Noam Chomsky: To Retain Power, Democrats Must Stop Abandoning The Working Class

The U.S. political system is broken, many mainstream pundits declare. Their claim rests on the idea that Republicans and Democrats are more divided than ever and seem to be driven by different conceptions not only of government, but of reality itself. However, the problem with the U.S. political system is more profound than the fact that Democrats and Republicans operate in parallel universes. The issue is that the U.S. appears to function like a democracy, but, essentially, it constitutes a plutocracy, with both parties primarily looking after the same economic interests.

In this interview, Noam Chomsky, an esteemed public intellectual and one of the world’s most cited scholars in modern history, discusses the current shape of the Democratic Party and the challenges facing the progressive left in a country governed by a plutocracy.

C.J. Polychroniou: In our last interview, you analyzed the political identity of today’s Republican Party and dissected its strategy for returning to power. Here, I am interested in your thoughts on the current shape of the Democratic Party and, more specifically, on whether it is in the midst of loosening its embrace of neoliberalism to such an extent that an ideological metamorphosis may in fact be underway?

Noam Chomsky: The short answer is: Maybe. There is much uncertainty.

With all of the major differences, the current situation is somewhat reminiscent of the early 1930s, which I’m old enough to remember, if hazily. We may recall Antonio Gramsci’s famous observation from Mussolini’s prison in 1930, applicable to the state of the world at the time, whatever exactly he may have had in mind: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

Today, the foundations of the neoliberal doctrines that have had such a brutal effect on the population and the society are tottering, and might collapse. And there is no shortage of morbid symptoms.

In the years that followed Gramsci’s comment, two paths emerged to deal with the deep crisis of the 1930s: social democracy, pioneered by the New Deal in the U.S., and fascism. We have not reached that state, but symptoms of both paths are apparent, in no small measure on party lines.

To assess the current state of the political system, it is useful to go back a little. In the 1970s, the highly class-conscious business community sharply escalated its efforts to dismantle New Deal social democracy and the “regimented capitalism” that prevailed through the postwar period — the fastest growth period of American state capitalism, egalitarian, with financial institutions under control so there were none of the crises that punctuate the neoliberal years and no “bailout economy” of the kind that has prevailed through these years, as Robert Pollin and Gerald Epstein very effectively review.

The business attack begins in the late 1930s with experiments in what later became a major industry of “scientific methods of strike-breaking.” It was on hold during the war and took off immediately afterwards, but it was relatively limited until the 1970s. The political parties pretty much followed suit; more accurately perhaps, the two factions of the business party that share government in the U.S. one-party state.

By the ‘70s, beginning with Nixon’s overtly racist “Southern strategy,” the Republicans began their journey off the political spectrum, culminating (so far) in the McConnell-Trump era of contempt for democracy as an impediment to holding uncontested power. Meanwhile, the Democrats abandoned the working class, handing working people over to their class enemy. The Democrats transitioned to a party of affluent professionals and Wall Street, becoming “cool” under Obama in a kind of replay of the infatuation of liberal intellectuals with the Camelot image contrived in the Kennedy years.

The last gasp of real Democratic concern for working people was the 1978 Humphrey-Hawkins full employment act. President Carter, who seemed to have had little interest in workers’ rights and needs, didn’t veto the bill, but watered it down so that it had no teeth. In the same year, UAW president Doug Fraser withdrew from Carter’s Labor-Management committee, condemning business leaders — belatedly — for having “chosen to wage a one-sided class war … against working people, the unemployed, the poor, the minorities, the very young and the very old, and even many in the middle class of our society.”

The one-sided class war took off in force under Ronald Reagan. Like his accomplice Margaret Thatcher in England, Reagan understood that the first step should be to eliminate the enemy’s means of defense by harsh attack on unions, opening the door for the corporate world to follow, with the Democrats largely indifferent or participating in their own ways — matters we’ve discussed before.

