Amsterdammertje

Mijn zoon is geboren in Amsterdam. Ikzelf ben aan komen waaien, toen ik eenmaal uit het nest vloog. Ik heb er zelf voor gekozen. En daarmee ook voor hem.

Mijn zoon zal de organische herinneringen hebben van hier opgroeien, van het als je broekzak kennen van een buurt, maar niet de straatnamen weten. Omdat je die niet hoeft te kennen om je weg te vinden. Hij zal zwaar beladen raken van herinneringen aan Amsterdam. Elke voetstap een afdruk in zijn hart, die samen glinsterende paden vormen, als wortels in de klei van deze op palen gebouwde stad.

Dit is de speeltuin waar hij leerde lopen. Dit is de boom waar hij leerde klimmen. Dit is het park waar hij leerde fietsen. Op deze straathoek wachtte hij op zijn vrienden en in deze gracht zwom hij in de zomer als de hitte in ons pakhuis niet te doen was. Hier kuste hij voor het eerst een meisje, of een jongen, dat weet ik nu nog niet. En verderop het IJ, waar de wind zijn buien altijd kon kalmeren. Paden die uitwaaieren naar de voetbalvelden, de zwemplassen, de muziektempels van de stad, over grachten, straten en bruggen.

En hij zal niet anders weten.

De lijnen die uitliepen van mij in hem schieten nu wortel in deze straten. Vormen een glinsterend web, een vangnet voor altijd.

En hoezeer we ook ons leven hier nu delen, onze herinneringen zullen nooit dezelfde zijn. In dezelfde straten ziet hij andere dingen, dezelfde dingen ziet hij met andere ogen.

Allebei houden we van Amsterdam. De wind waait door de straten en door onze haren en we voelen ons thuis.

Mijn Amsterdam en zijn Amsterdam. Ons Amsterdam.

Biden Infrastructure Plan Is A Step Toward Equity And Countering Climate Crisis

President Joe Biden’s economic plan, which is aimed at overhauling U.S. infrastructure, helping workers and their families, and raising taxes for the ultrarich, surely represents a big step in the right direction for equality and sustainability. It’s also not the end-all, be-all for economic and environmental policy. Much more will be needed to work toward real equity and avert the worst impacts of the climate crisis.

In this exclusive interview for Truthout, one of the world’s leading progressive economists, Robert Pollin, distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, explains what Biden’s economic plan means for the majority of American people and how it will help create a somewhat fairer tax system.

C.J. Polychroniou: Biden’s tax plan is to raise taxes for high-income individuals and corporations in order to create a fairer taxation system. Yet, lots of people seem to be worried about it, including investors and small business. Can you explain Biden’s tax plan and whether the targets he has set for it will indeed produce a fairer tax system?

Robert Pollin: The Biden administration has proposed a series of tax measures that would raise rates on U.S. corporations and the wealthy. These proposals include the following:

– An increase in the corporate income tax rate from the current 21 percent rate to 28 percent;

– Establish a minimum tax rate of 21 percent on the foreign income of U.S. multinational corporations;

– Increase the top individual income tax rate for the richest 1 percent from 37 percent to 39.6 percent; and

– Increase the taxes that top 1 percent pay on their capital gains — i.e., the money they obtain from selling assets, like stocks, bonds and real estate — from the current 20 percent to 39.6 percent.

There are two interrelated purposes of these tax proposals. The first is to have big corporations and the rich contribute a larger share to the federal government’s overall tax revenues. The second is to generate significantly more tax revenue, in order to pay for Biden’s major investment proposals, the “American Jobs Plan” and “American Families Plan.” These Biden proposals include investments to: 1.) upgrade the country’s traditional infrastructure, such as roads, bridges and water management systems; 2.) make broadband access universal; 3.) dramatically improve the quality and accessibility of child care and elder care; and 4.) build a clean energy infrastructure capable of staving off the deepening global climate crisis. These programs are in addition to Biden’s “American Rescue Plan,” which became law in March. The American Rescue Plan is a short-term stimulus program to move the U.S. economy out of the COVID-induced recession onto a sustainable and equitable growth path. The Rescue Plan is financed mostly through government borrowing, while (in their current proposed versions at least) the Jobs and Families plans are financed through raising taxes.

