Riches To Rags To Virtual Riches: The Journey Of Jewish Arab Singers

Some of the most revered musicians from the Arab world moved to Israel in the 1950s and 60s, where they became manual laborers and their art was lost within a generation. Now, with the advent of YouTube, their masterpieces are getting a new lease on life and new generations of Arab youth have come to appreciate their genius. Part one of a musical journey beginning in Israel’s Mizrahi neighborhoods of the 1950s and leading up to the Palestinian singer Mohammed Assaf.

The birth of the Internet awakens our slumbering memory. Sometime in the 1950s and early 1960s, the best artists from the metropolises of the Levant landed on the barren soil of Israel, from: Cairo, Damascus, Marrakesh, Baghdad and Sana’a. Among them were musicians, composers and singers. It didn’t take them long to find themselves without their fancy clothing and on their way to hard physical work in fields and factories. At night they would return to their art to boost morale among the people of their community. Some of the scenes and sounds which at the time would not have been broadcast on the Israeli media have little by little, been uploaded to YouTube in recent years. Through the fall of the virtual wall between us and the Islamic states, we have been exposed to an abundance of footage of great Arab music by the best artists. This development has liberated us from the stranglehold and siege we have been under, allowing us to reconstruct some of the mosaic of our Mizrahi childhood, which has hardly been documented, if at all.

We should remember that in the new country, as power-hungry and culturally deprived as it was in the 1950s and 1960s, the impoverished housing in the slums of the Mizrahi immigrants was a place for extraordinary musical richness. The ugly, Soviet-style cubes emitted a very strong smell of diaspora. At night, the family parties turned the yards, with the wave of a magic wand, into something out of the Bollywood scenes we used to watch in the only movie theater in our neighborhood. On the table, popcorn and a few ‘Nesher‘ beers and juices. At a Yemenite celebration one would be served soup, pita bread, skhug and khat for chewing, and at that of the Iraqis,’ the tables would have kebabs and rice decorated with almonds and raisins. A string of yellow bulbs, as well as a beautiful rug someone had succeeded in bringing from the faraway diaspora, hung between two wooden poles. There were a couple of benches and tables borrowed from the synagogue, and sitting on the chairs, in an exhibit of magnificent play, were the best singers and musicians of the Arab world.

It is worthwhile to reflect upon those rare times, just before the second generation of Mizrahim began trying to dedicate itself to assimilating in the dominant culture. Those were the days when the gold of generations still rolled through the streets of the Mizrahi neighborhoods and through its synagogues. We should step back for a moment and allow ourselves to look at what we had, what was ours, and what ceased to be ours.

An example of the musical paradise in which we lived can be seen in a video recording from a little later – apparently from the early 1990s. At that time, Mizrahi musicians of all origins were already mingling at each other’s parties, which we see here in a clip of a Moroccan chaflah. The clip, uploaded by Mouise Koruchi, does not tell us where and when the event took place. The musicians in this clip are: Iraqi Victor Idda playing the qanun, Alber Elias playing the Ney flute, Egyptian Felix Mizrahi and Arab Salim Niddaf on violin. One of the astonishing singers is the young Mike Koruchi, tapping the duff and singing with a naturalness as if he never left Morocco, a naturalness that our own generation in Israel has lost. Indeed, it turns out that back then he used to visit Israeli frequently but did not actually live there.

Following him, we see some older members of the community appear on the stage: Mouise Koruchi sings ‘Samarah,’ composed by Egyptian singer Karem Mahmoud; after him comes Victor Al Maghribi, the wonderful soul singer also called Petit Salim (after the great Algerian singer Salim Halali); Mordechai Timsit sings and plays the oud; and Petit Armo (father of the famous Israeli singer Kobi Peretz) rounds out the team. This performance could easily be included in the best festivals in the Arab and Western world, complete with Al Maghribi’s beautiful clothes and the rug at the foot of the stage.

Next up, we encounter rare footage of singer Zohra al-Fassia wearing beautifully stylish clothes, recorded in her flat in a public housing project, surrounded by treasures from the Moroccan homeland. The clip demonstrates a little more of the musical beauty and the aesthetic of the small celebrations in the development towns and neighborhoods.

