July 25, 2002 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Constitution of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico. A Spanish colony until 1898, the Island became an overseas possession of the United States after the Spanish-Cuban-American War. In 1901, the U.S. Supreme Court defined Puerto Rico as an unincorporated territory that was ‘foreign to the United States in a domestic sense’ because it was neither a state of the American union nor a sovereign republic.[i] In 1917, Congress granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans, but the Island remained an unincorporated territory of the United States. In 1952, Puerto Ricobecame a Commonwealth or Free Associated State (Estado Libre Asociado, in Spanish).[ii]

July 25, 2002 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Constitution of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico. A Spanish colony until 1898, the Island became an overseas possession of the United States after the Spanish-Cuban-American War. In 1901, the U.S. Supreme Court defined Puerto Rico as an unincorporated territory that was ‘foreign to the United States in a domestic sense’ because it was neither a state of the American union nor a sovereign republic.[i] In 1917, Congress granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans, but the Island remained an unincorporated territory of the United States. In 1952, Puerto Ricobecame a Commonwealth or Free Associated State (Estado Libre Asociado, in Spanish).[ii]

The Commonwealth Constitution provides limited self-government in local matters, such as elections, taxation, economic development, education, health, housing, culture, and language. However, the U.S. government retains jurisdiction in most state affairs, including citizenship, immigration, customs, defense, currency, transportation, communications, foreign trade, and diplomacy.

In this chapter, we analyze the socioeconomic costs and benefits of ‘associated free statehood’ in Puerto Rico. To begin, we describe the basic features of the Commonwealth government, emphasizing its subordination to the federal government. Second, we examine the impact of the Island’s political status on citizenship and nationality, which tend to be practically divorced from each other for most Puerto Ricans. Third, we focus on the cultural repercussions of the resettlement of almost half of the Island’s population abroad. Fourth, we review the main economic trends in the half-century since the Commonwealth’s establishment, particularly in employment, poverty, and welfare. Fifth, we recognize the significant educational progress of Puerto Ricans since the 1950s, largely as a result of the government’s investment in human resources. Sixth, we assess the extent of democratic representation, human rights, and legal protection of Puerto Ricans under the current political status. Finally, we identify crime, drug addiction, and corruption as key challenges to any further development of associated statehood in Puerto Rico. Our thesis is that the Estado Libre Asociado has exhausted its capacity to meet the needs and aspirations of the Puerto Rican people, a task that requires a major restructuring of U.S.-Puerto Rico relations.

Over the past decades, the three major political parties – as well as the majority of the Puerto Rican electorate – have expressed a desire to reform Commonwealth status. Major differences of opinion remain regarding how exactly to complete the Island’s decolonization, whether through independence, enhanced autonomy, or full annexation to the United States.

Political Status

The origins of the Commonwealth formula can be traced to the political crisis confronting the United States and other European powers in the Caribbean in the wake of the Great Depression and the beginning of World War II. Before 1950, several military decrees (1898-1900) and two organic laws, the Foraker Act of 1900 and the Jones Act of 1917, had governed relations between Puerto Rico and the United States. Until 1952, Puerto Ricans had little participation in their own government; the governor, most members of the executive cabinet, and the justices of the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico were Americans appointed by the President of the United States. In short, the Island’s political system was that of a classic colony.

During the war, the Caribbean became the United States first line of defense against the German threat in the Americas, and Puerto Rico was the American key to the Caribbean. U.S. Army strategists ‘conceived of Puerto Rico, together with Florida and Panama, as forming a defensive air triangle that would guard the eastern approaches to the Caribbean and act as a stepping stone to South America’.[iii] U.S. military interests dictated the necessity for political stability in their own ‘backyard’.

The wartime appointed governor of Puerto Rico, Rexford G. Tugwell, a leading member of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal brain trust and member of the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission, articulated this new geopolitical vision.[iv]

In 1940, the Popular Democratic Party (PDP), founded by Luis Muñoz Marín, won the elections in Puerto Rico, and continued to control the local government until 1968. U.S. security interests in the Caribbean and the post-World War II decolonization drive enabled PDP leaders to engineer and implement a new and comprehensive strategy of economic and political reform in Puerto Rico. This strategy reconfigured the key features of American colonial tutelage over the Island, by adding concessions and federal programs to chart the postwar political and economic course. If Puerto Rico was to be the American key to the Caribbean, it had to become an example of American democracy and economic largesse to its neighbors. The basic rationale for Commonwealth status was that it provided a greater measure of self-rule, short of independence, and a more effective political framework for economic development than the earlier colonial regime.

In 1946, President Harry S. Truman named the first Puerto Rican governor, Jesús T. Piñero, and in 1948 Congress passed a law allowing the governor’s election. In 1950, Congress passed and the President signed Law 600, authorizing a convention to draft the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. The constitution was first approved by Congress (after requiring several changes, especially in its bill of rights),[v] and then by the people of Puerto Rico. In a referendum held on March 3, 1952, eighty-one percent of the Island’s electorate supported the creation of the Estado Libre Asociado.

The new political status did not substantially alter the legal, political, and economic relations between Puerto Rico and the United States. The U.S. dollar was Puerto Rico’s official currency since 1899; the Island was under U.S. customs control since 1901; Puerto Ricans were U.S. citizens since 1917; federal labor legislation and welfare benefits had been extended to the Island since the 1930s; and Puerto Ricans could elect their governor since 1948. In 1953, Harvard Professor of International Law Rupert Emerson emphasized the essentially symbolic nature of the Commonwealth: ‘[T]he most distinctive element is that they [the Puerto Rican people] now have for the first time in their history given themselves a constitution and given their consent to their relationship to the United States (…) It is arguable that the status which they now have does not differ greatly in substance from that which they had before; but to press that argument too far would be to ignore the great symbolic effect of entering into a compact with the United States and governing themselves under an instrument of their own fashioning’.[vi] Nonetheless, Commonwealth status provided more autonomy for Puerto Rico. Henceforth, the local governor would appoint all cabinet officials and other members of the executive branch; the local legislature could pass its own laws and determine the government’s budget; and the judicial system would amend its civil and criminal code, without federal interference – as long as such measures did not conflict with the U.S. Constitution, laws, and regulations.

Because the Commonwealth formula is not part of U.S. federal doctrine, the prevailing judicial interpretation is that Puerto Rico continues to be an ‘unincorporated territory’ that ‘belongs to but it is not a part of the United States’.[vii] Under Law 600, the U.S. Congress and President retain sovereignty over Puerto Rico and can unilaterally dictate policy relating to defense, international relations, foreign trade, and investment. Congress also reserves the right to revoke any insular law inconsistent with the Constitution of the United States. Moreover, federal regulations may be applied selectively, resulting in both concessions and revocations of regulatory privileges or advantages in any decision of the President or law enacted by Congress. In addition, many U.S. constitutional provisions – such as the requirement of indictment by grand jury, trial by jury in common law cases, and the right to confrontation of witnesses – have not been extended to Puerto Rico and other unincorporated territories.[viii]

Furthermore, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico does not have voting representation in the U.S. Congress. Because the Island’s residents do not pay federal taxes,[ix] they are only entitled to one nonvoting member in the House of Representatives, called a Resident Commissioner. Pro-statehood and pro-independence supporters argue that Commonwealth is a colonial status because of the lack of effective representation and unrestricted congressional and executive power over Puerto Rico. Commonwealth advocates argue that this formula represents a compact among equals, which can be renegotiated to remedy its salient flaws. As the United States-Puerto Rico Commission on the Status of Puerto Rico enthusiastically concluded in 1966, the Commonwealth relationship ‘constitutes a solemn undertaking, between the people of the United States acting through their Federal Government and the people of Puerto Rico acting directly as well as through their established governmental processes’.[x] Nevertheless, the advantages and disadvantages of the Estado Libre Asociado have been endlessly debated over the past five decades.

Citizenship and Nationality

Paradoxically, the Island’s contested political status has strengthened rather than weakened feelings of national identity among Puerto Ricans. In a poll conducted on the Island in 2001, more than 60 percent of the respondents chose Puerto Rico as their nation. About 17 percent considered both Puerto Rico and the United States as their nations, and only 20 percent mentioned the United States alone.[xi] Another survey found that an even higher proportion – more than 93 percent – identified themselves as Puerto Rican, alone or in some combination (including black, white, mulatto, Caribbean, or a member of another ethnic minority, such as Cuban and Dominican).[xii] Other empirical studies, conducted both on the Island and in the mainland, have confirmed that most Puerto Ricans see themselves as a distinct nation and share a specifically Puerto Rican, not American or Latino, identity.

