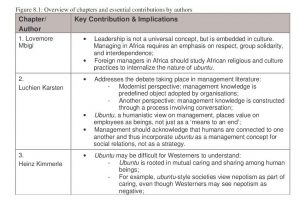

Hannah Arendt – Ills. Ingrid Bouws

Ideology and terror: The experiment in total domination

In chapter two of Hannah Arendt’s Response to the Crisis of her Time it was argued that Arendt’s typology of government rests on the twin criteria of organisational form and a corresponding ‘principle of action’. In the post-Origins essay On the Nature of Totalitarianism, Arendt argues that Western political thought has customarily distinguished between ‘lawful’ and ‘lawless’, or ‘constitutional’ and ‘tyrannical’ forms of government (Arendt 1954a: 340). Throughout Occidental history, lawless forms of government, such as tyranny, have been regarded as perverted by definition. Hence, if

… the essence of government is defined as lawfulness, and if it is understood that laws are the stabilizing forces in the public affairs of men (as indeed it always has been since Plato invoked Zeus, the god of the boundaries, in his Laws), then the problem of movement of the body politic and the actions of its citizens arises. (Arendt 1979: 466-7)

‘Lawfulness’ as a corollary of constitutional forms of government is a negative criterion inasmuch as it prescribes the limits to but cannot explain the motive force of human actions: ‘the greatness, but also the perplexity of laws in free societies is that they only tell what one should not, but never what one should do’ (ibid.: 467). Arendt, accordingly, lays great store by Montesquieu’s discovery of the ‘principle of action’ ruling the actions of both government and governed: ‘virtue’ in a republic, ‘honour’ in monarchy, and ‘fear’ in tyrannical forms of government (Arendt 1954a: 330; Arendt 1979: 467-8).

In all non-totalitarian systems of government, therefore, the principle of action is a guide to individual actions, although fear in tyranny is ‘precisely despair over the impossibility of action’ since tyranny destroys the public realm of politics and is therefore anti-political by definition. Nevertheless, the state of ‘isolation’ and ‘impotence’ experienced by the individual in tyrannical forms of government springs from the destruction of the public realm of politics whereas the mobilisation of the ‘overwhelming, combined power of all others against his own’ (Arendt 1954a: 337) does not eliminate entirely a minimum of human contact in the non-political spheres of social intercourse and private life. Thus, if the fear-guided actions of the subject of tyrannical rule are bereft of the capacity to establish relations of power between individuals acting and speaking together in a public realm of politics, the ‘isolation’ of the political subject does not entail the destruction of his social and private relations (ibid.: 344). Therefore, in all non-totalitarian forms of government, the body politic is in constant motion within set boundaries of a stable political order, although tyranny destroys the public space of political action (Arendt 1979: 467).

In all non-totalitarian systems of government, therefore, the principle of action is a guide to individual actions, although fear in tyranny is ‘precisely despair over the impossibility of action’ since tyranny destroys the public realm of politics and is therefore anti-political by definition. Nevertheless, the state of ‘isolation’ and ‘impotence’ experienced by the individual in tyrannical forms of government springs from the destruction of the public realm of politics whereas the mobilisation of the ‘overwhelming, combined power of all others against his own’ (Arendt 1954a: 337) does not eliminate entirely a minimum of human contact in the non-political spheres of social intercourse and private life. Thus, if the fear-guided actions of the subject of tyrannical rule are bereft of the capacity to establish relations of power between individuals acting and speaking together in a public realm of politics, the ‘isolation’ of the political subject does not entail the destruction of his social and private relations (ibid.: 344). Therefore, in all non-totalitarian forms of government, the body politic is in constant motion within set boundaries of a stable political order, although tyranny destroys the public space of political action (Arendt 1979: 467).

Arendt argues that totalitarianism is distinguished from all historical forms of government, including tyranny, insofar as it has no use for any ‘principle of action taken from the realm of human action’, since the essence of its body politic is ‘motion implemented by terror’ (Arendt 1954a: 348; see 331-3). In other words, totalitarianism aims to eradicate entirely the human capacity to act as such (Arendt 1979: 467). For totalitarian rule targets the total life-world of its subjects, which in turn presupposes a world totally conquered by a single totalitarian movement.[i] Hence, only in

… a perfect totalitarian government, where all men have become ‘One Man’, where all action aims at the acceleration of the movement of nature or history, where every single act is the execution of a death sentence which Nature or History has already pronounced, that is, under conditions where terror can be completely relied upon to keep the movement in constant motion, no principle of action separate from its essence would be needed at all. (ibid.)

This important passage contains several key ideas that need to be carefully unpacked. Firstly, we encounter Arendt’s conception of society reduced to ‘One Man’ or a single, undifferentiated Mankind as a condition of a ‘perfect totalitarian government’. We may note here that totalitarianism thus conceived constitutes the very antithesis of the political in Arendt’s sense of men acting and speaking together in a public realm of politics. Secondly, Arendt contends that only in such a perfect totalitarian system would terror, which she views as the ‘essence’ of totalitarianism, suffice to sustain totalitarian rule. Hence, in all imperfect totalitarian dictatorships, terror in its dual function as the ‘essence of government and principle, not of action, but of motion’ (ibid.), is an insufficient condition of totalitarian rule. For, insofar as totalitarianism has not completely eliminated all forms of spontaneous human action, freedom, or the inherent human capacity to ‘make a new beginning’, exists as an ever-present potential within society (ibid.: 466).[ii] Totalitarian movements must therefore strive to eliminate this capacity for political action, and any form of spontaneous human relations. Hence:

What totalitarian rule needs to guide the behaviour of its subjects is a preparation to fit each of them equally well for the role of executioner and the role of victim. This two-sided preparation, the substitute for a principle of action, is the ideology. (ibid.: 468)

However – and this is a crucial point – Arendt stresses that it is

… in the nature of ideological politics … that the real content of the ideology (the working class or the Germanic peoples), which originally had brought about the ‘idea’ (the struggle of classes as the law of history or the struggle of races as the law of nature), is devoured by the logic with which the ‘idea’ is carried out. (Arendt 1979: 472)

In other words, ‘the preparation of victims and executioners which totalitarianism requires in place of Montesquieu’s principle of action is not the ideology itself – racism or dialectical materialism – but its inherent logicality’ (ibid.: 472). In Arendt’s view, the device of ‘logicality’, which underpins all ideological thought processes, draws its strength from a simple human fact; ‘it springs from our fear of contradicting ourselves’ (ibid.: 473).

Arendt’s concept of totalitarian ideology is linked to her category of totalitarian ‘lawfulness’. She argues that totalitarian rule ‘explodes’ the opposition between lawful and lawless government, since although lawless in the conventional sense that it disregards even its own positive laws, unlike tyranny, it is ‘not arbitrary insofar as it obeys with strict logic and executes with precise compulsion the laws of History or Nature’ (Arendt 1954a: 339-40). This means, for one thing, that totalitarianism is not an exaggerated version of the arbitrary and self-interested rule of the tyrant and the laws of Nature or History are not the ‘immutable ius naturale’ or the ‘sempiternal customs and traditions of history’, from which positive laws governing the actions of men customarily derive their authority. In its totalitarian incarnation, ‘law’ no longer signifies the stabilising legal framework governing human actions, but instead transforms individuals into the living embodiments of the laws of movement, ‘either riding atop their triumphant car or crushed under its wheels’ (ibid.: 341). Since ‘totalitarian government is only insofar as it is kept in constant motion’ (ibid.: 344), the comparatively stable positive legal framework guiding the actions of ruler and ruled within the finite territorial realm of the modern nation-state is antithetical to the requirements of a totalitarian regime. Individual subjects of totalitarian rule either surrender to the dynamic process of becoming, or they are consumed by it: ‘”guilty” is he who stands in the path of terror, that is, who willingly or unwillingly hinders the movement of Nature or History’ (ibid.: 342). The qualification is significant, since the automatism of the impersonal and dynamic forces of Nature or History enjoy complete primacy over the individual members of society, who either join the movement or are swept away by it.

