The US Chose Endless War Over Pandemic Preparedness. Now We See The Effects

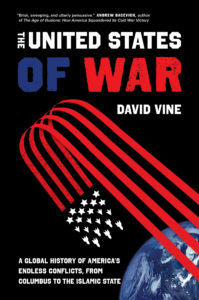

The United States of War – A Global History of America’s Endless Conflicts, from Columbus to the Islamic State. ISBN: 9780520300873

The United States has the longest record of war-fighting in modern history. Why that is the case is not a question that has an easy answer; suffice to say, however, that militarism and violence run like a red thread throughout U.S. political history, with enormous costs both for the domestic economy and the world at large, as a recently published book by David Vine makes plainly clear. In fact, the militarist mentality is strongly reinforced by the Trump administration in spite of the fact that the current president claims to have an aversion to “endless wars.” In this exclusive Truthout interview, Vine, a professor of anthropology at American University in Washington, D.C., addresses critical questions about U.S. war culture and Trump’s own contribution to the violence that has always been foundational to U.S. culture.

C.J. Polychroniou: Your latest book, The United States of War: A Global History of America’s Endless Conflicts, from Columbus to the Islamic State, is a detailed survey of the U.S.’s obsession with militarism and war. Have you come to a definite conclusion or explanation as to why the United States has been at war for about 225 of the 243 years since its independence?

David Vine: There is, of course, no simple answer to this incredibly important question. According to my research, the U.S. military has been at war or engaged in other combat in all but 11 years of U.S. history — 95 percent of the years the United States has existed. My book shows how the huge collection of U.S. military bases abroad provides a key — or a kind of lens — to help understand why the United States has been fighting almost without pause since 1776. Bases abroad, bases beyond U.S. borders show how U.S. political, economic and military leaders — shaped by the forces of history, capitalism, racism, patriarchy, nationalism and religion — have used taxpayer money to build a self-perpetuating system of permanent, imperialist war revolving around an often-expanding collection of extraterritorial military bases. These bases have expanded the boundaries of the United States, while keeping the country locked in a state of nearly continuous war that has largely served the economic and political interests of elites and left tens of millions dead, wounded and displaced.

To be clear, my argument is not that U.S. bases abroad are the singular cause of this near-endless fighting. Indeed, my book shows how the answer to why the U.S. government has fought so constantly lies in the capitalist profit-making desires of businesses and elites, in the electoral interests of politicians, and in the forces of racism, militarized masculinity, nationalism and missionary Christianity, among other dynamics.

U.S. bases abroad, however, have played a key and long overlooked role in the pattern of near-constant U.S. fighting: that is, since independence, bases that U.S. leaders have built beyond the borders of the United States not only have enabled wars but also have made offensive imperialist wars more likely. While U.S. leaders often portray bases abroad as defensive in nature, the opposite is generally the case: bases built on the territory of other peoples have tended to be offensive in nature, providing a launchpad for yet more wars. This has tended to create a pattern in which bases abroad have led to wars that have led to the construction of new bases abroad that have led to new wars that have led to new bases and so on.

Can you offer us a quick assessment of the overall costs of the “global war on terror?”

It’s impossible to capture the immensity of the catastrophe that the so-called “global war on terror” has inflicted. Around 15,000 U.S. military personnel and contractors have died in wars the U.S. government has waged since invading Afghanistan in October 2001. Hundreds of thousands of troops have returned with amputations, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injuries, and other physical and mental damage. As of 2018, 1.7 million veterans had reported a wartime disability.

Across the countries where the U.S. military has fought, the death toll is at least 50 times higher than the U.S. death toll: In Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Pakistan and Yemen alone, an estimated 755,000 to 786,000 civilians and combatants have died as a result of combat. Total deaths may reach 3.1-4 million or more, including those who have died as a result of disease, hunger and malnutrition caused by the wars. Entire neighborhoods, cities and societies have been shattered by these wars. The number injured and traumatized surely extends into the tens of millions. At least 37 million people have been displaced from their homes during U.S. fighting in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, the Philippines, Somalia, Syria and Yemen. For perspective, 37 million is about as many people as live in California and in Texas and Virginia combined. Thirty seven million displaced is more than those displaced by any war anywhere in the world since at least 1900, with the exception of World War II.

