Uncle Duke

From: Gary Trudeau – Doonesbury

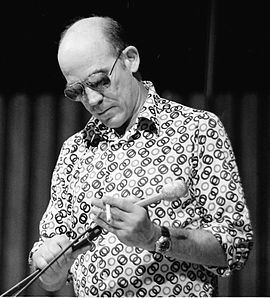

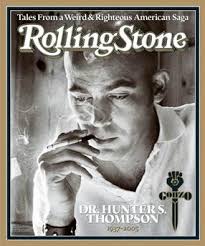

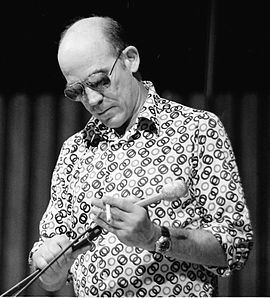

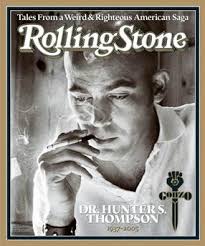

Hunter S. Thompson, the counter culture ‘gonzo’ journalist, died on February 20, 2005 by a weapon of his choice. The inventor of Shotgun Art and Shotgun Golf fatally shot himself at his Owl Creek farm in Woody Creek, Colorado. He was 67.

‘Prince of Gonzo’ he called himself, ‘Doctor Gonzo’, ‘Doctor of Journalism’, ‘Outlaw Journalist’, ‘Doc’, ‘The Duke’: Hunter Stockton Thompson (Louisville, Kentucky, 1939).

Rock star of the written word.

And as with rock stars meeting one is never an easy task. But we managed, once, after endless waiting and drinking our way into the local bar, The Woody Creek tavern. The sun was already sinking behind the Rocky Mountains, bathing the area around the Tavern in a chill and cheerless light, when finally the great Doctor made his appearance. Five in the morning would have been a more approriate time.

Word had it that Thompson was burned out. That, battle weary, he’d given up on the Gonzo cause. Gonzo comes from the French-Canadian word gonzeaux which means something along the lines of shining path. Hunter Thompson was that path; the only fully fledged grand master of Gonzo. His Gonzo style was often confused with New Journalism, made famous by Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese. But that is quite incorrect. Wolfe and the like attack the truth with the techniques of the novelist. They lose themselves in the minds of their subjects. Thompson lost himself in his own mind, and traced only his own madcap, hallucinatory journey through the many events in his stories. “It’s essentially a ‘what if’,” as P. J. O’Rourke, another Rolling Stone celebrity, quoted Thompson.

The style evolved in 1970 when he failed to meet a deadline and in blind panic sent in his notes instead. They were greeted with cheers. The article ‘The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved’ appeared in Scanlan’s Monthly in June 1970. An inflammatory story apparently written at one sitting. It covers the horse race, the failure of the American Dream and, of course, Richard Nixon. Because Gonzo is not just a style of journalism, it is a battle for the preservation of Freedom and the American Dream. The Gonzo cause. And that is inextricably bound up with politics.

The basis for his political involvement was formed in 1968. A year earlier Thompson had published ‘Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs’, and the book had caused considerable upheaval. Editors of the most famous magazines were queueing up to hire him.

That year the magazine Pageant gave him an assignment to write a piece about Nixon’s political resurrection. (Nobody expected him to return to the political arena after his defeat by Kennedy in 1960.)

Having arrived in New Hampshire, where Nixon was campaigning, it turned out to be impossible to speak to the man in person. Nixon had instructed his staff that he would not speak about Vietnam or political campus demonstrations. No, the furthest he would go was to talk to an insider about football. While the Republican candidate was preparing for the drive to the airport, a campaign worker remembered that Thompson knew all there was to know about sport. He and he alone was allowed to come along. Nixon had the edge on him with his knowledge, but Thompson could respect that. Nevertheless, the two could never get along from that moment on. More to the point, Thompson found his journalistic raison d’être, although neither of the two realised it at the time. In the July issue of Pageant 1968 the article appears “Presenting: The Richard Nixon Doll”.

