Noam Chomsky

Many years ago, social scientist Bertram Gross saw “friendly fascism” — an insidious authoritarianism that denies democratic rights for corporate ends without the overt appearance of dictatorship — as a possible political future of the United States.

Today, that future has arrived. Donald Trump has not only consolidated the integration between Big Business and government, but now, with the country in the grip of some of the biggest protests in more than half a century, he is actually trying to turn the U.S. into a police state, to “‘dominate’ by violence and terrify any potential opposition,” as Noam Chomsky astutely points out in a new and exclusive interview for Truthout.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, for the past 40 or so years, we have been witnessing in the U.S. the demolition of the welfare state and the supremacy of the ideology of market fundamentalism to the point that the country is unable to deal with a major health crisis, let alone resolve long-standing issues like large-scale poverty, immense economic inequalities, racism and police brutality. Yet, Donald Trump did not hesitate in the midst of the George Floyd protests to declare that, “America is the greatest country in the world,” while he is seeking at one and the same time to start a new civil war in this country through tactics of extreme polarization. Can you comment on the above observations?

Noam Chomsky: I don’t think Trump wants a civil war. Rather, as he says, he wants to “dominate” by violence and terrify any potential opposition. That is his standard reflex. Just look at his outburst when one Republican Senator, Lisa Murkowski, broke strict Party discipline and raised some mild doubts about the magnificence of His Royal Majesty. Or his firing of the scientist in charge of vaccine development when he raised a question about one of Trump’s quack medicines. Or his purge of the inspector generals who might investigate the fetid swamp he’s constructed in Washington.

It’s routine. He’s a radically new phenomenon in American political history.

Another Trump reflex is his call for “the most vicious dogs, and most ominous weapons, I have ever seen” when peaceful protesters appear near his abode. The phrase “vicious dogs” evokes the country’s horror when images of vicious dogs attacking Black demonstrators appeared on the front pages during the civil rights movement. Trump’s use of the phrase was either by intent, to stir up racist violence, or reflexive, arising from his innermost sentiments. I leave it to others to judge which is worse, and what either tells us about the malignancy at the center of global power.

With that qualification, there is no inconsistency. Both the claim that America is the greatest country in the world, in his special sense, and his call for domination, follow from his guiding doctrine: ME!

A direct corollary to the doctrine is that he must satisfy the demands of extreme wealth and corporate power, which tolerate his antics only insofar as he serves their interests abjectly, as he does with admirable consistency in his legislative programs and executive decisions, such as the recent Environmental Protection Agency decision to increase air pollution “in the midst of an unprecedented respiratory pandemic,” risking tens of thousands of deaths, disproportionately Black, the business press reports, but increasing wealth for those who matter.

The success of his tactics was revealed clearly at the January extravaganza at the Davos ski resort, where the masters of the universe, as they are called, meet annually to cavort and congratulate one another. This year’s meeting departed from the norm. There was visible concern about “reputational risk” — recognition that the peasants are coming with their pitchforks. Therefore, there were solemn declarations that, We realize we’ve made mistakes, but we are changing, you can put your faith in us, we will become “soulful corporations,” to borrow the phrase used in accolades to corporate America in the ‘50s.

The keynote address was, of course, handed to Trump, the Godfather. The elegant figures assembled don’t like him. His vulgarity and general brutishness disrupt their preferred image of enlightened humanism. But they gave him rousing applause. Antics aside, he made clear that he understands the bottom line: which pockets have to be stuffed lavishly with more dollars.

Another direct corollary of the guiding doctrine is that the con man in charge must control his voting base while he is stabbing most of them in the back with his actual programs — a difficult feat, which he has so far carried off with much skill. The voting base includes not only avid white supremacists but others in the grip of the fear of “them” that is a core part of the culture — and is of course not without foundation. One consequence of bitter repression is that “they” often resort to crime — that is, the retail crime of the weak, not the wholesale crime of the powerful.

For Trump’s prime constituency of great wealth and corporate power, America is indeed the greatest country in the world. How can one fault a country in which 0.1 percent of the population hold 20 percent of the wealth while the majority try to survive from paycheck to paycheck and CEO compensation has reached 287 times that of workers? And calls for domination by vicious dogs placates much of the voting base.

So, all falls into place.

The actor George Clooney responded with an essay for the Daily Beast to the killing of George Floyd by saying that racism is America’s pandemic, “and in 400 years we’ve yet to find a vaccine.” Why is racism so entrenched and intractable in the United States?