It is not the least bit surprising that lots of people, including investors and businesses of all sizes, as well as high-end individual taxpayers, would be worried about Biden’s proposed tax increases to finance the Jobs and Families plans…. They are worried because they don’t want to pay higher taxes. But it will be useful to consider these worries in a broader context. Here are a few key points:

Even with Biden’s proposal is enacted in full (which is unlikely), the increase in the corporate income tax would still leave the corporations paying a lower tax rate than they paid between 1994 and 2017. The Biden proposal would simply bring rate back to the level it was before Trump and the congressional Republicans gifted corporations with a big tax cut. In addition, even with the 2017 official corporate tax rate at 21 percent, about 18 percent of the largest U.S. corporations managed to legally pay zero income taxes in 2018. They accomplished this, in part, through moving parts of their activities offshore, at least on paper. The Biden proposal would make the corporations pay taxes even when they move their activities offshore.

As is well-known, the United States has experienced an unprecedented rise in income inequality since the onset of the neoliberal era, starting roughly with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. Since 1980, the richest 1 percent of family share of the total family income for the whole country has gone from about 9 percent to over 20 percent — i.e. the share of overall income going to the richest 1 percent of families has more than doubled under neoliberalism. Even more striking has been the rewards for being in the richest 0.01 percent of families — among the richest 12,000 households in the U.S. in a society with about 120 million households today. The share of total family household income that the ultrarich has received has gone from less than 1 percent of the total just prior to the neoliberal era to over 5 percent today. Roughly speaking, in today’s dollars, that would mean that ultrarich household income would be about $10 million if they received 1 percent of the total versus getting $50 million today through their 5 percent share. Neoliberalism, in other words, has delivered a fivefold income increase for the society’s richest 12,000 families.

In short, the rich are going remain ridiculously rich and big corporations will continue receiving outsized profits in the U.S. even if Biden’s proposals were enacted in full and the tax system were consequently to become somewhat fairer. Moreover, the Biden tax increases would have limited to no impact on the take-home pay of either small business owners or the merely moderately affluent.

That said, there are still good reasons to fund at least a significant share of Biden’s American Jobs and American Families programs through the federal government borrowing money, as is being done with the Rescue Plan, as opposed to raising all the funds through taxing corporations and the wealthy. The first reason is that, as of this writing, the federal government can borrow money for 10 years while locking in the historically low interest rate of 1.6 percent. That means that, if the government were to borrow, say, $500 billion right now to support the Biden programs, it would have to pay $8 billion per year in interest to the people who bought the 10-year government bonds. Those interest payments would amount to less than three one-hundredths of 1 percent of 1 percent (0.03 percent) of annual U.S. GDP over that 10-year period.

1 June 2021 – International Farhud Day

Kunstmuseum Den Haag, Joseph Sassoon Semah, exhibition Over Vriendschap…. (29 August 2021) Architectoral model based on the mass grave of Jews in Baghdad – Farhud 1941

Sarah, was an 11-year-old nanny from Kurdistan living in Baghdad who witnessed the Farhud.

“ Eventually, the Farhud broke out, on the Eve of the Feast of Shavuot (Pentecost). They went out and started killing people. They would break into houses at night to rob and kill.

(…) In Baghdad, there were also Muslims who loved the Jews. Such Muslims would help their Jewish neighbour’s by writing on their neighbours’ doors ‘this house is Muslim’.