Ideology’s function

Totalitarian lawfulness applies the laws of Nature or History ‘directly to the “species”, to mankind [and] if properly executed, are expected to produce as their end a single “Mankind”’ (ibid.: 340). Ideology’s function is to transform Nature and History ‘from the firm soil supporting human life and action into supra-gigantic forces whose movements race through humanity’ (ibid.: 341). This function, rather than the substance of the ideology, distinguishes totalitarian ideologies from their antecedents in the nineteenth century. As we have seen, in the first two parts of Origins Arendt foregrounds the phenomena of race-thinking and class-thinking, both of which were general trends in nineteenth century European thought and politics, whereas only Marxism could lay claim to a respectable philosophical lineage. Race-thinking and racism, which interpret history as a natural contest of races, springs from the ‘subterranean’ currents – that is, the gutter – of European political thought (Arendt 1953f: 375). Still, both resonated with a substantial body of popular opinion and sentiment since both doctrines derived their potency and persuasive power from actual historical trends. For ‘persuasion is not possible without appeal to either experiences or desires, in other words to immediate political needs’ (Arendt 1979: 159).

The transition to the twentieth century coincided with the ascendancy of racism and Marxism and their emergence as the dominant ideologies in inter-war Europe, a dominance that was a function of their coincidence with the century’s two most important elements of political experience; namely, ‘the struggle between the races for world domination, and the struggle between the classes for political power’. Racism and communism triumphed over competing ideologies both because they reflected dominant currents in society and politics and because they were seized upon as the official ideologies of the most powerful and successful totalitarian movements (ibid.: 470). Their totalitarian character, moreover, presupposed emptying racism and revolutionary socialism of their ‘utilitarian content, the interests of a class or nation’ (ibid.: 348), generating a precedence of form and function over content, of infallible prediction over interest and explanation, driving ‘ideological implications into extremes of logical consistency’ (ibid.: 471).[iii] In this way, totalitarian ideologies manufactured a total explanation of reality freed of inconsistencies, unhampered by mere facts, and independent of all experience.

For Hitler, Arendt tells us, this process was set in motion by a ‘supreme gift for “ice cold reasoning”’, for Stalin, by the ‘mercilessness of his dialectics’ (ibid.); for both bespeaking a determination to effect controlled changes in human nature as the primary impediment to total domination. Total domination, in turn, guided by totalitarian ideology and actualised by the application of terror, invariably results ‘in the same “law” of elimination of individuals for the sake of the process or progress of the species’ (Arendt 1954a: 341). Nevertheless, whereas the application of terror is initially aimed at eliminating opposition, total terror also serves the important function of ‘stabilising’ men to permit the unhindered movement of Nature or History, eliminating ‘individuals for the sake of the species’ and sacrificing ‘men for the sake of mankind’ (ibid.: 343). Having discovered the laws of motion of totalitarian ideologies – that is, having mastered the intricacies of totalitarian organisation –, the dictator eliminates all obstacles to the fulfilment of the objective laws of movement. Unlike the tyrant, who, as a ‘free agent’, imposes his arbitrary subjective will, the totalitarian ruler acts in accordance with the logic inherent in the idea, freely submitting to his function as

… the executioner of laws higher than himself. The Hegelian definition of Freedom as insight into and conforming to ‘necessity’ has here found a new and terrifying realisation. For the imitation or interpretation of these laws, the totalitarian ruler feels that only one man is required and that all other persons, all other minds as well as wills, are strictly superfluous. (Arendt 1954a: 346)

In the popular attraction of totalitarian ideologies, which derives from their all-encompassing explanation of life and the world, secures the leader in his role as ‘the functionary of the masses he leads’ (Arendt 1979: 325). Once seized upon by totalitarian movements, notions of a classless society or a master race presuppose ‘dying classes’ and ‘unfit races’. The ‘monstrous logicality’ inherent in such ideological constructs dictates that whosoever accepts their initial premise but does not draw the logical conclusion of exterminating ‘class enemies’ or ‘inferior races’, is ‘plainly either stupid or a coward’ (ibid.: 471, 472). Still, without the Leader’s genuine gift for mobilising the masses and implementing the novel methods of totalitarian organisation, ideological intent could not be translated into historical reality. Thus, despite the fact that neither Hitler nor Stalin added anything of substance to the ideologies which they adopted, it is they who discovered the principle of logical process which ‘like a mighty tentacle seizes you on all sides as in a vise and from whose grip you are powerless to tear yourself away; you must either surrender or make up your mind to utter defeat’ (Stalin in ibid.: 472).

If Arendt regards neither class-thinking nor race-thinking as inherently totalitarian, this is because any ideology or system of ideas, insofar as it is articulated as a definite theoretical or political doctrine or formulated as a party program, is incompatible with totalitarianism. For doctrines and programs, like positive laws, set limits, establish boundaries, and introduce stability (ibid.: 159, 324, 325). Nevertheless, all ideologies have totalitarian ‘elements’, for every ideology adopts an ‘axiomatically accepted premise’ that forms the basis of a logically or dialectically constructed argument, whose absolute consistency is a function of its complete emancipation from all observable facts, contrary evidence or life experience (ibid.: 470, 471). This is a crucial aspect of Arendt’s argument, for she stresses that the ‘arrogant emancipation from reality and experience’ points to the nexus between ideology and terror characteristic of all totalitarian regimes, and accounting for their unprecedented destructive power. The key to unlocking this power resides in the totalitarian organisation of society. Freed of the customary standards of lawful action and verifiable truth claims, totalitarian movements unleash terror in accordance with the imperatives of the ideological reconfiguration of society. All members of society are now the potential targets of a regime of terror that functions independently of both the interests of society and its members (Arendt 1954a: 350).

Ideology and terror

Hannah Arendt Plaque in Marburg

The link thus established between ideology and terror, although only realised by totalitarian organisation, is nonetheless implicit in all forms of ideology, for ideology ‘is quite literally what its name indicates: it is the logic of an idea’ and it treats the course of history in all its contingency and complexity as a function of the ‘logical exposition of its “idea”’.[iv] The strict logicality with which an ideological argument is extrapolated from an axiological premise is termed ‘totalitarian lawfulness’ by Arendt. Thus the ‘ideas’ of race and class ‘never form the subject matter of the ideologies and the suffix –logy never indicates simply a body of “scientific” statements about something that is, but the unfolding of a process which is in constant change’ (Arendt 1979: 469) – the ‘idea’, that is, as instrumental in calculating the course of events. Ideology in this sense is a strictly closed system of thought since the vagaries and contingencies of history are presumed to be subject to an overarching, ‘consistent movement’ of history which can explain all contradictions and resolve all difficulties ‘in the manner of mere argumentation’ (ibid.: 470).

All ideologies therefore appeal to a putative ‘scientificality’ that purports to reveal the motor of history with the same precision and logical consistency to be found in the natural sciences. Arendt stresses, however, that the scientificality of ideological thinking is distinct from ‘“scientism” in politics [that] still presupposes that human welfare is its object, a concept that is utterly alien to totalitarianism’. Thus ‘modern utilitarianism’, whether socialist or positivist, is imbued with the interests of class or nation (ibid.: 347) and strives to either transform the outside world or bring about a ‘revolutionizing transmutation of society’. The evaluation of interest as an omnipresent force in history, together with the assumption that power is subject to discoverable objective laws, collectively constitute the core of utilitarian doctrines. Totalitarian ideologies, on the other hand, aim to transform human nature itself (ibid.: 458, also 440), since the human condition of plurality is the greatest obstacle standing in the way of the realisation of an ideologically consistent universe. For a view of history as a logical and consistent process of becoming, set in motion by a movement which is the expression of the ‘idea’ and which is unaffected by external forces, dispenses with the ‘freedom inherent in man’s capacity to think’ embracing, instead, the ‘straight jacket of logic’ (ibid.: 470). Thus, the ‘logicality of ideological thinking’ is both a template of an imagined society as well as the motor of a regime of terror, which is both means and end. Once seized upon by a totalitarian government, ideologies form the basis of all political action, not only guiding the actions of the government but also rendering these actions ‘tolerable to the ruled population’ (Arendt 1954a: 349). In this sense, ideology facilitates the extraction of ‘consent’ from the members of society whose standards of judgement are wholly informed by a closed system of thought and whose actions, or inaction, are judged solely by the requirements of the ‘objective laws of motion’.