The U.S. government and the United States as a country are not single-handedly responsible for all the death, displacement and destruction of these wars. Other governments and combatants also bear significant responsibility. However, the U.S. government bears disproportionate responsibility, especially for the wars it has launched (Afghanistan, the overlapping war in Pakistan, and Iraq), the wars it has escalated (Libya and Syria), and the wars in which U.S. forces have been significant combatants (Yemen, Somalia and the Philippines). Alongside U.S. funding for and involvement in combat in a total of at least 24 countries since 2001, the rhetoric of the “war on terror” alone has also fueled wars and violence worldwide.

Alongside the human damage, the financial costs of the so-called war on terror are so large, they’re nearly incomprehensible. As of October 2020, the U.S. government has spent or obligated a minimum of $6.4 trillion on the post-2001 wars, including the costs of future veterans’ benefits and interest payments on the money borrowed to pay for the wars. The actual costs are likely to run hundreds of billions or trillions more, depending on when we force our politicians to bring these seemingly endless wars to an end.

While it’s incredibly hard to fathom $6.4 trillion in taxpayer funds vanished, the catastrophe is compounded when we consider how else the U.S. government could have spent such incredible sums of money. What could these trillions have done to provide universal health care, to rebuild public schools, to build affordable housing, to end homelessness and hunger, to rebuild crumbling civilian infrastructure, to prepare for pandemics? In addition to the 3-4 million who have likely died in the wars the U.S. government has fought since 2001, how many more have died because of the investments the U.S. government did not make? These are questions that, I have to say, should make us weep.

In trying to wrap our minds around the unbelievable human and financial costs of the so-called “war on terror,” we also have to remember that this war has also been a catastrophic failure on its own terms: the main result of the “war on terror” has been to spread terror and dramatically expand the number of groups and people who would engage in terrorist attacks on U.S. citizens and others civilians worldwide as a political tool. In Afghanistan, for example, there are at least 10 times as many militant groups today as there were in 2001. Meanwhile, research has consistently shown that military action is rarely effective in shutting down militant “terrorist” groups. Responding to the attacks of 9/11 with what has now been an endless global war has been one of the most catastrophic and deadly mistakes in world history.

Esreteip

In antwoord op de vraag naar de opmerkelijkste naam in de Nederlandse literatuur zou het werk van Bordewijk ongetwijfeld vaak genoemd worden. Alleen Bint (1934) al biedt een hele rij memorabele namen, zoals Whimpysinger, Van der Karbargenbonk en Taas Daamde, Surdie Finnis, Schattenkeinder, Bolmikolke, Klotterbooke en Kiekertak, namen die hij overigens gewoon in het telefoonboek van Rotterdam gevonden had. Of Karakter (1938), met zijn namen van gewapend beton: Dreverhaven, Katadreuffe en Kalvelage.

In antwoord op de vraag naar de opmerkelijkste naam in de Nederlandse literatuur zou het werk van Bordewijk ongetwijfeld vaak genoemd worden. Alleen Bint (1934) al biedt een hele rij memorabele namen, zoals Whimpysinger, Van der Karbargenbonk en Taas Daamde, Surdie Finnis, Schattenkeinder, Bolmikolke, Klotterbooke en Kiekertak, namen die hij overigens gewoon in het telefoonboek van Rotterdam gevonden had. Of Karakter (1938), met zijn namen van gewapend beton: Dreverhaven, Katadreuffe en Kalvelage.

Hoog op mijn lijst zou Inigo Wintrop staan, de hoofdfiguur in Cees Nootebooms roman Rituelen (1980). Een intrigerende naam: welluidend, ongebruikelijk, on-Nederlands en toch ook niet gemakkelijk aan een andere taal te verbinden. Zijn roepnaam – Inni – is een palindroom. Maar hij zou niet op de eerste plaats staan. Die is voor Esreteip. Niet zozeer omdat dat de merkwaardigste, onbegrijpelijkste, vreemdste of gewrongenste is, maar omdat die naam in slechts acht letters een paar eeuwen cultuurpolitiek, koloniaal beleid en calvinistische hypocrisie oproept.

Het was algemeen bekend dat veel van de heren die in “Nederlandsch-Indië” het vaderlands gezag vertegenwoordigden, er een of meer inlandse vrouw(en) op na hielden: een bijzit, een snaar, een njai. Het was evenzeer bekend dat uit zulke relaties vaak kinderen voortkwamen. Nu waren de Nederlandse verwekkers meestal niet zeer geneigd hun snaar te trouwen of, als ze zelf al deugdzaam, dat wil zeggen met een Nederlandse vrouw, getrouwd waren, het kind als het hunne te erkennen. Maar wel ontstond de gewoonte om de bloedband met het kind aan te geven, zeker als het een jongen was. Dat gebeurde vaak door het kind bij de Burgerlijke Stand te laten inschrijven, niet onder de naam van de vader maar onder de omgekeerde versie daarvan. Zo ontstonden bijvoorbeeld de naam Redlum, Reyem of Rhemrev. En Esreteip.