Even in the mainland, Puerto Ricans seldom align themselves primarily with a pan-ethnic category such as Hispanic.[xiii] Recent debates on Puerto Rican cultural politics have focused on the demise of political nationalism on the Island, the rise of cultural nationalism, and continuing migration between the Island and the mainland. Many writers concur on the strength, clarity, and popularity of contemporary Puerto Rican identity.[xiv] Unfortunately, much of this work has centered on the Island and neglected how identities are reconstructed in the diaspora.[xv] Although few scholars have posited an explicit connection between cultural nationalism and migration, we would argue that they are intimately linked. For instance, most Puerto Ricans value their U.S. citizenship and the freedom of movement that it offers, especially unrestricted access to the continental United States. In recent years, Puerto Ricans have claimed the ability to migrate to the mainland and back to the Island as a fundamental right derived from their ‘permanent association’ with the United States. Ways to preserve this ‘right’ are currently being considered under all political status options (Commonwealth, free association, and independence, in addition to statehood). However, important sectors of the U.S. elite (including leading Congress members and businesspeople) do not see such options as realistic or even constitutionally possible.

As Puerto Ricans move back and forth between the two places, territorially grounded definitions of national identity become less relevant, while transnational identities acquire greater prominence. Transnational migration has often bred ‘long distance nationalism’, the persistent claim to a national identity by people born and raised away from their homeland, or residing outside of it for long periods of time.[xvi] For example, Puerto Ricans in Chicago have created Paseo Boricua (Puerto Rican Promenade) a mile-long strip along Division Street near Humboldt Park. This area features two giant Puerto Rican steel flags, the Puerto Rican Cultural Center, la casita de don Pedro (a small house in honor of nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos), the Roberto Clemente School, and celebrations of street festivals such as Three Kings Day, the People’s Parade, and patron saints’ commemorations.[xvii] Similarly, Puerto Rican enclaves in New York, Philadelphia, Hartford, Orlando, and elsewhere express a strong pride in their national origins. The vast majority of Puerto Ricans, on and off the Island, imagine themselves as part of a broader community that meets all the standard criteria of nationality – a shared history, a homeland territory, a vernacular language, and shared culture – except sovereignty. What has declined over the past five decades is the public support for the proposition that Puerto Rico should become an independent country, apart from the United States.

How can most Puerto Ricans imagine themselves as a nation, even though few of them support the creation of a separate nation-state?[xviii] We address this issue by making a careful distinction between political nationalism – based on the doctrine that every people should have its own sovereign government – and cultural nationalism – based on the assertion of the moral and spiritual autonomy of each people, as expressed in the protection of its historical patrimony as well as its popular and elite culture.[xix] Whereas political nationalism insists on the necessity of independence, cultural nationalism can be reconciled with other forms of self-determination, such as free association. Whereas political nationalists concentrate on the practical aspects of achieving and maintaining sovereignty, cultural nationalists are primarily concerned with celebrating or reviving a cultural heritage, including the vernacular language, religion, and folklore. Cultural nationalism conceives of a nation as a creative force; political nationalism equates the nation with the state. The distinction between these two forms of nationalism is made only for analytical purposes, for in practice they often overlap.

While political nationalism is a minority position in contemporary Puerto Rico, cultural nationalism is the dominant ideology of the Commonwealth government, the intellectual elite, and numerous cultural institutions on the Island as well as in the diaspora. However, the U.S. government and most international organizations have not officially recognized the existence of a Puerto Rican nationality. Still, most Puerto Ricans believe that they belong to a distinct nation – as validated in their participation in such international displays of nationhood as Olympic and professional sports and beauty pageants. In 2001, the nearly simultaneous victories of Félix ‘Tito’ Trinidad as world boxing champion and Denise Quiñones as Miss Universe sparked a wave of nationalistic pride among Puerto Ricans of all political parties.[xx] At the same time, most Puerto Ricans have repeatedly expressed their wish to retain their U.S. citizenship, thus pulling apart the coupling that the very term ‘nation-state’ implies. Put another way, the vast majority of Puerto Ricans do not want to separate themselves politically from the United States, but they consistently affirm their cultural identity as different from that of Americans.

The extension of U.S. citizenship to the Island in 1917 undermined the juridical bases of a separate identity among Puerto Ricans.[xxi] In 1996, the pro-independence leader Juan Mari Bras resigned his U.S. citizenship to test the feasibility of traveling abroad and voting with a Puerto Rican passport. However, in 1998, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that, under current federal laws, Puerto Ricans could not legally claim a nationality apart from the United States. But Puerto Ricans maintain a sharp distinction between the legal and cultural dimensions of identity, insisting on separating their U.S. citizenship from their Puerto Rican nationality. While all Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens by birth, few consider themselves Puerto Rican-Americans or Americans.

Emigration and Immigration

In addition to its unresolved political status, Puerto Rico is increasingly a nation on the move: a country whose porous borders are incessantly crisscrossed by migrants coming to and going away from the Island. Since the 1940s, more than 1.6 million islanders have relocated abroad. According to the 2000 Census, 47.2 percent of all persons of Puerto Rican origin lived in the United States. At the same time, the Island has received hundreds of thousands of immigrants since the 1960s, primarily return migrants and their descendants, and secondarily citizens of other countries, especially the Dominican Republic and Cuba. By the year 2000, 9.3 percent of the Island.s residents had been born abroad, including those born in the mainland of Puerto Rican parentage.[xxii] This combination of a prolonged exodus, together with a large influx of returnees and foreigners, makes Puerto Rico a test case of transnationalism, broadly defined as the maintenance of social, economic, and political ties across national borders. The growing diversity in the migrants’ origins and destinations undermines traditional discourses of the nation based on the equation among territory, birthplace, citizenship, language, culture, and identity. It is increasingly difficult to maintain that only those who were born and live on the Island, and speak Spanish, can legitimately be called Puerto Ricans. As the sociologist César Ayala puts it, the Puerto Rican case suggests that ‘the idea of the nation has to be understood not as a territorially organized nation state, but as a translocal phenomenon of a new kind’.[xxiii]

We argue that diasporic communities are part of the Puerto Rican nation because they continue to be linked to the Island by an intense and frequent circulation of people, identities, and practices, as well as capital, technology, and commodities. Over the past decade, scholars have documented the two-way cultural flows between many sending and receiving societies through large-scale migration. Sociologist Peggy Levitt calls such movements of ideas, customs, and social capital ‘social remittances’, which produce a dense transnational field between the Dominican Republic and the United States.[xxiv] Similarly, Puerto Ricans moving back and forth between the Island and the mainland carry not only their luggage, but their cultural baggage: practices, experiences, and values. Culturally speaking, the Puerto Rican nation can no longer be restricted to the Island, but must include its diaspora.

Five decades of uninterrupted migration have unsettled the territorial and linguistic boundaries of national identity in Puerto Rico. For instance, second-generation migrants – often dubbed pejoratively ‘Nuyoricans’ on the Island – may speak little Spanish but still define themselves as Puerto Rican. While the Spanish language continues to be a basic symbol of national identity on the Island, it has become a less reliable mark of Puerto Ricanness in the mainland. Anthropologist Ana Celia Zentella has documented that many migrants believe that speaking English is compatible with being Puerto Rican.[xxv] In contrast, for most native-born residents of the Island, Spanish is their ‘mother tongue’. According to the 2000 census, 14.4 percent of the Island’s population speaks only English at home, while 85.4 percent speak Spanish only.[xxvi] It remains unclear whether return migration will expand the traditional discourse of Puerto Rican cultural nationalism to include English monolinguals and bilinguals, as well as those living outside the Island.

