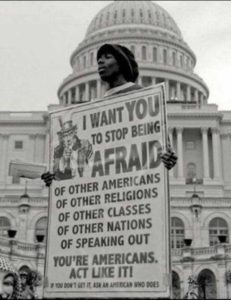

Photo: youtube.com

Participatory economics has long been proposed as an alternative to capitalism and centralized planning. It remains, nonetheless, a misunderstood concept and continues to find opposition among both capitalists and anticapitalists. So, what exactly is “participatory economics” and how does it fit with the socialist vision of a classless society? In this interview, Michael Albert, founder of Z Magazine and one of the leading advocates of the movement toward a “participatory society” addresses key questions about capitalism, socialism and the implications of a participatory economy.

C.J. Polychroniou: Any discussion of economic systems revolves essentially around two apparently opposed poles — capitalism and socialism. In reality, however, most of the actually existing economies in the modern world have been “mixed economies.” Be that as it may, what’s your understanding of capitalism, and what are the distinguished features of socialism?

Michael Albert: Capitalism is an economic system in which people own workplaces and resources, employ workers for wages to produce outputs and overwhelmingly employ market allocation to mediate how the outputs are dispersed. Typically also, and I would say inevitably if it has the first two features, it will also have what I call a corporate division of labor in which about 80 percent of the workforce does overwhelmingly rote, obedient and mainly disempowering tasks, and the other 20 percent monopolizes empowering tasks. Income will be a function of property and bargaining power.

In my view, there are, therefore, three main classes in capitalism: a working class doing the disempowering work [whose members] have low income and nearly no influence; a capitalist class that employs workers, sells their product and tries to reap profits, and which, due to those profits, enjoys tremendous wealth and dominant power; and a coordinator class situated between the other two, doing the empowering work, and, due to that, having the power to accrue high income and substantial influence.

Socialism is trickier to pinpoint. For some it is an economy in which those who produce decide all the outcomes, so it is classless, or, if you like, has only one class, the workers, all of whom have the same overall economic status. For others, socialism is a society with a polity that greatly influences economic outcomes on behalf of the public, even while owners still reap profits. For still others, socialism is an economy that has public or state ownership plus central planning or markets for allocation.

I think this last is what socialism in practice has been, plus having a corporate division of labor that arises inexorably due to its forms of allocation but is also preferred, plus an authoritarian polity. However, I call this type of economy “coordinatorism” for the clear and obvious reason that its institutions eliminate capitalist ownership but elevate the 20 percent coordinator class to ruling status. Out with the old boss: the owner, the capitalist class; in with the new boss: managers, doctors, lawyers and so on, the coordinator class.

So, if you like socialism because you hope for classlessness, you are pretty likely nowadays to have in mind some kind of worker-controlled economy but typically without offering clarification of what institutions can deliver that.

If you don’t like the idea of full classlessness — either fearing that it would be dysfunctional or wishing to maintain coordinator class advantages — as socialism, you likely have in mind some variant on classical Marxist coordinatorist formulations.

I prefer classlessness — which, in my mind, is like preferring freedom to servitude — but I also see a need to have an institutional vision able to give it substance, which is what participatory economics, or if you prefer, participatory socialism tries to provide.

“Actually existing socialism” failed because, to a large extent, it was an authoritarian political system, the economy was guided from above, and social and cultural freedom was dictated from party apparatchiks. In your view, was this system salvageable, or was its downfall inevitable and necessary?

The latter, but I would like to clarify the picture just a bit.

I don’t think “actually existing socialism” had an OK economy, for example, that was made unacceptable by a repressive or authoritarian state. I think “actually existing socialism,” or “20th-century socialism” or socialism as it is outlined in almost every serious scholarly presentation that goes beyond just positive adjectives, includes either markets (sometimes), or central planning (more often), a corporate division of labor, remuneration for output or bargaining power and some other less critical economic features. Then, in an actual country, it must, of course, also have an associated political system, kinship arrangements, cultural institutions and so on. And yes, those latter will all have to be at least compatible with the economic features or the society will be in turmoil, and one political arrangement strongly consistent with a central planning “actually existing socialism” model, is an authoritarian government.

