Ella Shohat. Ills.: Joseph Sassoon Semah

Source: jadaliyya.com. Seven decades after their massive exodus, the narrative about the departure of Iraqi Jews is hardly settled, not even within the displaced community itself. A continuous millennial existence in Mesopotamia was rendered impossible in the wake of a historical vortex generated by overpowering political forces and conflicting ideologies. The fall of the Ottoman Empire, the subsequent rule of British colonialism, and the emergence of Jewish and Arab nationalist movements generated internal and external political pressures on the Jewish-Iraqi community. The Zionist redefinition of Jewishness as an ethno-nationality, which was in discord with its traditional status as a religion, brought about new dilemmas and tensions, irrespective of how the Arab Jews may have viewed their Jewish affiliation. The clashing political camps of colonialism, monarchism, and communism, as well as of Zionism and Iraqi/Arab nationalism, underline the story of a community pulled in opposite directions. Consequently, Arab Jews ended up becoming the collateral damage of warring ideological zones, a diasporization born out of historically new colliding movements.

The majority of Iraqi Jews were dislocated in the wake of the U.N. partition of Palestine, the establishment of the State of Israel, and the nakba. Between 1950—1951, about 120,000 Iraqi Jews ended up departing, largely for Israel, in a process referred to as tasqit al-jinsiyya— the precondition of relinquishing Iraqi citizenship required for exiting without the possibility of return. This exodus, recalled among Iraqi Jews as “sant al-tasqit” (the year of the tasqit), is conventionally narrated as the end of the Babylonian Exile and the fulfillment of the promised messianic return to Zion. Within Jewish tradition, Babylon is a site of the Diaspora, the ultimate exilic condition epitomized in the Biblical phrase “By the waters of Babylon we laid down and wept, when we remembered Zion.” Converting religious concepts into an ethno-nationalist discourse, the Zionist notion of ‘Aliya (literally “ascendency”) has had the effect of mystifying the epic-scale cross-border movement between enemy zones. What was lived as a wrenchingly chaotic experience was emplotted as having a liturgically-sanctioned purpose culminating in a kind of happy end. Indeed, the very official term deployed for the airlifting of Iraqi Jews to Israel, “Operation Ezra and Nehemia” invoked the prophets associated with the Biblical return to Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the Temple. In a more modern and secular parlance, the nomenclature celebrated the return to the legitimate “Land of origins.” Yet, such discourses downplayed the multilayered social, material, and emotional toll of the dislocation—for instance, the fact that many Iraqi Jews in Israel continued to pine for a place that had been seen simply as home. What is often recounted as the “ingathering of the exiles” and the restoration of “the Diaspora” to Jerusalem, was in fact a painfully complicated experience, an ongoing intergenerational trauma which engendered an ambivalent sense of belonging for dislocated Middle Eastern Jews. This return, within a longer historical perspective, could also be viewed as a new modality of exile, hence my inversion (in “Reflections of an Arab-Jew,” 1992): “By the waters of Zion we laid down and wept, when we remembered Babylon.”

Departing and its Discontents

In many ways, the departure is a consequence of a shifting set of geopolitical circumstances in the post-World War I era, but mostly of the facts-on-the-ground Yishuv settlements, the 1917 Balfour Declaration and the 1947 U.N. resolution to partition Palestine. The 1948 foundation of the State of Israel and the consequent massive dislocation of Palestinians to neighboring Arab countries placed indigenous Middle Eastern Jews in an acutely vulnerable position. Within the landscape of crossed-affinities, Arab Jews had to pledge allegiance to one identity articulated by two clashing movements— either “Jewish” or “Arab” —both newly defined under a novel historical banner of ethno-national affiliation. In dissonance with the traditional view of Judaism as a religion, the Zionist ethno-nationalist redefinition generated new predicaments for the community itself. Some of the Iraqi-Jewish youth came to view Israel as a promising option, especially since Arab nationalism also generated new predicaments for Arab Jews. Ironically, the Zionist view of Arabness and Jewishness as mutually exclusive gradually came to be shared by Arab nationalist discourse, placing Arab Jews on the horns of a terrible dilemma. The rigidity of both paradigms has produced the particular Jewish-Arab crisis, since neither paradigm can easily contain porous identities and multiple belongings.