Dat verschijnsel is onomwonden vastgelegd in het werk van de chroniqueur van Nederlands-Indië bij uitstek, P.A. Daum (1850-1898). Twee duidelijke voorbeelden zijn te vinden in de roman Nummer Elf (1895). Op bladzijde 8 wordt een jonge Indo-vrouw geïntroduceerd:

Er ging een deur open, en om de hoek keek een mooi donker kopje met een overvloed van donkere krulletjes op het voorhoofd, grote schitterende zwarte ogen, en een vrolijk lachende mond met parelwitte tanden. ’t Was Ypsilante Nesnaj wier militaire vader haar zijn omgekeerde geslachtsnaam had gegeven en de malle voornaam, die hij had gelezen in een boek over een Griekse prins.

Twee pagina’s verder richt de Nederlandse hoofdpersoon, Vermey, zich tot een klerk ofwel, in Daums woorden, ‘een kopiist’:

Hij liet een kopiist roepen, een broodmagere, grauwbruine jongeman; een dier Indo-europeanen die nooit transpireren en altijd koude handen hebben, maar meestal slim genoeg zijn.

‘Esreteip,’ zei Vermey (’s mans grootvader had Pieterse geheten), je weet dat het vandaag de veertiende is.’

‘Ja meneer’.

Dat Daum deze namen gebruikt en er ter plekke een toelichting bij geeft, illustreert dat daarmee geen grote geheimen verklapt worden. Iedereen wist dat het gebeurde, iedereen kende er in eigen familie- of vriendenkring voorbeelden van, maar er hardop over praten deed men niet.

De naam Esreteip bestaat overigens wel degelijk: een aantal kabinetten geleden, bijvoorbeeld, kende Suriname een minister Esreteip. Waarmee tevens geïllustreerd is, dat dit gebruik niet alleen in Oost-Indië, maar ook in Suriname en op de Nederlandse Antillen voorgekomen zal zijn.

Soms leende een naam zich nog slechter voor omdraaiing dan Vermehr of Pieterse. Als het resultaat echt onuitspreekbaar dreigde te worden, kon er nog altijd een anagram van gemaakt worden: Sermham uit Harmsen of Served uit De Vries. Of het eerste stukje werd er achteraan geplakt: datzelfde De Vries werd dan Vriesde, een naam die in het betaald voetbal (bij F.C. Den Haag speelden twee broers met die naam) en in de damesatletiek (bij de Surinaamse atlete Laetitia Vriesde) was aan te treffen.

Een nog indirectere vorm van erkenning was het kind opzadelen met de naam van de plaats waar de vader vandaan kwam, maar ook dan in omgekeerde vorm. Het telefoonboek van Amsterdam telde lange tijd nog steeds twee nummers op de naam Madretsma. Ook Madrettor bestaat.

De groei van deze groep namen werd ook beïnvloed door de dragers van die namen zelf.

Generaties lang hadden Nederlandse vaders hun trots over hun bij een bijzit verwekt nageslacht geuit in een omdraaiing van de feiten, maar de kinderen zelf wensten er soms zelf ook wel iets in te zeggen hebben. Zij hadden niet iets te verbergen, integendeel, zij waren deels van Europese afkomst en waren daar trots op. En om dat te laten blijken, draaiden zij hun naam weer om en voegden die toe aan wat er al stond. Riemer Reinsma geeft in zijn boekje Aangenaam. Mag ik mij voorstellen? (Amsterdam, 1986) de voorbeelden Redlod van Dolder en Satoor de Rootas.

Wellicht vleit u zich met de gedachte dat het u onmiddellijk zou opvallen als u een zo opmerkelijke naam als Madretsma of Esreteip onder ogen zou krijgen. Maar ons waarnemingsvermogen heeft een flinke marge ingebouwd en iets moet er wel heel erg uitspringen, willen wij het als afwijking van een norm opmerken. Vrijwel dagelijks komen we namen tegen (althans, kunnen we namen tegenkomen) die volgens het hierboven beschreven procédé ontstaan zijn.