In my neighborhood, which was mostly populated by Yemenites, we enjoyed a regular menu of prayers in angelic voices, drifting away out of the many synagogues in the neighborhood every Shabbat and every holiday. This is a recording from government housing in Ra’anana in 1960 of ‘Yigdal Elohim Chai’ written by Rabbi Daniel Ben Yehuda, the rabbinic judge from Italy. The magnificent and powerful Yemenite tune reflects, to me, more successfully than Sephardic or Ashkenazi ones, the idea of God’s greatness expressed in the 13th century piyut (a Hebrew liturgical poem). At night the sweeping rhythm of the tin drums, the only musical instruments at Yemenite weddings and henna celebrations, called out to summon us. As soon as we heard the drums from afar we, a herd of kids, ran over to participate. Uninvited guests would never be chased away; there were hardly any fences between the houses anyway; the neighborhood felt like one huge courtyard in the middle of our house. And that is exactly the way it sounds in another recording, in the 1960s, of singer-songwriter Aharon Amram, the most important musical figure among Yemenite Jews.

And now, let’s take in the dances of a breathtaking singing and dancing session of Shalom Tsabari of Rosh Ha’ayin, the rhythm virtuoso and one of the greatest Yemenite singers in a late recording of from the late 1980s. (The drums he plays perfectly recall the black music which arrived in the neighborhood in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was then that the children adapted African-American hairstyles, which miraculously suited their curly hair and prayed with intense bodily twists to the Godfather, James Brown).

In a neighborhood where the only television was in the Iraqi café with its antennae tuned to Arab stations, before the arrival of Israeli television and with few record players around, we had the good fortune to watch singers, vocal legends, who people across the Arab world would have done anything just to catch another glimpse of.

In a neighborhood where the only television was in the Iraqi café with its antennae tuned to Arab stations, before the arrival of Israeli television and with few record players around, we had the good fortune to watch singers, vocal legends, who people across the Arab world would have done anything just to catch another glimpse of.

In the next video clip, Najat Salim performs a song from the repertoire of Saleh and Daoud al-Kuwaity. Saleh, who accompanies her on the violin in this scene, is the father of modern Iraqi music and, along with his brother Daoud and other Jewish musicians, kicked off the musical revolution that took place in Iraq in the beginning of the 20th century. These musicians played a significant role in turning the ensembles called ‘Chalrey Baghdad’ into orchestras in the style of new wave Arab music. In this process, which happened in tandem with that of other Arab countries (first and foremost Egypt), western sounds began to inform the traditional Arab sound – with influences ranging from classical music to waltz, rhumba and tango. The revolution was so successful that all Arabs, from the fellah to the metropolitan feinschmecker connected to it with every fiber of their being. The footage was uploaded to the Internet by an Iraqi, who gave it the somewhat naive title, ‘The Star Najat Salim,’ apparently not realizing that Salim was virtually unknown in Israel.

Part of the experience of the Iraqi chafla, which was typical of the home where I grew up, a secular bohemia rooted in the heart of Arab culture, can be heard in the notes of this fabulous violin taksim composed and performed by the violinist Dauod Aqrem in the following clip, smoking and playing simultaneously. The Egyptian Faeiza Rujdi, a fiercely expressive Israeli Broadcasting Authority singer whose songs were a hit in Iraqi chaflas, introduces Aqrem (in the clip, she sings muwashshah, “girdle poems,” which originate in the verse of medieval Andalusia). The next clip features Iraqi maqam singer, poet and composer Filfel Gourgy, accompanied by Saleh al-Kuwaity on violin, with Najat Salim beside him. The clip below shows a royal duet of the mighty Filfel and Najat singing a composition by Mulah Othman al-Musili, the poet, composer and performer of the 19th and early 20th century. Al-Musili was one the founders of the Iraqi maqam and a virtuoso of Turkish-Sufi music. They are accompanied by the Arab Orchestra of the Israeli Broadcasting Authority.

