Jack Kerouac in Parijs

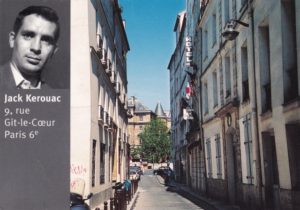

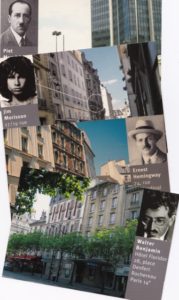

Dit soort ansichtkaarten kun je overal in Parijs kopen. Een foto van een bekende schrijver, pop- of filmster met een foto van het adres waar hij of zij in Parijs gewoond heeft: het adres waar Jim Morrison woonde en stierf (27 Rue de Beautreillis), het hotel waar Walter Benjamin vaak verbleef (Hôtel Floridor) of waar Ernest Hemingway een kamer bewoonde (74 Rue du Cardinal).

Dit soort ansichtkaarten kun je overal in Parijs kopen. Een foto van een bekende schrijver, pop- of filmster met een foto van het adres waar hij of zij in Parijs gewoond heeft: het adres waar Jim Morrison woonde en stierf (27 Rue de Beautreillis), het hotel waar Walter Benjamin vaak verbleef (Hôtel Floridor) of waar Ernest Hemingway een kamer bewoonde (74 Rue du Cardinal).

De kaart met het portret van Jack Kerouac, gevoegd bij het adres 9 Rue Git-le-Coeur moet echter gekwalificeerd worden als een lichte vorm van op toeristen gerichte geschiedvervalsing. Tegelijk wordt er ook nog eens een hardnekkige mythe mee in stand gehouden. Namelijk het verhaal dat Jack Kerouac in de jaren vijftig en zestig enige tijd in het obscure hotel op dat adres gewoond zou hebben.

Beat Hotel

De Rue Git-le-Coeur is een onooglijk straatje ten westen van de Place St. Michel, tussen de Quai des Grands Augustins en de Rue St. André des Arts. In de jaren vijftig en zestig verbleven enkele leden van de groep schrijvers en dichters die als de Beat Generation werd  aangeduid, voor korte of langere tijd in een hotelletje in dit straatje. Het naamloze hotel kreeg daardoor later de bijnaam The Beat Hotel. William Burroughs was de meest frequente bewoner van het hotel. Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso en Peter Orlovsky kwamen op bezoek, bleven een paar dagen of woonden er langere tijd.

aangeduid, voor korte of langere tijd in een hotelletje in dit straatje. Het naamloze hotel kreeg daardoor later de bijnaam The Beat Hotel. William Burroughs was de meest frequente bewoner van het hotel. Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso en Peter Orlovsky kwamen op bezoek, bleven een paar dagen of woonden er langere tijd.

Dat deze schrijvers in Parijs neerstreken was niet zo vreemd. De stad kende een bloeiend cultureel leven, nieuwe kunststromingen bleken er levensvatbaar.

De vrije moraal ten opzichte van seksualiteit, de onbeperkte uitgaansmogelijkheden en de verscheidenheid aan muziekaanbod, boekhandels, theater, fotografie en film, maakten de stad tot een uiterst aantrekkelijke verblijfplaats. Het was mogelijk om er een prettig, onbekommerd leven te kunnen leiden, zelfs met weinig geld tot je beschikking. Al in de jaren twintig was de stad een gewilde verblijfplaats voor beginnende schrijvers als James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway en Ford Madox Ford. Zeker voor niet-Europese schrijvers en journalisten betekende verblijf in de stad ook vaak een ontsnapping uit een bekrompen opvoeding, een conservatief milieu of een kleinburgerlijke werkomgeving.