So the best version of this socialism would be market allocation, public ownership and a parliamentary government. The worst version would be centrally planned allocation, state ownership and an authoritarian government or outright dictatorship. But again, the problem with the economics of both these options is not that it is neutral or good and only made bad by other institutions imposing. The economic aspects are intrinsically bad. They intrinsically elevate a coordinator class above workers, rather than generating classlessness.

In any contemporary discussions of alternative economic systems, there is considerable emphasis on the need for participatory economics. What exactly is participatory economics, and does it fit under both capitalism and socialism?

Participatory economics proposes just a few key institutions for a new way of conducting economics. It starts with worker- and consumer-councils as decision-making bodies and elevates the idea that each participant in economic life should have a say over outcomes in proportion as they are affected by them — which it calls “self-management.”

It then proposes a new way to define jobs to generate a new division of labor, which is called “balanced job complexes.” This combines tasks into jobs so that each person working in the economy does a mix of tasks in their daily labors such that the “empowerment effect” of each worker’s situation is equal to that of every other worker’s situation, which eliminates the basis for a coordinator-class/working-class division.

Next, participatory economics proposes a new equitable basis for earning income. Instead of our incomes being determined by property ownership, bargaining power or even the value of our product, it should derive only from how hard we work, how long we work and the onerousness of the conditions under which we work at socially useful production.

And finally, participatory economics utilizes participatory planning instead of markets or central planning. Markets and central planning are horrendously destructive of equity, ecological sustainability, sociality and people’s ability and even inclination to control their own lives — and also entirely contrary to our other positive aims, noted above. In contrast, participatory planning is a process of collective negotiation of inputs and outputs in light of their full social, personal and ecological costs and benefits. The process has no center, no top, no bottom and conveys self-managing say to all participants. It literally augments rather than destroys solidarity, diversity, equity and collective self-management.

Of course, the above very condensed presentation of participatory economics isn’t enough to be compelling, nor does it address issues of attaining the goal, but perhaps it at least suggests that this alternative bears attention. There are many places online and in book-length presentations, videos and the like to look to see more, so one can more fully assess for oneself.

Does participatory economics support or undermine private property?

Of course, in a participatory economy, you would still own your shirt, and countless other such items. Your phone is yours. Your violin is yours, and so on. But I assume you are referring to people owning means of production like natural resources, assembly lines, the tools used in workplaces and the workplaces themselves, and participatory economics doesn’t really support or undermine that — it literally totally eliminates it.

Participatory economics institutions simply do not involve any of the aspects of private ownership of productive profits. There are no profits since income is only for duration, intensity and onerousness of socially valued labor. There is no personal control of asset use since decisions are made via collective self-management. If Joe actually had a deed to a workplace in a participatory economy, it would give Joe precisely zero returns — material, organizational or social — so, of course, such deeds will not exist.

What do you envision to be the role of the state under participatory economics?

There is a parallel vision, if you will, of participatory politics. Stephen Shalom and I are key proponents of this vision of a future polity operating alongside a participatory economy. This polity would still legislate laws for the population, adjudicate disputes, handle various kinds of security issues and deal with various “executive” matters of implementation. For example, it would oversee the Centers for Disease Control, since it would need some special executive powers not common to less governmental and solely economic institutions — but it would also operate like other workplaces, of course.

In each case, there would be major changes, not least due to having participatory economic relations in the structure of government institutions and in their purposes and agendas.

If you think of the economy and the polity — and kinship and culture too — as being like schools that impact the lives and views of their participants, it becomes clear why they must be compatible. It would be dysfunctional and disruptive to have the polity producing people with values, habits and expectations contrary to those which the economy they must engage with needs to operate, just as it would be dysfunctional and disruptive to have an economy producing people with values, habits and expectations contrary to what the polity they must engage with needs to operate.

It is not for us to decide future people’s daily lives. It is for us to deliver to future people a set of institutions that let them make those decisions themselves.

Assuming that participatory economics is feasible and widespread within a given social formation, what model of democracy would be appropriate for this type of an economy?

Political participatory self-management, which is a set of nested assemblies (neighborhood, county, state and national) that become the primary seat of government legislative and executive decision-making. They are organized to deliver influence to individuals and constituencies in proportion as they are affected.

