Punishment And Purpose ~ Appendix 1~ 4

Appendix 1. Vignettes

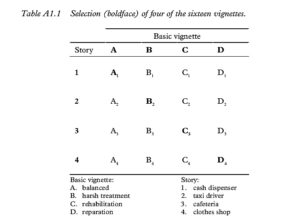

The boldface vignettes in Table A1.1 are included in this appendix

Table A1.1

A1. Robbery at a cash dispenser: balanced

Late in the evening, a man is taking money from a cash dispenser in the hall of a bank when he is suddenly grabbed and punched in the face. He sees before him a man with a black nylon stocking on his head and a gun in his hand. The offender tells the victim to take NLG 1,000 from the cash dispenser for him, otherwise he will shoot. The victim panics, and starts to shout and hit out wildly. This causes the offender, Johannes Cornelis Vrugink, such consternation that he takes from the machine the NLG 150 that the victim had already requested and runs away. In all the commotion he forgets to remove the nylon stocking from his head.

One street away, two police officers on their beat stop Vrugink, who is still wearing the stocking on his head. When Vrugink tries to run away, the officers grab hold of him and then search him. In his pocket the officers find a toy gun, which has been painted black, and NLG 150. Vrugink is taken back to the station and questioned. At first Vrugink denies any wrongdoing. Soon after the arrest, however, the victim arrives to report the offence. When Vrugink is confronted with the information provided by the victim, he finally admits to the offence. The toy gun, the nylon stocking and the NLG 150 are seized. Vrugink is kept in custody for another three days and then released.

The victim is a 40-year-old man. He is married with two children. Immediately after the offence he went to the hospital’s casualty ward. His nose was found to be broken and he received treatment. His glasses, worth NLG 600, were destroyed by the punch. The victim says that being threatened by the (toy) gun has traumatised him. He was on sick leave for two months after the offence. Now he is still fearful, particularly out of doors. He has trouble sleeping and finds it very difficult to concentrate at work. The victim is not party to the action, but is present at the trial.

Nineteen-year-old Johannes Cornelis Vrugink is unmarried and at the time of the trial has been living with his girlfriend, also 19 years old, for several months. Vrugink previously lived from the age of 16 with his uncle, after running away from home because of continuing problems with his stepfather. After primary school, Vrugink attended but did not complete the LTS (junior technical school). He has had a number of jobs through an employment agency but kept leaving them because he found the work too dull, had difficulty getting up on time in the morning, and usually argued with his employers. Vrugink has trouble dealing with conflict situations. He says that out of boredom he ‘smokes a lot of dope’ and gambles regularly. These activities cost a great deal of money. There are no further indications of addiction to hard drugs. Vrugink committed the offence because of a chronic lack of funds and in order to have money to impress his friends. Vrugink was unemployed at the time of the offence. He receives income support and is following a professional driving course. He is in the process of setting up his own transport business, with the help of his employment agency.

Vrugink is present at the trial. When allowed a final word, he says that he wants to dedicate himself fully to making a success of his business and keeping on the straight and narrow so that he can lead a normal life with his girlfriend. He tells the victim that he deeply regrets his acts and wants to change his lifestyle.

The judicial documentation shows that when Vrugink was 18 years old he received a magistrate’s fine of NLG 200 for assault. At 17 years old, Vrugink spent two months in a youth custody centre for robbery. He has also been involved with the law in connection with vandalism and shoplifting. No sentences were passed in these cases.

B2. Robbery of a taxi driver: harsh treatment

Late in the evening, a taxi is parking in an empty taxi rank when suddenly a man wearing a balaclava on his head jumps into the car. The offender, Andreas Doncker, shows a gun and says that he will use it unless the driver hands over his wallet with the day’s takings. When the victim fails to react immediately, Doncker punches him in the face and says that it would be wise to do as he is told. The by now terrified driver hands over his wallet, containing over NLG 1,000. Doncker tells the driver to stay in his taxi for the next half-hour and not to drive anywhere. Doncker then jumps out of the taxi and runs away. As soon as Doncker is out of sight, the driver reports the offence to the police on his radio’s emergency channel. On the basis of the victim’s description of Doncker’s clothes, two officers apprehend Doncker in the street half an hour later. When Doncker tries to flee, the officers wrestle him to the ground. They search his clothes and find a loaded automatic gun, a wallet with over NLG 1,000 and a balaclava. Doncker is taken to the police station for questioning. Under questioning he admits to the offence. He says that he once bought the gun in Belgium for self-defence. The money, the balaclava and the automatic gun are seized. Doncker is held for another six days before being allowed home. The victim is a 42-year-old taxi driver. He is married with one child. The punch gave him a black eye. He was too scared to drive his taxi for three months after the offence. Now he is still fearful, especially out of doors, and he has trouble sleeping. The victim is not party to the action and is not present at the trial.