Having arrived in New Hampshire, where Nixon was campaigning, it turned out to be impossible to speak to the man in person. Nixon had instructed his staff that he would not speak about Vietnam or political campus demonstrations. No, the furthest he would go was to talk to an insider about football. While the Republican candidate was preparing for the drive to the airport, a campaign worker remembered that Thompson knew all there was to know about sport. He and he alone was allowed to come along. Nixon had the edge on him with his knowledge, but Thompson could respect that. Nevertheless, the two could never get along from that moment on. More to the point, Thompson found his journalistic raison d’être, although neither of the two realised it at the time. In the July issue of Pageant 1968 the article appears “Presenting: The Richard Nixon Doll”.

In August of that year Thompson was present at the historic Democratic Convention in Chicago. A pitched battle between police and anti-Vietnam demonstrators broke out outside the convention hall. In the confusion Thompson fell through a glass door and was injured. Weeks later he still could not speak about the incident without bursting into tears: his faith in politics had been irrevocably damaged. He realised the futility of national politics and decides, from that moment on, to concentrate solely on his own home ground: what had been personal became political. “I went to the Democratic Convention as a journalist, and returned a raving beast,” he announced.

‘It was the built-in blind spots of the Objective rules and dogma that allowed Nixon to slither into the White House in the first place,’ the Doc wrote a quarter of a century later in ‘He was a Crook’, the obituary he penned for Nixon from Woody Creek upon the man’s descent into hell. ‘He looked so good on paper that you could almost vote for him sight unseen. He seemed so all-American (…) that he was able to slip through the cracks of Objective Journalism. You had to get Subjective to see Nixon clearly, and the shock of recognition was often painful.’

The Tavern was Thompson’s home base. It is a wooden construction that wouldn’t look out of place in a road-movie. Outside, above the door, a stuffed wild boar replete with yellow spectacles and decorated with coloured lights inspects the clientele. Next door to the Tavern is the post office and apart from that there’s no more to Woody Creek than a few substantial remote wooden houses and a trailer camp. The Tavern is Woody Creek. It’s a ten minute drive to the airfield serving the fashionable ski-resort Aspen, frequented mostly by private jets.

Inside there is a pleasantly decadent atmosphere. You’re conspicuous wearing anything other than a lumberjack shirt and cap. Both men and women walk around in cowboy boots and all the regulars appear to have accepted postponement of their own American Dream. Comfort is to be found in the whining country music continually blaring out of the loudspeakers. And in the booze, of course. The walls are filled with newspaper cuttings and photographs, paintings of wild-west scenes, an enormous stuffed shark, pictures of legendary baseball players and postcards from every corner of the world. At the back there’s a pool table. From one end of the ceiling to the other there’s a string from which hang hundreds of little pink pigs. At the bar, folk speculate amusedly about how long the Doc has to go in this far from perfect existence, the wildest stories circulate concerning both his liver and his nose cartilage.

And stories about Thompson are what keep and maybe will keep the Tavern running: dozens of Doc-heads visit this structure every year, hoping to catch a glimpse of their hero, mostly in vain. There’s even a Doc-corner decorated with pieces of text from the Rolling Stone, the rock magazine that published many of his searches for the Dream; and assorted articles from the local press and dozens of snapshots. At the bar they will, swear Thompson was quite prepared to shoot trespassers on his property. The Thompson-corner is dominated by the famous photograph that Annie Leibovitz took of him in 1987: Hunter stretched out on a Harley Davidson, his eyes fixed thoughtfully heavenward behind his dark pilot’s glasses, short trousers, white knee length socks, and tennis shoes, taking a drag on a Dunhill in a cigarette holder wedged between his thin lips.

We had brought a bottle of Chivas Regal for the special occasion. One of his favourites. We would’ve gladly brought him some skunk, but were afraid the American authorities wouldn’t have let us get away with it. A fear encouraged by Thompson himself, he had a healthy respect for the American customs officers. In the hilarious title story of his book ‘The Great Shark Hunt: Strange Tales from a Strange Time. Gonzo Papers Vol.I’ he went to Mexico in 1974 for Playboy to cover the cruise and international fishing tournament at Cozumel. As he had hidden a quantity of drugs left over from another story in a nearby hotel, the assignment appealed to him. Together with his friend Yail Bloor Thompson leaves for Mexico, where the two are quickly bored to death after just a day and a half on a boat. But then things began to liven up, parties, enormous quantities of drink, coke, LSD, and speed. After a short time they didn’t know whether it was day or night. Mostly night. They were not there for the fishing although they did make one valiant attempt in the struggle between man and shark. The sharks were nowhere to be found. Thompson and Bloor decided it was time to flee the picturesque town of Cozumel leaving a trail of unpaid bills behind them.

