mattresses. As you may know, my father is a chief.

I decided to go to Libya because there is no work in Ghana. Let me correct myself and say it this way: there is work in Ghana but it doesn’t fetch any money. Take farming for example. I may use two million Cedis to prepare and sow the land and when I harvest my corn I may get 1,5 million in return. What does it mean? It means I lost. I have lost money because the market prices are bad. That is why I went abroad, to get enough money to start a business in Ghana.

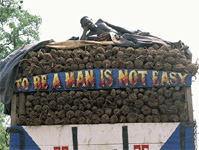

At the time when I left Ghana I was no longer a young boy, I was thirty eight years old and had a wife and three children. My wife agreed that I should go in order to provide for the family. So then we had to prepare for such a journey which is both costly and dangerous. Danger is everywhere along the way but the walking, which we call footing, through the desert, that is the greatest risk! I will tell you the story of my journey. I started here in Nkoranza in Ghana and traveled in an ordinary lorry to the border at Bawku.

I then took a car across the border to Burkino Faso and then on to Mali. Finally I went deep into Niger where you reach the desert and then another chapter starts! Those days when I traveled there, there was no such thing as group transport with Ghanaians all the way to Libya. Not at that time. Now that has changed.

Africans need no visa on the West-African continent so I had all I needed which was my passport, my vaccination card and enough money. The last one is the hardest! At border crossings I of course never tell my real plans of going to Libya for they would send me right back. So at the Ghana border I say I go to Burkina Faso to work and from Burkina Faso I say I go to work at Mali. I have a profession. I am a mechanic. So that’s what I say: I am going to work there as a mechanic. Once in Mali they ask me where I am going and I say to Niamey in Niger. I went to Niamey and then to the second biggest city which is called Agadez. I did all this with ordinary local passenger cars. It is at Agadez that the story changes!

Here you have reached the desert. Here we sit and rest along the roadside and we wait. We wait for other people who are on their way to Libya. Once there are enough people to fill a car then you go across the desert. The cars are land-cruisers, pick-ups.

Niger is a poorer country than Ghana, no jobs. There are men there in Agadez who make a living out of assembling people and organizing a car for them. There are other men who make it their job to cross the desert with us and bring us to Libya. Two of these men sit in the cabin in front and all of us travelers are packed in the back of the pickup. In my case they took us, 90 to 100 persons, into two cars. At that time, 1997, they let us pay 20,000 CFA, which is about 50 dollar per person. We were packed like maize bags, sometimes they even got more than 50 people in one land-cruiser.

Once your pick-up is filled you drive straight into the sand, there is no road. The driver finds his way by spotting old tires which are placed here and there along the trek. A tire indicates ‘straight on’ when it is parallel to the direction of the car, it means bend left or right when it is put on an angle.

On and on you drive and finally you reach the ‘Hogar-mountain’. Cars cannot cross the ‘Hogar’ because of the rocks and ravines. That is the end of your ride. Then you have to walk and climb all the way over those mountains and again walk for one or two weeks before you reach Libya. The land-cruisers have left you already, they return for a new load of passengers.

The most dangerous point in the journey is the crossing of Mount Hogar itself. First of all therefore you have to gather strength and so you sleep at the foot of the mountain. Very early before dawn the next day you take your portion of gari with shito which is your daily food. You drink some water. Then you start climbing towards the top of the Hogar. Climbing the rocks is dangerous. In my time four guys died instantly, they were Nigerians. Nigerians don’t know how to persist. Passing over the rocky trail you walk alone and follow the one before you. You step exactly the way the one before you puts his feet and if you are lucky you reach the top. Many also fall in rifts and die. At the top of the mountain there is a man who reaches out and takes your hand and pulls you up.

Then when the last man has arrived you all sit on the mountaintop. No one speaks because of tiredness. You eat. You are silent. Everybody strictly looks after his own food. You can’t have much because you cant carry it. It would not even fit in the car with all these fifty people sitting on top of each other. I may say it is like slave-trade, such cars. With water you have the same problem. Each man has one gourd of water, which means you drink only one cup a day. If you drink more you die, for the journey is three weeks and you have one gallon of water. It is simple mathematics. After having made it over the mountain you just sit there. Now you have eaten and you rest. You look and you see all that sand of the desert before you, nothing else but sand. This is like an endless beach without the sea and you have to cross that sand by foot.

Some want to go back but the car has already turned back to Agadez. They load us off the way they do with bags of maize or rice. So you go with your gari, your shito and your little water. I tell you it is a fasting journey. If you are not lucky you perish on the mountain for there are big ridges and if you slip into one of them than that is the end of you. Now follows the second trial, which is to cross that sand. If you run out of water you die.