The Zionist pressure to dislodge Jewish communities and end “the gola” (Diaspora) on the one hand, and the Arab nationalist gradual equation of Judaism with Zionism, on the other, brought about the eventual parting of Arab Jews from their homes. Within the rapidly shifting environment, Jews in Iraq, Egypt, Syria and so forth had to defend a Jewishness that was associated for the first time in their history not with religious culture but with colonial nationalism. These momentous events resulted in general expressions of hostility and various discriminatory measures toward indigenous Jews throughout the region. In the post-1948 era, with the deteriorating conflict in Palestine, the push-and-pull pincer movement became increasingly more intense. While the Palestinians were experiencing the nakba, Arab Jews woke up to a new world order that could not accommodate their simultaneous Jewishness and Arabness. The Orientalist split between “the Jew” and “the Arab” as two separate entities, already in embryo within colonized Middle East/North Africa, was to fully materialize with the 1947 partition. It resulted in the corollary dispossession and dispersal of Palestinians largely to Arab zones, as well as in the concomitant dislocation of Arab Jews largely to Israel. Thus, the dislocation is embedded in a new ethno-nationalist lexicon of Jews and Arabs. The historical question is whether Arab regimes bear the full weight of the responsibility for the dislocation of Arab Jews, who consequently had to be rescued by Israel; or whether, the emergence of the Zionist movement could itself be seen as igniting turmoil for Middle Eastern Jews who until the escalation of the Jewish/ Arab conflict were not in need of saving? Or, perhaps both?

Since post-’48 Palestinian refugees were arriving en masse to the Arab world, Arab Jews were placed in an impossible position. A product both of colonialism and nationalism, the overpowering regional conflict situated Arab Jews between crushing opposing forces, while the community as a whole had little control over circumstances that had colossal bearing on their very existence. The departure from the Arab world, in this sense, was not simply the result of a decision made solely by the community and its individual members themselves. It took place, for the most part, without the Arab Jews’ comprehensive awareness of what was the role played by each party in their alarming push-and-pull situation; and thus, what was really at stake in their departure and what was yet to come. Terrified by the indiscriminate animosity propagated against “al-yahud” in Iraq, the Jewish Iraqis were simultaneously buffeted by manipulated confusion, misunderstandings, and projections provoked by a Zionism that blended messianic religiosity with secular nationalist purposes. While on one level, their departure was marked by an anticipation for a land imbricated with liturgical sentiment, on another, it was driven by fear and hope for refuge—key emotional elements compelling the final lock on the doors to their millennial home.

Nationalist paradigms hardly capture the complexity of this historical moment of rupture for Arab Jews. The idiosyncrasies of the situation of a community trapped between two nationalisms—Arab and Jewish—have generated a proliferation of terms to designate the dislocation. In fact, each term used to designate the displacement seems problematic precisely due to the ambiguity of its circumstances. None of the terms—“‘aliya” (ascendancy), “yetzi’a” (exit), “exodus,” “expulsion,” “immigration,” “emigration,” “exile,” “refugees,” “ex-patriots,” and “population-exchange—” are adequate. In the case of the Palestinians, the forced mass exodus corresponds to the conventional understanding of the notion “refugees,” since they never wanted to leave Palestine and have maintained the desire to return. In the case of Arab Jews, the question of will, desire, and agency remain much more ambivalent and ambiguous.

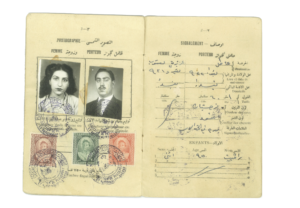

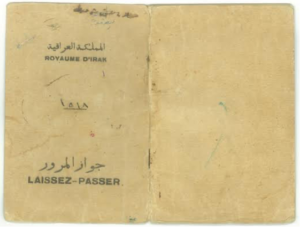

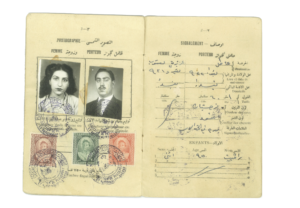

The very proliferation of terms suggests that it is not only a matter of legal definition of citizenship that is at stake, but also the issue of mental maps of belonging. The post-’48 circumstances generated a rather anomalous situation that to my mind was neither the paradigmatic refugee nor the archetypal immigrant story. Could the departure of the Iraqi Jews be seriously regarded as an exercise of free will and a matter of straightforward agency? And once out of Iraq and unable to go back, even for a visit, did they regret the impossibility of their return? In the post-’48 climate of uncharted anxiety about their Iraqi future, the various push-and-pull forces steered many into the tasqit. The Meir Tweig synagogue inaugurated in 1942 and located in the affluent district of al-Bataween, was one of the sites for the registration of the departing Jews. As a tasqit point, the synagogue was no longer merely a gathering place for worship and socializing, but a site of rupture—of giving up Iraqi citizenship in exchange for a laissez-passer stipulating that the document holder is definitively not permitted to return. (Stamped in the Arabic as “la yasmahu li–hamilihi bi–l–‘awda illa al-‘Iraq batatan.”) The virtually over-night cross-border movement was thus not only a physical dislocation but also a cultural and emotional displacement, a defining traumatizing event in the recent history of Iraqi Jews.