Schrijvers en dichters

In de jaren vijftig werd Parijs opnieuw de stad ‘waar het gebeurde’. Europa herstelde zich van de Tweede Wereldoorlog, en Parijs was de stad waar de voorhoede van een nieuwe toekomst zich leek te kunnen manifesteren. Nieuwe stromingen in kunst, cultuur en filosofie kondigden zich aan. Hoogwaardige journalistiek – de International Herald Tribune vindt zijn oorsprong in Parijs – en literaire tijdschriften als The Paris Review en Les Temps Modernes (onder redactie van Jean-Paul Sartre en Simone de Beauvoir) bepaalden mede het sociaal-culturele klimaat. In diezelfde periode spetterde in de café’s in St. Germain de bebopjazz en verlegde de Nouvelle Vague in de bioscopen de grenzen van de filmwereld.

Dit alles maakte Parijs tot een aantrekkelijke stad voor schrijvers, dichters en kunstenaars. Ook voor diegenen die in hun metier nog geen voet aan de grond hadden gekregen. Beginnend dichter Gregory Corso nam als eerste van de groep Beat-auteurs zijn intrede in het hotel. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs en Peter Orlovsky volgden. Tussen 1957 en 1963 verbleven ze er meerdere malen een paar weken, soms enkele maanden. Voor Burroughs, die dankzij een familietoelage iets ruimer in zijn financiën zat dan de anderen, was Parijs ook een aantrekkelijke tussenstop op weg naar Marokko, waar hij vaak langere tijd verbleef.

Dit alles maakte Parijs tot een aantrekkelijke stad voor schrijvers, dichters en kunstenaars. Ook voor diegenen die in hun metier nog geen voet aan de grond hadden gekregen. Beginnend dichter Gregory Corso nam als eerste van de groep Beat-auteurs zijn intrede in het hotel. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs en Peter Orlovsky volgden. Tussen 1957 en 1963 verbleven ze er meerdere malen een paar weken, soms enkele maanden. Voor Burroughs, die dankzij een familietoelage iets ruimer in zijn financiën zat dan de anderen, was Parijs ook een aantrekkelijke tussenstop op weg naar Marokko, waar hij vaak langere tijd verbleef.

Burroughs en de anderen waren notoire gebruikers van geestverruimende middelen. In Parijs was het niet moeilijk om aan drugs te komen. Ook dat maakte de stad aantrekkelijk. Amerikaanse jazzmusici als Chet Baker, Bud Powell en Miles Davis verbleven om die reden in dezelfde tijd graag in Parijs.

Inspiratie

In 1933 was het echtpaar Rachou in een oud pand in de Rue Git-le-Coeur een goedkoop hotel begonnen. Na de dood van haar man in 1957 dreef Madame Rachou de zaak in haar eentje. Comfort was er nauwelijks in het hotel, al zorgde Madame Rachou wel dagelijks voor een goedkope maaltijd. Er was een gemeenschappelijke badkamer en iedere verdieping had een WC. Maar de kamers waren koud en donker. Gregory Corso had op zijn zolderkamer een kookstelletje waarop hij een maaltijd kon bereiden.

Burroughs verbleef meestal op zijn hotelkamer en kwam alleen de deur uit voor frequente bezoeken aan zijn psychoanalyticus. De anderen zwierven overdag over de kades langs de Seine of filosofeerden middagen lang in het Jardin du Luxembourg.

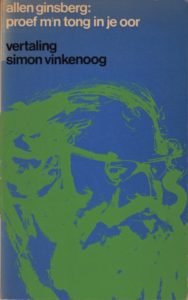

Blijkbaar leverde de stad het groepje schrijvers veel inspiratie op. In het hotel schreef Allen Ginsberg enkele van zijn bekendste gedichten zoals To Aunt Rose en At Appollinaire’s Grave en een lang stuk van Kaddish, zijn beroemde gedicht voor zijn moeder. Gregory Corso schreef er zijn bekendste gedicht Bomb en Burroughs voltooide er zijn Naked Lunch.

Heimwee

Jack Kerouac werd na de publicatie van On the Road de belangrijkste exponent van de Beat Generation. Zijn royalty’s stelden hem in staat soms geld te lenen aan de in Parijs verblijvende vrienden, en om reizen te maken naar Mexico en Marokko. In tegenstelling tot wat sommige auteurs in publicaties over de Beat Generation beweren, verbleef hij nooit in het hotel in de Rue Git-le-Coeur.