The transformation of ideologies into fully fledged totalitarian ideologies is thus a crucial prerequisite of totalitarian rule. Anti-Semitism, for example, only becomes ideological in Arendt’s sense once it presumes to explain ‘the whole course of history as being secretly manoeuvred by the Jews’, rather than merely expressing a hatred of Jews. Similarly, socialism qua ideology ‘pretends that all history is a struggle of classes, that the proletariat is bound by eternal laws to win this struggle, that a classless society will then come about, and that the state, finally, will wither away’. By stripping away contingency and human agency as determinants of history, totalitarian ideologies point to irresistible forces that allegedly disclose the true course of events, past and future, ‘without further concurrence with actual experience’ (Arendt1954a: 349). Totalitarianism’s ‘supersense’ construes all factuality as fabricated, therewith eliminating the ground for distinguishing between truth and falsehood. Guided by ideology and goaded by terror, human beings lose their innately human capacity for spontaneity and action, which is to say their capacity for political discourse and the distinctly human capacity for creative and unconstrained thought (ibid.: 350).

Arendt argues that totalitarian rulers employ a deceptively simple device for transforming ideologies into coercive instruments: ‘they take them dead seriously’ (Arendt 1979: 471; Arendt 1954a: 350). This statement might seem self-evident, even trite. Yet Arendt means by this two very important points. Firstly, she contends that neither Hitler nor Stalin contributed anything of substance to racism and socialism respectively. Their importance as ideologists stems from their understanding the political utility of eliminating ideological complexity, by means of which they transform ideologies into ‘political weapons’. Conversely, the Leader’s image of ‘infallibility’, as propagated by the party, hinges on his pretence at being the mere agent of the ideological laws of Nature or History. The Leader reinforces this image by means of a simple but effective ruse, for it is customary for the Leader to reverse the relation of cause and effect by proclaiming political intent in the guise of a ‘prophecy’. Thus, for example, when Hitler in 1939 ‘prophesied’ that in the event of another world war the Jews of Europe would be ‘annihilated’, he was in fact announcing that there would be another world war and that the Jews would be annihilated. Thus, political intent concealed as ‘“prophecy” becomes a retrospective alibi’ (Arendt 1979: 349): the realisation of this ‘prophecy’ has the effect of reinforcing the Leader’s image of infallibility.[v] Similarly, when in 1930 Stalin identified ‘dying classes’ as the central threat to the consolidation of Bolshevik power, he was in fact merely identifying the targets of the coming purges. From this point of view the content of the ideology and its substance – the prophecies of ‘dying classes’ and ‘unfit races’ – are indeed of consequence insofar as they reveal the Leader’s political intentions by identifying the groups to be targeted by the regime’s terror. The ‘language of prophetic scientificality’ (ibid.: 350) also answers to the needs of disoriented and displaced masses, whose insecurity renders them susceptible to all-encompassing explanations of life and the world and whose membership of mass political movements releases them from the vagaries of an indeterminate fate (ibid.: 352, 368, 381).

Propaganda

Arendt wishes us to see that the totalitarian Leader’s ideological fervour has nothing to do with the fidelity of ideological discourse and everything to do with eliminating ideological complexity, which is antithetical to the organisational needs of the movement. Ideological complexity is also an obstacle to the effectiveness of propaganda, which is distinct from ideology and serves as a recruiting device (ibid.: 343). Propaganda creates conditions in which both the movement and society can be reordered into what Hitler termed a ‘living organisation’ (ibid.: 361). In the pre-power phase, propaganda holds the ‘real world’ at bay, whose complexity and contingency continuously threatens the integrity of the movement and the internal consistency of its ideological world-view. Propaganda thus shelters the movement qua proto-totalitarian society from a worldly reality (ibid.: 366), attracting masses already predisposed to discounting the evidence of their senses and who are thus susceptible to the ‘propaganda effect of infallibility’ (ibid.: 349). Once the movement has seized power, this ‘effect’ is amplified by the totalitarian reorganisation of society, at which point ideology ceases to be a matter of mere opinion or ‘debatable theory’ (ibid.: 362). Instead, the totalitarian movement organises the members of society into a race or class reality presided over by the ‘never-resting, dynamic will’ of the Leader, which is the ‘supreme law in all totalitarian regimes’ (ibid.: 365).

Propaganda is thus principally aimed at the non-totalitarian world. Its distinctively totalitarian character is expressed ‘much more frighteningly in the organisation of its followers than in the physical liquidation of its opponents’ (ibid.: 364). Propaganda thus serves the organisational interests of the movement while ideology facilitates the exercise of terror, which coincides with the reorganisation of society itself. Ideology and terror are thus the instruments of a revolutionary transformation of society, since ideology identifies the victims of terror, whereas terror realises the claim ‘that everything outside the movement is “dying”’ (ibid.: 381). Fabrication rather than followers is the key to the success of totalitarian rule. Indeed, a community of ‘believers’ implies an element of fidelity that hinders the Leader’s freedom of action. What is required is a complete absence of the ability to distinguish between fiction and reality (ibid.: 385). Henceforth, factuality and reality become a matter of mere opinion, whereas the truth of lies is affirmed by the actualisation of ideological goals. Hence, not ‘the passing successes of demagogy win the masses, but the visible reality and power of a “living organization”’ (ibid.: 361).[vi] ‘Prophecy’ realised is its own best guarantee.

Arendt’s distinction between ideologies of the nineteenth century and the totalitarian ideologies of the inter-war period remains one of the most controversial aspects of her theory of totalitarianism. Critics routinely deride Arendt’s alleged ‘equation’ of racism and communism, whereas I have argued that the distinct contents of these ideologies is both acknowledged by Arendt and irrelevant to her focus on the functions that they fulfil ‘in the apparatus of totalitarian domination’ (Arendt 1979: 470). The persistence of this criticism reflects the inability of her critics to break out of a deterministic frame of reference, which always already accounts for novelty as the ‘“product” of antecedent causes’ (Kateb 1984: 56).

Bernard Crick argues that descriptions of the formation of ideologies, the disintegration of the old systems, and ‘what then happens’ do not establish ‘inevitable connections between them’ (Crick 1979: 38). Many ideologies and political sects arising in the nineteenth century go unmentioned by Arendt. And if Arendt ‘gives all too few glimpses of the nonstarters and the ideologies of the salon and the gutter that got nowhere’, she is nonetheless, and

… quite properly, writing history backward: she selects what is relevant to understanding the mentality of the Nazis and of the Communists under Stalin, and she is not writing a general account of nineteenth-century extreme political sects. (Crick 2001: 99)

Eric Voegelin

In response to a comment by Eric Voegelin in his 1953 review of Origins, Arendt provided a clear and rare statement of her method. Voegelin had argued that the true division in the crisis of contemporary (post-war) politics is not between liberals and totalitarians but between the ‘religious and philosophical transcendentalists on the one side, and the liberal and totalitarian immanentist sectarians on the other side’ (Voegelin in Isaac 1992: 71). Arendt’s A Reply to Eric Voegelin is unambiguous: ‘Professor Voegelin seems to think that totalitarianism is only the other side of liberalism, positivism and pragmatism. But … liberals are clearly not totalitarians’ (Arendt 1953c: 405). Arendt goes on to suggest that Voegelin’s misreading is rooted in their different approaches. Where she proceeds from ‘facts and events’, Voegelin is guided by ‘intellectual affinities and influences’, a distinction perhaps blurred by Arendt’s real interest in philosophical implications and shifts in spiritual self-interpretation. Nonetheless, Arendt formulates her general approach to the phenomenon of totalitarianism in quite distinct terms as follows:

But this certainly does not mean that I described ‘a gradual revelation of the essence of totalitarianism from its inchoate forms in the eighteenth century to the fully developed’, because this essence, in my opinion, did not exist before it had come into being. I therefore talk only of ‘elements’, which eventually crystallize into totalitarianism, some of which are traceable to the eighteenth century, some perhaps even farther back … Under no circumstances would I call any of them totalitarian. (Arendt 1953c: 405-06)