Twenty-seven-year-old Andreas Doncker is unmarried and has lived on his own since he was 17 years old. After primary education Doncker attended the MAVO (school for lower general secondary education), but left without completing his schooling there. He then attempted a number of months at the LTS (junior technical school), but gave up on that too. He has had short spells of employment with various cleaning firms, but these never lasted long. Doncker is long-term unemployed and receives income support, most of which is spent on going out and smoking marihuana.

When he goes out he ‘easily’ drinks 25 glasses of beer and spends the whole of the next day in bed. There is no question of hard drugs use. Doncker says that he committed the offence because of lack of money. His income support was not sufficient to maintain his lifestyle. When allowed a final word in the trial, he says that he is sorry and that he does not know what else to say.

Doncker’s judicial documentation shows that as a minor he was involved with the law on a number of occasions for various theft cases. When he was 16 he also spent four months in a youth custody centre for robbery. When he was 22 the magistrate sentenced him by default to three months in jail for aggravated theft. He served this sentence. Since then he has been involved with the law in connection with other theft and assault cases. No sentences were passed in these cases.

C3. Robbery at a cafeteria: rehabilitation

Late in the evening, when the last customer has left, the owner of a cafeteria is just about to close his shop when a young man walks in. Before the owner can say that the cafeteria is closed, the young man gives him a hard shove. This causes the owner to fall to the ground. The offender, MariusDiepenveen, warns the victim not to get up. Diepenveen quickly opens the till, takes out NLG 250 and runs out of the cafeteria.

The driver of a taxi parked nearby sees Diepenveen run out of the cafeteria and goes inside to investigate. He finds the victim, who tells him what has happened. Together they drive to the police station to report the offence. The taxi driver believes that he has recognised Diepenveen because two days earlier he had picked him up in his taxi in a drunken state and driven him home.

A patrol car is sent to Diepenveen’s flat, following the taxi driver’s directions. After a while Diepenveen arrives. The officers stop him and ask what he has been doing that evening. When Diepenveen tries to run away, he is arrested and taken to the police station. Diepenveen is found to be drunk. He is questioned the following morning after sleeping off the alcohol in a cell. At first Diepenveen maintains that he has done nothing wrong. He only admits to the offence when the officers propose a confrontation with the victim. Diepenveen says that he used part of the NLG 250 to pay off a debt owed to an acquaintance from the pub. He does not know the name of this acquaintance. He spent the rest of the money that evening on drinking and gambling with his friends. He had already drunk 10 glasses of beer when he committed the offence. Diepenveen is charged and then released.

The victim is the 47-year-old owner of a cafeteria. He is unmarried, and lives with his girlfriend and her child. While reporting the offence at the police station he complained of shooting pains in his lower arm. Diepenveen’s shove had caused him to fall badly. After giving his statement he was taken to hospital. His wrist was found to be broken and he was allowed home that evening with his wrist in plaster. The victim is not present at the trial and is not party to the action.

Nineteen-year-old Marius Diepenveen is unmarried and lives alone. He has a steady girlfriend, whom he sees on average three times a week. He is unemployed and receives income support. At the time of the offence he was going out nearly every evening. Most of his income support is spent on drinking and gambling. Diepenveen says that he committed the offence because an ’acquaintance’ from his nightlife to whom he owed money was pressurising him and because he had no money for going out.