De Engelse auteur Barry Miles schreef een boek over de connectie van de Beat-schrijvers met het hotel in Parijs: The Beat Hotel, Ginsberg, Burroughs & Corso in Paris 1957-1963. Volgens Miles kwam Kerouac bij een bezoek aan Parijs één keer kijken in het hotel toen Ginsberg en Corso er verbleven. Maar hij vond het er smerig, de WC’s stonden hem niet aan en hij had heimwee naar zijn moeder. Reden voor Kerouac om Parijs weer snel te verlaten, aldus Miles.

In de belangrijkste Kerouac biografie, Kerouac, A Biogaphy van Ann Charters komt dit moment echter niet voor. Volgens Charters, een autoriteit op het gebied van de Beat Generation, bezocht Kerouac Parijs slechts eenmaal, in juni 1965. Geen enkele Beat-auteur verbleef toen nog in de Rue Git-le-Coeur.

Voorouders

Kerouac wilde in Parijs onderzoek doen naar zijn uit Frankrijk afkomstige voorouders. Zijn bezoek werd een aaneenschakeling van teleurstellingen. De eerste nacht spendeert hij 120 dollar bij een bezoek aan een prostituee, de tweede nacht snijdt hij zich per ongeluk aan zijn eigen opengeklapte zakmes, wanneer hij denkt dat enkele ongure types hem achtervolgen. Wanneer hij dronken en bloedend in zijn hotel terugkeert vraagt de eigenaresse hem of hij van plan is snel te vertrekken.

De volgende dag bezoekt hij zijn Franse uitgever Gallimard, maar wordt niet toegelaten omdat de baliemedewerkster bang voor hem is. In de Bibliothèque Nationale krijgt hij te horen dat het archief wat hij wil inzien door de nazi’s is vernietigd.

Hij koopt een vliegticket naar Brest om daar verder onderzoek te kunnen doen, maar mist de vlucht omdat hij in de toiletten de omgeroepen nieuwe vertrektijd niet hoort. Na een urenlange treinreis naar Brest, blijkt dat zijn bagage daar onbereikbaar op het vliegveld staat. Kerouac laat zijn onderzoek maar schieten en keert terug naar Parijs. Daar neemt hij de eerste de beste vlucht naar Florida. Zijn belevenissen leveren in ieder geval nog zijn uiterst vermakelijke reisverslag Satori in Paris op.

Hij koopt een vliegticket naar Brest om daar verder onderzoek te kunnen doen, maar mist de vlucht omdat hij in de toiletten de omgeroepen nieuwe vertrektijd niet hoort. Na een urenlange treinreis naar Brest, blijkt dat zijn bagage daar onbereikbaar op het vliegveld staat. Kerouac laat zijn onderzoek maar schieten en keert terug naar Parijs. Daar neemt hij de eerste de beste vlucht naar Florida. Zijn belevenissen leveren in ieder geval nog zijn uiterst vermakelijke reisverslag Satori in Paris op.

Mythe

Madame Rachou leeft al jaren niet meer. Inmiddels is het Beat Hotel ingrijpend verbouwd, alleen de oorspronkelijke façade is blijven staan. Nu is er het luxe Relais-Hôtel du Vieux Paris gevestigd. Enkele jaren geleden liep ik er eens binnen. Van de gastvrije baliemedewerkster mocht ik even in de foyer rondkijken. Aan de muren hingen foto’s van William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg en Gregory Corso, en ook van Jack Kerouac.

Zo hou je dus een mythe in stand.

Literatuur

Ann Charters, Kerouac, A Biogaphy, San Francisco 1973

Barry Miles, The Beat Hotel, Ginsberg, Burroughs & Corso in Paris 1957-1963,New York 2001

Jack Kerouac, Satori in Paris, New York 1966

Noam Chomsky: Amid Protests And Pandemic, Trump’s Priority Is Protecting Profits

Many years ago, social scientist Bertram Gross saw “friendly fascism” — an insidious authoritarianism that denies democratic rights for corporate ends without the overt appearance of dictatorship — as a possible political future of the United States.