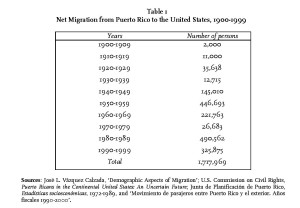

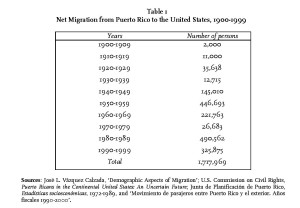

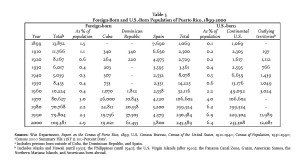

Table 1 – Net Migration from Puerto Rico to the United States, 1900-1999

Table 1 presents a rough estimate of the net migration between Puerto Rico and the United States throughout the twentieth century.[xxvii] These figures show that Puerto Rican emigration first acquired massive proportions during the 1940s, expanded during the 1950s, tapered off during the 1970s, and regained strength during the 1980s. According to these figures, almost 8 percent of the Island’s inhabitants moved to the United States during the 1990s. Although the exact numbers can be disputed, the most recent Puerto Rican diaspora may have surpassed the one that took place in the two decades after World War II.

Table 2 shows the growth of the Puerto Rican population in the United States between 1900 and 2000. The exodus was relatively small until 1940, when it began to expand quickly. After 1960, the mainland Puerto Rican population grew more slowly, but faster than on the Island. Today, the number of stateside Puerto Ricans closely approximates those on the Island. Because of continued emigration, Puerto Ricans abroad will probably outnumber islanders in the next decade.

As the exodus to the mainland has accelerated, immigration to the Island has continued apace. Between 1991 and 1998, Puerto Rico received 144,528 return migrants. In 1994-1995 alone, 53,164 persons left the Island, while 18,177 arrived to reside there. Nearly 95 percent of those who moved to the Island were return migrants and their children. Furthermore, thousands of Puerto Ricans have engaged in multiple moves between the Island and the mainland. In a 1998 survey, almost 20 percent of the respondents had lived abroad and returned to the Island, while another 3 percent had moved back and forth at least twice.[xxviii]

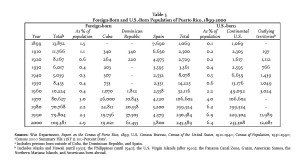

Table 3

At the same time, the Island’s population has become increasingly diverse regarding nativity. Table 3 summarizes the demographic trends in the foreignborn and U.S.-born population of Puerto Rico during the twentieth century. On the one hand, the Island’s foreign residents diminished greatly between 1899 and 1940, largely as a result of the decline in Spanish immigration. After 1940, especially between 1960 and 1970, the foreign-born population increased rapidly, primarily as a consequence of immigration from Cuba and the Dominican Republic. Smaller numbers of people have come from Spain, Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela, Argentina, China, and other countries. The U.S. mainland-born population in Puerto Rico has increased spectacularly since the beginning of the twentieth century. Most of this growth has been due to the return of Puerto Ricans and their offspring born abroad. By the end of the century, mainland-born residents of Puerto Rican descent were one of the fastest-growing sectors of the Island’s population. A smaller number of Americans has also moved to the Island. In 1990, the census counted 16,708 persons born in the United States, whose parents were also born there, living in Puerto Rico. The 2000 Census found that 6.1 percent of

Puerto Rico’s population had been born in the United States and that 3.2 percent had been living there in 1995.[xxix] In short, the Island is simultaneously undergoing three major types of population movements: emigration, return migration, and foreign immigration. Puerto Rico has become a veritable crossroads for people of various national origins and destinations.[xxx]

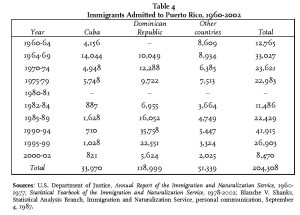

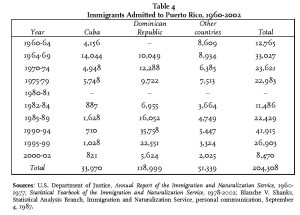

Table 4 – Immigrants Admitted to Puerto Rico, 1960-2002

After 1960, Puerto Rico became an attractive destination for Caribbean immigrants, especially Cubans and Dominicans (see table 4). Two major political events in neighboring countries signal the beginning of this period: the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and the assassination of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo, the dictator of the Dominican Republic, in 1961. Furthermore, U.S. marines invaded Santo Domingo in April 1965, after a local coup d’état and civil war. The political turmoil and material hardship in these neighboring countries, combined with the Island’s rapid economic growth during the 1960s, brought nearly 34,000 Cubans and 119,000 Dominicans to Puerto Rico over the past four decades. More than 51,000 immigrants came from other countries, primarily in Latin America.[xxxi] The growing demand for cheap labor in certain economic niches, such as domestic service, construction, and coffee agriculture, continues to draw Dominicans and other foreigners to the Island. Thus, the Puerto Rican situation presents the apparent contradiction of a growing immigrant population – one of the largest in the Caribbean – along with sustained emigration to the United States.

In the long run, exporting and importing labor has not been a viable development strategy for Puerto Rico. Despite decades of enduring emigration, unemployment rates have never fallen below 10 percent. Living standards have deteriorated over the past two decades. Almost half of the population still lives under the poverty level. An increasing proportion depends on transfer payments from the U.S. government, particularly for nutritional and housing assistance. The Island’s economic outlook seems bleak, especially after the elimination of Section 936 of the Internal Revenue Code in 1996, which provided tax exemptions to U.S. companies operating on the Island. Salaries have not kept apace with the rising cost of living – especially in housing, transportation, education,[xxxi] food, and basic services such as electricity and running water. Consequently, migration to the mainland will most likely increase.

Economic Development

Chart 1 summarizes the pillars of the Commonwealth’s economic policies:

(1) common defense,

(2) common currency,

(3) common citizenship,

(4) selective application of federal labor laws and regulations,

(5) federal tax exemptions and special quotas, and

(6) local tax exemptions.

These juridical and political principles have been configured and reconfigured through time by federal and insular laws, provisions, and regulations to produce policy outcomes beneficial to the Commonwealth government and U.S. corporations on the Island. Because Congress has the power to alter, and has altered, the regulatory substance of these principles, they have become ‘permanent but wobbly’ pillars of the Commonwealth’s development strategy.[xxxii]

________________________________________________

Chart 1 Pillars of the Economy of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico

Common Defense

1898–U.S. military bases are established in Puerto Rico.

Common Currency

1899–The U.S. dollar becomes the official currency of Puerto Rico by presidential decree.

Common Market

1901–Puerto Rico is included in the U.S. Customs territory and coastwise shipping laws. Federal laws and rules apply to international and interstate business and commerce. The Federal District Court is established in Puerto Rico to deal with interstate disputes.

Common Citizenship

1917–The Jones Act extends U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans during World War I.

Federal Welfare Programs and Transfer Payments

1934–New Deal Programs are extended to Puerto Rico through the Puerto Rico Emergency Relief Administration (PRERA) and the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration (PRAA).

1975–Federal public welfare programs, e.g., food stamps and nutritional assistance

programs, are extended to Puerto Rico.

Selective Application of Federal Labor Laws and Regulations

1934–The Fair Labor Standards Act is extended to Puerto Rico.

1947–The Taft-Harley Act is extended to Puerto Rico.

Federal Tax Exemptions and Special Quotas

1954–Section 931 of the Internal Revenue Code is applied to Puerto Rico.

1965–Presidential Proclamation 3279 establishes special oil import quotas.

1976–Section 936 of the Internal Revenue Code is approved.

1982–The Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) is approved.

1993–The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) is approved.

Local Tax Exemption

1948–The Industrial and Tax Incentive Act is approved in Puerto Rico, with modifications in 1963, 1978, 1987, and 1998.