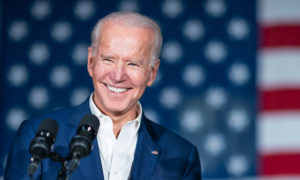

Registration point for departure from Iraq at the Meir Tweig Synagogue[1]

These traumatic displacements have shaped new national and ethnic identities where officially stamped classifications did not necessarily correspond to cultural affiliation and political identification. Emotional belonging has existed in tension with identity cards and travel documents such as passports and laissez-passers, or in the absence of such papers altogether. Some have been shorn of citizenship for decades (such as post-1948 Palestinians who repeatedly moved from camp to camp); while others have partaken in forms of citizenship that have not been hospitable to the complexities of their cultural identity (like the Arab Jews). Against this backdrop, “Arab” and “Jew,” as I suggested in my earlier work, came to form mutually exclusive categories, with “the Arab-Jew” becoming an ontological oxymoron and an epistemological subversion. The notions of “Palestine” and “the Arab-Jew,” in this sense, stand not simply for historical facts, and for their contestations, but rather for a critical prism. Just as all communities, traditions, and identities may be said to be “invented,” the idea of “the Arab-Jew,” I have argued, provides a post-partition figure through which to critique segregationist narratives while also opening up imaginative potentialities.

One could provide an analysis, as some historians have indeed done, of a multidimensional political context that engendered the vulnerable position of Arab Jews within Arab spaces. Critical forms of discourse and scholarship have delineated the intricate positioning of ethnic and religious minority-communities throughout the region, taking on board such issues as: the colonial divide-and-conquer tactics and strategies that actively endangered various “minorities” including Arab Jews; the implementation of Zionism as an exclusivist project toward the Arabs of/in Palestine; the hostile rhetoric of some forms of Arab nationalism that deemed all Jews Zionists; the massive arrival of desperate Palestinian refugees in Arab countries; and the various “on the ground” activities, some violently provocative, to dislodge Iraqi, Egyptian, or Moroccan Jews from their homelands.

Image source: https://jewishrefugees.blogspot.com/2017/11/an-israeli-stamp-on-cereal-packet-could.html?m=1

Even if a growing number of Jews in countries such as Iraq were expressing a desire to go to Israel (or to the Eretz Israelin liturgical parlance), the question is why, suddenly, after millennia of not doing so, would they leave overnight? The displacement, for most Arab Jews, was the product of entangled circumstances in which panic and disorientation, rather than a simple desire for ‘aliya, in the nationalist sense of the word, played a key role. In Iraq, even subsequent to the establishment of the State of Israel, the Jewish community was founding new enterprises, a fact that hardly indicates an institutionalized or organized plan to evacuate. The ‘‘ingathering’’ then seems less natural and inevitable when one takes into account the intricate political environment that engendered the departure from Iraq, to wit: 1) the efforts of the Zionist underground in Iraq to denigrate the authority of the traditional Jewish community leaders, especially Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, who did not subscribe to this new version of Jewishness;[2] 2) its attempts to place a ‘‘wedge’’ between the Jewish and Muslim communities;[3] 3) the Iraqi institutionalization of discriminatory practices toward Jews; 4) the vehement anti-Jewish propaganda visibly circulating in the public sphere, especially as channeled through the Istiqlal (Independence) Party; 5) the reticence on the part of many non-Jewish Arab intellectuals to spell out the distinction between “Jews” and “Zionists”; 6) the failure of the Iraqi political leadership to actively secure the place of Jews in the country; 7) the persecution of communists, among them Jews, who opposed the Zionist idea; 8) the secretive agreements between some Iraqi and Israeli leaders concerning the departure of Jews to Israel; and 9) the misconceptions, on the part of many Arab Jews, about the differences between their own religious identity, affiliation, or sentiments and the modern nation-state project, premised on a Eurocentric secular vision even while invoking a quasi-religious messianic rhetoric.

To this day, discussion of the circumstances that led to the departure of Iraqi Jews provokes a heated political quarrel especially vis-à-vis the 1948 Palestinian refugee question. The dominant Arab nationalist discourse has represented the mass departure of Jews as a sign of the Jewish betrayal of the Arab nation. The dominant Israeli discourse, meanwhile, has narrated the same departure as a story of expulsion of Jews. More recently, the issue of “Jewish refugees from Arab and Muslim countries” has been linked to the 1948 Palestinian exodus as part of an effort to dispute Palestinian claims of expulsion and dispossession. As a new version of the older rhetoric of “population exchange” between Arab and Jewish refugees, the nakba and the tasqit have been lately circulating as equivalent historical events. When discussed together in the international public sphere, the discourse on the mass departure from Iraq is paralleled to the 1948 Palestinian refugees in a kind of contestation of the nakba (the catastrophe), performing a combat over the monopoly on historical suffering. The pairing of the nakba exodus with the presumably equivalent case of the tasqit exodus has attempted to assuage Israeli responsibility for the Palestinian dislocation. In its updated version, in a kind of “narrative envy” usually projected onto Palestinian intellectuals, each argument used to reject the nakba expulsion is echoed with a similar argument and phrasing with regards to Arab Jews. The tragedy of “the Palestinian refugees” is answered with the tragedy of “the forgotten refugees from Arab countries;” “the expulsion of Palestinians” is cancelled out by “the expulsion of Jews from Arab countries;” “the transfer” and “ethnic cleansing” of Palestinians is correlated with “the transfer” and “ethnic cleansing” of Jews from Arab countries; and even “the Palestinian nakba” is retroactively matched with a “nakba of Jews from Arab countries.” Yet, without engaging the consequences of nationalism, the recent campaign for “justice for the forgotten Jewish refugees from Arab countries” silences the violent dispossession of Palestinians summed up in the word nakba, as if one event annulled the ethical-political implications of the other.