Today, that future has arrived. Donald Trump has not only consolidated the integration between Big Business and government, but now, with the country in the grip of some of the biggest protests in more than half a century, he is actually trying to turn the U.S. into a police state, to “‘dominate’ by violence and terrify any potential opposition,” as Noam Chomsky astutely points out in a new and exclusive interview for Truthout.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, for the past 40 or so years, we have been witnessing in the U.S. the demolition of the welfare state and the supremacy of the ideology of market fundamentalism to the point that the country is unable to deal with a major health crisis, let alone resolve long-standing issues like large-scale poverty, immense economic inequalities, racism and police brutality. Yet, Donald Trump did not hesitate in the midst of the George Floyd protests to declare that, “America is the greatest country in the world,” while he is seeking at one and the same time to start a new civil war in this country through tactics of extreme polarization. Can you comment on the above observations?

Noam Chomsky: I don’t think Trump wants a civil war. Rather, as he says, he wants to “dominate” by violence and terrify any potential opposition. That is his standard reflex. Just look at his outburst when one Republican Senator, Lisa Murkowski, broke strict Party discipline and raised some mild doubts about the magnificence of His Royal Majesty. Or his firing of the scientist in charge of vaccine development when he raised a question about one of Trump’s quack medicines. Or his purge of the inspector generals who might investigate the fetid swamp he’s constructed in Washington.

It’s routine. He’s a radically new phenomenon in American political history.

Another Trump reflex is his call for “the most vicious dogs, and most ominous weapons, I have ever seen” when peaceful protesters appear near his abode. The phrase “vicious dogs” evokes the country’s horror when images of vicious dogs attacking Black demonstrators appeared on the front pages during the civil rights movement. Trump’s use of the phrase was either by intent, to stir up racist violence, or reflexive, arising from his innermost sentiments. I leave it to others to judge which is worse, and what either tells us about the malignancy at the center of global power.

With that qualification, there is no inconsistency. Both the claim that America is the greatest country in the world, in his special sense, and his call for domination, follow from his guiding doctrine: ME!

A direct corollary to the doctrine is that he must satisfy the demands of extreme wealth and corporate power, which tolerate his antics only insofar as he serves their interests abjectly, as he does with admirable consistency in his legislative programs and executive decisions, such as the recent Environmental Protection Agency decision to increase air pollution “in the midst of an unprecedented respiratory pandemic,” risking tens of thousands of deaths, disproportionately Black, the business press reports, but increasing wealth for those who matter.

The success of his tactics was revealed clearly at the January extravaganza at the Davos ski resort, where the masters of the universe, as they are called, meet annually to cavort and congratulate one another. This year’s meeting departed from the norm. There was visible concern about “reputational risk” — recognition that the peasants are coming with their pitchforks. Therefore, there were solemn declarations that, We realize we’ve made mistakes, but we are changing, you can put your faith in us, we will become “soulful corporations,” to borrow the phrase used in accolades to corporate America in the ‘50s.

De vrouw in Nederlandsch Westindië

In 1898 vindt de Nationale Tentoonstelling van Vrouwenarbeid 1898 in Den Haag plaats.

Op 26 juni 1896 richten elf vrouwen in Amersfoort de ‘Vereeniging Nationale Tentoonstelling van Vrouwenarbeid’ op. Hoofddoel is ‘de uitbreiding van de werkkring der vrouw in Nederland’. De dames willen een tentoonstelling organiseren in het jaar waarin Wilhelmina zal worden ingehuldigd als koningin. Voor het eerst een vrouw die de hoogste positie van het land bekleedt, dát feit is van grote betekenis voor vrouwenarbeid! (Bron: deoud-hagenaar.nl)

Historici plaatsen deze tentoonstelling in de eerste feministische golf (1880-1919).