If a house had this sign, the rioters wouldn’t touch it. But if a house didn’t have such a sign, they would break in and kill those who were inside.” (Blog Dorota Molin, in Times of Israel, 5 May 2021)

De Autobandieten

Op 21 december 1911 vond in Parijs de eerste bankoverval in de geschiedenis plaats waarbij gebruik gemaakt werd van een auto. De daders waren vier mannen die deel uitmaakten van een groep anarchisten die door middel van overvallen de bourgeoisie in haar hart wilde treffen. In 1911 en 1912 zaaide de bende paniek in Parijs en omstreken met een serie spectaculaire en gewelddadige overvallen waarbij ze gebruik maakte van auto’s. In een tijd dat de ongewapende Franse politie zich nog per fiets verplaatste, was dat op z’n minst baanbrekend te noemen. De geschiedenis van deze Autobandieten, oftewel de Bende van Bonnot zoals de groep genoemd werd, is meerdere malen beschreven.[1] Hierin wordt echter weinig aandacht geschonken aan de autotypes die door deze Autobandieten voor hun acties werden gebruikt. Maar voor de leden van de groep was juist het weloverwogen uitzoeken van een bepaald automerk en type een essentieel onderdeel van hun wijze van opereren.

Overval

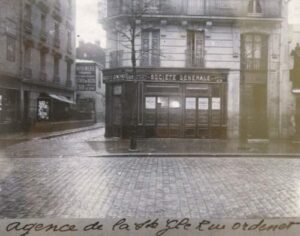

De Rue Ordener in Parijs is een brede, nogal saaie middenstandsstraat in het 18e Arrondissement, in het noorden van Montmartre. Op nummer 148, op de hoek van het zijstraatje Cité Nollez, is nu de kapsalon Air Coiffure gevestigd. In 1911 bevond zich hier een filiaal van de bank Société Générale. Op 21 december 1911 om 08.45 uur merkt een slager vanaf de overkant op dat een luxe auto met vier inzittenden, al geruime tijd met draaiende motor geparkeerd staat ter hoogte van nummer 142. Op het moment dat bij de bank geldloper Ernest Caby arriveert met zijn geldtas, zet de auto zich langzaam in beweging langs de stoeprand. Uit de auto springen twee mannen die de geldloper van dichtbij koelbloedig in de borst schieten, zijn tas grijpen en weer in de auto duiken. De chauffeur geeft gas, maakt met de auto een korte halve cirkel naar links en draait met piepende remmen de scherpe bocht met de Rue des Cloys in.[2] In volle vaart neemt hij vervolgens de eerste bocht naar rechts, de Rue Montcalm in, weet een bus en een taxi te ontwijken, en draait dan weer scherp naar rechts, de Rue Vauvenargues in. Vanuit de auto schieten de overvallers op enkele moedige omstanders die te voet de achtervolging hebben ingezet. Vijf minuten later snelt de auto Parijs uit door de Porte de Clichy.

Zelfs voor iemand zonder ervaring als automobilist, zoals schrijver dezes, is duidelijk dat voor het nemen van de bocht naar de Rue des Cloys, de nodige stuurmanskunst vereist moet zijn geweest. In ruim honderd jaar is aan de situatie ter plekke nauwelijks iets veranderd. Ook nu nog zou een automobilist bij het nemen van deze bocht beticht worden van onverantwoordelijk rijgedrag.

Illegalisme

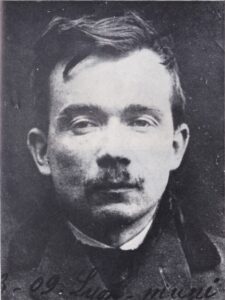

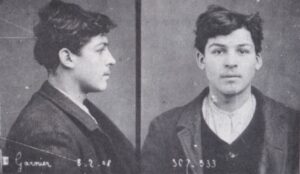

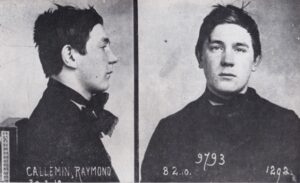

De chauffeur van de auto was Jules Bonnot, een uit Lyon afkomstige mecanicien en chauffeur, naar wie de groep daders later door pers en publiek werd vernoemd. Eigenlijk ten onrechte want Bonnot had zich pas kort voor de overval bij de groep aangesloten.[3] De groep had geen leider, hoewel de jonge activist Octave Garnier duidelijk overwicht had op de anderen. Garnier en de uit Brussel afkomstige Raymond Callemin losten de schoten op de geldloper. Wie de vierde man in de auto was, is altijd onduidelijk gebleven.