A probation report provides the following information. Diepenveen is an only child. When he was nine years old, his mother was killed in a road accident. Until he was 17 he lived with his father, a truck driver, who was hardly ever home. When his father was at home, the two would usually argue and Diepenveen would be beaten by his father. The situation became untenable when Diepenveen turned 17, and he went to live on his own. He has had no contact with his father since. The highest educational qualification that Diepenveen attained is primary education. He spent a couple of years at the LTS (junior technical school), but often played truant and did not complete his schooling there.

Diepenveen’s incomplete schooling and unhappy family situation have caused his personal development to lag significantly behind that of his peers. He is a very impulsive spender and is quick to argue with anyone who disagrees with his point of view. He gambles more from boredom than from addiction. If he keeps drinking as much, however, he will risk alcohol addiction. Diepenveen does not use hard drugs.

The probation report finally indicates that Diepenveen’s unstructured and uninhibited lifestyle and his association with the wrong kind of friends are important factors in causing his behaviour to deviate. Diepenveen seems sincere when he says that he has had enough and wants to change. At the time of the offence Diepenveen had just started as a trainee plasterer with his uncle who is a building contractor. He says that he has finally found something he enjoys doing and that he is keen to complete his plastering training. When Diepenveen’s training is completed, his uncle will give him a job.

When Diepenveen is allowed a final word at the trial, he says that he is full of remorse for his act and shocked that his victim’s wrist was broken. He wants to work hard to earn his money honestly and to lead a normal life. When he has succeeded in that, he wants to move in with his girlfriend. Diepenveen has been involved with the law once before. When 18 years old, he was sentenced by the magistrate to a NLG 400 fine for a series of shoplifting offences.

D4. Robbery at a clothes shop: reparation

Late on a Friday evening, after late night shopping, the owner of a clothes shop is ready to leave his shop. After closing up, he has spent a couple of hours rearranging the shop window. When walking to the counter to pick up his keys and wallet, he hears someone behind him entering the shop. Before he can even turn around to say that the shop is closed, he is grabbed by the coat and thrown to the ground. The attacker, Frans Willem Paakes, kicks the shopkeeper in the chest as he lies on the ground and shouts some abuse at him. Paakes then takes the shopkeeper’s wallet, removes NLG 200 and leaves the shop. When he has recovered from the shock, the victim goes to hospital because his chest is very painful. Police officers come to the victim’s house in the morning to take his statement. He says that his ex-brother-in-law, Paakes, was the offender.

The officers go to Paakes’ house, following the victim’s directions. Paakes is found to be home and is taken to the station for questioning. Paakes admits to the offence and says he was planning to give himself up to the police that day. He tells the officers that the victim until recently had been in a relationship with his younger sister. Paakes never liked the victim. When the victim had thrown Paakes’ sister out on the street after a screaming row and had also broken some of her belongings, Paakes had been furious.

Paakes had drunk a great deal on the evening of the offence. When passing by his ex-brother-in-law’s shop he had entered on impulse and committed the offence. Paakes was allowed home after being charged. The victim is Paakes’ 26-year-old ex-brother-in-law. When Paakes threw him to the ground, his jacket, worth NLG 500, was irreparably torn. The kick to his chest broke one of his ribs and he had to spend six weeks at home recuperating. The victim is not party to the action, but is present at the trial.

Frans Willem Paakes is 29 years old. He is married and has a two-year-old daughter. After completing the LTS (junior technical school), Paakes was employed by an electrical contracting company. He has risen through the ranks over the years and now has a management position in the company. This gives Paakes and his family a good standard of living.

On the night of the offence, Paakes had drunk a great deal with a couple of friends. He tends to do this on Friday evenings. On the way home he passed by his ex-brother-in-law’s shop. At the trial Paakes says that he does not know what possessed him but in an impulsive fit of rage he attacked his victim. Paakes considers neither his drunkenness nor the fact that he has never liked his ex-brother-in-law to excuse his actions that night. When Paakes is allowed a final word, he says that he has always been very protective towards his younger sister but that this should never have happened. This is the first time that Paakes has been involved with the law.