_________________________________________________

Operation Bootstrap was the economic corollary of the Commonwealth political status. The PDP government’s policies opened a new chapter in the history of development economics by attempting to demonstrate the viability of industrialization in a small island with few natural resources. Teodoro Moscoso, the architect of what would later be known as ‘industrialization by invitation’ or the maquiladora model, put together a technocratic structure combining the features of a think tank with the connections of public relations firms. Among the young economists hired by Moscoso were the future Nobel laureates Arthur Lewis, John Kenneth Galbraith, and Wassily Leontief. The prominent planner Harvey S. Perloff was one of the masterminds of Operation Bootstrap. Consultants such as Arthur D. Little, Robert H. Nathan and Associates, and public relations firms such as McCann Erickson and Young and Rubicam were also part of the Bootstrap brain trust.[xxxiii]

Economists, planners, and consultants collaborated to promote industrial development in a small-scale economy. Public relations firms targeting U.S. investors then repackaged their message. Widely disseminated through publications such as Fortune, Baron’s, Times Magazine, The Wall Street Journal, and the New York Times, the message highlighted the Island’s unique advantages as a U.S. possession: free access to the mainland market, a dollar economy, low wages, and, above all, total tax exemption from local and federal taxes. Former Governor Roberto Sánchez Vilella once quipped that Americans believed that no one could escape death and taxes, but Puerto Ricans were offering them an escape to the latter.[xxxiv]

Operation Bootstrap radically transformed the Island’s economy and society between 1950 and 1970. Gross national product (GNP) annual rates of real growth averaged 5.3 percent in the 1950s and 7 percent in the 1960s. Real wages, measured in 1984 prices, grew steadily from a weekly average of US$41.64 in 1952 to US$153.18 in 1972. The gender gap in wages declined by 19 percent during the same period. Although income distribution did not improve substantially in the short term, by the 1970s the Puerto Rican middle class was thriving and engaged in conspicuous consumption. Expenditures in durable consumer goods rose from 8.2 percent of personal expenditures in 1950 to 16.1 percent in 1970 (remaining at that level for the rest of the century), accompanied by increases in the consumption of services. Unemployment declined from 12.9 percent in 1950 to 10.7 percent in 1970. Manufacturing employment rose from 55,000 jobs in 1950 to 132,000 in 1970, while the number of workers in domestic service and the home needlework industry declined from 82,000 in 1950 to 15,000 in 1970.[xxxv]

Without the ‘advantages’ of Commonwealth (chart 1), the rapid growth of the 1950s and 1960s would have been impossible’ Improvements in wages and employment were directly related to one of the pillars of the Commonwealth, U.S. citizenship, and one of its key consequences, the free movement of labor between the Island and the mainland. Between 1950 and 1970, an estimated 684,000 Puerto Ricans migrated to the United States, mostly to the East Coast.[xxxvi] According to economist Stanley Friedlander, had such mass migration not taken place, the Island would have faced an unemployment rate of 22.4 percent in 1960, as opposed to the actual rate of 13.2 percent.[xxxvii] The export of surplus labor thus became part of the economic strategy, helping to reduce the country’s population growth and unemployment levels. As government planners predicted in the 1940s, migration became a survival strategy for thousands of Puerto Rican families.

The economic significance of the diaspora can be gauged from the migrants’ monetary transfers to their relatives on the Island. Although much smaller in volume than in neighboring countries like the Dominican Republic and Cuba, private remittances to Puerto Rico increased more than eleven-fold from approximately US$47 million in 1960 to nearly US$549 million in 1999.[xxxviii] Together with the larger amounts of transfer payments from the U.S. government, migrant remittances are a growing source of support for the Island’s poor. They represented about half of the net income generated by the tourist industry in 1997.[xxxix]

Between 1950 and 1970, Operation Bootstrap and the Commonwealth were the economic and political expression of an arrangement that seemed mutually advantageous to both the governments and peoples of the United States and Puerto Rico. A prosperous Puerto Rico would play the symbolic role of political showcase during the Cold War, as well as the more traditional role of U.S. naval base in the Caribbean. In particular, the U.S. government promoted the Island as a democratic and capitalist alternative to the Cuban Revolution after 1959.

Half a century after its creation, the Commonwealth’s economic deterioration contrasts with the promise of the first two decades. Between the mid-1970s and 1980s, the Puerto Rican economy skidded uncontrollably. Growth faltered, unemployment soared, and wages hit a plateau that would become the norm for the remainder of the twentieth century. While some blamed the 1973 oil crisis and the second oil shock of 1978, others realized that the Puerto Rican economy was structurally compromised. In 1974, the Nobel Prize winner in economics, James Tobin, headed the Governor’s Committee for the Study of Puerto Rico’s Finances, which concluded that the Commonwealth’s main problems were its economic openness and dependency. The local government did not have the power or policy mechanisms to chart an effective economic strategy outside the limits of its peculiar relation with the United States. The government could adjust its finances (cut spending, raise taxes), but the Commonwealth structure constrained the wider economic implications of its public policies.[xl] In the last quarter of the twentieth century, Puerto Rico changed from a model of political and economic modernization to a high-cost and politically contentious corporate tax haven.[xli]

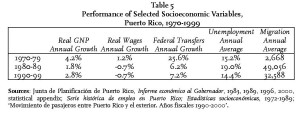

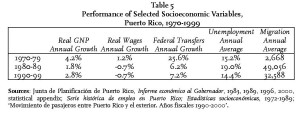

Table 5 – Performance of Selected Socioeconomic Variables, Puerto Rico, 1970-1999

Crisis and Welfare

Table 5 presents the performance of selected socioeconomic variables on the Island over the last three decades of the twentieth century. At first sight, the data suggest that the Puerto Rican economy never recovered from the downturn of the 1970s, and that the massive injection of federal funds in welfare payments and the return to mass migration merely served to alleviate poverty and unemployment. Commonwealth opponents (both pro-statehood and pro-independence supporters), as well as some of its advocates, argue that the Island’s economy has been adrift during the past three decades and that federal subsidies and concessions have only palliated the major socioeconomic problems.

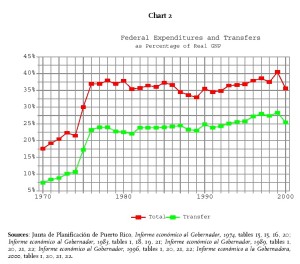

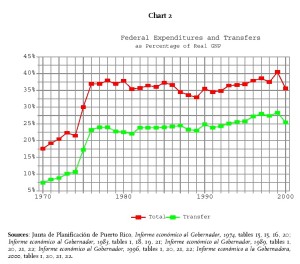

A look at the levels of federal disbursements in Puerto Rico over the last three decades of the twentieth century seems to confirm the perception discussed. Chart 2 presents total federal expenditures and federal transfer payments as a percentage of the Island’s gross national product (GNP) from 1970 to 2000 in real prices, using the Commonwealth government’s standard 1954 price index to adjust for inflation. Federal expenditures and transfers have played an increasing role in the Puerto Rican economy. During the 1970s, total federal disbursement and federal transfers grew at a fast rate (13 and 18 percent per year, respectively). Federal disbursements came to represent more than one third of the GNP while federal transfers came to represent between one fifth and one fourth of the GNP. But after a quick burst in the 1970s, federal disbursements leveled off. The largest and fastest growing share of federal expenditures were transfers to individuals.[xlii]

A close analysis of federal disbursements, however, reveals a complex picture. The introduction of the food stamps program in 1975 spearheaded the dramatic increase in federal transfer payments to Puerto Rico. The program began with an allocation of US$388.4 million in 1975 and nearly doubled to US$754.8 million in 1976. Federal aid for nutritional assistance represented about 10 percent of Puerto Rico’s GNP between 1976 and 1978, tapering off to around 5 percent by the mid-1980s and between 3 and 4 percent in the 1990s. Six programs led the rapid growth in federal transfer payments during the seventies: social security; veterans. benefits; Medicare; food stamps; the Basic Educational Opportunity Grants program (BEOG, later known as Pell Grants); and the mortgage and rent programs, such as Federal Housing Administration (FHA) loans and ‘Section 8’ subsidies.

In short, most federal transfer payments to Puerto Rico are not simply welfare, but earned benefits, especially social security and veterans’ benefits. Between 1980 and 2000, the combined share of federal transfers in nutritional assistance, housing subsidies, and scholarships declined from 35.8 percent to 23 percent, while social security and veterans benefits together increased from 47.7 percent to 56.2 percent. As U.S. citizens by birth, Puerto Ricans serve in the U.S. armed forces, pay social security contributions on the Island as well as in the mainland, and can move freely between the two places. Likewise, the U.S. armed forces have military bases on the Island and U.S. corporations are free to move capital, goods, and services between the Island and the mainland. So are federal agencies operating in Puerto Rico, from the postal service to the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI). This unrestricted movement of labor, capital, private and public services, and law enforcement agencies has tightened the linkages between private companies and government agencies on the Island and the continent, which account for a substantial share of federal payments.

Chart 2

Unemployment and Poverty

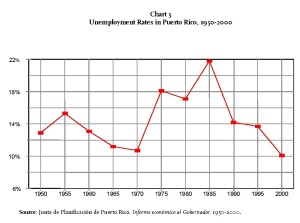

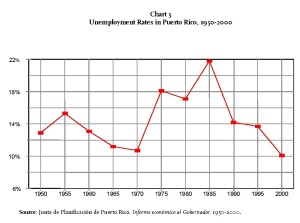

Unemployment and poverty have been structural features of the Puerto Rican economy since 1898. The promise of industrial development to reduce unemployment and end poverty did not materialize during the first half-century of Commonwealth. As shown in chart 3, unemployment never fell below 10 percent of the active labor force despite massive emigration during the fifties, sixties, eighties, and nineties (see table 1).

