The purpose of this chapter is to explore the philosophical and cultural dimensions of African management and African leadership. The specific intention is to provide a vision of what African management has come to mean in my own life, as a person, raised in the Zezuru tribe (in Zimbabwe), schooled in Zimbabwe and, having built a career in Southern Africa, as a writer and practitioner/consultant who has applied African principles to management. Rather than purporting to be a descriptive study surveying the field of African management, this chapter takes a more phenomenological approach and is offered as an example of how African management has been applied and promoted during the past 15 years of my career. My hope is that it is seen as an attempt to give readers a deeper understanding of the cultural world which has influenced my life and work, and that readers, both African and non-African, will be inspired to envisage what African management could be. In my own view, African management principles, as I have learned to apply them, have the capacity to mobilise collective business transformations in a unique and effective way. The chapter attempts to illustrate some of the reasons for the effectiveness I have witnessed in the application of African management strategies. Rather than purporting to provide empirical research for these methods, these are descriptions and personal accounts of what they are and why they work.

The purpose of this chapter is to explore the philosophical and cultural dimensions of African management and African leadership. The specific intention is to provide a vision of what African management has come to mean in my own life, as a person, raised in the Zezuru tribe (in Zimbabwe), schooled in Zimbabwe and, having built a career in Southern Africa, as a writer and practitioner/consultant who has applied African principles to management. Rather than purporting to be a descriptive study surveying the field of African management, this chapter takes a more phenomenological approach and is offered as an example of how African management has been applied and promoted during the past 15 years of my career. My hope is that it is seen as an attempt to give readers a deeper understanding of the cultural world which has influenced my life and work, and that readers, both African and non-African, will be inspired to envisage what African management could be. In my own view, African management principles, as I have learned to apply them, have the capacity to mobilise collective business transformations in a unique and effective way. The chapter attempts to illustrate some of the reasons for the effectiveness I have witnessed in the application of African management strategies. Rather than purporting to provide empirical research for these methods, these are descriptions and personal accounts of what they are and why they work.

African management

African management has origins similar to modern management, in that its roots lie in African oral history and indigenous African religion. In 1993, People Dynamics, a South African personnel management magazine, published two essays, in which I articulated the African philosophy of ubuntu as a basis of effective human resources.[i] In the same year, Ronnie Lessem, Peter Christie and myself co-authored one of the earliest texts on African Management in South Africa (Christie, Lessem and Mbigi 1994). The book included an article on the application and adaptation of indigenous African religious concepts and practices to organisational transformation at Eastern Highlands Tea Estates in Zimbabwe. In fact it was due to my positive experiences as CEO of this company, which inspired me to abandon my career as a business director and devote my life to the articulation of African and cultural values and philosophy in management.

At Eastern Highlands I had successfully applied a variety of African cultural and religious practices and concepts to the organisational challenge of transformation management. These included: the adaptation of traditional rituals and ceremonies used in African religion; encouraging group singing and dancing to build morale, enhance production processes and engage large groups in collective strategy formulation, and the use of myths and story telling to build leadership and organisational cohesion. With contributions from other writers at the time, such as Reuel Khoza, Peter Christie and Ronnie Lessem, African management as a field of study and practice began to flourish as a discipline in South Africa, from the early 1990s. The African philosophy of ubuntu and its emphasis on interdependence and consensus provided its foundation.

Compared with western management theory and practice, African management is characterised by flatter structures which stress inclusion, interdependence, democracy and broad stakeholder participation. Rather than formal, uniform policies, African managers call for an emphasis on flexibility in relation to policies, which can be easily initiated, changed and transformed through a broad-based collective, mass-scale consensus and participation of many stakeholders. Instead of the tendency towards impersonal relationships in western management theory[ii] within an organisational context, African culture calls for highly personalised relationships. In African organisations, harnessing spiritual and social capital is an important management challenge. While there is hierarchy in African organisations, respect for hierarchy is emphasised in ceremonies. What drives organisations, more than official roles within a hierarchy, is the informal power that derives from natural social clusters, and consultation and negotiation depend largely on who owns the issue. Representation of all stakeholders and inclusion of all groups are given emphasis, so that African management is more about allowing multiple leadership roles and greater flexibility. Finally African management tends to prefer a web of interdependence of roles, relationships and competencies and is less concerned with structure and function than western management.

Religious ritual and ceremonial foundations of African management

One of the core assumptions of my work as a practitioner and theorist of African management is the fundamental acknowledgement that, generally speaking, as Africans, we do not have a scientific western consciousness. Our African consciousness is deeply rooted in religion and spirituality in which symbolism and the expression of behavioural actions are more important than scientific logic. Rituals and ceremonies, symbols and mythology are all relevant and it is important to understand the link between these elements and African cosmology.

In African cosmology reality is deeply rooted in spirituality and spiritual interpretations of events, rather than in scientific interpretation of events. Therefore there is greater openness to what the spirits can do for you, or any communal organisation. In my own experience, such acknowledgement of spirituality is core to understanding African culture and African management. What tends to be in the minds of people I have worked with is how to harness spirituality. Questions that are asked are: how do you understand events spiritually? How do you petition the ancestors? How do you bond with those who have passed on? How and when do you give thanks? In essence, this is how the spiritual realm affects reality.

Mythology is an important part of the foundation of African management. Myths tell us who we are and our possibilities of becoming, as well as where we are. In fact, Joseph Campbell (Campbell and Moyers 1988) was right when he said: ‘What myths are for is to bring us into a level of consciousness that is spiritual’.

Indigenous religious rituals and ceremonies of transformation are an equally important aspect because they harness our emotional and psychic spiritual energy. These provoke contemplation and reflection to release us from the stultifying routines and common sense of daily life. They bring about the artful and joyful side of life. Their seductive beauty lies in the ugliness and uniqueness of their ceremonial regalia. It is important that rituals and ceremonies should be accompanied by rhythmic dancing and drumming, as well as singing which brings absorptive, as well as inspirational capacity. The sad reality is that without dance, music and singing, as well as bonding rituals and ceremonies in our life we suffer from high levels of self-alienation. Detailed below are some of the rituals and ceremonies of African Shona tribal religion that have been instructive in the design of transformation processes and practices I have adapted in southern Africa.

It is important to reiterate that the vision articulated in this chapter and the theoretical work offered, represents a view grounded in personal experience as a person born in the Zezuru tribe, which is one of the ethnic groups in the broader Shona tribe. While there are variations that exist in other Shona ethnic groups, such as the Karanga, and Manyika, the underlying cosmology is shared for the most part. In the interests of simplicity, I will generalise and use the term Shona, while acknowledging that there may be subtle differences among the ethnic groups just mentioned. This section will cover the following rituals, which I have begun to develop into a theoretical body of knowledge and to use as a basis for practical interventions.

– Corpse shadow theory / ritual;

– Crossroads theory / ritual;

– Dandaro renewal ceremony;

– Mukwerera Rainmaking Ceremony.

Corpse shadow cleansing ritual

In Shona tribal religion a dead body is not supposed to have a shadow, and a specific ritual, known as the corpse shadow cleansing ritual, is carried out when there is a shadow.[iii] A shadow indicates unfinished business on earth, which prevents the dead person’s transformation into the spiritual world beyond. A shadow also indicates that the person failed to have closure on a particular issue, such as bitterness over personal ill-treatment.