We had brought a bottle of Chivas Regal for the special occasion. One of his favourites. We would’ve gladly brought him some skunk, but were afraid the American authorities wouldn’t have let us get away with it. A fear encouraged by Thompson himself, he had a healthy respect for the American customs officers. In the hilarious title story of his book ‘The Great Shark Hunt: Strange Tales from a Strange Time. Gonzo Papers Vol.I’ he went to Mexico in 1974 for Playboy to cover the cruise and international fishing tournament at Cozumel. As he had hidden a quantity of drugs left over from another story in a nearby hotel, the assignment appealed to him. Together with his friend Yail Bloor Thompson leaves for Mexico, where the two are quickly bored to death after just a day and a half on a boat. But then things began to liven up, parties, enormous quantities of drink, coke, LSD, and speed. After a short time they didn’t know whether it was day or night. Mostly night. They were not there for the fishing although they did make one valiant attempt in the struggle between man and shark. The sharks were nowhere to be found. Thompson and Bloor decided it was time to flee the picturesque town of Cozumel leaving a trail of unpaid bills behind them.

“ There’s only two things I’ve never done with drugs: sell them or take them through Customs,” Thompson confessed to Bloor on the flight to Denver. Bloor couldn’t believe his ears, knowing the lethal amount of pills and powders contained in Hunter’s suitcase.

The first stop was Monterrey, Texas. And the nearer they got, the more it began to dawn on Thompson that Texas does not go easy on drugs smugglers. He had a brilliant idea, they would eat all the drugs. After a few mescaline tablets, six LSD tablets, one and a half grammes of pure cocaine, four joints, ten speed pills and some MDA (the hallucinatory little brother of MDMA or XTC, – ed.) they stumbled out of the aeroplane.

At the bar the two friends calmed themselves with a few margaritas laced with tequilla. The mist cleared. All of a sudden they heared their names announced over the loudspeakers. Blind panic overcame Bloor. He stood in the toilet trying to piss, snort coke and smoke a joint all at the same time. Thompson was lost in an apocalyptic vision, sees officers walking towards him and is convinced that he’ll spend the next few years rotting in jail. To soften the blow he washed down the last few speed tablets and the two of them amble towards the gate.

They got to the next stop, San Antonio, one of the most heavily guarded airports in the United States. Just as he was haggling with a customs officer about the amount of tax to be paid on their bottles of tequilla, four orange balls of hallucinatory powder tumble out of Thompson’s trouser pocket. Bloor started to giggle uncontrollably. The Doc stayed cool: he bends down, picks the balls up, and puts them nonchalantly back in his pocket. He ended the Playboy story saying: “(..) nobody with even latent inclinations to use drugs should ever try to smuggle them.”

Hunter S. Thompson

Photo: en.wikipedia.org

The crowd raised hands and clenched fists as a greeting when Thompson stepped into the Tavern. He returned the welcome, stood for a moment soaking up the attention triumphantly and then strode over to his corner. His movements seemed exaggerratedly controlled, like those of an old man. His clothing set him apart from the rest of the clientele: a silver coloured jacket with insignia, fingerless gloves, a glass of gin in one hand, cigarette holder in the other and the famous Confederate cavalry hat on his head, the style he’d been wearing since junior school. Readers of Garry Trudeau’s comic strip Doonesbury will still recognise him immediately. Doonesbury is modelled on the Doc – short trousers, knee-length socks, cigarette holder – and to the great annoyance of the Doc he didn’t receive one cent for it. Meanwhile whole generations grew up thinking that Thompson is imitating a comic strip character.