The answer is given by what happened in those 400 years. It’s been reviewed before, but for me at least it’s useful to take a few minutes to think it through again until it becomes deeply ingrained in consciousness. In summary:

The first 250 years created the most vicious system of slavery in human history once the colonies had gained their liberty, the foundation of much of the nation’s wealth. It was unique not only in hideous cruelty but also in that it was based on skin color. That is ineradicable, a curse reaching to future generations. Other minorities were brutally treated, even barred from the country by racist laws (Jews and Italians, the prime target of the 1924 immigration law, which lasted for 40 years, long enough to condemn European Jews to crematoria, and post-war, to ensure that survivors went to Palestine, whatever they might have preferred). But the stigma was not permanent. They could be assimilated and turn to more “acceptable” professions than running Murder, Inc.

Also unique is the fervor of American racism. The “one drop of blood” criterion for the U.S. anti-miscegenation laws that remained on the books until the civil rights movement of the 1960s was so severe that the Nazis rejected it when they were searching for a model for the racist Nuremberg laws — though they did appeal to the American precedent as the only one they could find.

Formal slavery ended in 1865, and a decade of reconstruction offered Black people a taste of freedom, which they used with remarkable effectiveness, given the horrifying legacy. That soon ended. A North-South compact offered southern racists free rein to murder and repress, and to provide a fine workforce for agribusiness and the southern industrial revolution by criminalizing Black life and offering employers a disciplined work force with zero rights. One of the best general books on the post-reconstruction period is called Slavery by Another Name, by Wall Street Journal Atlanta Bureau Chief Douglas Blackmon.

That stain on American history lasted pretty much until WWII, when free labor was needed for war industry. I remember well when Black domestic servants disappeared from middle-class homes. During the great growth period after the war, some opportunities opened for Black Americans, though serious impediments remained. The educational opportunities offered by the GI Bill, a major contribution to the health of the society, were denied to Black people. Home ownership, the basis for wealth for most people, was restricted by federal laws barring Black people from federally funded housing — laws that were hated by the liberals who voted for them, but there was no recourse if there was to be any housing at all, thanks to the iron grip of influential southern Democrats, whose racist passions shifted to the Republicans under Nixon’s southern strategy. By the time these racist laws were withdrawn under pressure of the activism of the ‘60s, the opportunities for many Black Americans were lost. The economy suffered stagflation in the ‘70s and then the hammer blow of neoliberalism, designed to keep the poor and working people in their place, with Black communities as usual the most brutally affected. That assault was compounded by a new wave of criminalization of Black life initiated by the deeply racist Reagan administration. That was amplified by Clinton under the cloak of “I am one of you,” and on to George Floyd.

It’s not hard then to answer the question, at least on one level. At a deeper level, we can ask why the disease is so hard to cure.

It is worth bearing in mind that racism is not unique to the U.S. It has always existed in one form or another, but it was not until the Age of Enlightenment and the imperial conquests that it assumed its contemporary virulence. To see it on display in Europe, it is enough to view the intensive efforts of “civilized” Europeans to keep the victims of centuries of hideous European slaughter and terror from “soiling” their shores. Better that tens of thousands should die in the Mediterranean, fleeing from Libya, the scene of the first post-World War I genocide at the hands of the Italian fascist regime — which, we might recall, was highly praised in the liberal democracies of the West, including the guru of “libertarianism,” Ludwig von Mises, who wrote in 1927 that, “It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aimed at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has for the moment saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history.” (His apologists plead that he only intended for these “best intentions” to be a temporary means to “save civilization”; the Blackshirts could then retire.)

Aside from Trump’s criminal negligence of the spread of COVID-19 and his complete insensitivity to the frustration and anger of the people seeking justice through their street protests against the killing of George Floyd and police brutality generally, the United States does not seem to be well served by its version of federalism.

Federalism in its modern form dates back to the Civil War, which changed the phrase “United States” from plural to singular (in English at least). But the problems with U.S. federalism trace back to the country’s founding, and are becoming very severe. In the late 18th century, the U.S. Constitution was a progressive doctrine in comparative terms, even though it was a “framers’ coup” against popular pressures for democracy, to borrow the title of the fine study by Michael Klarman that is the gold standard for scholarship on the establishment of the Constitution. Even the words “We the people,” however remote from reality, were a serious challenge to the regimes of the day. The challenge was serious enough to evoke the venerable domino theory among the leaders of the day. King George III feared that the example of the American revolution might lead to erosion of the empire. The Tsar and Metternich had similar concerns about “the pernicious doctrines of republicanism and popular self-rule” spread by “the apostles of sedition” in the colonies that had cast off the British yoke.