In order to deal with this transformation challenge, the family will have to consult a diviner for guidance and clarification. This is usually followed by a cleansing ritual. This enables the deceased person to proceed with the benefit of personal spiritual transformation into the world beyond.

Transformation leadership applications

This ritual, embodying a cleansing process, has been adapted for transformational purposes in the work place, as a way to express and uncover unresolved and unexpressed issues. The first step in transformation is to create inclusive platforms to deal with organisational grievances, fears, ghosts, tragic aspects of their collective history and pathologies. Examples of organisational issues which typically arise are: the tendency to blame and scorn others; negative feelings of helplessness and passivity; secrecy and denial; unexpressed collective historical grievances; unexpressed collective anger and bitterness; unexpressed collective fears and insecurities; collective alienation and isolation and finally avoidance and turf protection. The expression and healing of these negative spirits and feelings will enable the organisational community to free its collective energy and grapple with positive endeavours such as creating an inspiring image of its future. This has to be done within a flexible strategic agenda.

My experience is that it is very difficult to connect with the spirit of the organisation without the use of mythology, oral history and storytelling. It is not an intellectual journey but an emotional and spiritual journey. The use of collective dancing, music and singing is also imperative.

The cleansing process works in the following way. Organisations hold a three to five-day transformation ceremony around core strategic themes and key issues. These are called burning platforms, since they provide a context for people to give voice to burning issues. The agenda should be flexible and open to allow the expression of negative feelings, which opens the way to clear thinking. It is advisable to start with key role-players, some who are pro-change and some who are against change. It is important to lead the discussion in such a way that they articulate their change positions and agendas. Then, the facilitator makes the case for change and designs an inclusive process to manage the articulated change issues. Finally, it is important to formulate an inclusive process to craft a shared future vision, as well as a pathway to a shared desired future.

One client, the South African Post office, chose to use the burning platform process, at a point in time when they were experiencing a loss of R500 million a year. Racism was so rampant that the organisation was losing skilled managers, both white and black. There had been so many internal conflicts during one year (1998) that the human resources department had had to institute 4,200 different mediations. According to the human resources manager, most of these cases were racially motivated. In addition, people alleged that there was fraud in the organisation of R1 million rand. When we came to discuss the value drivers of the company, they said fraud around registered letters was a key one and had to do with the presence of syndicates. During the first days it was very difficult for whites coming to the workshops to share rooms with blacks, but after a number of workshops that was no longer an issue. As a result of the burning platforms and the building of group trust and group cohesion the Post office was eventually able to identify and then bust some of the syndicates that were involved. They couldn’t function properly as an organisation, until the burning platform processes were completed. They went on to make R750 Million a year. After a twoyear period, there was a great improvement in race relations. They eventually went onto commercialise some of their business units.

Cross-roads ritual

In a traditional context, this ritual is intended to help an individual and a group to deal with cross-roads issues in their life in order to leap into the unknown future. The purpose of the ritual is to help individuals and groups find a way to turn their backs on the unwanted present and past. The ritual is done at night in birth clothes at a four-way stop or cross-roads with the help of a diviner. The diviner will help the individual and relevant family group to articulate the issues that are faced, standing at the cross-roads.

The participants of the ritual face the four sides of the earth and utter incantations or mantras around their specific cross-roads challenges. They travel back home without looking back. They then eat red millet porridge mixed with cleansing herbs from the same bowl with clenched fists to signify their new fighting spirit. Every member in the extended family has to participate. This is known to harness the creativity of the group.

Transformation management applications

Anchoring strategic themes and burning issues should be the basis of designing learning materials for transformation workshops. The design of transformation workshops should be rooted in the cross-roads issues facing the organisation and the workshop participants, so as to facilitate emotional and spiritual connection. The facilitator must first deal with the negative issues from the past to enable the organisation and participants to harness the creative energy needed for forward movement. It is important for the facilitator to avoid becoming a hostage of the tragic element of someone’s history. Human beings have the capacity to overcome their limitations and reinvent their life and future. Heroes have demonstrated this capacity throughout history by turning disadvantages into advantages. In working with groups, do not blame the past; overcome its limitations and constraints. This is the essence of creativity. We cannot change our past. The past is our heritage. Our duty as such is not to condemn history; our duty is to change history. The goal is to create a sense of a shared destiny and a shared vision, as well as a shared performance agenda and shared bonding rituals to create shared meaning.

It helps the process to use a credible external facilitator, but leadership at every level of the organisation and community should own the change through high visibility at change ceremonies and rituals. Rituals and ceremonial leadership cannot be delegated, as the primary task of leadership is to create meaning and manage focused attention. The facilitator must foster an inspiring victory paradigm to overcome a victimhood paradigm that often leads to paralysis and inaction. He or she can use non-verbal communication. For example, it is possible to fight resistance to change with clenched fists. It is also important to create a collective fighting spirit of optimism. As leaders we cannot give what we do not have. We have to first create hope within ourselves to inspire us to peak performance.

Dandaro renewal ceremony

The ceremony is used for both renewal and remedial purposes. It is facilitated by an external diviner, and participation by a community of relatives and outsiders is essential. The Dandaro renewal ceremony focuses on the specific challenge faced by a particular extended family. It is a night-long affair, during which collective contemplation and reflection are mandatory. Although it is facilitated by a particular spirit of divination, all the spirits present are allowed to commune as soul mates and descend from the world beyond and assist in giving guidance to the family on the cross-roads challenges under consideration. This particular ceremony is always accompanied by collective singing and dancing, as well as drumming, and punctuated by the ululation of women to welcome spirits.

The singing of the ceremonial songs is always accompanied by spiritual wailing (kukaiva) to call the spirits for guidance, and punctuated by a special form of meaningless humming (mahonyera). In between the singing participants give their didactic message in conversational style.

Transformation management applications

At Eastern Highlands Tea Estates I re-enacted the Dandaro renewal ceremony as an inclusive education forum for organisational renewal to allow collective strategic reflection and dialogue involving everyone in the organisation. This was inspired by childhood religious experiences at the feet of the spirit cult of Dembetembe, the Rain Queen of the Vattera Clan of the Shona tribe. She had adopted me and appointed me as her personal assistant and prince at the age of three.

Organisational education should not just be an intellectual affair, but also a ceremonial and collective bonding affair, permitting joyful dancing, singing and drumming, so as to allow for feasting and the harnessing of the collective creative and spiritual genius of the organisation. It is difficult to develop and mobilize the emotional, social, creative, and spiritual intelligence of the organisation, which will dilute the impact of the transformation interventions of the organisation.

Mukwerera rainmaking ceremony

The Shona tribe of Zimbabwe has three major ceremonies. Ruvhuno is a ceremony that celebrates the ripening of crops. Rukoto is a ceremony which celebrates the harvesting of crops. The African American community has reinstituted this in the Diaspora in the form of Kwanza Celebrations.

The Mukwerera rainmaking ceremony (Lessem and Nussbaum 1996) is the most important strategic ceremony or forum that takes place before the rainy season, to allow collective strategic planning by the community. It is led by the Rain Queen or Rain King. It is an all-day affair which includes community education, mobilization and social bonding. Every family participates in its preparations and subsequently in the celebrations. Several bulls are slaughtered and eaten together with other food during the celebrations. For this ceremonial occasion, other lower level spirits are not allowed to participate, as the highest spirit, the Rainmaker Spirit, who is a representative of God on earth, is in charge. In the spiritual hierarchy this is very important and it is strictly enforced. Ceremonial collective singing, dancing and drumming is imperative, as well as collective bonding punctuated by ululation to express joy and gratitude to God and the spirits in the world beyond. During the celebrations the strategic challenges facing the community are hotly debated.