Thompson pushed the Chivas to the side of the table and raised a hand to place an order. Beer. He was once at a table with former Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern and his wife and ordered two margaritas, a glass of wine and a bottle of beer. When the waiter remarked that he’d ordered four drinks for three people Thompson said: “Bring me the goddamned drinks! I don’t know what these bastards want.”

Thompson searched through his pockets, looking for a lighter.

“Smoking in the Tavern is not allowed,” he told us, but for him they make an exception. He had brought some marijuana with him and put it on the table. According to E. Jean Carroll’s schedule in “The strange and savage life of Hunter S. Thompson” it’s time for a joint. Carroll recorded that Thompson would usually rise at 3 p.m. with a Chivas and a Dunhill and go to sleep at 8 a.m. only after a hot tub.

A tight schedule, if slightly unusual. He could fly into a rage if the newspaper or his Chivas would not be at hand. As the great love of his life Sandy, long since his ex and mother of his son Juan Fitzgerald found out the hard way. In 1972 Thompson was told that he had only a year to live and since then his name has ranked high in The Death Game – a morbid game in the U.S. in which players bet on the list of deaths in The New York Times. All bets are off now. Ralp Steadman, his friend and illustrator was already doing sketches of Hunter’s liver years ago, as the man was long overdone, as he said.

What are you up to these days, we asked him.

“Polo, he said. “I’m a sportsman, you know. I’m busy writing a book: ‘Polo is my Life’. ”The first reports of this project date from 1967 and the title kept on cropping up in interviews and reviews ever since. It was one of many unfinished projects he took upon the last ten years of his life. “It’s about sex and treachery. Betrayal. One hundred percent fiction. All Gonzo inspiration.”

Smiling, he fished a scorched black hash-pipe from his jacket pocket and a lump of hash as big as a ping-pong ball. Thompson didn’t speak, he issued grunts. Staccato. It sounds like offended muttering. “This is a personal thing”, he said. “I can smoke here. It’s not against the law.” But then, from behind the bar an enormous redneck walked menacingly towards us and asked Thompson with no uncertain insistence not to smoke. He ostentatiously took a few more draws on the cigarette and put it out.

In most of Thompson’s stories and articles he invoked a certain ‘Bubba’ , a person who stood for all Doc-heads, readers and fellow fighters for the Gonzo cause. Bubba looks sadly on, just like Thompson, as the American Dream is slowly but surely dismembered. And neither Bubba nor the verbal violence that Thompson brought to bear in his reports could do a thing about it. One of the bubba’s is Bob Braudis, long time sheriff of the Pitkin County. He was around in 1970 when Thompson as leader of the Freak Power Party made his bid for the title. Thompson had fled Haight-Ashbury, the hippie-mecca of San Francisco where Rolling Stone had sent him, at the time of his political awakening, in 1968. He sought sanctuary in Woody Creek.

Thompson fought his campaign from the Jerome Bar, the oldest bar in Aspen where even now the Freak Power Party’s election poster still has pride of place above the bar. It shows a giant sheriff’s star and in that the party’s insignia: a clenched fist with a thumb on both sides. Later the Gonzo insignia. The second item in his manifesto: changing the town’s name from Aspen to Fat City. He wanted to prevent that the whole valley should fall into the hands of property-speculators and greed-heads. Once he was in office, Thompson promised, he would reserve a number of days in the week for ‘psychedelic experiments’. His opponent, Carroll Whitmire, had crew-cut hair, like all the all-American-boys. Thompson therefore decided to shave his head completely bald in order to be able to refer to Whitmire as ‘my long-haired opponent’ in debate.

Thompson stuck to journalism, mercifully, he fell 468 votes short of victory. A close shave, but they have never shaken him off completely: he was long active in local politics, and was almost single-handedly responsible for the fact that the planned extension of the local airfield had been postponed for more than 25 years. Thompson quoted Dostoievski on the subject: “Democracy is the art of controlling your environment.” Braudis said the same thing to us: “The Gonzo cause for me is freedom from control, intellectual freedom. Enlightenment. Give somebody a little power and he will become a nazi. The United States are heading that way: The United States of Control.”

