Introduction

Introduction

Both left-wing and right-wing parties and movements claim to defend Western Values while demonstrating against Islam or against Islamophobia and Populism. From both sides we hear words like Liberty and Equality. Both sides are pointing to the Enlightenment as the core of European Values. When defending ‘European Civilisation’, everyone points to the French Revolution and its Manifesto, the Declaration of Human Rights. The French struggle against privilege, for equal political rights was the start of the political emancipation of the citizens that after 1789 spread all over Europe.

I think we all agree that the legacy of the French Revolution is worth to be defended, but there is a new struggle going on about its Interpretation: do the European Values come in a ready-made package, to be accepted and implemented by the whole world or at least by everyone coming to Europe? Or is the French Revolution still an unfinished business and do we still have to struggle for the realisation of equality and liberty in our societies? I would like to show you why I am of the opinion that the latter is the case, by looking more closely into the heritage of this project for liberty and equality from the 18th century.

I will do so, using a text of the German thinker Karl Marx. (Trier, 5 may 1818 – Londen, 14 march 1883) He is mainly known for his economical ideas about Capital and Labour, but his political texts are in no means less insightful.

If you want to know how equal and free a society is, it is always a good idea to look at the rights of those who are looked upon as ‘different’ from everybody else. Those who claim equal treatment because they are being discriminated against. Marx does exactly this. He addresses an issue that was debated fiercely during the 19th century, just like it is today. I am talking about the relation between State and Religion. Back then the big issue was the position of Jews in society. The state was not secular, but Christian, and Jews were second-class citizens with less rights than our minorities have now. Things are different today, but we can still recognize the questions of the 19th century: does Jews have to renounce their religion in order to obtain full citizenship? Are Jews a threat to society because of their different customs and religious practices? Today, we would never pose these questions in relation to Jews. But they are openly discussed in relation to Muslims.

Marx, of Jewish origin himself, intervenes in 1843 in the debate, publishing the essay Zur Judenfrage. On the Jewish Question, is written 24 years before Capital. In this text, he laid a fundament for his later work. The text is a polemic reaction to an earlier article called Jewish Question from Bruno Bauer, who belonged to the same philosophical-political group as Marx, the Hegelians.

His first point, which is crucial, is a change of perspective: while discussing the Jewish Question, do not look at the behaviour and aspirations of the Jews, but look at the role of the State. Marx uses the Jewish Question to analyse the mechanism of political emancipation in a modern society. In this endeavour, the criticism of religion is the condition of a criticism of politics.

Criticism of religion: what religion and political emancipation have in common

What are we talking about? We are talking about human rights. We have to realise that the original Declaration from 1789 was called Declaration of the rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen) In 1948, when the UN adopted the Declaration it became the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Citizen disappeared.

That is striking, since the core of the analysis by Marx lies in the difference between ‘Man’ and Citizen’. In his words, between emancipation as such and political emancipation. By letting the Man and the Citizen fuse into the Human, an essential procedure of political emancipation is covered up. Who is this ‘Man’ in the Declaration?

Niemand anders als das Mitglied der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft. Warum wird das Mitglied der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft ‘Mensch’, Mensch schlechthin, warum werden seine Rechte Menschenrechte genannt? Woraus erklären wir dies Faktum? Aus dem Verhältnis des politischen Staats zur bürgerlichen Gesellschaft, aus dem Wesen der politischen Emanzipation. (p.363-364)

The ‘Man’ in the Declaration is not the universal Human Being, it is a very real, tangible person – and yes, in the original declaration it was a man! – someone who makes a living in everyday- society. Mostly, it is the homo economicus, the merchant that had done well, but did not have the political rights the nobility had. This ‘Man’ was the driving force behind the French Revolution. The word Marx is using for this real person, is bourgeois. I will use this word from now on. The citoyen (French for citizen), on the other hand, is the member of society in its political function. The citoyen represents the political rights of the bourgeois. By differentiating between the two of them, a separation, or even a schism, is created in the human being itself. This separation is necessary to be able to talk about political rights, but it still has this effect of a division within the human being. The consequence of this is that the very character of political emancipation is alienation. The similarity between the character of religion and the character of political emancipation is precisely this: alienation.