Er verschenen boekjes met tekst en uitleg bij de verschillende onderwerpen van de tentoonstelling.

Dit is er één van: De vrouw in Nederlandsch Westindië. Uitgegeven vanwege de Westindische Rubriekcommissie van de nationale tentoonstelling van vrouwenarbeid. Bijeenverzameld door Jhr. L.C. van Panhuijs. Uitgeverij Becht, Amsterdam. 1898

Het is maar goed dat emancipatiebewegingen hun aard eer aan doen en in staat van permanente revolutie verkeren, zie je als je in het boekje rondbladert.

Lees verder: http://ikkiseiland.com/de-vrouw-in-nederlandsch-westindie/

The Ballet Dance Of The Pita In The Hummus Plate

I begin in the East: East is the crown that Mohamed Abd el-Wahab placed on the head of “Cleopatra.” East is the dust left by a galloping horse on the road between Ras Mohammed and Nuweiba. East is the ballet dance of the pita on the hummus plate. East is a bag of tears hidden in the corridor of Umm Kulthum’s throat. East is Mahmoud Darwish’s suitcase. East is two lines by Omar Khayyam: “Ah could I hide me in my song, To kiss thy lips from which it flows!”. East is the space between ‘tfadl’ (Arabic for “please”) to sahten (Arabic for “well done”) חסרה שורה על סבא סלח . East is Grandmother Haviva’s plate of rice. East is a yellowing picture of palm trees on the banks of the Tigris. East is where the sun rises every day.

Umm Kulthum was the first singer I ever heard. She was the queen of the gramophone at the café on Struma Square. My grandfather had a regular table there, and he took me there every morning. It was a five minute walk from the transit camp on the border of Holon-Bat Yam. He spoke only Arabic. The black box of his memoirs contained the gap between the Tigris and the Euphrates. From time to time, he would turn his head to me and wet my lips with drops of arak. Other children, for example, learned to recognize lions from books or at the zoo. The first lions I saw were the ones printed on the arak bottle labels. My first king of the jungle had a combed mane and it was wet from the drops of the drink, which was well blended with the smell of the jasmine branches that the owner of the café placed in vases on the tables every morning. Umm Kulthum’s voice mingles in my head with the sound of the backgammon dice and the murmurs of the men who whispered every word along with her. Her picture, which hung on the wall, frightened me. She was the great woman from the dreams. Not my dreams. But my grandfather would translate lines from her songs into fractured Hebrew for me and try to fish from my eyes half of the lust that flooded his own.

My friends were in kindergarten back then. They sang Shavuot songs like “Baskets on our Shoulders” and others, which polished the Hebrew in their throats, while I was captivated by the hammering of a woman’s voice that struck a lost, distant love. Later, when she sang: “I accustomed my eyes to watch you/if you do not come one day/ that day will be erased from my life”. I believed secretly that these lines were directed at me, too.

Then I heard other voices, but the ritual of hearing her new song on the first Thursday of every month continued. My parents knew that she was Nasser’s singer, and that he was an enemy, and she would often sing to the Egyptian soldiers in order to sharpen their bayonets, which were aimed at us. But in the face of her magical voice, even reason released its grip.

Umm Kulthum is present in the poems I wrote about her as well as in the sense of power of an entire orchestra that lays out a carpet for her vocal chords. I learned from her how to unravel threads from the same carpet and how to weave poetry from them, association after association. She reminds me that I was born in Baghdad.