Transformation management applications

At Eastern Highlands Tea Estates I re-enacted the Mukwerera ceremony to democratize organisational strategy formulation, mobilization and effectuation. I called it the Production Festival and in Nampak I called it the World-class day, to capture the organisation’s aspiration to attain world-class manufacturing status.

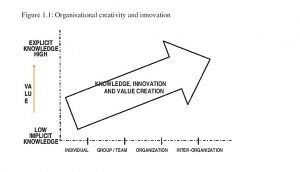

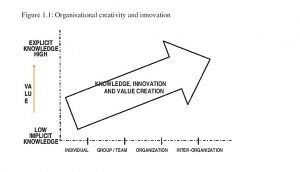

This strategic ceremony allowed both organisations to undertake effective strategic mobilization, renewal, reflection and implementation, as well as strategic education, so that employees could effectively become both strategic thinkers and doers. The organisations also succeeded in becoming time-based and team-based organisations, which accelerated value creation, as well as in becoming learning organisations, which in turn accelerated knowledge creation, sharing and application. The ceremony also inspired organisational creativity and innovation as illustrated in the diagram detailed below:

Figure 1.1: Organisational creativity and innovation

African indigenous knowledge creation and its relevance for management African indigenous knowledge systems and strategies for collective learning still have to be adapted and made universal so that they may become more relevant for management in other contexts. Their potential role in education, learning, knowledge creation and transformation has yet to be fully understood and articulated in the west.

African culture offers a very important element in transforming organisations and communities, because it requires the co-creation and integrated alignment of worldviews through shifting paradigms. Indigenous knowledge, ceremonies and learning processes provide inherent wisdom in this area.

African learning systems, however, focus on implicit rather than explicit knowledge and knowledge is uncodified rather than codified. The greater part of human knowledge is uncodified implicit knowledge that is difficult to access, transfer and learn. Uncodified implicit knowledge can only be accessed and learned through experience. Implicit knowledge, according to the Japanese thinker Ijiro Nonaka (Nonaka and Takuchei 1995), can only be transferred through practical experience based on relationships and trust between the learner and the mentor. This is where African indigenous knowledge creation has an excellent contribution to make. Most business knowledge is not codified and is also implicit. African collective and traditional educational methods have the potential to add value to business education, since they are so instructive in transferring uncodified implicit knowledge and in facilitating the rapid and collective learning of whole communities. African processes as highlighted in the rituals mentioned above, as well as collective learning systems to be discussed in these paragraphs shed light on practical experiences which are highly relevant in enhancing the collective learning. Collective learning requires both the social capital of trust and the intellectual capital acquired through reflective action. It is therefore important to draw inspiration from indigenous collective learning rituals and practices, such as African tribal initiation ceremonies, in our search for collective learning practices required to democratize knowledge and skills in modern organisations.The practices of the African collective learning systems are summarised in the following paragraphs.

The underlying philosophy stresses learning by doing, that is, reflective action learning. Learning is viewed and experienced as a collective effort; not just an individual effort, thereby embracing the fundamental philosophy of ubuntu. Another core component of collective learning in the African context is the principle ‘teach one and learn one’. In African culture, the best way to learn is to teach others so in this particular sense, the sharing of knowledge and skills is vital. Understood in a slightly different way, there is a strong belief that in order to get everything we must share everything. This is echoed by Professor Reg Revans (Revans 1983), who explains it more accurately, arguing that the people learn more from comrades in adversity than from experts on high.

In the context of African culture and knowledge creation, the social process of learning is as important as a learning curriculum or content in terms of programme design. We need to pay particular attention to social processes in terms of the bonding and learning rituals and ceremonies. In addition, collective learning requires us to celebrate and canonize our interdependence, which is the cornerstone of the ubuntu value system. In addition, there are several principles related to collective learning and knowledge creation. These include: the spirit of learning principle; the principle of personal destiny and the principle of learning through life skills.

The core notion of the spirit of learning principle captures the belief that the organisational spirit or climate establishes the unique horizons and perceptions of learning. The principle of personal destiny (dzinza in Shona) embodies the idea that learning is accelerated by a high sense of personal purpose, history and destiny as well as career pathing. Finally, the principle of learning through developing life skills means that learning is accelerated by being focused on survival challenges. In this sense, adaptive learning is vital. Again, this resonates with the writings of Reg Revans who states that collectives and groups that adapt to change effectively have a steep learning curve and that their rate of learning exceeds the rate of change facing them. These principles of collective learning derived from the traditional African wisdom and initiation rituals and ceremonies should guide multi-skilling and transformation efforts in our organisations.

New methods for managing transformation

The creation of a new system is a complex task, because of the fact that one is dealing with unknown elements. Although the known system has been discredited, the new system is unknown. This type of change is fundamental – it recognises the change of the whole system and not just a few elements in it. Political scientists call it transformation. Futurists call it a paradigm shift – a fundamental shift of our worldview is required. This is the type of change organisations are facing in the global economy today. It requires the development of new mass facilitation and mass mobilization methods. The current fascination in Human Resources Management with performance consulting does not deal with this kind of transformation. African peasant revolutions have developed advanced methods of managing transformation; mind shifting and changing of worldviews of a large number of communities. The only western social theorist and social activist who deals with this type of change management in the area of social action, is Saul Alinsky. He detailed this in his seminal work entitled ‘Rules of radicals’ (Alinsky 1972).

Having both participated in and witnessed the revolutionary struggles in both Zimbabwe and South Africa, I began to adapt the mobilization methods of nationalist and guerrilla movements, to the rapid massive transformation of business and state organisations. My experience is based on transforming a large packaging manufacturing organisation which employed 26,000 employees in South Africa. The entire project took three years to complete. This involved the transformation of racist organisational cultures into non-racial, non-sexist and high-performance cultures, as well as enabling the disadvantaged groups to reclaim public accountability, so as to rise to the challenge of nation building.

The second case where this model was applied was a large railway company that employed 66,000 employees. This transformation model was also implemented with remarkable positive results, by a large postal service and freight company employing over 25,000 people in South Africa.

Key elements of the transformation model

Underlying the practical applications of the transformation model is a number of key elements. The model focuses on the creation of a new reality or system and also has the potential to enable the co-creation of new paradigms, worldviews and mindsets. The model also focuses on the co-creation of a new memory of the future, shared values and a new shared agenda. Typically, mass mobilization of all employees occurs through mass workshops of 150-500 employees per session, around a new organisational strategic agenda and national vision. This is accompanied by the training and development of a large number of in-house transformation facilitators to run workshops. The training and development of a large number of transformation champions with line experience and responsibilities enhances the capacity of the organisation to implement transformation on a day-to-day basis in their work area. In addition, in the training strategy, efforts are made to ensure the inclusion of a large number of key role-players such as union shop stewards as transformation champions in their respective constituencies and structures. Although the external consultant facilitates 10-30 per cent of the workshops, the primary focus is on building a critical mass for transformation and in-house capacity to facilitate and manage change.