The main cause of poverty in Puerto Rico is unemployment. According to a recent study, families with unemployed heads of household account for 75 percent of all poor families.[xliii] Although income distribution has improved somewhat since the 1950s, the number of poor families according to the census increased steadily between 1969 and 1989, from 336,622 to 492,025. In 1999, the number of families below the poverty threshold was 450,254, the first reduction since 1969. However, the former head of the Special Communities Office of the Department of the Family, Linda Colón, has disputed this figure.[xliv]

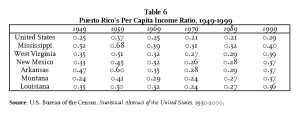

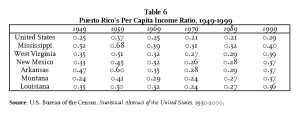

One of the goals of Commonwealth founder, Muñoz Marín, was that by the 1970s Puerto Rico would reach the per capita income level of Mississippi, the poorest state of the union according to the 1960 census. This goal appeared feasible in the sixties, when Puerto Rico’s median per capita income was 68 percent of Mississippi’s. Table 6 shows not only that the Commonwealth did not attain that goal, but that the income gap between Puerto Rico and the poorest states broadened between 1959 and 1999. Furthermore, poverty levels are worse on the Island than in the mainland. Although the poverty threshold in Puerto Rico is lower than in the United States, a larger share of the Island’s population (48 percent in 1999) than in the mainland (11 percent) is poor

Chart 3 – Unemployment Rates in Puerto Rico, 1950-2000.

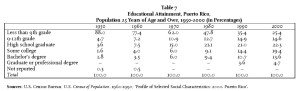

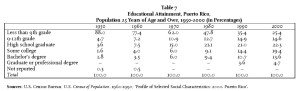

On the bright side, the educational attainment of Puerto Ricans has improved dramatically over the last five decades. For instance, the proportion of adults with a high school diploma rose from 7 percent in 1950 to 60 percent in 2000. Moreover, the share of college graduates increased from a mere 1.8 percent in 1950 to 18.3 percent in 2000 (see table 7). This extraordinary growth of the schooled population was largely due to the growing availability of federal funds for numerous educational programs – from preschool to the university – as well as the relatively large share of the Commonwealth’s budget devoted to education and culture (35.6 percent in fiscal year 2002-2003).[xlv] Puerto Ricans have benefited from greater access for U.S. minorities to higher education since the 1960s, especially in public colleges and universities on the Island and in the mainland. By the year 2000, Puerto Rico had a comparable proportion of college and graduate students (20.9 percent) to the United States (22.8 percent).[xlvi] The rapid expansion in the educational opportunities for the Puerto Rican people is one of the Commonwealth’s most important accomplishments.

Table 6 – Puerto Ricos Per Capita Income Ratio, 1949-1999

Despite such advances, the educational system of Puerto Rico faces great challenges. To begin, the quality of education has not improved significantly with the massive expansion of public instruction. On the contrary, many local schools and universities are producing poor results as measured by student retention, test scores, skills acquisition and transference, creation of knowledge, technological applications, and research and development. Second, the educational credentials of Puerto Ricans do not ensure their successful incorporation into the local labor market. In June 2003, the unemployment rate for persons with 13 years or more of schooling on the Island was 10.2 percent (compared to 12.4 percent for the entire population).[xlvii] In addition, many college graduates are forced to accept lower-status service occupations or to migrate to the  mainland in search of better jobs and salaries. Third, growing dependence on federal funds means that the Island’s educational system must submit to U.S. standards, methods, and practices. For instance, the ‘Leave No Child Behind’ Act, approved in 2002, requires that students release personal information to the U.S. armed forces for recruiting purposes. Many Puerto Rican parents have resisted what they see as an infringement of their children’s civil rights. Finally, Puerto Rico’s educational system, particularly at the university level, needs major restructuring to raise the productivity and competitiveness of human resources vis-à-vis the global economy. Teaching methods, curricular materials, and evaluation strategies are still oriented toward a professional, technocratic, and vocational philosophy that does not fit well in a postindustrial, knowledge-intensive, and high technology world.[xlviii]

mainland in search of better jobs and salaries. Third, growing dependence on federal funds means that the Island’s educational system must submit to U.S. standards, methods, and practices. For instance, the ‘Leave No Child Behind’ Act, approved in 2002, requires that students release personal information to the U.S. armed forces for recruiting purposes. Many Puerto Rican parents have resisted what they see as an infringement of their children’s civil rights. Finally, Puerto Rico’s educational system, particularly at the university level, needs major restructuring to raise the productivity and competitiveness of human resources vis-à-vis the global economy. Teaching methods, curricular materials, and evaluation strategies are still oriented toward a professional, technocratic, and vocational philosophy that does not fit well in a postindustrial, knowledge-intensive, and high technology world.[xlviii]

The Rule of Law, Democracy, and Human Rights

In some ways, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico can be considered a model of liberal democracy, ‘where politics based on free elections, multiple parties, and liberal democratic freedoms are still predominant’.[xlix] Since 1952, Puerto Rico has held thirteen Island-wide elections and eleven plebiscites and referenda without major accusations of fraud or external interference. Three political parties – the Popular Democratic Party, New Progressive Party (NPP), and Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP) – compete openly for majority support and control of the Commonwealth government. Two of them, the PDP and the NPP, have alternated in power six times since 1952. Furthermore, Puerto Ricans enjoy a high degree of civil liberties and political freedoms, compared to other Latin American and Caribbean countries. As political scientist Carl Stone has pointed out, the Island ‘has strong and free trade unions, a free press, well-developed political and civil rights, and high levels of mass political participation’.[l] The Commonwealth as well as the U.S. constitutions protect the rights to free speech, assembly, organization, freedom of religion, privacy, equal protection under the law, equal pay for equal work, and many others.

However, Puerto Ricans on the Island do not enjoy all the rights and freedoms as U.S. citizens in the mainland. This is one of the key issues shaping the status debate in Puerto Rico. According to legal scholar Efrén Rivera Ramos, ‘the extension of U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans in 1917, has probably been the most important decision made by the United States regarding the political future and the lives and struggles of Puerto Ricans’.[li] Originally an external imposition by Congress, U.S. citizenship has become one of the main pillars of continuing association between Puerto Rico and the United States. Moreover, the discourse of rights is a powerful ideological justification for the Island’ complete annexation into the American union. Today, most Puerto Ricans recognize the material and symbolic value of U.S. citizenship, including access to federally-funded programs; free movement between the Island and the mainland; and protection of some of the civil, social, and political rights guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States.[lii] Although Puerto Ricans on the Island cannot exercise the full range of these rights (such as voting for the President of the United States and voting members of the U.S. Congress), they can do so once they move to the mainland. Under Commonwealth, place of residence rather than legal status determines the extent to which Puerto Ricans enjoy their rights.

At root, the legal problem is that, in 1917, the Jones Act conferred U.S. citizenship, but not representation, upon the residents of Puerto Rico.[liii] Based on the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated territories, the U.S. Congress and Supreme Court determined that the constitution did not ‘follow the flag’. That is, not all rights, duties, laws, and regulations promulgated by the federal government applied to its overseas possessions. In effect, Puerto Ricans were granted a second-class citizenship similar to African Americans, Native Americans, and women prior to the approval of universal suffrage. As Rivera Ramos argues, ‘a distinction made early on between the political condition of the territories and the civil rights of its inhabitants has allowed for the development of a political system that may be described as a partial democracy, based on the liberal ideology of the rule of law and the discourse of individual rights, but coexisting with a situation of collective political subordination’.[liv] This contradiction between state protection of civil liberties and lack of appropriate representation in that state lies at the heart of the argument that Commonwealth is still a colonial status and, at best, an incomplete democracy.