Garnier en Callemin, en ook medestander en latere medeovervaller André Soudy waren afkomstig uit kringen rond het tijdschrift l’anarchie en woonden in een anarchistische, veganistische leefgemeenschap in Romainville, een landelijk gelegen dorpje ten noordoosten van Parijs.[4] De uit zo’n zes kernleden en een twintigtal helpers bestaande groep meende dat de strijd tegen het kapitalistische systeem en tegen de uitbuiting van arbeiders, het beste gevoerd kon worden door het plegen van individuele en gemeenschappelijke, indien nodig gewelddadige, verzetsdaden tegen de heersende maatschappelijke orde. Dit illegalisme,

waarbij inbraken en overvallen gepleegd werden met als doel het ondermijnen van de maatschappelijke orde, zorgde ook voor financiële armslag voor de anarchistische beweging.

Directe, onverbloemde aanvallen op banken en vermogende burgers maakten deel uit van de werkwijze. In brede anarchistische kring werd dit anarchisme van de daad destijds veelal veroordeeld. De Autobandieten was een geïsoleerde groep outlaws die zichzelf bewust buiten de wet had geplaatst. Vanwege het feit dat hun acties niet alleen de bourgeoisie troffen, maar er ook onschuldige slachtoffers bij vielen, had de groep al gauw veel sympathie verloren.

Voor zowel de sensatiepers als de serieuze kranten was de groep maandenlang voorpaginanieuws.

Het gebruik van een auto moet de daders niet alleen de verzekering hebben gegeven dat zij na een actie snel konden vluchten, maar vooral moeilijk op te sporen waren. De mannen lieten de auto die avond achter op het strand in de buurt van Dieppe en namen de trein terug naar Parijs. Dat zij de allereerste bankoverval in de geschiedenis pleegden waarbij gebruik gemaakt werd van een auto, zal hen echter niet bezig hebben gehouden.[5]

Chique auto

Voor de overval was de keuze van Garnier en chauffeur/mecanicien Bonnot gevallen op een Delaunay-Belleville HB4, bouwjaar 1911. Garnier wilde de beste auto van dat moment hebben, het zou de aanval van de groep op het systeem immers nog meer onderstrepen, betoogde hij. Enig speurwerk leidde hen naar een exemplaar in Boulogne-sur-Seine – kenteken 783-X-3, motornummer 2679V, eigendom van M. Normand, 12 Rue de Chalet, Boulogne. Op 14 december 1911 werd de wagen door Bonnot, Garnier en Callemin uit de garage van de eigenaar ontvreemd.

Delaunay-Belleville was een kleine autofabriek in St. Denis bij Parijs en maakte auto’s met een chique, aristocratische uitstraling, die als exclusief voor de rijkere klasse te boek stonden.

Tsaar Nicolaas II, de Griekse koning George en koning Alphonso XIII van Spanje waren bezitters van een model uit 1906. Van het model HB4 werden in 1911 en 1912 slechts honderd vervaardigd. De carrosserie was uitgevoerd in zogenaamde Roi des Belges-stijl met een overdekte achterbank. De bestuurdersplaats was niet overdekt. Met de krachtige vier cilinder, 23 PK motor kon een topsnelheid van 70 km/u behaald worden. Voor de bestuurder was de auto soepel hanteerbaar. Kenners vergeleken de sierlijke beweegbaarheid en solide wegligging van de HB4 met die van een Rolls Royce Silver Ghost.

Dollemansrit

Twee maanden later, op 27 februari 1912, stalen Garnier, Bonnot en Callemin opnieuw een wagen van hetzelfde merk, nu een Labourdette Delaunay-Belleville Double Phaeton, bouwjaar 1908. Daarmee op weg naar een inbraak verloren ze echter veel tijd. Besloten werd halverwege om te keren en de auto door Parijs naar een voorlopige schuilplaats te loodsen. In de haast en wellicht enigszins overmoedig joeg Bonnot de auto op topsnelheid dwars door het centrum van Parijs. En passant reed hij een marktkraampje omver in de Rue de Rivoli, maar hij matigde zijn snelheid niet.

