Prof.dr. Gerald Epstein

Public education in the U.S. has been under severe attack for many years now, thanks to the dominance of neoliberal thinking and policies across the societal spectrum. However, the coronavirus pandemic has sparked a new crisis in the nation’s public education system as a result of having created huge holes in school budgets, especially in high-poverty areas. Yet, there are ways to prevent the collapse of the public education system in the U.S., if there is a will to do so. And the rescue can come directly through the power of the Federal Reserve, according to leading progressive economist Gerald Epstein, professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Epstein discusses how the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated funding deficits for public education and how the Federal Reserve can step in to save schools.

C.J. Polychroniou: Is the crisis facing public education systems today simply a question of the fall-off in tax revenues on account of the pandemic?

Gerald Epstein: The shortfall is not due only to the fall-off in revenues, though that is a significant part of it. It is also because of the large extra costs that schools and universities will face to operate safely in the COVID world: the extra spacing, cleaning, masks, technology needs, and so on. No one knows exactly how much these extra costs will amount to, but various organizations have estimated them to be somewhere between $116 billion and $245 billion.

These immediate problems are made immeasurably worse in many school districts and for many colleges because of longstanding funding shortfalls facing public education, K-12 and higher education. Many school systems — and especially those in poor communities, communities of color and rural communities — have been faced with serious cut-backs for more than a decade, punctuated, only occasionally and inadequately, with compensating increases.

Indeed, since the 2007-08 Great Recession, states have been devoting even less money to public education. Is this because of the peculiarities of the current model of education, which essentially leaves matters of funding education largely to the states, or because of the domination of neoliberalism at the federal and state levels?

It is true that public education funding in the U.S. comes primarily from the states and local governments. For example, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, in 2016, 47 percent of K-12 funding came from the states, 45 percent from local governments, and only 8 percent from the federal government.

This dependence on states and local governments does contribute to inequalities in school funding among states. But, to get to your question about neoliberalism, the neoliberal turn of state governments, led primarily by Republicans, has had a devastating effect on school funding, especially for poorer communities and communities of color. As Gordon Lafer shows in his brilliant book The One Percent Solution, state and local networks funded by the Koch brothers and others were able to elect state and local officials committed to a litany of neoliberal attacks on unions, public and social goods, and the state, all in the interests of corporations. The result in many states was a cut in taxes and education funding, and a push to privatize education through charter schools and similar tricks. There was also an attack on teachers’ unions and public-school teachers’ pay.

These anti-public school measures were greatly exacerbated by the fallout from the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 (GFC), which itself was largely due to neoliberal policies of financial deregulation (which exacerbated long-growing deeper problems in the economy that we have no time to discuss here).

Most states cut school funding severely when the GFC hit; and despite the long (but slow) economic expansion that occurred after the GFC and ended with the pandemic, state funding per student remains below pre-crisis levels. This is especially true of states that cut deeply during the crisis. At the local level, the collapse of the housing market led to a decline in property values in many communities. Since the primary source of local funds for public schools are property taxes, this led to lower local revenues for education. The federal government did increase funding for the states temporarily, but it was not enough and it did not last.

Just prior to the pandemic, some states had finally recovered much of the lost ground in educational expenditures, but many teacher salaries, which had been deeply cut over the neoliberal period, remained below their previous levels and were falling behind wage growth in other professions. In response, there have been a number of teachers’ strikes across the country, where teachers have demanded not only an increase in their pay, but also an increase in funding for their schools. Many of these have been successful.

Similar forces played out with respect to funding of public higher education. State funding of public higher education declined significantly over the last 20 years or more, and students and their families were more and more saddled with the bills. The huge rise in student debt, more than $1.6 trillion worth, is wreaking havoc on a generation of students that has now been confronted with two near-depression level meltdowns in the course of little more than a decade.

The important point is that all these problems were there prior to the onset of the pandemic. Now they have been greatly exacerbated.

You have come up with a proposal to use the Federal Reserve to rescue public education in the U.S., called the Federal Reserve Public Education Finance Facility. Can you briefly explain what it would do?