I wrote my first poems when I was sixteen and a half years old. The secret drawer was locked. I played basketball then and my coach asked us to shoot fifty baskets every day. When I went to the school’s basketball court, I found Amnon Navot there. We had an agreement. He brought back all the balls that didn’t touch the net, and in return I listened to the poems he recited. Thus, against the soundtrack of the bouncing balls, Amnon recited Avidan, Amichai, Guri, Dor, Ravikovitch, and Wallach, Wieseltier, Horowitz, Penn, Gilboa, Alterman and once even half a story by Kaniuk. In his school bag were poetry books and copies of the journal Achshav. Navot was the engine and I connected the cars of association. “Just a little blood to top off the honey,” he would shout, and since then I have been running on the bridge with the poems running after me.[1] I sent the first poems to David Avidan. He answered immediately, read one of my poems on a radio program, and even called me when my first poem was published in the literary supplement of Ma’ariv (edited by David Giladi). Avidan was, in my eyes, the hard asphalt that paved the “roads that take off slowly.”[2] He was the “cutting and simple fact we have nowhere to go.”[3] He was the poet who had been cut out of the dream journal. The musical scale of his songs reminded me more off a rock and roll stadium than a concert hall.

George, the quiet Beatle

‘De stille Beatle’ werd hij genoemd. De bescheiden Beatle, the quiet one. Omdat hij als jongste altijd in de schaduw stond van John Lennon (the smart Beatle) en Paul McCartney (the cute Beatle), en zelfs van de clown Ringo Starr (the sad Beatle).

Samen waren ze the Liverpool Lads of, in een grap van Ringo, the Siamese Quads (de Siamese vierling; quads is de verkorting van quadruplets, vierling of vierwieler). Maar vooral waren ze the Fab Four.

George Harrison zou daar, toen de groep uiteen gevallen was, met ironie op terugkijken in When we was fab, op zijn solo-cd Cloud Nine (1987), met I am the walrus-violen en andere muzikale Beatles-citaten. Fab is kort voor fabulous, zoals nu nog gebruikt in AbFab voor de Engelse comedy Absolutely Fabulous.

Afgunstig op het grote succes van Britse bands als the Beatles, the Stones en the Kinks in Amerika in de jaren 60 – daar wordt nu nog gesproken over the British invasion – creëerde de platenindustrie aldaar volgens een op the Beatles gebaseerde formule een vergelijkbare groep, the Monkees, inclusief speelse spelfout. Dat werd natuurlijk al gauw the Prefab Four, het geprefabriceerde viertal.

Gijs Scholten van Aschat schreef voor seizoen 2011/2012 het toneelstuk the Prefab Four, over vier voormalige nep-popsterren op leeftijd.

Naar zijn ogenschijnlijk bescheiden rol verwees ook de titel van een biografie, The Quiet One: A Life of George Harrison door Alan Clayson. De mysterieuze Beatle werd hij ook genoemd, maar de mystieke Beatle was toepasselijker geweest, gezien zijn belangstelling voor hindoeïsme, meditatie en sitar.

George Harrison zal vooral herinnerd worden vanwege While my guitar gently weeps (waarover aanstonds meer). De ironie wil, dat die treurende gitaar niet door hemzelf bespeeld werd maar, zoals kenners al lang gehoord hadden, door Eric Clapton. Die werd, om zijn onnavolgbare gitaarspel bij the Yardbirds, in 1963 al bekend als Slowhand, maar verwierf de hoogste eer tijdens zijn periode in John Mayalls Bluesbreakers. In 1966 verscheen op Londense muren de graffito Clapton is God.

Clapton speelde in menige sessie mee, maar vanwege contractuele verplichtingen elders gebeurde dat onder schuilnamen. Aan Harrisons muziek bij de film Wonderwall: the Movie (1969), bijvoorbeeld, deed hij mee als Eddie Clayton.

De hulpvaardigheid was wederzijds en ook Harrison diende zich te bedienen van een alias. Als L’Angelo Misterioso (de mysterieuze engel) droeg hij bij aan Cream, de supergroep van Clapton, Jack Bruce en Ginger Baker. Aan het nummer Badge schreef hij mee, op Never tell your mother she’s out of tune speelde hij gitaar.

(De interactie met Clapton was overigens niet uitsluitend van muzikale aard. Clapton liet zijn oog vallen op Harrisons vrouw Patti Boyd. In 1977 scheidde zij van de Beatle, in 1979 trouwde ze met Slowhand. Op hun receptie verzorgden Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr en George Harrison de muziek.)