Some versions of the “Jewish refugees from Arab countries” discourse, moreover, embeds the assumption of Muslims as perennial persecutors of Jews, absorbing the history of Jews in Arab/Muslim countries into what could be called a “pogromized” version of “Jewish History.” In its most tendentious forms, this rhetoric incorporates the Arab Jewish experience into the Shoah, evident for example in the campaign to include the 1941 farhud attacks on Jews in Iraq in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. One can denounce the violence of the farhud, and even connect it to Nazi propaganda in Iraq coming out of Berlin, without instrumentalizing it to equate Arabs with Nazis, or forge a discourse of eternal Muslim anti-Semitism. Apart from the fact that during the farhud some Muslims also protected their Jewish neighbors, the designation of the violent event as a pogrom has shaped a Eurocentric historical narrative for Iraqi Jews. This millennial persecution discourse connects the dots from pogrom to pogrom, projecting the historical experience of Jews in Christian-Europe onto the experience of Jews in Muslim spaces. Such discourse farhudizes, as it were, Iraqi-Jewish history, as though the 1941 moment is emblematic of the story of “Jews under Islam.” The present-day discussion of the tasqit al-jinsiyya has, in sum, been subjected to contradictory interpretations and marshalled for radically divergent purposes, with each historical reading having serious legal, political, and cultural implications.

Remaining and Its Discontent

The community’s displacement evokes two contradictory exilic/homecoming narratives: on the one hand, the Zionist translation of the Biblical redemptive restoration—“kibbutz galuiot”—into a modern nation-state formation; and, on the other, the uprooting of a community from its indigenous geography in Mesopotamia/Iraq. Bavel, traditionally the Biblical locus of Babylonian Exile was after all also the millennial home for Jews whose notion of “Return to the Promised Land” was premised on a set of messianic beliefs. Hence, the historical opposition to the Zionist idea among traditionally observing Jews, for whom the formation of Jewish nationalism signified a rupture with Judaism, advancing a blasphemous idea, a kind of false messiah. The figure of Hakham Bashi (the Chief Rabbi and also the President of the Jewish community) Sasson Khdhuri epitomizes, in a way, the story of a well-established community that came under horrendous pressures leading to its fragmentation and ultimate collapse. With the partition of Palestine and the establishment of the State of Israel, the tasqit resulted in the departure of the majority of Iraqi Jews. However, some did remain in Iraq, enduring family separation. They lived through wars, revolutions, and a dictatorial regime that rendered hellish the situation of all Iraqis, but took on a specifically-compounded reality for Jews, existing as they did under the unrelenting suspicion of disloyalty. Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, along with a few members of his family, was among those who stayed in Iraq,although some of his children left for Israel. The enormous task of representing the community fell largely on the shoulders of the Hakham.[4] Separated until the end of his life from most members of his family, the Hakham continued his role in working to safeguard the Jewish community in Iraq. Throughout five turbulent decades, until his death in Baghdad in 1971, Hakham Sasson Khdhuri navigated the powerful political shifts in the region that had momentous consequences for the Jewish Iraqi community and for Middle Eastern Jews more broadly.

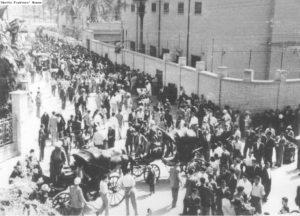

The visit of King Faisal I to the Jewish community in 1924. Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, front row, fourth from right.[5]

Although the majority of Iraqi Jews were not involved in political activity—whether Arab nationalist, Zionist, or communist—they were involuntarily and dangerously implicated in these clashing ideologies. As Iraq’s

Hakham Bashi—the Chief Rabbi and also the President of the Jewish community—Sasson Khdhuri was vocal in publicly distancing the Jewish community from the unfolding events in Palestine. Already, for example in 1936 with the escalation of the conflict between the Jewish Yishuv and Palestinians in Mandatory Palestine, the

Hakham, in his capacity as the president of the Jewish community in Iraq, published a statement on behalf of Iraq’s

al- ta’ifa al-Isra’iliyya (the Israelite community). Its purpose was to clear the Jews of Iraq of any doubt that may be cast on them concerning their possible association with the Zionist movement. “None of the members of the Israelite community of Iraq,” wrote the