The tragi-comic effects are being played out in Washington right now. Biden attempted to pass badly needed support for working people who have suffered a terrible blow during the pandemic (while billionaires profited handsomely and the stock market boomed). He ran into a solid wall of implacable Republican opposition. A major issue was how to pay for it. Republicans indicated some willingness to agree to the relief efforts if the costs were borne by unemployed workers by reducing the pittance of compensation. But they imposed an unbreachable Red Line: not a penny from the very rich.

Nothing can touch Trump’s major legislative achievement, the 2017 tax scam that enriches the super-rich and corporate sector at the expense of everyone else — the bill that Joseph Stiglitz termed the U.S. Donor Relief Act of 2017, which “embodies all that is wrong with the Republican Party, and to some extent, the debased state of American democracy.”

Meanwhile, Republicans claim to be the party of the working class, thanks to their advocacy of lots of guns for everyone, Christian nationalism and white supremacy — our “traditional way of life.”

To Biden’s credit, he has made moves to reverse the abandonment of working people by his party, but in the “debased state” of what remains of American democracy, it’s a tough call.

Humanity Needs To Declare Independence From Fossil Fuels

The Declaration of Independence, the work of a five-person committee appointed by the Continental Congress, but with Thomas Jefferson as the most vocal figure of the values of the Enlightenment on this side of this Atlantic being the primary author and upon the insistence of none other than John Adams himself, is one of the most important documents in the history of democracy and of political progress.

Built around Locke’s political epistemology, the Declaration of Independence signaled to the world that the old political order based on the divine right of kings and political absolutism in general was illegitimate and that, subsequently, people have the right to overthrow a regime that fails to protect the “self-evident” rights of every individual, which are “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

The Declaration of Independence, the official birth certificate of the American nation and the most progressive document of its time in support of popular sovereignty, was officially approved by the Congress on July 4, 1776, but eventually it would end up becoming an inspiration to future generations both in the United States and around the world. For example, the “Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions” issued by early feminists at the July 1848 Seneca Falls Convention was modelled after the Declaration of Independence. Ho Chi Ming’s speech on September 2, 1945, proclaiming the Independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam, began with nearly an exact quote from the second paragraph of America’s 1776 Declaration of Independence.

Today, the United States and the world at large need a new declaration of independence—a declaration of independence from fossil fuels.

The planet is on the verge of unmitigated disaster due to global warming. The Industrial Revolution, which began in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, brought about a series of major transformations in energy usage– first from wood to coal and then to oil and gas. And, to be sure, for more than a century, from the 1870s to the 1970s, to be exact, the world experienced unprecedented economic growth, although the relationship between economic growth and fossil fuel energy consumption is not straightforwardly linear for both developed and emerging economies.

However, for several decades now, we have also known of the effects of fossil fuels on the environment and climate change. The burning of fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gasses trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere, causing global warming. The Earth’s average global temperature has risen by 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit, according to NASA’s Godard Institute. Some regions of the world, however, have already seen average temperatures rise by more than 2 degrees Fahrenheit because temperatures increase at different speeds, with land areas warming faster than coastal areas.

Global temperatures matter. Rising global temperatures have major effects on numerous fronts, ranging from air quality and rising sea levels to the frequency of environmental events such as forest fires, hurricanes, heat waves, floods, droughts, and so on. The climate crisis also impacts on human rights and becomes a driver of migration. And last but not least, there are economic costs associated with the climate crisis as rising temperatures affect a wide range of industries, from agriculture to tourism. It’s estimated that the economic damage caused by natural disasters for the most recent decade (2000-2009) was approximately $3 trillion–more than $1 trillion increase from the previous decade.

Make no mistake about it. The world’s most authoritative voice on the climate crisis, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ICPP), has been warning us for several years now that the world is at serious risk, and that time is running out to save the planet. Yet, very little has been done so far to address our climate crisise, although we know what needs to be done.

What needs to be done is to move the world economy to net-zero emissions and 100 clean energy. This requires, starting immediately, to implement a radical plan for the phasing out of fossil fuels and the concomitant implementation of a green global infrastructure development plan. In this massive undertaking, the public sector needs to become the vanguard of the transition to clean and renewable energy, with the citizenry fully on its corner and against those greedy capitalists who continue to put profits ahead of people and the planet’s future.