Arendt views totalitarianism as sui generis. To her mind, the totalitarian phenomenon derives its great force from the ‘ridiculous supersense of its ideological superstition’ (Arendt 1979: 457) and ‘the event of totalitarian domination itself’ (Arendt 1953c: 405). It does not arise on the basis of a substantive ideological content nor is ‘total domination’ a variation of historical forms of tyranny and despotism.[vii]

The complexity of this point stems from Arendt’s view of totalitarian ideologies as ‘instruments of explanation’ (Arendt 1979: 469) whose logical deduction of the movement of history from a single premise does away with the need for a guiding principle of behaviour. Totalitarian ideologies are not a system of belief guiding the actions of their adherents but an instrument exploited by totalitarian movements in their drive to mobilise the masses. Klemperer portrays National Socialism in this sense as a manifestation of the ‘weariness of a generation. It wants to be free of the necessity of leading its own life’ (Klemperer 2000: 158). By answering to this need, totalitarian movements attract a following that constitutes the nucleus of a nation-wide reorganisation of society into three sub-categories of humanity, presided over by the leader – the elite formations, party members, and rank and file sympathisers. Whereas the elite formations typically evince a fanatical adherence to ideology, the mass following is characterised by malleability and gullibility (Arendt 1979: 367, 382-4). Arendt argues that the totalitarian system of rule presupposes a mass following disabused of ideals, convictions and mere opinions, since these are obstacles to the laws of motion governing the movement of history. For this reason, totalitarian education has never sought to instil convictions in the masses, but to eliminate the capacity to form any (ibid.: 468). It is also for this reason that Arendt stresses the novel organisational devices binding the various strata of the movement directly to its leader, and the role of terror as the substitute for a principle of action. The party membership is not expected to put much faith in the integrity of official public statements. Knowledge within the party of Hitler’s serial lies inspired trust in his leadership for the simple reason that Hitler repeatedly demonstrated his ability to manipulate his domestic audience and outwit his foreign adversaries. Without ‘the organizational division of the movement into elite formations, membership, and sympathizers, the lies of the Leader would not work’ (ibid.: 383).

The novel form of totalitarian organisation – it’s peculiar ‘shapelessness’ – derives from an ingenious and rather simple device that results in an immense administrative and structural complexity. Whereas the division between the leader, elite formations and masses is suggestive of authoritarian state structures, political authority in totalitarian regimes radiates outwards unmediated from the leader to the various levels of institutional and party structures. Thus, although Hitler delegated enormous powers to key ministers and party and state functionaries, these powers were contained within strictly defined areas of competence and were conditional upon Hitler’s continued favour. Moreover, whereas authoritarian regimes typically establish discrete institutional spheres of clearly circumscribed sovereign state authority, totalitarian rule is characterised by a multiplication of overlapping and conflicting party and state institutions that inhibit the formation of a stable, hierarchical chain of command. The concentration of power in Hitler’s Chancellery was therefore a function of Hitler’s sole authority to decide the outcome of conflict within and between competing party and state institutions, rather than of a centralisation of hierarchically ordered political power.

Power of command

Theoretically, this means that totalitarian regimes are resistant to conventional analytical frameworks, for al of these to some extent presuppose stabilising hierarchical structures of authority typical of military dictatorships, whose ‘absolute power of command from the top down and absolute obedience from the bottom up’ define these regimes as non-totalitarian:

A hierarchically organized chain of command means that the commander’s power is dependent on the whole hierarchic system in which he operates. Every hierarchy, no matter how authoritarian in its direction, and every chain of command, no matter how arbitrary or dictatorial the content of its orders, tends to stabilize and would have restricted the total power of the leader of a totalitarian movement. In the language of the Nazis, the never-resting, dynamic ‘will of the Führer’ – and not his orders, a phrase that might imply a fixed and circumscribed authority – becomes the ‘supreme law’ in a totalitarian state. (Arendt 1979: 364-5; see also Schmitt 1947: 431)

The distinction between totalitarianism and tyranny or military dictatorship tells us something of the radical novelty of the former. Arendt wishes us to see that totalitarianism is fundamentally incompatible with the modern Western state, in any of its different forms. For all state forms are distinguished by their hierarchical structure, which rests on a principle of authority that simultaneously stabilises institutions and informs the actions of its members. In other words, the subjects of all non-totalitarian states are guided by a ‘principle of action’ that in one form or the other establishes limits. Even the fear-guided actions of the subjects of tyranny possess an element of calculability and predictability, whereas totalitarian regimes eliminate all immutable standards and predictable limits. A regime of terror that prepares its subjects equally for the role of victim and of executioner cannot permit the stabilisation of political relations, nor can it afford any element of predictability, since in either case terror would cease to be total. For this reason, the Leader’s function is indispensable, since it

... is only from the position in which the totalitarian movement, thanks to its unique organization, places the leader – only from his functional importance for the movement – that the leader principle develops its totalitarian character. (Arendt 1979: 365; see also Schmitt 1947: 435)[viii].

Once the movement has seized power, the ‘absolute primacy of the movement’ over both state and nation is complemented by the unchallenged power of the Leader over the movement who, unlike the tyrant, discards ‘all limited and local interests – economic, national, human, military – in favour of a purely fictitious reality in some indefinite distant future’ (Arendt 1979: 412). To sustain both the dynamism and primacy of the movement, moreover, the Leader must ensure organisational ‘fluidity’, which is by definition antithetical to structure and stability (ibid.: 368).

All authoritarian regimes, whether or not they are dictatorships, necessarily imply hierarchy, stability, and some limitation of absolute power, since the principle of ‘law as command’ establishes relations of authority that in some form or other limit the actions of the government (ibid.: 405; see also Schmitt 1947: 437). Conversely, totalitarian regimes imply fluidity, absence of a clear chain of command, and a nihilistic principle of totalitarian ‘lawfulness’ that inhibits the stabilisation of any law, any institution, and any way of life. The totalitarian leader, moreover, is the only member of society who is not bound by his own decrees and edicts, or by legality of any kind. For this reason, Arendt argues that totalitarian societies can have no genuine state form, since the institution of the state is by definition a reified, legally bounded and finite entity. The state, moreover, serves to establish a distance between the ruling elite and the rest of the population. Totalitarianism collapses all distance, introducing a total identity between leader and masses that is actualised in its most concentrated form in the practice of organised acclamation.

March 1921 Lenin announced NEP

Given the ideological and organisational imperatives of the regime, ‘those who aspire to total domination must liquidate all spontaneity, such as mere existence of individuality will always engender, and track it down in its most private forms, regardless of how unpolitical and harmless these may seem’ (Arendt 1979: 456). Conviction and even mere opinion are manifestations of the capacity for critical thought and spontaneous action. The greatest threat to totalitarian rule, and the main target of total terror, is human spontaneity or ‘man’s power to begin something new out of his own resources, something that cannot be explained on the basis of reactions to environment and events’ (ibid.: 455). Total obedience, then, springs not from a conventional authoritarian notion of obedience but derives from the totally isolated and lonely subject’s ‘sense of having a place in this world only from [one’s] belonging to a movement’ (ibid.: 324). ‘Total loyalty’ – the psychological basis for total domination – can only be expected from completely isolated human beings and is ‘only possible when fidelity is emptied of all concrete content, from which changes of mind might naturally arise’ (ibid.). In this regard Hitler certainly enjoyed a decided advantage over Stalin who inherited the Bolshevik party program, a far more ‘troublesome burden than the 25 points of an amateur [Nazi] economist’ (ibid.). In this sense, Arendt regards the New Economic Policy (NEP) initiated by Lenin as an ‘obvious alternative[s] to Stalin’s seizure of power and transformation of the one-party dictatorship into total domination’ (Arendt 1967: xv-xvi, also vii, xi, xii, xiii, xv, xix, 390f). This has broader implications for Arendt’s interpretation of Marxist doctrine itself, which even in its Leninist guise is acknowledged as an obstruction to Stalin’s totalitarian ambitions. In this view,

… the ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist. (Arendt,1979: 474)

Arendt’s description of the reactive totalitarian subject establishes a basis for her view that both Marxism and Social Darwinism had to be subjected to ‘drastic oversimplification’ (Stanley 1994: 23) before they could be exploited for totalitarian purposes. Only in totalitarian regimes does ideology effect a total rupture between reality and fiction by transforming reality through the actions of the subjects, who are the carriers of the ‘idea’ as well as the vehicle for its realisation.