Hakham, “have any relation, contact, or joint activities with the Zionist movement, in any respect.” The

Hakham’s declaration insisted that the members of the community never “supported or adopted this movement neither inside nor outside of Palestine,” since the “Jews of Iraq are Iraqis, and they are part of the Iraqi people” who are their “Iraqi brothers” and with whom they share “everything through thick and thin.” The declaration also emphasized that the community’s members “share the same feelings as all Iraqis, whether in joyful or troubled times.”[6] The various pronouncements against the Zionist movement made by religious leaders, including by

Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, have been the subject of much political debate and historiographical interpretation. Was the antagonistic stance toward Zionism a result of deep religious beliefs as indicated by the traditional leaders themselves, or of the leaders’ effort to maintain their grip on power as Zionist activists claimed? Were the petitions signed by the

Hakham across several decades, before and after the

tasqit, a result of coercion by the various Iraqi regimes; or of a desire to shield and protect the vulnerable community; or of a sincere theological rejection of a sacrilegious nationalist idea?

In the post-1948 era, the circumstances of Iraqi Jews were to be transformed dramatically, engendering a general state of insecurity. The ideological tension concerning the future of Iraqi Jews, and the concomitant tensions between the traditional leadership of the community and the Zionist underground movement, reached an unprecedented paroxysm. Mediating between the Iraqi regime and the Jewish community, the Hakham pursued an approach of reconciliation which was regarded by some Jews as, at best, inadequate and which was denounced especially by the Zionists as appeasement of a persecutory regime.[7] With the increasing number of arrests of youths accused of Zionist activity, outraged community members expressed their frustration and an unusual demonstration was organized against the Hakham, leading to his resignation as the head of the Baghdad Jewish community in December 1949.[8]

With the implementation of the tasqit al-jinsiyya law, the anxiety around staying or leaving was palpable. Some of the Hakham’s children, like the oldest and the family’s matriarchal figure, Victoria, were hardcore Zionists. His daughter, Marcelle, for her part, moved to Israel following her communist husband, Edward Semah, who believed that Israel would be a safer place than Iraq, where communism was outlawed. (This former lawyer for the Iraqi military became a lawyer for the Israeli Histadrut, the General Organization of Workers. In Iraq, Edward, according to his son Joseph Sassoon Semah, had naively believed in “the kibbutz’s propaganda” about equality but after arrival to Israel he became deeply disillusioned, “feeling badly mistreated.” On his deathbed, Edward confessed to his son Joseph that if he had had the chance, he would have done it all differently and not moved to Israel.[9]) Although the majority of Iraqi Jews were dislocated in the wake of the partition of Palestine and the establishment of Israel, a minority of the community’s members did not register for the tasqit. The reasons for staying were various, including because they saw themselves first and foremost as Iraqis, and/or they believed the storm would pass, and/or they simply did not want to abandon their lives. After the tasqit and the exodus of the majority of Iraqi Jews, however, the Hakham resumed his leadership position. He continued to practice a flexible approach to Jewishness that accommodated shifting social mores. Deeply involved in the remaining community’s life, in celebration and in mourning, the Hakham was a vital symbolic figure for its Jewish identity.

Hakham Sasson Khdhuri attending a graduation ceremony in the Jewish School, Frank Einy, Baghdad, early 1960s[10]

In the period following the

tasqit, the cataclysmic atmosphere subsided. Although the anxiety linked to the Israel/Arab conflict persisted, this period is nonetheless characterized by relative stability in comparison with the following decade of the post-1963 coup d’état and especially with the violence of the post-1967 War era. With the 1968 coup d’état, the dictatorial Ba

‘athist control of Iraq had a devastating impact on Iraqis of all denominations. The terrorizing measures taken to crush the regime’s real or imagined adversaries led, as we know, to the imprisonment, torture, kidnapping, and killing of many innocent Iraqi citizens generally, but the repression became exacerbated in the case of the Jewish community, now under a blanket suspicion of treason. The surveillance of all Iraqis became for Iraqi Jews a ready-made accusation of collaboration with “

al-‘adu al-Sahyuni” (“the Zionist enemy”), which resulted in violent acts and carried dangerous implications for the very existence of a Jewish community in Iraq. As a result of the Ba

‘ath-sponsored repression between 1969 and 1971, the numbers of the already dwindling community continued to shrink. Faced with a terrifying reality, those who did remain in post-

tasqit Iraq were now compelled into fleeing, leaving behind a virtual eclipse of the once-thriving Jewish-Iraqi communal life. A dispersal from a millennial existence in Mesopotamia that has taken Iraqi Jews to such countries as the U.K., Israel, Canada, and the U.S. By the time of the 2003 invasion, Iraqi Jews in an estimate numbering only in the tens remained during the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime.[11] Despite its indigenous history in the land, the Jewish-Iraqi community came under fateful pressures, which ultimately fractured its intricate social structure and led to its utter fragmentation.