These links demonstrate that it is mostly Arabs who long for Gourgy. The Internet began to break down the barriers of alienation between the Arab public and Jews from Arab countries who immigrated to Israel, but the development came too late. Filfel Gourgy rose to fame only posthumously, and will never know what is written and said about him on Arabic websites today, where he is considered one of the greats among Arab musicians by music experts from academia. Nor will he ever know how often his voice reverberates on Iraqi radio heritage programs for younger generations. Filfel Gourgy did not live to see that young Iraqis who edit small documentaries on YouTube and Facebook sync stills of Old Baghdad in the 30s to his voice, his music symbolizing Baghdad the way Gershwin’s embodies New York.

The maqam artists did not live to witness the 2008 UNESCO resolution that declared Iraqi maqam should be preserved as intangible cultural heritage of humanity. This very same Iraqi maqam was severed from the country the moment the Jews hastily packed it in their suitcases and fled to Israel. Filfel Gourgy, Saleh and Daoud Al-Kuwaity, Ezra Aharon, Ya’acov al-Ammari, Yosef Shem-Tov, Elias Shasha, Salim Shabbat, Yechezkel Katzav, Yusuf Zaarur and many others in the Iraqi Jewish community are displayed on the monumental wall of the Maqam masters.

The maqam artists did not live to witness the 2008 UNESCO resolution that declared Iraqi maqam should be preserved as intangible cultural heritage of humanity. This very same Iraqi maqam was severed from the country the moment the Jews hastily packed it in their suitcases and fled to Israel. Filfel Gourgy, Saleh and Daoud Al-Kuwaity, Ezra Aharon, Ya’acov al-Ammari, Yosef Shem-Tov, Elias Shasha, Salim Shabbat, Yechezkel Katzav, Yusuf Zaarur and many others in the Iraqi Jewish community are displayed on the monumental wall of the Maqam masters.

Meanwhile, all day long at home, the radio was tuned to a variety of Arab stations; therefore we, the children, simultaneously heard childhood songs and lullabies along with Arab children in their own countries. Twice a day, a dish was served which featured an Umm Kulthum concert as its main ingredient. And the rest of the day, we would hear Abd al-Wahhab, Abdel Halim Hafez, Farid Ismehan, Fairuz, Sabah Fakhri, Wadih El-Safi and all the rest. We watched Arabic movies on Arab TV, as well as cabaret performances and charming Arabic operettas in local cinemas, way before Israeli television started to broadcast programs in Arabic. Here is Ya Warda, the cabaret song of Zohra Al Fassia, a song that touches the very core of the secular culture of the Arab Jews.

Thanks to the record shop of the ‘Azzoulai Brothers’ in Jaffa, the neighborhoods and the development towns could hear the singing of the musical genius Salim Halali, an Algerian Jew who, after immigrating to France managed to escape the Nazis. Later he became the idol of Algerian rai singers.

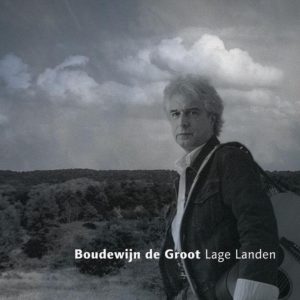

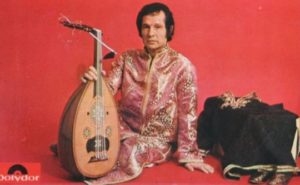

This refined man, composer, singer and poet alike, a Jewish homosexual who sang in Arabic in the land of the French, weaved different cultures into his singing: Andalusian, Berber and Arab. The following clip gives a short summary of the man and his achievements. Look at his fancy gala dresses in the few pictures that highlight his songs. He is all beauty, elegance and cosmopolitanism – features that the Israeli nouveau richehas always craved. Halali performed in Haifa in the 1960s and in the Tel Aviv Sports Hall in 1974, without any mention in the Israeli media. Thanks to Mouis Karuchi, we have the whole recording of the performance in Tel- Aviv in two parts.

We might examine more closely the odd reversal that occurred in Israel in the life of the Jewish Arabs compared to their brothers, the Jewish artists from Russia. The latter arrived over a century ago from their oppressive country to the United States, and were actually quite fortunate in gaining worldwide acclaim. If the Russian artists experienced the American dream of ‘rags to riches,’ then the experience of Arab Jewish artists in Israel was the reverse: ”from riches to rags.”