In de zo mediterraan ogende achternaam van Jack Gadella, tekstschrijver van een aantal nummers voor ‘Kinderen voor kinderen’, vinden we het woord ‘alledag’ terug. De Vlaamse actrice Alida Neslo is van Surinaamse afkomst. ‘Olsen’ klinkt weliswaar Scandinavisch maar is wel een veel logischer volgorde van letters dan Neslo. De naam van Surinames eerste Olympisch en wereldkampioen zwemmen, Anthony Nesty, heeft eenzelfde constructie. Een bekend Nederlands jazzmuzicus is Rob Essed, een Volkskrant-redactrice heet Yvonne van Gnirrep .

Een koloniaal verleden leeft niet alleen voort in de geschiedenisboeken en in het slechte geweten van een natie, maar ook in de kleine details van alledag.

Voor wie er oog voor heeft.

–

Robert-Henk Zuidinga (1949) studeerde Nederlandse en Engelse Moderne Letterkunde aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Hij schrijft over literatuur, taal- en bij uitzondering – over film.

De drie delen Dit staat er bevatten de, volgens zijn eigen omschrijving, journalistieke nalatenschap van Zuidinga. De boeken zijn in eigen beheer uitgegeven. Belangstelling? Stuur een berichtje naar: info@rozenbergquarterly.com– wij sturen uw bericht door naar de auteur.

Dit staat er 1. Columns over taal en literatuur. Haarlem 2016. ISBN 9789492563040

Dit staat er II, Artikelen en interviews over literatuur. Haarlem 2017. ISBN 9789492563248

Dit staat er III. Bijnamen en Nederlied. Buitenlied en film, Haarlem 2019. ISBN 97894925636637

Koninkrijk op eieren. Reflecties op 10 jaar 10.10.10

Samengesteld door Joop van den Berg & René Zwart

Samengesteld door Joop van den Berg & René Zwart

Uitgave ADCaribbean b.v. 2020. ISBN ontbreekt

Vijftig mensen die beroepsmatig geïnteresseerd zijn in de verhoudingen binnen het Koninkrijk hebben zich op verzoek van de samenstellers van de bundel Koninkrijk op eieren. Reflecties op 10 jaar 10.10.10, Joop van den Berg & René Zwart, gebogen over de vraag hoe we ervoor staan tien jaar na 10.10.10.

Mr. Pieter van Vollenhove, voorzitter van het Comité Koninkrijksrelaties, ziet die deelname als teken dat het Koninkrijk ‘bij velen leeft’. In zijn Voorwoord vertelt hij dat hij ‘van de samenstellers vernam [..] dat vrijwel iedereen die benaderd is onmiddellijk bereid was tot medewerking. En dat hun betrokkenheid bij het Koninkrijk zo groot is dat vrijwel niemand zich heeft gehouden aan de voorgestelde lengte. Ook dat spreekt mij zeer aan, omdat het past bij één van mijn favoriete motto’s: wie schrijft die blijft!’

De conclusie dat het onderwerp bij velen leeft gezien de bereidwilligheid van de auteurs, getuigt van een positieve levenshouding. Want de vijftig auteurs zijn niet willekeurig uit een volgepakt voetbalstadion geplukt.

De inleiding, geschreven door de samenstellers, heeft als titel Een les voor de toekomst.

Daarmee geven de auteurs direct de eindconclusie van de bundel prijs. Na lezing van al die bijdragen kun je nl. niet anders concluderen dan dat het jubileum geen reden voor feestelijkheden is.

Zoals René Zwart in de Proloog de stand van zaken samenvat:

‘Voor velen op de eilanden is het leven er alleen maar slechter op geworden: sinds 10-10-10 heeft de armoede er een vlucht genomen, zelfs in de bijzondere BES-gemeenten die onder de rechtstreekse hoede van Haagse ministeries vallen.’

Mocht de lezer nog hopen op een meevaller, concludeert Zwart een paar regels verderop: ‘Minstens zo treurig is het gesteld met de bestuurlijke verhoudingen. Exemplarisch daarvoor is dat uitgerekend de wens geschillen in de kiem te kunnen smoren een hardnekkige bron van wrevel is.’

Dan moet je nog aan de opstellen beginnen.

De eerste bijdrage is van mevrouw Camelia-Römer. Zij was twee keer minister-president en meerdere keren minister van de Nederlandse Antillen. Van april 2015 tot 24 juli 2020 was zij, met enkele maanden onderbreking, minister in Curaçao. In 2006 werd zij door toenmalig premier De Jongh-Elhage gevraagd zitting te nemen in het adviseursteam dat de onderhandelingen op weg naar 10-10-10 begeleidde.