Workers’ cooperatives are spreading in various parts of the world, with certain regions of Spain and Italy having developed rather extensive networks of cooperative enterprises. Are such developments consistent with the type of participatory economics that you advocate?

Yes, but there are also pitfalls possible. That is, when workers take over a plant, their act is potentially moving toward a participatory economic future. Even more so if they make their income policies equitable. Still more so, if they institute balanced job complexes. And finally, yet more so, if they start to override market pressures by negotiating just outcomes with other units and consumers.

On the other hand, if they retain the old corporate division of labor, then in time, a coordinator class will dominate outcomes and dissolve their other achievements. This points up the importance of institutional choices. What we want matters greatly, of course. But so do the arrangements we adopt. If we want classlessness, for example, but we adopt a corporate division of labor and/or markets or central planning, those choices will overcome our good intentions.

Does a desire to attain participatory economics in a participatory society have any implications for the present?

To win a new society, what we choose to do in the present has to lead toward what we want for the future: we must plant the seeds of the future in the present.

Wanting participatory economics means we want classlessness and we want some very specific defining institutions. Our own organizations should therefore reflect these desires, move us toward them and be consistent with arriving at them.

This is easier said than done. Sometimes we create a political institution with participatory intentions that then devolves toward authoritarian results. Or we develop a movement against capitalist profit-seeking, but we make it top-heavy with coordinator class leadership and values, and so we wind up not with participatory economics, but with our movement either unravelling due to insufficient worker support (due to workers being alienated by the movement’s coordinator bias) or with our movement winning a coordinatorist economy, but not participatory economics.

In each institution, we must ask: How should decisions be made? How should work be divided among participants? How should remuneration be organized? And how should the organization relate to other organizations? Participatory economics provides norms and aims for each of these choices.

One more point on this. If a particular set of aims becomes prominent on the left, this implies it will impact various decisions and choices in the present. When movements going into the late sixties became collectively explicitly committed to reducing and eliminating racism and sexism in society, it meant that movement organizations and projects could no longer have racist and sexist internal roles and allotments of tasks. This was, of course, positive but also no small implication and actually engendered considerable turmoil with established whites and men reticent, shall we say, about the changes, and the task isn’t even fully resolved to this day.

My point is, the same kind of dynamic would follow from participatory economics becoming a shared guiding priority for movements. It would mean that movement organizations and projects could no longer have classist internal roles and allotments of tasks — but in this case, that would mean they would have to become collectively self-managing and have to have all participants able to fully contribute, which would in turn mean adopting balanced job complexes. But that transformation would mean people who currently dominate our projects and movements would have to become participants like all others, something they would not all welcome, partly for reasons of simple class interest trying to block a decline in personal income and influence, and partly sincerely believing that it would harm the projects.

So people who run left institutions have deep and powerful reasons to want to prevent participatory economics from becoming a widely shared aim since, if it did, that would lead in relatively rapid time to a kind of revolution within the left, not unlike the sexual and racial revolutions within the left, but this time about class — and not anti-owners, but about eliminating the class hierarchy between workers and coordinators, which would mean implementing balanced job complexes. This dynamic within left media makes it hard for participatory economics to get a wide and serious hearing.

One final question: What type of economic policies do you think will be implemented by the Trump administration?

I think he actually probably does want to do major infrastructure overhaul, but, other than that, and as a higher priority, he wants to elevate corporate dominance of government policy even further than what already exists, and, most devastating, he wants to ignore and even worsen global warming and other similar potentially devastating ecological trends.

How successful this all is will depend, of course, on how unrelenting his opposition will prove to be. Progressives and radicals must amass the strongest and most sustained possible opposition across all relevant constituencies.

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for concision.

Copyright, Truthout.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, the political economy of the United States and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published several books and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Croatian, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish.

One of the basic principles of democracy is “one person, one vote”. Other criteria for an efficient and robust model of democracy include an informed and critically inclined citizenry and the presence of a political culture catering to the “common good” instead of the self-centred whims and boundless greed of the rich and powerful.

One of the basic principles of democracy is “one person, one vote”. Other criteria for an efficient and robust model of democracy include an informed and critically inclined citizenry and the presence of a political culture catering to the “common good” instead of the self-centred whims and boundless greed of the rich and powerful.