The most flagrant violations of human rights in Puerto Rico have been committed against political dissidents. In 1987, the Puerto Rican Commission on Civil Rights found that the local police had placed more than 75,000 citizens under secret surveillance because of their political beliefs. In 1992, Puerto Rico’s Supreme Court ordered the devolution of all personal files (carpetas) documenting the ideas, activities, and organizations of the so-called subversives. The main targets for surveillance were members of the pro-independence, socialist, and student movements, but labor, feminist, cultural, religious, community, environmental, and communist groups were also included in this illegal practice. In 2000, the Commonwealth compensated more than 1,000 persons (for a total of US$3.8 million) who sued the government on the grounds of political persecution.[lv]

The recent ‘peace for Vieques’ movement was largely a struggle for human rights. On May 4, 2000, the U.S. Navy carried out Operation Access to the East, removing more than 200 peaceful demonstrators from its training grounds in Vieques, a small island municipality off the eastern coast of Puerto Rico. Since then, more than 1,640 persons were arrested for trespassing federal property, particularly during firing practices. According to the head of the Puerto Rican chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the federal government committed multiple violations of human rights, such as using pepper spray and tear gas on unarmed protestors, and denying them due process after their arrest.[lvi] Those practicing civil disobedience included a wide spectrum of political and religious leaders, university students, environmentalists, community activists, and fishermen. The protests had been sparked by the accidental death of security guard David Sanes Rodríguez during a military exercise in Vieques on April 19, 1999. Soon thereafter, Puerto Ricans of all ideological persuasions and walks of life called for an end to live bombings, the navy’s exit, and the return of military lands to the civilian residents of Vieques. In June 2000, a survey conducted by the Catholic diocese of Caguas found that 88.5 percent of the population supported the navy’s retreat from the island.[lvii] No other issue in recent history has galvanized such a strong consensus in Puerto Rican public opinion. Despite the strong solidarity displayed by Puerto Ricans on and off the Island, the U.S. Navy continued military exercises in Vieques until May 1, 2003. Without voting representation in Congress, islanders were forced to accept a presidential directive (timidly negotiated by former Governor Pedro Rosselló), that did not please most opponents of the navy’s bombing of Vieques. This directive called for the resumption of military training activities, although with inert bombs, as well as for a plebiscite to poll the views of the people of Vieques. On July 29, 2001, 68.2 percent of the voting residents of Vieques supported the navy’s immediate withdrawal from the island.[lviii] International pressure, together with a strong grassroots movement, finally forced the navy to abandon Vieques in 2003.

Other violations of human rights in Puerto Rico focus on undocumented immigrants from the Dominican Republic. U.S. immigration authorities have been accused of mistreatment and abuse of persons attempting to enter U.S. territory illegally. Saúl Pérez, president of the Dominican Committee for Human Rights, has denounced several instances of police brutality and harassment of Dominican citizens in Puerto Rico.[lix] Many Dominican workers also experience labor discrimination on account of their national origin. In 2000-2001, Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor and Human Resources received 76 complaints of this kind, most of which were presumably filed by Dominican citizens.[lx] In the wake of federal legislation restricting health, educational, and housing benefits to legal residents of the United States, the Commonwealth government may deny such basic services to undocumented Dominicans.

Drugs and Crime

Drug addiction often leads individuals to engage in criminal activity because the manufacturing and sale of illegal drugs are restricted or prohibited. Drug consumption and abuse became part of Puerto Rican popular culture in the 1960s. The Vietnam War and the hippie counterculture, as well as organized crime, contributed to the popularization of drugs among youth on the Island and in the mainland. Marihuana, heroin, and mind-altering hallucinogens, such as LSD, entered the Puerto Rican social scene, much in the same form as they did in American urban centers.

Methodologically sound estimates of the number of drug addicts in Puerto Rico are unavailable. In the year 2000, the Administration of Mental Health Services and Prevention of Addiction (known as ASSMCA, its Spanish acronym) estimated that Puerto Rico had 38,000 drug addicts, about 1.4 percent of the population, and some 130,000 alcoholics, equivalent to 4.8 percent of the population. These figures are based on a study conducted in 1997-98 by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment using a household sample. The study had clear limitations: it conducted telephone interviews of persons between 15 and 64 years old, in an island where 27 percent of the population does not have telephone service at home. To conduct interviews in households without telephones, the researchers provided the interviewees with cellular phones. Thus, the survey excluded much of the addicted teenage population and vitiated the confidentiality of telephone interviews by coming face to face with interviewees in the cellular loan transaction.[lxi] Common wisdom, even among the ASSMCA personnel contacted, is that between 4 and 5 percent of the population is addicted to or uses drugs regularly. Hence, the number of drug users ranges between 152,000 and 190,000 persons of all ages.

Similarly, it is difficult to estimate the cost of drug addiction to the Puerto Rican economy. Local and federal funds are used at all levels and from a variety of programs. Expenditures on prevention, law enforcement, and treatment are not reported separately either. For example, in 2000 the Public and Indian Housing Program awarded US$9.2 million in federal funds to the local police and US$2.8 million to ASSMCA. In 2001, ASSMCA received about US$24.5 million from seven different federal programs for services to addicts, while Puerto Rico’s Health Department received US$33.1 million in federal funds for HIV/AIDS programs from six different sources.[lxii] The growing use of federal funds suggests that the Commonwealth government has not found an adequate strategy to halt drug addiction on the Island.

A corollary of the drug problem is crime and law enforcement. As well as a major consumer of drugs, Puerto Rico is a springboard for smuggling illegal drugs into the United States. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) estimates that 20 percent of all drugs entering the Island is destined for local consumption. In the year 2000, Puerto Rico’s Police Department had intervened 1,200 ‘drug points’ (puntos de droga), the locations for the retail sale of illegal drugs (mostly crack cocaine, heroin, and marihuana). This figure suggests that the Island has at least one drug point for every three square miles. And this average excludes the sale of ‘designer drugs’, such as ecstasy, sold mostly at private parties and schools for young, middle class, ‘recreational’ drug users.

In November 1995, the DEA opened its Twentieth Field Division in San Juan. This office is responsible for Caribbean operations from Jamaica to Surinam. According to congressional testimony of the DEA administrator in 1997, Puerto Rico, with the fourth busiest seaport in North America and the fourteenth in the world, was ‘the largest staging area in the Caribbean for smuggling Colombian cocaine and heroin into the United Sates’.[lxiii] At that time, roughly 31 percent of all drugs entering the United States passed through the Caribbean corridor. The remaining 69 percent entered through Central America and Mexico.

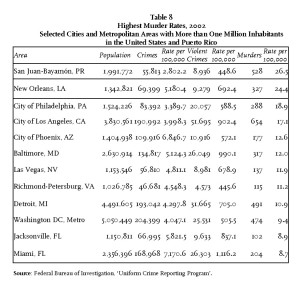

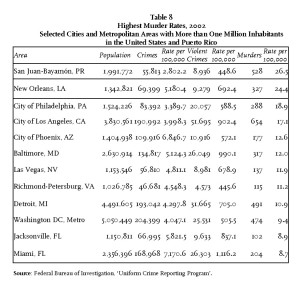

The competition in the drug trade brings extraordinarily high rates of violence. Between 1990 and 1995, Puerto Rico averaged 849 murders per year or 2.3 per day. Between 1996 and 2001, the figures dropped to 708 per year or 1.9 per day. But the real magnitude of the problem can be observed when we compare murder rates on the Island with those of other jurisdictions in the United States. According to the FBI’s ‘Uniform Crime Reports Statistics’, 2002, the state of the union with the highest murder rate is Louisiana, with 13.4 murders per 100,000 inhabitants. No other state has a rate of ten or more. Puerto

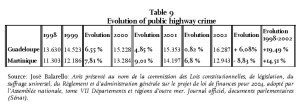

Table 8 – Highest Murder Rates, 2002 – Selected Cities and Metropolitan Areas with More than One Million Inhabitants in the United States and Puerto Rico

Rico’s murder rate is 20.1 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, only surpassed by the District of Columbia, with 46.2 murders per 100,000 inhabitants.