The motivation for my proposal is that public education — K-12 and public higher education — is facing massive financial shortfalls from the COVID crisis on top of all the financial problems many institutions had been facing even before the crisis hit. The Republican-controlled Senate under the leadership of Mitch McConnell has expressed very little support for giving states and local governments the help they need. In fact, in the Senate Republican bill that was released on July 28, there is basically no funding for state and local governments, whereas the HEROES Act had $1 trillion earmarked, and only $105 billion for K-12 and higher education. Even if this gets increased through negotiation with Democrats, it is unlikely to fill the holes in the public education budget.

Knowing this, political scientist Dean Robinson — a colleague of mine who is on the National Education Association and on the board of directors of the Massachusetts Teachers Association — told me he is concerned that direct federal stimulus is falling far short of requirements, especially for the public sector, given that the Republican-led Senate can curtail whatever the Democratic-led House offers by way of a package (this has been borne out). Given the historic intervention that the Fed is making with respect to private debt, he said he wonders whether we could reimagine a type of bond under the Fed’s expanded facilities.

I told him I would look into this question. And the short answer is yes. There is a lot the Fed is already doing for Wall Street and corporate bond holders, hedge funds and private equity firms. If the Fed can do all that, then there is certainly a lot more it could do for students and teachers who are likely to find themselves in deep austerity mode.

So, first, some background: The Federal Reserve, the United States’ central bank, has promised to provide a huge amount of credit — “whatever it takes” as Jerome Powell, the Fed’s chair, put it — to keep the U.S. economy afloat through the national emergency of the COVID-19 crisis. This pledge follows by just a decade the massive amount of credit the Federal Reserve provided during the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 to avoid a global financial meltdown. In that episode, the Fed used the money to mostly bail out mega-financial institutions like Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Wells Fargo and AIG, whose very actions had caused the meltdown in the first place. The estimates for the amount of credit provided run from $12-22 trillion. Virtually none of this was provided to workers, small businesses or homeowners who were about to lose their homes.

This time around, when funds were being appropriated in Congress under the CARES Act to underwrite special Federal Reserve financial support for the economy, congressional Democrats, unions and other pro-worker organizations lobbied to make sure that some of that Federal Reserve money would be allocated to small business and workers. At the same time, they made sure that funds would be available to states and local governments that would be facing catastrophic losses in revenue from the crisis.

The result of this labor union and Democratic pressure was the creation of a Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) whose purpose is to help support state and local government borrowing so they can provide important services, including public education, during the crisis. The U.S. Treasury seeded this facility with $35 billion in capital. On this basis, the Federal Reserve has the capacity to lend out up to $450 billion to state and local governments.

Unfortunately, only one state, Illinois, has borrowed from this facility so far. The lion’s share of the funds is just sitting there, unused.

Why? The answer is that the Fed put so many restrictions on the use of funds and made them so expensive, that the other states and municipalities are finding they cannot benefit from the funds, even while many of them are in the process of planning massive cuts to programs, including education.

There are three constraints here. One is how long the funds can be borrowed for (the term). The maximum length of time for which funds can be borrowed is three years. This is shorter than the terms for other Fed credit actions — some are five years, some are indefinite (i.e., permanent). Three years are not enough for states, municipal borrowers and school districts to get through the crisis without devastating cuts and then find the funds to repay the loan from the Fed (or to find some financial institutions to buy the debt at a reasonable cost). A much longer maximum available term will be necessary to make this useful — 5 to 10 years.

Second, the cost of borrowing is way too high. The Fed evidently wanted their facility to be used only as a last resort and they succeeded all too well. The Fed is charging 3, 4, 5 percent interest rates when interest rates on federal government short-term debt is close to zero. The Fed should lower the cost of borrowing for states and municipal governments from this facility much closer to the Fed’s policy rate, which is close to zero.

Some progressive Democrats and pro-worker organizations such as unions were able to get these improvements into the follow up “stimulus bill,” the HEROES Act. These provisions passed but now the bill is blocked because the Senate is refusing to take it up.