Arendt’s view that twentieth century totalitarian ideologies are irreducible to their nineteenth century antecedents also goes to the heart of the controversy about her novelty thesis – her view, that is, that mid-century totalitarian regimes were both organisationally and ideologically unprecedented. This view is more aggressively contested in regard to the Stalinist regime. Andrew Arato is highly critical of Arendt’s interpretation of Lenin’s revolutionary one-party dictatorship, rejecting her view of it as authoritarian or ‘pre-totalitarian’. While he agrees that there were options for non-totalitarian development at the point of Lenin’s death, he argues that Lenin’s political organisation had unmistakable totalitarian elements (Arato 2002: 474-9), a claim that Arendt does not dispute. Contrary to Arato’s view, Arendt does not gloss over those tendencies and policy measures in Lenin’s revolutionary dictatorship that presaged Stalin’s ‘Second Revolution’ of 1929. Nonetheless, she views Lenin’s NEP as a rational policy framework alternative to Stalin’s revolution ‘from above’ (Arendt 1979: xxxii, 319). Arato contests this, arguing that the NEP was both a necessary and a temporary intervention. Still, what interests Arendt is that Lenin was willing at all to place practical considerations above ideological commitments, when these seemed justified by circumstances. Whatever the merit of Arendt’s general analysis of Lenin’s dictatorship, her central point is that Lenin was not averse to the utility of rational calculation within the broader context of Bolshevik ideology. Arato himself concedes that there ‘were options for nontotalitarian developments at the moment of Lenin’s death’ (Arato,2002: 476), and he adjudges Bukharin’s strategy of an indefinite extension of the NEP as the basis of a real alternative to totalitarianism.

Conversely, Arendt’s contention that Lenin favoured inner-party democracy, albeit restricted to the working class, is problematic to say the least, for it was Lenin, after all, who disbanded the elected constituent assembly and combated pluralistic tendencies within the party.

Statesmanship

Nevertheless, Arato strains the spirit of Arendt’s analysis to match his reservations. Arendt, we are told, assures ‘us that the relevant actions were those of the great practical statesman (that is, a “Great Dictator”?) and not the Marxist ideologue’ (Arato 2002: 475). What Arendt actually argues is that ‘in these purely practical political matters Lenin followed his great instincts for statesmanship rather than his Marxist convictions’ (Arendt 1979: 319). Arendt does not equate statesmanship with dictatorship but points to Lenin’s undeniable leadership skills, nonetheless conceding that these were constantly being challenged by his dogmatic Marxist convictions. Arendt variously overstates and oversimplifies the content of Lenin’s political decisions, but she hardly endorses either Lenin’s dictatorship or his dictatorial tendencies, nor is she mistaken in her view that Lenin made important concessions to practical politics. These concessions may be of questionable historical significance, but then Arendt’s objective is to identify the totalitarian elements of the Leninist dictatorship; she was not engaged in writing a history of the revolution.

Arendt distinguishes between the Bolshevik movement, which in her view had definite totalitarian characteristics, and Lenin’s revolutionary dictatorship, which did not constitute ‘full totalitarian rule’ in her sense (ibid.: 318). The distinction might seem trite taken out of context, but then it is Arato who concedes that Arendt ‘is surprisingly aware of the variety of autocratic forms of rule’ (Arato 2002: 473), and approvingly cites her postulation of ‘a post-totalitarian dictatorship in the Soviet Union’ (ibid.: 474) following Stalin’s death in 1953. Arato is willing to accept Arendt’s notion of ‘detotalitarianisation’ but unwilling to countenance the possibility of a Leninist pre-totalitarian dictatorship. His reasoning is that

… the ‘conspiratorial party within the party’ to which Arendt ascribes the victory of Stalin, was in fact the party that Lenin invented and institutionalised after 1917 as the all-powerful agent of dictatorship. (ibid.: 477)

Yet surely Arato cannot be suggesting that the Soviet Communist Party of 1917, 1924, 1929 and 1938 were one and the same institution? Of course it was always ‘the all-powerful agent of dictatorship’, but of what kind of dictatorship? If Stalin simply inherited a ready-made totalitarian regime, what then possessed him to purge and exterminate practically the entire Bolshevik elite?[ix] Moreover, it is entirely wrong to suggest that Arendt apparently thought there were ‘totalitarian elements in Marx, but not Lenin’ (ibid.: 499n). Arendt certainly identified totalitarian ‘elements’ in Marx’s thinking, and Lenin was nothing if not Marxist, a fact accepted as axiomatic by Arendt. What she challenges is the assumption of a direct line of affinity between Lenin’s revolutionary thought and Stalin’s perversion of even his own ideas:

The fact that the most perfect education in Marxism and Leninism was no guide whatsoever for political behaviour – that, on the contrary, one could follow the party line only if one repeated each morning what Stalin had announced the night before – naturally resulted in the same state of mind, the same concentrated obedience, undivided by any attempt to understand what one was doing, that Himmler’s ingenious watchword for his SS-men expressed: ‘My honour is my loyalty’. (Arendt 1979: 324)

In short, Arendt stresses Stalin’s instrumentalist totalitarian logic that had as little to do with Marxism as Hitler’s Volksgemeinschaft had to do with brotherly love.

Allusions to Social Darwinism as a precursor of Nazism can be quite as misleading as portraying Stalin as an authentic Marxist-Leninist, although in one important sense – man as the accidental product of natural development – Darwinism prefigures the Nazi penchant for irresistible natural laws. Darwin’s evolutionary theory, however, is in principle a theory of chaos, of chance. It describes a natural process characterised by an overwhelming tendency to fail; a becoming that is as much a product of that failure as it is of opportunity. One could liken the totalitarian ideologies themselves to the chance ‘successes’ of nature, emerging from a melange of genetic variants to become fully formed entities dominating the intellectual landscape of history, as have many species dominated their natural environments. Opportunity, genetic predisposition, circumstance; together these produce a chance crystallisation of a new political reality that however forever holds within itself the potential of decline and catastrophe. The allusion to the catastrophic events of nature that brought about the extinction of the dinosaurs, throwing open the field of opportunity for other species to develop, is analogous of the historical catastrophe preceding the totalitarian movements. Indeed, it would not be stretching the bounds of credulity to portray the First World War as the historical equivalent of an asteroid striking earth, signalling the extinction of nineteenth century Europe and casting a pall over the familiar social and intellectual currents of European culture. Out of this disaster certain ideologies rose to prominence, but not without the catalyst of human agency. Human agency is thus also central to the historical process, and the Bolshevik Revolution is only the most notable and apparent instance of such agency in the twentieth century. The Darwinist metaphor might therefore elucidate Arendt’s interpretation of the constellation of ideologies vying for dominance during the late nineteenth century in historical circumstances that were as yet unfavourable to a final outcome. Bolshevism was already a fully formed contender prior to the First World War, whereas the elements of National Socialist ideology were condensed in the aftermath of Europe’s orgy of violence.

Arendt does not indulge in speculation about whether or not the Bolshevik revolution was foredoomed, given the impact of war, the violence of the revolution, and the brutal civil war that followed. But she does argue that the revolution could have taken a different course (see e.g. ibid.: 319). Similarly, whilst acknowledging the odds against a successful republican experiment in Weimar Germany, Arendt argues that National Socialism need not have triumphed in 1933. Nonetheless, once these movements had emerged victorious, the ground for autonomous human agency was eliminated by ‘stabilising’ men ‘in order to prevent any unforeseen, free, or spontaneous acts that might hinder freely racing terror’ (Arendt 1954a: 342). Law, understood as positive laws stabilising and delimiting a public-political realm of spontaneous human action governed by predictable moral, ethical, and legal standards, was now viewed as an obstacle to totalitarian ‘lawfulness’. The ‘law of movement itself, Nature or History, singles out the foes of mankind and no free action of mere men is permitted to interfere with it. Guilt and innocence become meaningless categories; ‘“guilty” is he who stands in the path of terror’ (ibid.). Indeed, there have been no instances of the enduring free action of men in the modern era outside of a public political realm governed by positive laws and guaranteed by the institutions of a sovereign territorial state. With all its impersonal power structures, the state was a final hurdle to be overcome en route to totalitarian rule.

