Prophecies And Protests ~ Manufacturing Management Concepts: The Ubuntu Case

We are not born simply for ourselves, for our country and friends are both able to claim a share in us. People are born for the sake of other people in order that they can mutually benefit one another. We ought therefore to follow Nature’s lead and place the communes utilitates at the heart of our concerns (Cicero, De Officiis I, VII: 22).

We are not born simply for ourselves, for our country and friends are both able to claim a share in us. People are born for the sake of other people in order that they can mutually benefit one another. We ought therefore to follow Nature’s lead and place the communes utilitates at the heart of our concerns (Cicero, De Officiis I, VII: 22).

Introduction[i]

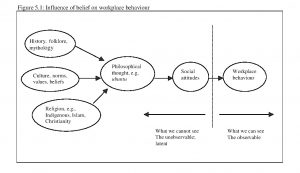

During the last decade ubuntu has been introduced as a new management concept in the South African popular management literature (Lascaris and Lipkin 1993; Mbigi and Maree 1995). ‘Even South Africa has made a contribution with the rise of something called ‘ubuntu management’, which tries to blend ideas with Africa traditions as tribal loyality’ (Micklethwait and Woodridge 1996: 57). Mangaliso (2001: 23) stresses that with the dismantling of apartheid in the 1990s, South Africa embarked on a course toward the stablishment of a democratic non-racial, non-sexist system of government.

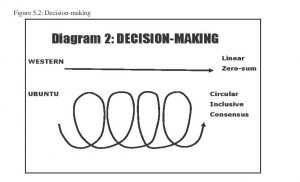

‘With democratic processes now firmly in place, the spotlight has shifted to economic revitalization’. To support this revitalization, ubuntu became introduced as a new concept to improve the coordination of personnel in organisations. Mangaliso defines ubuntu as humaneness, ‘a pervasive spirit of caring and community, harmony and hospitality, respect and responsiveness that individuals and groups display for one another’. In that sense ubuntu demonstrates family resemblances with Cicero’s communes utilitates. By using the Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars model of the seven cultures of capitalism, Mangaliso reviews the competitive advantages of ubuntu.

One of the themes within the model focuses on language and communication. Mangaliso (2001: 26) points to the fact that

… traditional management training places greater emphasis on the efficiency of information transfer. Ideas must be translated quickly and accurately into words, the medium of the exchange must be appropriate, and the receiver must accurately understand the message. In the ubuntu context, however, the social effect on conversation is emphasized, with primacy given to establishing and reinforcing relationships. Unity and understanding among effected group members is valued above efficiency and accuracy of language.

To that end – Mangaliso notices – it is encouraging to see that after 1994 some white South African managers have begun to learn indigenous languages to better understand patterns of interactions and deal with personnel appropriately.

With this mastering of language(s) Mangaliso stresses an intriguing point, which requires further exploration. He creates a contrast between traditional management approaches (like Taylorism and Fordism) and ubuntu. Whereas the former only focus on formal language as a means to transfer information in an efficient way, the latter is based on conversation. This contrast reflects an interesting debate, which actually takes place in the management literature. There is the modernist perspective that conceives management knowledge as a predefined, reified object adopted by organisations. At the other hand there is an increasingly popular perspective conceiving management knowledge as constructed via processes of diffusion like conversation (Lervik and Lunnan 2004). In this respect it can be noticed that over the last decade there has been a significant increase in the study of language in organisations (Grant et al. 1998; Holman and Thorpe 2003; Moldoveanu 2002). The research being conducted in this area is meant to be potentially useful to managers. In that context the initiative of those white South African managers to learn other languages can be positioned as a way to become better experts while designing an approach which strengthens their capability to calculate rational solutions to problems by improved manipulation. This kind of approach is, however, still managerialist in the sense that it embraces the traditional view that managers get things done through the actions of others. A lot of management concepts that have been developed over the last fifty years indeed reinforce managerial interests instead of being focused on broader managerial practices.

If, however, the mastering of languages is meant to let managers become good conversationalists who are both responsive listeners and responsive speakers in order to manage interactions instead of actions (Shotter and Cunliffe 2003), we are dealing with a different view on language. The purpose of speaking many languages then, is to achieve a commonly shared objective (Falola 2003). This capability to speak different ‘languages’ consists of showing how what is proposed by managers can fit everybody’s interests. This is what seems to be at stake with ubuntu. Ubuntu does not only enhance communication between management and employees but provides voice as well, i.e. a participatory interaction where openly conflictual social formation can occur, producing voice and inventive ways of living together (Deetz 2003).

This other view on the meaning of language can clarify how an effective implementation of ubuntu in organisations can be supported. Managers who are good conversationalists are able to tell a story, which does not only refer to the facts but can also be liveable for all those involved.

In the remainder of this chapter I would like to present my main argument about the relevance of a popular management concept like ubuntu for promoting more ‘Africaness of management’ by expanding on the role of language, i.e. communicative action. I first introduce a framework of management concepts to indicate how the transfer of knowledge is being shaped within the field of management and organisation studies. The proliferation of a wide range of management concepts has indicated an increasing sensibility for fashion within the domain of management knowledge. The function of these popular management concepts is to ‘help managers engage in a brief standing-back from everyday pressures’ (Watson 1994: 216) which will allow them to reflect, and may offer them a new vocabulary to frame their (interaction) differently. Although the framework I introduce is applicable to understand the diffusion of ubuntu, the concept itself invites managers to approach the workforce within their companies in a way that better fits particular African business practices. In order to explain this, the second section will discuss the penetration of some of the key ideas of the language philosopher Wittgenstein in the management and organisational literature. Usually the work of the latter Wittgenstein has been pinpointed as the inspiration for a so-called linguistic turn, which viewed language no longer as a representational device to inform us about the world but as a system of speech acts that through interaction between speakers and listeners provides meaning. Based on Wittgenstein’s view (1953) on language games it will be illustrated how even in instrumental organisations conversations take place and how these can change the role of managers. Finally I will relate the issue of ubuntu as a management concept that propagates a more humanistic view to the linguistic turn that the field of management and organisation begins to embrace in order to support the articulation of what sub-Saharan African countries have to offer to global management (Jackson 2004).

The transfer of management concepts

The description Mangaliso has given of Western managers striving for a proper efficiency of information transfer resembles Peter Drucker’s Management by Objectives (MBO). This management concept dates back to the 1950s and became one of the most fashionable concepts of the 20th century. At that time Drucker (1955) worked as a consultant for General Electric (GE) and noticed how its vice-president Harold Smiddy, who was in charge of the Management Consultation Services Division of GE, introduced MBO. Smiddy was convinced that the success of this large scale organisation was determined by persuasion, rather than by command, authority and responsibility of its managers. ‘Not customers, not products, not plants, not money, but managers may be the limit on General Electric’s growth’ (Smiddy 1955: 9). Peter Drucker has become famous for his way of transferring this management concept to the larger business community. He was able to describe, simplify and define MBO in a general way, using a language that was familiar to management. It strengthened the identity of managers as a profession. The concept itself obtained features that made it universally applicable. Due to specific political circumstances after World War II this and similar management concepts like ‘productivity’ were exported to the Western hemisphere. According to new institutionalists like DiMaggio and Powell (1983) the successful transfer of management concepts to all kinds of instrumental organisations can be explained by the functioning of coercive, imitative and normative mechanisms.

