How To Explain Hare Hunting To A Dead German Artist

Joseph Sassoon Semah, My Beloved Country – That Did Not Love Me, rug and black oil paint, 100X70 cm, 1977 Photography: Ilya Rabinovich – Courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semah

Joseph Sassoon Semah, a Baghdad-born artist who now lives and works in Amsterdam, is about to embark on an extensive multi-site project, in Amsterdam, Jerusalem, and Baghdad. Berlin-based poet and author Mati Shemoelof talks with him about his years living as an artist in Israel versus being a Babylonian Jew and an artist in Europe. They discuss Judaism, diaspora, exclusion, and acts of concealment and building.

The artist Joseph Sassoon Semah has never before given an interview to an art publication in Israel. The Israeli art world has not adequately recognized his work. Although he showed in several important institutions in Israel and worked with key curators, it was negligible compared with the scope of his oeuvre, especially following his move from Israel to Europe. What would have happened had he stayed in Israel? Was he stumped by his diasporic state or was he ahead of his time in dealing with the Jewish component of his art? It is not merely an objective issue to be measured by the number of exhibitions, but rather the artist’s subjective sense of his position in the art field. I gather from Semah that he has remained on the outside, beyond the walls of Jerusalem. In Europe, too, and especially in the Netherlands, his work is not widely known yet. This interview stems from my own interest in Semah’s identity (we are both of a Jewish Iraqi descent) and his work, but also as an intra-European process of an artistic, inter-generational analysis attempting to formulate the role of Jewish culture in Europe.

Semah was born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1948. His grandfather, Hacham Sassoon Kadoorie, was the chief rabbi of Baghdad’s Jewish community until his passing in 1971, even after they had all emigrated. In 1950, Semah and his family were uprooted from Iraq, and they moved to Israel. He grew up in Tel Aviv. Traumatized by his military service in the 1967 and 1973 wars, he chose exile and has been living in the Netherlands since 1981. The grandfather’s continued residence in Baghdad, along with some 20,000 more Jews, brings to mind Semah’s own position in Amsterdam (his grandfather did not immigrate to Israel, and Semah emigrated from Israel – both had chosen a diasporic existence as a Jewish minority under a Muslim/Christian majority), where he now lives with his partner, Linda Bouws. She runs the institute they co-founded, Metropool – Studio Meritis MaKOM: International Art Projects. My grandmother, Rachel Kazaz, had also been among the displaced Baghdadi Jews. My acquaintance with the pain and the uprooting enabled me to write about the mysterious affair that drove the Jews of Iraq to abandon their property, their culture, and their way of life within just a year; the affair that involved bombing Jewish centers in Baghdad, including the synagogue of Semah’s grandfather. [i]

The religious component is always present in Semah’s art, in both form and content, as Judaism provides him with continual context. In some works, mostly those that look upon Israel as an object, he also addresses the Middle-Eastern identity. For instance, the work from the series My Beloved Country – That Did Not Love Me (1977) shows Israel as an alien white slice cut from a carpet of the Middle East. The carpet signifies an area, and also a place where Jews, Muslims, and others offer their prayers.[ii] The scholar Shlomit Lir wrote in the past year: “In My Beloved Country- That Did Not Love Me Joseph Semah demonstrates the binary perception and the Orientalist gaze by placing an outline of the map of Israel on top of a Persian rug. The virulent contrast created by the coupling of these two elements emphasizes an act of deletion where there should have been geographical continuity. The installation points to a place of conflict and unresolved dissonance between the Middle-eastern space, represented here by the brightly embroidered rug, and Israel, represented as a uniformly white cutout in the shape of the country’s map.”[iii]

Joseph Sassoon Semah, My Beloved Country – That Did Not Love Me, metal clothes hanger and egg-shaped marble, 33 cm, 1977 Photography: Ilya Rabinovich – Courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semah