That was then. By today’s standards, the U.S. political system is so regressive that if the U.S. were to apply for membership in the European Union, it would probably be turned down by the European Court of Justice. The Senate is a travesty of democracy. Wyoming, with 500,000 people, has the same number of senators as California, with 40 million. This extreme perversion of democracy affects the Electoral College as well. The House was carefully designed by Madison with measures to reduce the threat of democracy, but all of that has been effaced by radical gerrymandering and an array of devices, mainly devised by contemporary Republicans, to suppress voting by the wrong people. The powers of the presidency have been constrained by good faith and trust, the way the British Constitution functioned for centuries (now eroding). With a wrecker like Trump in office, backed by a party of trembling cowards, these powers verge on dictatorship, as we are now seeing.

By now a small minority — rural, white, devoutly Christian or evangelical — can run Congress. Furthermore, this is ineradicable. The small states can block a constitutional amendment.

These remarks keep to the formalities of the democratic system, putting aside those whom Adam Smith called “the masters of mankind,” FDR’s “economic royalists.” Smith recognized them to be the “principal architects of policy” in 18th century England, the model of democracy in his day. As he wrote, they made sure that policy served their interests, however “grievous” their impact on the general population. Today, they virtually own the political system, from campaign funding to the overwhelming force of lobbyists and innumerable other devices to keep the government securely in their pocket.

Though their power is immense, it is fragile. Hence the concern at Davos about “reputational risks,” and the statements of top executives that they are mending their ways. They don’t have to read David Hume to learn that since “FORCE is always on the side of the governed, the governors have nothing to support them but opinion,” which can be withdrawn.

The power of the masters is indeed fragile. It can be restricted, even overturned, by a public dedicated to different goals. But that requires organization. Thatcher and Reagan knew what they were doing when they launched the neoliberal era with a sharp attack on labor unions, traditionally the spearhead of struggles for social justice.

Just keeping to the formal democratic system, a serious constitutional crisis is inevitable for structural reasons — and Trump is edging toward it right now. It is a matter of concern in high places committed to the constitutional order. There is no precedent for the denunciation of his call for violent suppression of protest by some of the highest military officers — the two previous chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, his former defense secretary and former chief of staff, the former commander of NATO and U.S. forces in Afghanistan, all top-ranking generals — some of whom went on to eloquent support for the protesters. More important, also without precedent is the remarkable mobilization of whites all over the country to participate in the mass nonviolent protests, braving the serious threat of succumbing to the virus along with some police violence. A poll in the first days of June found 64 percent of American adults were “sympathetic to people who are out protesting right now,” while 27 percent said they were not and 9 percent were unsure.

Where this will lead is anyone’s guess, and more may be coming as a fateful election approaches. It’s hard to determine what is more ominous: another four years for the malignancy to spread its poison, or an electoral loss that Trump will declare illegitimate, refusing to leave the White House, calling on the heavily armed “tough guys” he regularly urges on to defend their “Second Amendment rights” by protecting the self-declared “chosen one,” eyes lifted to heaven.

Is this a wild fantasy? Maybe, maybe not. It’s being discussed in respectable circles. Specialists on the topic have warned that Trump is bringing fascism to the U.S. Personally, I think that gives him too much credit. Fascism is too sophisticated a doctrine for him to grasp. It is, furthermore, a doctrine that is antithetical to his own simplistic conception of how the world should be run: by the masters of the universe, with Trump wielding the wrecking ball at whim. Fascist ideology calls for strict control of the society by the fascist party led by the maximal leader; crucially, control of the compliant business classes. That is almost the opposite of what prevails and what Trump’s limited vision seeks to entrench further. He may advocate fascist tactics, but that’s far from fascism. It resembles more closely a tin-pot dictatorship.

Well-regarded analysts in the mainstream are concerned. One is former CIA analyst Robert Baer, who has had lots of experience in tin-pot dictatorships. In his view,

“If I were a foreign intelligence officer assigned to Washington, I’d ask how close he is to imposing martial law because it looks pretty close to me. I mean, he said he will. He’s preparing for it. He’s got a secretary of defense right now who’s balking. It’s very easy to remove him and put somebody in his place. This president is very insecure. And we’ve watched him go after the FBI and the Department of Justice, and he will go after the Pentagon until he gets the officers in that don’t countermand his orders.… I have never seen this in the United States, never heard since the Civil War.… If I were a foreigner, I would really wonder … what’s happening to American democracy.”