Certainly until the 1960s Europe and Japan were under the spell of the United States and its business approach became diffused by coercive and imitative processes like the Marshall Aid and the military occupation of Japan during the McArthur era (Djelic 1998). The development of Business Schools and their concomitant training programmes for future managers created a normative setting, which made it logical for the newly trained managers to transfer the best practices of American companies into their own practices. Management concepts which introduced production management, marketing and strategy obtained a design of universal applicability although a process of ‘Americanization’ was always present (Guillén 1994; Locke 1996; Djelic 1998). Let me illustrate this with one example.

Total Quality Management

Tsutsui (1998) has shown that the famous Japanese Total Quality Movement (TQM) was not the result of some specifically Japanese culturalist essentialism or capacity of imitation and mimicry, but the continuation of Taylorism in a different shape. The Japanese refinement of Scientific Management eventually systematized and disseminated as the Total Quality Control concept of the 1960s, which allowed firms to exploit the technical benefits of Taylorism while avoiding the determined opposition of workers and labor unions. While remaining consistent with Taylorite imperatives, ‘the Japanese practice of modern management ultimately traced a distinct trajectory of development’ (Tsutsui 1998: 11). Japanese management reformers – especially the Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers (JUSE) – never repudiated Scientific Management and its instrumental language of efficiency. They revised it into a local management discourse by enriching it with the rhetoric of participation, decentralization and motivation, and the gospel of small-group activities, as the Human Relations methods had propagated earlier. The workers’ full commitment to corporate goals was gained through subtle and consistent programmes of education and training during which conversations about new practices were organised. Some notable management concepts like MBO extended a ‘considerable long-term influence on the evaluation of Japanese quality thought’ (Tsutsui 1998: 220).

In the 1980s the Japanese TQM approach became a highly fashionable concept that was imitated everywhere. Locke (1996) indicates that it threatened to overthrow the American management mystique. But in the end it did not. The popularity of the Japanese management approach somehow amounted to a further expression of management’s international Americanization (Locke and Schöne 2004).

The impact of the Japanese management approach, however, could not be denied. It made clear that management concepts could not simply be transferred and adopted as if they had universal applicability. These management concepts had to be translated to make them relevant for local practices. Redefining American business practice was put on the agenda. The application of management concepts, respecting the local context and the capability of managers to translate any concept into an adapted form and to convince the workers of its relevance, became new topics.

Management fashion

In Beyond the Hype, Harvard Business School professors Eccles and Nohria (1992: 19) came to the conclusion that … in a nutshell, managers live in a rhetorical universe where language is constantly used not only to communicate but also to persuade and even to create. The first step in taking a fresh perspective toward management is to take language, and hence rhetoric, seriously.

With this statement the authors clearly distanced themselves from the modernist view on language as the chief and neutral means by which we inform others about the results of our observations and thoughts. They pointed to the fact that managers get things done through persuasive language. In management literature it became noticed that the popularity of management concepts like Total Quality Management (TQM), Business Process Reengineering (BPR), and Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) depended upon the way managers were able to persuade and convince people. These management concepts are, in general, still used as tools to improve business practices, which still comply with a managerialist perspective. However, in the context of communicative action, as will be argued in this chapter, management concepts may reshape business practices in a different way.

Since the proliferation of management concepts in the USA and their increasing transience as fads, research has endeavoured to examine the process of the constitution of management knowledge and its diffusion. In 1990, former McKinsey consultant R. Pascale for example, expressed his surprise about the tremendous popularity of certain management concepts. Reviewing the prevailing management literature he noticed the ebbs and flows of many business fads. Although he found this an alarming development, he had to admit that some of the management concepts that initially obtained faddish characteristics, like TQM, nevertheless stimulated serious consideration and have been adopted as an enduring way of doing business. Grint (1992) noticed in Fuzzy Management that for the business community, the issue is not whether management concepts are scientifically substantiated in the sense that their truth can be stated, but whether they secure business results that are currently accounted legitimate. Even if their scientific value cannot be proven, management concepts are apparently attractive as long as they seem to result in an increase in productivity, efficiency or performance. Czarniawska and Joerges (1996) are not so much worried about this phenomenon of fashion. It provides an opportunity for frivolousness and temporality and can challenge the institutionalized order of things. In the same vein Ten Bos (2001: 176, 179) defends the role of fashion in management:

Fashion provides us with a more aesthetic view of organisation and management and what it does not like is ‘fanaticism’. As a matter of fact it shares fundamental characteristics with the managerial work: fragmented, impermanent, volatile.

Regardless of this fashionlike appearance the point is to understand how a management concept is constituted. With regard to this the attention over the last years has shifted from diffusion to adoption of management concepts in instrumental organisations. According to Taylor and Van Every (2000: 79) these organizations should no longer be seen as purely physical entities, but primarily ‘as territory, a partly physical, partly social life space occupied by a diverse population of workers, managers, and other interest groups, each with their own agendas’. Writing the map of the organisational territory is the principle activity that is taking place. In other words, the principle activity of organisations is repairing, correcting deviations from the map or changing the map.[ii] Such a map is as much inscribed in texts as in conversations. The basis of the organisation-as-text is a description in a symbolic language and therefore obtains a material basis. The organisation-as-conversation is shaped through talk-in-interaction.

Main characteristics

Management concepts are usually born as mental creations, ‘constituents of thought’ (Fodor 1998: 23), about specific processes in organisations. Initially managers facing a problem may discuss their ideas amongst themselves, like at the classical Greek agora. The words they use express new ideas which can support managers to get things done. Where these ideas exactly come from and how they turn into knowledge are complex issues. Nohria and Eccles (1998: 279 and 298), conclude the following:

If asked, most people would tell an interesting story about the variety of sources that have contributed to the ways they act and think as managers. Indeed, management knowledge comes from everywhere: it comes from a manager’s own experience, from books and articles on a variety of topics … and increasingly from consulting firms.

The most remarkable fact, however, is that the popularity of management concepts has much more to do with the quality of the source providing the concept than with its truth.

Managers are interested in ideas which are established by the reputation of a particular country (e.g. Japan), company (e.g. General Electric), manager (e.g. Jack Welch), consulting firm (e.g. McKinsey), educational institution (e.g. Stanford), or professor/ consultant (e.g. Peter Drucker). That is the source of a particular concept.

Considering the previous analysis, four characteristics of management concepts can be identified (Karsten and Van Veen 1998):

A. Management concepts usually have a remarkable label such as TQM, BPR, Core Competency or Knowledge Management (KM). Whenever possible these concepts are reduced into acronyms, to make them convincing and persuasive within the language community of management, and to help create specific networks of professional managers sharing the same discourse.

B. Management concepts describe in general terms specific management issues, which cause an increase of costs or a loss of customers. Managers are then faced with an irresolute but pressing problem that calls for a new meaning and thus are compelled to develop a more probable course of action to improve the situation. Concepts can frame a particular organisational problem and make it recognisable for the managers involved. For example, BPR will be seen as a useful analysis because it allows managers to identify the actual company structure, which has to be redesigned.