We have the technical know-how as well as the available economic resources to make the transition to a clean energy future. Details of this undertaking are spelled out, for instance, in the recent publication of Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (Verso 2020) by Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin.

Moreover, the transition to a clean energy future does not mean the end of economic growth. On the contrary, a Global Green New Deal, as University of Massachusetts-Amherst economics professor Robert Pollin has sketched out in the aforementioned book, will generate millions of new and good-paying jobs in both the developed and the developing countries. The economic benefits of a green new deal are quite significant, while the costs of not doing a green new deal are catastrophic.

In sum, the time has come for the people of the United States—and indeed of citizens all over the beautiful blue planet—to announce a new Declaration of Independence: a declaration of independence from fossil fuels. This is our only chance to move towards a sustainable future, our only chance to avoid the highly likely probability of a return to barbarism due to the collapse of organized social order brought about by mitigating global warming.

Degrowth Policies Cannot Avert Climate Crisis. We Need A Green New Deal

The Green New Deal is the boldest and most likely the most effective way to combat the climate emergency. According to its advocates, the Green New Deal will save the planet while boosting economic growth and generating in the process millions of new and well-paying jobs. However, a growing number of ecological economists contend that rescuing the environment necessitates “degrowth.”

To the extent that a sharp reduction in economic activity is a positive goal, “degrowth” requires overturning the current world order. But do we have the luxury to wait for a new world order while the catastrophic impacts of global warming are already upon us and getting worse with each passing decade?

World-renowned progressive economist Robert Pollin, distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, is one of the leading proponents of a global Green New Deal. In this interview, he addresses the degrowth vs. Green New Deal debate, looking at how economies can grow while still advancing a viable climate stabilization project as long as the growth process is absolutely decoupled from fossil fuel consumption.

C.J. Polychroniou: Since the idea of a Green New Deal entered into public consciousness, the debate about climate emergency is becoming increasingly polarized between those advocating “green growth” and those arguing in support of “degrowth.” What exactly does “degrowth” mean, and is this at the end of the day an economic or an ideological debate?

Robert Pollin: Let me first say that I don’t think that the debate on the climate emergency between advocates of degrowth versus the Green New Deal is becoming increasingly polarized, certainly not as a broad generalization. Rather, as an advocate of the Green New Deal and critic of degrowth, I would still say that there are large areas of agreement along with some significant differences. For example, I agree that uncontrolled economic growth produces serious environmental damage along with increases in the supply of goods and services that households, businesses and governments consume. I also agree that a significant share of what is produced and consumed in the current global capitalist economy is wasteful, especially much, if not most, of what high-income people throughout the world consume. It is also obvious that growth per se as an economic category makes no reference to the distribution of the costs and benefits of an expanding economy. I think it is good to keep in mind both the areas of agreement as well as the differences.

But what about definitions: What do we actually mean by the Green New Deal and degrowth?

Starting with the Green New Deal: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that for the global economy to move onto a viable climate stabilization path, global emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) will have to fall by about 45 percent as of 2030 and reach net zero emissions by 2050. As such, by my definition, the core of the global Green New Deal is to advance a global project to hit these IPCC targets, and to accomplish this in a way that also expands decent job opportunities and raises mass living standards for working people and the poor throughout the world. The single most important project within the Green New Deal entails phasing out the consumption of oil, coal and natural gas to produce energy, since burning fossil fuels is responsible for about 70 – 75 percent of all global CO2 emissions. We then have to build an entirely new global energy infrastructure, the centerpieces of which are high efficiency and clean renewable energy sources — primarily solar and wind power. The investments required to dramatically increase energy efficiency standards and to equally dramatically expand the global supply of clean energy sources will also be a huge source of new job creation, in all regions of the world. These are the basics of the Green New Deal as I see it. It is that simple in concept, while also providing specific pathways for achieving its overarching goals.