Thompson lit yet another Dunhill, threw his Zippo in the air and caught it, mid-air. “Look, I’m not drunk…” An old trick, a similar incident was described in ‘Fear and Loathing: The Terrible Saga of Hunter S. Thompson’ a biography written by Paul Perry. With a few Rolling Stone colleagues in 1972 Thompson threw his sunglasses above his head and catched them mid-air in order to prove to a police officer that he couldn’t possibly be drunk. He was allowed to drive on, despite the clearly visible bottle of Wild Turkey and the reek of mescaline and bourbon.

Thompson lit yet another Dunhill, threw his Zippo in the air and caught it, mid-air. “Look, I’m not drunk…” An old trick, a similar incident was described in ‘Fear and Loathing: The Terrible Saga of Hunter S. Thompson’ a biography written by Paul Perry. With a few Rolling Stone colleagues in 1972 Thompson threw his sunglasses above his head and catched them mid-air in order to prove to a police officer that he couldn’t possibly be drunk. He was allowed to drive on, despite the clearly visible bottle of Wild Turkey and the reek of mescaline and bourbon.

Thompson’s Gonzo pieces in the Rolling Stone magazine had brought them recognition and increased circulation. So it was that he was sent out to Las Vegas by the magazine. It culminated in his best-known and best-selling book ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ (1971). In that book he described an incident where a traffic-cop stopped him and emptied the can of Budweiser Thompson had been drinking onto the road.

“It was getting warm anyway,” Thompson had remarked. At least ten more cans lay baking in the sun on the back seat of the Great Red Shark – his Chevrolet convertible. Same trick, same result, he was given a warning and allowed to drive on. The book was turned into a movie by director Terry Gilliam and with Johnny Depp as Thompson. They spent hours together improving their shotgun capabilities in Thompsons backyard. Depp will also play the main character in The Rum Diary, named after Thompson’s novel published in 1998.

In ‘The Proud Highway’ Thompson published his letters from 1955 until 1968. “They go back a long time,” he said, “ from when I was some bezirk kid.”

Little Gonzo stood crying in front of the judge that year. Together with two rich young friends he had been caught stealing. The judge sentences him to sixty days in a youth prison. After that he was to report to the army or a special school. The sentence came eleven days before the final exams at high school. Thompson was never to get that diploma. His little rich friends got off scott-free.

The sentence had a powerful effect on him and provided his anger and hatred of authority with enough fuel for the next forty years. He followed a correspondence course in the Jefferson County Jail and made a start on his literary career. After thirty days he was released on good behaviour and reports immediately to the air force, where he weedled himself a job as sports journalist.

Thompson: “Nobody was prepared for the letters that I had. For a reason I saved them all. I didn’t care much. Until my son and a bunch of strangers read my letters in front of me. Until ’68 ordinary letters, after that I started to write politically.

“7000 pages were delivered to Random House. That was after the first cut. They have pictures at Random House, like this high, 3, 4 feet. Maybe three or four volumes, I don’t know yet. Insane.” In 2000 the second volume was published, ‘Fear and Loathing in America’, with the letters from 1968 unto 1976.

The Duke turned to other matters, once more. He wanted to fill the hash-pipe, but noticed the sheriff coming in. “Shit. It’s too much for the pipe.” The fuss is extraordinarily awkward, touching. As the sheriff came in Thompson slipped past him out of the door out to his car.

Thompson sat huddled in his jeep and smoked the pipe at his leisure, looking out at the wild boar with the yellow spectacles. The sheriff glanced out at the jeep, saw whisps of smoke coming out of the opened windows and said: “Hunter has been in the booking room, but he never spent the night and I doubt that he ever will. There are some misconceptions about Hunter. He only drinks when he’s awake, but he doesn’t get drunk. I’ve been there with him. In a three-hour-period I drink way more than he does. Over 24 hours he’ll drink way more. He is a professional drinker but he never loses his equilibrium, he’s always centred. He is a very intelligent man, doing what he is good at. Writing and drinking.”