Die Religion ist eben die Anerkennung des Menschen auf einem Umweg. Durch einen Mittler. Der Staat ist der Mittler zwischen dem Menschen und der Freiheit des Menschen. Wie Christus der Mittler ist, dem der Mensch seine ganze Göttlichkeit, seine ganze religiöse Befangenheit aufbürdet, so ist der Staat der Mittler, in den er seine ganze Ungöttlichkeit, seine ganze menschliche Unbefangenheit verlegt. (p.353-354)

This is the relation between State and Religion according to Marx: they both recognize the Human Being only in a roundabout way, thus alienating man from himself. This self-estrangement has to be unmasked and criticized. Marx turns Feuerbachs criticism of religion into a critique of the modern state. Alienation does not only exist with regard to religion, it is also part of the much-praised political emancipation. In that sense criticism of religion is the condition of all criticism, as Marx states in the Introduction of his ‘Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right’, which was written a year after On the Jewish Question.

In this Introduction he talks about the transformation of the criticism of Heaven (religion and theology) into a criticism of Earth. This is not an easy, straight- forward procedure. Heaven and Earth do have a complex dialectical relationship. Marx unmasks religion as earthly and the political state as religious. The Dutch theologian Arend van Leeuwen (1972, p. 175)has formulated this dialectical relationship as follows:

The criticism of Heaven is the condition of the criticism of Earth; The criticism of Earth is the fundament of the criticism of Heaven.

To have a better understanding of this procedure we will read two extracts from On the Jewish Question from 1843. In the first, Marx develops his proposition about the separation between the human being and the citizen, in the second, he speaks about the religiosity of the political state.

Extract 1: the alienation between human being and citizen. (369-370)

This extract is about three topics:

– The relation between political emancipation and the emancipation of Jews.

– Marx’criticism of political emancipation

– The difference between political emancipation and human emancipation.

Marx essay is a response to an article of Bruno Bauer, who represents a view that is still often heard: the best reaction to the tension between state and religion is the suppression of religion. For Bauer, emancipation, or the acquisition of equal rights, is only possible if believers – Jews in this case – renounce their religion. Real political emancipation means the end of religion. So the vital question for Bauer is: how to get rid of religion?

Surprisingly, Marx does not agree with Bauer. He thinks Bauer is mistaken by confusing political emancipation with human emancipation. Political emancipation does not yet emancipate human beings from religion. Marx points to the United States as proof: the only secular state in his time was still very religious. We could point to our own societies as well to support Marx on this. Marx does not agree with the idea still living with a lot of liberals and socialists or social democrats, that the veritable modern society is a society without religion.

According to Marx, political emancipation means that the state is secular, not having a religious attitude with regard to religion. The same goes for all other social elements.

Den Widerspruch des Staats mit einer bestimmten Religion, etwa dem Judentum, vermenschlichen wir in den Widerspruch des Staats mit bestimmten weltlichen Elementen, den Widerspruch des Staats mit der Religion überhaupt, in den Widerspruch des Staats mit seinen Voraussetzungen überhaupt. (p.352-353)

Political Emancipation means that the State maintains political relations with all particular elements in society. The State has become a Public Affair, representing the common good. Not one particular element is favoured. The principle of equality is at the heart of political emancipation.

But: this doesn’t mean that these particular elements stop to exist. The private realm is very real: property, family, labour. To be able to represent the common good, the state has separated itself from society. It does not represent the interests of one group in particular, like the Christians, the Richs or the Nobility, but it represent the general interest. This means that the private is no longer political, but it still constitutes the precondition for the State. Without the private, there would be no State.