Civil society

I have already drawn the reader’s attention to Arendt’s analysis of the novel strategy of the inter-war totalitarian movements, which by posing an extra-constitutional and extra-legal challenge to sovereign state authority prised open the most vulnerable aspect of the bourgeoisie’s formidable armour. The perceptiveness of Arendt’s analysis of the inter-war period is nothing short of prescient, once she turns this insight into an explanation of the vulnerability, in turn, of post-totalitarian dictatorships to a resurgent ‘civil society’. Although Arendt never uses the latter term, she clearly perceives the vulnerability of the post-Stalin dictatorships to the inverse strategy of undermining dictatorial authority by way of the popular reassertion of autonomous civic action, which constitutes the discursive basis of a reconstituted public realm. Whereas once the totalitarian movements had undermined the state by mobilising and organising mass social movements, the reified remnants of once dynamic totalitarian regimes are vulnerable to eruptions of spontaneous political action. Arendt, to be sure, regarded such political action as virtually impossible in full-blown totalitarian dictatorships. However, once a totalitarian regime undergoes a process of ‘stabilisation’, such as occurred in the post-Stalin era, the ground or ‘space’ for a reconstituted public realm re-emerges. All true totalitarian dictators guard against this development. Conversely, authoritarian dictators preside over institutionalised regimes of hierarchical power structures, which are by their very nature vulnerable to ‘extra-authoritarian’, popular interventions such as we witnessed in Poland in the early 1980s and throughout Eastern Europe in 1989. Post-totalitarian dictatorships, deprived of their former dynamism, can only react to concerted political challenges.

There was nonetheless an important difference between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that should be noted here. For whereas the pre-Nazi bourgeois nation-state was re-established in the wake of Hitler’s defeat, pre-Soviet Russia had never made the transition to bourgeois rule; that is, ‘the Russian despotism never developed into a rational state in the Western sense but remained fluid, anarchic, and unorganized’ (Arendt 1979: 247). Hence, the longevity of post-totalitarian (i.e. post-Stalin) Soviet rule owed as much to the absence of any alternative tradition of state power as it did to the hegemony of the Communist Party. Germany reverted to its pre-Nazi statism with relative ease whereas

… in Russia the change was not back to anything we would call normal but a return to despotism; and here we should not forget that a change from total domination with its millions of entirely innocent victims to a tyrannical regime which persecutes only its opposition can perhaps best be understood as something which is normal in the framework of Russian history. (Arendt 1975: 265-6)

The revolutionary upheavals of inter-war Europe were characterised by a wholly new brand of voluntarism and leadership that culminated in the formation of a range of autocratic and dictatorial regimes identified with the person of the dictator. In Hitler’s case, as Joachim Fest observed in 1973, what happened is ‘inconceivable without him, in every respect and in every detail. Any definition of National Socialism (or the system of government based upon it) that omits the name of Hitler misses the heart of the matter’ (Fest 1973: 19). This view is echoed by Raymond Aron, who argues that what happened in Germany is incomprehensible if we ‘omit the personal equation of the Führer and his combination of genius and paranoia’ (Aron 1980: 39). No doubt the same is true of Stalin, although as we shall see, historians are profoundly divided on this question. Whether we focus on the 1930s, Hitler’s glory years and Stalin’s nightmare of terror, or the war years during which Hitler’s mania of destruction was halted by wave upon wave of Soviet canon fodder, the personal imprint of the two dictators is unmistakable. But to say so merely elucidates a single dimension of a more complex reality. For equally important is the organisational dimension of the totalitarian system of rule that embraces a community of men who have become ‘equally superfluous’ (Arendt 1979: 457) and an ideological regime of terror that aims totally to eliminate the web of human relations.

The same case can be made for Stalin and in a somewhat qualified sense also for Mussolini. And indeed the case needs to be made. For to receive these historical figures as somehow preordained and hence irresistible entails surrendering to their logic, a fatalistic mind-set quite prevalent amongst exiled intellectuals of the inter-war years. Bertolt Brecht, for example, bitterly scorned Hitler’s barbaric regime, yet went to extraordinary lengths to justify in his own mind what was happening in Stalin’s utopia. Martin Esslin notes that in a man of Brecht’s high intelligence, this exercise in rationalisation amounted to ‘a kind of mental suicide, a sacrificium intellectus; and his letters show that he was only too well aware of it’ (Esslin 1982: 13). Conversely, the personality type of Hitler ‘teaches us something which, until his appearance, was unknown to history on this level: that utter individual nullity or mediocrity may be combined in one man with exceptional political virtuosity’ (Fest 1973: 20). Hitler played the political field with unparalleled skill, alone deciding on the nature and duration of tactical alliances, his thought and actions in this regard relatively free of preconceptions, at least during the pre-war period. In short, ‘he was no-one’s tool’. Still, Fest’s view that Hitler ‘coolly subordinated everything – people, ideas, forces, opponents, principles – to the goal that was the obsession of his life: the primitive accumulation of personal power’ (ibid.), seriously underplays the role of ideology in Hitler’s political universe. Hitler undoubtedly relished power, and certainly had no use for the trappings and amusements that preoccupied many of his satraps. Stalin, by contrast, could count on and exploit an existing system of power accumulation whilst contending with far greater forces of resistance, and far more difficult and unstable circumstances. ‘Class-thinking’ was nonetheless an altogether more respectable preoccupation of both the European masses and the intelligentsia than ‘race-thinking’ ever was. Hence, what Stalin lacked in the way of a socially cohesive and highly organised system of consensual complicity, he was able to make up for by ideological fiat and unfettered domestic terror. Yet Stalin, too, had to make a transition, transforming Marxist-Leninist doctrine into a deductive principle of action underpinning his totalitarian system of government.

The complex interplay of personal qualities and historical circumstances that determined the outcome of the revolutions-from-above carried out by Hitler and Stalin will be examined in greater detail in chapter five. In this section I have stressed the impact of World War One and revolution, which generated what Zeev Sternhell describes as a ‘break-away’; cataclysmic events ‘so disruptive as to take on the dimensions of a crisis in civilization itself’ (Sternhell 1979: 333). Pre-war ‘mob’ elements or militant residues of decaying classes – ‘the refuse of all classes’ (Arendt 1979: 155) – deprived of political representation and scornful of a society from which they were excluded, already dominated the political landscape of many European societies prior to the Great War (ibid.: 107, 108). More controversially, Arendt distinguishes between these mob elements, borne of nineteenth century street politics and the social dislocations produced by industrialisation, and twentieth century ‘masses’ springing from a disintegrating class society (ibid.: 326). With both common interest and ‘specific class articulateness’ (ibid.: 311) rendered ineffective as a basis for party or class political action, Continental Europe’s pre-war bourgeois hegemony, and its mood of generalised complacency, gave way to ‘anarchic despair’ (ibid.: 327), propelling rootless and ‘isolated’ masses into the organisational structures of totalitarian movements.