C. Management concepts offer a general solution to identified problems. They do not provide constitutive rules, which prescribe relatively specific actions to be taken, but general guidelines that bring about mutual orientations between actors. These guidelines suggest a standard of conduct (protocols) and propel action in a certain direction. They usually evolve from the values and practices of the specific community of actors where the concept initially had been developed. The guidelines are generally issued as a provisional measure until more is known about the practical usefulness of a concept. For example, BPR justified its interventionist guidelines by stating that companies with obsolete structures will become more efficient once these structures have been redesigned and modern information and communication technology has been introduced. But to persuade managers to follow those guidelines, another characteristic has to come into play:

D. The proposed solution will be promoted by referring to success stories about specific well-known firms, which have either developed or already implemented the concept. GE, IBM, Shell and Toyota are usually portrayed as convincing examples of the success of a concept. The examples are the narratives, i.e. the evidence-based stories (Sorge and Witteloostuijn 2004), which articulate the knowledge employed in particular situations and have subsequently created new best practices. The advantage of storytelling is that it facilitates social interaction. At the company level managers can easily share these stories and promote conversations that create beliefs in a common reality which, in turn, becomes a symbol of group solidarity. The different meanings that can be given to the examples can be seen as an invitation to establish a shared translation, which is an act of political persuasion to enrol support for a concept (Tsoukas 1998). The examples themselves illustrate how at the right time (kairos), these instrumental organisations like GE or Shell took the opportunity to introduce a new concept (Miller 1992). Finally, these conversations about company successes will invoke ‘a common reality, or myth, which may or may not be true; this is what stories and narratives do’ (Hardy 1998: 68).

These four characteristics make a management concept recognisable and clarify how a common social reality about a specific management practice becomes shaped. The fact remains, however, that the knowledge contained in a management concept does not provide constitutive rules according to which a successful implementation can be deduced. Although the above characteristics B and C may suggest that there are rules involved as impersonal, generic or temporal formulae to identify a problem and solve it, these rules are no more than guidelines. Even management concepts that are reshaped into management models with clear graphical designs to illustrate how these concepts should be applied do not provide a detailed prescription for their implementation (Have 2003). These models are only composed of ‘structured knowledge’ (De Long and Fahey 2000).

Diffusion

After the ‘fad and fashion’ characteristics about management concepts had been detected and recognised, research has begun to study from a new perspective the diffusion mechanisms developed by DiMaggio and Powell. Especially the role of diffusion agents, i.e. consultants and gurus, has become the object of analysis. Their rhetorical, linguistic and dramaturgical performance qualities have been stressed (Abrahamson 1996; Huczynski 1993; Clark 1995; Kieser 1997; Grint and Case 1998).

Within the specific institutional contexts that facilitate the transfer of management concepts from one place to another (or from one country to another) a market of management concepts has been established, where these professional diffusion agents play an extremely important role. Although gurus and consultants are both disseminators who try to persuade their clients to follow the concepts they propose, gurus usually present their views through monologues whereas consultants prefer the dialogue. In both cases, however, the purpose is to introduce the new management concept as a novel label to identify an issue that managers may experience as problematic. This amounts to offering a way of making sense of what happens in a specific situation that created the problem. Consultants and managers may then together frame and define the actual situation as well as the preferred one. They tell stories to each other in potentially multiple ways, each way corresponding to a different portrayal of the organisational landscape that caused the particular problem.

Since organisational routines are deeply embedded in organisational cultures and in shared mental models, it is extremely important to initiate discourses among organisational members, in which current structures and practices are questioned or reinterpreted and alternative, more appropriate management philosophies and approaches are offered in a rhetorically convincing way (Kieser 2002: 217).

Consultants may finally influence managers to accept one meaning of the management concept over another. A translation takes place, which will not only lead to new knowledge but to a new management practice as well (Cooren and Fairhurst 2003).

While the level of truth of the management concept can only be stated in terms of plausibility and evidence-based stories, the management concept is usually accepted and implemented due to the communicative skills of the consultant to influence and persuade. These interactions constitute a language game, that takes place between consultant and manager(s) with either the consultant’s strategic intent to let the manager accept the relevance of a particular management concept, or a conversation where consultant and manager jointly agree and engage in the implementation of a particular concept. Language used in this context is quite distinct from the traditional view about language as a neutral mechanism to convey viable information, based upon a proper picture of facts. To better understand this dialogic view on language, it is time to look at the impact of the latter work of the language philosopher Wittgenstein.

The role of language

The work of the language philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein about the meaning and use of language in the 1950s served to refocus the very course of modern philosophy thought in the West away from a theory on knowledge to the study of meaning. Initially the young Wittgenstein shared with representatives of the Vienna Circle the belief that words stand for things and depict them in place of the actual phenomenon. For the logical positivists of the Vienna Circle sentences have meaning in relative isolation from the settings in which they are used. In other words: sentences have meaning if and only if their truth-condition can be established. Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) was linguistic in the sense that it focused on therole of propositions: sentences in their projective relation to the world (Hacker 1997). The meaning of the word is found in the object for which the word stands. For example, once the words and sentences used for example to indicate the goal of a firm have been stated clearly and are properly repeated by managers and other employees, a CEO can be convinced that s/he coordinates effectively. This is the conviction Drucker expressed with his MBO. The words and sentences that are used, picture facts and clarify as such the correspondence with the reality of the firm.

The later Wittgenstein repudiated the principles he had laid down in his earlier work. In his Philosophical Investigations (1953) he recognised that certain pictures are incomplete and distorted. He came to the conclusion that there is not a simple relationship between the name and its bearer. A word’s meaning is related to its practical use. One cannot know the meaning of words without knowing the context within which the word is used. In other words: ‘One can know the meaning of a word only if one knows how it is used in practice’ (Watson 1997: 364). The way a word is used, and thus its meaning, is contingent on the situation in which it is used. Wittgenstein therefore diverted his attention from the question of truth to that of meaning and concluded that language does not gain its meaning from its reference but from its use in action. Language games became his key focus of attention. Wittgenstein’s new vision on language games with their own set of rules caused a linguistic turn in western philosophy in the sense that language was no longer simply seen as a representational device to inform us about the world.

Instead of focusing on the solitary act of a speaker saying something about the world, the attention shifted to the social act of a speaker saying – through speech acts – something about the world to a listener in order to develop a shared meaning.

Language

was no longer valued as a neutral mechanism through which words and sentences provide true knowledge, but as a system of speech acts, that through interactions between speakers and listeners and their reciprocal interdependencies, provides meaning (Moldoveanu 2002).

Speech acts

Philosophers like Austin (1975, originally 1962) and Searle (1969) who explored Wittgenstein’s view on language games looked at sentences not as artifacts that carry meaning ‘on their own shoulders but as issuances by speakers for the benefit of their hearers’ (Fotion 2003: 34). Austin claimed that besides the description of reality, language is used to perform speech acts. Sentences, i.e. utterances, only carry meaning when the role of the speakers and the hearers, and the rest of the context, i.e. a shared background, are taken into account. Together these sentences constitute a miniature civil society, a special kind of structured whole, embracing both the one who initiates it and the one to whom it is directed.