The State has abstracted itself from the real existence of its citizens and the citizens have handed over the political function to the state. As a consequence, the individual is split into two beings: one is the very real and particular member of the civil society (bourgeois); the other is abstract and political: the citizen. (citoyen)

Bauer does not see this cleavage, and that is why he is expecting something from the State that it cannot do: realising human emancipation, since it has only power over the political domain. That is: Marx thinks it is a delusion to think that the State in its actual form can realise not only political equality, but also social equality.

This cleavage was born together with the political state during the French Revolution and it is still defining our society. This is the cleavage between the political and the social, between the general and the particular, and between true and real, and ideal and practice. In Marxist terms: the cleavage between citoyen and bourgeois.

This perception is not new, Marx has learned this antithetical thinking from Hegel, who explained the period of terror after the French Revolution as a consequence of the strong tension between the abstract revolutionary ideal and the specific content of the Revolution. But whereas Hegel speaks of a Weltgeist, that has to be alienated from itself to be able to progress, Marx is talking about the real, private human being. For him, it is not a matter of a dialectic of the spirit, but a human tragedy. For in the end it is not the State that creates the human Being, but the human being who creates the State. Political Emancipation has separated the true human being from the real human being. This real human being, the bourgeois, member of civil society, is just like the religious human being estranged from himself. He has outsourced the very best part of himself to the State, just like the religious person has outsourced his very best part to God. On this point, Marx is following Feuerbach, who said that by being religious, human beings are projecting the very best of themselves outside themselves. But just like with Hegel, Marx takes it a step further by not only looking at this as an individual procedure, but also as a social and political procedure, which doesn’t only occur regarding religion, but also regarding politics. Now we can see clearly Marx’criticism of political emancipation. In the extract, he says it like this:

Die politische Revolution löst das bürgerliche Leben in seine Bestandteile auf, ohne diese Bestandteile selbst zu revolutionieren und der Kritik zu unterwerfen.

In the end, the ideal of liberty and equality cannot be realised by an abstract State, in a political public domain; only the real people themselves can do this, by acting accordingly to their ideas and creating another practice. The overcoming of the cleavage within the human being, the victory over alienation: that is the real challenge for a movement for equal rights. Only then, human beings will be truly free. But, this cannot be done without having achieved political emancipation first. Historically spoken, the political emancipation accomplished by the French Revolution, was a necessary move.

Die politische Emanzipation ist allerdings ein großer Fortschritt, sie ist zwar nicht die letzte Form der menschlichen Emanzipation überhaupt, aber sie ist die letzte Form der menschlichen Emanzipation innerhalb der bisherigen Weltordnung. (p.356)

However, we should not mistake the political emancipation for a complete project of human liberty and equality. We are only halfway. To project needs to be finished before we can speak of real liberty and equality. The movement who will accomplish the project, thus Marx, will break up the actual world order and turn it upside down, because it will start to realise the abstract ideal of the political State within the real social and economic relations. Here, we already here the Marx of the Communist Manifest of five years later.

So, the final answer Marx give to the question of his colleague Bauer: how to get rid of religion, sounds like this: in the same way as we will get rid of the State and of the modern shape of human alienation. Marx replaces Bauers question by a new one, that is entirely different: how can we end human alienation and the inequality and injustice it brings?

To answer this, we have to look again at the relation between the criticism of Heaven and the criticism of Earth, but this time from another angle.

Extract 2: the religious character of the modern State.

This passage shows the conclusion of the debate between Marx and Bauer about the question whether or not political emancipation requires that Jews and other believers, have to renounce their religion. Bauer affirms this, Marx not.

For Marx, the relationship of the State with religion is the same as the relationship of the State with all particular elements in society, like property, family etcetera. The individual doesn’t have to renounce all these things, stronger: he or she is not able to do so. They only lose their political meaning. A State can already be a liberal State, without the member of its society being truly free. (p. 351-353).

As a consequence, people lead a double life: one as a political sovereign being – their ideal, let’s say heavenly existence. The other as a private citizen – their material, real, earthly existence. Marx says it like this in our excerpt:

Der politische Staat verhält sich ebenso spiritualistisch zur bürgerlichen Gesellschaft wie der Himmel zur Erde.