There are a number of additional requirements which serve to build the effectiveness of this transformation model. Every employee must participate in the transformation workshops and the workshops must be cross-functional, multi-racial, multi-level and large, to create high impact and give a sense of high connectivity. The content and process must be the same for every level and every group and must focus on burning issues facing the organisation. High velocity in implementing the transformation programme is key. The whole process must be completed within a maximum of one year, to avoid losing momentum. If the time is lengthened, the transformation process and programme can be deterred through the resignation of key role-players and the emergence of derailing events. Time is of essence. The politics of speed in managing transformation are important. Finally, managing the politics of transformation with key groups and role-players is a vital part of implementing the model successfully.

Programme content

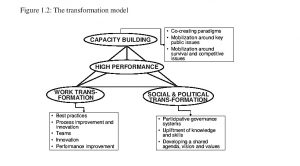

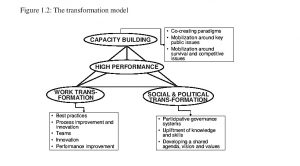

This model was also implemented with amazing success in a development corporation employing more than three thousand employees, and also in a medical service organisation employing more than one thousand employees. The transformation model focuses on developing and publishing high performance systems. At the heart of this transformation model is the need to achieve creative high performance and competitive alignment. The model has three key elements: capacity building, work transformation, and social and political transformation. Alignment of these three elements to translate into high performance is an essential ingredient for success. The model is detailed in the diagramme below:

Figure 1.2: The transformation model

The work transformation issues include fundamental change elements such as: the development and implementation of best practices through reliable and comprehensive benchmarking systems; the implementation of a process improvement and innovation system; and the design and development of teams. In addition, development of innovative products, practices and systems is enhanced by redefining the competitive rules. In addition, attention is given to the development and implementation of high performance management systems. This includes the management of work, product development and technology.

The social and political transformation issues include the following fundamental change elements: the development of participative governance systems in order to create a fair organisation and society; democratization of information, knowledge and skills so that every employee is both a strategic thinker and doer; the negotiation of a shared strategic performance agenda and finally the development of shared worldviews and a collective sense of shared destiny. Celebration of cultural diversity is an important aspect of the transformation model and this occurs by both valuing differences and identifying similarities.

There is also a deliberate investment in the capacity building of every employee, to develop their strategic capacity to understand work transformation issues, as well as social and political issues. In addition to this, there is a deliberate emphasis on developing global citizenship and a global perspective. The creation of critical awareness regarding the competitive nature of the global economy is vital; creating awareness in every employee with regard to economic aspects such as: how the global economy works, including the zero sum of its competition; how the national economy works, including the challenges of nation building, as well as the development of a national competitive agenda. The intention is to help ordinary employees to reclaim public accountability and to become development cadres so that they fully understand how their company works and how the industry functions.

The purpose is to create the capacity in employees to understand the survival and competitive challenges at five levels: global, national, industry, company, and personal. The intention of these learning strategies is to shift employee mindsets around governance and public accountability through participative co-creation of new paradigms.

Detailed below is an example of the course content for a three to five day workshop for South African companies:

– The challenge of economic liberation;

– Managing our heritage and the past;

– Management of diversity and affirmative action;

– Management of trust and diversity celebration;

– The challenge of managing organisational and personal transformation;

– SA transitional and transformation challenges;

– Strategic market and performance agenda;

– Building a corporate vision community.

Managing the heritage of the past, present and the future

I have applied transformation management in the South African Post Office (SAPO) to deal with strategic diversity and transformation issues as well as performance issues.

Both were necessary for the Post Office to become economically viable. These collective learning forums were named after selected strategic and transformation themes. They were called Strategic Diversity and Transformation programmes (SDT). The collective learning forums involved 26,000 employees hotly debating the strategic postures and transformation challenges facing the organisation. Each forum was residential and lasted three days.

The focus of the organisational learning process was on breaking even and attaining economic viability two years ahead of the schedule. The process was implemented with my help and an army of trained in-house transformation champions and facilitators, 95 in number. Through collective learning processes the issues were resolved. The same organisation was also interested in managing the difficult aspects of the past. The purpose of this module was to create extreme discomfort with the past in white participants so that they could let go and begin to search for an attractive memory of the future. A few well-selected historical facts would be woven into a tragic historical epic in a very humorous way, to produce disgust with the past and the resolution to create a new future among the participants.

The presenter would take many selected historical facts and weave them into tragic stories and this module was normally presented at the end of day one of the workshop. It used to leave the white participants in a complete state of painful disgust of their past and black participants very angry about their past. Therefore, discomfort was created in both groups and they would go to sleep in a tormented state, ready to travel into the future the next day.

Survival strategies for minority and majority groups in South Africa

The next morning the presenter would help the white SAPO participants to craft a survival strategy to thrive and prosper in a hostile political environment without political power. The presenter would draw examples from minority groups who prospered and succeeded in hostile environments without political power, such as the Jews. The elements of the survival strategies of minority groups must develop into a partnership with the majority and the development of a new patriotic agenda that includes the majority group. From the perspective of the majority group, they have to rise to the challenge of nation building. The majority group needs to shift from a victim-hood mentality to a victor-hood mentality. The majority cannot be both victims and victors. There is a need to make the shift, moving to a decisive resolve and focus on governing the country efficiently and fairly. This requires hard work. This gives the majority group a new positive agenda and vision.

The second day would end with a bonding ceremony around a big outdoor fire. People would share food and drinks. This is punctuated by collective singing and dancing to create the social capital required to chart and travel the difficult and trying road of organisational transformation.

Spirits of African management

Management is not a science but more like an art where knowledge is eclectic with a bias towards religious mythology and oral history, as well as philosophy. Mythology, as mentioned previously, is important in a strategic transformation process Myths serve four functions: A mystical, cosmological, sociological and pedagogical function. The mystical function deals with the mystery of our existence and that of the universe. We always address the transcendent mystery through the actual conditions in the world. The cosmological function shows the shape of the universe, which is the essence of science and highlights how human beings understand the universe. The sociological function supports and validates a certain social order. This accounts for the variation of myth from place to place. The pedagogical function of myth shows us how to live human life under any circumstances. Biblical parables serve as good examples in this regard. For example, Lazarus, the talented ten, and the prodigal son, the latter being about forgiveness and reconciliation particularly in family matters.

In African culture, myths are stories about our collective historical experience, shared destiny and heritage as well as about shared personal destiny (dzinza). These myths have been built around the stories and are integrated with well selected historical facts. The writer uses this technique extensively on the training modules for a variety of topics. They have also been captured live on video for the purpose of training facilitators, change agents and development practitioners.

This technique, which I now call mythography, is a very powerful instructional tool for creating new learning paradigms and for building a sense of hope and shared destiny. Mythography is also very effective in managing the spiritual, emotional and social resources of the organisation. It is one of only two techniques that have the potential to manage spiritual resources and raise spiritual awareness. Jesus of Nazareth used a similar instructional methodology, particularly the extensive use of fables and myths called parables. Essentially, Mythography = History + Mythology.

Organisations need role models who are mythical heroes to personify and affirm their purpose, meaning and values, particularly in times of rapid change. Mythic heroes give people something to strive for in order to attain both organisational and personal transformation. Mythic heroes also help people to address the contradictions of human life and the mysteries of human existence. This is what the story of Job accomplished in Jewish and Christian cultures. It poses the question: ‘Why do bad things happen to good people?’ Joseph Campbell aptly comments in this regard, saying: ‘When a person becomes a model for other people’s lives, he has moved into the sphere of being mythologized’.