Voor het Gare St. Lazare kon hij net de bus van St. Germain naar Montmartre ontwijken.

Voetgangers zochten een goed heenkomen toen de auto het trottoir opschoot en tot stilstand kwam. Een verkeersagent die de onbesuisde automobilist wilde bekeuren sprong op de treeplank, juist toen Bonnot weer gas gaf. Voor het station, op de Place du Havre, werd de agent door Garnier met drie schoten uit een Browning van de treeplank afgeschoten. Hij overleed later in het ziekenhuis. Via de Rue Royale en de Place de la Concorde werd de dollemansrit vervolgd waarna de auto via de Porte Maillot de stad verliet. Twee dagen later werd de auto gebruikt bij een nachtelijke inbraak bij een gefortuneerde advocaat in Pontoise. Na gedane arbeid werd de wagen vervolgens in een achterafstraatje in St. Ouen door Garnier in brand gestoken.

Chomsky: Without US Aid, Israel Wouldn’t Be Killing Palestinians En Masse

Successive Israeli governments have been trying for years to push Palestinians out of the Holy City of Jerusalem, and the latest round of Israeli attacks fall in line with that goal. But to understand the roots of the current escalation — and the possible threat of all-out war — one must examine the U.S.-backed, foundational Israeli government policy of using strategies of “terror and expulsion” in an effort to expand its territory by killing and displacing Palestinians, says Noam Chomsky, in this exclusive interview for Truthout.

Successive Israeli governments have been trying for years to push Palestinians out of the Holy City of Jerusalem, and the latest round of Israeli attacks fall in line with that goal. But to understand the roots of the current escalation — and the possible threat of all-out war — one must examine the U.S.-backed, foundational Israeli government policy of using strategies of “terror and expulsion” in an effort to expand its territory by killing and displacing Palestinians, says Noam Chomsky, in this exclusive interview for Truthout.

Chomsky — a Laureate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Arizona and Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT — is internationally recognized as one of the most astute analysts of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and Middle East politics in general, and is a leading voice in the struggle to liberate Palestine. Among his many writings on the topic are The Fateful Alliance: The United States, Israel and Palestinians; Gaza in Crisis: Reflections on Israel’s War Against the Palestinians; and On Palestine.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, I want to start by asking you to put into context the Israeli attack against Palestinians at the al-Aqsa Mosque amid eviction protests, and then the latest air raid attacks in Gaza. What’s new, what’s old, and to what extent is this latest round of neo-colonial Israeli violence related to Trump’s move of the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem?

Noam Chomsky: There are always new twists, but in essentials it is an old story, tracing back a century, taking new forms after Israel’s 1967 conquests and the decision 50 years ago, by both major political groupings, to choose expansion over security and diplomatic settlement— anticipating (and receiving) crucial U.S. material and diplomatic support all the way.

For what became the dominant tendency in the Zionist movement, there has been a fixed long-term goal. Put crudely, the goal is to rid the country of Palestinians and replace them with Jewish settlers cast as the “rightful owners of the land” returning home after millennia of exile.

At the outset, the British, then in charge, generally regarded this project as just. Lord Balfour, author of the Declaration granting Jews a “national home” in Palestine, captured Western elite ethical judgment fairly well by declaring that “Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long tradition, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.”

The sentiments are not unfamiliar.

Zionist policies since have been opportunistic. When possible, the Israeli government — and indeed the entire Zionist movement — adopts strategies of terror and expulsion. When circumstances don’t allow that, it uses softer means. A century ago, the device was to quietly set up a watchtower and a fence, and soon it will turn into a settlement, facts on the ground. The counterpart today is the Israeli state expelling even more Palestinian families from the homes where they have been living for generations — with a gesture toward legality to salve the conscience of those derided in Israel as “beautiful souls.” Of course, the mostly absurd legalistic pretenses for expelling Palestinians (Ottoman land laws and the like) are 100 percent racist. There is no thought of granting Palestiniansrights to return to homes from which they’ve been expelled, even rightsto build on what’s left to them.