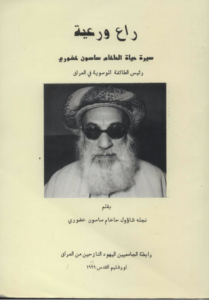

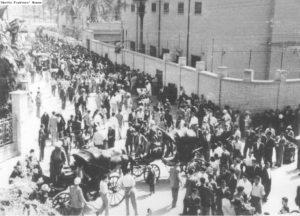

In the 1999 biography of the Hakham written by his son, Sha’ul Hakham Sasson, the author who stayed with his father in Iraq, vehemently attempts to contest the negative image of the Hakham, whose reputation tended to be rather maligned within the Zionist narrative.[12] Entitled in Arabic Ra‘in wa-ra‘eeyya (A Leader and his Community), the book is a testimony of the son who passionately argues that the

Book Cover of Sha’ul Hakham Sasson’s Ra‘ wa-ra‘eeyya (A Leader and his Community)[13]

was without a shadow of a doubt a generously dedicated leader. For the author, the

Hakham acted responsibly and did not abandon his community, staying in Baghdad to shepherd the Jewish life of those who remained. Fearing for the welfare of the remaining community, and indeed for its very existence, the

Hakham defended its members in highly dangerous situations, when Jews were disappearing, detained, tortured, or publicly hanged.

Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, as the president of Iraq’s Jewish community, in other words, acted under extraordinary pressures and at high personal cost.

Indeed, in the tumultuous period of the post-1967 era, the Hakham’s son Sha’ul was himself detained, apparently in an attempt to extort the Hakham to make pro-regime declarations in the face of growing international protestations. Sha’ul, as the Hakham’s son, had symbolic value for the Ba‘ath regime in its effort to counter the vocal diplomatic pressure. In 1969, Sha’ul was included on the regime’s list of Jews to be hung but he was released the following morning while the others accused of spying for Israel were condemned to death. This exception that saved Sha’ul life was commonly attributed to his father’s position, and prompted anger among some Iraqi Jews who cursed and threw stones at the house of the Hakham’s daughter, Marcelle, in Ramat Gan, Israel, for months.[14] In defense against these accusations that charged the Hakham with only intervening on his son’s behalf, Sha’ul suggests in his book that decisions about his release from prison were all the doing of the regime, since his father was ultimately powerless to influence Saddam Hussein’s maneuvers.

In his 1999 prison memoir, Sha’ul Hakham Sasson vividly captures the tormenting experience, recollected while in his nineties in London. Entitled in Arabic Fi jaheem Saddam Hussein: Thalathmi’a wa-khamsa wa-sittun yawman fi “qasr al-nihayya” (In the Hell of Saddam Hussein: 365 Days in the “Palace of the End”), the quotation marks in the subtitle invoke the acerbic epithet describing the prison from which many did not come out alive.[15] After his release, Sha’ul made a decision to leave Iraq, which he calls “my homeland, my birthplace.”[16] But he stayed by his ailing father’s side and only left following the death of the Hakham on 24 March 1971. “I could not imagine,” writes Sha’ul, “leaving my father alone at his age and with all the pains and illnesses he was going through.”[17] Only after the Hakham’s passing, Sha’ul testifies: “I uprooted myself and moved to England where my son Samir lived.”[18] He continues: “I still live in this country…with sad memories, wishing for God to liberate Iraq from its oppressors the Ba‘athists.” Sha’ul expresses his hope for Iraq “to live in peace and prosperity” and for Iraqis to take advantage of “the tremendous resources of the country.” He concludes by wishing that all those “obliged to leave would be able to return to a free and democratic Iraq where all communities and citizens of different religions could coexist in tolerance and equality.”[19]