In vijf bladzijden weet mevrouw Camelia-Römer de lezer de laatste restjes hoop op een blijmoedige bundel te ontnemen.

Één alinea vat het ongenoegen over de onderlinge verhoudingen helder samen, en laat de historische context zien van waaruit gedacht wordt:

‘Het bizarre is dat de regering van Curaçao in 2016 nog publiekelijk complimenten van het College financieel toezicht ontving en nu opeens krijgen we te horen dat er de afgelopen tien jaar niks goed is gegaan.

Dat is niet geloofwaardig. Natuurlijk zijn er zaken die beter kunnen en moeten. Wij zijn mensen in een land in wording, komend uit de pijnlijke geschiedenis van slavernij en het zijn van kolonie, eerst als slaven en daarna als ‘onderdanen’, steeds ondergeschikt gemaakt aan ‘personen’ uit het ‘moederland’, en zijn middenin in een emancipatorisch proces werkend aan de opbouw van onze eigenwaarde, uitgedrukt in een nog verder zelf te schrijven historie van onze Afrikaanse, Europese, Indiaanse en overigens gemengde achtergrond, onze tambu, ons Papiamentu, onze kruiden, onze kunst enzovoorts.’

De tweede bijdrage is van de hand van Alexander Pechtold. De heer Pechtold was van 31 maart 2005 tot 3 juli 2006 minister voor Bestuurlijke Vernieuwing en Koninkrijksrelaties en daarna tot 10 oktober 2019 voorzitter van de Tweede Kamerfractie van D66. Van 2017 tot 2019 was hij tevens voorzitter van de vaste Kamercommissie voor Koninkrijksrelaties.

De heer Pechtold is wat verdrietig als hij terugkijkt op tien jaar 10.10.10: ‘Het begint ermee dat je in Den Haag met een lampje moet zoeken naar de weinigen die echt geïnteresseerd zijn in de eilanden. Het is een dossier waarmee je niet kunt scoren.’

Daar zit je dan.

De bijdrage van de huidige baas van de rijbewijzen eindigt met de vaststelling dat we alles anders zouden doen als we niet die gemeenschappelijke geschiedenis kenden.

In de woorden van Pechtold:

Het is waar: als je nu vanaf nul opnieuw mocht beginnen en op de tekentafel een nieuwe staat maakt, dan zou niemand een koninkrijk als het onze maken. Het zijn de historische toevalligheden die ons bij elkaar brachten. Maar toch, ons gezamenlijk verleden, onze gemeenschappelijke waarden en gedeelde symbolen verbinden ons. En brengen ons samen in een koninkrijk dat meer is dan een staatsvorm. Het gaat om gelijke kansen en gelijke rechten voor alle mensen, bescherming van kwetsbaren, goed onderwijs en goede gezondheidszorg en voldoende banen, dat zijn de beste garanties voor een welvarende toekomst.

Hoe edelmoedig deze slotconclusie ook klinkt, de bewoners van de zes eilanden hebben deze woorden in de afgelopen jaren in allerlei varianten voorbij zien komen. Vermoedelijk zullen ze na lezing niet naar het strand hollen om de horizon af te speuren op zoek naar die onvermijdelijke stip.

Het is verleidelijk om alle bijdragen langs te gaan. Zij verdienen alle aandacht.

Want de bijdragen geven een goed overzicht van de verschillende visies op de geschiedenis en daarmee inzicht in de huidige verhoudingen.

Het is te hopen dat het boek een groot publiek weet te vinden.

De kosten kunnen geen drempel zijn, ‘Koninkrijk op eieren’ is als e-boek gratis te downloaden via: www.koninkrijk.nu.

Dat je bij lezing zo nu en dan struikelt over de cliché’s van de politici, is misschien onaangenaam. Maar als je wilt dat je kippen eieren leggen, moet je het kakelen verdragen.

Noam Chomsky: Trump Is Willing To Dismantle Democracy To Hold On To Power

While it’s still too early to predict the likely outcome of the November 2020 presidential election, Donald Trump continues to fall behind in national polls while pulling dirty electoral tricks in the hope of defeating Democratic challenger Joe Biden. Much of Trump’s hope for victory rests with his “law and order” campaign, which promotes lies about mail-in-voting fraud in order to preemptively discredit the election results if they are in Biden’s favor. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Noam Chomsky discusses the national and international significance of Trump’s refusal to commit to a “peaceful transition to power” and his reliance on conspiracy theories.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, with slightly more than two weeks away from the most important national elections in recent U.S. history, Trump’s campaign continues to harp on the message of “law and order” — a political tactic that authoritarian leaders have always relied on in order to control people and to strengthen their grip on a country — but refuses to accept a “peaceful transition to power” if he loses to Biden. Your thoughts on these matters?