**************

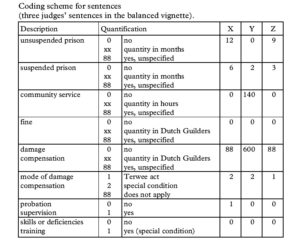

Appendix 2. Coding of sentences

Examples of three judges’ sentences in the balanced vignette

judge X: 18 months imprisonment of which 6 months conditional with an operational period of two years and probation supervision and damage compensation as special conditions.

judge Y: 140 hours of unpaid work instead of 3 months imprisonment. 2 months conditional imprisonment with an

operational period of 2 years. Special condition NLG 600,– damage compensation.

judge Z: 12 months imprisonment of which 3 months conditional with an operational period of 2 years and the measure of damage compensation.

Coding scheme for sentences (three judges’ sentences in the balanced vignette).

**************

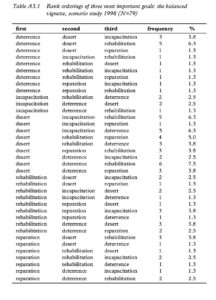

Appendix 3. Rank orderings of goals of punishment

Table A3.1 Rank orderings of three most important goals: the balanced vignette, scenario study 1998 (N=79)

Table A3.2 Rank orderings of three most important goals: the harsh treatment vignette, scenario study 1998 (N=77)

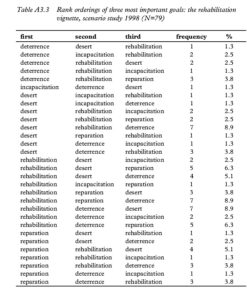

Table A3.3 Rank orderings of three most important goals: the rehabilitation vignette, scenario study 1998 (N=79)

Table A3.4 Rank orderings of three most important goals: the reparation vignette, scenario study 1998 (N=78)

***************

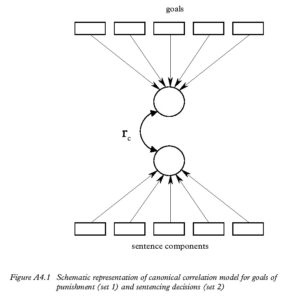

Appendix 4. Canonical correlation analysis in the scenario study

Canonical correlation analysis creates linear composites, called canonical variates, for each set of variables in such a way that the canonical variates representing each set are optimally correlated. The correlation between two canonical variates is called the canonical correlation coefficient (rc). The squared canonical correlation represents the overlapping variance of a pair of canonical variates. After the first pair of canonical variates has been calculated, the analysis proceeds with the calculation of the next pair of variates which are uncorrelated with the first. This procedure is continued until no more variance is left (cf. principal components analysis). As such, the canonical variates partition the association between the two sets of variables additively (Stevens, 1996). Only significant canonical correlations are interpreted (significance testing of canonical correlation coefficients is achieved through a residual test procedure resulting in the test statistic Bartlett’s V which is distributed as χ2). This is an important feature of the technique since it enables different patterns of association between different subsets from both types of variables to be analysed. While the first pair of canonical variates represents the most important (i.e., strongest) patterns of association between goals and sentence components, subsequent pairs of variates, if significant, may show meaningful complementary patterns of association between the two sets.

Canonical correlation analysis does not require the original variables in the two sets to be normally distributed, although the analysis is enhanced if they are (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996; Thompson, 1984). For this reason, several models for each vignette are presented in which the original variables have been treated (i.e., coded) differently. Correlations between the original variables in a set and the canonical variate for that set are employed for interpretation. These are called ‘structure correlations’ (Tacq, 1992). The structure correlations should be greater than 0.30 to be considered for meaningful interpretation (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996).

The analysis is symmetrical which means that the technique itself does not assume nor indicate causal relations between the variables. On theoretical grounds, however, it is not uncommon to include notions of causality in the interpretation. For this type of interpretation ‘redundancy’ is examined. Redundancy is defined as the variance that a canonical variate from one set extracts from the variables in the other set. Because the interest in our scenario study lies primarily in determining whether clear and consistent patterns of association exist between goals of punishment and sentencing decisions, conditional proposition 3 implies examining redundancy in both directions: ‘if preferred goals of punishment are rele vant for choosing a particular sentence or if a sentence is consistently rationalised by a preferred goal or combination of goals.’ The general model of canonical correlation analysis for the two sets of variables in the scenario study is shown in Figure A4.1.