Both Sha’ul Hakham Sasson’s biography of his father, the Hakham, A Leader and his Community, along with his prison memoir, In the Hell of Saddam Hussein, were published in Arabic by the Jerusalem-based Association of Jewish Academics from Iraq. At the time of the publication in the late nineties, the Association had already printed a number of books written by Jews who stayed in Iraq in the post-tasqit era. In addition to Sha’ul Hakham Sasson’s two books, the list included publications by such figures as Anwar Sha’ul and Meer Basri, who, like the Hakham’s son, ended up leaving Iraq only during the reign of Saddam Hussein. (Basri, after the death of the Hakham, served as the head of the Jewish community, but left in 1974 and lived in London, whereas Sha’ul ended up in Israel.) Such publications by the Iraqi-Israeli editorial team, Shmuel Moreh and Nissim Kazzaz, would seem surprising given the criticism expressed toward these proponents of “the Iraqi orientation,” i.e., of those who believed in staying in Iraq and did not exit to Israel during the tasqit.[20] However, their post-’67 departure is marshalled as evidence of the failure of the Iraqi option carried out by the Jewish leadership. Similarly, the story of the Hakham and his son’s departure resonate with the view that the place of Jews was outside of Iraq, in Israel. The publication of Sha’ul Hakham Sasson’s biography of his father nonetheless signifies a certain shift in the attitude toward the Hakham, even a kind of a Zionist recuperation of the image of the once vehemently denounced head of the community. The Hakham, in this sense, can now be presented positively, but only as part of the metanarrative of the failure of “the Iraqi orientation.” Eli Amir’s 1992 Hebrew novel Mafriah ha-Yonim—The Dove Flyer—depicts a character based on the Hakham within a typically overall critical stance, but which nonetheless endows him with some sympathy vis-à-vis the anti-Jewish Iraqi regime. Within such recuperative gestures, the Hakham’s declarations against the Zionist movement are arguably not being read as signifying a theological perspective or a political reading of the regional map, but rather as a result of a no-choice situation of a Diasporic (galuti) traditional leader appeasing various brutal, even anti-Semitic Iraqi regimes.

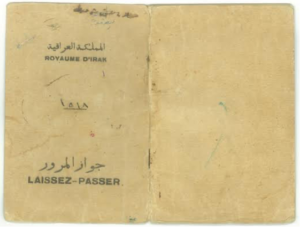

The Iraqi-issued laissez-passer during the tasqit (of Aziza and Sasson, the author’s parents)

The Hakham and his family, in many ways, embody the story of Jewish Iraqis now dispersed in multiple geographies—a Mesopotamian community fragmented and diasporized. In the wake of their exodus from Iraq and the shock of arrival in Israel, Iraqi Jews along with Arab/Sephardi/Middle-Eastern Jews more generally, experienced exclusion, rejection, and otherization as Arabs/Orientals, in a place that had been viewed, at the least, as a refuge. The realization of unbelonging could be glimpsed in the frequent lament: “In Iraq we were Jews, in Israel we are Arabs.”[21] The same year of the Hakham’s death in Baghdad coincided with the founding of the Black Panther movement which protested the discrimination of the Mizrahim in Israel. Indeed, for decades after the tasqit, Iraqi Jews often gave expression to their frustrated sense of betrayal by both Iraq and Israel. They invoked the rumors about the (still disputed) placing of bombs in synagogues and the secretive deal between the Iraqi and Israeli governments under the auspices of the British. They also spoke of both countries as benefitting materially from their departure—Iraq, from their property left behind, and Israel, from turning them into cheap labor. The phrase “ba‘ona”—“they sold us out”[22]—gave expression to an embittered sense of a no-exit situation, from a pre-departure fear of persecution if they were to remain in Iraq to a post-arrival encounter with Euro-Israeli Orientalist attitudes and discourses. Such a post-tasqit sentiment of being doubly out-of-place was hardly in tune with the official narrative of rescuing Jews from their perennial Muslim oppressors, but it did turn the Jewish-Iraqi exodus into a calamitous tale of a scapegoat sacrificed on the altar of the Arab/Israeli conflict.

Notes

[A shorter version of this essay was published in Orient XXI, October 22, 2020. Some of the material on the Hakham is based on my chapter “Remainders Revisited: An Exilic Journey from Hakham Sasson Khdhuri to Joseph Sassoon Semah” in Joseph Sassoon Semah’s On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) III -The third GaLUT: Baghdad, Jerusalem, Amsterdam, Joseph Sassoon Semah & Linda Bouws, eds., Amsterdam: Stichting Metropool Internationale Kunstprojecten, 2020, pp. 26-55.]

[1]Photo sourced from Youth Movements Photos, “Jews of Baghdad gathered beside the Meir Tweig Synagogue, that served as the registration point for legal immigration to the Land of Israel.” Ghetto Fighters House Archive, Catalog No. 10766, https://www.infocenters.co.il/gfh/notebook_ext.asp?item=69546&site=gfh&lang=ENG&menu=1

[2] This effort is clearly expressed in texts written by Iraqi Zionists. See, for example, Shlomo Hillel, Ruah Kadim(Operation Babylon) (Jerusalem: Edanim, 1985), 259–63 (Hebrew).

[3] One of the most debated cases concerns the Zionists’ placing of bombs in synagogues. See Abbas Shiblak, The Lure of Zion (London: Al Saqi, 1986); G. N. Giladi, Discord in Zion (London: Scorpion, 1990).

[4] The spelling of the Hakham’s name here corresponds to its pronunciation in the Jewish-Baghdadi dialect rather than the various transliterations, including in the Hakham’s official seal of the “President of the Jewish Community” (or “Israeli Community,” as defined in Arabic—“Isra’iliyya”—and in Hebrew—“Yisra’elit”—at a time when the word did not yet connote the State of Israel.)