Austin and Searle developed a speech act theory to look for the rules according to which language itself is being applied to provide meaning. Austin came to the conclusion that all utterances are performative in nature, be they of an asserting, insisting, promising, commanding, warning or flattering kind. Performative utterances are a kind of action, which brings about some result. The speech acts themselves cannot be evaluated as either true or false. It is Searle’s achievement to give substance to Austin’s idea of a general theory of speech acts by introducing five different categories (assertives, commissives, directives, expressives and declaratives) to classify the illocutionary forces of utterances. If for example a medical doctor issues an order to a nurse by a directive, obedience is required. The claim of the speech act fits particular constitutive rules. Searle introduced a distinction between regulative and constitutive rules within a language game. Constitutive rules define forms of conduct. The rules of chess for example create the possibility for players to engage in playing chess. They act in accordance with the given rules. How they perform in the game itself depends on their mastering of regulative rules. Searle’s central hypothesis is that speech acts are performed by uttering expressions in accordance with central constitutive rules. When a speaker engages in promising something (a commissive speech act) he thereby subjects himself in a rather specific way to the corresponding system of constitutive rules. While acting in accordance with constitutive rules, certain special rights, duties, obligations and various other prescriptions are imposed on our fellow human beings and ourselves and on the reality around us. Four important rules are that the speaker commits himself to what s/he says, has evidence of what s/he says, provides new information and believes what s/he says.

With these four rules at hand Searle is convinced that the speaker will speak the truth about a fact or state of affairs. Searle’s focus is therefore still to use the speech act theory to clarify how truth comes about. But a significant drawback of Searle’s theory is that it does not adequately consider what makes a speech act successful. This problem has to do with the fact that Searle does not take into consideration the role of several different validity claims that are at stake (Smith 2003). Within the context of using a management concept which defines a specific situation in a company, the role of different validity claims is very relevant. To justify the validity of a management concept storytelling seems to be an appropriate practice. Storytelling in the form of biographies, fiction or historical novels is, however, composed of a wording that may not be completely true but nevertheless persuasive, plausible and convincing. Searle has put fiction aside as a parasitic form of speech acts because he only focuses on the validity claim of truth. Fotion (2003) does not agree with this distinction and is convinced that speech activities like storytelling do not fully jeopardize these rules but that they have to be seen in a different context.

Communicative action

The linguistic turn has readdressed the attention to language and has admitted that rhetorics and persuasion are key features to understand how the meaning of what is being said is shaped. Initially the interest focused on the intention of the speaker. It was paying attention to the way a speaker was talking at people rather than with people.

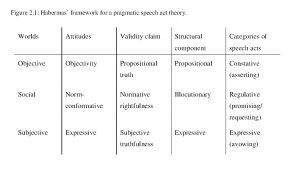

The work of a number of dialogic theorists (Habermas 1984; Bourdieu 1998; Taylor 1995) has turned the attention to the role of language within the interaction between speaker and listener. Dialogic theorists stress the importance of language in the construction and reconstruction of social reality. It also recognises that heterogeneous discourses are the norm. So long as we engage in communicative action, we are embedded in a dialogic interaction that continuously shapes and reshapes speakers as well as listeners. The work of the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas is extremely relevant to clarify the role of communicative action. Later on in this chapter it will help us to understand the role ubuntu can play in organisations. Habermas’ Theory of Communicative Action (1984-1987) provides a broad framework, which includes as much the speech acts of Searle as the speech activities Fotion discerned, which do not fully comply with the four rules about speaking the truth. Instead of referring to one world with regard to facts and states of affairs as Searle does, Habermas introduced four different validity claims. A speaker who is oriented towards mutual understanding, will raise several different validity claims and will presuppose that the listener will accept these validity claims. Successful communication implies that the listener must both comprehend and accept a speech act. Next to the claim of comprehensibility there are three important claims at stake:

– A claim which refers to the outer states of affairs which a listener may explore as truly or falsely existing;

– A claim which invokes contextual norms that legitimize the action which is being undertaken, i.e. norms to which listeners may consent as appropriate to the situation at hand or may challenge;

– A claim expressing the inner state of self, emotions and dispositions such as seriousness, anger, impatience or frustration which a listener may trust as authentic or challenge (Forester 1992).

These three validity claims relate to three worlds Habermas has discerned: the objective, the social and the subjective. To all three worlds every speaker and listener has a specific attitude:

– When a speaker adopts an objectivating attitude he relates to the objective world of facts and existing states of affairs.

– When a speaker adopts a norm-conformative attitude he relates to the social world of normatively regulated interactives.

– When he adopts an expressive attitude, he relates to the subjective world of inner experience (Cooke 1994).

Any speech act – including speech activity – is successful if an actor relationship is established that is based on mutual understanding, i.e. the four validity claims are being respected. Habermas’ point is that the illocutionary force of speech acts is constituted by the mutual recognition of the four validity claims. According to Habermas Searle has not analysed the reasons and motives that would make the listener accept the speech act (Habermas 1989).

These validity claims (comprehensibility, truth, rightfulness and truthfulness) can help us understand how a consultant and a manager or managers amongst themselves in a team reach consensus through dialogue/conversation about the applicability of a management concept by respecting all the validity claims. A conversation is a kind of communicative action, which is usually defined as a range of actions towards agreement or mutual understanding (Verständigung). The goal of communicative action is to coordinate the speech acts of the participants. Habermas’ focus is on the pragmatic aspect of language, i.e. how language is used in particular contexts to achieve practical goals. The consultant and the manager do this more in particular at the level of the social and the subjective world. While a consultant talks about a management concept in an ‘experience-distant way’, the manager on the other hand talks about the same management concept in a ‘experience-near’ way. Managers prefer to deal with concepts in a perceptual way and look for applicability (Cf. Geertz 1979).

Their communicative actions do not directly change the objective world of facts and states of affairs. But once an agreement is reached a manager will subsequently behave in line with the meaning he has given to the management concept and instruct his subordinates to do the same. Only then the objective world of facts can be changed. By definition this procedure also holds true in case a manager starts a conversation with his subordinates to solve a problem. Once they have reached an agreement the subordinates are the ones who do and intervene in the physical world to change things. In this sense Habermas defends a clear distinction between interaction and work.

Strategic action

To achieve the practical goal of implementing a management concept, however, social actions can be divided in strategic and communicative ones. If a manager makes his subordinates accept a management concept without mutual understanding, but for example ‘seduces’ or misleads them to implement the concept, then force – a power relation – is the means of coordinating the social action. In strategic action the manager strives at his own private goal without restraint. What matters for the manager is how he can use the employees to realize his own private goal by ‘selling the concept’. This practice is called a distorted or hampered conversation. It is usually shaped in the form of a monologue and leads to manufactured consent. The management concepts used in such an atmosphere are designed, used and applied as monologic tools and underpinned by a technical-instrumental rationality. Habermas rejects this as a naïve premise as if merely talking to one another will lead to a better world. In the situation of communicative action the manager as well as the subordinates comprehend and accept the relevance or the validity claims through which the importance of a management concept is being presented. They will then jointly implement the management concept.