We can remind ourselves of how fateful the coming election is by keeping our eyes on current science — for example, the recent report from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, the main monitor of atmospheric CO2, that levels have not only long surpassed all of human history, but are approaching the highest they have been for 3 million years, when sea levels were 50 to 80 feet higher than they are today.

The coronavirus dip is a statistically insignificant deviation, though it does serve to instruct us that there is still time to avert a cataclysm, though not much.

The countries of the world are seeking to do something to respond, not enough, but at least something. The country that is doing the least is the United States, in the hands of the wrecker-in-chief.

Trump does not waste a minute in his relentless drive to race toward the cliff. His February 2020 budget proposal, while naturally calling for continued defunding of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the midst of a raging pandemic, also called for further subsidies to the fossil fuel industries that are laboring to destroy organized human life. To accelerate the disaster, Trump is using the cover of the pandemic to dismantle “federal regulations designed to protect workers, consumers, investors and the environment,” rescind requirements for factories and power plants to monitor or report missions, waive environmental laws for pipelines and other projects, and instruct “agencies across the government to rescind, modify or simply stop enforcing regulations if they burden the economy.”

The last phrase is a euphemism for interfering with profits. Helping the economy would mean building infrastructure and productive capacity, not pouring funds into keeping stock prices high for the benefit of rich investors and predatory financial capital.

“The White House will seek to make many of those roughly 600 deregulatory actions permanent,” according to a former White House official speaking on the condition of anonymity. Trump’s May 19 proclamation, on which this press account is based, drops enough hints to render the prediction plausible. The heads of all agencies are instructed to “review any regulatory standards they have temporarily rescinded, suspended, modified, or waived” and other actions they have taken, and “determine which, if any, would promote economic recovery if made permanent,” subject to conditions that are meaningless; and to consider an array of actions that “temporarily or permanently” relate to “regulatory standards that may inhibit economic recovery” (emphasis added).

The phrase “economic recovery” has always had a definite meaning in the Trumpian lexicon that there is no need to review.

Trump’s dedication to destroy organized human life in the near future for the sake of short-term profit for his constituency is by far the worst of his crimes, in fact the most extreme crime in human history. It is approached in malignancy only by his systematic dismantling of the arms control regime that has reduced the severe threat of terminal nuclear war; and, concomitantly, his promoting the development of more advanced weapons that enemies can use to destroy us.

Amazingly, none of this enters into current discussion, except at the margins.

In the age of COVID-19, we have seen the sudden return of economic thinking guided however loosely by Keynesian ideas (such as increasing government spending and lowering taxes in order to reboost economic activity, and maintaining a solid welfare state) especially in Western Europe. Is this an indication that neoliberalism is finally on its way out? Or will we see a return to the “normal state of affairs” once the health crisis is over, especially in the United States, where there is significant resistance to the ideas of social democracy?

Like a lot of good questions, this one is virtually impossible to answer. The forces that created the current socioeconomic regime, including the pandemic and the race to self-destruction, are not wasting a moment in their dedication to ensure that the neoliberal disaster persists, indeed in harsher form, with more sophisticated means of surveillance and control. They will succeed unless the general population withdraws consent, makes use of the power that is in the hands of the governed, and becomes organized to create a world that is more humane and just — in fact, survivable.

That requires at the very least constructing a minimal social state. We can see what a difficult step that will be by looking at the liberal commentary on the Sanders campaign: good ideas, but the American people aren’t ready for it. That is an incredible indictment of American society, which, according to this judgment, is not able to rise to what is normal elsewhere: universal health care and free higher education, Sanders’s major planks.

But joining the world should be the least of the objectives for a progressive popular movement. Why should decisions about our lives be transferred from elected representatives, over which people have at least some control, to unaccountable private hands, as neoliberal doctrine dictates? Going further, why should people spend almost all of their waking lives under controls so extreme that Stalin couldn’t have dreamed of them — what is called “having a job”? Work under external command is an attack on fundamental human rights and dignity that had been regarded with contempt from classical Greece and Rome until the 19th century, and was bitterly condemned by working people in the early industrial revolution.

That’s only a bare beginning. A different world is possible, a very different one.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, the political economy of the United States and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published several books and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Croatian, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish. He is the author of Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthoutand collected by Haymarket Books.