Thompson enjoyed every inch of the road that took us to his ground: Owl Farm, his house in the hills. Flat out, braking at the last possible moment, using the verge as a continuation of the road. In short the style of driving he propagated in ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’:

Thompson enjoyed every inch of the road that took us to his ground: Owl Farm, his house in the hills. Flat out, braking at the last possible moment, using the verge as a continuation of the road. In short the style of driving he propagated in ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’:

‘The thing to do-when you’re running along about a hundred or so and you suddenly find a red-flashing CHP-tracker on your trail-what you want to do then is accelerate. Never pull over with the first siren-howl. Mash it down and make the bastard chase you at speeds up to 120 all the way to the next exit. He will follow. But he won’t know what to make of your blinkersignal that says you’re about to turn right.

‘This is to let him know you’re looking for a proper place to pull of and talk… keep signaling and hope for an off-ramp, one of those uphill side-loops with a sign saying “Max Speed 25”… and the trick, at this point, is to suddenly leave the freeway and take him into the chute at no less than a hundred miles an hour.

He will lock his brakes about the same time you lock yours, but it will take him a moment to realize that he’s about to make a 180-degree turn at this speed… but you will be ready for it, braced for the Gs and the fast heel-toe work, and with any luck at all you will have come to a complete stop off the road at the top of the turn and be standing beside your automobile by the time he catches up.’

Before we knew it we passed the gate to Owl Farm. Thompson summoned us to stick to the rules and pointed to the battle-scarred gun-mount in front of the house. All around lay dozens of empty shells. On the vast lawn around the house a satellite dish lies abandoned where it blew off the roof. Also there were a number of bullet riddled barrels. Here the sportsman practiced his famous shotgun art. This is an art form, of which he is the only exponent: shooting at posters and paintings and golfballs, preferably representing people he hates. It all began when he ordered an enormous pile of J. Edgar Hoover posters and used them as targets, shortly after his arrival at Owl Farm.

‘If it doesn’t explode, it’s not art,’ is a well known saying of his. Doc-heads will pay $10,000 for a shotgun piece. In the shed adjacent stood the famous car: the Great Red Shark. The view was heavenly: mountains and valleys.

With ill-concealed pride Thompson showed us the way to the peacock pen: a glass partitioned outer room of his house, the floor covered in straw, and on this are two wooden cages. A few peacocks were woken from their lethargy, one even spread its tail feathers. “Home at last,” the Doc shouted at them. “Sleep tight.”

Together with the ever-present Bubba we stepped into the house. Braudis remembered the time there was a note on the door saying, “Good morning, I’ve shut myself in the nuts and am unable to come to the door this time for reasons too strange to explain except in crude medical terminology. So therefore, stay away from this door until noon. Do not knock on this door or any other. Do not attempt any form of entry until noon. Thank you. Please wake me at two pm. Best wishes, Hunter S. Thompson.”

“Welcome to Owl Farm” Thompson said, once inside.

He commenced with a routine tour and the first thing we noticed is a framed pair of gold painted boxing gloves. According to the inscription they are the gloves Mohammed Ali wore in the fight for the World Heavyweight Championship against Joe Frazier on 8th March 1971 in Las Vegas. He was a big fan of Ali, even if only because Cassius Clay was born in Louisville. Thompson followed Ali in 1974 to Kinshasa in Zaïre, where Ali is to fight George Foreman. With an advance of $25,000 in his pocket, Thompson is to report on the world-title fight for Rolling Stone. The piece was never written. He went through the money in ten days, according to Ralph Steadman the English artist who illustrated so many of Thompson’s books with his own characteristic drawings.

“I gave the tickets away Ralph,” Thompson barked at Steadman when he asked in panic where the tickets to the fight were. “I told you, I didn’t come all this way to watch a couple of niggers beat the shit out of each other?” He was floating naked on an air mattress in the hotel swimming pool, stoned and scattering marijuana all over the surface of the water.