The communicative action includes, so to say, the speech act and the material act. In communicative action the actors are performing actions, which lead to material acts in the objective as much as in the social world (engagements) while not breaking the mutual consensus and legitimately created social relationship between them. Habermas’ distinction between strategic and communicative action points to the fact that a speech act can both be used for reaching mutual understanding and with a strategic intent.

The communicative action, however, consists of:

– A level of mutual understanding, based on a shared background which is obtained by means of an open conversation through regulative speech acts;

– An operational level (the material part) – based on the consensus reached by constative speech acts which lead to instrumental i.e. material actions.[iii]

The communication model Habermas has developed is of interest because it makes us realise that, for the validity of a management concept, it is not enough to only focus on its propositional truth. Management concepts are full of storytelling and their impact cannot solely be judged on their claim of truth. They have an impact on how we perceive and experience reality because – as the model shows – it is also crucial to have knowledge about the social and subjective world when we want to analyse human communication and social interaction, a knowledge that also has to be understood in terms of normative rightfulness and truthfulness. Communicative action is thus a multi-layered approach which sets the scene for engagement to apply and implement a management concept. It recognises a difference between subscribing to the objective world (a description of facts and states of affairs as they are), the social world which characterizes interactions as they should be and a subjective world, a view about how people experience the world they live in.

Conversation

As I have argued so far, studies of conversations need a linguistic analysis, which is rooted in the philosophy of language, but this is not sufficient. Speech act theory in general is very much focused on monogolism and portrays the agent as an autonomous information processing organism. The focus is on analysis of sentences as autonomous units. However, Habermas’ pragmatic theory of communicative action has extended the framework into dialogism which takes actions and interactions, e.g. the discursive practices, in their context as basic units. According to Linell (1998: 11) Searle still ‘pictures the speaker as an entirely rational agent’, and stresses ‘the rationality, efficiency and logos of the single idealized communicator’. That approach stands for a monogolism, ‘which sustains the authority and domination of the speaker at the cost of his partners, the listeners’. Whereas strategic actions suppress negotiations of meaning, vagueness, ambiguity, polyvocality, domination and fragmentation of participation, Habermas defends a normative approach to dialogue, stressing mutuality, openness, consensus and agreement. To understand the intertwinement between discourse and context, content and expression, speaker and partner, cognition and communication, conversational analysis is needed. Such an analysis is rooted in an empirically oriented sociology of language that started with ethnomethodology (Cf. Silverman 1998; Samra-Fredericks 2000). Conversational analysis focuses on where and how, in everyday life in instrumental organisations, i.e. the context, people routinely group the sense of each other’s talk-based performances. The purpose is to understand the socio-historically determined institutional context within which specific statements occur. This context provides actors with a shared understanding of a situation. In terms of Wittgenstein, the actors identify the situation they are in as the common language game. Knowing in which game they are, determines what is appropriate behaviour. Habermas defines this context in a broader sense as the life world, which contains all the implicit backgroundknowledge about personal identity, culture and society. These life world phenomena cannot be excluded from instrumental organisations. Those organisations that are operating in a multicultural context will have to cope with different communal backgrounds and that makes them differ in interpretations of facts/states of affairs, conventions, norms, procedures, routine actions as well as improvisations.

Although conversations and dialogues are fuzzy constructs, they are language-based interactions, which permit shared meaning to emerge (Grant 1998: 6). The way a shared meaning occurs, however, depends upon the way this medium is used in an instrumental organisation. Conversations can aim for agreement and promote dialogue for mutual understanding, without excluding for that matter that heterogeneous discourses are the norm.

A dominant view in the Anglo-American literature suggests that Western instrumental organisations predominantly implement management concepts through techniques and tools such as cultural re-engineering, quality management, autonomous work teams, just-in-time production systems and employee-involvement programmes to disguise tensions and conflicts. The purpose of these techniques and tools is to establish a specific corporate ideology, a belief in the effectiveness of a concept (Cf. Reed 1998: 201). Usually the regulative and expressive speech acts used are of a strategic kind and commit the hearer to carry out the action represented by the propositional speech acts.

The normative rightfulness of the speech acts as delivered by the manager are not being questioned. Only stories from management’s perception are being told to ensure that meanings and motives for action are circumscribed and regularized according to his perspective. In that sense talking at people rather than with people prevails.

However, as has been stated earlier, the recent literature on discourse and dialogues in relation to management practices indicates that conversations, which are based on open communicative action, stress the dialogical perspective. This offers all participants in instrumental organisations to relate with each other by shaping and reshaping a management concept. This entails the recognition of moral interdependence and allows stories from the employees’ perspective about specific management practices to be integrated. This kind of conversations as ‘talk-ininteractions’ (Taylor and Every 2000) looks at an instrumental organisation as a linguistically constituted community in the sense that there always is an explicit enactor i.e. the manager, but that it is the community of standard enactors, who actually implement a management concept. In the absence of such a community the enactment would be undefined and would thus not exist as enactment (ibid.: 270).

Taylor and Every (ibid.) notice that in the dominant Anglo-American management literature the perspective to perceive enactors as a strategic means to reach a goal, is still prevalent. The now popular talk about employees as human resources typifies this approach. People are just another resource to meet the objectives of the instrumental organisation. Within such a context, communication is limited to its strategic version.

Ubuntu and communicative action

Recently, Jackson (2004) has reviewed an upcoming process of Africaness of management and introduced in that context a humanistic view of people to oppose this strategic view. He sees people as having a value in their own right and an end in themselves. Ubuntu encapsulates this approach. Even if it may sound somewhat idealistic – as Jackson says – ‘to try to identify a particular African style or even philosophy of management … any description of management systems within Africa should include a consideration of an indigenous African management’ (2004: 26-28). And he believes that ubuntu reflects this approach.

While agreeing with Jackson one can see ubuntu as a way to promote and strengthen an attitude of open conversations, as Habermas propagates. In that sense ubuntu can reflect a critical discourse because it wants to include the voice of all participants in any instrumental organisation.

In the South African tradition, it is the community that shapes the person as person. The meaning of ubuntu is illustrated through the Xhosa expression ‘Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu’ meaning the person is a person through other persons, and this expresses a typical African conception of a person. Ubuntu provides a strong philosophical base for the community concept of management (Khoza 1994). Mbigi (1997) has listed the following relevant principles of ubuntu: the spirit of unconditional African collective contribution, solidarity, acceptance, dignity, stewardship, compassion and care, hospitality and legitimacy. Ubuntu intends to reflect an African attitude that is rooted and anchored in people’s daily life. The expression of a person as a person through persons is ‘common to all African languages and traditional cultures’ (Shutte 1993: 46). Ubuntu is a symbol of an African common world and the concept has namesakes in different terms in African countries. Mogobe B. Ramose (1999) made a relevant remark by saying:

African philosophy has long been established in and through ubuntu. That here not only the Bantu speaking ethnic groups, who use the word ubuntu or an equivalent for it, are referred to, but the whole population of Sub-Saharan Africa, is based on the argument that in this area ‘there is a family atmosphere, that is, a kind of philosophical affinity and kinship among and between the indigenous people of Africa’.

In West Africa, more in particular in Senegal, the concept of ‘teranga’ reflects a similar spirit of collective hospitality between people. Zimbabwe’s concept of ‘ubukhosi’ also mirrors itself metaphorically in the statement ‘umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu’. There are apparently similarities between these concepts and that of ubuntu, which reflects an African view on community, and is embodied in customs, institutions and traditions (Karsten & Illa 2004).