In the early 1990s, the well-known curator Sarit Shapira identified another central theme in Semah’s art – the motif of the victim. She wrote about it: “…in his work, too, it is handled through linkage to a Biblical myth.”[iv] Shapira discerns Semah’s process of reversal: rather than a discussion by the Christian culture about the place of the Jew within it, the Jew is viewing Christian society as the ‘other.’ “The production of paintings and sculpture in the West, Semah argues, is tainted by this Christian lust. His treatment of the border line between Judaism and Christianity is a maneuver that allows him to observe, from a remove, from the position of the ‘other,’ both the culture and his own Jewish-Israeli one.”[v]

If we looked closely at art that is being made in Israel today, we could detect the influence of Semah’s work, like the influence of other Mizrahi émigré artists such as Meir Gal, who is also mentioned by Shlomit Lir in her academic paper.[vi] However, throughout his years in Israel Semah has always been considered a bird of a different feather. The few, select occasions on which he has exhibited in Israel include “Routes of Wandering” at the Israel Museum (1991), curated by Sarit Shapira, and the Israel Festival of 1986, under the directorship of Oded Kotler, when his work, Take Sand and its Shadow is Blue (As the Mountains Surround Jerusalem), was presented near Armon HaNatziv, the headquarters of the British high commissioner in the 1930s and 1940s, built on the what had previously been the border between Israel and Jordan. For this work, Semah installed a series of blue cocoons that marked the seam between east and west.[vii]

Over the last forty years Semah has been preoccupied with identifying the strategy of the Western Imperium, to uncover its blank pages and through them to reveal that which is hidden, concealed – the universal Jewish narrative. His method is quite simple: he studies the canonical works of Western art by writing his interpretations of them. Sometimes, his artworks become footnotes in the text he is writing.

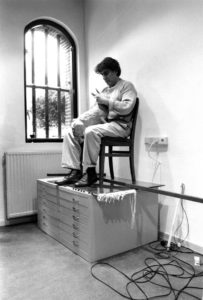

The 26th of November, 1965, Düsseldorf, Germany: Joseph Beuys is inside a gallery, an audience is watching him from outside. His head is smeared with honey and gold leaf, and he is holding a dead hare in his arms. He named the performance “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare.” Beuys strolled along the walls of the gallery, which were hung with his Brown Cross (Braunkreuz) paintings– crosses painted with the hare’s blood – explaining them in a language unintelligible to the hare. Beuys died on January 23, 1986. And on February 24, 1986, on his birthday, Semah put on a performance, How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist (“hare hunting” was a euphemism for killing Jews during the Holocaust). It was Jewish theological tradition’s answer to Beuys, going back in time to Esau, who had come back from the hunt with a hare (a non-kosher animal) and thus lost his father’s blessing to his brother Jacob. The image of Esau with the dead hare slung over his shoulder is featured in many paintings in major European churches.[viii]

Joseph Sassoon Semah, Take Sand and its Shadow is Blue (As the Mountains Surround Jerusalem). Wire net covered in concrete and blue paint, 1986 Photography: The Israel Festival – Courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semah

Mati Shemoelof: Have you met Beuys?

Joseph Sassoon Semah: I met him twice. Once in Berlin, at the National Gallery. He was a kind man, and he invited me to his home, but I didn’t go. We met again, also in Berlin, and talked for half an hour. Yes, he was aware of my work, but he was the clean, pure face of Germany after WWII, and myself a young artist.

MS: Your work reminds me of the writing of the Babylonian Talmud, in the sense that the interpretations are independent creations, and of Jewish literature, which is inter-textual and gathers in the layered writings of sages from different times. And you created a piece on the subject of the Babylonian Talmud, which was banned.

JSS: I couldn’t show An Introduction to the Principle of Relative Expression (1979), in which I have covered pages from the Babylonian Talmud in black paint. Moti (Mordechai) Omer, the late director of the Tel Aviv Museum, told me, in our last conversation, that he would “display these works at the Tel Aviv Museum over my dead body.” The first and last to show it was the curator Gideon Ofrat, at the “Time for Art” (zman le-omanut) space in Tel Aviv, in 2002.