[5] The photo which was taken on the occasion of the visit of King Faisal I to the Jewish community in 1924 is included in Sha’ul Hakham Sasson’s Ra‘ wa-ra‘eeyya (A Leader and his Community) with the following identifications: Front row from right to left: Ruben Zluf, Salim Ishaq, Yehuda Zluf, Hakham Sasson Khdhuri (the president of the court), Hakham Bashi Ezra Dangoor, Mahmud Nadim al-Tabaqcheli, King Faisal I, Safwat Pasha al-‘Awa, Senator Menahem Daniel, Abraham Nahom, Sion Gurji, Tahsin Qadri. Second row from right to left: Dr. Gurji Rabi‘, Eliyahu al-‘Ani, Sasson Mrad, Saleh Shlomo, Yussuf Mrad, Gurji Bahar, Karek Menashi Gurji. p. 263.

[6] The declaration was published in Iraq’s Al-Istiqlal newspaper on October 8, 1936. (The Arabic and Hebrew declaration is located in the Archive of “Va‘ad ha-‘Eda ha-Sefaradit” in Jerusalem.) See Sha’ul Hakham Sasson, “Son of the Former Head of the Jewish Community of Iraq,” Ra‘in wa-ra‘eeyya: Sirat hayat al-Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, ra’is al-ta’ifa al-Musawiyya fi al-‘Iraq (A Leader and his Community: A Biography of the Late Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, Head of the Mosaic Community in Iraq) with an Introduction by Shmuel Moreh, Association of Jewish Academics from Iraq, Jerusalem, 1999, p. 398.

[7] On the Zionist views of Hakham Sasson’s leadership see for example Moshe Gat, Khila Yehudit be-Mashber: Yetz’iat ‘Iraq, 1948-1951 (A Jewish Community in Crisis: The Exodus from Iraq, 1948-1951), The Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History, Jerusalem, 1989; Esther Meir, Ha-Tnu‘a ha-Tziyonit ve-Yehudei ‘Iraq, 1941-1950 (Zionism and the Jews Iraq, 1941-1950), Am Oved Publishers, Tel Aviv, 1993.

[8] Emile Marmorstein, “Baghdad Jewry’s Leader Resigns,” The Jewish Chronicle, December 30, 1949. Republished in Middle Eastern Studies with an introduction by the editor, Elie Kedourie, Vol. 24, No. 3 (July 1988), pp. 364-368. Kedourie suggests that the opposition to the Hakham’s views by “a small, secret group of Zionist activists may have led to his downfall,” p. 364.

[9] Based on a conversation between the grandson of the Hakham, artist Joseph Sassoon Semah, and the author, Ella Shohat, Amsterdam, December 1, 2019.

[10] Photo courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semah

[11] Guy Raz, “The Last Jews of Baghdad in Post-Saddam Iraq, a Disappearing Cultural Legacy,” NPR News, May 22, 2003. https://www.npr.org/news/specials/iraq2003/raz_030522.html

[12] See Sha’ul Hakham Sasson, Ra‘in wa-ra‘eeyya: Sirat hayat al-Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, ra’is al-ta’ifa al-Musawiyya fi al-‘Iraq (A Leader and his Community: A Biography of the Late Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, Head of the Mosaic Community in Iraq) with an Introduction by Shmuel Moreh, Association of Jewish Academics from Iraq, Jerusalem, 1999.

[13] Book Cover of Sha’ul Hakham Sasson’s book Ra‘ wa-ra‘eeyya: Sirat hayat al-Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, ra’is al-ta’ifa al-Musawiyya fi al-‘Iraq (A Leader and his Community: A Biography of the Late Hakham Sasson Khdhuri, Head of the Mosaic Community in Iraq), Published by the Association of Jewish Academics from Iraq, Jerusalem, 1999.

[14] Based on a conversation between the grandson of the Hakham, artist Joseph Sassoon Semah, and the author, Ella Shohat, Amsterdam, December 1, 2019.

[15] Sha’ul Hakham Sasson, “Son of the Former Head of the Jewish Community of Iraq,” Fi jaheem Saddam Hussein: Thalathmi’a wa-khamsa wa-sittun yawman fi “qasr al-nihayya” (In the Hell of Saddam Hussein: 365 Days in the “Palace of the End”), edited by Shmuel Moreh and Nissim Kazzaz. Association for Jewish Academics from Iraq, Jerusalem, 1999.

[16] Fi jaheem Saddam Hussein, p. 59.

[17] ibid

[18] ibid

[19] ibid

[20] Nissim Kazzaz, Ha-Yehudim be-Iraq ba-Me’a há-‘Esrim. Jerusalem, Machon Ben-Zvi, 1991.

[21] I am citing here a sentence that my mother used to repeatedly express.

[22] The phrase formed part of conversations in my family’s circle.

Originally published at jadaliyya.com Jan.14.2021: https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/42239