An important interjection: Marx makes a difference between Christian and religious. According to him, the Christian State of his time was in contradiction with itself. It was not really a State, because his relation to the particular elements in society was not really political, but theological. In the same time it was not really Christian. If the State wanted to realise Christianity, it would have had to abolish itself, like the New Testaments demands in some of its parts. (p. 359)

It must be clear that Marx analysis that the State has a religious character, doesn’t concern the Christian, incomplete State, but the complete, modern and secular, State. In a certain way, this State has partly a Christian character, because it represents a certain stage of human development in which Christianity is the ideal conscience. (p.360) The democratic State realises the dream and the presupposition of Christianity, the sovereignty of the human being. But it does this only in part, separated from the real human being. (361) Exactly on this point is the State religious. Just like religion, the State is “the recognition of man in a roundabout way” (Anerkennung des Menschen auf einem Umweg, p.353) It is because of this religious character of the modern State, that people cannot be asked or forced to renounce their religion. It would be unfair, because all members of the State are religious:

Religiös sind die Glieder des politischen Staats durch den Dualismus zwischen dem individuellen und dem Gattungsleben, zwischen dem Leben der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft und dem politischen Leben, religiös, indem der Mensch sich zu dem seiner wirklichen Individualität jenseitigen Staatsleben als seinem wahren Leben verhält, religiös, insofern die Religion hier der Geist der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft, der Ausdrück der Trennung und der Entfernung des Menschen vom Menschen ist. (p.360)

To Marx, religion is a deficiency, an abberation, since it is the product of the self-estrangement of the human being. People are not religious by nature. In its modern shape, religion is the consequence of the nature of the political State. This is how criticism of religion becomes criticism of the State. Criticism of Heaven is the condition for criticism of Earth.

The whole issue of the paradox between the bourgeois-citoyen is caused by the religious character of the State. The bourgeois can only recognize his true human nature except through the citoyen, by making a detour through the political State.

Marx has transformed the theological questions of Bruno Bauer into worldly, earthly questions by saying that religion has the same relation to the State as the rest of the civil society. The theological problem of Bauer – the conflict between the Christian State and Judaism has been turned into a political problem: the conflict between the democratic State and the civil society.

This works like this: as soon as the criticism of religion has unmasked the real condition of the human being, he has to understand that he doesn’t have any true reality, but that he is an illusory being.

Die Religion ist die phantastische Verwirklichung des menschlichen Wesens, weil das menschliche Wesen keine wahre Wirklichkeit besitzt. (Kritik der Hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie, p.378.)

In the modern world as it is now, religion has a right to exist, whether it is religion in ist Christian, Jewish, Islamic or Political form. The only way Religion can be suppressed, is by changing the social conditions from which it emanates.

Marx doesn’t believe in the liberal approach to religion, which puts religion politically and socially out of action by banishing it to private life. He does the exact opposite, by preserving the political aspirations of religion but taking them out of the religious sphere into the social struggle. Marx criticism of religion is immanent criticism. He raises the religious vision of a world without suffering, in which peace and justice will reign, to a social and political level, to be able to realise it for all humankind. In other words, Marx is concerned about human emancipation instead of political emancipation.

How he looks at the State is similar. He unmasks the State as religious. He shows the heavenly face of the Earth, as he has shown the earthly face of Heaven. The two criticisms are intertwined. The statement of Arend van Leeuwen I quoted before, has become more clear:

The criticism of Heaven is the condition of the criticism of Earth; The criticism of Earth is the fundament of the criticism of Heaven.

The ‘condition’ in the quote points to the false consciousness which gives the State a religious character. Marx is criticising Hegel here (through Bauer). Hegels Idea of the State as the Incarnation of the Absolute Spirit is, says Marx, in reality a mask behind which the real antithesis between bourgeois and citoyen is hidden.