Noam Chomsky: The “law and order” appeal is normal, virtually reflexive. Trump’s threat to refuse to accept the result of the election is not. It is something new in stable parliamentary democracies.

The fact that this contingency is even being discussed reveals how effective the Trump wrecking ball has been in undermining formal democracy. We may recall that Richard Nixon, not exactly revered for his integrity, had some reason to suppose that victory in the 1960 election had been stolen from him by Democratic Party machinations. He did not challenge the results, placing the welfare of the country above personal ambition. Al Gore did the same in 2020. The idea of Trump placing anything above his personal ambition — even caring about the welfare of the country — is too ludicrous to discuss.

James Madison once said that liberty is not protected by “parchment barriers” — words on paper. Rather, constitutional orders presuppose good faith and some commitment, however limited, to the common good. When that is gone, we’ve moved to a different sociopolitical world.

Trump’s threats are taken quite seriously, not only in extensive commentary in mainstream media and journals, but even within the military — which might be compelled to intervene, as in the tinpot dictatorships that are Trump’s model. A striking example is an open letter to the country’s highest ranking military officer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Mark Milley, from two highly regarded retired military commanders, Lt. Colonels John Nagl and Paul Yingling. They warn Milley: “The president of the United States is actively subverting our electoral system, threatening to remain in office in defiance of our Constitution. In a few months’ time, you may have to choose between defying a lawless president or betraying your Constitutional oath” to defend the Constitution against all enemies, “foreign and domestic.”

The enemy today is domestic: a “lawless president,” Nagl and Yingling continue, who “is assembling a private army capable of thwarting not only the will of the electorate but also the capacities of ordinary law enforcement. When these forces collide on January 20, 2021, the U.S. military will be the only institution capable of upholding our Constitutional order.”

With Senate Republicans “reduced to supplicant status,” having abandoned any lingering shreds of integrity, General Milley should be prepared to send a brigade of the 82nd Airborne to disperse Trump’s “little green men,” Nagl and Yingling advise. “Should you remain silent, you will be complicit in a coup d’état.”

Hard to believe, but the very fact that such thoughts are voiced by sober and respected voices, and echoed throughout the mainstream, is reason enough to be deeply concerned about the prospects for U.S. society. I rarely quote New York Times senior correspondent Thomas Friedman, but when he asks whether this might be our last democratic election, he is not joining us “wild men in the wings” — to quote McGeorge Bundy’s term for those who don’t automatically conform to approved doctrine.

Meanwhile, we should not overlook how leading elements of Trump’s “private army” are showing their mettle in their usual terrain of deployment: the cruel Arizona desert to which the U.S., since Clinton, has driven miserable people fleeing from our destruction of their countries so that we may evade our responsibility — both legal and moral — to offer them an opportunity for asylum.

When Trump decided to terrorize Portland, Oregon, he didn’t send the military, probably expecting that it would refuse to follow his orders, as had just happened in Washington, D.C. He sent paramilitaries, the most fierce of them the tactical unit BORTAC of the Border Patrol, which is given virtually free rein with the “damned of the earth” as its targets.

Immediately on returning from carrying out Trump’s orders in Portland, BORTAC returned to its regular pastimes, smashing up a flimsy medical aid center in the desert where volunteers seek to provide some medical aid, even water, to desperate people who managed somehow to survive.

Don Quichot, Reve en Zwagerman: literaire naamwoorden

Heet homerisch lachen naar Homerus? (Ja, in zijn Ilias beschrijft hij hoe de hinkende Hephaestus ‘een onuitblusbaar gelach onder de goden’ deed opstijgen. We hebben trouwens ook een homerische strijd en de homerische vergelijking.)

Is een platonische liefde vernoemd naar Plato? (Ja, in zijn dialoog Symposion bespreekt hij de dialectiek der liefde, d.w.z. hoe het verlangen (eros) het lichamelijke overstijgt en zich uiteindelijk richt op de absolute schoonheid. Onze taal kent ook nog de platonische maaltijd, waarbij meer geredeneerd dan gegeten wordt.)