Of our group about twenty percent were Nigerians. They are not as strong as we for they don’t farm and have not known adversity. Often you find them complaining and they are the ones that perish. There were also five women with us, all wanting to work in Libya. Furthermore some people form Mali, Chad and Niger. However most of the people crossing the desert are Ghanaians. All the women were Ghanaians, they go for prostitution jobs.

Yes the desert journey is hard. During our journey, beside those who died on the Hogar, four other Nigerians died in the desert from thirst. They had mismanaged their water. We, the Nkoranza boys, are strong and so we all keep silent and we walk. You walk till maybe nine in the evening and then you sleep for two or three hours and then you just have to get up and walk again.

We have guides, they are from Niger. They are supposed to know the desert. You know why many of us also die? Because some of the guides are not really guides and they mislead us so that we keep on roaming aimlessly in the desert. On the way going I saw a nice boy here, a nice lady there, a nice man here. All dead, fresh dead. They missed the way and perished from thirst.

But one night you walk and you suddenly see lights. They are from the most southern town in Libya, called Gut. How relieved you are then! In that City with the lights there is a car waiting for you. You just walk towards that town and you are sure to avoid any border post and suddenly you are inside Libya. Sometimes people weep because they have made it. They are there! In Gut you take a car to Saba. The roads are now tarred and you can rest. After Saba you either go to Tripoli or to Benghazi.

I went to Benghazi. This is the better city for all their police are out to arrest you in Tripoli but not in other towns. Libya is rich. Everywhere there are airports but of course we lack money so we travel by road. A car ride is cheap for petrol costs next to nothing. Not only petrol but everything is cheap in Libya. If you do well you can get free food from the Libyans because they like people from Ghana and they trust us. They don’t give food or jobs to Nigerians.

This is what happens. They call you: ‘Al’ Hadji, come! Do you want food, yes?” They give you. They give you blankets, food, everything. They have much more money than Bulgarians in Europe, a country where I also went.

From my group eight people died and I met nine fresh dead bodies of people who lost their way in the desert from other groups.

So once in Saba I went straight to Benghazi and I had it all right. I did not suffer much. They speak some English in that town because it used to be the capital of Libya, before Tripoli became the capital.

Every morning I saw plenty of our Ghana-boys, all grouped together, with wheelbarrows, ready to be hired for work. You know so many different people run that country and work there. There are Lebanese, Syrians, Iranians and Kuwaitis, Pakistani and Bangladeshi and Israelis too. The Jews pretend to be Lebanese for Al-Qathafi does not tolerate people of Israel and kills them all. The Israelis are spies for America says Al-Qathafi, that’s why he kills them. Al-Qathafi also does not tolerate Christians in Libya but he won’t kill them. You can’t worship in Libya, unless underground.

So when you arrive and, like me, you are lucky to have a profession, you can work with a company. Otherwise you wait to be hired to work by day or by hour. I told you about all my Ghanaian brothers being ready in the morning with their wheel barrels. They all assemble under some steel bridges and roofs and stand there, waiting to be called. My people are always called first because in Libya they know that we from Ghana are hard working. We can be called to wash a car, cut the lawn, do their underwear. Anything. You can be asked to clean a house for two hours and get 20 Dinars. You go back and wait again till you are called: ‘Wash the curtains’, another 30 Dinars. In a day you can earn 50 Dinar or more if you are lucky. They may give you a meal as well.

The next day you wait again after you had a nice bath and your breakfast. You stand so that the Libyans come for you. They ask: ‘Are you from Ghana?’ If you say yes they take you. If you say no, Nigeria, they ignore you. The Libyans don’t work at all, that’s why there is much work for us. That is the life for us, except for those like me who work in the big companies.

I was employed at an international company, which was run by foreigners such as Koreans, Lebanese and Egyptians. Actually, there is so much money in Libya that no Libyan works at all. They take us blacks as their laborers. I was lucky for they took me as a foreman and I got a car and a bungalow. Each month I earned 300 dollars. Mostly I was in my car, driving from one place to the next. I practically lived in the car! My company used to send me to Algeria, to Morocco and to Egypt, to Sudan and Somalia and to Bulgaria. As a works-foreman I had to go anywhere where there was a mechanic job to be done. I tried to cross to Europe. I traveled to Bulgaria by air but they repatriated me to Libya again. At that time there was a free trade zone between Libya and Bulgaria and that is how many Ghanaians then went into Europe.

From our group seventy percent were ‘by day’ workers and the others got employment at a company. More than half of all the strangers are Ghanaians. If Libyans are nice at all they are only nice to us. Nigerians are hated, they are known for their cocaine.

The ladies, do you know their job?