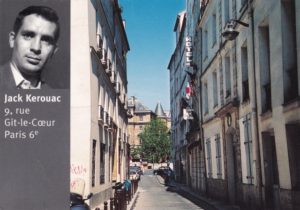

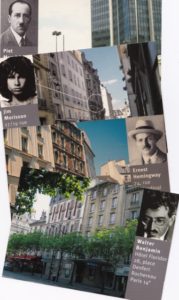

Dit soort ansichtkaarten kun je overal in Parijs kopen. Een foto van een bekende schrijver, pop- of filmster met een foto van het adres waar hij of zij in Parijs gewoond heeft: het adres waar Jim Morrison woonde en stierf (27 Rue de Beautreillis), het hotel waar Walter Benjamin vaak verbleef (Hôtel Floridor) of waar Ernest Hemingway een kamer bewoonde (74 Rue du Cardinal).

Dit soort ansichtkaarten kun je overal in Parijs kopen. Een foto van een bekende schrijver, pop- of filmster met een foto van het adres waar hij of zij in Parijs gewoond heeft: het adres waar Jim Morrison woonde en stierf (27 Rue de Beautreillis), het hotel waar Walter Benjamin vaak verbleef (Hôtel Floridor) of waar Ernest Hemingway een kamer bewoonde (74 Rue du Cardinal). aangeduid, voor korte of langere tijd in een hotelletje in dit straatje. Het naamloze hotel kreeg daardoor later de bijnaam The Beat Hotel. William Burroughs was de meest frequente bewoner van het hotel. Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso en Peter Orlovsky kwamen op bezoek, bleven een paar dagen of woonden er langere tijd.

aangeduid, voor korte of langere tijd in een hotelletje in dit straatje. Het naamloze hotel kreeg daardoor later de bijnaam The Beat Hotel. William Burroughs was de meest frequente bewoner van het hotel. Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso en Peter Orlovsky kwamen op bezoek, bleven een paar dagen of woonden er langere tijd. Dit alles maakte Parijs tot een aantrekkelijke stad voor schrijvers, dichters en kunstenaars. Ook voor diegenen die in hun metier nog geen voet aan de grond hadden gekregen. Beginnend dichter Gregory Corso nam als eerste van de groep Beat-auteurs zijn intrede in het hotel. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs en Peter Orlovsky volgden. Tussen 1957 en 1963 verbleven ze er meerdere malen een paar weken, soms enkele maanden. Voor Burroughs, die dankzij een familietoelage iets ruimer in zijn financiën zat dan de anderen, was Parijs ook een aantrekkelijke tussenstop op weg naar Marokko, waar hij vaak langere tijd verbleef.

Dit alles maakte Parijs tot een aantrekkelijke stad voor schrijvers, dichters en kunstenaars. Ook voor diegenen die in hun metier nog geen voet aan de grond hadden gekregen. Beginnend dichter Gregory Corso nam als eerste van de groep Beat-auteurs zijn intrede in het hotel. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs en Peter Orlovsky volgden. Tussen 1957 en 1963 verbleven ze er meerdere malen een paar weken, soms enkele maanden. Voor Burroughs, die dankzij een familietoelage iets ruimer in zijn financiën zat dan de anderen, was Parijs ook een aantrekkelijke tussenstop op weg naar Marokko, waar hij vaak langere tijd verbleef. Hij koopt een vliegticket naar Brest om daar verder onderzoek te kunnen doen, maar mist de vlucht omdat hij in de toiletten de omgeroepen nieuwe vertrektijd niet hoort. Na een urenlange treinreis naar Brest, blijkt dat zijn bagage daar onbereikbaar op het vliegveld staat. Kerouac laat zijn onderzoek maar schieten en keert terug naar Parijs. Daar neemt hij de eerste de beste vlucht naar Florida. Zijn belevenissen leveren in ieder geval nog zijn uiterst vermakelijke reisverslag Satori in Paris op.

Hij koopt een vliegticket naar Brest om daar verder onderzoek te kunnen doen, maar mist de vlucht omdat hij in de toiletten de omgeroepen nieuwe vertrektijd niet hoort. Na een urenlange treinreis naar Brest, blijkt dat zijn bagage daar onbereikbaar op het vliegveld staat. Kerouac laat zijn onderzoek maar schieten en keert terug naar Parijs. Daar neemt hij de eerste de beste vlucht naar Florida. Zijn belevenissen leveren in ieder geval nog zijn uiterst vermakelijke reisverslag Satori in Paris op.