Danken we het sadisme aan markies de Sade? (Ja, Donatien Alphonse François Marquis de Sade (1740-1814) beschreef in verscheidene van zijn boeken varianten van de liefde die er niet om logen. Het masochisme komt van de Oostenrijkse schrijver en journalist Leopold Ritter von Sacher-Masoch (1836-1895), die, met name in Venis im Pelz (1870), schreef over de tegengestelde aandrang.)

De literatuur heeft de nodige bijvoeglijke en – in mindere mate – zelfstandige naamwoorden gegenereerd. In een paar gevallen zijn die voortgekomen uit de naam van een personage. Zoals datisme, een overbodige opeenstapeling van synoniemen. Het Eponiemenwoordenboek (Amsterdam, 1990) van Ewout Sanders vermeldt: `Datisme dankt zijn bestaan aan de Atheense blijspeldichter Aristophanes. In 421 voor Chr. liet deze in De Vrede een zekere Trygaeus zeggen: Welnu, dit is het! Hier komt het ouwe deuntje van Datis dat hij zong als hij zich aftrok tijdens het middaguur: “Ik ben verrukt, ik ben verheugen, ik ben in de wolken.”’

Een verhaal apart is dat van Pierre Abélard, ook bekend als Petrus Abaelardus, en Héloïse. Abélard (1079-1142) was een monnik en docent, Héloïse (1101-1164) was zijn ruim 20 jaar jongere pupil. Het leeftijdsverschil en de celibataire plicht weerhielden het stel niet van een gepassioneerde relatie, waaruit een zoon voortkwam, Astrolabus. Ze trouwden in het geheim maar moesten gescheiden verder leven. Ze werden beroemd door hun heftige correspondentie en werden pas in 1817 verenigd op de Parijse begraafplaats Père-Lachaise.

Fulbertus, Abélards superieur en Héloïses oom, bleek echter dermate verstoord over hun liefde, dat hij een paar boeven engageerde om de arme Pierre te straffen: zij castreerden hem.

Hij zal niet vermoed hebben, dat dat ooit nog een plaats in een Nederlands woordenboek zou opleveren. In de Woordenschat van Taco de Beer en E. Laurillard uit 1899, wordt het werkwoord abelardiseeren [sic] als volgt gedefinieerd: ‘ontmannen, van Abélard, een beroemd geleerde der 12de eeuw, († 1142) op wien de krankzinnige Fulbert, vader [sic] van Heloise, deze bewerking met geweld deed toepassen’. In de latere drukken van onze belangrijkste woordenboeken komt abelardiseren niet meer voor.

Het verhaal van Abélard en Héloïse werd het onderwerp van talloze kunstwerken, van romans en opera’s tot schilderijen en gedichten. De rebelse Franse dichter François Villon (1431-1463), bijvoorbeeld, verwijst ernaar in een van zijn ballades, de Ballade des dames du temps jadis. Het tweede couplet daarvan begint met

Où est la très sage Helloïs,

Pour qui fut châtré et puis moine

Pierre Esbaillart à Saint-Denis ?

Pour son amour eut cette essoine.

door Ernst van Altena in de Ballade van de dames uit vroeger tijden vertaald als

Heloise, ach waar is zij,

die zo schoon was en veel verstand had?

Abelard trok de monnikspij

voor haar aan, toen men hem ontmand had.

In de Nederlandstalige literatuur wijdden Hendrik Tollens en Jan van Nijlen elk een gedicht aan het ongelukkige paar, de eerste met ‘Heloïze aan Abelard’ in Gedichten, derde deel (1815), de tweede met ‘Héloïse en Abélard’ in de bundel De vogel Phoenix uit 1928, niet te verwarren met de gelijknamige bundel van M. Vasalis.

A Global Green New Deal Project

The position of the Academies of Science from more than 80 countries and scores of scientific organizations is that global warming is human-caused through the release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels (coal, natural gas, oil) to generate power. In fact, scientists have known for decades how carbon dioxide traps heat in the atmosphere and contributes to global warming, with nuclear weapons physicist Edward Teller actually warning the oil industry all the way back in 1959 how its own activities will end up having a catastrophic impact on human civilization.

The position of the Academies of Science from more than 80 countries and scores of scientific organizations is that global warming is human-caused through the release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels (coal, natural gas, oil) to generate power. In fact, scientists have known for decades how carbon dioxide traps heat in the atmosphere and contributes to global warming, with nuclear weapons physicist Edward Teller actually warning the oil industry all the way back in 1959 how its own activities will end up having a catastrophic impact on human civilization.