Table 8 compares murder and crime rates in major metropolitan areas in Puerto Rico and the United States. In 2002, the San Juan-Bayamón metropolitan area had the highest murder rate, followed by Philadelphia, of all metropolitan areas with more than one million inhabitants. The Washington D.C. metropolitan area had a much lower murder rate than the District of Columbia. Two other large metropolitan areas of Puerto Rico, with less than one million dwellers, had very high murder rates: Ponce (with 22.7) and Caguas (with 17.9).[lxiv]

Corruption

An important component of drug-related criminal activity is money laundering. In published congressional testimony, DEA officials have argued that Colombian drug cartels use Puerto Rico as a money-laundering center, but have not revealed specific figures on this practice. Since April 1996, the U.S. Department of the Treasury requires banks and financial institutions to file ‘suspicious activities reports’ (SARs) on certain transactions that are deemed suspicious or unusual. Between 1996 and 2000, local banks and financial institutions filed 505,491 SARs. Puerto Rico ranked number 33 in the United States, with California, New York, Florida, and Texas leading the list with most SARs.[lxv]

According to the DEA, a frequently used drug money-laundering tool in Puerto Rico is the casa de cambio or casa de envío de valores, a currency office that ‘wires’ cash to other countries. In Puerto Rico, most of these establishments process the sending of remittances by Dominican migrants to their families in the Dominican Republic. Whereas most remittance agencies are legitimate businesses, some operate primarily as fronts for illegal transactions.[lxvi]

Large financial institutions have also been implicated in these practices. A Spanish judge recently visited Puerto Rico to investigate allegations of money laundering by the Banco Bilbao Vizcaya, but did not file any charges. In January 2003, Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, the Island’s largest bank, paid US$21.6 million in penalties to settle accusations of money laundering by the U.S. Department of Justice.[lxvii]

Besides drug-related money laundering, much of it is related to government fraud in Puerto Rico. Since 1998, corruption among high-ranking government employees of the Rosselló administration (1993-2000) has been well documented. Many public officials have been accused and convicted of funneling federal funds from grants and special contracts for both personal gain and for financing political campaigns for the NPP. The former Secretary of Education, Víctor Fajardo, pleaded guilty to federal charges involving a scheme in which contracts were awarded to contractors in exchange for a kickback amounting to 10 percent of the contract. The secretary personally appropriated more than US$3 million, some of which he kept in a vault in his home because depositing such large sums of money in a local bank would have prompted a SAR and an investigation by the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Fraud and extortion cases involving Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) relief funds for hurricane Georges in 1998 have been brought against five mayors from the NPP and two from the PDP. These actions of mismanagement involved nearly US$22.6 million (an average of US$7.53 million per municipality) in funds approved by FEMA for municipal cleanup. The mayors were accused of extorting from or conspiring with contractors to appropriate millions of dollars from FEMA funds by billing the agency for services not rendered.[lxviii] Since 1999 the Puerto Rican press regularly reports the prosecution of cases for similar schemes of extortion, laundering, and misappropriation of funds. The agencies where the most notorious cases of corruption have been discovered are those with the highest rates of federal funding, namely, education, health, and housing. Between 1990 and 2000, the Island’s Department of Education received between 21 percent and 32 percent of all federal grant moneys awarded to Puerto Rico. The share of the local Health Department increased from 5.6 percent to 23.2 percent of all the grants. The Housing Department received more than 90 percent of its funding from federal sources. Likewise, the nearly US$800 million for hurricane relief by FEMA in 1998, served as a ‘pork barrel’ for corrupt mayors.

According to the public testimony of indicted businessmen, during the Rosselló administration the kickback practice was so common that it was dubbed ‘the tithe’. Such funds were laundered and passed on as campaign contributions to the then-ruling NPP. Thus, money laundering in Puerto Rico refers not only to cleaning up drug earnings but also to redirecting government funds to politicians and their associates. Between 1993 and 2000, the extortion, misappropriation, and laundering of public funds was such a well-organized business that a major local newspaper reported that a Grand Jury might be convened to indict the NPP under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act, the RICO Act.[lxix]

Conclusions

Puerto Rico’s political status is puzzling to most outside observers and many insiders as well. Even though Commonwealth represented an advance in self-government over the previous colonial situation, it did not eliminate the Island’s political and economic dependence on the United States. Although many legal rights and privileges have been extended to Puerto Rico, they are severely curtailed by the Island’s condition as an unincorporated territory that ‘belongs to but is not a part of the United States’. Lack of congressional representation, the incapacity of voting for the President, the inability to sign treaties with other nations, and unequal access to federally-funded programs are some of the problems flowing from the Island’s current status. Paradoxically, Puerto Rico is one of the most democratic countries in the Caribbean region, as measured by massive electoral participation, a competitive party system, and legal protection of individual rights and freedoms. But it is also one of the most undemocratic ones in the sense that Island residents are not fully represented in the federal government and international organizations that shape their everyday lives.

After reviewing the socioeconomic performance of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico over the full half century of its existence, we found that the government’s development strategies have relied heavily on tax exemptions and federal regulations as incentives for external investment. This approach limited the capacity for sustained growth of the Island’s economy, leading to a structural downturn in the mid-1970s from which it has never fully recovered. Low and inconsistent rates of economic growth in the last quarter of the twentieth century have resulted in high levels of unemployment and poverty. In turn, this situation has led to increasing reliance on federal transfers to maintain a standard of living higher than Latin American countries but lower than the poorest states of the United States.

Persistent poverty and unemployment are strongly correlated with high rates of crime and drug abuse. Puerto Rico has become both a large consumer of drugs and an international transshipment point from the Caribbean to the U.S. mainland. The ever increasing level of federal funds from a wide array of sources has resulted in high-level corruption around government programs and departments that rely heavily on such funds. Accountability systems seem to have failed given the frequency and volume of corrupt practices uncovered.

The Commonwealth’s most significant achievement over the past five decades has been the rising educational attainment of the Puerto Rican population. Because education has received a large portion of the government’s budget and a growing amount of federal funds, the Island’s labor force has become increasingly schooled and skilled. One of the most favorable aspects of the contemporary Puerto Rican situation is the high quality of its human resources. Unfortunately, for several decades after World War II, many Commonwealth planners and policymakers saw overpopulation as an obstacle to development and encouraged the relocation of ‘surplus workers’ abroad. Although this strategy helped to reduce unemployment and poverty rates on the Island, it expelled almost half of the population to the mainland. Ironically, Puerto Rico may now be experiencing the beginnings of a ‘brain drain’, with a growing proportion of professionals and skilled workers who move abroad.

Puerto Rican migration to the United States continues to be used as an escape valve for persistent unemployment and poverty. Massive movements of people to and from Puerto Rico will undoubtedly continue and probably increase during the first few decades of the twenty-first century. Deteriorating living conditions on the Island have already intensified the outflow of people to the mainland, similar in scale to the great exodus of the 1950s. At the same time, the return flow of Puerto Ricans is likely to persist, and perhaps intensify, as well as the constant circulation of people between the Island and the mainland. While Cuban immigration to Puerto Rico has practically stopped, Dominican immigration shows no signs of containment. It is foreseeable that smaller groups of people from other countries (such as Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina, and even China) will move to the Island. Should current trends continue, settlement patterns on and off the Island will become more mobile and diverse than ever before. Our analysis suggests that popular support for political nationalism tends to weaken with the constant transgression of national boundaries through large-scale migration and the emergence of a quasi-colonial form of government, in this case, the Estado Libre Asociado. Diasporic communities often develop different representations of identity from the dominant nationalist canon by stressing their broad kinship, cultural, and emotional ties to an ancestral homeland, rather than its narrow linguistic and territorial boundaries. This strategy is typical of long-distance nationalism.[lxx] Cultural nationalism will probably prosper more than political nationalism because the Puerto Rican population has become increasingly transnational in its residential locations, cultural practices, and values. Given the scant electoral support for independence and the difficulty of becoming the fifty-first state of the American union, the struggles for the expansion of citizenship rights, national identity, economic development, democratic representation, social justice, and security will most likely be advanced within the limits of the associated free state.