According to Shutte (1993), ubuntu is not synonymous with either Western individualism or collectivism. Ubuntu expresses an African view of the life world anchored in its own person, culture and society, which is difficult to define in a Western context. According to Sanders (1999), the Zulu phrase ‘umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu’ has an economy of singular and plural not captured in the banal ‘people are people through other people’. The translation of ubuntu can sound like:

A human being is a human being through human beings or the being human of a human being is noticed through his or her being human through human beings … The ontological figure of ubuntu is commonly converted into an example and imperative for human conduct.

Ubuntu is enacted in African day-to-day actions, feelings and thinking. The African community as a social entity, however, is constantly under construction. It is an attempt to shape indigenous social and political institutions, which will be able to develop African nations and African civil societies.

Although ubuntu represents a specific African worldview, Mbigi (1997) is convinced that it nevertheless can be translated into what he calls The African Dream in Management. Ubuntu refers to the collective solidarity in Africa, but it can find its concrete expression in modern forms of entrepreneurship, leadership, business organisations and management. The introduction of ubuntu as a management concept will not replace the transfer of knowledge, i.e. management concepts, from the Western world but can support the development of a hybrid management system operating in Africa within which these Western concepts can obtain their proper African translation.

A proper African management system – like the American and Japanese ones – will generate a variety of management styles as distinctive sets of guidelines, written or otherwise, ‘which set parameters to add signposts for managerial action in the way employees are treated and particular events are handled’ (Purcell 1987: 535).

Ubuntu as a management concept intends to be more than just a popular version of an employee participation programme defined by the interest of management. Ubuntu strives to reach beyond a purely managerialist approach and includes the building of consensus. Looking at the reconstruction Ayitty has made of consensus building in indigenous African political systems, similarities can be found with the approach ubuntu propagates. ‘Coercive powers were generally not employed by the chief to achieve unity. Unity of purpose was achieved through the process of consensus building’ (Ayittey 1991: 100). Majority of opinion did not count in the council of elders: unanimity was the rule. In face-to-face communities in control of their own destinies these ‘wisdom circles’ were widespread. In these wisdom circles people rarely engage in responding directly to what is said with argument and debate. ‘Rather what is sought is a deepening of understanding and the spontaneous emergence of a solution or decision’ (Glock-Grueneich 2003: 36). Even if it is difficult to introduce the traditional form of wisdom circles in modern instrumental organisations, an adapted version can certainly help to shape an ubuntu approach in firms.

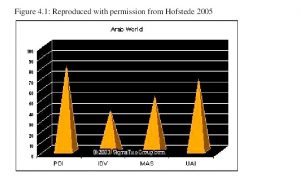

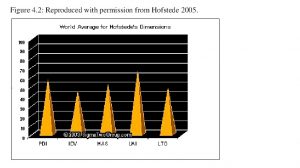

Scepticism about a suggested prevalence of ubuntu in African companies, however, cannot be denied. Jackson (2004) indicates that African organisational cultures and management styles with a predominantly strategic orientation are widely present and some of these management styles are often seen as rigid, bureaucratic, directive and task-oriented. Van der Wal & Ramotschoa (2001: 4) notice that ubuntu is sometimes popularised in business books reflecting the tendency to align it with productivity improvement and worker motivation techniques, which reduces its significance ‘to flavour of the month status’. They urge to prevent ubuntu from quickly obtaining a faddish character and believe that ‘ubuntu embraces a set of social behaviours like sharing, seeking consensus and interdependent helpfulness which, if recognised, valued and willingly incorporated in the culture of organisations, could exert considerable positive outcomes on business results’. Of course, Van der Wal and Ramotschoa’s fear can be related to the fashion-like character in which management concepts are ingrained. Even as a fashion – as Ten Bos (2000) has argued – ubuntu can enable managers to become sensitive to their own roles in a turbulent and ever-changing environment. The kind of sensitivity that may come out of ubuntu will depend upon the way managers apply this management concept: either in strategic or communicative action. If they apply it in the former way, then ubuntu will serve as a tool in a monologue; if it is applied in the latter ubuntu can provide a sound basis for constructive conversations about the common interests of a firm. This is the application of ubuntu that Habermas propagates. While ubuntu contains key features to reinforce communicative action and conversation it resists the purely formal language of Taylorism.

Ubuntu as a management concept

The purpose of ubuntu as a societal value is to reshape social relations in society and in instrumental organisations. If for whatever reason managers deny this purpose, they will indeed limit ubuntu as a management concept to a strategic i.e. managerialist use for specific goals they have defined themselves (Rwelamila, Talukhaba and Ngowi 1999). Habermas (1984) describes such an approach as a strategic action where the diagnosis and the solution of a problem within the organisation is not being shared and commonly performed by all participants. It then is a prerogative of management to set the objectives and forces others to accept them.[iv] If, however, ubuntu is based on communicative action and managers embracing ubuntu support that form of social interaction then it can lead to an engagement-stimulating democratisation within instrumental organisations.

Ubuntu can obtain the status of a management concept, when it fits the characteristics given earlier:

– Ubuntu has a striking label;

– Ubuntu already has raised in general terms a specific management issue. ‘Black managers and professionals need to develop a strong sense of collective social stewardship … We need a strong sense of collective, social citizenship’ (Mbigi 1997: 38).

The tendency to establish solidarity will build ‘a culture of empowerment and team work in the workplace’ (Mbigi 1997: 5);

– Ubuntu’s solution is to improve the efficient and effective operations of instrumental organisations in the South African context.

Literature begins to provide numerous success stories, but none of them seems yet to reach the status of the key success story. There is for example the case of Durban Metrorail, which adopted ubuntu as one of its guiding principles and made the company the Most Progressive Company in Kwazulu-Natal.[v] Patricia P. and A. Secheraga (1998) on the other hand consider the South African Airway to be the best example to illustrate how a major non-American corporation uses the various dimensions of ubuntu. Another interesting case for the implementation of ubuntu is CS Holdings.[vi] The staff of CS Holdings believes that ‘the reputation of a company as perceived by the market is as important as the actual services rendered by the company’. CS Holdings obtained its reputation as a new South African IT company, which forms alliances with firms such as Ubuntu Technologies to provide ‘expertise and knowledge exchange as well as some infrastructure, enabling Ubuntu Technologies to tender for business from which they were previously excluded’. The integration of ubuntu guidelines made it possible for CS Holdings to improve its management style and its performance.

Even if a positive impact of ubuntu guidelines can be contested, Chanock (2000) is right that the need to fight for different experiences, as they are reflected in other organisational cultures like Japan, is even greater for vulnerable indigenous communities in a global economy where Western views still dominate. Regardless of the fact that ubuntu can be abused for political reasons, it should be acknowledged that an indigenous South African management system is in its hybrid phase and that there is a tendency of ‘crossvergence’ which can support the development of a particular value system as a result of cultural interactions (Jackson 2004: 30). The hegemony of the modernist Western management approach generally has ignored those local cultural values. In the process of changing that modernist perspective, ubuntu may provide a solution to the problems African instrumental organisations face.