According to Semah, Omer’s reaction, from thirty years ago, was a rejection of his symbolism and a result of the difficulty to understand his context as a Babylonian Jew. In the rejected work, he covered pages from the Babylonian Talmud in black paint intersected with white lines that marked entry and exit points to and from the Talmud. The same work was shown twenty years later in an exhibition curated by Gideon Ofrat.[ix] Perhaps Ofrat had understood the context and seen the work’s artistic value, which seems obvious today, with the increased recognition of the Jewish component in Israeli art. Omer was not alone in declining to show Semah’s works. According to the latter, Yigal Zalmona, of the Israel Museum, and Galia Bar Or, of the Mishkan Museum of Art at Ein Harod, rejected his work as well.

Joseph Sassoon Semah, How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist, February 24, 1986 Photography: Olaf Bergmann – Courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semah

In 1979, the year Semah’s father died, Israel has died for him too, he says, and he had been reborn as a Babylonian Jew. From within the canonical European art, Semah has discovered that he was a guest, the ‘other.’ The discovery created a hidden, delicate equilibrium between the new personal identity (a Babylonian Jew), and his position in the West, that is Europe – being a universal Jew.

MS: Do the Dutch accept your artistic critique of the Holocaust discourse?

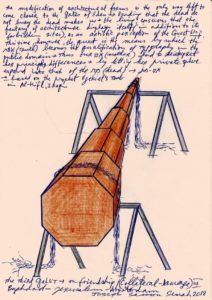

SJS: Since I started the project On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) with Linda Bouws, in 2015, the art world and the Dutch in general begun to comprehend the research in its entirety.

The project Semah is referring to will manifest itself this year, 2019, under a double title, comprising two subjects: “The Third GaLUT – Baghdad , Jerusalem, Amsterdam – On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) III.” He will reveal his full name for the first time – Joseph Sassoon Semah, the Babylonian Jew, of the third Exile (GaLUT). The project, created in collaboration with Linda Bouws, will be extended to Jerusalem and Baghdad as well. He will construct architectural models of the homes and synagogues and burial places of the Jews of Iraq, including his grandfather’s Meir Tweig synagogue and the tomb of the prophet Ezekiel (which is located about 100 kilometers outside Baghdad). He will present these models in public and private spaces in Amsterdam. With the help of local activists, Semah is planning to build, in close proximity to the Meir Tweig synagogue, where his grandfather had served as chief rabbi, The Doubling of the House – a house in which the entrance and the window form the Hebrew letters for chai (ח”י) – the letters that represent the number 18, and also mean “living.” The same structure will also be raised in Amsterdam. Today there are no Jews left in Baghdad. That is, Babylonian Jewry has been erased twice – once in Iraq, and for the second time in Israel. The very construction of the house opposite the synagogue proves that the Jews of Iraq are alive and present. Unlike works like Yael Bartana’s …and Europe Will be Stunned, here there is no repatriation of Iraqi Jews to Baghdad; there is only an anguished howl.

An Introduction to the Principle of Relative Expression, 1979, black oil crayon on pages from the Babylonian Talmud, 27X40 cm each Courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semah

“To begin with, GaLUT is neither Exile, nor Diaspora, nor an existing Place; GaLUT is simply a disciplined activity, an intensive vision, and it is what GaLUT proceeds to do – to transform each and every temporary MaKOM of shelter, into a perpetual search for a Handful of Soil. At this point, one can say that the depiction of MaKOM in GaLUT is an idea of a constant doubling; A double mirror-image of itself by itself. But behind all these, there is another reality, that is of an absolute Reading, to be defined in terms of the enduring action of Writing.” (Joseph Sassoon Semah, 1986)[x]

MS: You make use of of the various meanings of the Hebrew words makom(place) and galut (exile), and find in their combination the term “city of refuge,” or “shelter.” This term resonates the public bomb shelters, which are non-existent in Europe but are part and parcel of Israeli epistemology, and also resonates to a place of escape – to immigration – and the search for a city of refuge. In biblical times, the six cities of refuge were in Transjordan.