Now on degrowth: Since I am not a supporter, it would be unfair for me to be the one explaining what it means. So here is how some of the leading degrowth proponents themselves describe the concept and movement. For example, in a 2015 edited volume titled, Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era, the volume’s editors Giacomo D’Alisa, Federico Demaria and Giorgos Kallis write that, “The foundational theses of degrowth are that growth is uneconomic and unjust, that it is ecologically unsustainable and that it will never be enough.” More recently, a 2021 paper by Riccardo Mastini, Giorgos Kallis and Jason Hickel, titled, “A Green New Deal without Growth?,” write that “ecological economists have defined degrowth as an equitable downscaling of throughput, with a concomitant securing of wellbeing.”

It is instructive here that, in this 2021 paper, Mastini, Kallis and Hickel do also acknowledge that degrowth has not advanced into developing a specific set of economic programs, writing that “degrowth is not a political platform, but rather an ‘umbrella concept’ that brings together a wide variety of ideas and social struggles.” This acknowledgement reflects, in my view, a major ongoing weakness with the degrowth literature, which is that, in concerning itself primarily with very broad themes, it actually gives almost no detailed attention to developing an effective climate stabilization project, or any other specific ecological project. Indeed, this deficiency was reflected in a 2017 interview with the leading ecological economist Herman Daly himself, without question a major intellectual progenitor of the degrowth movement. Daly says in the interview that he is “favorably inclined” toward degrowth, but nevertheless demurs that he is “still waiting for them to get beyond the slogan and develop something a little more concrete.”

The IHRA’s Careless Conflations On Antisemitism (And Few Alternatives)

Contending Modernities, 2021. In this essay Moshe Behar critiques the recent letter sent by English Secretary of State Gavin Williamson to university chancellors instructing them to adopt the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliances’ (IHRA) definition of antisemitism.

Behar contends that the definition of antisemitism that the IHRA has put forward is meant to squash legitimate democratic forms of criticism of the state of Israel much more than to help identify and stamp out antisemitism.

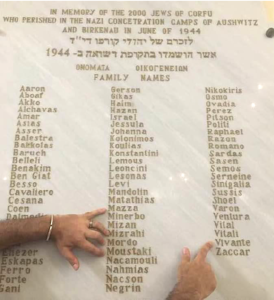

I am a non-white Mizrahi Jewish academic who has been studying Israel/Palestine and the history of Jews in the Middle East for two decades. My family hails from Ottoman Palestine, Egypt, Tunisia, and the Greek islands of Zakynthos and Corfu. All too many of us were murdered by Nazi Génocidaires (and rest assured that we will not forget or forgive).

Precisely because of this scholarly and biographic background I was embarrassed to read the letter sent by England’s Secretary of State for Education, Gavin Williamson, to all university vice chancellors. Utilizing an authoritarian tone devoid of understatement, Williamson demanded that all universities in England adopt formally what is called “the working definition of antisemitism” drafted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA).

Photo from the Synagogue in Kerkyra/Corfu. Fingers pointing out to families associated with Behar’s maternal lineage, Mother’s maiden name included.

Born in 1976, Williamson has been a Tory politician for 25 years. He and his party have not been noteworthy for their passionate activism against racism, antisemitism included. Nor did Williamson find it problematic to serve under Boris Johnson, author of Seventy-Two Virgins (HarperCollins, 2004), a novel that disappointingly recycled antisemitic tropes and stereotypical portrayals of Jews and other British minority ethnic groups.

The letter Williamson authored is littered with antisemitic tropes. A non-Jew himself, Williamson first chooses to single out Jews from non-Jews and, in so doing, officially mark Jews as “other.” Embracing the “divide and conquer” colonial approach, he proceeds to divorce antisemitic racism from similar manifestations of racism with which he is less concerned, including Islamophobia, Afrophobia/anti-Black racism, misogyny, anti Roma/Gypsy racism, homophobia, and xenophobia vis-à-vis Asians and Arabs.

Most disturbingly, Williamson’s letter upgrades the quintessential stereotype of money and Jews to a new level by linking Jews to monetary penalties and potential state sanctions on universities if their managements exercise what is otherwise a simple academic and democratic right to adopt a view and definition of antisemitism that differ from his. The irony of setting Christmas as the deadline for his pseudo-philosemitic mobilization has apparently escaped Williamson altogether.