In andere pseudoniemen was Harrison minder creatief: op Harry Nilssons Son of Schmilsson heet hij George Harrysong, op It’s like you never left van Dave Mason Son of Harry en op Shankar Family and Friends, een album van zijn sitar-leraar Ravi Shankar, Hari Georgeson. Nog Indiaser oogde zijn alter ego op The place I love van The Splinter: Jai Raj Harisein. Als Hari Georgeson speelde hij ook nog mandoline op It’s my life van Billy Preston, de Amerikaanse toetsenist die vanwege zijn vele sessie-werk op Beatles-lp’s the Fifth Beatle werd genoemd.

De Berchrede fan it Flakke Lân

Fryslân DOK

Fryslân DOK

De Berchrede fan it Flakke Lân.

Tinkers formulearje in perspektyf foar de maatskippij nei de Coronacrisis. Hokker ynsjoggen kinne wy meinimme nei de takomst?

Sjoch bygelyks: De Berchrede fan Theunis Piersma:

https://www.demoanne.nl/de-berchrede-fan-theunis-piersma/

“Sa lang’t ik biolooch bin, al wer 40 jier, libje ik mei it besef dat ús wrâld ekologysk nei de barrebysjes giet. Ik wie my tige bewust dat, lang om let, ek de minsken út rike lannen dat fiele soene. Ik frege my ôf, wat sil ik der sels noch fan meimeitsje? Ik haw my de ôfrûne 20 jier geregeldwei yn ’t fel knypt en my fernuvere dat it eins sa goed giet, dat wy allegearre sa blier en blynwei trochlibje. Fansels, de ‘wanden’ hongen grôtfol mei ‘tekens’, mar wat gie it de measten fan ús dochs goed, wat koene wy lekker en goedkeap de wrâld oer reizgje om sa, nei in ritsje Schiphol en in dei of wat ‘langparkeren’, geregeldwei te ûntsnappen nei plakken mei mear romte en mear lânskip as thús.

No is it dan safier. In krisis as dy fan corona is al withoefaak troch firologen oankundige, mar ynienen komt er ús oer it mad en ynienen liket dat ‘it nei de bliksem gean’ him yn fleanende faasje ûntjout. Soks giet dus net stadich, soks rôlet oer jin hinne! Soks is as de see dy’t nei in dyktrochbraak it doarp ynienen yn it klotsende wetter set.

Ik sit thús, en folgje mei ynhâlden siken it nijs. Ik strún it ynternet ôf op syk nei ferstannich praat. It reint moaie, djippe bespegelingen. Want yn in krisis is neitinke en nij tinken nedich, en it moaie is dat sok frij tinken dan ynienen mei! Miskien wol oanmoedige wurdt. Kin ik dan einliks sizze wat ik op myn hert haw? En soe der no wol lústere wurde?”

Of De berchrede fan Oeds Westerhof:

https://www.demoanne.nl/de-berchrede-fan-oeds-westerhof/

“De flinter is in flearmûs wurden. As in orkaan fljocht it coronafirus oer de wrâld. Wa’t sûn is wurdt siik, wa’t swak is ferstjert. Dat jildt foar minsken en likegoed ek foar bedriuwen. It binne ûnwisse tiden foar elk, behalve dan foar ûnheilsprofeten, wûnderdokters, predikers fan het eind der tijden, synisy, utopisten en oare selskroane keningen fan de wissichheid.

Ik wit net wat dizze coronakrisis foar ús betsjutte sil. Ik ha in krisis fan dizze omfang nea meimakke. Myn gefoel komt it tichtst by de tiid fan Tsjernobyl en de útbraak fan aids. Dat wiene ek fan dy ûnsichtbere meunsters. De ynternasjonale spanning liket wat mear op dy fan 9-11, wylst de ekonomyske panyk wat mear oan de bankekrisis tinken docht. Eins komme al dy dingen gear yn de coronakrisis. Hoe’t it komt, dat witte we net, mar we binne yn gefaar.”