The interior of his house was reminiscent of the style of the seventies: dark brown, bits and pieces everywhere, hippie-chic. In our efforts to keep up with Hunter we almost knocked over the skeleton of a buffalo. A cloth is draped over it and a spear stuck into the middle. Next to that a small table with a twisted cactus upon which a wajang puppet is stuck. Along the window – which looks out onto the peacocks -a row of LP’s. Thompson always plays music when he’s writing. Loud. Two enormous loudspeakers bear silent witness. The Doc wrote ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ on dexedrine and the rhythm of the songs of J. J. Cale and The Rolling Stones’ Beggar’s Banquet. A side-room of about twenty five square metres looked like an organised disaster area, a merger between a natural history museum and a sport school. From a dartboard Nixon’s mug looked out, there was a Mickey Mouse shot through with bullet-holes, stuffed pheasants, a fox, another skeleton, an Indian headdress, an FBI cap, his polo-gear, the head of a bison and in amongst all this his keep-fit apparatus.

Thompson: “I am a sportsman, you know.”

“This is what you have been waiting for, the big moment,” he announced. “We are about to invade the kitchen. The crisis centre.”

It turned out to be a veritable junk shop filled with political paraphernalia, badges, convention stickers, the Stars & Stripes, bundles of papers piled high, folders and photographs of politicians. The walls were completely covered with newspaper cuttings, letters, congratulations on Thompson Day (18th July), a large film poster of a grinning Bill Murray with shotgun, (Murray played Thompson in the film ‘Where the Buffalo Roam’ in 1980, with music by Neil Young), and a series of photographs of a typewriter being given the shotgun treatment.

Thompson moved straight over to the spot where, hovering between despair and euphoria, he had spent decades of his life. Here on a stool in the corner between the sink and a raised wooden surface that passes for a breakfast bar in other households, he wrote the masterpieces which until this very day undermine the respect that Americans have for national politicians. In ‘Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail 1972’ (covering the election battle between Nixon and George McGovern) he carved up Richard Milhous Nixon so effectively that the then still reigning president carries a moribund odour long before his forced resignation from office.

Thompson moved straight over to the spot where, hovering between despair and euphoria, he had spent decades of his life. Here on a stool in the corner between the sink and a raised wooden surface that passes for a breakfast bar in other households, he wrote the masterpieces which until this very day undermine the respect that Americans have for national politicians. In ‘Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail 1972’ (covering the election battle between Nixon and George McGovern) he carved up Richard Milhous Nixon so effectively that the then still reigning president carries a moribund odour long before his forced resignation from office.

When ‘The Great Shark Hunt’ came out in 1979 the Doc was already a living legend. But then it seemed to go quiet at Owl Farm. The Doc missed a few deadlines and the story went that he’d abandoned the Gonzo cause, that he wasn’t up to it any more. But with ‘Generation of Swine. Gonzo Papers Vol.2: Tales of Shame and Degradation in the ’80’s’ (1988) and ‘Songs of the Doomed. Gonzo Papers Vol.3: More Notes on the Death of the American Dream ‘ (1990) Thompson showed that he was still keeping a watchful eye on his own backyard and the rest of America. And what he saw did not please him at all. As far as the eye could see, yuppies, greed, lies and deceit. It filled him with fear, and loathing.

In the last decade or so the Gonzo style was back to where it started. The tens of thousands of words he once needed to calm the war that was being waged in his head, had been decimated to core texts and drawings on fax paper. Just like the notes he sent to Pageant in 1970. Gonzo in its purest form. Beside him the fax rattled and spewed continually. At the most impossible hours he filed attacks and advice to the White House, his neighbours or to the brother of Ted Turner (CNN). His contacts were still good. His statements razor sharp. His book ‘Better than Sex. Confessions of a Political Junkie, Gonzo Papers 4’ (1994) is a collection of these faxes. That is exactly how they are reproduced in the book and in the Rolling Stone and The San Francisco Examiner.

Bill Clinton owed his first term as president at least in part to Thompson, or rather to the hate that the Doc felt for George Bush. ‘George Bush looked more and more like some kind of half-eaten placenta left behind at the birth of Ronald Reagan,’ Thompson noted of the then president. Thompson visited Little Rock and was intrigued by Clinton’s strategy of entering into discussion about allegations of infidelity even whilst campaigning: “I did not like Bill Clinton until the Gennifer Flowers story came out – his adversity got me interested.”

What really drew him to the Democratic camp was that Clinton had tried to get out of national service at the time of Vietnam. The disappointment started with Clinton’s statement that he hadn’t inhaled the joint. “That’s when I should have realized that he is fake.”