Isolation

Volksgemeinschaft

Arendt defines ‘isolation’ in this sense as a pre-totalitarian condition, in which the human capacities for action and power are frustrated by the destruction of political life characteristic of tyrannies (ibid.: 474). ‘Loneliness’, on the other hand, is a consequence of totalitarian rule, which destroys the individual’s capacities for thought and experience (ibid.: 475). A state of loneliness coupled to a growing individual sense of ‘uprootedness’ and ‘superfluousness’ liberated these masses from their social attachments and class identities (ibid.: 311). In the case of Germany, Hitler was able to exploit a peculiar mix of pathos and hope engendered by the devastation of the Great War. Germany’s defeat was a defeat for continuity, and Hitler spoke to a hope for a new beginning that a disastrous series of inter-war setbacks had frustrated but not quashed; a new beginning, moreover, that also entailed a yearning for the restoration of certain ‘traditional’ values. Hitler’s genius, if that is what it was, lay in his ability to speak to this paradoxical public mood, at once promising a future devoid of class and party political divisions and their replacement by an ideal Volksgemeinschaft which, however, entailed the no less divisive ideal of racial purity. If the commitment to a classless and party-less society was to prove little more than a ‘theatrical concession to the desires of violently discontented masses’ (ibid.: 263), given the already disastrous state of parliamentary politics and the social devastation wrought by mass unemployment, the commitment to the idea of race was to prove anything but flighty.

As I have argued in this essay, Arendt’s concept of totalitarian ideology as an instrument of terror rather than of persuasion gains fuller expression in conjunction with her discussion of the role of propaganda in constructing totalitarian rule. For Arendt the distinction between totalitarian ideology qua prosaic amalgam of borrowed elements, and totalitarian propaganda, the bearer of its fictional narrative, is primarily functional. The utility and intensity of propaganda is largely dictated by the nature of the threat posed by the non-totalitarian world to totalitarian regimes, and therefore serves the totalitarian dictator in his dealings with the outside world, although it plays an important role in overcoming such obstacles as freedom of speech and of association under conditions of constitutional government (ibid.: 341-4). Alternately, ideological indoctrination, invariably combined with terror, is directed inwardly at the initiated and ‘increases with the strength of the movements or totalitarian governments’ isolation and security from outside interference’ (ibid.: 344; emphasis added; see Arendt 1953a: 297-99). For Arendt, the real horror of the totalitarian application of terror, and by implication of totalitarian ideology, is that it not only continues to reign over populations whose subjugation has become absolute, but in fact intensifies over time. Whereas Miliband has argued that Stalinist terror operated in anticipation of opposition, constantly striking ‘at people who were perfectly willing to conform, on the suspicion that they might eventually cease to be willing’ (Miliband 1988: 145), for Arendt totalitarian terror was the function of the ‘idea’, its rationale.

Propaganda disappears entirely whenever the rule of terror has eliminated a sense for reality and factuality, and the ‘utilitarian expectations of common sense’ (Arendt 1979: 457). Together, ideology and propaganda, terror and fiction, weave elements of reality, of ‘verifiable experiences’, into generalised suprasensible worlds ‘fit to compete with the real one, whose main handicap is that it is not logical, consistent, and organized’ (ibid.: 362). In practice, this entails transforming movements into embodiments of ideology, ‘charged with the idea’, whether of race or of class. In other words, ideology is applied as an organisational principle to produce what Hitler aptly describes as a ‘living organization’ (Hitler in ibid.). The counterpart of the living organisation is the ‘special laboratory’ (ibid.: 392, 437, 458), the arena for the totalitarian experiment in total domination. Understood in these terms, the concentration camp is the ‘true central institution of totalitarian organizational power’ (ibid.: 438, also 456) in which propaganda has become as superfluous as humanity itself, and the extermination camp the monument to the totalitarian regime’s ideological consistency.

Towards the close of the war, mounting evidence of the existence and practices of the dedicated German extermination centres became a central preoccupation of Arendt’s writing. In 1945, she noted that ‘neither in ancient nor medieval nor modern history, did destruction become a well-formulated programme or its execution a highly organized, bureaucratized, and systematized process’ (Arendt 1945a: 109). Intimations of Arendt’s novelty thesis are already quite apparent, as is her view that the destructiveness of the Nazi regime cannot be comprehended merely as a continuation or direct consequence of the nihilism undoubtedly unleashed by the First World War. If the extraordinary and senseless destructiveness of the First World War provided the breeding ground for totalitarian movements, their ideologies manifested themselves as an ‘intoxication of destruction as an actual experience, dreaming the stupid dream of producing the void’ (ibid.: 110). The regulated death rate of the extermination camps was complemented by the organised torture of the concentration camps, whose purpose was ‘not so much to inflict death as to put the victim in a permanent status of dying’ (Arendt 1950a: 238). The interweaving of the human experience of death and a death-like existence in the extermination and concentration camps respectively were to Arendt’s mind a corollary of the totalitarian organisation of society.

Arendt’s sense of the ‘continuity’ of experience between life in totalitarian societies and death – or a death-like existence – in the camps, has been little discussed in the relevant literature. Commentators instead generally focus on the distinct dynamics of terror in German and Soviet society, pointing to the absence of dedicated extermination facilities in the Soviet Union and to a more pervasive regime of terror during the Stalin years. Michael Halberstam, for example, takes Arendt to task for seemingly disregarding the fact that ethnic Germans were not subjected to the level of terror that the constant threat of deportation visited upon even high party officials in the Soviet Union during the 1930s (Halberstam 2001: 106). Arendt was aware of this[x], explicitly arguing that the pre-war Nazi regime was not properly totalitarian and that it was only with Kristallnacht in 1938 and the outbreak of war that Hitler’s terror machine came into its own. Whereas terror reached its height in Germany with the long series of post-1941 military defeats, terror in the Soviet Union abated with the onset of war, only to resume with military victory, followed by the mass deportation of returning Soviet POWs (see e.g. Arendt 1979: xxv). It is the nature of total terror that concerns Arendt, a distinctive logic of total domination that aims to transform all of society, and

… to organize the infinite plurality and differentiation of human beings as if all of humanity were just one individual … The problem is to fabricate something that does not exist, namely, a kind of human species resembling other animal species… Totalitarian domination attempts to achieve this goal both through ideological indoctrination of the elite formations and through absolute terror in the camps. (ibid.: 438)

Ideological indoctrination pervades all of society in an attempt to lay hold of the general population, but the experiment in indoctrination is complemented by the concentration camp regime, the existence of which is public knowledge. It is this knowledge that makes terror a palpable daily reality of the general populace.

Total domination

Despite their ‘cynically admitted anti-utility’, the camps are the key to sustaining totalitarian rule, for the camp system infuses society with an ‘undefined fear’ that is essential both to maintaining the totalitarian movement’s hold over the populace and to inspiring ‘its nuclear troops with fanaticism’. The camps also perform the important function of initiating the regime’s elite cadres into the techniques of ‘total domination’, which would not be possible outside of this context, at least and until total domination had been established over all members of society. Without the camps, ‘the dominating and the dominated would only too quickly sink back into the “old bourgeois routine”’ (ibid.: 456). The camp phenomenon is thus central to Arendt’s understanding of totalitarianism, for the camp system constitutes the arena in which the innate logic of totalitarian rule reveals itself and in which the experiment in denaturing human beings is conducted. The ‘society of the dying established in the camps is the only form of society in which it is possible to dominate man entirely’. It would be a considerable understatement to describe as controversial Arendt’s rejection of the notion that ‘there was such a thing as one human nature established for all time’ as a ‘tragic fallacy’ (ibid.: 456). A clue to this statement, as indeed to the integral relation between Arendt’s theory of totalitarianism and her post-Origins theory of politics, is contained in a 1953 essay in which Arendt argues that ‘the success of totalitarianism is identical with a much more radical liquidation of freedom as a political and as a human reality than anything we have ever witnessed before’ (Arendt 1953c: 408). In the following section I would like to trace the contours of this ‘liquidation of freedom’ as it unfolds in Arendt’s account of the threefold stages of the totalitarian assault on human individuality.

‘To dream the stupid dream of producing the void’: Denaturing the human individual

Stalin Gulag Memorial

Man, this flexible being, who submits himself in society to the thoughts and impressions of his fellow-men, is equally capable of knowing his own nature when it is shown to him and of losing it to the point where he has no realisation that he is robbed of it. (Montesquieu)

‘Terror’ is not a generic term of reference in Arendt’s political thought. In a 1953 address published as

Mankind and Terror

, Arendt distinguishes between the principal forms of terror in Western political history. She argues that all forms of pre-totalitarian terror associated with tyranny, despotism, dictatorship, revolutionary and counter-revolutionary movements, plebiscitary democracy and modern one-party states, have a clearly circumscribed goal, target genuine opponents and generally cease once the regime’s objectives have been attained. Thus, for example, tyrannical forms of terror eliminate opposition as well as destroying the public realm of politics whereas the chief goal of revolutionary terror is to establish a new ‘code of laws’ (Arendt 1953a: 298). Totalitarian terror, on the other hand, commences once the regime has eliminated all its real enemies and is therefore apparently ‘counter to the perpetrator’s real [utilitarian] interests’ (ibid.: 302-03)[xi].