We might examine more closely the odd reversal that occurred in Israel in the life of the Jewish Arabs compared to their brothers, the Jewish artists from Russia. The latter arrived over a century ago from their oppressive country to the United States, and were actually quite fortunate in gaining worldwide acclaim. If the Russian artists experienced the American dream of ‘rags to riches,’ then the experience of Arab Jewish artists in Israel was the reverse: ”from riches to rags.”

When we say, “what once was is no more,” about the Diaspora musicians who arrived in Israel, the intention is not nostalgic. It simply communicates that these great musicians had no Jewish successors. The next generation was hardly able to master the art and language of their parents. Of all the important musicians only a few played in the Arab Orchestra of the Israeli Broadcasting Authority. For instance, Alber Elias, Zuzu Musa from Egypt or qanun player Abraham Salman. It was renowned violinist Yehudi Menuhin who kissed Salman’s hands, fully recognizing his genius. Those are fine examples of artists who learned music in schools and academies. Yet that sort of musical education was not available in Israel.

The students of artists such as Yosef Shem Tov were in fact Palestinians, whose elite, including Palestinian musicians, was uprooted from their homeland in 1948. There were not many Jews like the musician Yair Dalal who took the trouble to come and learn from masters such as Salim al-Nur. Al-Nur composed pieces of intellectual and emotional complexity. But on YouTube, a melody he composed at the age of 17 in Iraq, ‘Oh You Bartender,’ attracted many listeners in the Arab world: it was sung by Jewish singer Salima Murad, the national singer of Iraq, and the words were written by the poet and caliph of the house of Abbas, Ibn Al-Mu’tazz of the 9th century.

Salim Halali. He is all beauty, elegance and cosmopolitanism – features that the Israeli nouveau riche has always craved.

Hand in hand with the erasure of the active role of the Jews (sometimes as an avant-garde) in the creation of modern Arabic music, the number of Jewish listeners has declined. In the first Mizrahi immigrant generation, those in the Mizrahi Jewish community still completely understood both the palimpsest of this high musical language that was developed, layer by layer, over generations and the musical talent of the geniuses of their generation. They continued to consume this music over the entire course of their lives. High art and popular culture were not considered separate entities. Everyone was a connoisseur. As the years went by, the audience grew older. The young generation turned to ‘Hebrew’ music and was asked to abandon its roots. According to the conventions of Arab culture, an artist needs an audience that can understand what he (or she) sings about, and that would discern the beauty in the musical phrasing he sings or plays. She needs this sigh of pleasure and wonder: ‘aha’ or ‘alla.’ Without this feedback, he cannot sing and play. This sudden breach in a naturally developing culture was the reason our musical heritage died.

Logging in to Arab cyberspace, when entering the names of those forgotten artists in Arabic, we will find out that their names are cherished by musicologists on musical forums, in discussions on Iraqi television and radio, and in audio and video clips uploaded by Arab internet users. The acceptance of and excitement over the best of our artists evokes sad thoughts of those who were supposed to be our brothers in Israel.

In Israel, the conversation of the greatness of these musicians has become strange. How is it possible to describe that which is no longer apparent? Many of the youth in Israel no longer understand profoundly the beauty of the sound in the manner of their parents and grandparents and the current young generation of Arabs. One can always praise and exalt, yet she who has Arabic music for breakfast, without saying a word, already knows that Salim Halali and Filfel Gourgy reach great heights. Of course it is possible to talk about the past status of the distinguished musicians and to bring historical evidence to their detractors, that Saleh al-Kuwaity and Zohra al-Fasia were the artists of the king. Yet this is a defensive discourse. After all, the essence of our tragedy is not that al-Fasia does not have a king to sing to. The problem is that she has no one to sing to.

And this is what Salim Halali sings about in “Ghorbati” (my Alienage), a beautiful lamentation about the exile of the eternal wanderer in the places of others (loosely translated): “I, who was silver, turned into copper and the garment I was wearing left me naked. I, who gave advice to the others, now have lost my mind, my wisdom turned to madness.

—

Read part two of this article here

This post by Shoshana Gabay was taken partly from a movie synopsis she wrote a few years ago about Filfel Gourgy, which was rejected by the Israeli Film Fund. It originally appeared in Hebrew on Haokets.

Translated by Benno Karkabe, Noa Bar and Orna Meir-Stacey