He took a swig of his Chivas and admitted gallantly: “The idea of democracy in the United States starts to falter. I have lost the idea ever to see a decent human being take office in the White House. We are running against people, not for people. That’s not healthy for democracy. The calling of people that run for office in this country is going down drastically since 1972. That year was the hallmark of the American Lifestyle.”

Hidden away on Owl Farm he spent decades at his most hated opponent’s deathbed, Richard Nixon. The Gonzo Papers read like one long stretched out obituary. When the man’s final hour actually came in 1994 Thompson saw all the rats crawl out of their holes one last time. He smoked them out.

“Read this.” He laid out a passage from ‘Better than Sex’ in front of us: ‘Nixon was so agressively evil that he almost glowed at night. He gave no mercy and expected none. He was fun. Get me the text. I wanna hear it.” It is the text of Thompson’s obituary of Nixon, the single most quoted article in almost thirty years of Rolling Stone. Thompson presented it like a painting ready for its shotgun treatment.The author seemed to miss his principle enemy, as if when Nixon died a part of him died too. “Richard Nixon was the real thing, and I will miss him for the hideous clarity that he brought to my understanding of American politics. He brought out the best in me, all the way to the end, and for that I am grateful to him.

He settled down to listen carefully, poured himself another Chivas and said: “This is all you have to know about political journalism. I can add nothing to it.”

‘Some of my best friends have hated Nixon all their lives. My mother hates Nixon, my son hates Nixon, I hate Nixon, and this hatred has brought us together. Nixon laughed when I told him this. “Don’t worry,” he said, “I, too, am a family man, and we feel the same way about you.”’

Hunter started to clap at these words, as if the tension had fallen from his shoulders. He glanced across at Bubba.

“A lot of us came to here in the Rockies in the sixties,” mused the sheriff. “We sat down at the banquet of love and had our desert first. Now we’re eating the lime of beans, we’re slugging through the lime of beans and Brussels sprouts. We’re eating shit but that’s the way we did it. We were the immediate gratifyers of the sixties and seventies and we enjoyed it. We had a lot of fun. But you know, you don’t want to stay at a party too long, you want to leave the party while you’re still having fun. I am still having fun but I’m eating the lime of beans and all those things that you push away. Because we ate the desert first.”

Thompson: “Clinton is white trash. He is not fit to carry Jimmy Carters shoes.” Sighing: “But Carter cleared the way for twelve years of Republican dominance. I blame him for that, I’ve always hated him for that.” In that respect Clinton is on his way to step into Carters shoes. George W. Bush is in for a second term now.

Cover Rolling Stone

Thompson sort of skipped the 1996 and 2000 elections. Too busy with publishing his books. But 2004 was a different matter. ‘On election day I was called by George McGovern. He was ready to rumble: ‘This is it Hunter. This is the day we’ve been waiting for all our lives. Nixon was nothing compared to these bastards. This is the most important election of my lifetime, including my own race.’” One week later Thompson wrote in his column on ESPN: “I’m no stranger to the anguish of losing a presidential campaign, and this very narrow loss with John Kerry is no exeption. (…) Today, the Panzer-like Bush machine controls all three branches of our federal government, the first time that has happened since Calvin Coolidge was in the White House. And that makes it just about impossible to mount any kind of Congressial investigation of a firmly-entrenched president like George Bush.” Thompson was apparently no longer willing or fysically capable to take on George W. as he did with Nixon.

His fight is over. May he rest in peace. Long live the Gonzo cause.

—

© Bas Senstius & Jurrien Dekker

© Translation: IFA-Amsterdam, 2011

Previously published.

Sinds gisteren waait er een koude wind en de regen, die wekenlang bijna dagelijks viel, is afgenomen. Ik hoop maar dat de nattigheid voorbijgaat. De hele week al is er vleesgebrek en moeten we zonder zien uit te komen. Vis is buitensporig duur.

Sinds gisteren waait er een koude wind en de regen, die wekenlang bijna dagelijks viel, is afgenomen. Ik hoop maar dat de nattigheid voorbijgaat. De hele week al is er vleesgebrek en moeten we zonder zien uit te komen. Vis is buitensporig duur.