Thus the proposition that Stalin’s terror regime was a manifestation of revolutionary violence belies the fact that by the late 1920s all active resistance to the new Soviet regime had been eliminated. Henceforth, terror no longer served ‘the utilitarian motives and self-interest of the rulers’ (Arendt 1979: 440). Nor does the relative scale of terror necessarily reveal its nature and purpose. Moreover, distinctions such as that between Stalin’s ‘labour camps’ and Hitler’s concentration camps tend to be misleading insofar as the language of terror – its formal designations – typically conceals more than it reveals of the functioning of the terror apparatus. In this regard Arendt cautions against liberal rationalisations about ‘fear’ and ‘submission’ (Arendt 1953a: 300)[xii], for total terror targets ‘objective’ categories of victim without reference to the individuation presupposed by the logic of crime and punishment. The most important characteristic of totalitarian terror, however, is that it functions independently from such positive laws as may exist, and is unleashed only once all active and genuine opponents have been eliminated.

Moreover, the totalitarian regime of ideology and terror does not presuppose a state of total compliance for the simple reason that compliance presupposes norms whereas ‘totalitarian regimes establish a functioning world of no-sense’ emptied of ‘[c]ommon sense trained in utilitarian thinking’ (Arendt 1979: 458). But this can hardly be a description of the broader society in either Nazi Germany or Stalin’s Russia. Arendt argues that these societies only very imperfectly resemble their most characteristic institutions, the concentration camps, whose experiment in total domination generates an ‘enforced oblivion’ of the social subject, a strategy that ‘is preceded by the historically and politically intelligible preparation of living corpses’ (ibid.: 447). The various stages in the destruction of the individuality of the totalitarian subject begin in society and are completed in the artificial environment of the camp system, which reduces the inmates to ‘bundles of reactions’ (ibid.: 441). Although the broader society in totalitarian regimes is infused with a distinctive totalitarian logic, there are limits to the application of totalitarianism’s ideological ‘supersense’, for as long as society has not been totally subjected to ‘global control’ (ibid.: 459).

What is true of the general populace of totalitarian societies thus scarcely hints at the wholly fabricated environment of the camps, the locus of the experiment in total domination. Arendt identifies three stages marking the journey into hell of the victims of total terror. The first stage entails the organised destruction of the ‘juridical person in man’ by removing objective categories of people from the purview of the law and establishing the concentration camp system as an extra-judicial penal system. The objective innocence of the latter’s inmates, and the extra-legal status of its institutional existence, place the concentration camp system as a whole outside the realm of rational juridical calculation, and in a universe wholly different from a rights-based utilitarian regime (ibid.: 447-51). The death of the juridical person, ‘of the person qua subject of rights’ (Benhabib 1996: 65), is pre-figured by the nineteenth century experience of imperialism which, as we have seen, pitted the institutions of the imperialist nation-state against the fragile belief, on the part of the imperialist nations, in the universal rights of man. Arendt argues that the Rights of Man were never ‘philosophically established’ or ‘politically secured’ and hence were inherently vulnerable to historical developments (Arendt 1979: 447). The decline of the nation-state and the corruption of the supposedly inalienable Rights of Man, concomitant with nation-state imperialism, were amplified by the experience of the First World War, which exposed the fatal nexus between Europe’s high revolutionary ideals and her naked political ambitions. Total war had generated refugees on an unprecedented scale and the post-war Minority Treaties merely formalised the ‘denationalisation’ of millions of displaced persons, effectively placing them outside of Europe’s supposedly rights-based legal and political order (ibid.). The totalitarian experiment in the disenfranchisement and destruction of the juridical person marked the passage from the corruption of the Rights of Man to the systematic elimination of the juridical subject in man. This occurs when even a ‘voluntarily co-ordinated’ population – a population that cedes its political rights under extremes of terror – is deprived of its civil rights, becoming ‘just as outlawed in their own country as the stateless and homeless’ (ibid.: 451).

Totalitarian rule thus targets both ‘free opposition’ and ‘free consent’, since individual autonomy of any sort undermines the principle of total terror that arbitrarily selects objective categories of victim, destroying the stability and predictability that is incompatible with a system of rule predicated on perpetual motion. The device of ‘arbitrary arrest’ eliminates the capacity for free consent, ‘just as torture … destroys the possibility of opposition’ (ibid.). In this context Arendt makes a threefold distinction between the initial phase of totalitarian terror, the subsequent targeting of ‘objective categories’ of victims, and, finally, the more generalised state of terror that takes hold of all of society at the height of totalitarian rule. Whereas totalitarian rulers initially target opponents and those construed as asocial elements – the ‘amalgam of politicals and criminals’ (ibid.: 449) – this is followed by categories of enemy, such as homosexuals, Jews, and class enemies, whose most outstanding trait is complete innocence. Thus ‘deprived of the protective distinction that comes of their having done something wrong, they are utterly exposed to the arbitrary’ (ibid.)[xiii]. On the other hand, the general populace is often indifferent to the fate of the victims, since the former are usually still beholden to the utilitarian notion (or alibi) that in order to be ‘punished’, one must necessarily have ‘done something’.

Therefore, ethnic Aryans could still take some comfort from the fact that they were Judenrein, heterosexuals that they were not ‘perverted’, the proletariat that they were not ‘counter-revolutionaries’ – rationalisations that become quite impossible once total terror lays hold of the broader society. Arendt stresses that in the case of Germany, total terror became anything like a generalised condition only at the height of the war and Nazism’s most terroristic phase, from 1942 to 1944[xiv].

… [a]ny, even the most tyrannical, restriction of this arbitrary persecution to certain opinions of a religious or political nature, to certain modes of intellectual or erotic social behaviour, to certain freshly invented ‘crimes’, would render the camps superfluous, because in the long run no attitude and no opinion can withstand the threat of so much horror; and above all it would make for a new system of justice, which, given any stability at all, could not fail to produce a new juridical person in man, that would elude the totalitarian domination. (Arendt 1979: 451)

Thus ‘[w]hile the classification of inmates by categories is only a tactical, organizational measure, the arbitrary selection of victims indicates the essential principle of the institution’ (ibid.: 450). ‘Arbitrary’ in this context, it is again stressed, does not mean that the Nazis did not target determinate or general categories of victim, but instead that these categories were constantly expanded in ways that eliminated rational calculation as the basis for the actions of the populace. Even anti-Jewish measures were initially restricted to certain categories of Jew. At the height of total terror, moreover, the regime begins to apply the organisational principles of the camp system to society as a whole, when even those people indispensable to the functioning of the regime are consumed by the terror.

Living corpses

A second phase in the preparation of ‘living corpses’ targets the moral person in man. This entails the ‘creation of conditions under which conscience ceases to be adequate and to do good becomes utterly impossible’, since ‘organised complicity’ is constantly extended to include the broader society and the victims themselves (ibid.: 452). In its most extreme form, total terror coerces the participation of the concentration and death camp inmates in the extermination process itself. This is intended to destroy the capacity of the victims to form moral judgements. Thus, for example, a mother confronted by the ‘choice’ of which child immediately to send to the gas chamber is condemned not only to select death for the one, but also to internalise the principle of terror that always already dictates the ultimate death of the other. Her powerlessness to influence the ultimate outcome for either of her offspring means that the temporary reprieve for the surviving child is the source of an infinite torment that ceases only with the completion of the family murder. Under circumstances in which the distinction between persecutor and persecuted, killer and victim, is systematically undermined, the process of killing itself assumes the mantle of unreality corresponding to the existence of ‘living corpses’[xv].