The IHRA definition that Williamson labors to impose unilaterally defines antisemitism as “a perception that may be expressed as hatred.” This reading is vague, restrictive, minimalist, and in the main emotionalist. It bypasses manifestations of antisemitism that are equally, and possibly even more, important than “perception,” including oppression, discrimination, exclusion, prejudice, bigotry or other tangible actions. Moreover, a wall-to-wall agreement prevails among the rainbow of scholars of antisemitism that one singular definition of the abhorrent phenomenon does not exist. That is the case precisely as there is no one and only definition for racism, feminism, islamophobia, Judaism, Zionism, Islamism, English nationalism, communitarianism, and forms of bigotry.

There are at least four additional definitions of antisemitism that can guide the work of scholars or activists and that are analytically superior to that of the IHRA: the definition of the Canadian Independent Jewish Voices; that of the British Board of Deputies and the Community Security Trust; and that of the British Jewish Voice for Labour. However, the most scholarly rigorous definition is “The Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism” (JDA) that was made public today (disclosure: some serious reservations notwithstanding, I’m one of its 200 academic signatories). To be sure, Williamson’s top-down state decree of a single definition upon academia let alone one deemed deficient by hundreds of scholars runs the risk of echoing Soviet Stalinism and American McCarthyism.

And Then There Is Israel

As many as seven of the eleven illustrations that the IHRA definition marshals to exemplify antisemitism relate to post-1948 Israel (of which I happen to be a citizen). The Zionist/Arab matrix dominates the definition and as a result it often comes across as concerned more with the protection of Israel than the protection of Jews, let alone non-Israeli Jews. As early as 2016 the British Government’s own “Home Affairs Committee” found the IHRA’s definition wanting; cross-party committee members insisted on formally affixing two stipulations: (1) “It is not anti-Semitic to criticise the Government of Israel, without additional evidence to suggest anti-Semitic intent” and (2) “It is not anti-Semitic to hold the Israeli Government to the same standards as other liberal democracies, or to take a particular interest in the Israeli Government’s policies or actions, without additional evidence to suggest anti-Semitic intent ” (italics added).

While it is unclear how precisely such “intent” is to be established or proven let alone by what body or individual/s it is clear that Williamson opted consciously to exclude these two surgical qualifications. That seems an additional testament to his instrumentalization of antisemitism for sectarian conservative ends. The Governing Bodies and Presidents/Vice Chancellors of at least 48 universities were unable to withstand the ongoing governmental pressure and effectively all endorsed the IHRA definition top-down without staff consultation. For example, my university’s management endorsed the definition with the Home Affairs Committee’s stipulations; Cambridge and Oxford did the same. While this too remains unsatisfactory, it is somewhat less misguided than adopting the IHRA definition as is.

The definition Williamson insists on imposing carelessly conflates “Jews” with “the state of Israel” and “Judaism” with “modern political Zionism.” The original conflation between these identities and phenomena was and remains an inherent organizing pillar of Zionist ideology. Self-proclaimed pro-Israel bodies and individuals exercise this conflation regularly in texts, actions, and advocacy. It comes as no surprise that this conflation has often been reproduced by Israel’s anti-Zionist critics, at times consciously and at other times as a consequence of inexcusable ignorance.

Recent example of irresponsible conflation between British Jews, Zionism, and Israel’s belligerent occupation.

The symbiosis between these opposing, yet mutually-empowering, Zionist/anti-Zionist tides yields the most toxic ground for unambiguous manifestations of antisemitism. This is in contrast to cases where straightforward criticisms of Israel including by such organizations as Amnesty International, Oxfam, Human Rights Watch, and the Open Society Institute (established in 1993 by George Soros) have been fancifully labelled as “antisemitic” to delegitimize pro-democratic activism on behalf of Palestinian human and political rights. Three facts that the IHRA definition fails to acknowledge should neither be forgotten nor blurred conceptually: that many Jews are not Zionist; that the majority of Zionists worldwide are not Jewish (including Christian fundamentalists); and that over 20% of Israeli citizens are not Jewish.

- Page 3 of 3

- previous page

- 1

- 2

- 3