A good example of this is the role Mandela played during the Southern African struggle as a mythic hero. Although he was in prison, he inspired thousands of political activists and freedom fighters. The late Herbert Chitepo played a similar role in the Zimbabwean struggle, although he had been assassinated. This is the role Edward Mondlane, the founder of Frelimo, played in the struggle for the liberation of Mozambique, although he had been assassinated very early in the struggle by hired hands of imperialists. Amilcar Cabral played a similar role in the struggle for liberation in Guinea Bissau, although he, too, had been assassinated by imperialists during the early part of that struggle. Mbuya Nehada, the female revolutionary leader of the first Chimurenga (‘revolution’) in Zimbabwe, played a similar heroic role in that country’s liberation war.

Facilitators and development practitioners can create mythic heroes in communities and organisations to inspire development as well as transformation efforts. This can be done in the following manner detailed below. Firstly, select an individual who is prochange and has done amazing things regarding transformation. Then create a heroic story around this particular individual. It is important to increase his / her visibility in the community or organisation; in this way it becomes possible to reposition the heroic individual in the community or organisation. This intervention not only helps to brand the hero/heroine but helps to create space and a forum for him/her. It also encourages and inspires him/her to achieve in the chosen field. The new result is a mythic hero who personifies the new vision in the values of the organisation. Finally, it is crucial to constantly tell the story, which then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy for the chosen individual. Ultimately, the individual has to find an aspect of myth that relates to his/her own life. Organisations need role models, mythical heroes to personify and affirm their purpose, meaning and values.

In the writer’s own transformation projects with the Agricultural Rural Development Corporation (ARDC), Spoornet, Nampak, Development Bank of South Africa (DBSA) and the South African Post Office (SAPO) he endeavoured to mentor and create mythic heroes who would then inspire the transformation efforts.

Religious, philosophical foundations of African management

In addition to understanding the role of myth in transformation, the following sections seek to elaborate on the spiritual and philosophical elements of African culture, which underpin African management.

African spiritual perspective

The African spiritual life is pervasive and deeply rooted in every area of life. There is no separation of religion from any other areas of life and religion is fully integrated with life in a remarkable rhythm. For this reason, social capital – which embodies an organisation’s emotional and spiritual resources – is a distinctive competitive factor akin to intellectual capital. Social capital affects the impact of any strategic intervention and the ultimate effectiveness of policies, procedures and processes. But modern management thinking practices and literature are generally weak in managing emotional and spiritual resources, which also help determine the value of an organisation, although there are some authors who are beginning to focus on this area.[iv]

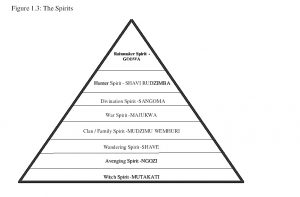

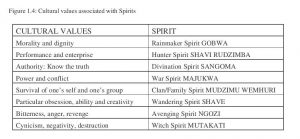

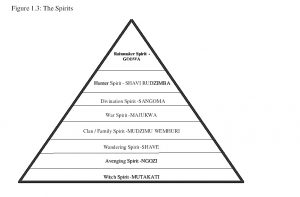

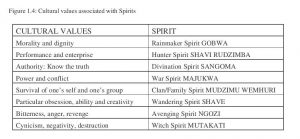

Science is not instructive on how to manage social capital in organisations. Social capital is a different form of energy and level of consciousness and requires a different knowledge base. Understanding about the role of spirits, articulated in traditional African religions can contribute to social capital management and its transformation. I have developed, for example, the hierarchy of African spirits, which is transtribal, as a model for managing cultural, emotional, and spiritual resources in an organisation.

In African spirit religion, the spirit represents our ultimate real self, our inner self and total being, and our total consciousness. The spirit is who we really are. In terms of management, the spirit is the ultimate energy and consciousness of an organisation. The spirit carries an organisation’s values and essence. The African spirit model serves as a metaphor to capture an organisation’s prevailing climate, culture, energy and consciousness. This model can be used as a tool for auditing the dominant spirits and cultural values of an organisation in a live, collective and a participative manner.

The model can also be used as a framework for managing and transforming an organisation’s social capital – its emotional and spiritual resources. It can, potentially, be more effective than sophisticated cultural surveys and psychological techniques, which some employees might not understand because they lack basic literacy skills. The presence of illiteracy is a factor that can skew the result of traditional western surveys.

The model has been used as a diagnostic tool to transform and create social capital in large business and state organisations in South Africa, such as the South African Post Office, Spoornet – SA National Railway, and the Agricultural Rural Development Corporation.

The spirits of management

There are many ways to extract the myths and to discern the spirits of an organisation. You can ask participants to share their most memorable experiences, or ask them to share stories of the most remarkable characters in the organisation. If the stories are negative, it means that the myths and spirits of the organisation are negative. The following descriptions of spirits in the hierarchy may be useful to some readers to help diagnose positive and negative spiritual dimensions within organisations. They are described in the Shona language, but I have found that they have broader relevance.

The destructive spirit

The Witch Spirit Mutakati is the lowest spirit in the hierarchy of African spirits. This is an evil spirit that wants to spoil everything in life and on Earth. In terms of the corporate collective spirit, it is characterized by destructive cynicism, negative thinking, and passive and active sabotage. This spirit devours an organisation’s energy. It is a dominant spirit in sluggish businesses and government bureaucracies.

The powerless spirit

The Avenging Spirit Ngozi is usually good but has been treated unjustly. As a result, it harbours anger, bitterness, and revenge. It is the dominant spirit among marginalized and powerless groups in society and organisations. This is the predominant spirit in dispossessed groups and the underclass of any society and organisation. Unless such groups can overcome their bitterness and anger, they will not be able to negotiate a new reality and new vision for themselves or their organisations. They can also become a danger to themselves and society as a whole.

Figure 1.3: The Spirits

The innovative spirit

The Wandering Spirit Shave is the spirit of an outsider who comes to the family or clan as a White Knight on a specific area or issue. This is an unusual individual who has a particular obsession and unique creative ability. It is the spirit of innovation. This is a weak spirit in many modern organisations in which innovators are not accepted or rewarded but, at best, just tolerated. The key strategic lesson is that innovative ideas may have to come from outside the organisation or from outsiders to the accepted corporate system. That suggests a strong case for employment practices that can attract mavericks, who usually have incomplete or unusual résumés. Organisations may also have to make use of reputable consultants to generate creative ideas. The insiders may be too close to their systems to envision potential realities. It is difficult to challenge a corporate culture from within, as it is career-limiting. The second strategic lesson is that innovation may have to be managed outside of the formal structure, giving rise to the need to create parallel structures for innovation.

The family spirit

The Clan Spirit Mudzimu Wemhuri is a family spirit that is interested in the survival of its group. This spirit enhances group solidarity through specified rituals, activities, ceremonies and symbols. It is important for building team-based, world-class organisations. It also serves to emphasize the importance of rituals, ceremonies and symbols in designing organisational teams.

Figure 1.4: Cultural values associated with Spirits

The personal spirit

The War Spirit Majukwa is a spirit of personal power, conflict and gamesmanship. It helps us understand power cultures and how to create power and influence in organisations. The rise of spider-web structures in modern organisations makes it imperative for individuals to develop power skills for personal influence in order to accomplish objectives.