JSS: We’ve served in the military, in addition to other things, and its business is to kill. We kill directly and indirectly. The army is not about dancing. In 1986 I made Amsterdam my city of refuge, and there I publicly confessed my past as a soldier.

The correspondence between Semah and myself is not related only to identity, Mizrahiness, ethnicity, or Jewishness – it is also about place. We both are Jews living in Europe, conducting a dialog with Israel that had defined us as subjects, and with the European continent. We have no choice but to deal with the multiple states of mind that had established the Jewish identity as we know it, without us (Iraqi Jews in particular, and Arab-Jews in general) having ever taken part in this continuum of thought and cultural production shared by the those who established the three identities we are confronting – either the Jewish-Israeli identity, the Jewish-European, or the European one.

Joseph Sassoon Semah, study based on the Meir Tweig synagogue in Baghdad, Iraq, from On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) III – The Third GaLUT – Baghdad, Jerusalem, Amsterdam, pen and pencil and paper,42X30 cm, 2018 – Courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semah

Joseph Sassoon Semah, study based on the the tomb of the Prophet Ezekiel, al Kifal, Iraq, from On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) III – The Third GaLUT – Baghdad, Jerusalem, Amsterdam, pen and pencil on paper,42X30 cm, 2018- Courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semaht

MS: Your criticism reaches far, as far as Martin Luther and his anti-Semitism. In 2017, you were permitted to present an intricate work in Nieuwe Kerk cathedral in Amsterdam. It contained your name, among other things, written above Luther’s. It is interesting to me that you, as a Babylonian Jew, are reversing the figure of the Jew in the very heart of Christian culture, even though our ancestors come from a different culture. You assume a task of deconstruction that contains an element of masquerade.

JSS: We connected to Martin Luther in this project by way of the 500th anniversary of his achievements, but the research had been written already thirty years ago. I can explain the connection to Luther as a private investigation – going back to things I explored thirty years ago in Berlin. Let us not forget, there has been an exclusion of the Mizrahi Jews in Israel, and we hardly ever listened to Arab music or read Arab literature. Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust became our origins. The establishment and the education system erased the culture of the Babylonian Jewry. Although I had not been a part of the Mizrahi struggle, after many years in Europe, and through study, I returned to the identity I had lost in Israel.

Notes:

[i] Shemoelof, Mati, “We are Writing a Nation State:– the Case of the immigration of the Jews of Iraq.” See:https://matityaho.com/2012/10/09/אנחנו-כותבים-אותך-מולדת-המקרה-של/

[ii]Lir Shlomit, “Black Panther White Cube: The Exhibition that Wasn’t Shown,” Visual culture in Israel: An anthology, Edited by Sivan Rajuan, Noa Hazan (Shenkar College: Ramat Gan and Hakibbuz Hameuhad Publishing: Tel Aviv, 2017), p. 322.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Shapira, Sarit, Routes of Wandering: Nomadism, Voyages and Transitions in Contemporary Israeli Art. (Jerusalem: Israel Museum), 1991, p. 163 (in Hebrew). This quote was translated by the translator of the current essay.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] See Lir. p. 322.

[vii] This performance was restaged in 2007 at a church in Hildesheim, as part of a large project called Next Year in Jerusalem, which took place in 12 churches throughout the Hanover region in Lower Saxony, Germany.

[viii ]See also: Gideon Ofrat, The Return to the Shteitel (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute. 2001)

[ix] See Ofrat’s article about this work here, pp 52-53 of the PDF (in Hebrew)

[x] From the manifest Joseph Sassoon Semah wrote for his the project City of Refuge (Epistemic MaKOM), created in Amsterdam in 1986.

Joseph Sassoon Semah, MaKOM (The Doubling of the House), 200X200X200 cm, cement blocks, with entrance and window, 1979-2019 Photography: Ilya Rabinovich Courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semah

Previously published: http://tohumagazine.com/how-explain-hare-hunting-dead-german-artist?