Israel’s 1967 conquests made it possible to extend similar measures to the conquered territories, in this case in gross violation of international law, as Israeli leaders were informed right away by their highest legal authorities. The new projects were facilitated by the radical change in U.S.-Israeli relations. Pre-1967 relations had been generally warm but ambiguous. After the war they reached unprecedented heights of support for a client state.

The Israeli victory was a great gift to the U.S. government. A proxy war had been underway between radical Islam (based in Saudi Arabia) and secular nationalism (Nasser’s Egypt). Like Britain before it, the U.S.tended to prefer radical Islam, which it considered less threatening to U.S. imperial domination. Israel smashed Arab secular nationalism.

Israel’s military prowess had already impressed the U.S. military command in 1948, and the ’67 victory made it very clear that a militarized Israeli state could be a solid base for U.S. power in the region— also providing important secondary services in support of U.S.imperial goals beyond. U.S. regional dominance came to rest on three pillars: Israel, Saudi Arabia, Iran (then under the Shah). Technically, they were all at war, but in reality the alliance was very close, particularly between Israel and the murderous Iranian tyranny.

Within that international framework, Israel was free to pursue the policies that persist today, always with massive U.S. support despite occasional clucks of discontent. The Israeli government’s immediatepolicy goal is to construct a “Greater Israel,” including a vastly expanded “Jerusalem” encompassing surrounding Arab villages; the Jordan valley, a large part of the West Bank with much of its arable land; and major towns deep inside the West Bank, along with Jews-only infrastructure projects integrating them into Israel. The project bypasses Palestinian population concentrations, like Nablus, so as to fend off what Israeli leaders describe as the dread “demographic problem”: too many non-Jews in the projected “democratic Jewish state” of “Greater Israel” — an oxymoron more difficult to mouth with each passing year. Palestinianswithin “Greater Israel” are confined to 165 enclaves, separated from their lands and olive groves by a hostile military, subjected to constant attack by violent Jewish gangs (“hilltop youths”) protected by the Israeli army.

Meanwhile Israel settled and annexed the Golan Heights in violation of UN Security Council orders (as it did in Jerusalem). The Gaza horror story is too complex to recount here. It is one of the worst of contemporary crimes, shrouded in a dense network of deceit and apologetics for atrocities.

Trump went beyond his predecessors in providing free rein for Israeli crimes. One major contribution was orchestrating the Abraham Accords, which formalized long-standing tacit agreements between Israel and several Arab dictatorships. That relieved limited Arab restraints on Israeli violence and expansion.

The Accords were a key component of the Trump geostrategic vision: to construct a reactionary alliance of brutal and repressive states, run from Washington, including [Jair] Bolsonaro’s Brazil, [Narendra] Modi’s India, [Viktor] Orbán’s Hungary, and eventually others like them. The Middle East-North Africa component is based on al-Sisi’s hideous Egyptian tyranny, and now under the Accords, also family dictatorships from Morocco to the UAE and Bahrain. Israel provides the military muscle, with the U.S. in the immediate background.

The Abraham Accords fulfill another Trump objective: bringing under Washington’s umbrella the major resource areas needed to accelerate the race toward environmental cataclysm, the cause to which Trump and associates dedicated themselves with impressive fervor. That includes Morocco, which has a near monopoly of the phosphates needed for the industrialized agriculture that is destroying soils and poisoning the atmosphere. To enhance the Moroccan near-monopoly, Trump officially recognized and affirmed Morocco’s brutal and illegal occupation of Western Sahara, which also has phosphate deposits.

It is of some interest that the formalization of the alliance of some of the world’s most violent, repressive and reactionary states has been greatly applauded across a broad spectrum of opinion.