The spirit of truth

The Spirit of Divination Sangoma knows the whole truth, which is his truth, and is not open to other views. Experts and specialists in organisations typically personify this spirit, as do most traditionalists. The spirit reduces the rate of learning in an organisation and its ability to adapt to change. Therefore we should populate action learning teams with non-experts and mavericks.

The restless spirit

The Hunter Spirit Shavi Rudzimba is a restless spirit and is the spirit of entrepreneurship. It has an eye for opportunity and deal-making. This spirit has a marked quest for pragmatic, creative solutions to survival and competitive challenges. The rituals and ceremonies surrounding this spirit help us develop practices to manage entrepreneurship in organisations.

The relationship spirit

The Rainmaker Spirit Gobwa is concerned about our relationship with the organisation and other people, as well as with our ecological, social, political, economic, and spiritual environments. This spirit takes care of our whole universe and is concerned with truth, morality, balance, and human dignity. This spirit helps clarify the stewardship role of the CEO and the need to take accountability for the whole organisation, as well as being its conscience. The primary role of a CEO is to look after the spirit of the organisation and its total social capital.

Strategic lessons from the Spirit Hierarchy model

In any given situation, there will be two or more dominant spirits that determine the social capital of an organisation. The dominant spirits determine the organisation’s outcomes, consciousness, culture and energy levels.

The African Spirit Hierarchy model can be used to audit the dominant culture and values, as well as the organisational climate in a collective, participative manner through dialogues and bonding rituals that allow group psychological departure and rebirth. The ceremonies and symbols that are integrated into the process provide access to the collective unconsciousness of the organisation. The whole process is enhanced by one or more elements of storytelling, singing, dancing and mythography.

It is important to dispel negative spirits for a positive organisational climate to flourish and make renewal efforts sustainable and high-impact. Organisations cannot let go of a negative past and embark on the critical path of corporate renewal as long as there are deadening, routine activities and processes. There is a need to design rituals and ceremonies of departure and rebirth. As a general rule, competent and charismatic outside consultants must facilitate those. Organisations cannot embark on a cultural renaissance without dealing with past grievances.

Organisations have to know where they are coming from to find out where they can go. They have to know who they are before they can know what they can become. Strategic visioning and values exercises have failed because of their lack of a ‘spiritual dimension’, for want of a better term. Such exercises have ended up with empty slogans that are neither practiced nor taken seriously. Organisational transformation is not just an intellectual journey; it is also an emotional and spiritual journey. In order to access the emotional and spiritual resources of an organisation, appropriate bonding symbols, myths, ceremonies, and rituals are needed.

Cultural and philosophical foundations: A comparative analysis

Cultural philosophy is vital in leadership because it enables managers to understand philosophy and contextual realities. This is what ubuntu; the philosophy of African management can contribute to the management discipline. Ubuntu means ‘I am because we are; I can only be a person through others’. It is only in the encounter of others in our relationships that we discover who we are. This requires trust in others and a canonization of the values of interdependence, respect, consensus, solidarity and human dignity, as a basis of management practices. Management excellence requires us to celebrate the richness and diversity of global cultures.

We are all products of our culture. We can only see what our cultural paradigms allow us to see. Therefore, all managers and employees only see what their cultural paradigms in their organisations allow them to see. The clay material of management is subjectivity. Management is emotional, social, spiritual, political and rational.

Therefore, any approach to the study of management should reflect this complexity and diversity. The current Cartesian scientific paradigm may be necessary but not sufficient in understanding management – it only addresses the rational element of management. Ultimately, the challenge of management is to move from being a science of manipulation, to also being a science of understanding. The discipline of management is culturally biased because it is about the issues of how we organise people and how we manage the work they do. Hence, the management discipline should encompass the great theory of being.

It is important to explore the role of cultural paradigms in organisational leadership. We are all products of our cultures. Charles Hampden-Turner and Alfons Trompenaars (1993) argue in their book ‘The seven cultures of capitalism’ that we can only see what our cultural paradigms allow us to see. Therefore, all leaders and employees can only see what their cultural lenses allow them to see in organisations. This has serious implications for leadership theories and practices. The national host culture determines how the challenge of leadership in organisations is approached. Thomas H. Kuhn (1996), in his book ‘The structure of scientific revolutions’, defines a paradigm as follows:

… accepted examples of actual scientific practice, examples which include law, theory,application, and instrumentation together – [that] provide models from which spring particular coherent traditions of scientific research. Men whose research is based on shared paradigms are committed to the same rules and standards for scientific practice.

His observation of creative thought leaders in the scientific fields was that people who understood the prevailing scientific paradigm in their field and had the courage to think and explore the frontiers beyond it. Organisational leaders should not only be able to understand the culture of the host country in which their organisation is operating, but must also have the personal courage to think outside it. At the risk of over-simplifying and over generalizing, the influence of the four cultures of the four corners of the globe will be examined. It is important to note that every culture has its competencies, strengths and weaknesses. The essence of leadership excellence is the ability to leverage the host African culture and then harness complimentary competencies of the distinct global cultures of the four corners of the globe.

Overview of the global cultural diversity for leadership excellence

Let us start by examining the cultural worldview of the European North and its strategic implications for leadership, theory and practice. The cultural worldview of the North is ‘I am because I think I am’. There is an emphasis on rational and scientific thinking. European leaders have harnessed this competency in planning, as well as scientific and technical innovation. In fact, the stunning achievements of European leadership and civilization have been due to scientific and technological innovations, as well as rational planning techniques. Between 1500 and 1700 there was a dramatic shift in the way people pictured the world and in the whole way of thinking in Europe. The new scientific mentality and the new perception of the cosmos gave our European civilization the features that are characteristic of the modern era. They became the basis of the paradigm that has dominated European culture for the past three hundred years, according to Capra (Capra 1982). René Descartes is usually regarded as the founder of the modern scientific paradigm. The belief in the certainty of scientific knowledge lies at the very basis of the Cartesian philosophy and of the worldview derived from it. The Cartesian belief in scientific truth is reflected in the scientism that has become typical of the Western culture. Thus, Descartes arrived at his most celebrated statement Cogito, ergo sum – ‘I think therefore I exist’. The European cultural paradigm can assist leaders to plan and create a memory of the future.

Eastern Asian cultural paradigm

The eastern Asian cultural paradigm is characterized by an emphasis on continuous improvement to attain perfection. In fact, most Asian religions emphasize a pilgrimage into inner perfection. From these religions techniques of personal development and perfection have developed, such as yoga from Hinduism and meditation form Buddhism. The Eastern worldview can be summarized as ‘I am because I improve’. According to the Japanese leadership expert Masaaki Imai (Imai 1986):

If you learn only one word of Japanese make it Kaizen. Kaizen strategy is the single most important concept in Japanese management – the key to Japanese competitive success. Kaizen means improvement. Kaizen means ongoing improvement involving everyone: top management, managers and workers.

It means much more than that. It means a philosophy that encourages every person in an industry – every day – to make suggestions for improving everything; themselves, their job, their workplace, their factory layout, their telephone answering habits, their products and their services. The giant Japanese electronic company Matsushita receives some 6.5 million ideas from its employees every year. The cultural business strategy of kaizen inspired the successful Japanese economic revolution because this cultural competency allowed the Japanese to manage mature manufacturing technologies through innovation and team structures such as quality circles. This gave birth to a worldwide revolution in quality through the participatory leadership best practices of Total Quality Management (TQM) and Total Productive Maintenance (TPM).