A third problem centers on how the states borrow. Most states must balance their “current” budgets, year to year. Current budgets reflect year-to-year costs like wages, services, and so forth. On the other hand, most states are allowed to borrow on their “capital” budgets for longer-term investment, such as building bridges, highways and school buildings. These capital budgets have limits of course, but they are less binding than the requirement to balance the current budget year by year. In this situation, most states limit very severely the degree to which they can borrow to pay teacher salaries and other educational expenses.

Is there a fix for this problem? In my proposal, I suggest that states and school districts issue “Human Capital Bonds” to pay teachers’ salaries and other current educational expenses. Economists have long recognized that among its other important benefits, education represents a long-term investment in developing a human’s capacities for achievement. This is a creation of “capital,” using mainstream economists’ term for it, that has long-term payoffs for not only that individual but for society as a whole. At least a portion of such expenditures, especially in a crisis such as this, can and should be put under the capital budgets of states and state authorities.

Purchasing of these bonds by the Federal Reserve would give a legitimacy and stamp of approval to these new financial instruments, and would make it much more likely that these would receive a good credit rating and not harm the overall credit rating facing the state, a prospect that deeply worries state treasurers and politicians.

What other institutions and interests that will be competing for access to these funds? How could we ensure that public education receives its proper due in a country where neoliberalism still reigns supreme?

First of all, this competition among various constituencies in states and municipalities for budget expenditures, and then also for Federal Reserve funds, is a natural part of the political process. There are many critical needs emerging in this massive pandemic economy, which has greatly worsened pre-existing inequalities and accumulated disinvestment and failings.

But borrowing from the state and municipal bond markets is one that is especially foreign to public education, apart from building schools and dorms and gyms. Even if the states were to borrow from the Fed facility, public education, a newcomer in this field, is likely to get substantially crowded out by the big infrastructure, development and medical operators who are experienced in this space.

That is one of the reasons I proposed a special Fed facility just for funding public education: The Federal Reserve Public Education Emergency Finance Facility. This facility would dedicate Federal Reserve funds to lending money for public education to states, municipalities and school districts, at low interest rates and long terms. It would be a welcome buyer of human capital bonds from states that want to issue them to fund education during this crisis. This way, public education would not have to compete with the big and experienced capital market borrowing state, municipal developers and other borrowers.

In your view, how would you assess the chances of your proposal rescuing public education in the post-COVID era?

Well, I hope it is not needed. It would be far better to have the federal and state governments properly fund public education. In the current crisis, it would be much better to have the federal government give billions of dollars of budget support for state and local governments to fund necessary services and investments, such as public education.

But if there is not enough federal aid forthcoming, then a plan B is necessary to prevent a near collapse of our public education system. I think there is a decent chance that through the active work of unions and Democratic congressional leaders, the Federal Reserve will eventually loosen up its requirements and make funds more available for state and local support, including for education. We must try to organize and lobby the Federal Reserve and, more specifically, the Regional Federal Reserve Banks, 12 all over the country, to loosen their restrictions and lower the costs of credit for states and municipalities, and to make the credit longer term. This is what they are doing for banks and hedge funds. They should end or cut way back on their support for Wall Street and, instead, help the public, the workers and unemployed and core social functions like public education. The money is there! It has already been set aside by the Federal Reserve. And they can easily create more in this era of high unemployment and rock-bottom interest rates. What are they waiting for? We have to make them use it, and use it to serve the needs of the people, and not the banks.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, the political economy of the United States and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published several books and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Croatian, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish. He is the author of Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthoutand collected by Haymarket Books.

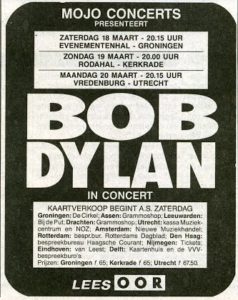

Zo schrijft de een over een optreden van Paul Simon in Haarlem, schrijft een ander over Bob Dylan die niet in Haarlem optrad en word je gewezen op het verhaal van Herman Sandman over een fietsende Dylan in het noorden van Groningen

Zo schrijft de een over een optreden van Paul Simon in Haarlem, schrijft een ander over Bob Dylan die niet in Haarlem optrad en word je gewezen op het verhaal van Herman Sandman over een fietsende Dylan in het noorden van Groningen