The word ‘fundament’ points to this real antithesis, which Marx rejects as well. On the one hand he unmasks a false consciousness and on the other hand he shows a wrong reality. De alienation is both heavenly and earthly.

Marx opposes the false consciousness by criticising the State and by unmasking it as religious. Image and reality (superstructure and substructure as he will call them later) confirm each other. (Van Leeuwen p.159) The circle has been closed.

Conclusion

The ambitious assignment Karl Marx has given himself is to break the circle of heaven and earth by giving people a true reality. Criticism of religion cannot stop by shattering illusions, which people need to be able to bear their difficult life. Criticism therefore has to be follow by the changing of reality.

Criticising the political emancipation and the French Revolution means really to accomplish this Revolution by giving the abstract ideal a reality. But this reality asks for a new revolution, which will cancel out the French Revolution. The new Revolution is about reconciling the cleavage the French Revolution has created, the one between the bourgeois and the citoyen.

The bourgeois has to become more political, more idealistic you could say. He has to think more about the common good and less about his own interest. But this can only turned out well if the citoyen becomes more real, more social, by giving his ideals a practice and not only realising them on an abstract political level. It is not enough to change the political structures. The real conditions of our existence have to be changed. After all: who changes the earth, will also change heaven. And who criticizes heaven, also criticizes the earth.

This is how Karl Marx criticises the French Revolution, without dismissing her. He has shown that the European Enlightenment is everything but a finished project. It is a semi-finished product which leaves a lot to be desired. Especially modern Thinkers, adepts of the French Revolution like Karl Marx, knew about this.

Marx gives account of the historical situation in which the French Revolution took place, he analyses its limits and asks himself what is needed for the promises of the French Revolution to be redeemed. In this way he prevents that liberty, equality and fraternity become themselves abstract symbols without reality, in other words: religious concepts.

This attitude seems to be useful in the actual debate on religion and Islam. Who criticises religion with a plea of equality and liberty, should take the historical and political context of that religion into account and should also be aware of the limitations of the ideals of political emancipation. Those who manifest their support of Western Values as the answer to all kind of evil that strikes our world, should be careful not to defend abstract ideals as if those are the reality itself. By pretending that freedom and equality are not only ideals in our society, but completed accomplishments, find themselves guilty of a false reconciliation. Their criticism of religion consequently becomes religious.

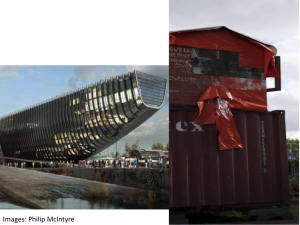

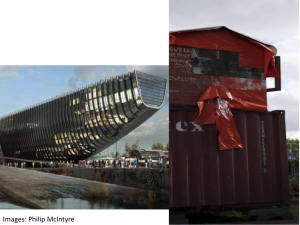

Which image does best represent the state of our European Values?

If we follow Marx, those Values do not appear as a shiny, but impenetrable monument, but more like a temporary shelter of some dwellers in time (the hut has a text of Heidegger written on it), who have to choose their position and their Values time after time.

Literature

Celikates, Robin, ‘Critique as Emancipatory Practice’, in: Karin de Boer, Ruth Sonderegger (eds.), Conceptions of Critique in Modern and Contemporary Philosophy, Palgrave McMillian 2011, 101-118.

Leeuwen, A,Th. van, ‘De hemel van de politieke staat’, in: A. Th. Van Leeuwen, Kritiek van hemel en aarde 2, Van Loghum Slaterus, Deventer 1972, 151-178.

Marx, Karl, Zur Judenfrage’, in : Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, Paris 1844. Marx Engels Werke Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1988 (MEW), band 1, p. 347-377.

Marx, Karl, ‘Zur Kritik der Hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie. Einleitung.’ In : Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, Paris 1844. MEW 1, p. 378-391.

English translations: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/jewish-question/

This is the text of a lecture at Queens University Belfast, July 2016.

Copyright: https://bureaudehelling.nl/critique-of-heaven-and-earth