Western cultural worldview

America is a young successful dominant civilization which exemplifies a western cultural worldview. Since it is an adolescent civilization, it believes in what Robert Reich (Reich 1991) has called the myth of the individual hero. The Western worldview puts emphasis on the individual lone hero who, through his individual nobility, independence, courage and conviction, saves organisations and communities from their fate. This cultural worldview can be stated as: ‘I am because I, the individual hero, dream and do’. More specifically, this cultural paradigm translates into: ‘Concentrate on your self-interest and you will automatically serve your customer and society better, which in turn will let you serve your self-interest’. The classic representative theorist of the Western paradigm is Adam Smith, whose main thesis is that collective social goals are a by-product of self-interest. Therefore, if each individual pursues their own selfish personal interest, an invisible will automatically serve the common interests of the larger society. Adam Smith published a book entitled ‘The wealth of nations’, which became a manifesto of American enterprise. Adam Smith summarized the heart and soul of the Western American cultural paradigm as follows:

[This individual] … intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it … (Smith 1937: 423).

Another feature of this paradigm is the guts to dream and the personal courage to put them into action. This cultural paradigm has a visionary enterprising trait which has inspired American economic development and created the largest and most competitive economy in human history. It takes substantial courage and a capacity to dream big to think of inhibiting other planets in the manner Americans have done and demonstrated.

African cultural paradigm of the South

The African worldview is characterized by a deliberate emphasis on people and their dignity – the emphasis on the collective brotherhood of mankind called ubuntu, which is the African perspective of collective personhood derived from muntu or munhu. Ubuntu literally translated means ‘I am because we are; I can only be a person through others’. There is deliberate emphasis on solidarity and interdependence which is a key characteristic of African communities of affinity. The Archbishop Desmond Tutu puts it more clearly:

Africans have a thing called UBUNTU; it is about the essence of being human, it is part of the gift that Africa is going to give to the world. It embraces hospitality, caring about others, being willing to go that extra mile for the sake of another. We believe that a person is a person through other persons; that my humanity is caught up and bound up in yours. When I dehumanize you, I inexorably dehumanize myself. The solitary human being is a contradiction in terms, and therefore you seek to work for the common good because your humanity comes into its own in community, in belonging.

The key values of African leadership include five key dimensions. Firstly, respect for the dignity of others. Secondly, there is a focus on group solidarity: an injury to one is an injury to all. Thiedly, teamwork is deeply valued, meaning that none of us is greater than all of us. Fourthly, service to others in the spirit of harmony is a driving value. Finally, there is a profound value accorded to interdependence: Each one of us needs all of us. Charles Handy, the British guru on management echoes the same sentiments on collective personhood when he writes:

We have to find a personal security in our relationship too. We are not meant to stand alone. We need a sense of connection. We have to feel that it matters to other people that we are there. Because if it makes no difference whether you are there or not then you really begin to feel like a meaningless person. If you have no connection to anybody, you have no responsibility and therefore no purpose (in Gibson 1997).

African cultures stand Adam Smith’s premise on its head. In terms of the African cultural paradigm, the needs of the group or community are considered first, and then the invisible hand will automatically take care of the desires of the individual. Serve your society and stakeholders to the best of your ability and you will automatically achieve your own personal goals, which will allow you to align them with the needs of your relevant stakeholders, including customers. It therefore follows that the African leadership paradigm has a bias towards servant leadership. The practices of the African paradigm of leadership are best articulated by Robert Greenleaf (Greenleaf 1996). These best practices are:

Listening: The servant leader seeks to identify and clarify the will of the group. They seek to listen respectfully to what is being said. Listening also encompasses: getting in touch with one’s inner voice; seeking to understand what one’s body, spirit and mind are communicating. Finally, listening with regular periods of reflection is essential to the growth of the servant leader.

Empathy: The servant leader strives to understand and empathize with others. People need to be accepted and recognised for their special and unique spirit. The most successful servant leaders are those who have become skilled empathetic leaders.

Persuasion: Persuasion is the clearest distinction between the conventional authoritarian leadership style and that of servant leadership. The servant leader is effective at building consensus within groups. The emphasis on persuasion rather than consensus is the heart and soul of African leadership because it is embedded in the ancient African philosophy of ubuntu. According to Nelson Mandela:

Then our people lived peacefully, under the democratic rule of their kings … Then the country was ours in name and right … All men were free and equal, this was the foundation of government. The council of elders was so completely democratic that all members of the tribe could participate in its deliberations. Chief and subject, warrior and medicine man, all took part and endeavoured to influence decisions (Mandela, speech from the dock, at his 1962 trial).

According to George Ayittey (1999), African societies have, for centuries, enjoyed a tradition of participatory democracy. The organisational structure of indigenous African systems was generally based on kinship and ancestry. Survival of the tribe was the primary objective. Each ethnic group had its own system of government. These were unwritten constitutions like the constitution of Britain. Customs and traditions established the governance procedures. All African political governance systems in both chiefdoms and kingdoms started at village level comprised of extended families and lineages. Each village had its head chosen according to established rules with checks and balances. The chief was assisted by a small group of confidential advisors drawn from close friends and relatives called the inner council. If he disagreed with them, he would take the issue to the council of elders, a much wider and more formal structure consisting of hereditary headmen of lineages or wards. Their main function was not only to advise the chief but also to prevent the abuse of power by voicing its dissatisfaction and by criticizing the chief. The chief would inform the council of the subject matter to be dealt with. The matter would be debated until a decision was reached by consensus. The chief would remain silent and listen as the councillors debated the issues. He would weigh all viewpoints to avoid imposing his view on the council. The chief did not impose his rule – he only led and assessed the collective opinions of the council.

The people were the ultimate judge on disputed issues. If the council failed to reach consensus, the issue would be taken to the assembly for debate by the people. Every person was free to speak and ask questions. Deliberations continued until consensus was reached. Minority positions were heard and taken into account. In a majority rule process minority positions are ignored. The hallmark of African leadership traditions and practices is consensus democracy in order to accommodate minority positions to ensure the greatest possible level of justice and avoid sabotage during the implementation process. Compromise, persuasion, discussion and accommodation, listening and freedom of speech are the key elements of the African leadership paradigm. Consensus is difficult to reach on many issues. African political, social and economic leadership tradition is noted for the length of time required to reach consensus and it may take weeks to attain unity of purpose.

Consensus, by its very nature, is the antithesis of autocracy. The problem with the Western cultural leadership paradigm with its emphasis on individualism is that it scorns its own origins in the supportive community. The dauntless entrepreneur is a self-made man. According to Trompenaars et al. (1993): ‘This may be a good political argument for keeping the money you have accumulated, but it is a very dubious claim in reality, and one that sells short the many who sustained you’. The view of the African paradigm is that the nurturant community is the cradle of the individual. Therefore it follows that many changes could be made to transform organisations by shaping them as enterprising communities that could increase rather than decrease the individuality if each member. To focus on individuals only is to miss out on all the social and collective arrangements which can be altered to enhance the contribution of the individuals. In African cultures team rewards take precedence over individual rewards; the team is likely to support and reward with their friendship and respect the higher performers and the innovative individuals within the group. If the bonus is paid to individual high performers or individuals identified as more creative, the group is more likely to gang up on those whom they think are most favoured by management, sabotage their performance and socially punish them for their creativity. Star individual performers will benefit substantially from team rewards as opposed to individual rewards.