Conclusion

There is an increasing interest to promote ubuntu as a management concept. This chapter has tried to describe the main characteristics of management concepts, the way they are created, diffused and implemented. Within management literature the role of fashion cannot be denied and even offers opportunities for management concepts to become popular. It is the author’s view that a proper understanding of the promulgation of these concepts is best served by deepening our knowledge about the role language plays. Since the linguistic turn, the philosophy of language has extensively contributed to the advancement of this knowledge. The pragmatic theory of communicative action Habermas has developed clearly describes which claims are at stake to make a management concept meaningful. Next, his analysis stresses the fundamental distinction between strategic and communicative action which can be seen as the distinction between monogolism and dialogues/conversations. Dialogic theorists stress the importance of language in the construction and reconstruction of social reality. As far as we engage in communicative action – even with heterogeneous voices – we are embedded in a dialogic process that at the normative level is committed to restructure the public sphere in a more democratic way. Jackson believes that for the development of an Africaness of management the strengthening of a humanistic view of management is important. This view sees employees as having a value in their own right and as such can distance itself from the strategic view in organisations which only perceives people as a means to an end. Ubuntu encapsulates this humanistic view and for that reason is attracting quite some attention. Ubuntu is being positioned as a new way to strengthen the economic revitalization of Africa. To attain that goal an Africaness of management is quintessential. Mangaliso is of the opinion that to that end the craze for efficiency and accuracy of language has to be countered by an emphasis on conversation. With ubuntu, African managers may better master a relationally responsive understanding than one can find amongst Western managers, while the latter are usually professionally trained as accountable persons and manage employees more in a strategic way. Mangaliso refers to a distinction between accuracy of language on the one hand and conversation on the other. This chapter argues that it is not language as such which is at stake, but only the version that was developed in logical positivism developed and that found its way in Taylorism and Fordism. Since Wittgenstein has entered the field of management and organisation studies, this view of language is being revised. The pragmatic theory of communicative action provides an interesting basis to relate the issue of language to that of conversations.

Another point is that the possible impact of ubuntu in Africa is often compared with a similar success of Total Quality Management (TQM) in Japan. As Tsutsui (1998) has shown, however, TQM neatly fits into the Taylorist tradition which puts a dominant value on efficiency and the concomitant structuring of organisations and behaviour of managers and other employees. The conclusion from that example is that ubuntu as a management concept for instrumental organisations cannot be developed in the void. African firms and companies too will have to respect efficiency criteria to compete in the global market, but their shape, content and functioning can be adapted to the context shaped by ubuntu.

Quite some defenders of ubuntu as a management concept state that it is part of a development that has its roots in an African Renaissance. This African Renaissance functions like an agora of ideas that will promote a variety of social movements and support the shaping of African civil societies. Some of its ideas stimulate the articulation of an Africaness of management. Hopefully, those ideas will enter the market of management concepts, change the dominant strategic approach towards people in organisations, and offer new perspectives on global management. Mphahlele (2002) has indicated that there are similarities between European and African humanism.

Areas we share with Western Humanists amount to the value and love of life which we cherish; openness of mind; love of self which refuses to be shackled in stiffing, suffocating codes of conduct laid down by some authority who commands obedience; and a conscience that emerges from one’s own character as a social being responsible to the community, rather than a conscience that is built on the fear of authority.

These values which are now promulgated in ubuntu reflect interesting similarities with the development of European Renaissance in the fourteenth century. One of the authors frequently quoted at that time was the Roman Cicero (Skinner 2002). That is why this chapter started with one of his statements. This is not to say that there is one fixed human nature to which these values refer. It only stresses the point that human beings have some common human nature, which is best characterized by the fact that we are conversational beings. Without the latter there would not be the possibility of intercommunication, on which all thought, feelings, imagination and action depend.

NOTES

i. I gratefully acknowledge the comments of Henk van Rinsum (Utrecht University) and the editors of this volume. Of course, the usual disclaimer applies.

ii. Compare Habermas (1989: 141): ‘Die kartographische Abbildung eines Gebirges mag mehr oder weniger genau sein – wahr oder falsch sind erst die Interpretationen, die wir auf den Anblick der Karte stützen, ihr sozusagen, entnehmen’.

iii. In Habermas’ analysis Searle’s assertives are equal to constatives like ‘I say that this management concept is applicable’; Searle’s regulatives are composed of commissives, declaratives and directives.

iv. During the XI conference of the Eastern Academy of Management which was held in Capetown (South Africa) from 26 to 30 June 2005, Dorothy Ndletyana reported about her research within Deloitte to integrate ubuntu within the company practice and the resistance she encountered amongst the white managers of Deloitte.

v. Durban Metrorail is a South African public transport company. It received an honourable mention during the Black Management Forum (1999) for the most Progressive Company in Kwazulu-Natal.

vi. CS Holdings is a South African IT firm. For more information, please refer to: www.cs.co.za/ reconstructionand_development.htm

References

Abrahamson, E. (1996) Management fashion, Academy of Management Review, 21: 254-85.

Alvesson, M. and Willmott, H. (1992) Critical management studies, London: Sage Publications.

Austin, J.L. (1975) How to do things with words, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ayittey, G.B.N. (1991) Indigenous African institutions, New York: Transnational Publishers.

Bourdieu, P. (1991) Language and symbolic power, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Chanock, M. (2000) Culture and human rights; orientalizing, occidentalizing and authenticity, in M. Mamdani (Ed.), Beyond right talk and culture talk, New York: Saint Martin’s Press.

Cicero (1966) De Oficiis, edited by H.A. Holden, Amsterdam: A.M. Hakkert.

Clark, T. (1995) Managing consultants: Consultancy as the management of impressions, Buckingham: Open University Press.

Cooke, M. (1994) Language and reason. A study of Habermas’ pragmatics, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cooren, F. and Fairhurst, G.T. (2003) The leader as a practical narrator: Leadership as the art of translating, in D. Holman and R. Thorpe (Eds), Management and language, London: Sage Publications.

Czarniawska, B. and Joerges, B. (1996) Travels of ideas, in B. Czarniawska and G. Sevón (Eds) Translating organisational change, Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

Deetz, S. (2003) Reclaiming the legacy of the linguistic turn, Organisation, 10(3): 421-9.

De Long, D.W. and Fahey, L. (2000) Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge management, Academy of Management Executive, 14(4): 113-28.

Dia, M. (1996) Africa’s management in the 1990s and Beyond, Washington: World Bank.

Dimaggio, P.J. and Powell, W.W. (1983) The iron age revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organisational fields, in W.W. Powell and P.J. Dimaggio (Eds) The new institutionalism in organisational analysis, Chicago: University of Oxford Press.

Djelic, M.L. (1998) Exporting the American model, Oxford: University of Oxford Press.

Drucker, P. (1955) The practice of management, London: W. Heinemann.

Eccles, R.G. and Nohria, N. (1992) Beyond the hype: Rediscovering the essence of management, Harvard: Harvard Business School Press.

Falola, T. (2003) The power of African cultures, Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Fincham, R. and Roslender, R. (2004) Rethinking the dissemination of management fashion, Management Learning, 35(3): 321-336.