Naturally, the petroleum industry went on to bury under the rug Teller’s scientific explanation of the impact of carbon dioxide on climate change, along with many other scientific reports on the same topic that came to its attention in the years thereafter. Of course, over the years, there has been an explosion of scientific studies about climate-change impacts on all aspects of civilized life. Most of them are produced by leading university and research centers around the world, but also from NASA, the US Department of Defense, the Federal Reserve, and the Bank of England. The evidence for global warming is indeed compelling.

Nonetheless, we live in an age where the discovery of truth through reason and science has come under attack by far too many in the present-day world, including elected officials, especially in a country like the United States where religiosity is prevalent and only 40% of its citizens place much confidence in the scientific community.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, climate change denialism is still quite prevalent in some parts of the world, especially in the United States among conservatives, which undoubtedly explains why at the Republican National Convention (August 24-27, 2020) the climate change threat was never even mentioned. For Donald Trump (and many of his followers), climate change is a “hoax” and, as the president said during his visit to California in mid-September, “science doesn’t know” what’s causing wildfires. But he does: they are caused by “exploding trees” and poor forest management.

The climate crisis is real, and the only question is how to deal with this truly existential threat. Stopping fossil fuel emissions and moving to clean, renewable sources of energy is the obvious and most widely accepted solution, and the game-changer is the idea of a Green New Deal. “Some form of a Green New Deal is essential to ‘save the planet,’” says Noam Chomsky in the newly published book Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (Verso, 2020). But which form, as there are several different schemes of the Green New Deal?

Robert Pollin, co-author of the aforementioned book, outlines a detailed (Global) Green New Deal project which the world’s most revered public intellectual (Noam Chomsky) endorses wholeheartedly. Pollin’s Global Green New Deal project to tackle the existential threat of climate crisis is all-encompassing as it addresses virtually every question associated with the transition to a “green economy.” Unlike other Green New Deal proposals, it is short on generalizations and extensive on specifics, supported with ample of economic data and cost accounting assessments. In fact, Pollin has designed several state-level Green New Deal proposals, including for Puerto Rico. And his take on the transition to a “green economy” is quite different from some of the other Green New Deals that have been proposed by various other progressives, including Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, Bernie Sanders, and Naomi Klein.

Here, I wish to highlight some very specific items and ideas that are included in Robert Pollin’s detailed Global Green New Deal project, which are rarely covered by the various Green New Deal proposals in circulation.

1. Applying the insurance option to climate change: To skeptics about the complete accuracy of the scientific predictions to climate-change impacts, Pollin suggests that “we should think of a global Green New Deal as exactly the equivalent of an insurance policy to protect ourselves and the planet against the serious prospect – thought not the certainty –that we are facing an ecologic catastrophe.” The only question is how much climate insurance we should purchase. Indeed, most homeowners are willing to buy homeowners insurance even if there is only 1% or less risk of a loss caused by “perils” (fire, lightning strikes, etc.). Isn’t it therefore irrational to suggest that we should not take measures to safeguard the planet from the potential impacts of global warming?

2. Irrational and unrealistic to expect capitalists on their own to get us out of the climate crisis: To those who wish to rely on capitalism and market-oriented solutions to climate change, Pollin argues convincingly that just because capitalism got us into the climate change mess, it is absurdly naïve to believe that capitalist entrepreneurship is the way out of a potential climate change catastrophe. “Forceful forms of government intervention,” as in the case of the Great Depression, where the Roosevelt administration assumed direct role in the management of the economy, such as by embarking on massive public investment projects and ownership of critical industries, are absolutely essential for stopping fossil fuel emissions and making a transition to a clean and renewable sources of energy, argues Pollin. In this context, market-driven plans for combatting global warming, such as the carbon tax plan advocated by many mainstream economists who are still clinging tightly onto the straightjacket of neoliberal discourse, are highly inadequate, if enforced without other provisions and regulations, to make an impact on the containment of the climate crisis.

3. Public ownership of the energy industry is also not the way out. 90 percent of the world’s fossil fuel assets are already publicly owned, thus it’s obvious that public ownership of energy companies is not the solution. While it is true that publicly owned fossil fuel enterprises do not operate under exactly the same profit incentives as capitalist firms, their incentive structures are approximately equivalent – with careers, promotions, salaries, prestige all wrapped up in selling fossil fuels and generating maximum revenues. Also, fossil fuel revenues are the big source of government revenues to fund everything. The more general point on this matter, according to Pollin, is that we need to think about a variety of public and private ownership forms being given the opportunity to flourish—including small-scale cooperative ownership and similar innovations.

- Page 2 of 3

- previous page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- next page