Healing

Many people have broken spirits and have suffered emotional hurts. Servant leaders should recognise that they have an opportunity to ‘help make whole’ those with whom they interact. According to Robert Greenleaf (Greenleaf 1996):

The servant as a leader – there is something subtle communicated to one who is being served and led if, implicit in the compact between the servant leader and the led, is the understanding that the search for wholeness is something they share.

Perhaps former President Nelson Mandela can be described as an epitome of African leadership virtues, particularly in terms of healing, compromise and diversity tolerance, as well as his focus on creating racial harmony and consensus democracy. Nelson Mandela says:

I am prepared to stand for the truth, even if you all stand against me … I am writing my own personal testament; because now that I am nearer to the end, I want to sleep for eternity with a broad smile on my face knowing that, especially the youth, can stretch out across the colour line, shake hands and seek peaceful solutions to the problems of the Country.

He went on to comment on the destiny of whites in South Africa:

Young Afrikaners had a specific and central contribution to make to the development of the South African nation and had too much potential to allow themselves to be marginalized.

Mandela also said that he had always fought against the domination of the majority by the minority, as well as the domination of the minority by the majority. This is the essence of African consensus democracy which seeks to accommodate minority groups.

Servant leaders seek to nurture their abilities to ‘dream great dreams’. The ability to look at a problem from a conceptualising perspective means that one must think beyond day-to-day realities. Servant leaders are called upon to seek a delicate balance between conceptual thinking and a day-to-day focused approach. In other words, in terms of the African leadership paradigm, one of the key functions of leadership is the ability to manage meaning by creating the memory of an attractive future. Leadership has to have the ability to create a shared agenda and vision that is capable of transforming the status quo, as well as the rare ability of enrolling people into the vision and galvanizing support for it. The leaders have to be able to energize people to overcome major obstacles towards achieving the vision of transformation by managing attention to achieve focused excellence. They have the ability to capture their vision in captivating language. Mandela can serve to illustrate this dimension of African leadership practice:

We have triumphed in the effort to implant hope in the breasts of millions of our people. We enter into the covenant that we shall build the society in which all South Africans, both Black and White, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their inalienable right to human dignity; a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.

Self-discipline

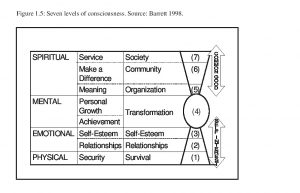

Yet another key element is that African leadership practices cherish a warrior tradition. African chiefs and kings were expected to lead their people in terms of war. Management of self-discipline is very important; doing very ordinary things in an extraordinary manner, as well as walking the talk, thus putting their sincerity on constant display in order to create trust. Management of social capital by creating trust is a key element of African servant leadership

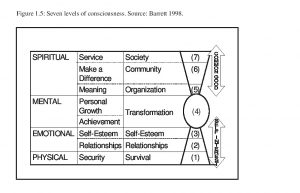

Figure 1.5: Seven levels of consciousness. Source: Barrett 1998.

Consciousness

In terms of the African leadership paradigm, leaders have to be sharply awake. They have an inner serenity. They have a high degree of personal consciousness. High consciousness can only be attained through a personal spiritual journey, by reaching into the depths of our spiritual inner resources to transcend our self-interest and attain a high level of personal transformation to be able to focus on the common good in service of society and the enterprising organisational ability. This also enables leaders to overcome the limitations of their historical circumstances inspired by a sense of personal destiny, which enables them to infuse spiritual energy into the organisation. For this to happen, leaders have to have a sense of connection with both the past and the future. They need a sense of legacy inspired by being rooted in their culture and traditions. In the African worldview, leaders are the custodians of culture and a particular civilization. They have to have a highly developed sense of personal destiny (dzinza) by knowing who they are, to become what they know they can become, by knowing their personal and family history, as well as tribal and national history to serve as a compass and a reference point in order to find their paths in a changing world.

Conclusion

The genius of European (North) leadership tradition lies in planning and technical innovation. The genius of the American (West) leadership tradition lies in entrepreneurship and a bias for action. The genius of Asian (East) leadership tradition lies in process innovation to attain quality and perfection. The genius of African (South) leadership tradition lies in ubuntu – interdependence of humanity by emphasizing human dignity and respect through consensus democracy and people mobilization, solidarity and care. Therefore, Richard Pascale (Pascale 1990) was right in saying:

Leadership reality is not absolute; rather, it is socially and culturally determined. Across all cultures, in all cultures and in all societies, human beings are coming together to perform certain collective acts, encounter common problems which have to do with establishing direction, co-ordination and motivation. Culture affects the way in which they can be resolved. Social learning also establishes horizons of perception.

NOTES

i. These essays were awarded a prize by the Institute of Personnel Management (IPM) for their originality.

ii. Some of the writers who have articulated classical management theory in Europe and America are Peter Drucker (2005) and Kurt Lewin (1973).

iii. In my own experience, the corpse shadow ritual is commonly found in all Nguni groups in South Africa.

iv. Some examples: Patricia Auberdine (Megatrends 2010) writes eloquently on the emergence and importance of spirituality and spiritual capital in organisations; Verna Allee (2003) is very articulate about the role of relationships and social capital in the evolution of intellectual capital.

References

Allee, V. (2003) The future of knowledge: Increasing prosperity through value networks, Butterworth-Heinemann.

Alinsky, S. (1972) Rules for radicals: A pragmatic primer for realistic radicals, New York: Random House.

Aberdine, P. (2005) Megatrends 2010: The rise of conscious capitalism, Charlottesville: Hampton Roads.

Ayittey, G.B.N. (1992) Africa betrayed, New York: St Martin’s Press Inc.

Ayittey, G.B.N. (1999) Africa in chaos, New York: St Martin’s Press Inc.

Barrett, R. (1998) Liberating the corporate soul: Building a visionary organisation, Woburn: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Campbell, J. and Moyers, B. (1988) The power of myth, New York: Doubleday.

Capra, F. (1982) The turning point: Science, society and the rising culture, London: Flamingo.

Chappell, T. (1994) The soul of a business: Managing for profit and the common good, New York:Bantam Books.

Christie, P., Lessem, R. and Mbigi, L. (Eds) (1994) African management : philosophies, concepts and applications, Randburg: Knowledge Resources.

Coghlan, D. and Brannick, T. (2001) Doing action research in your own organisation, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Drucker, P.F. with Maciariello, J.A. (2005) The daily Drucker: 366 days of insight and motivation for getting the right things done, MA.: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

Greenleaf, R.K. et al. (1996) On becoming a servant leader, San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Hampden-Turner, C. and Trompenaars, A. (1993) The seven cultures of capitalism: Value systems for creating wealth in the United States, Japan, Germany, France, Britain, Sweden and the Netherlands, New York: Currency and Doubleday.

Gibson, R. (ed.) (1997) Rethinking the future: rethinking business, principles, competition, control & complexity, leadership, markets and the world, London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing Limited.

Harrison, L.E. and Huntington, S.P. (2000) Culture matters: How values shape human progress, New York: Basic Books.

Huntington, P.H. (1998) A clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order, New York: Simon and Schuster.