So far, Biden has taken over these programs. He has rescinded the gratuitous brutality of Trumpism, such as withdrawing the fragile lifeline for Gaza because, as Trump explained, Palestinians had not been grateful enough for his demolition of their just aspirations. Otherwise the Trump-Kushner criminal edifice remains intact, though some specialists on the region think it might totter with repeated Israeli attacks on Palestinian worshippers in the al-Aqsa mosque and other exercises of Israel’s effective monopoly of violence.

Israel’s settlements have no legal validity, so why is the U.S. continuing to provide aid to Israel in violation of U.S. law, and why isn’t the progressive community focusing on this illegality?

Israel has been a highly valued client since the demonstration of its mastery of violence in 1967. Law is no impediment. U.S. governments have always had a cavalier attitude to U.S. law, adhering to standard imperial practice. Take what is arguably the major example: The U.S.Constitution declares that treaties entered into by the U.S. government are the “supreme law of the land.” The major postwar treaty is the UN Charter, which bars “the threat or use of force” in international affairs (with exceptions that are not relevant in real cases). Can you think of a president who hasn’t violated this provision of the supreme law of the land with abandon? For example, by proclaiming that all options are open if Iran disobeys U.S. orders — let alone such textbook examples of the “supreme international crime” (the Nuremberg judgment) as the invasion of Iraq.

The substantial Israeli nuclear arsenal should, under U.S. law, raise serious questions about the legality of military and economic aid to Israel. That difficulty is overcome by not recognizing its existence, an unconcealed farce, and a highly consequential one, as we’ve discussed elsewhere. U.S. military aid to Israel also violates the Leahy Law, which bans military aid to units engaged in systematic human rights violations.The Israeli armed forces provide many candidates.

Congresswoman Betty McCollum has taken the lead in pursuing this initiative. Carrying it further should be a prime commitment for those concerned with U.S. support for the terrible Israeli crimes against Palestinians. Even a threat to the huge flow of aid could have a dramatic impact.

Source: https://truthout.org/chomsky-without-us-aid

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, climate change, the political economy of the United States, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books, and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Arabic, Croatian, Dutch, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthout and collected by Haymarket Books; Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors); and The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthout and collected by Haymarket Books (scheduled for publication in June 2021)

Remaking The World Starts With The Green New Deal

While the Green New Deal will decarbonize the economy, it will also be egalitarian.

In an entry to his Prison Notebooks, in Notebook 3 of the year 1930, the Italian revolutionary Antonio Gramsci observed of the existing political conditions in his society that, “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

Today, it is the entire world that finds itself in the midst of such a tension. Capitalism’s addiction to the burning of fossil fuels is heating up the planet, subsequently creating conditions that pose a direct threat to humans and ecosystems. Actually, there are serious indications that we are on the edge of a complete climate breakdown. Even the Brazilian Amazon has turned now into a net emitter. Yet the future ways of powering the world economy are gestating—and it is still far from clear that global warming will be tamed.

However, this is not to suggest that there are no solutions to the climate emergency facing the planet Earth. In fact, we seem to have the ultimate solution to climate breakdown, but powerful interests do stand on the way and too many people appear to be rather scared of the proposed solution due to misconceptions fostered by those who wish to maintain the status quo for as long as possible, and “damn the consequences.”

Welcome to the Green New Deal!

The Green New Deal is a plan for tackling the climate emergency by doing away with fossil fuels and relying instead on clean, renewable and zero-carbon energy sources to power economies in the 21st century. The term itself emerged sometime during the 2007-08 financial crisis, and the first full proposal for a Green New Deal was put together by a UK-based Green New Deal group which drew its inspiration from the history of Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Still, while a range of studies on “green economy” were produced shortly thereafter and all throughout the 2010s, it is safe to say that the Green New Deal framework did not fire the public imagination until just a couple of years ago when Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and Senator Ed Markey (D-Mass) introduced a 14-page nonbinding resolution calling on the federal government to create a Green New Deal as a means of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and reshaping the US economy. Now the Green New Deal is a topic that’s on everyone’s lips. The idea has become the Left’s rallying cry and the Right’s worse nightmare.