I can take two ladies to Libya and have them sleep in a room. I wash and dress up well and eat and then I go out and stand on the street. Some Egyptian or a Lebanese will ask ‘How much?’ I have her picture. They look. They say: ‘That one. How much?’ The Syrians are the best clients.

You negotiate like on the market. I say: ‘My brother, come here, look at the women, the pictures, how much?’ He may give an amount. You may spend some time bargaining. When you sleep twice with the same woman you have to pay more, you pay 20 Dinars. The customer comes to her house and then the woman herself also bargains. She says: ‘No. 50 Dinar’. ‘No no 20 Dinar’, says the man. So maybe the amount will be 30 Dinar. He sleeps with her for two hours and has to go. The owner of the lady collects the money. At the end of the day they will make accounts. The lady lives in the house with the man. Often these ladies are also married with these men.

Most women go to Libya in search for a job although they are warned about it and know that they will end up in prostitution. They know and they don’t know. They want to go to Libya in order to go on to Italy. But before you can do that you need money and you don’t have that money. The girls have one way to make money which is prostitution. After that they sometimes escape and go to Europe. Sometimes women are tricked into prostitution by the men. The mature ones know that. A lady is alone and you take her as your wife so she is protected. You say to each other that after all the job is only during the day and in the night you sleep with your partner together like man and wife. There is no jealousy, it is all about money. If you take three ladies to Libya you will sell two to others and you stay with one. You don’t stay with two. Prostitution is all over the world anyway. The same in Kenya, in America, in Amsterdam and in Accra. It is not so strange. Prostitution in Ghana by the way has no money in it. A rich man doesn’t pick up a girl from the street. Why would he, he can get as many girlfriends as he wants. The poor guy can’t afford anything so at most the girl gets a present for the sex.

All this goes on. The work is hard and the reason for it all is to bring money home. When I was there I would not think of loneliness or of my wife and children. No, you have work to do which is to make money. If a man gets lonely he can get a lady or if you are a lady you can get a man, if not a Ghanaian than maybe a Nigerian or someone from Chad.

More than our family we may miss our drinking together! These Islamic countries don’t allow drink and you get kicked out or imprisoned if they catch you. However we have ways… we make our own gin! The Ghanaians do that. We know how to do that, distilling in large steel barrels. We distill from millet with sugar and then we all sit somewhere hidden and we drink and get happy. The Libyans don’t, they can’t drink. Oh maybe secretly they do but they don’t know how to make the drink. We keep it our secret.

I stayed three years in Libya and then returned to Ghana. My coming back to Ghana was caused by a friend who had suffered an accident. He broke both legs. I had to see that he came back to Ghana for I felt responsible for him. I took my friend in a car all the way to Egypt because at that time there were sanctions on Libya and you could not fly from Tripoli to Ghana. I had a hard time with the man because both legs were broken and he suffered but eventually we reached the airport in Egypt. Then straight on a flight to Accra. I would not have come home if my brother had not had that accident, so I guess the ‘good Samaritans work’ brought me back to Ghana.

I was lucky to meet a German at Ghana Airport who saw me struggling with my friend and his broken legs! He helped us into a taxi and found admission in 39, the best hospital in Accra. My brother recovered well. Eventually we returned to Nkoranza together. And guess what! That that same man went away again to Libya! This time he made it on the boat sailing across to Italy. Alas I think you heard of it he was one of the four Ghanaians who died at sea because of the boat accident. It happened some years ago. Four Nkoranza boys drowned when that boat capsized. The funeral was terrible and lasted for weeks. One was from Nana Gyema Stores, one from Fiema, one from Akropong and one from Nkoranza-town here. In the meantime the wife is married again. We are survivors! Crying does not work well for us.

I have been to Nigeria too before going to Libya. That was the time that Nigeria got petrol, in 1970. Suddenly they sent us all back, by boat and by car and by whatever way. Many died on the way because of the overcrowding and the violence.

I also worked in Sierra Leone and other places and yes I will go again, I cannot sit still and I want to explore the world. I’m always feeling around where the good places are. Japan is good for us now but Europe is not good anymore, The Netherlands especially bad. We like the UK and Japan and the USA. If you have some money you always get a visa, always. If you can show 10,000 or 20,000 euro you can go to Holland for a shopping trip and everywhere else too.

Only terrorism has become a problem for us now. I will not go to Libya again. Too many workers and not enough work. Fewer people now go to Libya, unless they already have the money for the boat to Italy. Then… straight to Europe!

I like traveling, that is part of it too. I have a good business here, however. Still if I had enough money then I would take up farming also. Farming without having to depend on nature. I would start an irrigation project and grow tomatoes in the dry season. That is where the money is, have you seen it? I like adventure and I go where the money is.