Forester, J. (1992) ‘Critical ethnography: on field work in an Habermasian way’, in M. Alvesson and H. Willmott (Eds) Critical management studies, London: Sage Publications, pp. 46-65.

Gillespie, R. (1991) Manufacturing knowledge: A history of the Hawthorne experiments, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Geertz, C. (1979) From the native’s point of view: on the nature of anthropological understanding, in P. Rabinow and W.M. Sullivan (Eds), Interpretive social science, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Glock-Grueneich, N. (2003) Eliciting compassion, framing truth and seeing what isn’t there, Proceedings LAP 2003, Tilburg.

Grant, D., Keenoy, T. and Oswick, C. (1998) Discourse and organisation, London: Sage Publications.

Grint, K. (1992) Fuzzy Management, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grint, K. and Case, P. (1998) The violent rhetoric of reengeneering: Management consultancy at the offensive, Journal of Management Studies, 35(5): 557-77.

Guillen, M.F. (1994) Models of management, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Habermas, J. (1984) The theory of communicative action, Vol. I 1984, Vol II 1987, Boston: Beacon.

Habermas, J. (1989) Bemerkungen zu J. Searle’s ‘Meaning, communication and representation’, in J. Habermas (Ed.) Nachmetaphysisches Denken, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Hacker, P.M.S. (1997) Wittgenstein’s place in twentieth century analytic philosophy, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Hardy, C., Lawrence, Th.B. and Phillips, N. (1998) Talk and action: Conversations and narrative

international Collaboration’, in D. Grant, T. Keenoy and C. Oswick (Eds) Discourse and organisation, London: Sage Publications.

Holman, D. and Thorpe, R. (2003) Management and language, London: Sage Publications.

Huczynski, A.A. (1993) Management gurus, London: Routledge.

Jackson, T. (2004) Management and change in Africa: A cross-cultural perspective, London: Routledge.

Karsten, L. and Illa, H. (2004), Ubuntu comme un concept de management, Cedres Etudes, special gestion.

Karsten, L. and Veen, K. van (1998) Management concepten in beweging: tussen feit en vluchtigheid, Assen: Van Gorcum.

Khoza, R. (1994), The need for an afrocentric approach to management, in P. Christie et al. (Eds), African Management, Randburg: Knowledge Resources (PTY) Ltd.

Kieser, A. (1997), Rhetoric and myth in management fashion, Organisation, 4(1).

Kieser, A. (2002) On communication barriers between management science, consultancies and business organisations, in T. Clarke and R. Fincham (Eds) Critical consulting, London: Blackwell.

Lascaris, R. and Lipkin, M. (1993) Revelling in the wild, Tafelberg: Human & Rousseau.

Lervik, J.E. and Lunnan, R. (2004) Contrasting perspectives on the diffusion of management knowledge, Management Learning, 35(3): 287-302.

Linell, P. (1998), Approaching dialogue talk, interaction and contexts in dialogical perspectives, Amsterdam: John Benjamin Publishing Company.

Locke, R.R. (1996) The collapse of the American management mystique, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Locke, R.R. and Schöne, K. (2004) The entrepreneurial shift, Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Managaliso, M. (2001) Building competitive advantage from ubuntu: Management lessons from South Africa, Academy of Management Executive, 15(3).

Mbigi, L. and Maree, J. (1995) Ubuntu: The spirit of African transformation management, Randburg: Knowledge Resources.

Micklethwait, J. and Wooldridge, A. (1996) The witchdoctors; what the management gurus are saying, why it matters and how to make sense of it, London: Heinemann.

Miller, R.C. (1992) Kairos in the rhetoric of science, in S.P. Witte et al. (Eds) A rhetoric of doing, Carbondale Southern: Illinois University Press.

Moldoveanu, M. (2002) Language, games and language games, The Journal of Socio-Economics, 31: 233-251.

Mphahlele, E. (2002), ES’KIA, Johannesburg: Kwala Books.

Nohria, N. and Eccles, R.G. (1998) Where does management knowledge come from?, in J.L. Alvarez (Ed.) The diffusion and consumption of business knowledge, New York: Oxford University Press.

Pascale, R. (1990) Managing on the edge, London: Penguin.

Purcell, J. (1987) Mapping management styles in employee relations, Journal of Management Studies, 24(5): 533-48.

Patricia, P. and Secheraga, A. (1998) Using the African philosophy of ubuntu to introduce diversity into the business school, Chinmaya Management Review, 2(2).

Ramose, M. (1999) African philosophy through ubuntu, Harare: Mond Books.

Reed, M. (1998) Organisational analysis as discourse analysis: A critique, in D. Grant, T. Keenoy and C. Oswick (Eds) Discourse and organisation, London: Sage Publications.

Rwelamila, P.D., Talukkaba, A.A. and Ngowi, A.B. (1999) Tracing the African project failure syndrome: The significance of ubuntu, Engineering, constructing and architectural management, 6(4): 335-46.

Samra-Fredericks, D. (2000) Doing board-in-action research – an ethnographic approach for the capture and. analysis of directors’ and senior managers’ interactive routines, Corporate Governance, 8(3): 244-57.

Samra-Fredericks, D. (2000) An analysis of the behavioural dynamics of corporate governance: A talk-based ethnography of a UK manufacturing board in action, Corporate Governance, 8(4): 311- 26.

Sanders, M. (1999) Reading lessons, Diacritics, 29(3).

Searle, J.R. (1969) Speech acts, an essay in the philosophy of language, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J.R. (2002) Consciousness and language, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shenhav, Y. (1999) Manufacturing rationality: The engineering foundations of the managerial revolution, Oxford: oxford University Press.

Shotter, J. and Curliffe, A.L. (2003), Managers as practical authors: Everyday conversations for action, in D. Holman and R. Thorpe (Eds) Management and language, London: Sage Publications.

Shutte, A. (1993) Philosophy for Africa, Milwaukee: Marquette University Press.

Skinner, Q. (2002) Visions of politics vol. 2: Renaissance virtues, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Silverman, D. (1998) Harvey Sacks: Social science and conversation analysis, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Smiddy, H.F. (1955) General Electric’s philosophy and approach for manager development, General Management Series (nr. 174), The American Management Association.

Smith, B. (2003) John Searle, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, Ch. (1995) Philosophical arguments, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Taylor, J.R. and Every, E.J. van (2000) The emergent organisation: Communication as its site and surface, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ten Bos, R. (2000) Fashion and utopia in management thinking, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Ten Have, S. Ten Have, W., Stevens, F. and Elst, M. van der (2003) Key management models, London: Prentice Hall.

Tsoukas, H. (1998) Forms of knowledge and forms of life in organised contexts, in R.C.H. Chia (Ed.) In the realm of organisation, London: Routledge.

Tsutsui, W.M. (1998) Manufacturing ideology: Scientific management in twentieth-century Japan, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Watson, R.P. (1997) Wittgenstein on language: Toward a theory (and the study) of language in organisations, Journal of Management History, 3(4): 360-74.

Watson, T. (1994) In search of management: Culture, chaos and control in managerial work, London: Routledge.

Wittgenstein, L. (1922) Tractatus logico-philosophicus (reprinted 1961), London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953) Philosophical investigations, Oxford: Blackwell.