Notes

i. For the multiple implications of this legal expression, see Christina Duffy Burnett and Burke Marshall, eds., Foreign in a Domestic Sense: Puerto Rico, American Expansion, and the Constitution (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2001); Efrén Rivera Ramos, The Legal Construction of Identity: The Judicial and Social Legacy of American Colonialism in Puerto Rico (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2001).

ii. Aside from Puerto Rico, the other unincorporated territories of the United States are the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and American Samoa.

iii. Katherine T. McCaffrey, Military Power and Popular Protest: The U.S. Navy in Vieques, Puerto Rico (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2002), pp. 29-30.

iv. Tugwell, The Stricken Land: The Story of Puerto Rico (New York: Double Day, 1947).

v. According to José Trías Monge, who participated in the constitutional convention, the proposed bill of rights, ‘largely patterned after the Universal Declaration of Rights approved by the United Nations and the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, approved at Bogotá by the Organization of American States, was generally broader than the usual state constitution, a fact that created problems when the constitution was considered by Congress’. Trías Monge, Puerto Rico: The Trials of the Oldest Colony in the World (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1997), p. 114. The original version of the Commonwealth Constitution included the rights to work, free education, an adequate standard of living, and social protection in old age and sickness.

vi. Emerson, Puerto Rico and American Policy Toward Dependent Areas, The Annals of the American Academy of Political Science 285 (January 1953), p. 10.

vii. The phrase was coined during the Insular Cases of 1901, especially Downes v. Bidwell, in which the U.S. Supreme Court formulated the category of ‘unincorporated territory’ The current Dean of the University of Puerto Rico’s Law School, Efrén Rivera Ramos; former Secretary of Justice and Chief Justice of the Puerto Rico Supreme Court, José Trías Monge; as well as the Puerto Rican Chief Justice of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, Juan R. Torruellas, all agree that Puerto Rico remains an unincorporated territory, although each of them favors a different solution to Puerto Rico.s political status. See Rivera Ramos, The Legal Construction of Identity, p. 13; Trías Monge, Puerto Rico, especially chapters 10 and 11; and Torruellas, ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude: Puerto Rico.s American Century’, in Burnett and Marshall, eds., Foreign in a Domestic Sense, pp. 241-250.

viii. See United States-Puerto Rico Commission on the Status of Puerto Rico, Status of Puerto Rico (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1966), pp. 44-46.

ix. As an unincorporated territory, Puerto Rico is excluded from federal internal revenue laws.

x. United States-Puerto Rico Commission, Status of Puerto Rico, p. 12.

xi. Cited by Julio Muriente Pérez, La guerra de las banderas y la cuestión nacional: Fanon, Memmi, Césaire y el caso colonial de Puerto Rico (San Juan: Cultural, 2002), p. 46.

xii. Angel Israel Rivera, Puerto Rico: Ficción y mitología en sus alternativas de status (San Juan: Nueva Aurora, 1996), pp. 194-195.

xiii. See Nancy Morris, Puerto Rico: Culture, Politics, and Identity (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1995); Rodolfo de la Garza, Louis DeSipio, F. Chris García, John A. García, and Angelo Falcón, Latino Voices: Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban Perspectives on American Politics (Boulder, Co.: Westview, 1992).

xiv. The bibliography on Puerto Rican nationalism is voluminous, polemical, and growing. For a recent sampling, see Rafael Bernabe, Manual para organizar velorios (notas sobre la muerte de la nación) (San Juan: Huracán, 2003); Juan Manuel Carrión, Voluntad de nación: Ensayos sobre el nacionalismo en Puerto Rico (San Juan: Nueva Aurora, 1996); Luis Fernando Coss, La nación en la orilla (respuesta a los posmodernos pesimistas) (San Juan: Punto de Encuentro, 1996); Arlene M. Dávila, Sponsored Identities: Cultural Politics in Puerto Rico (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997); Jorge Duany, The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move: Identities on the Island and in the United States (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Nancy Morris, Puerto Rico; and Carlos Pabón, Nación postmortem: Ensayos sobre los tiempos de insoportable ambigüedad (San Juan: Callejón, 2002).

xv. For exceptions to this trend, see Juan Flores, From Bomba to Hip Hop: Puerto Rican Culture and Latino Identity (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000); Erna Kerkhof, Contested Belonging: Circular Migration and Puerto Rican Identity (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2000); Gina M. Pérez, The Near Northwest Side Story: Migration, Displacement, and Puerto Rican Families (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas, National Performances: Class, Race, and Space in Puerto Rican Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003); Carlos Torre, Hugo Rodríguez Vecchini, and William Burgos, eds., The Commuter Nation: Perspectives on Puerto Rican Migration (Río Piedras, P.R.: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1994); and Ana Celia Zentella, Growing Up Bilingual: Puerto Rican Children in New York (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1997).

xvi. Benedict Anderson, Long-Distance Nationalism: World Capitalism and the Rise of Identity Politics (Amsterdam: Center for Asian Studies, 1992); Nina Glick Schiller and Georges Fouron, Georges Woke Up Laughing: Long-Distance Nationalism and the Search for Home (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2001).

xvii. See Pérez, The Near Northwest Side Story; Ramos-Zayas, National Performances; and Nilda Flores-González, .Paseo Boricua: Claiming a Puerto Rican Space in Chicago., Centro: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies 13, no. 2 (2001), pp. 6-23. Many members of the Chicago-based Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN, National Liberation Armed Forces) prosecuted in the 1980s had been born and raised in the United States.

xviii. In the last plebiscite on the political status of Puerto Rico, held in 1998, only 2.5 percent of the electorate voted for independence. According to a 1993 poll, 3.5 percent of Puerto Ricans living in the United States favor independence. See Institute for Puerto Rican Policy, Characteristics of US-based Puerto Ricans by Status Preferences for Puerto Rico, IPR Datanote 15 (October 1993), p. 1.

xix. Here we draw on John Hutchinson, The Dynamics of Cultural Nationalism (London: Allen and Unwin, 1987).

xx. Puerto Rico has participated as a separate country from the United States in international sports events such as the Olympics since 1948 and in the Miss Universe pageant since 1952. On the implications of the victories by Quiñones and Trinidad, see Emilio Pantojas García, ‘La puertorriqueñidad en el nuevo discurso popular’, Diálogo (August 2001), p. 20.

xxi. Rivera Ramos, The Legal Construction of Identity.

xxii. (<http://factfinder.census.gov>).

xxiii. Letter to Jorge Duany, March 11, 2001. See also Linda Basch, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Szanton Blanc, Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States (New York: Gordon and Breach, 1994); Nina Glick Schiller, Linda Basch, and Cristina Blanc-Szanton, eds., Towards a Transnational Perspective on Migration: Race, Class, Ethnicity, and Nationalism Reconsidered (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1992).

xxiv. Peggy Levitt, The Transnational Villagers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

xxv. Zentella, Growing Up Bilingual.

xxvi. U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder, .Profile of Selected Social Characteristics: 2000. Puerto Rico. (<http://factfinder.census.gov>).

xxvii. The estimate is based on the difference between outbound and inbound passengers between the Island and the mainland, as reported by Puerto Rico’s Planning Board. Currently, U.S. immigration authorities do not keep statistics on population movements between Puerto Rico and the United States. The U.S. Census Bureau recently released much more conservative estimates of net migration: 126,465 persons for the 1980s and 111,336 for the 1990s. See Matthew Christenson, Evaluating Components of International Migration: Migration Between Puerto Rico and the United States (Population Division, Working Paper Series no. 64, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2001). To ensure the consistency of the data, we use the historical series compiled by the Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, Estadísticas socioeconómicas (San Juan: Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, 1972-1989), and ‘Movimiento de pasajeros entre Puerto Rico y el exterior. Años fiscales 1990-2000’. (unpublished manuscript, Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, Programa de Planificación Económica y Social, Subprograma de Análisis Económico, 2001).

xxviii. Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, .Migración de retorno en Puerto Rico., in Informe económico al Gobernador, 1999 (San Juan: Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, 2000), pp. 1-16; Luz H. Olmeda, .Aspectos socioeconómicos de la migración en el 1994-95., in Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, Informe económico al Gobernador, 1997 (San Juan: Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, 1998); and Duany, The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move, p. 223.

xxix. Ibid.

xxx. See Samuel Martínez, .Identities at the Dominican and Puerto Rican Migrant Crossroads., in Shalini Puri, ed., Marginal Migrations: The Circulation of Cultures in the Caribbean (London: Macmillan, 2003), pp. 141-164.

xxxi. In addition, an unknown number of Dominicans has entered Puerto Rico illegally. In 1996, the Immigration and Naturalization Service estimated that 34,000 undocumented U.S. Census Bureau, American Fact finder, Census 2000. immigrants, mostly Dominicans, were living in Puerto Rico. See ‘INS: Methodology and State-by-State Estimates’, Migration News, March 1997.

xxxii. Carmen Gautier Mayoral was the first to argue that federal transfers and regulations constitute the ‘permanent but wobbly legs’ of the Commonwealth.s economy. See Gautier Mayoral, The Puerto Rican Socio-Economic Model: Its Effect on Present Day Politics and the Plebiscite, Radical America 23, no. 1 (1989), pp. 21-34.